Abstract

While India boasts the largest collective experience in the surgical management of TMJ ankylosis, times are changing and Indian Surgeons will need to begin thinking about other TMJ disorders that have previously gone under the radar. A growing Indian middle class with greater access to health facilities will demand treatment for TMJ disorders like myofacial pain and dysfunction, internal derangement and osteoarthrosis which Oral & Maxillofacial Surgeons must be prepared to manage. The aim of this paper is to review the role of TMJ surgery and its place in the treatment armamentarium of temporomandibular disorders. Indications, rationale for surgery, risks vs benefits are discussed and complemented with examples of clinical cases treated by the author. As India moves up the economic ladder of success, TMJ disorders that have largely been confined to Western nations will begin to appear in the rising middle classes of India. Indian Oral & Maxillofacial Surgeons must be prepared to recognize and manage disorders which present with more complex symptomatology where the role of TMJ surgery is less clear cut.

Keywords: Temporomandibular joint, Surgery, Arthroscopy, Indications, Techniques, Risks

Introduction

Over the last two decades, India has made extraordinary progress since it deregulated its domestic economy and opened its markets to the world. The result has been an ongoing economic success story with remarkable economic growth rate never before experienced since its independence in 1947. In the 21st Century, India has become an economic powerhouse and provides information technology services to the rest of the world. As a result, the burgeoning middle class of India will grow and present new temporomandibular joint (TMJ) problems to the practicing Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeon who, up until now, has been trained specifically for the surgical management of TMJ ankylosis. As India moves up the economic ladder of success, TMJ disorders that have largely been confined to Western nations will begin to appear in the rising middle classes of India. Indian oral and maxillofacial surgeons must be prepared to recognize and manage disorders which present with more complex symptomatology where the role of TMJ is less clear cut.

While TMJ ankylosis is challenging from a surgical perspective, the diagnosis is relatively simple and the surgical aims are straight forward. However, when it comes to TMJ internal derangement and osteoarthrosis, the diagnosis is often complicated and the surgical aims are less clearly defined. In the Western world, ready access to health care means that people expect even the most minor ailments to be managed by health professionals. This is in stark contrast to developing nations where access to health care may mean at least a day’s walk to the nearest health centre, so that only the most major ailments such as TMJ ankylosis present to the oral and maxillofacial surgeon.

The time has now come for Indian oral and maxillofacial surgeons to begin thinking about other TMJ disorders that afflict more than 5 % of the Western population who seek professional help. The rising middle class of India will not only have better access to health care facilities, but will demand treatment for ailments that in the past have been largely ignored because of poor resources and lack of facilities. The aim of this paper is to review common temporomandibular disorders (TMD) encountered in the Western World so that Indian oral and maxillofacial surgeons can begin to think about TMJ disorders beyond the surgical management of TMJ ankylosis.

TMDs

TMDs are sometimes encountered in Dental practice when patients may complain of cramp like pain in their masticatory muscles or painful clicking in their TMJs which may have been exacerbated by lengthy dental procedures. While most patients recover with simple measures such as jaw rest and soft diet, others require professional care that may involve any combination of occlusal splint therapy, physiotherapy and medications. Of the TMD patients who seek professional care, only about 5 % harbour a functional or pathological problem in their TMJ which may be amenable to surgery [1–5].

While occlusal splint therapy is pivotal to the management of most TMD [2], there is a small but important role of surgery [4] in the management of TMD. As far as the surgical management of joint disease is concerned, the Western world regards TMJ arthrocentesis as the panacea for all disorders regardless of how significant the joint disease may be. Regrettably, many practitioners fail to realise that TMJ arthrocentesis has limited applications, such as acute onset closed lock, and cannot treat advanced joint disease [1]. The problem in the Western world has been the lack of consensus about the role of surgery in the management of select TMD cases and so patients are seldom given the option of surgery.

A failure to appreciate surgical joint pathology by the TMD clinician may result in a concoction of non-surgical therapies that fail to address the patient’s intra-articular disease [2]. Eventually, patients may become disheartened by the lack of progress and spiral into a vicious cycle of anxiety and depression as they are led to believe that there is nothing more that can be done for them. In a small number of these patients TMJ surgery may well be the answer, but the lack of familiarity on the treating clinician’s part makes them reluctant to refer the patient for surgery. The role of TMJ surgery and its place in the treatment armamentarium of TMD will be reviewed, using clinical cases treated by the author as a means of illustrating the benefits of surgery in select patients.

The Rationale for TMJ Surgery

While surgery is often considered as an option of last resort, there are instances where surgery is the definitive and sometimes the only treatment option [3, 4]. In a fundamental sense, surgery is used to restore and repair damaged tissue or remove tissue that cannot be salvaged. Surgery is also used to promote healing of tissues by replacing missing tissues with grafts [4, 5]. It is ludicrous to suppose, for example, that a chronically displaced disc can be reduced by indirect, non-surgical therapies. Equally doubtful is the non-surgical management of collapsed articular cartilage and osteophytes that interfere with the smooth, pain-free function of the joint. These are just two common examples where surgery plays a pivotal role.

Where there is significant disease in the joint, in many cases, surgery is the definitive treatment modality [5]. A clear understanding of joint pathology and the role that surgery plays in the management of joint disease are indispensable requirements for all successful oral and maxillofacial surgeons who have an interest in TMJ disorders. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has provided us with a fascinating view of the TMJ [6] and there is little excuse on the part of all TMD practitioners, in particular, not to familiarise themselves with this useful investigative modality. The right combination of symptomatic history, clinical features and radiological signs will readily reveal whether the TMD patient is an appropriate candidate for surgery [3].

In the ideal world, the role of surgery should be subject to the scrutiny of scientific clinical trials. Unfortunately, unlike pharmacotherapy, clinical trials involving surgery, where the benefits are compared to placebo, cannot be undertaken for obvious ethical reasons [7]. We cannot perform “sham” operations to determine if the proposed surgery undertaken is better than a placebo response. As far as TMJ surgery is concerned, we must rely on best available evidence that has appeared in the literature over the past 4 decades [3, 7, 8].

Indications for TMJ Surgery (Table 1)

Table 1.

Indications for TMJ arthrotomy

| Absolute indications |

| Ankylosis—e.g. Fibrous or osseous joint fusion |

| Neoplasia—e.g. Osteochondroma of the condyle |

| Dislocation—i.e. Recurrent or chronic |

| Developmental disorders—e.g. Condylar hyperplasia |

| Relative indications |

| Internal derangement |

| Osteoarthrosis |

| Trauma |

| General Indications |

| Disorder not responding to non-surgical therapy |

| Where the TMJ is the source of pain and dysfunction |

| Pain localised to the TMJ |

| Pain on functional loading of the TMJ |

| Pain on movement of the TMJ |

| Mechanical interference with TMJ function |

| Specific indications |

| Disorder not responding to TMJ arthrocentesis or arthroscopy |

| Chronic severe limited mouth opening |

| Advanced degenerative joint disease with intolerable symptoms of pain and joint dysfunction |

| Confirmation of severe joint disease on CT scan or MRI |

Open surgery (arthrotomy) of the TMJ is undertaken for a wide range of joint disorders. In 1994, Dolwick and Dimitroulis [4] divided the indications for surgery into relative and absolute. As far as absolute indications are concerned, TMJ surgery has a definite undisputed role in the management of uncommon or rare joint disorders. TMJ ankylosis, whether fibrous or bony, is a classic example of a TMJ disorder where surgery has a pivotal role. Ankylosis has been the staple TMJ disorder in India for many years but is rare in Western nations. While TMJ ankylosis will always be a major concern for Indian oral and maxillofacial surgeons, improved access to health care may well reduce the incidence of this debilitating disease in the years to come. Other rare disorders, such as synovial chondromatosis, provide another example of the clear role that surgery has in removing the abnormal growths.

Unfortunately, the role of TMJ surgery in the management of common disorders such as traumatic injuries [9], internal derangement and osteoarthrosis is less clear and often ill-defined [3, 4]. These are considered under the heading of relative indications because non-surgical therapies appear to be equally effective in the management of these common disorders as surgical intervention. However, there are situations where the benefits of TMJ surgery are indisputable. These are further divided into general and specific indications. The most commonly cited general indication for TMJ surgery is where the joint disorder remains refractory, or not responding to non-surgical therapy, in particular, occlusal splints, medication and physiotherapy [2]. Some may argue that the failure of non-surgical therapy may well reflect the possibility of misdiagnosis, where surgical intervention should have been considered earlier on if the diagnosis was correctly made in the first place [3]. This is not to say that chronic pain syndromes should be ignored, since failed conservative therapy may well indicate a plethora of chronic pain conditions that require specialist pain management, which is a whole subject in its own right, and so will not be elaborated any further in this paper. Suffice to say that clinicians must be careful to differentiate between failed TMD cases that require chronic pain management and those that would benefit from a surgical opinion.

From a clinical standpoint, surgery is more likely to succeed if the source of the pain and dysfunction is well localised to the TMJ. Hence, pain specifically related to the TMJ, particularly when pain is elicited on direct palpation, loading of the joint and functional movements of the joint. Mechanical interferences arising from within the joint that limit its full functional potential, such as painful clicking, locking and crepitus, are all good indicators of likely surgical disorders. It must be emphasized that the more localised the symptoms are to the TMJ, the more likely surgery will have a favourable outcome.

Specific indications for TMJ surgery include chronic severe limited mouth opening and gross mechanical interferences such as painful clicking and crepitus that fail to respond to TMJ arthrocentesis and arthroscopy. Radiologically confirmed degenerative joint disease, with clinical features of intolerable pain and joint dysfunction, are essentially the key criteria for TMJ surgical intervention [4].

It must be stressed that where significant joint pathology has been identified, both clinically and radiologically, non-surgical therapies only treat the symptoms. In these situations, only surgical intervention can treat the disease [3]. Therefore, all TMD practitioners should be alert to the possibility that in select cases the only realistic option is TMJ surgery. Even though most clinical studies are based more on observation than sound scientific principles, the literature is unequivocal in its support for surgery in the management of certain TMJ disorders [7, 8].

Prior to the introduction of sophisticated imaging such as CT and MRI, surgeons were less discerning with their patients and considered joint surgery as part investigative and part therapeutic. This resulted in poor outcomes for some patients who had chronic neuromuscular pain conditions and normal TMJ’s that were subjected to surgical insults that failed to relieve their symptoms. In the light of past mishaps, contraindications to surgery have become intertwined with the adverse risks of TMJ surgery which is outlined in Table 2. It is, therefore, critical to point out that surgery has no role in the management of patients with chronic pain syndrome or muscular problems that do not involve the joint itself.

Table 2.

Risks and contraindications associated with TMJ surgery

| Poor patient selection |

| Patient is an unreliable historian |

| Secondary gain |

| Compensation seeking |

| Patient has unrealistic expectations of surgical outcome |

| Significant medical history |

| Psychiatric history |

| Inexperienced clinician |

| Poor diagnostic skills |

| Limited surgical experience |

| Bleeding |

| Infection and wound breakdown |

| Scarring |

| Surgical mishaps |

| Facial nerve paresis |

| Deafness |

| Malocclusion |

| Condylar resorption |

| Overzealous arthroplasty |

| Severe trismus (arthrogenous) |

| Adhesions |

| Fibrosis |

| Ankylosis |

| Persistent symptoms |

| Failure to continue supportive non-surgical therapy |

| Poor patient compliance—cannot follow instructions |

| Misdiagnosis—chronic pain syndrome, myofascial pain, normal joint |

Surgical Procedures to the TMJ

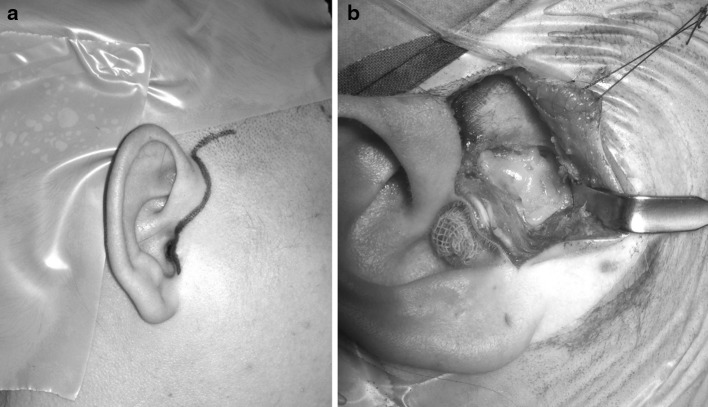

TMJ surgery is technically one of the more difficult surgical dissections in the maxillofacial region. While the close proximity of the facial nerve is the main reason for the difficult surgical access, other important anatomical structures such as the terminal branches of the external carotid artery and accompanying rich plexus of veins also add to the complexity of the dissection. With the middle cranial fossa above, and the middle ear behind the TMJ, there is little room for surgical error as both these cavities are only a few millimetres away from the joint itself. The most common approach used by the author is the endaural incision with temporal extension as shown in Fig. 1a, b.

Fig. 1.

a, b The endaural approach with temporal extension is shown in Fig. 1a. The joint is displayed with dermis-fat graft in situ in Fig. 1b. The endaural incision must be careful not to cut into the tragal cartilage. Dermis fat grafts are used by the author as the interpositional material of choice for TMJ ankylosis management

There are a myriad of surgical procedures which are undertaken to either restore, repair or remove damaged or diseased joint tissues [4, 5]. TMJ arthrocentesis and arthroscopy have proven to be the most effective way of managing ‘stuck’ joints by the simple process of lubricating the superior joint space and allowing mobilization of the articular disc [1, 10]. While TMJ arthrocentesis is useful for cases of acute onset closed lock [1], TMJ arthroscopy (Fig. 2) provides a more effective approach to the management of chronic (>3 months) or recalcitrant cases of closed lock [11]. Disc repair and repositioning has fallen out of favour in recent years as the results of these procedures have been somewhat equivocal [12]. Studies have shown that the surgical repositioning of displaced discs is often short lived as the discs have been found to revert to their displaced position when imaged postoperatively [12–15]. Furthermore, attempts to repair damaged or worn discs often result in failure due to the lack of a direct blood supply to the disc and the dynamic forces imparted on the disc during normal jaw function which prevents healing [12, 16]. The introduction of TMJ arthroscopy [17], and later arthrocentesis [18], further questioned the role of disc repositioning in the management of internal derangement that results in closed lock, as these lesser procedures are found to be effective in releasing stuck joints without the need to reposition the displaced disc [10, 19, 20].

Fig. 2.

The TMJ arthroscopy puncture points are placed after the position of the condyle and fossa are palpated and outlined with pen. This gives a better representation of the actual joint space than the McCain method of using the tragal-canthus line and measuring arbitrary distances

Others have discussed the role of removing obstructions to the free movement of the disc such as eminence reduction, or eminectomy, as a means of reducing the symptoms of internal derangement. Once again, the evidence for the efficacy of this procedure is lacking [4, 21]. The old idea of high condylar shaves to reduce the pressure on the disc has also been revived on a number of occasions but, once again, the long term data is also lacking [22].

One procedure which has become the mainstay in the treatment of severe TMJ internal derangement is the discectomy [23–25], or complete removal of the disc. Discectomy is one of the few TMJ surgical procedures which have >20 year follow-up data to show the long term effectiveness [26–30]. While TMJ discectomy has worked well, the problems encountered are mainly centred on the remodelling effects on the condyle which radiologically appears as osteoarthrosis [31–33]. Therefore, numerous attempts have been made over the years to replace the disc with either alloplastic or autogenous grafts but with little success. The disastrous experience of Teflon-proplast and sialastic implants as disc replacement materials [34, 35] has led to the concerted effort to find an autogenous graft that is both safe and effective in reducing condylar remodelling following discectomy [8, 36]. Ear cartilage has been shown to lead to fragmentation, fibrosis and ankylosis of the TMJ [37] while full thickness skin has the propensity to result in epidermoid cyst formation [38]. Pedicled temporalis muscle and fascia are still used today [39], but these also have limited functionality with the potential to exacerbate trismus when temporalis muscle is surgically breached [8]. The use of dermis graft from the lower abdomen has been reported with good results, although it has not been found to offer a protective barrier to condylar remodelling [40]. One autogenous graft that has shown some promise is the dermis-fat graft (Fig. 1b) from the lower abdomen which was first introduced by Dimitroulis [41] as an interpositional material for TMJ ankylosis, and more recently for use as a space filler following TMJ discectomy with good outcomes [8].

As yet there has been limited success by tissue engineering laboratories to fabricate a disc substitute using biological scaffolds impregnated with stem cells which are modulated by active biochemical agents to produce a new disc that can be used to replace a diseased or worn disc [42]. Even if the perfect disc substitute is successfully developed, the problem remains as to how to properly anchor the new disc to the surrounding tissues that would allow ideal disc-condyle relationship to be maintained during normal joint function.

TMJ Replacements

Where there is end-stage joint disease, tumour or severe trauma, and none of the components of the TMJ can be salvaged, then both disc and condyle must be resected. This leaves patients with the dual physical handicaps of lower facial asymmetry and malocclusion, unless the joint is reconstructed with either autogenous grafts or alloplastic joints.

Unlike other joints in the body, the TMJ has had a long history of joint replacement materials consisting largely of autogenous grafts, in particular, the costochondral rib graft which is easily harvested and fashioned into a new condyle and secured to the ramus of the mandible with wires or screws [36, 43]. While rib grafts have been useful in young patients, older patients are not appropriate for rib graft replacements because of the brittle nature of the rib which increases the likelihood of fracture and also ankylosis when the cartilaginous cap is placed hard up against the glenoid fossa.

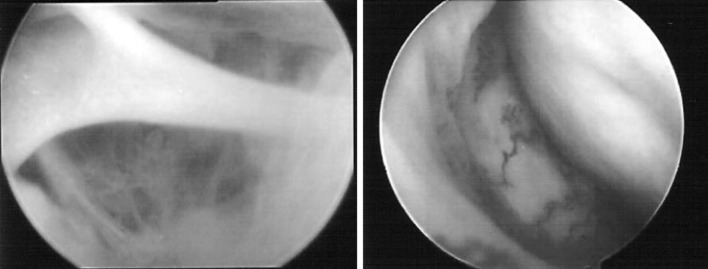

In older patients, the most appropriate joint replacement for the TMJ is the alloplastic prosthesis consisting of a metal condyle articulating against a high molecular weight polymer fossa prosthesis (Fig. 3a, b). Hemi-prosthetic joints consisting of a prosthetic fossa alone have been well described and appear to work well [44]. However, the use of prosthetic metal condyles against a natural bony fossa cannot be recommended as they result in erosion of the skull base unless it is protected by a prosthetic fossa. Early prosthetic joint replacements met with little success but more recent prosthetic joints, including both off the shelf varieties as well as custom made prostheses, have benefited from the technological advances and extensive experience of our orthopaedic colleagues [45, 46].

Fig. 3.

a Orthopantomogram with a metal prosthetic joint (condyle) secured to the mandibular ramus with 4 screws. The metal condyle articulates against a prosthetic fossa made of ultra-high molecular weight polymer. Only the screw fixation can be seen in the fossa. Figure 3b shows a lateral cephalogram view of the same TMJ prosthesis in the same patient. (Biomet—Lorenz TMJ prosthesis—Jacksonville Fl., is shown)

To help illustrate the role of TMJ surgery, 3 clinical cases treated by the author will be described below.

Case 1

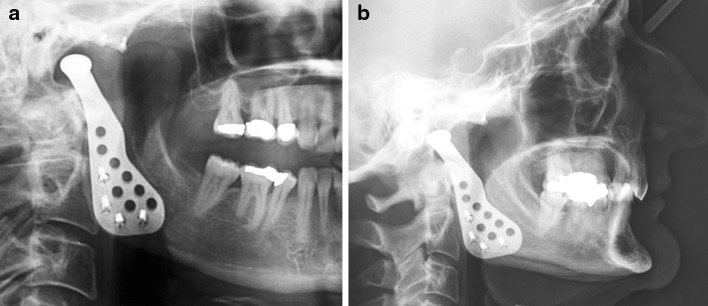

A 26 year female was referred to the author for management of a 6 month history of chronic closed lock. She had a long-standing history of painful clicking in the right TMJ that was successfully managed with occlusal splint therapy until 1 day she woke up with limited mouth opening that failed to respond to subsequent physiotherapy, antiinflammatories and ongoing splint therapy. Her maximum interincisal opening was reduced to 20 mm with gross deviation of the mandible to the right side on opening, which indicated the lack of translation of the right mandibular condyle. Radiological investigations (including MRI) showed non-reducing disc displacement in the right TMJ. The patient underwent right TMJ arthroscopy which highlighted the presence of inflammation of the synovial capsule as well as adhesions (Fig. 4) which were arthroscopically treated by lavage and lysis of adhesions with injection of steroids. The disc was arthroscopically released and mobilised and by the end of the procedure 38 mm of interincisal opening was achieved. Post-operatively, the patient was able to achieve 42 mm within 3 weeks of the procedure with reduced clicking in the right TMJ. By 6 weeks her pain levels had significantly diminished, but she was advised to return to using her occlusal splint because of her bruxism and clenching.

Fig. 4.

Arthroscopic pictures of the right TMJ from the patient described in case 1. The left picture shows a thick fibrous band of adhesion that was surgically excised. The right shows intense inflammation of the synovial lining of the medial capsule with the disc shown in the upper right side of the picture

Case 2

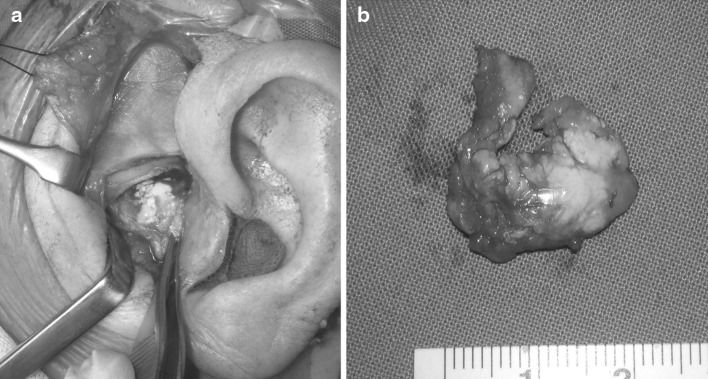

A 63 year lady was referred to the author for management of a constant dull pain in the left TMJ that had progressively become worse over the previous 12 months despite 18 months of occlusal splint therapy by her dentist and 6 months of low-dose tricyclic medication by her medical practitioner. She was referred to an Oral Medicine specialist who immediately ordered radiological investigations which demonstrated calcified bodies within the articular disc of the left TMJ. Fortunately, the surrounding condyle, glenoid fossa and articular eminence were unaffected. The patient underwent left TMJ surgery through a preauricular incision where the disc was found to be peppered with calcified firm lumps (Fig. 5a) and so was completely excised. As part of the reconstruction, the resultant joint cavity was filled with an abdominal dermis-fat graft to prevent hematoma, scarring and possible ankylosis formation within the joint. The disc specimen (Fig. 5b) was sent for histopathology which was reported as pseudogout, a rare condition mainly found in the fingers and toes. The patient remained in hospital overnight and was fully recovered within 2 weeks of her procedure. She was back to a normal diet in 6 weeks with smooth, pain free function in the left TMJ. She was last reviewed 4 years following her surgery with no clinical or radiological evidence of recurrence of the lesion, and continued to enjoy full range of pain-free function in the left TMJ.

Fig. 5.

a The intra-operative photo of the patient described in case 2 showing the calcified tissue from the left TMJ. The specimen that was removed, shown in Fig. 5b, was histologically diagnosed as pseudogout. While such intra-articular pathology is rare, the patient was managed with splint therapy and medications for over 18 months before she sought a surgical opinion

Case 3

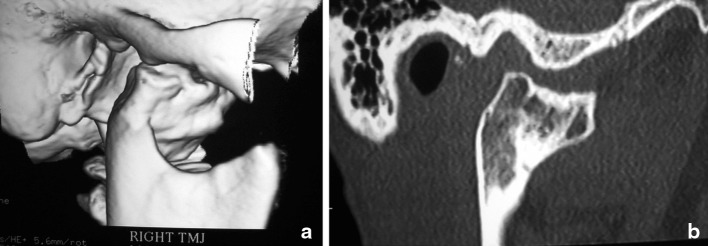

A 46 year female was referred to the author for surgical management of severe osteoarthritis affecting the right TMJ that had become painfully intolerable over the previous 6 months. She had fallen off a horse 10 years earlier and sustained a right intracapsular condylar fracture that was managed conservatively. The posttraumatic osteoarthritis was clearly visible on routine OPG and CT scans which showed severe deformation of the right mandibular condyle (Fig. 6). Arthroscopic biopsy of the right TMJ was undertaken to exclude the possibility of neoplasia. The patient was taken to theatre where she had the right TMJ resected and a total prosthetic joint replacement was undertaken to restore the missing joint components. The histopathology confirmed severe osteoarthrosis with significant degeneration of the right mandibular condyle and articular disc. Her 4 nights in hospital were uneventful and she was back to normal diet in 6 weeks. At her 1 year review, she reported no joint pain with an interincisal opening of 36 mm and was enjoying a normal dietary range. Apart from 3 months of physiotherapy, no further TMD therapy was required post-operatively.

Fig. 6.

a The three dimensional CT scan of the patient described in case 3 clearly demonstrating destructive degeneration of the right TMJ which turned out to be severe posttraumatic osteoarthrosis. Figure 6b demonstrates a CT sagittal slice of the affected right condyle. The right TMJ was surgically resected and a right TMJ total joint replacement was undertaken to restore joint function and maintain the occlusion and facial symmetry

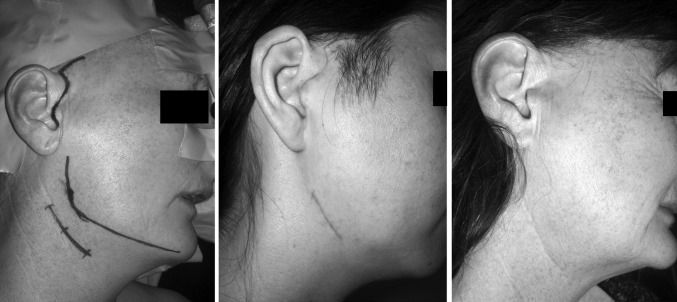

Risks Versus Benefits of TMJ Surgery (Table 2)

While the classically cited risks for TMJ surgery are facial nerve palsy and scarring (Fig. 7) there are, infact, many potential risks that are not so obvious to non-surgical practitioners such as malocclusion, restricted mouth opening and deafness [47] (Table 2). An inexperienced surgeon who seldom ventures into the TMJ is more likely to encounter problems through poor diagnostic skills which may result in poor patient selection and suboptimal surgical technique that does more harm than good for the patient. Fortunately, in experienced hands, most complications associated with TMJ surgery are of a temporary nature and account for <5 % of all procedures [4, 5].

Fig. 7.

Surgical approaches used for TMJ total joint replacements. The left hand picture shows the preauricular and retro-submandibular incisions. The middle picture shows the incision scars 10 days after surgery and the right hand picture shows the barely visible scars 1 year following surgery

The benefits of TMJ surgery can only be realised by appropriate case selection which is supported by an accurate diagnosis. An experienced surgeon with good patient skills will be able to identify patients who are compliant with treatment regimes, have a good understanding of their disorder, and do not harbor unrealistic expectations for treatment outcomes. On the other hand, an inexperienced surgeon with poor patient skills will be tempted to operate on patients who have a poor understanding of their disorder, a long history of poor compliance with treatment, and unrealistic expectations. In these situations the risks of surgery would far outweigh the benefits.

A multidisciplinary team approach to TMD management, especially where surgery is involved, is essential in the fundamental care of all TMD patients. Surgeons who work in isolation run the risk of overlooking serious issues that may adversely impact on the long term care and well being of the patient. Therefore, it is important that input from all members of the specialist team is carefully considered so that a balanced judgement can be made as to whether the patient in question is an appropriate candidate for TMJ surgery. And most importantly, a decision has to be made as to whether the benefits of TMJ surgery far outweigh the inherent risks.

The Future of TMJ Surgery

The future holds great promise for TMJ surgery, which is reflected in the dominance of orthopaedic surgery that largely treats disorders and diseases of many other joints in the body. It is no coincidence that orthopaedic surgery is the largest and busiest of all surgical specialties worldwide and much can be learned from their vast experience of surgery to the knee, hip and shoulder joints.

While India boasts the largest collective experience in the surgical management of TMJ ankylosis, times are changing and Indian surgeons will need to begin thinking about other TMJ disorders that have previously gone under the radar. A growing Indian middle class with greater access to health facilities will demand treatment for TMJ disorders like myofascial pain and dysfunction, internal derangement and osteoarthrosis which Oral & Maxillofacial Surgeons must be prepared to manage. There will be diagnostic challenges that must be confronted because the role of surgery is not as clear cut for other TMJ disorders as they are for TMJ ankylosis. The 21st century will bring big changes to India, and as the nation prospers, the kind of patient that presents to the Oral & Maxillofacial Surgeon will be very different. Therefore, all surgeons must be prepared for changes that will come sooner than later.

References

- 1.Al-Belasy FA, Dolwick MF. Arthrocentesis for the treatment of temporomandibular joint closed lock. A review article. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;36:773–782. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dimitroulis G. Temporomandibular disorders: a clinical update. Br Med J. 1998;317:190–194. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7152.190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dimitroulis G. The role of surgery in the management of disorders of the temporomandibular joint: a critical review of the literature; Part 1. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;34:107–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2004.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dolwick MF, Dimitroulis G. Is there a role for temporomandibular joint surgery? Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1994;32:307–313. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(94)90052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dolwick MF, Sanders B. TMJ internal derangement and arthrosis—surgical atlas. St. Louis: CV Mosby Co; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Larheim TA. Role of magnetic resonance imaging in the clinical diagnosis of the temporomandibular joint. Cells Tissues Organs. 2005;180:6–21. doi: 10.1159/000086194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reston JT, Turkelson CM. Meta-analysis of surgical treatments for temporomandibular articular disorders. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61:3–10. doi: 10.1053/joms.2003.50000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dimitroulis G. The role of surgery in the management of disorders of the temporomandibular joint: a critical review of the literature; Part 2. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;34:231–273. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dimitroulis G. Condylar injuries in growing patients. Aust Dent J. 1997;42:367–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.1997.tb06079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holmlund AB, Gynther GW, Axelsson S. Efficacy of arthroscopic lysis and lavage in patients with chronic locking of the temporomandibular joint. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1994;23:262–265. doi: 10.1016/S0901-5027(05)80104-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dimitroulis G. A review of 56 cases of chronic closed lock treated with temporomandibular joint arthroscopy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;60:519–524. doi: 10.1053/joms.2002.31848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dolwick MF. Disc preservation surgery for the treatment of internal derangements of the temporomandibular joints. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;59:1047–1050. doi: 10.1053/joms.2001.26681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conway WF, Hayes CW, Campbell RL, Laskin DM, Swanson KS. Temporomandibular joint after meniscoplasty: appearance at MR imaging. Radiology. 1991;180:749–753. doi: 10.1148/radiology.180.3.1871289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaplan PA, Reiskin A, TU H. Temporomandibular joint arthrography following surgical treatment of internal derangement. Radiology. 1987;163:217. doi: 10.1148/radiology.163.1.3823438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Montgomery MT, Gordon SM, Sickels JE, Harms ST. Changes in signs and symptoms following temporomandibular joint disc repositioning surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1992;50:320–328. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(92)90389-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bosanquet AG, Ishimaru J, Goss AN. Effect of fascia repair of the temporomandibular disk of sheep. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1991;72:520–523. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(91)90486-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohnishi M. Arthroscopy of the temporomandibular joint (Jap) J Jpn Stomat. 1975;42:207–212. doi: 10.5357/koubyou.42.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nitzan DW, Dolwick MF, Martinez GA. Temporomandibular joint arthrocentesis: a simplified treatment for severe, limited mouth opening. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991;49:1163–1167. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(91)90409-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dolwick MF, Dimitroulis G. A re-evaluation of the importance of disc position in temporomandibular disorders. Aust Dent J. 1996;41:184–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.1996.tb04853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nitzan DW, Samson B, Better H. Long-term outcome of arthrocentesis for sudden-onset, persistent, severe closed lock of the temporomandibular joint. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1997;55:151–157. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(97)90233-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Revington PJD. The Dautrey procedure—a case for reassessment. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1986;24:217–220. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(86)90078-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henny FA, Baldridge OL. Condylectomy for the persistently painful temporomandibular joint. J Oral Surg. 1957;15:24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holmlund AB, Gynther GW, Axelsson S. Diskectomy in treatment of internal derangement of the temporomandibular joint. Follow-up at 1, 3 and 5 years. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1993;76:266–271. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(93)90250-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McKenna SJ. Discectomy for the treatment of internal derangements of the temporomandibular joint. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;59:1051–1056. doi: 10.1053/joms.2001.26682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nyberg J, Adell R, Svensson B. Temporomandibular joint diskectomy for treatment of unilateral internal derangements—a 5 year follow-up evaluation. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;33:8–12. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2002.0453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eriksson L, Westesson P-L. Long-term evaluation of menisectomy of the temporomandibular joint. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1985;43:263–269. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(85)90284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hansson LG, Eriksson L, Westesson P-L. Magnetic resonance evaluation after temporomandibular joint diskectomy. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1992;74:801–810. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(92)90413-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Silver CML. Long-term results of menisectomy of the temporomandibular joint. J Craniomandib Pract. 1984;3:46–49. doi: 10.1080/08869634.1984.11678085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takaku S, Toyoda T. Long-term evaluation of discectomy of the temporomandibular joint. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1994;52:722–726. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(94)90486-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tolvanen M, Oikarinen VJ, Wolf J. A 30 year follow-up study of temporomandibular joint menisectomies: a report of 5 patients. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1988;26:311–313. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(88)90049-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Agerberg G, Lundberg M. Changes in the temporomandibular joint after surgical treatment. A radiological follow-up study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1971;32:865–875. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(71)90171-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ericksson L, Westersson P-L. Temporomandibular joint discectomy. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1992;74:259–272. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(92)90056-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hinton RJ. Alteration in rat condylar cartilage following discectomy. J Dent Res. 1992;71:1292–1295. doi: 10.1177/00220345920710060501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaplan PA, Tu HK, Williams SM. Erosive arthritis of the temporomandibular joint caused by Teflon-Proplast implants: plain film features. Am J Roentgenol. 1988;151:337–340. doi: 10.2214/ajr.151.2.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Westesson P-L, Eriksson L, Lindstrom C. Destructive lesions of the mandibular condyle following diskectomy with temporary silicone implant. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1989;47:1290–1293. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(89)90545-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.MacIntosh RB. The use of autogenous tissues for temporomandibular joint reconstruction. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000;58:63–69. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(00)80019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dimitroulis G, Lee D-K, Dolwick MF. Autogenous ear cartilage grafts for treatment of advanced temporomandibular joint disease. Ann R Australas Coll Dent Surg. 2004;17:87–92. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dimitroulis G, Slavin J. Histological evaluation of full thickness skin as an interpositional graft in the rabbit craniomandibular joint. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;64:1075–1080. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feinberg SE. Use of composite temporalis muscle flaps for disc replacement. Oral Maxillofac Clin N Am. 1994;6:335–337. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dimitroulis G. The use of dermis grafts after discectomy for internal derangement of the temporomandibular joint. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63:173–178. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2004.06.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dimitroulis G. The interpositional dermis-fat graft in the management of temporomandibular joint ankylosis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;33:755–760. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2004.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Allen KD, Athanasiou KA. Tissue engineering of the TMJ disc: a review. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:1183–1196. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Politis C, Fossion E, Bossuyt M. The use of costochondral grafts in arthroplasty of the temporomandibular joint. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1987;15:345–354. doi: 10.1016/S1010-5182(87)80081-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baltalti E, Keller EE. Surgical management of advanced osteoarthritis of the temporomandibular joint with metal fossa-eminence hemijoint replacement: 10 year prospective study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66:1847–1855. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mercuri LG. Alloplastic temporomandibular joint reconstruction. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1998;85:631. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(98)90028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mercuri LG. The use of alloplastic prostheses for temporomandibular joint reconstruction. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000;58:70–75. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(00)80020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vallerand WP, Dolwick MF. Complications of temporomandibular joint surgery. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin N Am. 1990;2:481–488. [Google Scholar]