Abstract

Cystic hygroma or cystic lymphangioma is a congenital malformation of the lymphatic system that manifests itself as a soft, benign, and painless mass. It is widely accepted that they arise from the remnants of embryonic lymphatic tissue which retains the potential for proliferation. They grow in the fashion of sprouting and are capable of transgressing anatomical boundaries. They can occur almost at any anatomical site. However, 75–80% cystic hygromas are located in the head and neck region. In the neck, they are typically located within the posterior cervical triangle. The majority of cases (80–90%) are diagnosed under the age of two. We present a case of cervical cystic hygroma in a 6 year old male child which was surgically treated.

Keywords: Cystic hygroma, Cystic lymphangioma

Introduction

Hygroma cysticum coli or cystic hygroma is a division of lymphangiomas that presents mostly at birth, it is therefore a congenital malformation of the lymphatic system [1, 2]. Most of these tumors are identified by the time the patient reaches the age of 3 to 5 years [2]. The most common site for the tumor is the posterior triangle of the neck and it may involve vital structures, such as the sympathetic chain, carotid sheath content, and branches of the hypoglossal, lingual, and the facial nerves [2]. Depending on the anatomical site, cystic hygroma may cause dysphagia or airway obstruction and respiratory distress that necessitates immediate surgical interference [3–5]. The cystic hygroma in the neck is manifested as large, deep, diffuse swelling [1, 5]. On palpation, it is, often doughy and is usually transilluminant. These lesions are composed of lymph containing endothelial spaces that vary in size from capillary dimensions to cysts of several centimeters in diameter [6]. Although, the embryologic origin is still unclear, failure of primary lymph spaces to join the central lymphatic system (thoracic duct and right lymphatic duct) and the venous system may be the basis for their development. Cystic hygroma is usually multiloculated and is composed of spaces.

These spaces contain straw colored fluid which may be discolored with secondary infection of intracystic hemorrhage [7]. It may also cause obstructive sleep apnea. Such apnea is a different sign of presentation than the ones that are commonly observed. Commonly, the hygroma manifests itself as a uni or bilateral swelling of the neck that causes asymmetry [8]. Although surgical excision of the tumor, is the treatment of choice for most clinicians, local injection of bleomycin fat emulsion could be another successful alternative [9]. In this report, we are presenting a case of cervical cystic hygroma in a 6 year old male child which was treated surgically.

Case Report

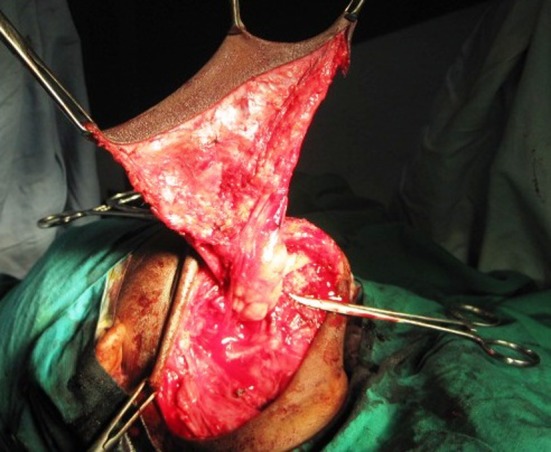

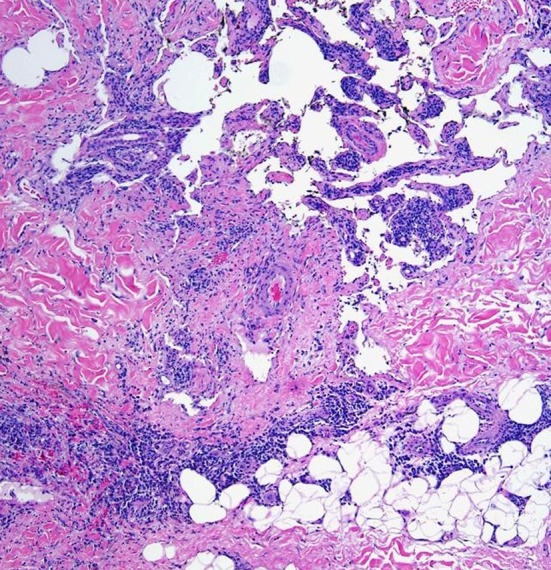

A 6 year old male patient was referred to the department of oral and maxillofacial surgery with a chief complaint of large swelling on the right side of the jaw for past 2 years. Examination of the patient revealed soft, diffuse, mobile large swelling over the submandibular region (Fig. 1a, b). Swelling was small in size initially which gradually increased in size. The swelling was 12×8 cm in size non-tender, mobile, non-pulsatile, cystic in consistency, non-compressible and fluctulant. Transillumination test was positive and aspiration of the lesion resulted in brownish fluid. Clinical diagnosis of cystic hygroma was made. CT scan showed the extent of the tumor and showed large cystic lesion with definite boundaries (Fig. 2). The patient was then admitted for surgical removal of the lesion under general anesthesia. Through a submandibular incision, the lesion was completely excised (Figs. 3, 4). The facial nerve branches were identified and preserved. Careful dissection of the lesion anteriorly up to the midline, superiorly up to the lower border of the mandible, and posteriorly up to the tail of the parotid was carried out. The masses were separated from their attachment to sternocleidomastoid muscle. Hemostasis was achieved using cautery and ligation. Wound closure was done, by suturing the subcutaneous tissue followed by fascia and skin. The patient was hospitalized for 3 days and was discharged in a satisfactory condition (Fig. 5). There was no facial nerve deficit and patient is under regular follow up. The surgical specimen measured 7 × 5 cm, appeared irregular in shape but was well circumscribed. Cut surface revealed multiple cyst like spaces separated by thin fibrous septae and filled with gelatinous material and few cystic spaces filled with blood (Fig. 4). Histopathology revealed varying proportions of large and small lymphatic channels containing lymph, few blood vessels, adipose tissue, fibrous tissue, and lymphoid tissue. Areas of haemorrhage were also seen (Fig. 6). Based on the microscopic observations in correlation with clinical features, a final diagnosis of cystic hygroma was made.

Fig. 1.

a Photograph showing diffuse swelling over right submandibular region causing severe facial asymmetry. b Photograph showing the size and the extent of the tumor

Fig. 2.

CT scan axial view showing the cystic lesion and its boundaries

Fig. 3.

Photograph showing the submandibular incision and the tumor uncovered with flap reflected

Fig. 4.

Complete excision of the tumor. Surgical specimen showing multiple cyst like spaces separated by thin fibrous septae

Fig. 5.

4 weeks post-operative photograph showing complete recovery on the right side of the face

Fig. 6.

Multiple lymphatic channels containing few blood vessels, adipose tissue, and fibrous tissue (H and E, ×40)

Discussion

Cystic hygromas are relatively rare lesions approximately 65–75% of them are present at birth and 80–90% are identified by age of 3 years [4, 5] and very rarely seen during adulthood. In head and neck cervical area is the predominant site for occurrence particularly the posterior triangle (75–80%), due to presence of extensive lymphatic system. Due to infiltrative nature of hygromas within the soft tissues of the neck, these may extend from posterior cervical area into the anterior compartment of neck, may cross the midline, may reach into the cheek or down into the mediastinum and axilla. In general, symptoms vary from one mere presence of a painless, enlarging mass to respiratory compromise, dysphagia and difficulty in feeding with regurgitation [4, 5]. Very rarely, massive hygroma may present with symptoms of neural encroachment (brachial plexuses and recurrent laryngeal nerve). Cystic hygroma vary from 1–30 cm in size, the mean size in Stromberg’s series was 8.0 cm [4].The treatment of cervical hygromas has varied from benign neglect to complete excision. Surgical advocates [3, 4], claim that these tumors may grow relentlessly, producing unacceptable cosmetic distortion of the face and neck, may compromise trachea and brachial plexus. The infiltrative hygromas as more risky while operating with the potential for incomplete excision, surgical sequel of neural injury, persistent lymphoedema, lymphocele and lymphorrhoea as being worse than the presence of the tumor itself. The use of sclerosing agents has no role in the cure of hygromas. Aspiration of hygromas is useful only to decompress, when they are compromising the airways. Lymphangiomas being radioresistant, the radiation therapy is avoided for its ineffectiveness and potential for delayed carcinogenesis [1, 4, 5]. Surgical therapy, with wide excision as possible preserving cosmetic function, is the best approach to these lesions [6]. Contrast-enhanced CT and MRI are valuable in the differential diagnosis, and are also helpful in planning surgery by displaying the relation of the mass with neighboring structures. In this respect, T2-weighted MRI is superior to CT especially for visualizing skull base extension, as it is not hindered by bony artifacts. Nonsurgical management of CHC has been advocated by some authors in order to avoid tedious and risky task of surgical resection. Kennedy et al. [10]. recommended awaiting spontaneous resolution in order to avoid potential hazards of surgery. Radiotherapy (RT) which was used in the past has now been almost abandoned due to the risk of malignant transformation of the lesion. Sclerotherapy with bleomycin and OK-432 have been used in the treatment of cystic hygroma with some success, especially in children. Sclerosing agents such as boiling water, sodium morrhuate, alcohol, and 50% dextrose are also used, but the disadvantages of these agents are their unpredictable results and extensive sclerosis, which may make future surgery extremely difficult when it is required [11, 12]. Especially in children, nonsurgical treatment options are suggested for lesions located over the parotid region in order to avoid the complications of surgery. [13] Therefore, surgical excision still remains as the treatment of choice. Staged excision may be necessary to avoid mutilating surgical procedure in some selected cases. The objective in surgery of cystic hygroma is relief of obstruction upon vital structures and a good cosmetic result, good judgement must control the extent of the operation. Inadequate operation is just as inexcusable. Therefore, cystic hygroma are benign tumors of lymphatic system, manifesting mainly in early childhood and are best treated surgically with conservative approach.

Conclusion

Surgical excision is the treatment of choice for cystic hygromas. Cystic hygroma in the orofacial region is a difficult lesion to excise. Although the tumor is benign, the intimate relation to the various important anatomic structures makes its dissection a tedious task. Involvement of the skin makes it a risk during raising the skin flap and even after successful elevation, the sensibility of the skin is jeopardized which may be dangerous if the patient is instructed to apply hot compresses. Extension of the lesion and involvement of muscle and glandular structure make complete excision sometimes impossible. When complete excision is sought, unnecessary sacrifice of muscles will leave the patient with a deformity which is more difficult to treat as it constitutes a deformity in the form of a defect and a functional one in the form of loss of muscle function. Partial excision may be the solution, even though recurrence is possible following incomplete excision. The goal in the management of cystic hygromas must be primarily to relieve obstruction upon vital tissues and a good cosmetic result.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- 1.Shafer WG, et al. A textbook of oral pathology. 4. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders Co; 1983. pp. 159–160. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aantoniades K, Kiziridou A, Psimopoulou M. Traumatic cervical cystic hygroma. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000;29(1):47–48. doi: 10.1016/S0901-5027(00)80124-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hamoir M, Renacle M, Youssif A, Moulin D, et al. Surgical management of peri-pharyngeal cystic hygroma causing sudden airway obstruction. Head Neck Surg. 1988;10(6):406–410. doi: 10.1002/hed.2890100608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crosfeld JT, Weber TR, Vane DW. One-stage resection for massive cervico-mediastinal hygroma. Surgery. 1982;92(4):693–699. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barnhart RA, Brown AK., Jr Cystic hygroma of the neck. Arch Otolaryngol. 1967;86(1):74–78. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1967.00760050076016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bill AH, Summer DS. A unified concept of lymphangioma and cystic hygroma. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1965;120:79–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Toranzo Jose M, Guerrero F, Dibidox J, Gonzalez G, Sedano HO. A congenital neck mass. Oral Surg Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1996;82:363–364. doi: 10.1016/S1079-2104(96)80298-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kahn A, Blum D, Hoffman A, Moulin D, Spehl M, Montauk L. Obstructive sleep apnea induced by parapharyngeal cystic hygroma in an infant. Sleep. 1985;8(4):363–366. doi: 10.1093/sleep/8.4.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanigawa N, Shimomatsuya T, Takahashi K, Inomata Y. Treatment of cystic hygroma and lymphangioma with the use of bleomycin fat emulsion. Cancer. 1987;60(4):741–749. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19870815)60:4<741::AID-CNCR2820600406>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kennedy TL, Whitaker M, Pellitteri P, Wood WE (2001) Cystic hygroma/lymphangioma: a rational approach to management. Laryngoscope 111(11 pt 1):1929–1937 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Molitch HI, Unger EC, Witte CL, van Sonnenberg E. Percutaneous sclerotherapy of lymphangiomas. Radiology. 1995;194(2):343–347. doi: 10.1148/radiology.194.2.7529933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katsuno S, Ezawa S, Minemura T. Excision of cervical cystic lymphangioma using injection of hydrocolloid dental impression material. A technical case report. IntJ Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999;28(4):295–296. doi: 10.1016/S0901-5027(99)80162-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ikarashi T, Inamura K, Kimura Y. Cystic lymphangiomas and plunging ranula treated by OK-432 therapy: a report of two cases. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 1994;511:196–199. doi: 10.3109/00016489409128331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]