Abstract

The built environment has been implicated in the development of the epidemic of obesity. We investigated the differences in the meal patterns of normal weight vs. overweight/obese individuals occurring at home vs. other locations. The location of meals and their size in free-living participants were continuously recorded for 7 consecutive days. Study 1: 81 males and 84 females recorded their intake in 7-d diet diaries and wore a belt that contained a GPS Logger to record their location continuously for 7 consecutive days. Study 2: 388 males and 621 females recorded their intake in diet diaries for 7 consecutive days. In both studies, compared to eating at home, overweight/obese participants ate larger meals away from home in both restaurants and other locations than normal weight participants. Overweight/obese individuals appear to be more responsive to environmental cues for eating away from home. This suggests that the influence of the built environment on the intake of overweight/obese individuals may contribute to the obesity epidemic.

Keywords: Eating, Meal size, GPS, GIS, Body weight, obesity, built environment

Introduction

The General Model of Intake Regulation (de Castro & Plunkett, 2002) suggests that as long as the environment and physiology are stable, body weight will be maintained at a stable settling point. A new stable body weight will only be attained if a long-term change in either the environment or the physiology occurs. Over the last several decades there has been a marked increase in the body weight of the population producing what has been referred to as the epidemic of obesity (Wang & Beydoun, 2007; Wang, Beydoun, Liang, Caballero, & Kumanyika, 2008). In parallel there have been a large number of changes in the environment including changes in the physical, socio-cultural, dietary, and built environments. That these environmental changes parallel the rise in the incidence of obesity is suggestive of a possible causal connection (Trasande, Cronk, Durkin, Weiss, Schoeller, Gall, Hewitt, Carrel, Landrigan, & Gillman, 2009; Kirk, Penney, & McHugh, 2010).

Many of the recent environmental changes result from man made structural changes in the environment. These built environment changes have been receiving increasing scrutiny as potential contributory factors (Sallis & Glanz, 2009). The vast majority of the published studies find links between obesity and the built environment (Holsten, 2009; Papas, Alberg, Ewing, Helzlsouer, Gary, & Klassen, 2007). One of the recent environmental changes has been a rapid growth in the availability of food in the immediate environment which has been linked to overweight and obesity(Bezerra & Sichieri, 2009; Cohen, 2008; Duffey, Gordon-Larsen, Jacobs, Williams, & Popkin, 2007; Schröder, Fïto, & Covas, 2007; Li, Harmer, Cardinal, Bosworth, Johnson-Shelton, Moore, Acock, & Vongjaturapat, 2009). Indeed, obesity appears to be associated with the density of all restaurants (Inagami, Cohen, Brown, & Asch, 2009) and convenience stores (Galvez, Hong, Choi, Liao, Godbold, & Brenner, 2009) in the immediate neighborhood.

It would be difficult to account for the obesity epidemic based solely upon environment since not everyone has become obese. The General Model of Intake Regulation (de Castro & Plunkett, 2002) accounts for this by postulating that individuals inherit different susceptibilities to environmental influences, such that some individuals will react to a given environment by overeating while others who did not inherit susceptibility will not. In addition, the changes that have occurred in the built environment would be expected to have their maximum effect outside of the home. This suggests that if the built environment is at least in part responsible for the obesity epidemic then susceptible individuals should overeat outside of the home. To look at this issue, we investigated whether overweight individuals eat differently at home and away from home than normal weight individuals.

There is a weakness in prior studies in that they, in general, attempt to ascribe the individual’s overall behavior to the characteristics of a single environment, that surrounding the individual’s home. But, a large proportion of an individual’s behavior occurs away from home. To properly assess environmental impacts, then, it is important to be able to determine the exact location where the behavior occurs and the characteristics of these immediate environments. The development of portable GPS and GIS technologies has made it possible to objectively document the exact environments and their characteristics where the behaviors of freely living humans occur. In the present study eating was recorded by the participants in 7-day diet diaries and GPS was employed to record the exact location of free-living participants at the time they were eating in their normal everyday environments.

STUDY 1

Methods

Participants

The data were collected from 165 individuals consisting of 81 males and 84 females from El Paso, Texas. They were recruited via advertisements and referrals. The participants were paid $100 to participate and also received a detailed nutritional analysis of their intake. The male and female participants had a mean +/− standard error age of 26.3 +/− 0.8 and 29.4 +/− 1.2 years respectively, weights of 84.3 +/1 2.4 kg and 68.6 +/− 1.4 kg respectively, heights of 1.73 +/− 0.01 m and 1.60 +/− 0.01 m respectively, and had mean body mass indexes of 28.0 +/− 0.8 and 27.0 +/− 0.6 kg/m2 respectively. Participants were identified as normal weight if their BMI was less than 25 kg/m2 (n=60) and overweight/obese if their BMI was 25 kg/m2 or higher (n=105). In order to participate, the individuals could not be actively dieting, pregnant or lactating, on chronic medication, or alcoholic as ascertained with a demographic questionnaire. The study was approved by The University of Texas at El Paso Institutional Review Board.

Equipment

GPS measurement was performed with a GeoLogger (GeoStats, Atlanta, Ga) for 32 participants, while a lighter version GlobalSat Data Logger (US Globalsat, Inc., Chino, CA) was employed for 133 participants. Dietary intake was recorded in a small (8 × 18 cm) pocket sized diary. In addition, participants photographed their foods with a Largan Chameleon Mega (Largan Inc., Phoenix, AZ) digital camera. All equipment was contained in a specially constructed belt that was worn around the waist.

Procedure

Participants came to the laboratory for instruction and measurement on three occasions. At their initial visit they signed an informed consent form, completed an extensive demographic questionnaire, and were measured for height and weight. They were then issued their equipment and belts and instructed on their care and use. Participants were instructed to wear the belts at all times except for during sleep or bathing.

The participants were instructed to record their intake in the diaries in as detailed a manner as possible, every item that they either ate or drank, the time they ate it, the amount they consumed, how the food was prepared, and the number of other people eating with them. They also recorded where they ate the meal and the nature of their eating companions, e.g. family, friends, work associates etc. Self-ratings were obtained of the participants’ degree of hunger on 7-point Likert scales at the beginning and end of every meal. In addition, they took a picture of their food prior to and after the meal. For a detailed review of the method, reliability, and validity of the diet-diary procedure see de Castro (1994, 1999a).

The participants initially wore their belts and recorded their dietary information for one practice day. They then returned for their second laboratory visit. The dietary records and pictures were then reviewed. The proper functioning of the GPS recorder was verified. Any problems noted resulted in remedial instruction. Data obtained during this practice day was not used in any further analysis.

The participants then recorded their intake for seven consecutive days. Afterwards they returned to the laboratory where their records were inspected and the participants queried regarding any ambiguities or missing data. If the records were maintained properly and the data recorded for the week by the GPS recorder, the participants were paid and thanked for their participation. If there were significant gaps in the records or recordings, the participants were requested to record their intake and wear the belts for another week.

Data Analysis

Participants were separated into normal weight (BMI < 25 kg/m2) and overweight/obese (BMI >=25 kg/m2) groups. Comparisons were performed within subjects, which is the most appropriate and valid method for analyzing self-report data (de Castro, 2006). The data were then analyzed with ANOVA for mixed designs.

Food and Fluid Daily and Meal Intake

The foods reported in the diaries were assigned codes by an experienced dietitian from a computer file containing the nutrient compositions of common food items created from the U.S. Department of Agriculture Handbooks No. 8 and 456 of the Nutritive Value of American Foods. In addition, food composition of Mexican foods was obtained from the nutrition software (NUTRIKAL, Mexico City). The data base was supplemented with information obtained from package labels, from personal communications with food industry sources, and from current published literature. The coder was unaware of the experimental hypotheses or the participants’ characteristics and did not interact directly with the participants.

Meals were identified and the food energy (kJ) and nutrient compositions of the individual items composing the meal were summed. Meals were defined based upon the amount eaten (minimum of 209 kJ) and the time from the preceding and following intakes (before and after meal intervals, minimum 45 min.). The meals were characterized by their total energy content, carbohydrate, fat, protein, and alcohol content, duration of the meal, and the rate of intake (kJ / min), and the before and after meal ratings of hunger. The contents of the stomach at the beginning and end of the meals were estimated from the 7-day diary records with a computer model of stomach emptying. The reported intake was estimated to empty from the stomach at a rate proportional to the square root of the energy content of the stomach, Sn+1 = Sn − 5√Sn where S equals the stomach content in calories and n equals a particular minute of the day. This procedure reflects actual measured emptying rates from the human stomach (Hopkins, 1966; Hunt & Knox, 1968; Hunt & Stubbs, 1975) and has been used in prior studies (Booth, 1988; de Castro, 1987a; 1999b; 2005).

To measure the level of self-reported energy intake (EI) relative to the participant’s estimated requirements, basal metabolic rate was estimated (BMRest) from the participant’s weight considering age and sex according to the procedure outlined by Schofield, Schofield, & James (1985). The ratio of the reported daily energy intake EI to the BMRest was calculated for each participant; EI: BMRest. Individuals were included in the analysis only if their EI: BMRest reflected that their reported intake was at least 90% of the BMRest.

GPS - GIS Analysis

The El Paso, TX area was subdivided into Transportation Analysis Zones (TAZs). GIS information was employed to establish the characteristics of each TAZ. These included the number of households, population, household size, average household income, meters of roadways, number of intersections, meters of roadways per intersection, vehicle miles travelled on principle roads, number of links, intersection connectivity, number of stop signs, number of traffic lights, average slope, maximum slope, slope variance, number of parks, square meters of parks, total employment, basic employment, retail employment, services employment, numbers of sit down restaurants, fast food restaurants, hospitals, clinics, fire stations, police stations, libraries, museums, recreation centers, schools, and the number of robberies and number of murders.

For each 5-min period throughout the 7-day recording period the GPS coordinates recorded were used to identify the TAZ where the participant was located. The GIS characteristics of the participant’s TAZ area location were matched for each 5-min interval of the 7-day recording period.

At Home vs. Other Location Analysis

The mean eating bout characteristics were calculated separately for at home vs. away from home occurrences for each participant. These individual means were then used to calculate group means. In order to perform the analysis within subjects, participants’ data were only included in the analysis if they had at least five occurrences during the week at home and also at least five occurrences away from home. The away from home bouts were further subdivided into those eaten in restaurants, including both sit-down and fast-food restaurants, and other locations and mean bout characteristics recorded. Participants’ data were only included in this analysis if they had at least two occurrences during the week at restaurants and also at least two occurrences away from home at other locations. A mixed design ANOVA was performed on these data with normal weight vs. overweight as the between subjects variable and at home vs. away from home as the within subjects variable.

Results

There were no significant interaction terms present in the ANOVA with gender on any of the primary dependent variables. As a result, only overall group results, combining genders, are presented. The mean +/− S.E.M. total daily energy intakes were 1894 +/−81 KCal for normal weight and 2011 +/− 91 for overweight/obese participants.

Intakes at Home and Other Locations

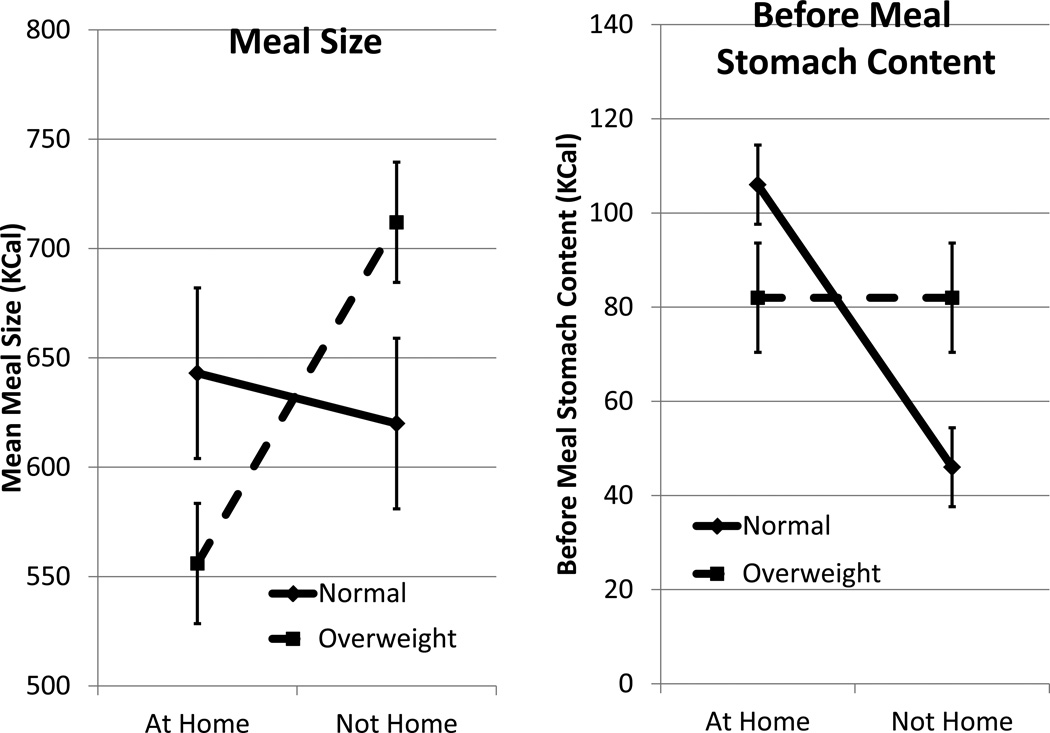

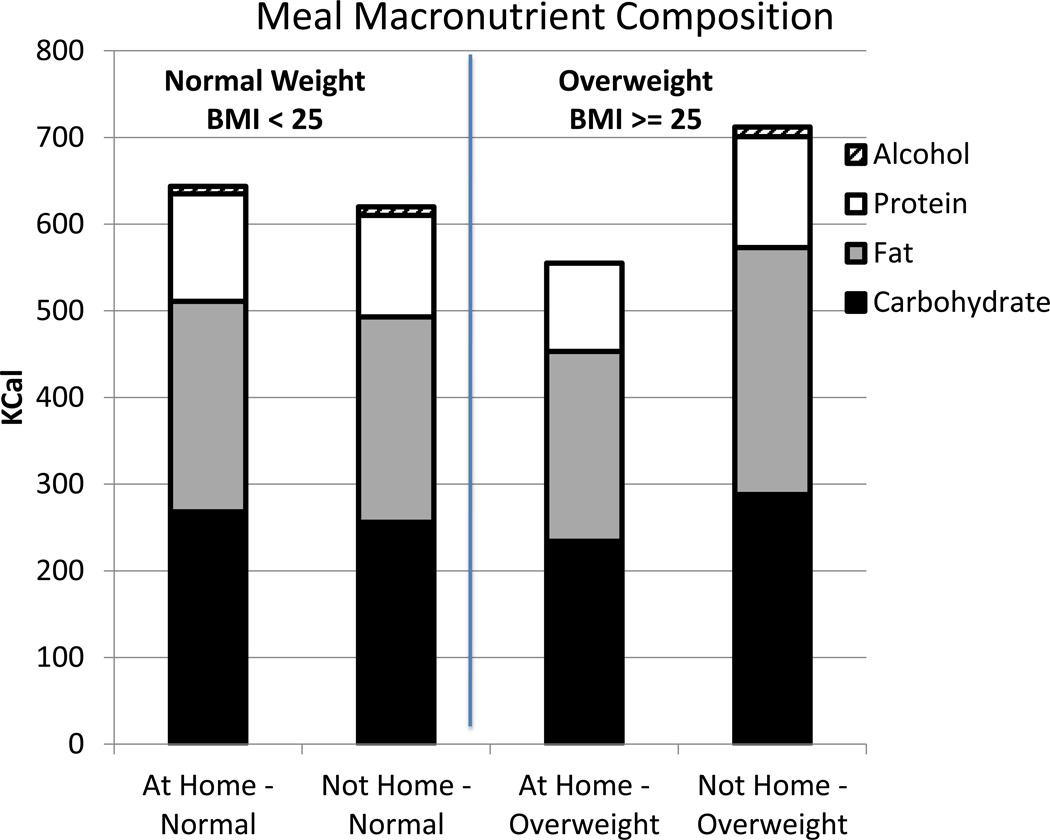

The mean meal sizes for normal weight and overweight/obese participants eaten at home and away from home are depicted in Figure 1 (left panel). The groups did not significantly differ overall, but there was a significant interaction between weight status and location (F(1,70) = 5.52, p<.05). This occurred because overweight/obese participants ate significantly smaller meals at home than they did away from home (t(43) = 3.08, p<.05) while normal weight participant ate equivalently sized meals at both locations. The overweight/obese participants ingested less food energy in the form of carbohydrate, fat, and protein at home than away from home (t(43) = 2.19, 2.65, 3.31, p<.05, respectively) while no significant differences were present for the normal weight individuals (Figure 2). In general, participants ate significantly more meals away from home than at home (F(1,70) = 6.93, p<.05) with normal weight and overweight/obese participants not significantly differing, eating 54% and 53% of their meals away from home respectively. The larger meal sizes eaten by overweight/obese participants away from home did not result from high levels of hunger as the groups’ before meal ratings of hunger did not significantly differ (5.24 and 5.18 respectively). In fact, the overweight/obese participants had larger estimated amounts of food remaining in their stomachs at the beginning of away from home meals than normal weight participants (t(43)=2.26, p<.05), (Figure 1) (Interaction term; F(1,70) = 4.35, p<.05).

Fig. 1.

The mean +/− S.E.M. meal sizes (KCal, left panel) and estimated before meal stomach contents (KCal, right panel) for meals eaten by normal weight (BMI<25 kg/m2) and overweight/obese (BMI>=25 kg/m2) participants at home and away from home.

Fig. 2.

The mean amounts of carbohydrate (black), fat (grey), protein (white), and alcohol (hatched) ingested in meals (KCal) eaten by normal weight (BMI<25 kg/m2, left two stacked bars) and overweight/obese (BMI>=25 kg/m2, right two stacked bars) participants at home and away from home.

Intakes at Restaurants and Other Locations Away from Home

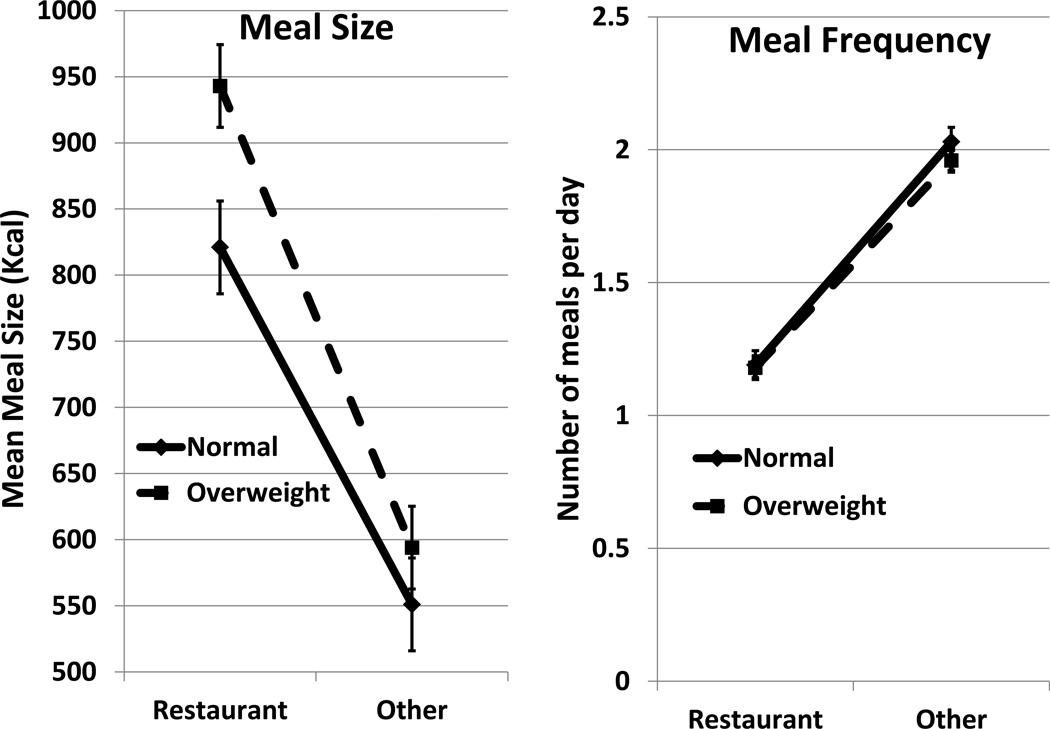

To investigate the possibility that the larger meals eaten by overweight/obese participants away from home might be due to a difference in the frequency or size of meals eaten in restaurants, the intakes in restaurants were compared to those at other away from home locations (Figure 3). Meal sizes in restaurants were 41% larger than those eaten in other locations (F(1,73) = 46.62, p<.05). Although the means for the overweight/obese participants were larger than for the normal weight participants both in restaurants and in other locations, these differences were not statistically significant. Fewer meals were eaten in restaurants than in other locations (F(1,73) = 92.63, p<.05). But, again, there were no significant differences between BMI groups.

Fig. 3.

The mean +/− S.E.M. meal sizes (KCal, left panel) and meal frequency (meals/d, right panel) for meals eaten by normal weight (BMI<25 kg/m2) and overweight/obese (BMI>=25 kg/m2) participants away from home at restaurants and other away from home locations.

GIS Differences Between Home and Other Locations

In order to better understand the differences between the participants’ home and away from home environments, the GIS differences between the home environments and the locations outside of the home where the participants were eating were compared (Table 1). Compared to eating at home, the participants ate outside of the home in areas that were characterized by lower population, lower household income and fewer households, kilometers of roads, sit down restaurants, and schools (F(1,70) = 29.16; 14.87; 42.54; 10.02; 7.31; 5.94, p<.05, respectively) and by larger total, retail, and services employment, greater area of parks, and more clinics, hospitals, libraries, and museums (F(1,70) = 42.27; 13.07; 33.47; 20.27; 7.59; 20.08; 10.26; 22.34, p<.05, respectively).

Table 1.

GIS characteristics of the home and outside of the home areas where meals occur.

| Environmental Characteristic | At Home | Away From Home |

|---|---|---|

| # Households | 1119 ± 63 | 545 ± 39↓ |

| Population | 3663 ± 244 | 1806 ± 132↓ |

| Average household size | 3.17 ± 0.07 | 3.45 ± 0.29 |

| Total employment | 951± 101 | 2669 ± 299↑ |

| Basic employment | 217 ± 50 | 202 ± 40 |

| Retail employment | 171 ± 16 | 355 ± 50↑ |

| Services employment | 564 ± 59 | 2111 ± 292↑ |

| Household income $/yr | 37668 ± 1587 | 30272 ± 1076↓ |

| Paved roadways (km) | 21.0 ± 1.9 | 13.1 ± 0.9↓ |

| # roadway intersections | 133 ± 20 | 111 ± 25 |

| Paved meters / intersection | 179 ± 5 | 169 ± 5 |

| # sitdown restaurants | 3.2 ± 0.3 | 1.9 ± 0.2↓ |

| # fastfood restaurants | 0.25 ± 0.06 | 0.16 ± 0.03 |

| Square meters of parks | 6116 ± 2511 | 8829 ± 1316↑ |

| Square kilometers of TAZ | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 2.2± 0.2 |

| Slope average (%) | 76 ± 7 | 89 ± 5 |

| Slope maximum (%) | 294 ± 39 | 245 ± 16 |

| Slope variance | 8171 ± 1666 | 8021 ± 624 |

| Vehicle travel (km) | 40849 ± 3859 | 39200 ± 2570 |

| # murders | 0.11 ± 0.04 | 0.05 ± 0.01 |

| # Robberies | 2.6 ± 0.3 | 2.9 ± 0.3 |

| # Clinics | 0.29 ± 0.07 | 0.61 ± 0.08↑ |

| # Fire Stations | 0.15 ± 0.03 | 0.08 ± 0.02 |

| # Hospitals | 0.13 ± 0.03 | 0.48 ± 0.08↑ |

| # Libraries | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.04 ± 0.01↑ |

| # Museums | 0.05 ± 0.02 | 0.44 ± 0.08↑ |

| # Parks | 0.66± 0.07 | 0.48 ± 0.06 |

| Acres of Parks | 15.5 ± 5.0 | 11.0 ± 2.2 |

| # Police Stations | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.01 ± 0.01 |

| # Recreation Centers | 0.10 ± 0.04 | 0.09 ± 0.02 |

| # Schools | 0.97± 0.13 | 0.50 ± 0.06↓ |

| # Stop Signs | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 1.6 ± 0.2 |

| # traffic lights | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 1.6 ± 0.1 |

| # links | 177 ± 25 | 142 ± 32 |

| Intersection connectivity | 1.39 ± 0.03 | 1.37 ± 0.04 |

Means are significantly (p < 0.05) smaller (↓) or larger (↑) away from home than at home.

Discussion

The present results indicate that being at home or away from home has differential effects on BMI groups. Overweight/obese individuals eat more when they are away from home while normal weight individuals eat about the same at home as away. The present study, however, employed only participants from the city of El Paso, Texas that has a high density of Hispanic individuals. Hence, the current sample may not be representative of the general population. As a result, Study 2 was performed reanalyzing the data from a large database of previously collected dietary diaries where both the foods ingested and the location of the meals were recorded.

STUDY 2

In order to investigate the influence of being at home or away on food intake in a diverse sample of normal weight, overweight, and obese individuals, the data on the intakes of free-living individuals that we have acquired with 7-d diet diaries in prior studies (de Castro, 1987a; 1987b; 1993a; 1994; 1999a; 1999b; 2004a; 2004b; 2005; 2006a; 2007, de Castro & de Castro, 1989) were reanalyzed.

Participants

The data were collected from 1009 individuals consisting of 388 males and 621 females. They were recruited as participants for a number of prior studies of intake control in humans (de Castro, 1987a; 1987b; 1993a; 1994; 1999a; 1999b; 2004a; 2004b; 2005; 2006a; 2007, de Castro & de Castro, 1989). The majority of the participants, 536, were paid $30 to participate and also received a detailed nutritional analysis of their intake although 354 individuals participated solely for the detailed nutritional analysis, while 119 were undergraduate students who satisfied a course requirement. The participants had a mean (+/− standard deviation) age of 34.2 +/− 6.2 years, weight of 69.0 +/− 15.9 kg, height of 1.67 +/− 0.10 m, and BMI of 24.6 +/− 4.6 kg/m2. In order to participate, the individuals could not be actively dieting, pregnant or lactating, on chronic medication, or alcoholic as ascertained with a demographic questionnaire.

Procedure

The participants were given a small (8 × 18 cm) pocket sized diary and were instructed to record in as detailed a manner as possible every item that they either ate or drank, the time they ate it, the amount they consumed, and how the food was prepared. They also recorded where the meal was ingested, at home, at a restaurant, friend’s house, work place etc. The participants initially recorded this information for a day and reviewed the records with the experimenter. They then recorded their intake for seven consecutive days. Afterwards they were contacted to clarify any ambiguities or missing data (de Castro, 1994; 1999).

Data Analysis

The foods reported in the diaries were analyzed in the same manner as in Study 1. Participants were separated into normal weight (BMI < 25 kg/m2) and overweight/obese (BMI >=25 kg/m2) groups. The intake for each participant eaten at home was compared to the intake for the same participant eaten outside of the home and outside of the home meals eaten at restaurants were compared to meals eaten at other non-home locations. The data were then compared with a 2 × 2 ANOVA for mixed designs.

Results

The mean +/− S.E.M. total daily energy intakes were 1977 +/−22 KCal for normal weight and 2224 +/− 30 for overweight/obese participants.

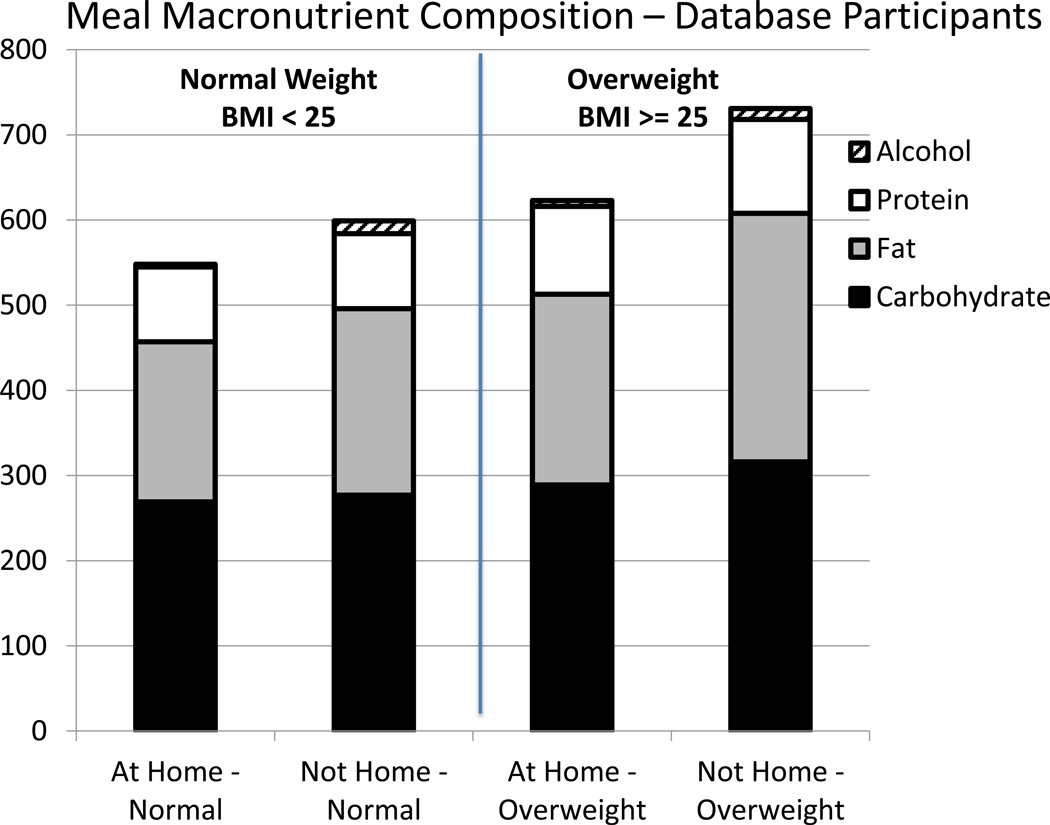

Intakes at Home and Other Locations

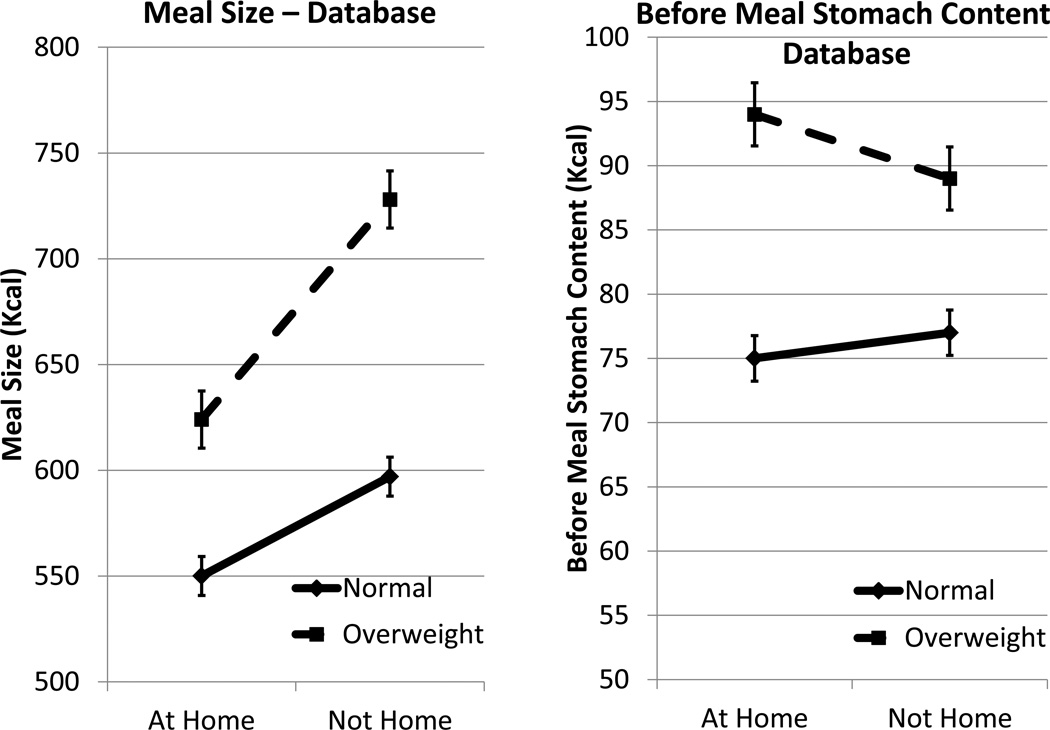

Compared to the normal weight group, meal sizes (total KCal) were significantly larger for the overweight/obese group (Figure 4; F(1,539) = 49.52, p<.05), ingesting significantly greater amounts of carbohydrate, fat, and protein (Figure 5; F(1,539) = 19.57; 57.58; 51.70, p<.05, respectively). There was a significant interaction between weight status and location (F(1,539) = 6.27, p<.05). This occurred because although both groups ate significantly smaller meals at home than they did away from home (F(1,539) = 38.60, p<.05), the difference was more than twice as large for the overweight/obese participants. The overweight/obese participants ingested less food energy in the form of carbohydrate, and fat at home than away from home (Figure 5; t(211) = 3.11; 6.66; p<.05, respectively), whereas for normal weight individuals the difference was only significant for fat intake (t(328)= 5.14, p<.05). Additionally, the difference in fat intake between at home and away from home was more than twice as large for the overweight/obese participants (F(1,539) = 10.66, p<.05). The larger meal sizes eaten by the overweight/obese participants were not due to higher levels of hunger as the groups did not differ in self-reported before meal hunger ratings and, in fact, the overweight/obese participants had larger estimated amounts of food remaining in their stomachs at the beginning of meals than normal weight participants (Figure 4, F(1,539) = 6.57, p<.05).

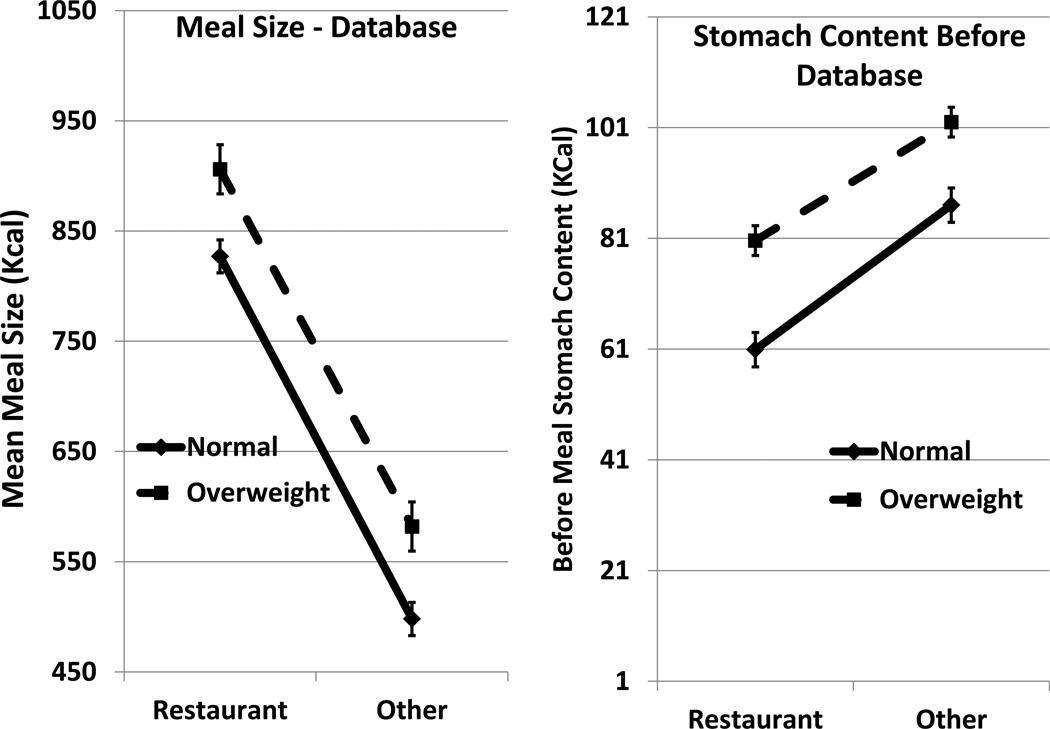

Fig. 4.

The mean +/− S.E.M. meal sizes (KCal, left panel) and estimated before meal stomach contents (KCal, right panel) for meals eaten by normal weight (BMI<25 kg/m2) and overweight/obese (BMI>=25 kg/m2) participants at home and away from home in Study with database data.

Fig. 5.

The mean amounts of carbohydrate (black), fat (grey), protein (white), and alcohol (hatched) ingested in meals (KCal) eaten by normal weight (BMI<25 kg/m2, left two stacked bars) and overweight/obese (BMI>=25 kg/m2, right two stacked bars) participants at home and away from home in Study 2 with database data.

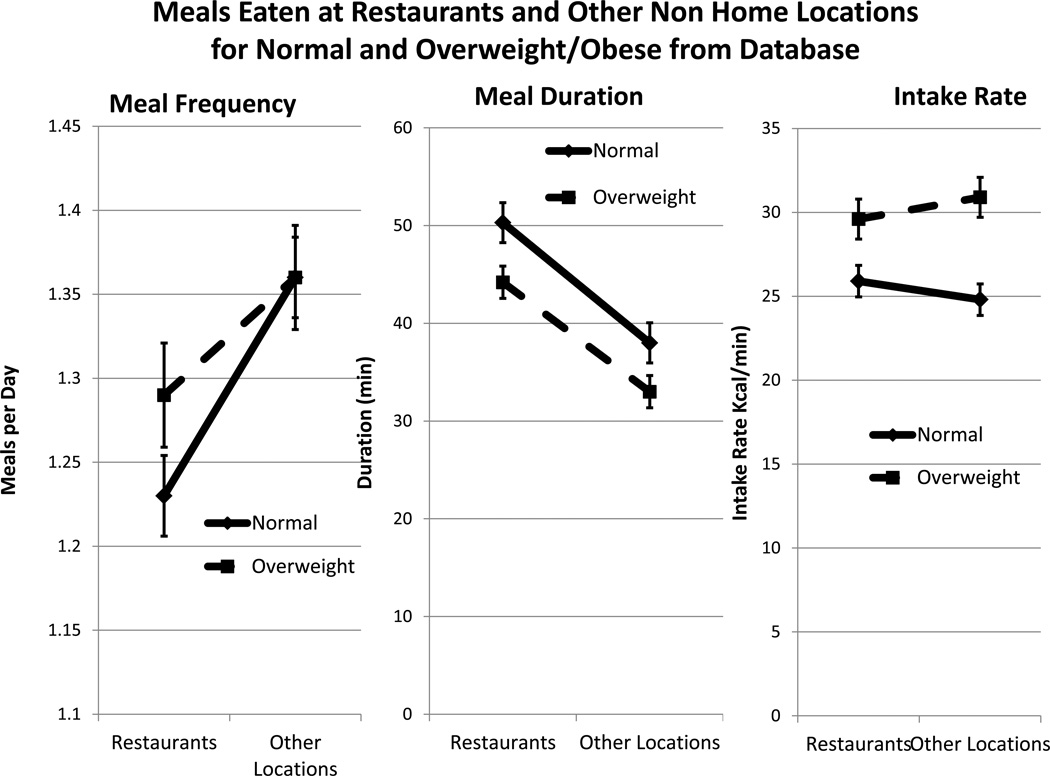

Intakes at Restaurants and Other Locations Away from Home

Meal sizes in restaurants were 60% larger than those eaten in other away from home locations (Figure 6; F(1,373) = 291.86, p<.05) and the overweight/obese participants ate significantly larger meals than the normal weight participants (F(1,373) = 12.01, p<.05). Fewer meals were eaten in restaurants than in other locations (Figure 7; F(1,373) = 5.84, p<.05), but there were no significant differences between BMI groups. The larger meal sizes eaten in restaurants and other non-home locations for the overweight/obese participants were not due to higher levels of hunger as the groups did not differ in self-reported before meal hunger ratings (5.05 and 5.11 respectively) and in fact the overweight/obese participants had larger estimated amounts of food remaining in their stomachs at the beginning of meals than normal weight participants (Figure 6; F(1,373) = 5.08, p<.05). Both groups ate for a longer period of time in restaurants than in other locations (Figure 7; F(1,373) = 25.25, p<.05) while the normal weight group had longer meal durations than the overweight/obese group (F(1,373) = 6.95, p<.05). There were no differences between location in the rate of intake, but the overweight/obese group ate significantly faster than the normal weight group (Figure 7; F(1,373) = 13.73, p<.05).

Fig. 6.

The mean +/− S.E.M. meal sizes (KCal, left panel) and estimated before meal stomach contents (KCal, right panel) for meals eaten by normal weight (BMI<25 kg/m2) and overweight/obese (BMI>=25 kg/m2) participants away from home at restaurants and other away from home locations in Study 2 with database data.

Fig. 7.

The mean +/− S.E.M. meal frequency (meals/d, left panel) meal duration (min, center panel), and rate of intake in the meal (KCal/min, right panel) for meals eaten by normal weight (BMI<25 kg/m2) and overweight/obese (BMI>=25 kg/m2) participants away from home at restaurants and other away from home locations in Study 2 with database data.

General Discussion

There is considerable evidence that the overweight/obese tend to under report their intakes in diaries to a greater extent that normal weight individuals (Bandini, Schoeller, Cyr, & Dietz, 1990; Maurer, Taren, Teixeira, Thomson, Lohman, Going, & Houtkooper, 2006; Tooze, Subar, Thompson, Troiano, Schatzkin, & Kipnis, 2004). This suggests that the present results may be vulnerable to spurious outcomes due to differential underreporting. Overall intake differences between the BMI groups in Study 2, however, are in the opposite direction, with overweight/obese participants reporting larger meals. Additionally, the differential effects that were observed between the BMI groups’ intakes when meals eaten at home were compared to those eaten at other locations could not be due to differential underreporting as these differences were assessed within subjects where individual differences in underestimation would not be a factor. Thus, it is unlikely that differential underestimation of intake could account for the present observed differences between at home and away from home intakes.

The present findings also suggest that the differential responses of BMI groups to eating at home vs. eating away from home may be generalized as it appears to be present not only in the sample from El Paso, Texas, but was also detectable in a national database sample. The two samples differed in that in Study 2 the overweight/obese group ingested larger meals than the normal weight group, while no significant difference was detected in Study 1. Regardless, in both samples overweight/obese appear to be particularly vulnerable to overeating when they are outside of the home.

It is not clear exactly why overweight individuals may be more susceptible to overeating outside of the home environment than normal weight individuals. They appear to eat larger meals outside of the home regardless of whether they are eating in restaurants or in other outside of the home locations. It does not appear to be due to differences in the subjective levels of hunger as there were no differences in self-reported hunger between the groups. It also does not appear to be due to differences in the deprivation level between the groups as the overweight were estimated to have more food remaining in their stomachs at the time of eating outside of the home than the normal weight group. It does not appear to be due to the availability of restaurants as the groups did not differ in meal sizes or frequencies of eating in restaurants. It also does not appear to be due to differences in the characteristics of the environments occupied by the overweight/obese as the GIS data on the characteristics of the at home and away from home environments did not significantly differ between the BMI groups.

It appears then that the overweight/obese are differentially responsive to the characteristics of the away from home environments. It is possible that there is a heightened responsiveness of the overweight/obese to the high levels of food related stimuli outside of the home. Indeed, eating outside of the home has been linked to overweight and obesity (Bezerra & Sichieri, 2009). In addition, for many years the obese have been postulated to be over responsive to external stimuli (Schachter, 1968; Tuomisto, Tuomisto, Hetherington, & Lappalainen, 1998; Cohen & Farley, 2008; Wansink, 2010; Wansink, Payne, & Chandon, 2007) and the present findings are compatible with such a hypothesis. Finally, it has been shown that people inherit different responsiveness’ to external food related stimuli (de Castro & Plunkett, 2002; de Castro 1993b; 1997; 1999b; 1999c; 2001a; 2001b; 2006b). So, it can reasonably be speculated that one of the reasons that the overweight/obese become overweight/obese is because of an inherited predisposition to be highly reactive to food related cues in the environment.

The present study was observational in nature and as such cannot be used to make causal inferences. The present findings, however, does provide a speculative hypothesis as to how the built environment may be contributing to the obesity epidemic. The General Model of Intake Regulation (de Castro & Plunkett, 2002) postulates that individuals inherit different susceptibilities to environmental influences, such that some individuals will react to a given environment by overeating while others who did not inherit susceptibility will not. In recent years there has been a marked growth in the number and variety of restaurants and food outlets (Cohen, 2008) and obesity appears to be associated with the density of all restaurants (Inagami, Cohen, Brown, & Asch, 2009) and convenience stores (Galvez, Hong, Choi, Liao, Godbold, & Brenner, 2009). Based upon the present findings it can be speculated that this growth in food availability outside of the home may have particularly affected those who are vulnerable to the influence of food availability, causing overeating and overweight.

Highlights.

Meal patterns of normal vs overweight individuals at home vs. elsewhere are studied

Overweight participants ate larger meals away from home

Meal sizes in restaurants were larger than other non-home locations

Overweight individuals may be more responsive to cues for eating away from home

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bandini LG, Schoeller DA, Cyr HN, Dietz WH. Validity of reported energy intake in obese and nonobese adolescents. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1990;52:421–425. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/52.3.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezerra IN, Sichieri R. Eating out of home and obesity: a Brazilian nationwide survey. Public Health and Nutrition. 2009;12(11):2037–2043. doi: 10.1017/S1368980009005710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth DA. A simulation model of psychobiosocial theory of human food-intake control. International Journal for Vitamin and Nutrition Research. 1988;58:119–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen DA. Obesity and the Built Environment: Changes in environmental cues causes energy imbalances. International Journal of Obesity. 2008;32:S137–S142. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen D, Farley TA. Eating as an Automatic Behavior. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2008;5(1):A23–A29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Castro JM. Macronutrient relationships with meal patterns and mood in the spontaneous feeding behavior of humans. Physiology and Behavior. 1987a;39:561–569. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(87)90154-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Castro JM. Circadian rhythms of the spontaneous meal pattern, macronutrient intake and mood of humans. Physiology and Behavior. 1987b;40:437–466. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(87)90028-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Castro JM. The effects of the spontaneous ingestion of particular foods or beverages on the meal pattern and overall nutrient intake of humans. Physiology and Behavior. 1993a;53(6):1133–1144. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(93)90370-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Castro JM. A twin study of genetic and environmental influences on the intake of fluids and beverages. Physiology and Behavior. 1993b;54(4):677–687. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(93)90076-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Castro JM. Methodology, correlational analysis, and interpretation of diet diary records of the food and fluid intakes of free-living humans. Appetite. 1994;23:179–192. doi: 10.1006/appe.1994.1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Castro JM. Inheritance of social influences on eating and drinking in humans. Nutrition Research. 1997;17:631–648. [Google Scholar]

- de Castro JM. Measuring real-world eating behavior. Progress in Obesity Reserach. 1999a;8:215–221. [Google Scholar]

- de Castro JM. Inheritance of premeal stomach content influences on eating and drinking in free living humans. Physiology and Behavior. 1999b;66:223–232. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(98)00291-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Castro JM. Inheritance of hunger relationships with food intake in free living-humans. Physiology and Behavior. 1999c;67(2):249–258. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(99)00065-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Castro JM. Heritability of diurnal changes in food intake in free-living humans. Nutrition. 2001a;17:713–720. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(01)00611-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Castro JM. Palatability and intake relationships in free-living humans: Influence of heredity. Nutrition Research. 2001b;21(7):935–945. doi: 10.1016/s0271-5317(01)00323-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Castro JM. The time of day of food intake influences overall intake in humans. Journal of Nutrition. 2004a;134:104–111. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.1.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Castro JM. Dietary energy density is associated with heightened intake in free-living humans. Journal of Nutrition. 2004b;134:335–341. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.2.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Castro JM. Stomach filling may mediate the influence of dietary energy density on the food intake of free-living humans. Physiology and Behavior. 2005;86(1–2):32–45. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Castro JM. Varying levels of food energy self-reporting are associated with between group but not within subjects differences in food intake. Journal of Nutrition. 2006a;136:1382–1388. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.5.1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Castro JM. Heredity influences the dietary energy density of free-living humans. Physiology and Behavior. 2006b;87:192–198. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Castro JM. The time of day and the proportions of macronutrients eaten are related to total daily food intake. British Journal of Nutrition. 2007;98:1077–1083. doi: 10.1017/S0007114507754296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Castro JM, de Castro ES. Spontaneous meal patterns in humans: influence of the presence of other people. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1989;50:237–247. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/50.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Castro JM, Plunkett S. A general model of intake regulation. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2002;26:581–595. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(02)00018-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffey KJ, Gordon-Larsen P, Jacobs DR, Jr, Williams OD, Popkin BM. Differential associations of fast food and restaurant food consumption with 3-y change in body mass index: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2007;85(1):201–208. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.1.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvez MP, Hong L, Choi E, Liao L, Godbold J, Brenner B. Childhood obesity and neighborhood food-store availability in an inner-city community. Academic Pediatrics. 2009;9(5):339–343. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagami S, Cohen DA, Brown AF, Asch SM. Body mass index, neighborhood fast food and restaurant concentration, and car ownership. Journal of Urban Health. 2009;86(5):683–695. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9379-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holsten JE. Obesity and the community food environment: a systematic review. Public Health and Nutrition. 2009;12(3):397–405. doi: 10.1017/S1368980008002267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins A. The pattern of gastric emptying: a new view of old results. Journal of Physiology (London) 1966;182:144–150. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1966.sp007814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt JN, Knox MT. Regulation of gastric emptying. In: Code CF, Heidel W, editors. Handbook of Physiology: Alimentary Canal, Vol 4: Motility. Washington D.C.: American Physiological Society; 1968. pp. 1917–1935. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt JN, Stubbs DF. The volume and content of meals as determinants of gastric emptying. Journal of Physiology (London) 1975;245:209–225. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1975.sp010841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk SF, Penney TL, McHugh TL. Characterizing the obesogenic environment: the state of the evidence with directions for future research. Obesity Review. 2010;11(2):109–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Harmer P, Cardinal BJ, Bosworth M, Johnson-Shelton D, Moore JM, Acock A, Vongjaturapat N. Built environment and 1-year change in weight and waist circumference in middle-aged and older adults: Portland Neighborhood Environment and Health Study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2009;169(4):401–408. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurer J, Taren DL, Teixeira PJ, Thomson CA, Lohman TG, Going SB, Houtkooper LB. The psychosocial and behavioral characteristics related to energy misreporting. Nutrition Review. 2006;64(2 Pt 1):53–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2006.tb00188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papas MA, Alberg AJ, Ewing R, Helzlsouer KJ, Gary TL, Klassen AC. The built environment and obesity. Epidemiology Review. 2007;29:129–143. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxm009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield WN, Schofield C, James WPT. Basal metabolic rate - review and prediction, together with an annotated bibliography of source material. Human Nutrition,: Clinical Nutrition. 1985;39c(Suppl.1):1–96. [Google Scholar]

- Sallis JF, Glanz K. Physical activity and food environments: solutions to the obesity epidemic. Milbank Quarterly. 2009;87(1):123–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00550.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schachter S. Obesity and eating: Internal and external cues differentially affect the eating behavior of obese and normal subjects. Science. 1968;161:751–756. doi: 10.1126/science.161.3843.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schröder H, Föto M, Covas MI. Association of fast food consumption with energy intake, diet quality, body mass index and the risk of obesity in a representative Mediterranean population. British Journal of Nutrition. 2007;98(6):1274–1280. doi: 10.1017/S0007114507781436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tooze JA, Subar AF, Thompson FE, Troiano R, Schatzkin A, Kipnis V. Psychosocial predictors of energy underreporting in a large doubly labeled water study. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2004;79(5):795–804. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.5.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trasande L, Cronk C, Durkin M, Weiss M, Schoeller DA, Gall EA, Hewitt JB, Carrel AL, Landrigan PJ, Gillman MW. Environment and obesity in the National Children's Study. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2009;117(2):159–166. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuomisto T, Tuomisto MT, Hetherington M, Lappalainen R. Reasons for initiation and cessation of eating in obese men and women and the affective consequences of eating in everyday situations. Appetite. 1998;30(2):211–222. doi: 10.1006/appe.1997.0142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Beydoun MA. The obesity epidemic in the United States--gender, age, socioeconomic, racial/ethnic, and geographic characteristics: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Epidemiology Review. 2007;29:6–28. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxm007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Beydoun MA, Liang L, Caballero B, Kumanyika SK. Will all Americans become overweight or obese? estimating the progression and cost of the US obesity epidemic. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16(10):2323–2330. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wansink B. From mindless eating to mindlessly eating better. Physiology and Behavior. 2010;100(5):454–463. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wansink B, Payne CR, Chandon P. Internal and external cues of meal cessation: the French paradox redux? Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15(12):2920–2924. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]