Abstract

Aim

This article is a report of a review that aimed to synthesize qualitative and quantitative evidence of ‘off-shifts’ (nights, weekends and/or holidays) on quality and employee outcomes in hospitals.

Background

Healthcare workers provide 24-hour-a-day, 7-day-a-week service. Quality and employee outcomes may differ on off-shifts as compared to regular hours.

Data sources

Searches for studies occurred between the years 1985–2011 using computerized databases including Business Source Complete, EconLit, ProQuest, PubMed and MEDLINE.

Review design and methods

Design was a mixed-method systematic review with quantitative and qualitative studies. To be included, studies met the following criteria: (1) the independent variable was an off-shift; (2) the article was a research study and peer-reviewed; (3) the article could be obtained in English; and (4) the article pertained to health care. Studies were not excluded on design.

Results

Sixty studies were included. There were 37 quality outcome, 19 employee outcome and four qualitative studies. In the quality outcome studies, researchers often used quantitative, longitudinal study designs with large sample sizes. Researchers found important differences between patients admitted on weekends and mortality. Important differences were also found between nighttime birth and mortality and rotating night work and fatigue, stress and low mental well-being. Most studies (9 of 12) did not find an important association between patients admitted at night and mortality.

Conclusion

Patient outcomes on weekends and employee outcomes at night are worse than during the day. It is important to further investigate why care on off-shifts differs from weekly day shifts.

Keywords: After hours, fatigue, mixed-method systematic review, mortality, nursing, patient outcomes, patient safety

Introduction

Nurses provide 24-hour, 7 day-a-week care to patients; and, nursing care often extends beyond the traditional 9–5 Monday through Friday work week. Researchers have found that the routine of 7 AM to 7 PM, Monday through Friday, is not representative of the environment where most nursing work takes place (Hamilton et al. 2010). To ensure patient coverage, some nurses work after hours or out of hours, or otherwise known as ‘off-shifts’, which include nights, weekends and holidays. On off-shifts, there may be lower levels of nurse staffing and less resources available. Specifically for weekends, researchers have found that clinical personnel staffing levels in acute care hospitals tend to be lower on weekends than on weekdays; and, hospitals function less effectively on weekends (Bell & Redelmeier 2001).

Night nurses may have higher levels of fatigue than day nurses. In other industries where employees work around the clock, researchers found that shift workers rarely report getting the recommended eight hours of sleep (Akerstedt 2003). In addition, night nurses may suffer from sleep disturbances, which may have an impact on patient safety. Sleep deprivation jeopardizes not only patient safety, but also the safety and general health of nurses themselves (Rogers et al. 2004). It is often the second half of the night where nurses reported that they frequently struggle to stay awake (Berger & Hobbs 2006). In addition, working at night can impact employees’ circadian rhythm, social and family life and overall health such as digestive and health conditions (Rosa & Colligan 1997).

The review

Aim

The aim of this review was to synthesize the evidence on off-shifts and quality patient care. The term off-shift is often used interchangeably with terms including, but not limited to, as ‘out-of-hours’, ‘after-hours’ and ‘off-peak hours’. For simplicity, we use the term ‘off-shift’ throughout this review. An additional aim was to synthesize the evidence on healthcare providers who work night shift, or rotated to work night shift and their risk for sleep disorders or decreased well-being as compared to providers who worked more regular hours.

Design

A systematic review including quantitative and qualitative studies of the off-shift literature in hospitals was conducted. The review process was guided by the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination manual from York University on identifying and organizing published literature for health care (University of York 2009). This manual provides systematic review methods including how to search for evidence, develop inclusion and exclusion criteria, extract data, appraise evidence and synthesize the results. The authors also give guidelines on how to synthesize relevant qualitative studies to help interpretation of the quantitative findings (University of York 2009). To be comprehensive, all types of study designs were included in the review. Due to study heterogeneity, a meta-analysis could not be performed.

Search methods

Searches for studies occurred between the years 1985–2011 using computerized databases. These databases included Business Source Complete, EconLit, ProQuest, PubMed and MEDLINE to identify studies that may have not been located in health-related databases. Key words included ‘shift work’, ‘nights’, ‘weekends’, ‘off-peak hours’, ‘off-shifts’, ‘patient outcomes’, ‘productivity’ and ‘quality’. The reference lists of included articles were reviewed to retrieve additional studies. To be included in the review, the studies meet the following criteria: (1) the independent variable of interest was an off-shift; (2) the article was a research study and peer-reviewed; (3) the article could be obtained in English; and (4) the article pertained to health care.

Search outcome

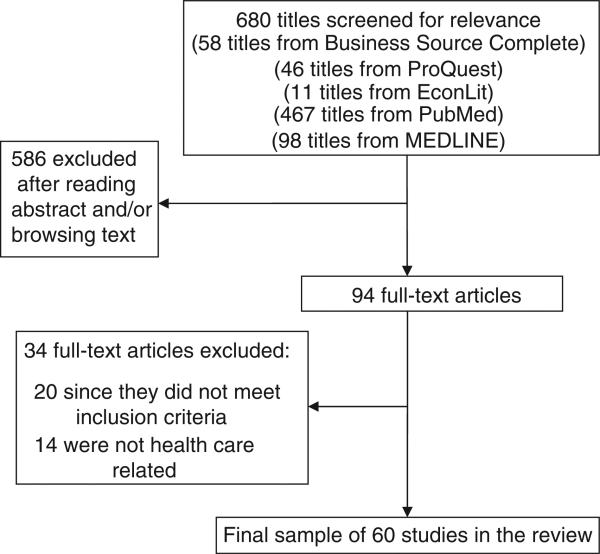

The search identified 680 titles and abstracts, which were reviewed to determine eligibility. Five hundred and eighty-six of these were excluded after reading the abstract and/or browsing text: A total of 94 full-text articles were identified as potentially eligible. Of these, 34 were further excluded because off-shifts were not clearly defined, independent and dependent variables were not pertinent to the search and/or lack of information. Sixty articles were reviewed. Figure 1 displays the flow chart of the study selection process. Studies were not excluded based on the quality of the research methodology.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study selection process.

Quality appraisal

An article quality assessment tool (available from authors) was adopted and used to appraise evidences for the quantitative studies included in this review (Aboelela et al. 2007). This tool was adapted from previously published review, which used standardized, well developed methodology and allowed assessment of study quality on five domains: These domains include description of setting, sample and study design; representativeness of study population; defined independent variables and outcomes, statistical approach and clarity of the results (See supporting information Table S1 in the online version of the article in Wiley Online Library). Based on the five domains, the methodological quality of each study was graded as A (completely adequate with detailed description), B (partially adequate with fair description) and C (not specified or inadequate with poor description) or (not applicable). The quality appraisal outcomes are available as a concise web-based (See supporting information Table S2 in the online version of the article in Wiley Online Library). The full evidence-based tables for the 60 studies are available from the authors. Due to the diversity of settings, samples and study design, a meta-analysis of the grades could not be calculated. Qualitative research studies were appraised using the Dixon-Wood et al. (2004) criteria presented in Table S1 in the online version of the article in Wiley Online Library.

Data abstraction and synthesis

Data were abstracted by the first author (PdC) and all abstracted data were reviewed by the senior author (PWS). The following data were abstracted: setting, sample, study design, definition of off-shift studied (e.g. nights, nights and rotation, weekends, holidays and/or combination), conceptualization and operationalization of outcome(s) (for quantitative studies) and results. Data synthesis included examining relationships between how researchers defined off-shifts and what type of outcomes were studied. The studies were first divided by type of outcome and/or finding (e.g. patient or employee). Quantitative patient outcome studies were further grouped by specific independent variables (e.g. time of admission/discharge, time of birth, time of procedures and nurse staffing).

Results

There were 60 studies representing a diversity of countries which reflects the international importance of this topic. A slight majority (53%, n = 32) of the studies were from North America. In the studies, researchers utilized case–control, cross-sectional, longitudinal, interventional and qualitative designs. No randomized controlled trials were identified. Researchers often used longitudinal study designs (62%, n = 37). Both case–control and interventional designs were rare. Four teams used qualitative methods. Approximately half of the studies were multisite. The majority (66%, n = 37) pertained to patient quality and the remainder of the studies pertained to the employees (See supporting information Table S3 in the online version of the article in Wiley Online Library).

Definition of off-shifts

All researchers identified whether an off-shift occurred at night and/or on the weekend. Off-shifts were also defined as ‘after hours’, ‘off-hours’, ‘non-office hours’ and ‘off-peak hours’. There were inconsistent definitions. For example, in one study ‘nights’ began at 1800 and in another study, ‘nights’ began at 1701 (Morales et al. 2003, Pilcher et al. 2007). Although researchers consistently defined ‘weekends’ as Saturday and Sunday, they disagreed on the exact time when the weekend began. In the quality outcome studies, the exact times of the off-shift were often provided. Conversely, employee outcome or qualitative methods did not clearly define the exact time of the off-shift.

Quality outcomes studies

There were 37 studies that examined patient quality outcomes. These outcomes included mortality, length of stay, frequency of procedures and treatment delays. Twenty-two studies examined the association between time of admission and/or discharge and patient outcomes. Eight groups of researchers studied the time of birth as the independent variable. Five studies examined the time of procedures and patient complications on off-shifts and two studies examined the association between nighttime nurse staffing and outcomes.

Relationship between time of admission and/or discharge and quality outcomes

The majority (85%, n = 18) of researchers examining relationships between time of admission and/or discharge and quality outcomes focused on weekends as the off-shift variable (Table 1). Although the hospital settings varied, 63% of the researchers examined patients in intensive care units (ICUs). There were three studies that examined patients discharged from ICUs. All study designs were longitudinal. The sample sizes in these studies varied (range from 611–3,789,917 patients). There was also a variety of patient populations included. A majority (90%, n = 20) of the researchers sampled adult patients, yet medical specialty differed including nephrology (James et al. 2010), neurology, (Saposnik et al. 2007) cardiology, (Kostis et al. 2007) and burn patients (Taira et al. 2009). Two studies sampled neonates and/or children (Hixson et al. 2005, Abdel-Latif et al. 2006). Only five studies occurred in a single site (Morales et al. 2003, Hixson et al. 2005, Arabi et al. 2006, Barba et al. 2006, Sheu et al. 2007).

Table 1.

Studies examining time of admission and/or discharge and patient outcomes.

| Author(s) & year, definition of off-shift | Setting, multisite (no. sites), patient sample size | Outcome(s) | Poor quality outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nights | |||

| Pilcher et al. (2007) ‘After hours’ 1800–0559 | ICUs, Y (40), 84,928 | Mortality and ICU readmission rate | Y |

| Morales et al. (2003) Night: 1701–0659 | Single ICU, N, 6,034 | Mortality, ICU LOS | N |

| Weekends | |||

| James et al. (2010)* Sat and Sun | Non-federal hospitals, Y (~1000), 214,962 | Mortality for acute kidney injury patients | Y |

| Schilling et al. (2010)* Sat and Sun | Hospitals, Y (39), 166,920 | Mortality | Y |

| Saposnik et al. (2007) 0000 Sat–2259 Sun | Morbidity Database, Y (606) 26,676 | 7-day mortality from stroke | Y |

| Kostis et al. (2007) Sat and Sun | MI Data System, Y (all New Jersey hospitals), 231,164 | 30-day mortality from myocardial infarction, LOS, use of invasive cardiac procedures | Y |

| Barba et al. (2006) 0000 Sat–2259 Sun | Acute hospitals, N, 359,993 | Mortality (within 48 hours) | Y |

| Cram et al. (2004)† 0000 Sat–2259 Sun | Acute hospitals, Y (all California hospitals) 641,860 | Mortality | Y |

| Ensminger et al. (2004) 1700 Fri–0700 Mon | ICUs, Y (2), 29,084 | Mortality | Mixed |

| Barnett et al. (2002) 0001 Sat–0001 Mon | ICUs, Y (28), 156,136 | Mortality, ICU LOS | Y |

| Bell and Redelmeier (2001) 0001 Sat–0001 Mon | Acute care hospitals, Y (all Ontario hospitals), 3,789,917 | Mortality | Y |

| Nights and weekends | |||

| Carr et al. (2011)§ Weekdays: 0900–1759 Mon–Fri Weeknights: 1800–0859 Mon–Fri Weekends: 1800 Fri–0859 Mon | Trauma facilities, Y (32), 90,461 | Mortality and secondary outcomes ICU LOS, hospital LOS and a delay longer than 2 hours to treatment by laparotomy or craniotomy | N |

| Laupland (2010)‡ ‘After hours’ Sat Sun daily 1800–0759 ‘Regular hours’ 0800–1759 Mon–Fri | Acute care hospitals, Y (4), 7722 | Mortality for community onset bloodstream infections patients | N |

| Taira et al. (2009)‡ ‘Off-hours’ 1800–0600 | Trauma facilities, Y (700) 25, 572 | Mortality and LOS for burn patients | N |

| Laupland et al. (2008)§ Night: 1800–0559 Weekend: 0001–Sat 2259 Sun | ICUs, Y (4), 20,446 | Mortality | Mixed |

| Sheu et al. (2007)‡ ‘Non-office hours’ 1800–0800 on weekday and all times on weekends | Single ICU, N, 611 | Mortality, LOS, ventilator-free days | N |

| Luyt et al. (2007)‡ ‘Off-hours’ 1830 to 0829, Weekend: 1300 Sat–0829, Mon, holidays: 0830–0829 | ICUS, Y (23), 51,643 | Mortality | N |

| Abdel-Latif et al. (2006) ‘After hours’ and holidays 1801–0759 | Neonatal ICUs, Y (10), 8654 | Mortality within 7 days & major morbidity of infants < 32 weeks | N |

| Arabi et al. (2006)§ Night: 1800 Sat 0759–Tues Weekend: 1800 Wed–0759 Sat | Single ICU, N, 2093 | Mortality, ICU LOS, ventilator-free days | N |

| Hixson et al. (2005)§ Eve: 1900–0700 Weekend: Sat and Sun | Single Paediatric ICU, N, 5968 | Mortality | N |

| Wunsch et al. (2004)§ Eve: 1800–2359, Night: 0000–0759 Weekend: Sat and Sun | ICUs, Y (102), 56,250 | Mortality | Mixed |

| Uusaro et al. (2003)‡ ‘Out of office hours’ 1601–0759 Weekend: 1600 Fri–2359 Sun | ICUs, Y (18), 23,134 | Mortality | Mixed |

Y, yes; N, no; ICU, intensive care unit; LOS, length of stay; MI, myocardial infarction.

Study also examined nurse staffing, seasonal influenza and hospital occupancy.

Study also examined hospital teaching status.

Analysed nights and weekends together.

Analysed nights and weekends separately.

In these 22 studies, all the researchers examined mortality as one of the outcomes. Most of the researchers (86%, n = 19) defined mortality as in-hospital mortality. However, other definitions of mortality were used. For example, Saposnik et al. (2007) sampled stroke patients and defined mortality as death 7-day from stroke onset whether it occurred in the hospital or not. A strength of many these studies is the use of multivariate logistic regression controlling for the following confounders: age, sex, severity of illness, medical complications and treatment facility.

In the nine studies that defined off-shifts as weekend-only, the results were mostly consistent and researchers found that patients were more likely to die if they were admitted on weekends as compared to during the week (Bell & Redelmeier 2001, Barnett et al. 2002, Cram et al. 2004, Ensminger et al. 2004, Barba et al. 2006, Kostis et al. 2007, Saposnik et al. 2007, James et al. 2010, Schilling et al. 2010). While Ensminger et al. (2004) found that patients admitted to a surgical ICU on weekends were more likely to die; this effect was not found for medical ICU patients. The results were also mixed when off-shifts was defined as nights exclusively; one group of researchers found that patients were more likely to die if they were admitted at night (Pilcher et al. 2007) and the other did not find this effect (Morales et al. 2003).

In 11 studies where researchers examined nights and weekends, both the methods of analyses and the results varied. Among these studies, 45% (n = 5) of researchers analysed nights and weekends together, another 45% (n = 5) analysed them separately and one group performed their analyses together and separately. When nights and weekends were analysed together, researchers did not find that patients who were admitted on off-shifts had higher mortality (Abdel-Latif et al. 2006, Luyt et al. 2007, Sheu et al. 2007, Taira et al. 2009, Laupland 2010). For example, Carr et al. (2011) found that patients presenting to trauma centres at night were not likely to die or have a delay in procedures compared with patients presenting during the day. In addition, patients presenting on weekends were less likely to die than patients presenting during weekdays (IRR = 0·89; 95% CI 0·81–0·97). Laupland (2010) found that admission with community onset bloodstream infection during after hours as compared to regular hours (614/4867 vs. 268/2056; P = 0·6) did not increase the risk of mortality. These results were also similar for two of the studies that analysed nights and weekends separately, that is, in these two studies neither nights nor weekends were associated with mortality (Hixson et al. 2005, Arabi et al. 2006).

Patient length of stay was conceptualized as a quality outcome in seven studies (Barnett et al. 2002, Morales et al. 2003, Arabi et al. 2006, Kostis et al. 2007, Sheu et al. 2007, Taira et al. 2009, Carr et al. 2011). The setting in four of these seven studies was an ICU (Barnett et al. 2002, Morales et al. 2003, Arabi et al. 2006, Sheu et al. 2007) and in only one study was there a statistically significant difference in intensive care length of stay for weekend or Friday admissions compared with midweek admissions (Barnett et al. 2002). However, the study by Barnett et al. was multi-site and the other three studies occurred in a single setting and had smaller sample sizes. Therefore, statistical power may have been an issue.

Relationship between time of birth and quality outcomes

Eight research teams examined the association between time of birth and neonatal outcomes (Table 2). A majority (75%, n = 6) of the researchers studied outcomes of those babies born at night compared to days (Stewart et al. 1998, Luo & Karlberg 2001, Gould et al. 2005, Urato et al. 2006, Badr et al. 2007, Caughey et al. 2008). The sample sizes in these studies also varied (range 1015 to over 3 million babies). One study used a case–control design, whereas the other studies were longitudinal. Most researchers used database registries (Stewart et al. 1998, Luo & Karlberg 2001, Stephansson et al. 2003, Gould et al. 2005, Urato et al. 2006, Bell et al. 2010). Infant mortality was the quality outcome in all studies, but other neonatal outcomes including short-term morbidity and neurodevelopmental outcomes were included. All the researchers used logistic regression and controlled for confounders, which included maternal age, birth weight, prenatal care, number of pregnancies, race and delivery by midwife.

Table 2.

Studies examining the association between time of birth on patient outcomes.

| Author(s) and year, definition of off-shift | Multisite (no. sites), patient sample size | Outcome(s) | Poor quality outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nights | |||

| Caughey et al. (2008), Evening: 1800–0001, Night: 0001–0700 | N, 34,046 | Mortality and Apgar scores | N |

| Badr et al. (2007), Night: 2300–0700 | Y (4), 5152 | Mortality, asphyxia, neonatal morbidity | Y |

| Urato et al. (2006), Night: 2301–0759 | Registry, 80 cases, 999 controls | Mortality | Y |

| Gould et al. (2005), Early night: 1900–0059 Late night: 0100–0659 | Registry, 3,363,157 | Mortality | Y |

| Luo and Karlberg (2001), Night: 2100–0700 | Registry, 2,102,324 | Mortality | Y |

| Stewart et al. (1998), Night: 2100–0859 | Registry, 1015 | Mortality | Y |

| Nights and weekends | |||

| Bell et al. (2010)*, Early night: 1701–2259, Late night: 0000–0759 Weekend: Sat and Sun | Registry, 11,137 | Mortality within 7 and 28 days, short-term morbidity and neurodevelopmental outcomes of low birth weight infants | N |

| Stephansson et al. (2003)*, Night: 2000–0759, Weekend: Sat and Sun | Registry, 694,888 | Mortality | Y |

Y, yes; N, no.

Analysed nights and weekends separately.

In two studies, researchers did not find an association between time of birth and mortality. In these studies, both Bell et al. (2010) and Caughey et al. (2008) compared neonatal outcomes by three time periods – day, evening and night. Bell et al. (2010) conducted their analyses at institutions that had resident duty-hour restrictions and concluded that restrictions on resident duty-hours reduced resident fatigue and increased supervisory surveillance. All the other results were mostly consistent and the researchers found that babies born at night were more likely to die than those born during the day (Stewart et al. 1998, Luo & Karlberg 2001, Stephansson et al. 2003, Gould et al. 2005, Urato et al. 2006, Badr et al. 2007).

Relationship between time of procedures and patient complications on off-shifts

Five groups of researchers studied treatment delays and/or complications on off-shifts (Table 3). Authors provided clear definitions and the sample sizes were large (range over 1000 to almost 5 million patients). Cardiac patients were sampled in four of the five studies (Sadeghi et al. 2004, Becker 2007, Peberdy et al. 2008, Uyarel et al. 2009). The other group examined complication rates of eight patient safety indicators including postoperative haemorrhage, newborn trauma, vaginal deliveries and obstetric trauma during caesarean sections (Bendavid et al. 2007). Of the five groups, three found that patients were more likely to have delays in treatment and/or develop complications on off-shifts as compared to more regular hours (Becker 2007, Bendavid et al. 2007, Peberdy et al. 2008).

Table 3.

Studies examining time of procedures and patient complications on off-shifts.

| Author(s) & year, definition of off-shift | Multisite (no. sites) Patient Sample Size | Outcome(s) | Poor quality outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uyarel et al. (2009), Night: 1800–0800 | N, 2,644 | Angioplasty outcomes, cardiovascular mortality, LOS | N |

| Peberdy et al. (2008)*, Night: 2200–0659 Weekend: 2200 Fri–0659 Mon | Y (507), 86,748 | Survival from in-hospital cardiac arrest | Y |

| Becker (2007), Weekend: Sat and Sun | Registry, 922,074 | Angioplasty, cardiac catheterization, bypass rates, mortality | Y |

| Bendavid et al. (2007), Weekend: Sat and Sun | Registry, 4,967,114 | Complications, birth trauma | Y |

| Sadeghi et al. (2004)†, ‘Off-peak hours’ 2000–0800 | Y (76), 1047 | Treatment delays, thrombolysis, mortality | N |

Y, yes; N, no; LOS, length of stay.

Analysed nights and weekends separately and together.

Analysed nights and weekends together.

Night nurse staffing and quality outcomes

There were two studies that examined the association of night nurse staffing and hospital mortality. Secondary outcomes included patient length of stay and total hospital cost (Amaravadi et al. 2000, Dimick et al. 2001). These researchers studied the effect on patient outcomes when night nurses cared for one or two patients as compared to three or more patients in ICUs (Amaravadi et al. 2000, Dimick et al. 2001). In both studies, the researchers found no important difference in mortality, but found that length of stay and cost increased when night nurse-to-patient ratio was greater than 1:2 (Amaravadi et al. 2000, Dimick et al. 2001).

Employee outcomes studies

There were 19 studies that examined employee outcomes (Table 4). Off-shift was defined as nights in (n = 7) or nights with rotation (n = 12). In the studies where researchers focused on nights, a variety of healthcare workers were sampled. The sample sizes for these seven studies ranged from 38–7717 participants. Most (n = 5) used cross-sectional designs. In the study with the largest sample, researchers longitudinally examined 7717 workers’ compensation claims in Oregon and found that nurses who worked at night had more injuries (Horwitz & McCall 2004). Only two studies occurred in a single setting (Arora et al. 2006, West et al. 2007).

Table 4.

Studies examining off-shifts and healthcare employee outcomes.

| Author(s) and year | Sample, sample size, multisite (no. sites) | Outcome(s) | Poor employee outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nights | |||

| Barnes-Farrell et al. (2008) | Healthcare workers, 1014, Y* | Work-family conflict, physical and mental well-being | Y |

| West et al. (2007) | Nurses, 150, N | Chronic fatigue, sleep disturbances, social and domestic stressors, job dissatisfaction, burnout | Mixed |

| Arora et al. (2006) | Medical Residents, 38, N | Fatigue, on-call sleep, post-call fatigue | Y |

| Newey and Hood (2004) | Nurses and their partners, 59, Y (2) | Fatigue, health, stress, social factors | Mixed |

| Horwitz and McCall (2004) | Healthcare workers, 7717, Registry | Injury | Y |

| Ruggiero (2003) | Nurses, 142, Y† | Chronic fatigue, sleep quality, depression, anxiety | Y |

| Peterson (1985) | Nurses, 272, Y (30) | Physician/nurse relations, role integration, group tension, job dissatisfaction | N |

| Nights with rotation | |||

| Burch et al. (2009) | Healthcare workers, 376, N | Sleep characteristics, attitude, health symptoms, coping strategies, social and lifestyle factors | Mixed |

| Korompeli et al. (2009) | Nurses, 32, N | Sleep, health, coping, circadian type, job satisfaction, anxiety, personality inventory, social and domestic factors | Y |

| Admi et al. (2008) | Nurses, 739, N | Sleep disorders, medical issues, clinical errors, adverse events | N |

| Camerino et al. (2008) | Nurses, 7516, Y‡ | Work ability, sleep and satisfaction | Mixed |

| Leff et al. (2008) | Medical Residents, 21, N | Sleep, surgical skill performance, clinical errors | Y |

| Samaha et al. (2007) | Nurses, 121, Y (3) | Fatigue, anxiety, mood | Mixed |

| Choobineh et al. (2006) | Healthcare workers, 432, Y(12) | Insomnia, hypnotic drug use, adverse effects on own, family and social life, health, job satisfaction | Y |

| Costa et al. (2004) | Healthcare workers, 21,505, Y§ | Health and well-being from flexible working hours | Y |

| Geiger-Brown et al. (2004) | Nursing assistants, 539, Y (49) | Depression | Y |

| Barton (1994) | Nurses, 587, Y (28) | Fatigue, sleep disturbances, health anxiety, job satisfaction, social, domestic, non-domestic disruption | N |

| Jamal and Baba (1992) | Nurses, 585, Y (8) | Role ambiguity, role overload, job stress and satisfaction, organizational commitment, social support, turnover intention, commitment to nursing | Y |

| Gold et al. (1992) | Nurses, 635, N | Fatigue, sleep quality, medications and alcohol for sleep, medication errors, medication near misses, car accidents | Y |

All study designs were cross-sectional except for Arora, Horwitz & McCall and Leff.

Y, yes; N, no.

Convenience sample of healthcare workers from four countries; USA, Australia, Croatia and Brazil.

Random sample of 68,000 members of the American Association of Critical Care Nurses.

Nurses worked in state-owned and private hospitals in Belgium, Germany, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland and Slovakia.

Workers representing 15 European countries as part of the Third European Union Survey on Working Conditions.

Twelve groups of researchers examined the association between nights with rotation and multiple employee outcomes (Gold et al. 1992, Jamal & Baba 1992, Barton 1994, Costa et al. 2004, Geiger-Brown et al. 2004, Choobineh et al. 2006, Samaha et al. 2007, Admi et al. 2008, Camerino et al. 2008, Leff et al. 2008, Burch et al. 2009, Korompeli et al. 2009). Similar to the ‘night-only’ studies, researchers sampled a variety of healthcare workers. Most investigations were cross-sectional, however, one group also used an interventional strategy to evaluate surgical skills after a resident rotates to night shift (Leff et al. 2008). Half of these studies were multisite.

Fatigue and sleep disturbances

In both the nights and nights with rotation studies, most groups of researchers (n = 13) examined fatigue and sleep disturbances as an outcome (Gold et al. 1992, Barton 1994, Ruggiero 2003, Newey & Hood 2004, Arora et al. 2006, Choobineh et al. 2006, Samaha et al. 2007, West et al. 2007, Admi et al. 2008, Camerino et al. 2008, Leff et al. 2008, Burch et al. 2009, Korompeli et al. 2009). Ruggiero (2003) found that providers that worked at night had less quality sleep than those who worked during the day. Arora et al. (2006) tested a sleep intervention and found an important effect that sleep efficiency improved when an intern napped. Four groups of researchers found statistically significant associations between night rotation and poor sleep (Gold et al. 1992, Choobineh et al. 2006, Leff et al. 2008, Korompeli et al. 2009). In addition, one researcher found that nurses had significantly more sleep difficulties when they rotated than did permanent night shift nurses (Barton 1994).

Health and well-being

Some of these researchers (n = 7) also examined health outcomes including well-being (Peterson 1985, Ruggiero 2003, Costa et al. 2004, Geiger-Brown et al. 2004, Horwitz & McCall 2004, Newey & Hood 2004, Barnes-Farrell et al. 2008). These groups found important associations between night work and lower well-being. Specifically, Ruggiero (2003) found that permanent night nurses had significantly more depression than day nurses. In addition, in 539 nursing assistants, researchers found that assistants who rotated to work at night were more likely to meet the criteria for a depressive disorder (Geiger-Brown et al. 2004). In addition, researchers found that more company-flexibility, (e.g. variability) was associated with decreased health and well-being (Costa et al. 2004).

Job satisfaction

Job satisfaction was also examined in six studies with mixed results (Peterson 1985, Jamal & Baba 1992, Barton 1994, Choobineh et al. 2006, West et al. 2007, Korompeli et al. 2009). For example, one researcher found that the shift on which a nurse usually worked was not associated with poor outcomes (i.e. tension or job dissatisfaction) (Peterson 1985). Korompeli et al. (2009) did find an association between night work and poor job satisfaction; however, only 32 nurses were studied. Barton (1994) reported that permanent night nurses preferred to work at night rather than rotating to work at night. Camerino et al. (2008) found that work schedule did not significantly predict changes in work ability. However, these researchers found that sleep, satisfaction and rewards were significantly lower in rotating nurses as compared to day workers and even permanent night nurses (Camerino et al. 2008).

Errors

Three groups examined clinical errors as an employee outcome (Gold et al. 1992, Admi et al. 2008, Leff et al. 2008). Two of the three teams found statistically significant associations between employees who worked nights and rotated and the error rate (Gold et al. 1992, Leff et al. 2008). For example, Leff et al. (2008) found that residents who rotated took significantly longer (P = 0·002) and made more errors (P = 0·025) on a surgical simulator task following their first night shift compared with their pre-nights baseline performance. In addition, Gold et al. (1992) found that nurses who rotated were almost two times more likely to report an accident and/or errors compared to nurses who worked day and/or evenings (OR 1·97, 95% CI 1·07–3·63).

Qualitative method studies

Four groups of researchers used qualitative methods to understand off-shift nursing work (Campbell et al. 2008, Hamilton et al. 2007, Nilsson et al. 2008, Nasrabadi et al. 2009). In these studies, the research questions were clear and qualitative methodology was appropriate. These researchers inductively examined nurses’ perceptions about quality outcomes (e.g. neonatal mortality) and employee outcomes (e.g. fatigue). Different qualitative data collection methods were used including open-ended interviews, semi-structured interviews and focus groups. The purposeful sampling procedures were clearly described in all studies. Three groups of researchers explored nurses’ perceptions of working at night (Campbell et al. 2008, Nilsson et al. 2008, Nasrabadi et al. 2009). The other group's aim was to identify differences between weekend and weekday nurse work environments in the labour and delivery department (Hamilton et al. 2007). In all these studies, how the researchers collected and qualitatively analysed their data was appropriate to address their research questions.

In two studies, decreased staffing themes on off-shifts emerged. Nilsson et al. (2008) found that night work assignments were similar to those in the daytime, but are carried out by fewer staff. Hamilton et al. (2007) found that the reduced number of clinicians, supervisors and patients made it possible to give better care, although others felt there were lapses in patient safety. The other two studies found that there were learning situations at night; in addition, night nurses sometimes demonstrated more independent thinking due to decreased resources available (Campbell et al. 2008, Nasrabadi et al. 2009). These interpretations were supported by sufficient evidence that the researchers analysed.

Discussion

Hospitals will always function 24-hour-a-day, 7-day-a week. Therefore, it is important to understand if in the current organization of the healthcare system off-shifts are associated with poor patient and employee outcomes. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review examining relationships between off-shifts and outcomes. In an attempt to be comprehensive, studies were not excluded based on design. Although the findings were mixed, weekends were associated with poor quality outcomes even among diverse patient populations. At night, there was minimal evidence that quality outcomes suffered, except in the labour and delivery room. When nights and weekends were analysed together, the evidence was also mixed. Since weekends were associated with poor patient outcomes, it is possible that grouping nights and weekends together may mask the negative effect of the weekend.

In the employee outcomes studies, there was statistically significant evidence that providers who work at night and rotate to work at night were more likely to have poor outcomes (e.g. fatigue, decreased mental well-being and job dissatisfaction). However, from this review, it cannot be determined if those poor employee outcomes impacted quality care. There were only three studies that evaluated errors in addition to employee outcomes and the results from those studies were mixed.

Some of the studies in this review are publications based on work of the Working Time Society (2011). This Society is committed to improving, health, safety and well-being of shift workers in Europe and around the world and researchers in this Society have published work about both short and long-term health effects of shift workers (http://www.work-ingtime.org). Some studies that were included in this review include work from journals such as Applied Ergonomics, Chronobiology International and Occupational Medicine. These studies demonstrate the interdisciplinary interest in further understanding shift work and employee outcomes.

Limitations and strengths of the evidence

Employee outcome studies had generally smaller sample sizes than the quality outcome studies and researchers often used cross-sectional designs based on self-report. An employee may not report fatigue if she/he has adapted to and chose to work at night. Having control over one's schedule may contribute to why researchers found higher rates of fatigue, but did not find any differences in attitude or job satisfaction at night as compared to during the day (West et al. 2007).

The majority of the studies examining quality outcomes were longitudinal, which is a stronger research design than the cross-sectional studies. However, there were also weaknesses in the investigations studying patient outcomes. For example, the researchers often used administrative databases, which have inherent limitations. First, although the majority of researchers implemented quality control measures for data abstraction, there may have been errors in this process and/or the data may be incorrectly coded in the database. In addition, using existing databases for analysis, there may be unmeasured confounders.

Another limitation of the quality outcome studies is that researchers only studied the relationship between time of admission/discharge and mortality. Admission and discharge time may be the easiest to operationalize in large databases. However, this does not inform the processes of care. Researchers often acknowledged this limitation and commented that staffing levels or decreased resources on off-shifts may impact quality care. A comprehensive examination staffing and characteristics of the off-shift staff compared to regular hours may further assist in understanding quality on off-shifts.

Patient mortality was the most common quality outcome studied. This is not surprising since mortality is clearly important and easily identified in the datasets. It is also a common measure of quality care and has been endorsed by the National Quality Forum (2004). Patient length of stay in the hospital was also infrequently examined. In only five studies identified rates of procedures and complications on the off-shifts were examined. This was surprising given the increased international interest in patient safety and nursing sensitive outcomes (Clarke & Aiken 2008, Chaboyer et al. 2010). We encourage future researchers to study these other important quality outcomes.

Although the majority of studies that compared quality of care provided on weekends to mid-week found outcomes to be less desirable on the weekends, the overall results of off-shifts and quality outcomes were mixed. An explanation may be from the diversity of patient populations. Although known confounders were often controlled for, underlying patient differences may have contributed to the mixed results. Also, many studies where researchers did not find an association between off-shifts and quality outcomes occurred in a single institution. In these single site studies, a hospital may have similar staffing and/or education level of healthcare providers and/or continuous on-site coverage by qualified intensivists on both regular and off-shifts or sample sizes and a lack of statistical power may have contributed to the lack of differences. Overall, multi-site studies were stronger in design and increased the generalizability of results.

There was inconsistency on how off-shifts were defined and how researchers analysed the off-shifts. Some researchers who studied both nights and weekends, conducted their analyses together, as opposed to performing separate analyses of nights and separate analyses of weekends. Again, this posed challenges when synthesizing the results.

Limitations and strengths of the review

There are strengths and limitations to this review. The search was conducted over several months and although every effort was made to be comprehensive, it is still possible that some studies were missed. Publication bias may be present; however, we did find studies that found no differences diminishing our concern about this potential bias. Only studies published in English were included in the review. Study appraisal was conducted using a well developed instrument; however, due to the inconsistencies of definitions, study designs and outcomes there was no meta-analysis conducted. Finally, due to the volume of studies included in the review, quality appraisal was conducted by the first author and supervised by the senior authors.

Conclusion

The overall conclusion of this systematic review is that a slight majority of the researchers found that off-shifts may be associated with poor patient and employee outcomes. Specifically, patients admitted to hospitals on weekends are more likely to die and not receive necessary procedures. There was a small effect for patients admitted at night. Specifically, babies who were born at night were more likely to die. Employees who work at night are more likely to suffer from fatigue as compared with employees who work during the day. Furthermore, when employees rotate to cover night shifts, they are also more likely to suffer from fatigue. However, there is minimal evidence that poor employee outcomes may negatively impact quality care. Differences in the evidence exist between nights and weekends, future research should examine these types of off-shifts more closely.

Nursing implications

It is unclear why patient outcomes are worse on off-shifts, specifically on weekends, than during normal day hours. Decreased resources and staffing on off-shifts may impact patient outcomes; however, there is lack of research examining these associations. Future research should also include studying the off-shift workforce, which may differ from the day workforce and the impact on patient outcomes. The nursing work at night may differ than during the day. In addition, training and continuing education programmes may only be offered to nurses during the day limiting the ability for permanent night nurses to further their clinical education; for example, night nurses may not be able to attend clinical educational programmes that are offered during the day due to conflict with other responsibilities (Stewart et al. 2010). Without access to continuing education programmes, the night nursing workforce may be less adept at detecting changes in patient's conditions which may result in worse patient outcomes. Therefore, there is a need to increase educational opportunities for permanent night nurses.

Rotating nurses to ensure adequate clinical skills does not seem sensible given that there is little evidence suggesting poor quality of care on these shifts. Furthermore, there is evidence supporting the notion that nurses who work at night and rotate to work at night have worse physical and mental ailments than nurses who work during the day. If possible, nurse administrators should limit the shift rotation of employees and encourage night employees to self-schedule to provide for consistency. Self-scheduling may a decrease stress and improve the well-being and job satisfaction of night nurses. It may also behove administrators to determine which nurses are willing and prefer working at night rather than requiring nurses to take a night position.

Supplementary Material

What is already known about this topic.

Hospitals often have decreased resources available at night and during the weekend as compared to during the day.

Healthcare providers deliver 24-hour, 7-day-a-week care requiring some providers to work at night and on weekends.

To ensure sufficient coverage for patients, some providers who often work during the day are required to rotate to work at night.

What this paper adds

The majority of the articles reviewed were longitudinal studies that examined patient mortality (22 studies). Specifically, patients admitted to hospitals on weekends were more likely to die than patients admitted during the week.

Other longitudinal studies included in this review examined time of birth and neonatal mortality (eight studies). A majority of those studies found that babies who were born at night were more likely to die than babies born during the day.

There were 19 studies that examined healthcare provider outcomes. The majority of these studies used cross-sectional designs and found that night providers and those that rotated to work at night suffered from more fatigue, more sleep disturbances and less well-being than providers who worked during the day.

Implications for practice and/or policy

Decreased resources on nights and weekends may impact patient safety, however, there is lack of research examining why these associations occur. Future research should include studying the off-shift nursing workforce which may differ from the day workforce.

There should be increased education and training opportunities available for permanent night nurses to further their clinical education.

Administrators should consider minimizing the rotation of day nurses to work at nights and encourage night nurses to self-schedule to decrease fatigue, sleep disturbances and improve well-being.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This project was supported by grant number 053420 from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, R36HS018216 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, IIR 09-362 from the Veterans’ Affairs and from Sigma Theta Tau Alpha Zeta Chapter. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of these funding agencies. Additionally, the corresponding author acknowledges her current postdoctoral fellowship from the National Institute of Nursing Research training grant ‘Advanced Training in Nursing Outcomes Research’ (T32-NR-007104, Linda Aiken, PI).

Footnotes

Author contributions

- substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data;

- drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content.

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest has been declared by the authors.

Supporting Information Online

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Table S1. Quality assessment criteria.

Table S2. Quality appraisal outcome for each study.

Table S3. Characteristics of 60 studies in the systematic review.

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supported by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

Contributor Information

Pamela B. de Cordova, Center for Health Outcomes and Policy Research, School of Nursing, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

Ciaran S. Phibbs, Health Economics Resource Center, VA Palo Alto Healthcare System, Menlo Park, California, USA.

Ann P. Bartel, Columbia Business School, New York, New York, USA.

Patricia W. Stone, Columbia University School of Nursing, New York, New York, USA.

References

- Abdel-Latif ME, Bajuk B, Oei J, Lui K. Mortality and morbidities among very premature infants admitted after hours in an Australian neonatal intensive care unit network. Pediatrics. 2006;117(5):1632–1639. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aboelela SW, Stone PW, Larson EL. Effectiveness of bundled behavioural interventions to control healthcare-associated infections: a systematic review of the literature. The Journal of Hospital Infection. 2007;66(2):101–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2006.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Admi H, Tzischinsky O, Epstein R, Herer P, Lavie P. Shift work in nursing: is it really a risk factor for nurses’ health and patients’ safety? Nursing Economics. 2008;26(4):250–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akerstedt T. Shift work and disturbed sleep/wakefulness. Occupational Medicine. 2003;53:89–94. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqg046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaravadi RK, Dimick JB, Pronovost PJ, Lipsett PA. ICU nurse-to-patient ratio is associated with complications and resource use after esophagectomy. Intensive Care Medicine. 2000;26:1857–1862. doi: 10.1007/s001340000720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arabi Y, Alshimemeri A, Taher S. Weekend and week-night admissions have the same outcome of weekday admissions to an intensive care unit with onsite intensivist coverage. Critical Care Medicine. 2006;34(3):605–611. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000203947.60552.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora V, Dunphy C, Chang VY, Ahmad F, Humphrey HJ, Meltzer D. The effects of on-duty napping on intern sleep time and fatigue. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2006;144(11):792–798. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-11-200606060-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badr LK, Abdallah B, Balian S, Tamin H, Hawari M. The chasm in neonatal outcomes in relation to time of birth in Lebanon. Neonatal Network. 2007;26(2):97–102. doi: 10.1891/0730-0832.26.2.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barba R, Losa JE, Velasco M, Guijarro C, Garcia de Casasola G, Zapatero A. Mortality among adult patients admitted to the hospital on weekends. European Journal of Internal Medicine. 2006;17(5):322–324. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes-Farrell JL, Davies-Schrils K, McGonagle A, Walsh B, Di Milia L, Fischer FM, Hobbs BB, Kaliterna L, Tepas D. What aspects of shiftwork influence off-shift well-being of healthcare workers? Applied Ergonomics. 2008;39:589–596. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2008.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett MJ, Kaboli PJ, Sirio CA, Rosenthal GE. Day of the week of the intensive care admission and patient outcomes: a multisite regional evaluation. Medical Care. 2002;40(6):530–539. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200206000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton J. Choosing to work at night: a moderating influence of individual tolerance to shift work. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1994;79(3):449–454. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.79.3.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker D. Do hospitals provider lower quality care on weekends. Health Services Research. 2007;42(4):1589–1612. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00663.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell CM, Redelmeier DA. Mortality among patient admitted to hospitals on weekends as compared to weekdays. New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;345(9):663–668. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa003376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell EF, Hansen NI, Morriss FH, Stoll BJ, Namasivayam A, Gould JB, Laptook MC, Walsh WA, Carlo WA, Shankaran S, Das A, Higgins RD. Impact of timing of birth and resident duty-hour restrictions on outcomes for small preterm infants. Pediatrics. 2010;126(2):222–231. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendavid E, Kaganova Y, Needleman J, Gruenberg L, Weissman JS. Complication rates on weekends and weekdays in US hospitals. The American Journal of Medicine. 2007;120(5):422–428. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.05.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger A, Hobbs B. Impact of shift work on the health and safety of nurses and patients. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2006;10(4):465–470. doi: 10.1188/06.CJON.465-471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burch JB, Tom J, Criswel L, Leo E, Ogoussan K. Shiftwork impacts and adaptation among health care workers. Occupational Medicine. 2009;59:159–166. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqp015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camerino D, Conway PM, Sartori S, Campanini P, Estryn-Behar M, van der Heijden BIJM, Costa G. Factors affecting work ability in day and shift-working nurses. Chronobiology International. 2008;25(2 & 3):425–442. doi: 10.1080/07420520802118236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell A, Nilsson K, Pilhammar AE. Night duty as an opportunity for learning. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2008;62:346–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr BC, Reilly PM, Schwab W, Branas CC, Geiger J, Wiebe DJ. Weekend and night outcomes in a statewide trauma center. Archives of Surgery. 2011;146(7):810–815. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caughey AB, Urato AC, Lee KA, Thiet M, Washington E, Laros RK. Time of delivery and neonatal morbidity and mortality. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2008;199(5):496.e491–496.e495. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaboyer W, Johnson J, Hardy L, Gehrke T, Panuwatwanich K. Transforming care strategies and nursing-sensitive patient outcomes. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2010;66(5):1111–1119. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choobineh A, Rajaeefard A, Neghab M. Problems related to shiftwork for health care workers at Shirza University of Medical Sciences. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal. 2006;12(3/4):340–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke SP, Aiken LH. An international hospital outcomes research agenda focused on nursing: lessons from a decade of collaboration. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2008;17(24):3317–3323. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02638.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa G, Akerstedt T, Nachreiner F, Baltieri F, Carvalhais J, Folkard S, Dresen MF, Cadbois C, Gartner J, Sukalo HG, Kandolin I, Sartori S, Silverio J. Flexible working hours, health and well-being in Europe: some considerations from a SALTSA project. Chronobiology International. 2004;21(6):831–844. doi: 10.1081/cbi-200035935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cram P, Hillis SL, Barnett M, Rosentahal GE. Effects of weekend admission and hospital teaching status on in-hospital mortality. The American Journal of Medicine. 2004;117:151–157. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimick JB, Swoboda SM, Pronovost PJ, Lipsett PA. Effect of nurse-to-patient ratio in the intensive care unit on pulmonary complications and resource use after hepatectomy. American Journal of Critical Care. 2001;10(6):376–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon-Wood M, Shaw RL, Agarwal S, Smith JA. The problem of appraising qualitative research. Quality & Safety in Health Care. 2004;13:223–225. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2003.008714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ensminger SA, Morales IJ, Peters SG, Keegan MT, Finkielman JD, Lymp JF, et al. The hospital mortality of patients admitted to the ICU on weekends. Chest. 2004;126(4):1292–1298. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.4.1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger-Brown J, Muntaner C, Lipscomb J, Trinkoff A. Demanding work schedules and mental health in nursing assistants working in nursing homes. Work & Stress. 2004;18(4):292–304. [Google Scholar]

- Gold DR, Rogacz S, Bock N, Tosteson TD, Baum TM, Speizer FE, et al. Rotating shift work, sleep and accidents related to sleepiness in hospital nurses. American Journal of Public Health. 1992;82(7):1011–1014. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.7.1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould JB, Qin C, Chavez G. Time of birth and the risk of neonatal death. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2005;106(2):352–358. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000168627.33566.3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton P, Eschiti VS, Hernandez K, Neill D. Differences between weekend and weekday nurse work environments and patient outcomes: a focus group approach to model testing. Journal of Perinatal & Neonatal Nursing. 2007;21(4):331–341. doi: 10.1097/01.JPN.0000299791.54785.7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton P, Mathur S, Gemeinhardt G, Eschiti V, Campbell M. Expanding what we know about off-peak mortality in hospitals. Journal of Nursing Administration. 2010;40(3):124–128. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0b013e3181d0426e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hixson ED, Davis S, Morris S, Harrison AM. Do weekends or evenings matter in a pediatric intensive care unit? Pediatric Critical Care Medicine. 2005;6(5):523–530. doi: 10.1097/01.pcc.0000165564.01639.cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz IB, McCall BP. The impact of shift work on the risk and severity of injuries for hospital employees: an analysis using Oregon workers’ compensation data. Occupational Medicine. 2004;54(8):556–563. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqh093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamal M, Baba VV. Shiftwork and department-type related to job stress, work attitudes and behavioral intentions: a study of nurses. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 1992;13:449–464. [Google Scholar]

- James MT, Wald R, Bell CM, Tonelli M, Hemmelgarn BR, Waikar SS, Chertow GM. Weekend hospital admission, acute kidney injury and mortality. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2010;21:845–851. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009070682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korompeli A, Sourtzi P, Tzavara C, Velonakis E. Rotating shift-related changes in hormone levels in intensive care unit nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2009;65(6):1274–1282. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.04987.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostis WJ, Demissie K, Marcella SW, Sharo Y-H, Wilson AC, Moreyra AE. Weekend versus weekday admission and mortality from myocardial infarction. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;356(11):1099–1109. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laupland KB. Admission to hospital with community-onset bloodstream infection during the ‘after hours’ is not associated with an increased risk for death. Scandinavian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2010;42:862–865. doi: 10.3109/00365548.2010.501811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laupland KB, Shahpori R, Kirkpatrick AW, Stelfox HT. Hospital mortality among adults admitted to and discharged from intensive care on weekends and evenings. Journal of Critical Care. 2008;23:317–324. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leff DR, Aggarwal R, Rana M, Nakhjavani B, Purkayastha S, Khullar V, et al. Laparoscopic skills suffer on the first shift of sequential night shifts: program directors beware and residents prepare. Annals of Surgery. 2008;247(3):530–539. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181661a99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo ZC, Karlberg J. Timing of birth and infant and early neonatal mortality in Sweden 1973-95: longitudinal birth register study. BMJ. 2001;323:1–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7325.1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luyt C-E, Combes A, Aegerter P, Guidet B, Trouillet J-L, Gibert C, et al. Mortality among patients admitted to intensive care units during weekday day shifts compared with ‘off’ hours. Critical Care Medicine. 2007;35(1):3–11. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000249832.36518.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales IJ, Peters SG, Afessa B. Hospital mortality rate and length of stay in patients admitted at night to the intensive care unit. Critical Care Medicine. 2003;31(3):858–863. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000055378.31408.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasrabadi AN, Seif H, Latifi M, Rasoolzadeh N, Emami A. Night shift work experiences among Iranian nurses: a qualitative study. International Nursing Review. 2009;56:498–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2009.00747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Quality Forum . National Voluntary Consensus Standards for Nursing-Sensitive Care: An Initial Performance Measure Set. National Quality Forum; Washington, DC: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Newey CA, Hood BM. Determinants of shift-work adjustment for nursing staff: the critical experience of partners. Journal of Professional Nursing. 2004;20(3):187–195. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson K, Campbell A, Andersson EP. Night nursing – staff's working experiences. BMC Nursing. 2008;7(13):7–13. doi: 10.1186/1472-6955-7-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peberdy MA, Ornato JP, Larkin GL, Braithwaite RS, Kashner TM, Carey SM, et al. Survival from in-hospital cardiac arrest during nights and weekends. JAMA. 2008;299(7):785–792. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.7.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson MF. Attitudinal differences among work shifts: what do they reflect. Academy of Management Journal. 1985;28(3):723–732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilcher DV, Duke GJ, George C, Bailey MJ, Hart G. After-hours discharge from intensive care increase the risk of readmission and death. Anaesthesisa and Intensive Care. 2007;35(4):477–485. doi: 10.1177/0310057X0703500403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers AE, Hwang W, Scott LD, Aiken LH, Dinges DF. The working hours of hospital staff nurses and patient safety. Health Affairs (Millwood, Va.) 2004;23(4):202–212. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.4.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa RR, Colligan MJ. Plain Language About Shiftwork. US Department of Health and Human Services Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Cincinnati: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ruggiero JS. Correlates of fatigue in critical care nurses. Research in Nursing & Health. 2003;26(6):434–444. doi: 10.1002/nur.10106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghi HM, Grines CL, Chandra HR, Mehran R, Fahy M, Cox DA, et al. Magnitude and impact of treatment delays on weeknights and weekends in patients undergoing primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction (the CADILLAC Trial). American Journal of Cardiology. 2004;94:637–640. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samaha E, Lal S, Samaha N, Wyndham J. Psychological, lifestyle and coping contributors to chronic fatigue in shift-worker nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2007;59(3):221–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saposnik G, Baibergenova A, Bayer N, Hachinski V. Weekends: a dangerous time for having a stroke? Stroke. 2007;38:1211–1215. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000259622.78616.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilling PL, Campbell DA, Englesbe MJ, Davis MM. A comparison of in-hospital mortality risk conferred by high hospital occupancy, differences in nurse staffing levels, weekend admission and seasonal influenza. Medical Care. 2010;48(3):224–232. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181c162c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheu C-C, Tsai J-R, Hung J-Y, Yang C-J, Hung H-C, Chong I-W, et al. Admission time and outcomes of patients in an medical intensive care unit. Kaohsiung Journal of Medical Science. 2007;23(8):395–403. doi: 10.1016/S0257-5655(07)70003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephansson O, Dickman PW, Johansson AL, Kieler H, Cnattingius S. Time of birth and risk of intrapartum and early neonatal death. Epidemiology. 2003;14(2):218–222. doi: 10.1097/01.EDE.0000037975.55478.C7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart JH, Andrews J, Cartlidge PT. Numbers of deaths related to intrapartum asphyxia and timing of birth in all Wales perinatal survey. BMJ. 1998;316(7132):657–660. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7132.657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart C, Snyder K, Sullivan SC. Journal clubs on the night shift: a staff nurse initiative. Medsurg Nurse. 2010;19:305–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taira B, Meng H, Goodman M, Singer A. Does ‘off-hours’ admission affect burn patient outcome? Burns. 2009;35:1092–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2009.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- University of York [25 November 2010];Systematic Reviews: CRD's Guidance for Undertaking Reviews in Health Care. 2009 from http://www.york.ac.uk/inst/crd/report4.htm.

- Urato AC, Craigo SD, Chelmow D, O'Brien WF. The association between time of birth and fetal injury resulting in death. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2006;195(6):1521–1526. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.03.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uusaro A, Kari A, Ruokonen E. The effects of ICU admission and discharge times on mortality in Finland. Intensive Care Medicine. 2003;29:2144–2148. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-2035-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uyarel H, Ergelen M, Akkaya E, Ahyan E, Demirci D, Gul M, et al. Impact of day versus night as intervention time on the outcomes of primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions. 2009;74:826–834. doi: 10.1002/ccd.22154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West SH, Ahern M, Brynes M, Kwanten L. New graduate nurses adaptation to shift work: can we help? Collegian. 2007;14(1):23–30. doi: 10.1016/s1322-7696(08)60544-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Working Time Society [4 October];Scientific committee on shiftwork and working time of the international commission on occupational health. 2011 from http://www.workingtime.org.

- Wunsch H, Mapstone J, Brady T, Hanks R, Rowan K. Hospital mortality associated with day and time of admission to intensive care units. Intensive Care Medicine. 2004;30:895–901. doi: 10.1007/s00134-004-2170-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.