Abstract

There have been several reports on the relationship between toxocariasis and eosinophilia, but all have been limited to the areas of Seoul or Gangwon-do. In the present study, we investigated the seroprevalence of toxocariasis among eosinophilia patients in Chungcheongnam-do, the central district of Korea. Among the 101 patients tested, 51 (50.5%) were identified as positive by Toxocara ELISA, and 46 (45.5%) were confidently diagnosed with toxocariasis because of absence of any other cause of eosinophilia. Whereas 22 of 42 seropositive patients (52.3%) had a recent history of consuming raw livers, especially the cow liver, only 1 of 25 seronegative patients (4%) had done so (P<0.01). From these results, we could confirm that toxocariasis is related to eosinophilia, and infer that ingestion of raw cow liver plays a vital role in the transmission of toxocariasis in Chungcheongnam-do.

Keywords: Toxocara canis, Toxocara cati, toxocariasis, eosinophilia, Chungcheongnam-do

Parasitic infections have long been known as a cause of eosinophilia. Recently, Toxocara canis or Toxocara cati was found to be a significant cause of the peripheral blood eosinophilia. Moreover, there have been several reports on the correlation between toxocariasis and eosinophilia; among the findings, IgG antibodies to Toxocara spp. were higher in the eosinophilic group than in the non-eosinophilic group, and a 4-year-old girl with eosinophilia was proved to have toxocariasis [1,2]. Recently, this correlation has actively been studied in Korea. Seventy (70) among 103 eosinophilia patients (68%) were diagnosed with T. canis by ELISA, and 2/3 of patch pulmonary infiltrates were found to be seropositive for Toxocara spp. [3,4]. In another study, seropositivity for Toxocara was reported to be a major cause of eosinophilia [5].

Toxocariasis is usually asymptomatic and self-limiting, but can manifest clinically according to the worm burden or infected organs. Visceral larva migrans due to Toxocara spp. can result in eosinophilic pleural effusion, hepatic abscess, retinal detachment, atopic myelitis, or other maladies [6-9]. Human infections with T. canis occur in either of 2 ways, by accidental ingestion of embryonated eggs, or by consumption of uncooked liver containing encapsulated larvae. In adults, transmission through uncooked cow liver is the most common cause of toxocariasis, though pig, lamb, and chicken livers also have been reported as sources [10]. Considering the habitual intake of the raw liver in Korea, toxocariasis probably is prevalent nationwide, but especially in rural areas. For example, in Whacheon-gun, Gangwon-do, the seroprevalence among healthy inhabitants was found to be approximately 5% [11]. However, previous studies on toxocariasis have been limited to the areas of Seoul or Gangwon-do; there had been no reports on, for example, the Chungcheongnam-do prevalence. The present study was conducted to determine the proportion of patients with eosinophilia who shows seropositivity against Toxocara antigen by ELISA.

From April 2009 to June 2011, patients visiting the Department of Internal Medicine, Dankook University Hospital, were screened for their eosinophil count, and those with eosinophilia were selected irrespective of the presence of related symptoms. Eosinophilia was defined as a level higher than 5% of the WBC count. Total 101 patients were selected, including 87 inhabitants of Chungcheongnam-do and 14 of Gyonggi-do. The former patients were living in Cheonan-si (n=48), Asan-si (5), Yeongi-gun (5), Hongseong-gun (4), Daejeon-si (3), Boryong-si (3), Gongju-si (2), Yesan-gun (1), Dangjin-gun (1), Taean-gun (1), and Cheongyang-gun (1). The latter were living in Pyeongtaek-si (4), Anseong-si (9), and Goyang-gun (1). Eosinophil percentage of the selected patients was 9.9% in average (5.0-50.2%); 75 were in 5.0-9.9%, 21 were in 10.0-29.9%, and 5 were over 30%.

The serologic diagnosis was made at the Seoul Clinical Laboratory (SCL) (Seoul, Korea). Specific IgG antibodies to Toxocara ES antigen were measured using a Toxocara ELISA kit (Bordier Affinity Products, Crissier, Switzerland), which has a 91% sensitivity and a 86% specificity [12]. The results were identified as positive according to the daily reference control. In addition, the patients were questioned regarding their history of consuming raw livers, contact with a dog or cat, symptoms upon visiting our clinic, the presence of symptoms related to toxocariasis, and others. The chi-square test was used in analytical assessment, and the differences were considered to be statistically significant when the P-value obtained was less than 0.05.

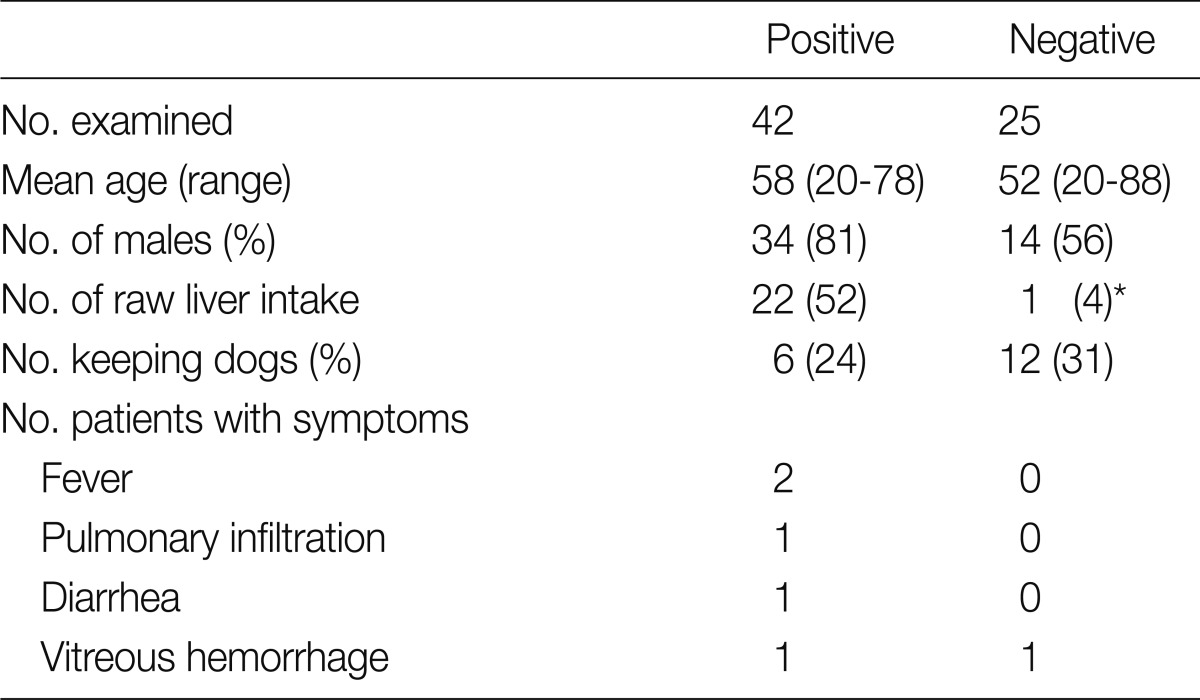

The mean age of the patients was 53.8 years (17-76), and the ratio of men to women was 62:39. Among the 101 sera tested, 51 (50.5%) were identified as positive by Toxocara ELISA, among which the ratio of men to women was 39:12. Forty-six patients (45.5%) were confidently diagnosed with toxocariasis, due to the absence of any other cause of eosinophilia. As for the remaining patients, bronchial asthma (n=2), allergic rhinitis (2), and Trichinella spiralis infection (1) were suspected as the causes. Overall, detailed information could be obtained from only 67 patients, among which 42 were positive for Toxocara (Table 1). While 22 of these 42 seropositive patients (52.3%) had a recent history of consuming raw livers, only 1 of 25 seronegative patients (4%) had such a history. This difference was proved to be statistically significant (P<0.01). The liver was mostly from cows, and the chicken liver had been consumed by 1 patient. All the experiences of raw-liver consumption were observed in males except for 1 seropositive female. The history of keeping dogs at home was higher in the seropositive group, but proved to be statistically insignificant. Most of the patients, all but 2, did not complain of any signs or symptoms related to toxocariasis. Of these 2, pulmonary patchy infiltration and severe diarrhea were observed in a patient, while the other complained of fever, chill, and headache. All of them were treated with albendazole for 5 days (400 mg/b.i.d.), and treated again for 7 days in the case of persistent eosinophilia after 3 months. This eventually lowered their eosinophil count.

Table 1.

Differences according to Toxocara seropositivity in eosinophilia patients

*Statistically significant (P<0.05).

Our results revealed toxocariasis to be one of the most common causes of peripheral eosinophilia in Chungcheongnam-do, accounting for 45.5% of the cases. Compared with other nationals, Koreans, even otherwise healthy individuals, frequently have been diagnosed with eosinophilia [13]. In fact, the incidence of eosinophilia in Korea is as high as 4.0-12.2%, whereas in Canada it is only 0.1% [13]. The main causes of eosinophilia are infectious diseases stemming from parasites, or allergies, malignancies, drug hypersensitivity reactions, or idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) [14]. According to recent studies, the abnormally high incidence of eosinophilia among Koreans can be attributed to the widespread morbidity of parasitic infections, especially toxocariasis [3,4]. Nevertheless, serologic tests for toxocariasis frequently have been neglected in the clinical practice, due to ignorance of the high prevalence of toxocariasis, or misdiagnoses as HES or clonal eosinophilia, leading to antileukemic therapy [13]. Toxocara ELISA is essential for evaluation of unknown eosinophilia in Korea where consumption of raw livers remains a cultural habit.

In the present study, more than a half of the cases of seropositivity could be correlated with the experience of eating raw liver, mostly the cow liver. Raw cow liver chops have long been consumed by many Koreans in the belief that it is a health-promoting food, thereby raising the risk of toxocariasis. According to a previous report, only 25.0% of seronegative patients had a recent history of eating raw cow liver, compared with 87.5% of seropositive patients [10]. An older survey found a larva recovery rate of 11.8% from the beef liver [15], and cows are typically infected by ingestion of the soil contaminated with eggs. With regard to dog toxocariasis, its prevalence has continuously fallen over the years, from 18.9% in 1976, to 8.2% in 1995, and to 0.9% in 2004 [16], though according to a previous study, the rate could well be higher in abandoned dogs [17]. Hence, by now, the prevalence might be about the same considering the rapid increases in the numbers of abandoned dogs or cats. Active surveillance of Toxocara infection in such animals could be a useful preventive measure.

Livers from other animals also can contribute to the spread of toxocariasis. Raw chicken liver, for example, was the cause of a Korean girl's hospitalization for toxocariasis [18]. In the present study, 1 patient had a history of eating raw chicken liver, which probably was the source of infection in that case. However, none of the remaining patients reported any history of ingesting cow livers, especially in women. A history of keeping dogs might be another cause of toxocariasis, although such histories were not observed more frequently in seropositive patients in the present study. It should be noted that some seropositive patients lack both histories, that is, those of raw cow liver ingestion and keeping dogs. Since transmission through consumption of raw cow meat had also been reported as a cause of toxocariasis [10], additional investigations should be conducted on other varieties of meat.

In the present study, almost none of the seropositive patients examined showed symptoms associated with toxocariasis; only 2 patients did. The relationship between vitreous hemorrhage and toxocariasis requires further investigation. Nonetheless, toxocariasis can cause serious conditions, such as atopic myelitis [9]; for that reason, more attention should be paid to its control.

References

- 1.Karadam SY, Ertug S, Ertabaklar H, Okyay P. The comparison of IgG antibodies specific to Toxocara spp. among eosinophilic and non-eosinophilic groups. New Microbiol. 2008;31:113–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sayar D, Mazilis A, Kassem E, Klein A. Toxocariasis as a cause of hypereosinophilia. Harefuah. 2009;148:14–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kwon NH, Oh MJ, Lee SP, Lee BJ, Choi DC. The prevalence and diagnostic value of toxocariasis in unknown eosinophilia. Ann Hematol. 2006;85:233–238. doi: 10.1007/s00277-005-0069-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoon YS, Lee CH, Kang YA, Kwon SY, Yoon HI, Lee JH, Lee CT. Impact of toxocariasis in patients with unexplained patchy pulmonary infiltrate in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2009;24:40–45. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2009.24.1.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim YH, Huh S, Chung YB. Seroprevalence of toxocariasis among healthy people with eosinophilia. Korean J Parasitol. 2008;46:29–32. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2008.46.1.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ashwath ML, Robinson DR, Katner HP. A presumptive case of toxocariasis associated with eosinophilic pleural effusion: case report and literature review. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;71:764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jung JK, Jung JT, Lee CH, Kim EY, Kwon JG, Kim BS. A case of hepatic abscess caused by Toxocara. Korean J Hepatol. 2007;13:409–413. doi: 10.3350/kjhep.2007.13.3.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park SP, Park I, Park HY, Lee SU, Huh S, Magnaval JF. Five cases of ocular toxocariasis confirmed by serology. Korean J Parasitol. 2000;38:267–273. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2000.38.4.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee JY, Kim BJ, Lee SP, Jeung YJ, Oh MJ, Park MS, Paeng JW, Lee BJ, Choi DC. Toxocariasis might be an important cause of atopic myelitis in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2009;24:1024–1030. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2009.24.6.1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi D, Lim JH, Choi DC, Paik SW, Kim SH, Huh S. Toxocariasis and ingestion of raw cow liver in patients with eosinophilia. Korean J Parasitol. 2008;46:139–143. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2008.46.3.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park HY, Lee SU, Huh S, Kong Y, Magnaval JF. A seroepidemiological survey for toxocariasis in apparently healthy residents in Gangwon-do, Korea. Korean J Parasitol. 2002;40:113–117. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2002.40.3.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacquier P, Gottstein B, Stingelin Y, Eckert J. Immunodiagnosis of toxocarosis in humans: Evaluation of a new enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:1831–1835. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.9.1831-1835.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lim JH. Foodborne Eosinophilia due to visceral larva migrans: A disease abandoned. J Korean Med Sci. 2012;27:1–2. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2012.27.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rothenberg ME. Eosinophilia. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1592–1600. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199805283382206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lim JH. Images in clinical tropical medicine: Hepatic visceral larva migrans of Toxocara canis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;82:520–521. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim YH, Huh S. Prevalence of Toxocara canis, Toxascaris leonina and Dirofilaria immitis in dogs in Chuncheon, Korea (2004) Korean J Parasitol. 2005;43:65–67. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2005.43.2.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cho SY, Kang SY, Ryang YS. Helminth infections in the small intestine of stray dogs in Ejungbu City, Kyunggi-do, Korea. Korean J Parasitol. 1981;19:55–59. doi: 10.3347/kjp.1981.19.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park MS, Ahn YJ, Moon KR. Familial case of visceral larval migrans of Toxocara canis after ingestion of raw chicken liver. Korean J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;13:70–74. [Google Scholar]