Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common type of senile dementia, characterized by cognitive deficits related to degeneration of cholinergic neurons. The first anti-Alzheimer drugs approved by the Food and Drug Administration were the cholinesterase inhibitors (ChEIs), which are capable of improving cholinergic neurotransmission by inhibiting acetylcholinesterase. The most common ChEIs used to treat cognitive symptoms in mild to moderate AD are rivastigmine, galantamine, and donepezil. In particular, the lattermost drug has been widely used to treat AD patients worldwide because it is significantly less hepatotoxic and better tolerated than its predecessor, tetrahydroaminoacridine. It also demonstrates high selectivity towards acetylcholinesterase inhibition and has a long duration of action. The formulations available for donepezil are immediate release (5 or 10 mg), sustained release (23 mg), and orally disintegrating (5 or 10 mg) tablets, all of which are intended for oral-route administration. Since the oral donepezil therapy is associated with adverse events in the gastrointestinal system and in plasma fluctuations, an alternative route of administration, such as the transdermal one, has been recently attempted. The goal of this paper is to provide a critical overview of AD therapy with donepezil, focusing particularly on the advantages of the transdermal over the oral route of administration.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, donepezil, transdermal, patch

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common type of senile dementia, affecting 6%–8% of people over the age of 65 years and nearly 30% of people older than 85 years.1,2 In fact, it has been demonstrated that the number of people over 60 years old affected by AD doubles every 5 years.1,2 The common signs and symptoms of AD include apathy, agitation, irritability, disinhibition, delusions, mood disturbances, and aberrant motor behavior, as well as sleeping and eating abnormalities. Since this disease may progress in different ways, it has become difficult to make a precise diagnosis.3

AD is associated with reduced levels of a number of cerebral neurotransmitters such as acetylcholine (ACh), noradrenaline, serotonin, somatostatin, and corticotrophin-releasing factors, whereas the levels of glutamate increase.4 However, the cognitive deficits seem to be primarily related to the degeneration of cholinergic neurons that originate in the basal-forebrain-cholinergic system and innervate the neocortex, hippocampus, and other brain areas.5 Thus, AD treatment entails the restoration of cholinergic pathway neurotransmitters through several approaches such as exploitation of ACh precursors (eg, lecithin or choline), using muscarinic or nicotinic agonists (eg, bethanacol, arecoline, and milameline), as well as administering cholinesterase inhibitors (ChEIs).6–8 ChEIs, the first class of anti-AD drugs approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA), reduce the hydrolysis of acetylcholine in the synaptic cleft by inhibiting cholinesterase (acetylcholinesterase [AChE] and/or butyrylcholinesterase [BuChE]). This inhibition increases the ACh levels and therefore improves neurotransmission.9 Since AChE is found predominantly in the brain, striated muscle, and erythrocytes, while BuChE is mainly found in the periphery (skin, plasma, and cardiac muscle), AD treatment strategies are mainly directed towards the inhibition of AChE.10,11 It is worth mentioning that these agents may not be effective in all patients because only 50% of AD patients have cholinergic deficits. Indeed, 30% of AD patients are also characterized by noradrenaline deficits.10

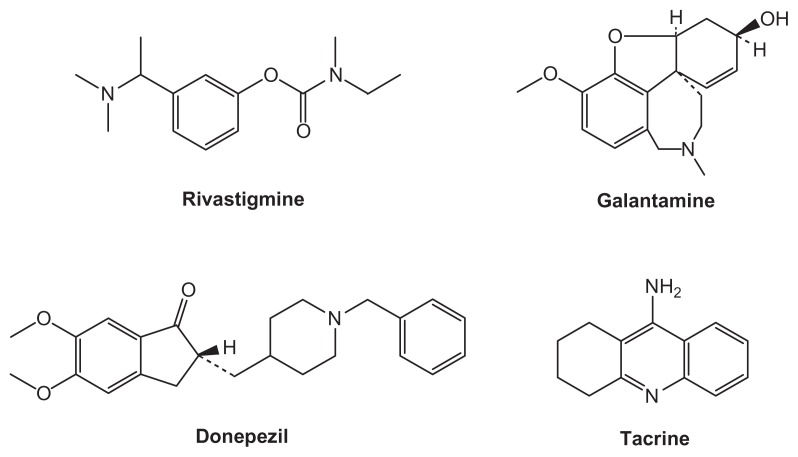

Four ChEIs are commonly used to treat cognitive symptoms in mild to moderate AD: Exelon® (rivastigmine tartrate; Novartis AG, Basel, Switzerland); Reminyl® ( galantamine hydrobromide; Johnson and Johnson Inc, New Brunswick, NJ); Aricept® (donepezil hydrochloride; Pfizer Inc, New York, NY; Eisai Inc, Tokyo, Japan); and the rarely prescribed Cognex® (tacrine hydrochloride; First Horizon Pharmaceutical Corp., Roswell, GA) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Structure of ChEIs.

Abbreviation: ChEIs, cholinesterase inhibitors.

The goal of this paper is to provide a critical overview of donepezil as an AD therapy, focusing particularly on the advantages of transdermal over the oral route of administration.

Oral donepezil therapy

Immediate-release tablets

Donepezil immediate-release (IR) tablets (5 or 10 mg) were approved for use in the US in November 1996 for the treatment of dementia of the Alzheimer’s type.12 Donepezil interacts with AChE via hydrogen bonds and is demonstrated to be a reversible, non-competitive, and selective ChEI that produces long-lasting inhibition of brain AChE without markedly affecting peripheral AChE activity.13 Due to properties such as low hepatotoxicity, high selectivity towards AChE inhibition (IC50 AChE/IC50 BuChE = 6.7/7400 nM), and a duration of action (t1/2 = 90 h) that is sufficiently long enough to allow for convenient once-daily administration, donepezil has been widely used to treat AD patients worldwide.14 The long-term benefits and good safety profile of AChEIs shown by extended post-marketing studies allowed for the approval of donepezil for the treatment of the entire clinical spectra of the disease in 2007.15,16

The recommended dosage for donepezil IR is 5 mg/day for the first 4 weeks and 10 mg/day thereafter.17 Inactive ingredients in 5 and 10 mg tablets are lactose monohydrate, corn starch, microcrystalline cellulose, hydroxypropyl cellulose, and magnesium stearate. The film coating contains talc, polyethylene glycol, hypromellose, and titanium dioxide.13 The efficacy of donepezil was demonstrated both in a 24-week, double-blind study and in a placebo-controlled trial (the AD2000 study).18 In the former study, patients with mild to moderate AD were randomly treated with donepezil 5 mg/day, 10 mg/day, or placebo. Patients’ cognition and clinicians’ global ratings (AD Assessment Scale [ADAS-cog] and the Clinician’s Interview Based Assessment of Change-Plus [CIBC], respectively) were significantly improved in patients treated with the drug compared with placebo, whereas no improvement was noted on patient-related quality of life.19,20 In the latter study, 565 patients with mild to moderate AD were enrolled; in both the presence and absence of cerebrovascular disease, donepezil has been shown to improve cognition compared with placebo. In particular, the ratio of “improved” patients (as judged by the clinicians) across the presence of hallucinations, delusions, wandering, and aggression at last observation carried forward among patients receiving donepezil, and ranged between 59.6% and 65.6%.21 For these reasons, donepezil may be a useful treatment not only for the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD), but also for cognitive dysfunction.

Sustained-release tablets

In 2010, the FDA approved sustained-release (SR) tablets containing 23 mg of donepezil to provide a higher once-daily dose while avoiding a sharp daily increase in peak concentration. Inactive ingredients in the 23 mg tablets are ethylcellulose, hydroxypropyl cellulose, lactose monohydrate, magnesium stearate, and methacrylic acid copolymer, type C. The film coating is composed of ferric oxide, hypromellose 2910, PEG 8000, talc, and titanium dioxide. These film-coated tablets were compared with the marketed formulation of 10 mg IR tablets in patients with moderate to severe AD who were on a stable dose of 10 mg/day Aricept® for at least 3 months before screening.22 The 1500 enrolled patients received either 10 mg donepezil IR in combination with the placebo corresponding to the 23 mg donepezil SR formulation, or 23 mg donepezil SR in combination with the placebo corresponding to 10 mg of the donepezil IR formulation. The 23 mg donepezil SR ensured significant cognitive and global functioning benefits, but safety and efficacy of long-term administration are still under study.23,24

Orally disintegrating tablets

Aricept® is also available as an orally disintegrating tablet (ODT), approved for use in the US in 2004. This formation is particularly useful for patients who have difficulties swallowing tablets; moreover, they allow for administration once daily. These tablets contain 5 or 10 mg of donepezil hydrochloride, carrageenan, mannitol, colloidal silicon dioxide, and polyvinyl alcohol. The 10 mg tablets also contain ferric oxide (yellow) as a coloring agent.25

Adverse events associated with oral donepezil therapy

The most frequent adverse events (AEs) of donepezil, as well as other ChEIs, are cholinergic effects related to the gastrointestinal system (nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea), and sleep disturbances, the frequency and severity of which depends on the chosen dose.26,27 Less common adverse effects are vagotonia (eg, bradycardia, syncope), and central nervous system (eg, aggression, sleep disturbance) and parasympathetically mediated (eg, urinary incontinence) AEs.28

The incidence of AEs increases with oral administration due to the large and frequent plasma fluctuations. In fact, when donepezil is administered orally, it is rapidly absorbed through the gastrointestinal wall thus reaching its peak plasma level (Cmax). The drug levels then decrease until the next dose is admnistered.9 In order to decrease both the Cmax level and the rate of Cmax achievement so as to attenuate the AEs, the alternative route of transdermal administration was attempted.

Transdermal route versus oral route

The transdermal drug delivery route has several advantages compared to the parenteral and oral routes of administration, especially in the elderly.29 Indeed, this type of administration is particularly useful when a chronic neurological disorder is present because it allows for the circumvention of the patient’s unwillingness (or incapability) to swallow, and the patient can be treated with intramuscular injections or intravenous infusions. Moreover, it provides stable drug blood levels over an extended period of time and improves patient compliance, because a patient does not have to remember to take his or her medication or carry pills for further administrations later in the day.30 The transdermal drug delivery route also offers other advantages with respect to other traditional approaches, as reported in Table 1.31

Table 1.

Advantages of the transdermal drug delivery route

|

The main disadvantages of transdermal delivery include potential skin sensitization or irritation, discomfort caused by adhesives, imperfect adhesion to the skin, and its high cost. Moreover, since the skin is resistant to drug penetration, only drugs that do not require high blood concentrations can be administered by means of the transdermal route.32–34

Human skin

The human skin is designed to protect an organism from the external environment and is effective as a barrier to chemical transport. It is a complex multilayer organ with a total thickness of 2–3 mm, formed by panniculus adiposus, dermis, epidermis, and stratum corneum. The panniculus adiposus, a variably thick fatty layer, is situated below the dermis. The dermis is a layer of dense connective tissue that supports the epidermis. The epidermis (about 100 μm thick) comprises a layer of epithelial cells and is composed of different layers, the outermost being the stratum corneum. The statum corneum (15–20 μm thick) comprises highly dense and keratinized tissue and is the skin’s main source of penetration and permeation resistance.35,36

The capacity of a drug to penetrate the skin is an important issue for clinical relevance of transdermal delivery systems. Indeed, only approximately 1 mg of a drug is delivered across a 1 cm area of skin in 24 hours.37,38

The efficiency and rate of absorption of a drug through the skin depends on many biological and physiochemical factors. Lipophilic agents may pass rapidly across the stratum corneum through the lipid-rich intercellular space, whereas hydrophilic agents must dissolve and diffuse in cellular bound water molecules.39 The molecular size of the agent is also an important factor in determining the suitability for transdermal delivery; smaller molecules tend to be absorbed faster than larger ones, with very large molecules such as insulin (5808 Da) being too large to pass through the skin. It has been suggested that any compound with a molecular weight above 500 Da is unlikely to be suitable for transdermal delivery.40

Transdermal patch

Transdermal patches are medicated adhesive systems capable of ensuring a systemic effect of the drug and modulate its transport through the skin on demand. In order to achieve this goal, it is important to consider drug, skin, and patch properties (Table 2).

Table 2.

Factors influencing transdermal drug administration

|

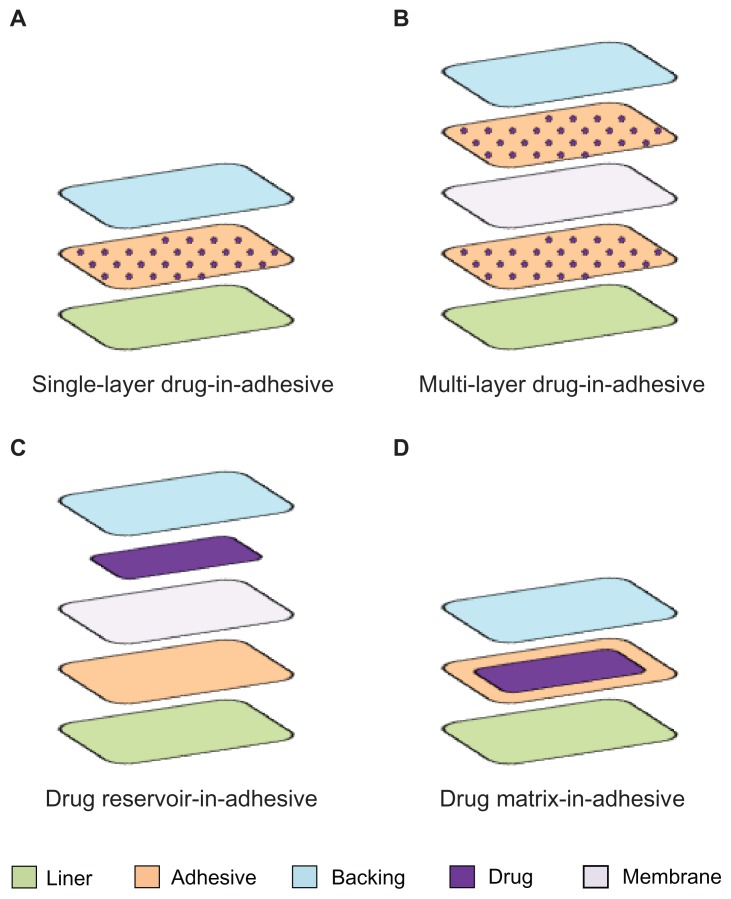

Transdermal patches consist of several components. By proceeding from the visible external surface inward to the surface apposed to the skin, it is possible to distinguish between: (1) an impermeable backing; (2) a membrane able to control the drug release; (3) a pressure sensitive adhesive to hold the patch in place on the skin; and (4) a protective cover that is peeled away before applying the patch (Table 3).41 The patches belong to one of the following four general types.

Table 3.

Patch components

| Component | Function |

|---|---|

| Backing | Protects the patch from the outer environment, is impermeable to the transdermal patch components, and provides the patch with its flexibility. It is made of elastomers (polyolefin oils, polyester, polyethylene, polyvinylidene chloride and polyurethane) and is preferably nonbreathable (by adding aluminum foil).30 |

| Membrane | Controls the release of the drug. It is made of natural or synthetic polymer or synthetic elastomers, and its thickness ranges from about 2 mm to about 7 mm. |

| Adhesive | It binds the components of the patch together and the patch to the skin. It is composed by silicone, rubber, polyvinylacetate, or polyisobutylene, depending on the skin–adhesion properties desired. It may contain permeation enhancers (solvents, surfactants or miscellaneous chemicals) to promote skin permeability by altering its structure.34 |

| Liner | Protects the patch during storage and is peeled off before use. |

Single-layer drug-in-adhesive

In this patch, the drug is contained into the adhesive layer that not only serves to adhere both the various layers of the patch together and the entire system to the skin, but it is also responsible for releasing the drug. The adhesive layer is surrounded by a temporary liner and a backing (Figure 2A). The rate of release of the drug from this type of system depends on the diffusion across the skin.

Figure 2.

Representation of different types of patches.

Multi-layer drug-in-adhesive

This type is very similar to the single layer, but it presents two drug-containing adhesive layers, usually separated by a membrane (but not in all cases) (Figure 2B). This patch allows for the administration of different drugs with the same system.

Drug reservoir-in-adhesive

The drug layer is a liquid compartment (solution or suspension) separated from the adhesive layer by a semi-permeable membrane, and the rate of release follows a zero order (Figure 2C).

Drug matrix-in-adhesive

The matrix system is characterized by the inclusion of a semisolid matrix containing the drug (in solution or suspension), which is in direct contact with the release liner. The adhesive layer is concentric with respect to the matrix (Figure 2D).

Transdermal donepezil therapy

As a small (molecular weight of 379.5) and lipophilic (Log P value of 3.08–4.11) molecule, donepezil is considered to be physicochemically well-suited for transdermal delivery.42–44 Valia et al30 proposed two types of transdermal delivery systems of donepezil: a drug reservoir-in-adhesive and a drug matrix-in-adhesive. The first reservoir-type patch is comprised of a backing film, a drug reservoir, a delivery rate-controlling membrane, and an adhesive layer that contacts the skin. The other type comprises a backing film, an adhesive layer comprising a matrix type adhesive and a protective liner. This second embodiment reduces the lag time during which the donepezil would otherwise migrate from the drug reservoir into and through the adhesive layer, and thus results in a faster influx of the drug into the patient’s blood stream upon application to the patient’s skin.

In contrast to the tablets that contain donepezil hydrochloride, the transdermal form of the drug is used as free base in order to obtain the desired delivery rates. As a matter of fact, the hydrophilic donepezil hydrochloride has low skin permeability and, although penetration enhancers can be used in order to favor drug penetration, it is not suitable for transdermal delivery.

The patches deliver donepezil through normal skin contact into the patient’s blood stream in the range of about 0.5 μg/cm2/hour to about 20 μg/cm2/hour or from about 3 μg/cm2/hour to about 13 μg/cm2/hour. The dosage is controlled by the active surface of the patch that comes in contact with the skin, and it can be adjusted by prescribing a patch with a larger or smaller active surface area.30 Dose size and frequency should be determined by a trained medical professional and depend on many factors, including patient weight and disease severity. The permeation rate of the donepezil from patches are regulated in such a way that blood-plasma levels obtained in the patient are comparable to the FDA approved blood-plasma levels obtained by oral administration. Patches of donepezil are applied for a period of 1 to 7 days, depending on the severity of the disease and the patient’s ability to remember to remove depleted patches and apply new ones.

Eisai Co, Ltd, the maker of Aricept® in Japan, is currently focusing on clinical development programs for Aricept®, the major innovations being transdermal patches directed to people with Alzheimer’s disease. Phase II clinical trials of a once-a-week transdermal patch formulation of donepezil (which includes a bioequivalence study comparing the currently marketed formulation of donepezil to the transdermal formulation) were conducted in 2009 by Teikoku Pharma USA, Inc (San Jose, CA).45 This study was designed to assess skin irritation, skin tolerability, and adhesion of the 350 mg donepezil transdermal patch system on the skin of elderly subjects with Alzheimer’s disease who have been on an established, well tolerated oral dose of Aricept® 10 mg, for a period of at least 2 months.45 The total application time for the donepezil transdermal patch system is 21 days, which was calculated by dividing the dosage into three 7-day applications to three separate areas of the body (upper back, upper middle arm, and side of torso).

A Phase I clinical trial of the donepezil single dose patch formulation was conducted in 2010 by Eisai Co, Ltd, to compare the pharmacokinetics of the donepezil patch (type A, B, C, D, E) with a single dose of donepezil 5 mg tablets.46 In addition, Eisai Co, Ltd, conducted a Phase I study in 2011 to evaluate the safety and tolerability of donepezil 16 mg tape when applied repeatedly for 17 days. The treatment was intended to be administered in 2 periods, Period 1 and Period 2. In Period 1, the 5 mg donepezil tablets were administered in a single dose. In Period 2, the tape containing 16 mg of donepezil (which corresponds to the 5 mg donepezil tablet) was applied without interruption for 17 days. A washout period of at least 8 days was followed between Periods 1 and 2. A posttreatment examination was performed at least 21 days after the last removal of the tape in Period 2.47 The results have not yet been published.

In February 2010, Eisai Co, Ltd, concluded license and option agreements with Teikoku Pharma USA regarding the development and marketing of a donepezil patch formulation. In September 2010, the US FDA agreed to review the New Drug Application (NDA) of a weekly transdermal patch formulation (a once-weekly administration formulation) of Aricept®.48 This NDA was submitted to the FDA for approval of the treatment for mild, moderate, and severe stages of Alzheimer’s disease. The new formulation, if approved, would be marketed by Eisai US, a subsidiary of Eisai Inc, and co-promoted with Pfizer Inc.

In April 2011, the FDA declined approval for the transdermal patch formulation of Eisai’s Alzheimer’s treatment Aricept®. Even if Teikoku Pharma USA decided to withdraw the NDA on April 17, 2012, Eisai and Teikoku Seiyaku will continue to move forward with the development of a once-daily Aricept® transdermal system (Phase I) for the Japanese market based on the exclusive license agreement between the two companies concerning Japan research, development, and marketing rights.49

Conclusion

Currently, the first choice for the treatment of AD focuses on reducing the cholinergic deficiency in the CNS with ChEIs (tacrine, rivastigmine, donepezil, and galantamine), which compensates for the deficiency of ACh in the CNS. Donepezil is a reversible, noncompetitive, and selective inhibitor of brain AChE. It is available in 5 and 10 mg conventional immediate-release tablets, 23 mg sustained-release formulation, and a new dry syrup formulation (under regulatory review).

The large fluctuation of plasma levels after oral administration of donepezil were associated with frequent gastrointestinal symptoms including diarrhea, nausea, constipation, abdominal pain, vomiting, anorexia, and abdominal distention. A transdermal drug delivery system may offer considerable advantages over conventional delivery methods of ChEI for patients who have difficulties swallowing solids or liquids. Furthermore, certain adverse effects may be decreased by this route of administration; for example, first pass effects could be avoided, plasma level fluctuations could be greatly reduced, and the dosing schedule can be simplified. Moreover, when adverse side effects occur, prompt cessation of drug delivery can be obtained by simple patch removal. These improved tolerability and compliance profiles could potentially result in greater treatment adherence, and the patch might be favored over the oral route by the majority of caregivers in the near future.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest and received no payments in the preparation of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Small GW, Rabins PV, Barry PP, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of Alzheimer disease and related disorders. Consensus statement of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, the Alzheimer’s Association, and the American Geriatrics Society. JAMA. 1997;278(16):1363–1371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bryne GJ. Treatment of cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s disease. Australian Journal of Hospital Pharmacy. 1998;28:261–266. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dooley M, Lamb HM. Donepezil: a review of its use in Alzheimer’s disease. Drugs Aging. 2000;16(3):199–226. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200016030-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan AL, Chien YW, Jin Lin S. Transdermal delivery of treatment for Alzheimer’s disease: development, clinical performance and future prospects. Drugs Aging. 2008;25(9):761–775. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200825090-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cutler NR, Sramek JJ. The role of bridging studies in the development of cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer’s disease. CNS Drugs. 1998;10(5):355–364. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brodaty H. Realistic expectations for the management of Alzheimer’s disease. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 1999;9(Suppl 2):S43–S52. doi: 10.1016/s0924-977x(98)00044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schachter AS, Davis KL. Guidelines for the appropriate use of cholinesterase inhibitors in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. CNS Drugs. 1999;11:281–288. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giacobini E. Cholinesterase inhibitors stabilize Alzheimer’s disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;920:321–327. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kurz A, Farlow M, Lefevre G. Pharmacokinetics of a novel transdermal rivastigmine patch for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: a review. Int J Clin Pract. 2009;63(5):799–805. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2009.02052.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lamy PP. The role of cholinesterase inhibitors in Alzheimer’s disease. CNS Drugs. 1994;1:146–165. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sramek JJ, Cutler NR. Recent developments in the drug treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Drugs Aging. 1999;14(5):359–373. doi: 10.2165/00002512-199914050-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Black SE, Doody R, Li H, et al. Donepezil preserves cognition and global function in patients with severe Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2007;69(5):459–469. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000266627.96040.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Di Stefano A, Iannitelli A, Laserra S, Sozio P. Drug delivery strategies for Alzheimer’s disease treatment. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2011;8(5):581–603. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2011.561311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takeda M, Tanaka T, Okochi M. New drugs for Alzheimer’s disease in Japan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;65(5):399–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2011.02253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Winblad B, Jelic V. Long-term treatment of Alzheimer disease: efficacy and safety of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2004;18(Suppl 1):S2–S8. doi: 10.1097/01.wad.0000127495.10774.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jelic V, Darreh-Shori T. Donepezil: a review of pharmacological characteristics and role in the management of Alzheimer disease. Clinical Medical Insights: Therapeutics. 2010;2:771–788. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bassil N, Grossberg GT. Novel regimens and delivery systems in the pharmacological treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. CNS Drugs. 2009;23(4):293–307. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200923040-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.University of Birmingham. AD2000 study [homepage on the Internet] Birmingham, UK: University of Birmingham; [Accessed May 30, 2012]. Available from: http://www.ad2000.bham.ac.uk/ [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rogers SL, Farlow MR, Doody RS, Mohs R, Friedhoff LT. A 24-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of donepezil in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Donepezil Study Group. Neurology. 1998;50(1):136–145. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.1.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weyer G, Erzigkeit H, Kanowski S, Ihl R, Hadler D. Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale: reliability and validity in a multicenter clinical trial. Int Psychogeriatr. 1997;9(2):123–138. doi: 10.1017/s1041610297004298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tanaka T, Kazui H, Morihara T, Sadik G, Kudo T, Takeda M. Post-marketing survey of donepezil hydrochloride in Japanese patients with Alzheimer’s disease with behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) Psychogeriatrics. 2008;8(3):114–123. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eisai Inc. ClinicalTrialsgov [website on the Internet] Bethesda, MD: US National Library of Medicine; 2007. [Accessed April 25, 2011]. Comparison of 23 mg donepezil sustained release (SR) to 10 mg donepezil immediate release (IR) in patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease. [updated April 25, 2010]. Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00478205. NLM identifier: NCT00478205. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Farlow MR, Salloway S, Tariot PN, et al. Effectiveness and tolerability of high-dose (23 mg/d) versus standard-dose (10 mg/d) donepezil in moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease: a 24-week, randomized, double-blind study. Clin Ther. 2010;32(7):1234–1251. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2010.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.For Eisai Inc. ClinicalTrials gov [website on the Internet] Bethesda, MD: ClinicalTrialsgov, US National Library of Medicine; 2007. [Accessed October 28, 2011]. Open-label extension study of 23 mg donepezil SR in patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease. [updated May 16, 2012]. Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00566501. NLM identifier: NCT00566501. [Google Scholar]

- 25.US Food and Drug Administration Aricept® ODTs [document on the Internet] Silver Spring, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; [Accessed. August 10, 2012]. Available from: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2006/020690s026,021720s003lbl.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seltzer B. Donepezil: an update. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2007;8(7):1011–1023. doi: 10.1517/14656566.8.7.1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Farlow M, Veloso F, Moline M, et al. Safety and tolerability of donepezil 23 mg in moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease. BMC Neurol. 2011;11:57. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-11-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Farlow MR, Alva G, Meng X, Olin JT. A 25-week, open-label trial investigating rivastigmine transdermal patches with concomitant memantine in mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease: a post hoc analysis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26(2):263–269. doi: 10.1185/03007990903434914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Priano L, Gasco MR, Mauro A. Transdermal treatment options for neurological disorders: impact on the elderly. Drugs Aging. 2006;23(5):357–375. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200623050-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Valia KH, Ramaraju VS, inventors. Core Tech Solutions, assignee. Transdermal methods and systems for treating Alzheimer’s disease. US 20080044461A1. United States patent. 2008 Feb 21;

- 31.Bhowmik D, Chiranjib BD, Chandira M, Jayakar B, Sampath KP. Recent advances in transdermal drug delivery system. Int J PharmTech Res. 2010;2(1):68–77. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oertel W, Ross JS, Eggert K, Adler G. Rationale for transdermal drug administration in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2007;69(4 Suppl 1):S4–S9. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000281845.40390.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tanner T, Marks R. Delivering drugs by the transdermal route: review and comment. Skin Res Technol. 2008;14(3):249–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0846.2008.00316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chanukya Kumar G. A review on transdermal therapeutics system. IJPT. 2011;3(3):1367–1381. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Montagna W, Parakkal PF. The Structure and Function of Skin. 3rd ed. New York: Academic Press; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holbroock KA, Wolff K. The structure and development of skin. In: Fitzpatrick TB, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, Freedberg IM, Austen KF, editors. Dermatology in General Medicine. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1993. pp. 97–145. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bonina FP, Puglia C, Barbuzzi T, et al. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of polyoxyethylene esters as dermal prodrugs of ketoprofen, naproxen and diclofenac. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2001;14(2):123–134. doi: 10.1016/s0928-0987(01)00163-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ghosh TK, Pfister WR. Transdermal and topical delivery systems: an overview and future trends. In: Ghosh TK, Pfister WR, Yum SI, editors. Transdermal and Topical Drug Delivery Systems. Illinois: Interpharm Press; 1997. pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nitti VW, Sanders S, Staskin DR, et al. Transdermal delivery of drugs for urologic applications: basic principles and applications. Urology. 2006;67(4):657–664. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bos JD, Meinardi MM. The 500 Dalton rule for the skin penetration of chemical compounds and drugs. Exp Dermatol. 2000;9(3):165–169. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0625.2000.009003165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mbah CJ, Uzor PF, Omeje EO. Perspectives on transdermal drug delivery. J Chem Pharm Res. 2011;3(3):680–700. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thevis M, Wilkens F, Geyer H, Schänzer W. Determination of therapeutics with growth-hormone secretagogue activity in human urine for doping control purposes. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2006;20(22):3393–3402. doi: 10.1002/rcm.2758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xia Z, Jiang X, Mu X, Chen H. Improvement of microemulsion electrokinetic chromatography for measuring octanol-water partition coefficients. Electrophoresis. 2008;29(4):835–842. doi: 10.1002/elps.200700104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Choi J, Choi MK, Chonga S, Chung SJ, Shima CK, Kim DD. Effect of fatty acids on the transdermal delivery of donepezil: in vitro and in vivo evaluation. Int J Pharm. 2012;422(1–2):83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Teikoku Pharma USA. ClinicalTrialsgov [website on the Internet] Bethesda, MD: US National Library of Medicine; 2009. [Accessed November 3, 2011]. Study in elderly Alzheimer’s subjects 3 consecutive 7-day applications of 350 mg DTP-Donepezil Transdermal Patch-System (DTP-System) [updated June 15, 2012]. Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/study/NCT00916383. NLM identifier: NCT00916383. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Eisai Co, Ltd. ClinicalTrials.gov [website on the Internet] Bethesda, MD: US National Library of Medicine; 2010. [Accessed August 11, 2011]. E2022 patch formulation single dose Phase I study. [updated August 11, 2011]. Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/study/NCT01253434. NLM identifier: NCT01253434. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eisai Co, Ltd. ClinicalTrials.gov [website on the Internet] Bethesda, MD: US National Library of Medicine; 2011. [Accessed May 30, 2012]. E2022 patch formulation multiple dose study. [updated May 30, 2012]. Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01450839. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dementia and Alzheimer’s Weekly [homepage on the Internet] New York: Alzheimer’s Weekly LLC; [Accessed August 10, 2012]. Once-weekly transdermal patch formulation. Available from: http://alzheimersweekly.com/content/testing-aricept-variations. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eisai Co, Ltd. Eisai amends license agreement with Teikoku Pharma USA for ARICEPT® transdermal patch system [news release] Tokyo: Eisai Co, Ltd; 2012. [Accessed May 21, 2012]. [April 20]. Available from: http://www.eisai.com/news/enews201217pdf.pdf. [Google Scholar]