Abstract

Objective

Homicide and suicide are two important and potentially preventable causes of maternal injury. We analyzed data from the National Violent Death Reporting System to estimate the rates of pregnancy-associated homicide and suicide in a multi-state sample, to compare these rates with other causes of maternal mortality, and to describe victims’ demographic characteristics.

Methods

We analyzed data from female victims of reproductive age from 2003–2007. We identified pregnancy-associated violent deaths as deaths due to homicide or suicide during pregnancy or within the first year postpartum. We calculated the rates of pregnancy-associated homicide and suicide as the number of deaths per 100,000 live births in the sample population. We used descriptive statistics to report victims’ demographic characteristics and prevalence of intimate partner violence (IPV).

Results

There were 94 counts of pregnancy-associated suicide and 139 counts of pregnancy-associated homicide, yielding pregnancy-associated suicide and homicide rates of 2.0 and 2.9 deaths/100,000 live births, respectively. Victims of pregnancy-associated suicide were significantly more likely to be older and of Caucasian or American Indian descent as compared to all live births in NVDRS states. Pregnancy-associated homicide victims were significantly more likely to be at the extremes of the age range and African American. 54.3% of pregnancy-associated suicides involved intimate partner conflict that appeared to contribute to the suicide. 45.3% of pregnancy-associated homicides were IPV-associated.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that pregnancy-associated homicide and suicide are important contributors to maternal mortality and confirm the need to evaluate the relationships between socio demographic disparities and IPV with pregnancy-associated violent death.

Introduction

While deaths due to obstetrically-related events, such as cardiac disease, infection, and hemorrhage, have improved, maternal mortality due to injury has remained constant.(1) In fact, several studies have demonstrated that maternal injury is a leading cause of maternal mortality.(2–9) Homicide and suicide are two important and potentially preventable causes of maternal injury. However, the study of homicide and suicide has been limited by (1) a lack of information concerning victim-to-suspect relationships; (2) studies limited to localized samples, such as single state or city data, or data restricted to either urban or rural locations; (3) little information regarding precipitating circumstances to these deaths; and (4) likely underreporting of maternal violent deaths, especially due to reliance on death certificates alone (which may vary by state and contain missing information in the cause-of-death section)(10).

We sought to address these gaps in the literature by conducting a secondary data analysis of maternal violent death from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS), a multi-state database which collects data on violent deaths, including victim-to-suspect relationships, using multiple, complementary data sources, including police reports, death certificates, and coroner/medical examiner reports. This study aims to:

estimate the rates of pregnancy-associated (occurring during pregnancy or the first year postpartum) homicide and suicide in a multi-state sample;

compare these rates with other causes of mortality during the perinatal period;

describe the demographic characteristics of victims of pregnancy-associated violent death; and

estimate the prevalence of intimate partner conflict associated with these maternal deaths.

As many as 16–23% of American women experience intimate partner violence (IPV) during their pregnancy(11). As previous data has suggested a strong association between intimate partner violence (IPV) and pregnancy-associated homicide, a significant association between IPV and suicidality and suicides in women(12–16), and a potential relationship between IPV and pregnancy-associated suicide(17), we hypothesized that intimate partner conflict may be related to pregnancy-associated violent death in this multi-state sample. This relationship requires the understanding of victim-to-suspect relationships and precipitating circumstances, both variables that are available in the NVDRS.

Materials and Methods

The NVDRS

We conducted a secondary data analysis of the NVDRS, a multi-state active surveillance system run by the CDC. The NVDRS began collecting violent death data in 2003. Participating states collect risk factor data on all violent deaths, including homicides, suicides, unintentional deaths by firearms, legal intervention deaths, and deaths of undetermined intent. Seven states participated in 2003 and 13 in 2004. In 2005, the number of participating states increased to 17, including South Carolina, Georgia, North Carolina, Virginia, New Jersey, Maryland, Alaska, Massachusetts, Oregon, Colorado, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, Wisconsin, California, Kentucky, New Mexico, and Utah. All states report state-wide data except California, which gathers information only in a limited number of counties.(18)

The NVDRS is incident-based (not victim-based), meaning that it contains reports related to both victims and suspects associated with a given incident within one incident record. This links all victims and suspects with a given incident, permitting researchers to determine if the suspect was a partner of the victim. The system also uses multiple complementary data sources, including not only death certificates but also coroner/medical examiner records(CME)and police reports and contains about 250 unique data elements, including data on victim characteristics and precipitating circumstances of death.(18) Each state health department’s NVDRS office coordinates the abstraction process which may include electronic transfer of data from primary sources and/or manual abstraction from the records maintained by primary sources at their offices [ref coding manual]. A coding manual is provided, and coding training is held annually for all participating states [ref MMWR SS-3]. In addition, the CDC provides ongoing coding support through conference calls and an email helpdesk [same ref]. NVDRS states use multiple abstractors to perform blinded reabstraction of cases for reliability checks. The CDC also conducts a quality of control analysis, with a particular focus on abstractor-assigned variables. Further detail related to the NVDRS coding procedures is available at http://www.cdc.gov/ncipc/profiles/nvdrs.

Pregnancy/Postpartum Status

The NVDRS collects information regarding pregnancy or postpartum status at the time of death. Information regarding pregnancy status is abstracted from the CME and the death certificate. The coding structure of the NVDRS pregnancy status variable was designed to match the U.S. standard death certificate, which was modified in 2003 to include checkboxes to differentiate whether a woman was pregnant, within 42 days postpartum, within one year postpartum, or not pregnant within the last year at the time of death.(10) By 2005, only 5 of the participating NVDRS states were using this version of the U.S. standard death certificate.(19) Therefore, two additional responses are available on the coding tree for states with death certificates that do not include a timeline that matches the U.S. standard death certificate: “Not pregnant, not otherwise specified” and “Pregnant, not otherwise specified.” (18) For the purposes of our analysis, we treated values “Pregnant at the time of death” and “Pregnant, not otherwise specified” as pregnant at the time of death and values “Not pregnant but pregnant within 42 days of death” and “Not pregnant but pregnant 43 days to 1 year before death” as pregnant within one year of death.

Study Definition of Maternal Violent Death

The CDC-American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Maternal Mortality Study Group defined the term pregnancy-associated mortality to include “any death of a woman while pregnant or within one year of the termination of pregnancy, regardless of cause”; this includes deaths related and unrelated to pregnancy. (4) In keeping with this terminology, we used the terms pregnancy-associated homicide and pregnancy-associated suicide to represent deaths during pregnancy or within one year postpartum due to homicide and suicide, respectively. In addition, we used the terms pregnancy-associated homicide rate and pregnancy-associated suicide rate to refer to the number of pregnancy-associated homicides and suicides per 100,000 live births, respectively. We used the term pregnancy-associated violent death to refer to deaths from homicide and suicide combined. The term “pregnancy-associated” refers to the timing of the death and does not mean that the homicide or suicide was caused by pregnancy or postpartum status.

NVDRS Variables Related to Intimate Partner Violence

The NVDRS contains six variables related to intimate partner violence: “victim-to-suspect relationship”; “intimate partner problem” (suicides only); “perpetrator of interpersonal violence” (suicides only); “victim of interpersonal violence” (suicides only);” intimate partner violence-related” (homicides only); or “jealousy (lover’s triangle” (homicides only):(18)

“Victim-to-suspect relationship”: The victim-to-suspect relationship is abstracted based on the police report and the CME. Abstractors report the relationship as one of 29 relationship types or as “unknown.” For the purpose of our study, we defined a relationship as an intimate partner relationship if it was coded as any one of the following 5 relationship categories: “Spouse”; “Ex-spouse”; “Girlfriend or boyfriend”; “Ex-girlfriend or ex-boyfriend”; or “Girlfriend or boyfriend, unspecified whether current or ex.” (18)

“Intimate partner problem” (suicides only) and “Perpetrator of interpersonal violence” (suicides only): For suicide victims, NVDRS abstractors record whether “problems with a current or former intimate partner appear to have contributed to the suicide.” The abstractors are instructed to code this variable as “Yes” if, after reviewing the CME, police report, and child fatality report, if applicable, they found that “at the time of the incident the victim was experiencing problems with a current or former intimate partner, such as a divorce, break-up, argument, jealousy, conflict, or discord.” In the case of suicides, abstractors also code whether the victim was a known perpetrator or victim of interpersonal violence during the month prior to death. Interpersonal problems include, but are not limited to, intimate partner violence.(18)

“Intimate partner violence-related” (homicides only) and “Jealousy (lover’s triangle)” (homicides only): For homicide victims, NVDRS abstractors record “cases in which a homicide is related to conflict between current or former intimate partners.” Abstractors are instructed to code this variable as “Yes,” if after reviewing the CME, police report, and child fatality report, if applicable, they find that the death is perpetrated by an intimate partner or is associated with intimate partner violence or conflict. The CDC defines an intimate partner as a “current or former girlfriend/boyfriend, date, or spouse” in relation to this variable. In addition, abstractors code whether “jealousy or distress over an intimate partner’s relationship or suspected relationship with another personal lead to the homicide” (coded as “jealousy (lover’s triangle)).(18)

Sample

For the purpose of this study, we limited our analysis to women of reproductive age (15–54) from the 16 states reporting complete data to the NVDRS. The CDC National Vital Statistics System reports birth and maternal mortality information for women in the category of “under 15”. However, we excluded women less than 15 due to the extremely small sample size; the NVDRS prohibits reporting of a) cells showing or derived from fewer than five deaths (zero cells may be shown) and b) rates computed from cells containing less than 20 deaths or cases. Data was analyzed for the years 2003–2007 as this was the most current sample available for the NVDRS.

Analysis

The primary focus of this analysis was to estimate the overall rate of pregnancy-associated homicide and suicide, describe the demographic characteristics of the victims associated with these deaths, and estimate the prevalence of intimate partner conflict related to these deaths. We calculated the rates of pregnancy-associated homicide and suicide by dividing the total number of pregnancy-associated homicides and suicides, respectively, by the number of live births in the sample population, using data from the national natality files of the CDC.(20) We converted the results to maternal mortality rates by reporting the number of deaths per 100,000 live births. We used descriptive statistics to report demographic characteristics of victims and the prevalence of intimate partner conflict associated with the pregnancy-associated violent deaths in our sample. We were unable to analyze data for the “perpetrator of interpersonal violence” (suicides only), “victim of interpersonal violence” (suicides only), and “jealousy” (homicides only) due to a high data coded as “no/not available/unknown” together for these variables, leaving us unable to differentiate missing data from data coded as “no”.

We used two-sample tests of proportions to compare socio-demographic variables among victims of pregnancy-associate homicide and pregnancy-associated suicide with women with live births within the NVDRS states during the same time period, using data from the national natality files of the CDC.(20)We also used a two-sample test of proportions to compare the pregnancy-associated homicide and suicide rates, respectively, in the NVDRS using the U.S. standard death certificate versus those that did not. A p-value of <.05 was considered statistically significant. This study was deemed IRB-exempt by the University of Michigan IRBMED.

Results

Pregnancy-associated Violent Deaths

In total, we identified 233 pregnancy-associated violent deaths, yielding an overall pregnancy-associated violent death mortality rate of 4.9 per 100,000 live births. 64.8% of the pregnancy-associated violent deaths in our sample (n=151) occurred during pregnancy (vs. the first year postpartum).

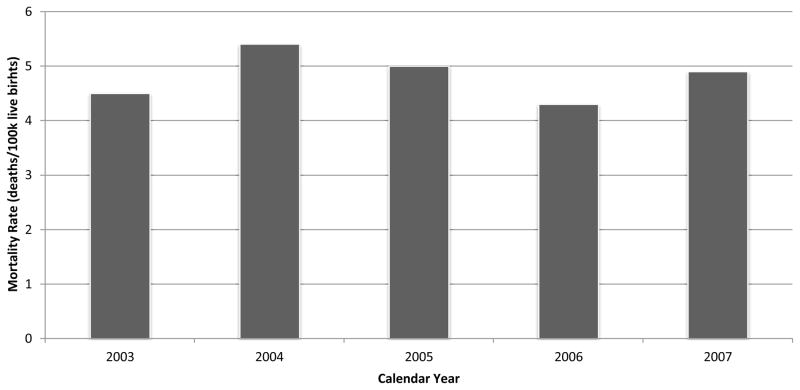

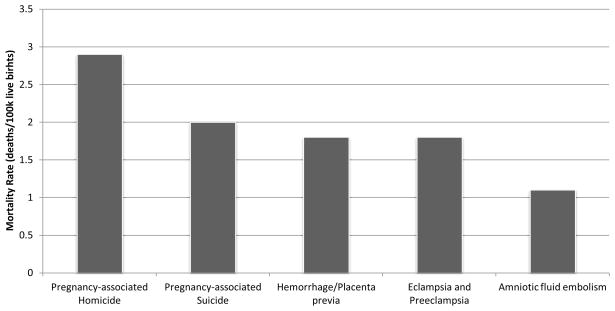

The overall pregnancy-associated violent death rate was fairly stable over the study time period, ranging from 4.3 to 5.4 (Figure 1). In addition, the rates of pregnancy-associated homicide and suicide were each higher than the mortality rates due to common obstetric causes (Figure 2).38

Figure 1. Pregnancy-Associated Violent Death Rate.

Pregnancy-Associated Violent Death Rate in our sample over the years 2003–2007.

Figure 2. Maternal Mortality: Violent Death vs. Specific Obstetric Causes.

*data from 2003–2007 NVDRS (pregnancy-associated homicide and suicide; this analysis) and Berg et al. 201038 (pregnancy-related mortality due to hemorrhage; hypertensive disorders; amniotic fluid embolism); deaths from specific obstetric causes are calculated as deaths during pregnancy or within the first year postpartum

Pregnancy-associated Suicide

There were 94 counts of pregnancy-associated suicide in our sample, yielding a pregnancy-associated suicide rate of 2.0 per 100,000 live births (Figure 3). 43 of the pregnancy-associated suicides occurred during pregnancy (45.7%), and 51 occurred postpartum. Older mothers were at greatest risk of pregnancy-associated suicide. Women 40 and above represented 17.0% of pregnancy-associated suicides but account for just 2.8% of live births in the NVDRS states(p<.01). In addition, victims of suicide were significantly more likely to be White and of American Indian descent and more often unmarried, as compared to women with all live births in the NVDRS states. The rate of pregnancy-associated suicide did not differ significantly between states that did and did not use the U.S. standard death certificate (2.0 vs. 1.9, p=0.90). We were unable to compare the percentage of women who were Asian/Pacific Islander due to the low number of deaths in this group.

Pregnancy-associated Homicide

There were 139 counts of pregnancy-associated homicide in our sample, yielding a pregnancy-associated homicide rate of 2.90 per 100,000 live births (Figure 3) and representing over half (59.7%) of the total pregnancy-associated violent deaths. 77.7% of the pregnancy-associated homicides occurred in pregnant women (vs. during the first year postpartum). Women at the extremes of the age range were at the highest risk of pregnancy-associated homicide. Mothers 24 and younger accounted for more than half (53.9%) of the pregnancy-associated homicides in our sample but make up only 1/3 (33.6%) of all live births in the NVDRS states(p<.01). In addition, victims of homicide were significantly more likely to be age 40 or older as compared to women with all live births in the NVDRS states. African-American mothers accounted for almost half (44.6%) of the pregnancy-associated homicides but only 17.7% of live births(p<.01). Victims of pregnancy-associated homicide were significantly more likely to be unmarried. The rate of pregnancy-associated homicide did not differ significantly between states that did and did not use the U.S. standard death certificate (3.0 vs. 3.7, p=0.22). We were unable to compare the percentage of women who were Asian/Pacific Islander or American Indian due to the low number of deaths in these groups.

Intimate Partner Violence

In pregnancy-associated suicides, 54.3% of victims experienced problems with a current or former intimate partner that appeared to have contributed to the suicide. 45.3% of pregnancy-associated homicides were associated with violence from a current or former intimate partner. 42.4% of suspects in pregnancy-associated homicides were a current or former intimate partner of the victim (n=59), and this is by definition IPV homicide. Similar to victims of all pregnancy-associated homicides, victims of pregnancy-associated intimate partner homicide were younger, with mothers 24 and younger accounting for 44.1% of intimate-partner homicides but only 33.6% of all live births, although this did not reach statistical significance (Table 2). African-American women accounted for 37.3% of pregnancy-associated intimate-partner homicides but only 17.7% of live births (p<.01). Victims of pregnancy-associated intimate partner homicide were significantly more likely to be unmarried as compared to all live births. We were unable to compare the percentage of women who were Asian/Pacific Islander or American Indian due to the low number of deaths in these groups.

Table 2.

Pregnancy-associated Homicides*: Demographics compared to all Live Births

| Pregnancy-Associated Homicidesb n (%) | Live Births n (%) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age | |||

| 15–19 | 22 (15.8) | 456,478 (9.5) | 0.01 |

| 20–24 | 53 (38.1) | 1,153,503 (24.1) | <.01 |

| 25–29 | 32 (23.0) | 1,296,074 (27.1) | 0.28 |

| 30–39 | 24 (17.3) | 1,746,560 (36.5) | <.01 |

| 40–54 | 8 (5.8) | 132,660 (2.8) | 0.03 |

|

| |||

| Race/Ethnicityc | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 57 (41.0) | 2,837,502 (59.4) | <.01 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 62 (44.6) | 845,448 (17.7) | <.01 |

| Hispanic | 14 (10.1) | 780,470 (16.3) | 0.05 |

|

| |||

| Unmarried | 106 (76.3) | 1,267,030 (34.7) | <.01 |

pregnancy-associated=deaths occurring during pregnancy or the first year postpartum

n=139

cells suppressed for other races due to low number of cases: Asian/Pacific Islander; American Indian

Conclusion

For many providers the term “maternal mortality” may conjure thoughts of “hemorrhage, clot, and infection”, consistent with traditional clinical training. Yet, the causes of maternal mortality have significantly shifted over time. Our results indicate that pregnancy-associated homicide and suicide each account for more deaths than many other obstetric complications, including hemorrhage, obstetric embolism, or preeclampsia/eclampsia, which may be thought of as more “traditional” causes of maternal mortality.(21) This is reflective of the fact that the causes of maternal mortality have significantly shifted, with improvement in mortality associated with many obstetrically-related events, but a steady rate of maternal mortality due to injury.(1) Our results also confirm the need to focus on the relationships between socio demographic disparities and intimate partner violence with pregnancy-associated violent death.

The demographic patterns in our study are similar to those found in NVDRS reports from the general population.(22)Among all female suicide victims, rates are highest in the 45–54 year age range and among Whites and women of American Indian descent. In the general population, women ages 20–24 have the highest rate of homicide, and African American women have the highest rate of homicide as compared to other race/ethnicities.(22)

Our results demonstrate somewhat higher maternal mortality rates than those previously demonstrated in a national perinatal sample.(23) Chang et al. reported a pregnancy-associated homicide rate of 1.7 deaths per 100,000 live births between 1991 and 1999 in the Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System (PMSS).(23)Suicides were even less common in their sample. These differences may reflect the data collection methods used by the two systems. The PMSS is designed to collect data on all pregnancy-associated deaths, regardless of cause. Reporting states use death certificate data and/or matched death-to-birth certificate data to identify deaths, and the PMSS utilizes maternal death, infant birth, and fetal death certificates in addition to autopsy or maternal mortality review committee reports to assign a cause of death.(23)The NVDRS is designed to collect data specifically associated with violent deaths. Abstractors code pregnancy and postpartum status based on findings from the victim’s death certificate and the medical examiner’s report. Cause of death is assigned based on data from death certificates, CME reports, and police reports.(18) Mortality rates from other smaller studies of pregnancy-associated violent death have been closer to our results for suicide deaths and have demonstrated even higher mortality rates for pregnancy-associated homicide.(4, 24–25)

Despite these differences in mortality rates between the NVDRS and PMSS, the characteristics of pregnancy-associated homicide victims between the NVDRS and others, including PMSS, are strikingly similar. Victims of pregnancy-associated are more likely to be Black, younger, and unmarried.(23–24) In addition, our finding of the association between intimate partner conflict and both pregnancy-associated homicide and suicide has been echoed by several studies in general and perinatal samples.(1–2, 17, 22, 24) In the NVDRS general population sample, over one half of female homicide deaths (59.1%) are associated with intimate partner violence, and over one-quarter of suicides in female victims (26.1%) were related to intimate partner problems.(22) In a postpartum study, 38% of female homicide victims were killed by a boyfriend, husband, or ex-husband.(26)

Our study has several limitations. While the NVDRS now collects data from many states, it is not fully nationally representative.(22) Furthermore, because of the low rates of deaths in certain subpopulations (Asian/Pacific Islander and American Indian), we were not able to compare data among all ethnic groups. NVDRS abstractors are limited by the completeness and quality of the reports they receive, and personnel, death certificates, and law enforcement protocols may vary from one jurisdiction to the next. For this reason, the NVDRS uses multiple complementary data sources and abstractors follow defined NVDRS primacy rules in coding data.(22) While the NVDRS codes pregnant and postpartum status from multiple data sources, pregnancy-associated deaths may still be underreported. Pregnancies, even if identified, may not be reported on death certificates, autopsies might not include examination for pregnancy(27), early-gestation and late-postpartum status may be missed on autopsy, and family members and friends may have been unaware of early or unwanted pregnancies. Other surveillance methods such as vital record linkage between death and birth certificates may enhance case ascertainment.(28) Also, because a majority of female deaths in the NVDRS are coded as “unknown” pregnancy or postpartum status (67.2%), our results may underestimate the number of pregnancy-associated violent deaths. In addition, we are unable to compare the rates of pregnancy-associated violent death in pregnant, postpartum versus nonpregnant, nonpostpartum women because so many deaths were classified as “unknown” status. Finally, protective factor data would be helpful but it is not collected by the NVDRS as reports associated with violent death often contain only circumstances associated with risk factors. Our data provides information regarding potential risk factors for maternal violent deaths but cannot prove causation. In addition, this analysis focus on demographic data and prevalence of intimate partner conflict among victims of pregnancy-associated violent data but did not cover all of the potential precipitating circumstances that may be related to violent death. Our future research will involve analyses of other potential precipitating circumstances around maternal violent death, including substance abuse, life stress, and mental health diagnoses and treatment.

Despite these limitations, our study highlights the unfortunate but important role of homicide and suicide as contributors to pregnancy-associated mortality. These findings suggest that effective prevention methods aimed at perinatal psychosocial health are imperative. Unlike some obstetric complications, violence is often potentially preventable. While studies have questioned the effectiveness of previous screening and prevention efforts related to homicide and to mental health/suicide(29–30), research is moving forward in developing evidence-based guidelines for perinatal depression care(31), identifying successful strategies for engaging and training perinatal healthcare providers in delivering mental health care(32–33)and engaging perinatal women in receiving mental healthcare services(34). Our findings also demonstrate the frequent association of intimate partner conflict with maternal violent death. IPV has been associated with adverse outcomes for both mother and baby, including preterm labor and low-birthweight, and may contribute to perinatal health disparities.(35) Studies suggest that standardized screening for IPV is associated with increased identification rates in pregnant women, and experts have made recommendations for further research in IPV interventions, including research into the role of culture on intervention effectiveness(36). In fact, a recent intervention was shown to lower recurrence risk for intimate partner violence victimization during pregnancy and the postpartum period (37). As the perinatal period is a time when health care providers have recurrent encounters with potentially at-risk women, providers can play a vital role in delivering interventions which may help to prevent violent deaths. With continued focus on this important national health concern and a continued push toward the development of effective psychosocial interventions, particularly post-screening care, we may be able to reduce the impact of this unfortunate killer on American women, their children, and their families.

Table 1.

Pregnancy-associated Suicides*: Demographics compared to all Live Births

| Pregnancy-Associated Suicidesa n (%) | Live Births n (%) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age | |||

| 15–19 | 12 (12.8) | 456,478 (9.5) | 0.27 |

| 20–24 | 18 (19.1) | 1,153,503 (24.1) | 0.26 |

| 25–29 | 19 (20.2) | 1,296,074 (27.1) | 0.13 |

| 30–39 | 29 (30.8) | 1,746,560 (36.5) | 0.25 |

| 40–54 | 16 (17.0) | 132,660 (2.8) | <.01 |

|

| |||

| Race/Ethnicityc | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 70 (74.5) | 2,837,502 (59.4) | <.01 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 11 (11.3) | 845,448 (17.7) | 0.10 |

| Hispanic | 7 (7.2) | 780,470 (16.3) | 0.02 |

| American Indian | 5 (5.1) | 76,131 (1.6) | <.01 |

|

| |||

| Unmarried | 57 (58.8) | 1,267,030 (34.7) | <.01 |

pregnancy-associated=deaths occurring during pregnancy or the first year postpartum

n=94

cells suppressed for other races due to low number of cases; Asian/Pacific Islander

Table 3.

Pregnancy-associated Intimate Partner Homicides*: Demographics compared to all Live Births

| Pregnancy-Associated Intimate Partner Homicidesa n (%) | Live Births n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age | |||

| 15–19 | 6 (10.2) | 456,478 (9.5) | 0.85 |

| 20–24 | 20 (33.9) | 1,153,503 (24.1) | 0.08 |

| 25–29 | 16 (27.1) | 1,296,074 (27.1) | 1.0 |

| 30–39 | 13 (22.0) | 1,746,560 (36.5) | 0.02 |

| 40–54 | b | 132,660 (2.8) | |

|

| |||

| Race/Ethnicityc | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 27 (45.8) | 2,837,502 (59.4) | 0.47 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 22 (37.3) | 845,448 (17.7) | <.01 |

| Hispanic | 6 (10.2) | 780,470 (16.3) | 0.20 |

|

| |||

| Unmarried | 41 (69.5) | 1,267,030 (34.7) | <.01 |

pregnancy-associated=deaths occurring during pregnancy or the first year postpartum

n=59

cell suppressed due to low number of cases

cells suppressed for other races due to low number of cases: Asian/Pacific Islander; American Indian

Acknowledgments

Financial support:

Data analysis for this project was funded under the primary author’s fellowship in the Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars Program. Manuscript preparation has been supported through the primary author’s appointment in the GHSU Education Discovery Institute.

The authors acknowledge the CDC National Violent Death Reporting System and Deborah Karch, PhD for providing the data for this study. The authors also wish to acknowledge the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the GHSU Education Discovery Institute for financial support of this work. The authors acknowledge Matthew Davis, MD, MAPP for research mentorship and study design assistance and the Education Discovery Institute Statistical Support Team (B Bodie; R Whitaker; M Villarosa) for statistical support associated with this project. This work was awarded the Steiner Young Investigator Award at the 2010 North American Society for Psychosocial Obstetrics and Gynecology (NASPOG) Meeting.

CDC-suggested disclaimer for manuscripts using NVDRS data:

This research uses data from the NVDRS, a surveillance system designed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. The findings are based, in part, on the contributions of 16 of the 17 funded states that collected violent death data and the contributions of the states’ partners, including personnel from law enforcement, vital records, medical examiners/coroners, and crime laboratories. The analyses, results, and conclusions presented here represent those of the authors and not necessarily those of CDC. Persons interested in obtaining data files from NVDRS should contact CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, 4770 Buford Hwy, NE, MS F-63, Atlanta, GA 30341-3717, (800) CDC-INFO (232-4636).

References

- 1.Shadigian E, Bauer ST. Pregnancy-associated death: a qualitative systematic review of homicide and suicide. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2005 Mar;60(3):183–90. doi: 10.1097/01.ogx.0000155967.72418.6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krulewitch CJ, Pierre-Louis ML, de Leon-Gomez R, Guy R, Green R. Hidden from view: violent deaths among pregnant women in the District of Columbia, 1988–1996. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2001 Jan-Feb;46(1):4–10. doi: 10.1016/s1526-9523(00)00096-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sachs BP, Brown DA, Driscoll SG, Schulman E, Acker D, Ransil BJ, et al. Maternal mortality in Massachusetts. Trends and prevention. N Engl J Med. 1987 Mar 12;316(11):667–72. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198703123161105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jocums SB, Berg CJ, Entman SS, Mitchell EF., Jr Post delivery mortality in Tennessee, 1989–1991. Obstet Gynecol. 1998 May;91(5 Pt 1):766–70. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nannini A, Weiss J, Goldstein R, Fogerty S. Pregnancy-associated mortality at the end of the twentieth century: Massachusetts, 1990–1999. J Am Med Womens Assoc. 2002 Summer;57(3):140–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harper M, Parsons L. Maternal deaths due to homicide and other injuries in North Carolina: 1992–1994. Obstet Gynecol. 1997 Dec;90(6):920–3. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(97)00485-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baker N, Fogarty C, Stroud D, Rochat R. Enhanced pregnancy-associated mortality surveillance: Minnesota, 1990–1999. Minn Med. 2004 Jan;87(1):45–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ho EM, Brown J, Graves W, Lindsay MK. Maternal death at an inner-city hospital, 1949–2000. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002 Nov;187(5):1213–6. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.127136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horon IL, Cheng D. Enhanced surveillance for pregnancy-associated mortality--Maryland, 1993–1998. Jama. 2001 Mar 21;285(11):1455–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.11.1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoyert DL. Maternal mortality and related concepts. Vital Health Stat. 2007 Feb;3(33):1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chambliss LR. Intimate partner violence and its implication for pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Jun;51(2):385–97. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e31816f29ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leiner AS, Compton MT, Houry D, Kaslow NJ. Intimate partner violence, psychological distress, and suicidality: A path model using data from African American women seeking care in an urban emergency department. J Fam Violence. 2008 Aug;23(6):473–81. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abbott J, Johnson R, Koziolmclain J, Lowenstein SR. DOMESTIC VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN -INCIDENCE AND PREVALENCE IN AN EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT POPULATION. JAMA-J Am Med Assoc. 1995 Jun;273(22):1763–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.273.22.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stark E, Flitcraft A. Killing the beast within: woman battering and female suicidality. Int J Health Serv. 1995;25(1):43–64. doi: 10.2190/H6V6-YP3K-QWK1-MK5D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seedat S, Stein MB, Forde DR. Association between physical partner violence, posttraumatic stress, childhood trauma, and suicide attempts in a community sample of women. Violence Vict. 2005;20(1):87–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pico-Alfonso MA, Garcia-Linares MI, Celda-Navarro N, Blasco-Ros C, Echeburua E, Martinez M. The impact of physical, psychological, and sexual intimate male partner violence on women’s mental health: Depressive symptoms, posttraumatic stress disorder, state anxiety, and suicide. J Womens Health. 2006 Jun;15(5):599–611. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin S, Macy R, Sullivan K, Magee M. Pregnancy-associated violent deaths: the role of intimate partner violence. Trauma, violence & abuse. 2007;8(2):135–48. doi: 10.1177/1524838007301223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS) Coding Manual Revised [Online] 2008. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (producer); [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kung H, Hoyert DL, Xu J, SLM Deaths: Preliminary data for 2005. Heath E-Stats. 2007 Sep; [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Vital Statistics System: Birth Data. [cited 2010 February 18]; Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/births.htm.

- 21.Xu J, Kochanek K, Murphy S, BT-V . Deaths: Final data for 2007. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karch DL, Lubell KM, Friday J, Patel N, Williams DD. Surveillance for violent deaths--National Violent Death Reporting System, 16 states, 2005. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2008 Apr 11;57(3):1–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang J, Berg CJ, Saltzman LE, Herndon J. Homicide: a leading cause of injury deaths among pregnant and postpartum women in the United States, 1991–1999. Am J Public Health. 2005 Mar;95(3):471–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.029868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheng D, Horon IL. Intimate-partner homicide among pregnant and postpartum women. Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Jun;115(6):1181–6. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181de0194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parsons LH, Harper MA. Violent maternal deaths in North Carolina. Obstet Gynecol. 1999 Dec;94(6):990–3. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(99)00466-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dietz PM, Rochat RW, Thompson BL, Berg CJ, Griffin GW. Differences in the risk of homicide and other fatal injuries between postpartum women and other women of childbearing age: implications for prevention. Am J Public Health. 1998 Apr;88(4):641–3. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.4.641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Office USGA. Violence Against Women: Data on Pregnant Victims and Effectiveness of Prevention Strategies are Limited. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pallin DJ, Sundaram V, Laraque F, Berenson L, Schomberg DR. Active surveillance of maternal mortality in New York City. Am J Public Health. 2002 Aug;92(8):1319–22. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.8.1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Family and Intimate Partner Violence: Recommendation Statement. 2004 [cited 2008 October 14, 2008]; Available from: http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/3rduspstf/famviolence/famviolrs.htm.

- 30.Paulden M, Palmer S, Hewitt C, Gilbody S. Screening for postnatal depression in primary care: cost effectiveness analysis. Bmj. 2009;339:b5203. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b5203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yonkers K, Wisner K, Stewart D, Oberlander T, Dell D, Stotland N, et al. The management of depression during pregnancy: a report from the American Psychiatric Association and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(3):703–13. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181ba0632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Flynn HA, O’Mahen HA, Massey L, Marcus S. The impact of a brief obstetrics clinic-based intervention on treatment use for perinatal depression. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2006 Dec;15(10):1195–204. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller L, Shade M, Vasireddy V. Beyond screening: assessment of perinatal depression in a perinatal care setting. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2009 Oct;12(5):329–34. doi: 10.1007/s00737-009-0082-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Flynn HA, Henshaw E, O’Mahen H, Forman J. Patient perspectives on improving the depression referral processes in obstetrics settings: a qualitative study. General Hospital Psychiatry. 32(1):9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sharps PW, Laughon K, Giangrande SK. Intimate partner violence and the childbearing year: maternal and infant health consequences. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2007 Apr;8(2):105–16. doi: 10.1177/1524838007302594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O’Reilly R, Beale B, Gillies D. Screening and intervention for domestic violence during pregnancy care: a systematic review. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2010 Oct;11(4):190–201. doi: 10.1177/1524838010378298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kiely M, El-Mohandes AAE, El-Khorazaty MN, Gantz MG. An Integrated Intervention to Reduce Intimate Partner Violence in Pregnancy A Randomized Controlled Trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Feb;115(2):273–83. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181cbd482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berg CJ, Callaghan WM, Henderson Z, Syverson C. Pregnancy-Related Mortality in the United States, 1998 to 2005. Obstet Gynecol. 2011 May;117(5):1230. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31821769ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]