Abstract

A biomarker is a biological characteristic that is objectively measured and evaluated as an indicator of normal biological or pathologic processes or of pharmacologic responses to a therapeutic intervention. We review the current status on target protein biomarkers (e.g. total/oligomeric α-synuclein and DJ-1) in cerebrospinal fluid, as well as on unbiased processes that can be used to discover novel biomarkers. We also give details about strategies towards potential populations/models and technologies, including the need for standardized sampling techniques, to pursue the identification of new biochemical markers in the pre-motor stage of Parkinson disease in the future.

Keywords: Biomarkers, genomics, metabolomics, Parkinson disease, pre-motor, proteomics

1) Parkinson disease, pre-clinical diagnosis and biochemical biomarkers

The precise mechanisms underlying Parkinson Disease (PD) remain unclear and therefore require a better mechanistic understanding to ultimately identify marker candidates that are closely associated with the specific disease process (proximal markers). More than 50% of dopaminergic (DAergic) neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc) are degenerated when motor symptoms of parkinsonism is apparent, which, while enabling the clinical diagnosis of PD according to current clinical criteria1, makes it exceedingly challenging for any existing and/or future protective/regenerative therapies. It has been noted recently that many non-motor symptoms precede the motor symptoms of parkinsonism2 and should therefore be considered earlier during the disease course of PD. Biomarkers detecting PD in this “pre-motor phase” are urgently needed for neuroprotective therapies. The most mature biomarkers currently used to support the diagnosis of PD are derived from functional neuroimaging that assesses the integrity of the nigrostriatal system with ligands specific for dopamine (DA) metabolism or transport. However, because functional neuroimaging is expensive and not widely available, it is not suitable for routine clinical use. Also, it remains to be determined whether neuroimaging can reliably assess PD progression or treatment effects. Furthermore, at it stands now, these techniques are not suitable to differentiate between PD and other disorders with parkinsonism, such as multiple system atrophy (MSA), progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) and others. Finally, current neuroimaging techniques only reflect changes in the integrity of DAergic terminals but are not indicative of the underlying processes leading to progressive neuronal loss. Consequently, additional markers, particularly the biochemical markers reflecting PD pathogenesis at early stages of the disease, are needed to enable specific PD diagnosis, to follow PD progression, and to assess possible effects of interventions. It should be stressed, however, in the discovery of biochemical biomarkers, as of today, functional neuroimaging is the “gold-standard” used to define patients/subjects unequivocally at pre-motor stages.

Another major issue that needs to be emphasized is the heterogeneity of PD. Currently, the only mentioned clinical biomarker in the official criteria is the response to DAergic treatment, but many other PD clinical phenotypes to be discussed later are not treatable by DA medicines. Additionally, a peripheral component of PD is increasingly appreciated recently3,4; therefore the simultaneous measurement of several biomarkers for PD by so-called multiplexing is highly desired, and consequently heavily emphasized in the review.

2) Strategies to identify pre-motor PD biomarkers

It is impractical to screen general population for pre-motor biomarkers. In our opinion, there are a few potential ways of facilitating biomarker discovery in pre-motor stages.

First, clinical testing of those with recognized risks for developing PD

It is known that some non-motor features precede the onset of motor symptoms of PD for years. While these pre-motor signs are non-specific, with limited sensitivity/specificity for their clinical utility2, it is anticipated that objective pre-motor biomarkers can be identified in enriched populations based on the known non-motor features with high conversion rates for PD. Such studies could enclose participants with olfactory deficits, constipation, rapid eye movement (REM) sleep behavior disorder (RBD), and depression.

Second, following asymptomatic subjects with genetic mutations that give rise to familial PD

At least in theory, pre-motor PD markers can be searched for in familial PD (fPD) patients owing to genetic mutations, e.g. α-synuclein, DJ-1, pink1 and LRRK2. LRRK2 subjects are one of the ideal populations for pre-motor PD marker discovery because: 1) they avoid ambiguity of the markers discovered in animal models; 2) LRRK2 mutations produce parkinsonism closely resembling idiopathic or sporadic PD (sPD); and 3) unlike other PD genes, LRRK2 mutations are relatively common (1–2%) in typical late-onset sPD, thus providing adequate numbers of patients (and pre-motor relatives) for study of biomarkers. Nonetheless, there are also downsides to this approach in initial biomarker discovery. For instance, it is impossible to obtain the SNpc or striatum from these patients at early stages to study tissue specific markers, greatly decreasing the possibility of identifying tissue specific early stage biomarkers by “-omics” technologies (see below for more discussion).

Third, using animal models

Identifying markers in animal models initially, whether toxicant or genetic-based, and then testing these markers in human PD could be another effective way of discovering pre-motor biomarkers. One of the more effective animal models is nonhuman primates treated with N-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP). This model is not only the most investigated PD model available to date but also allows for identification of tissue/disease-specific markers related to nigrostriatal degeneration. The obvious caveat associated with the MPTP model, including the chronic progressive one used by several groups5 or any other animal models, such as the rotenone model and others (reviewed by Dehay et al recently6), centers around whether or not it faithfully replicates human PD.

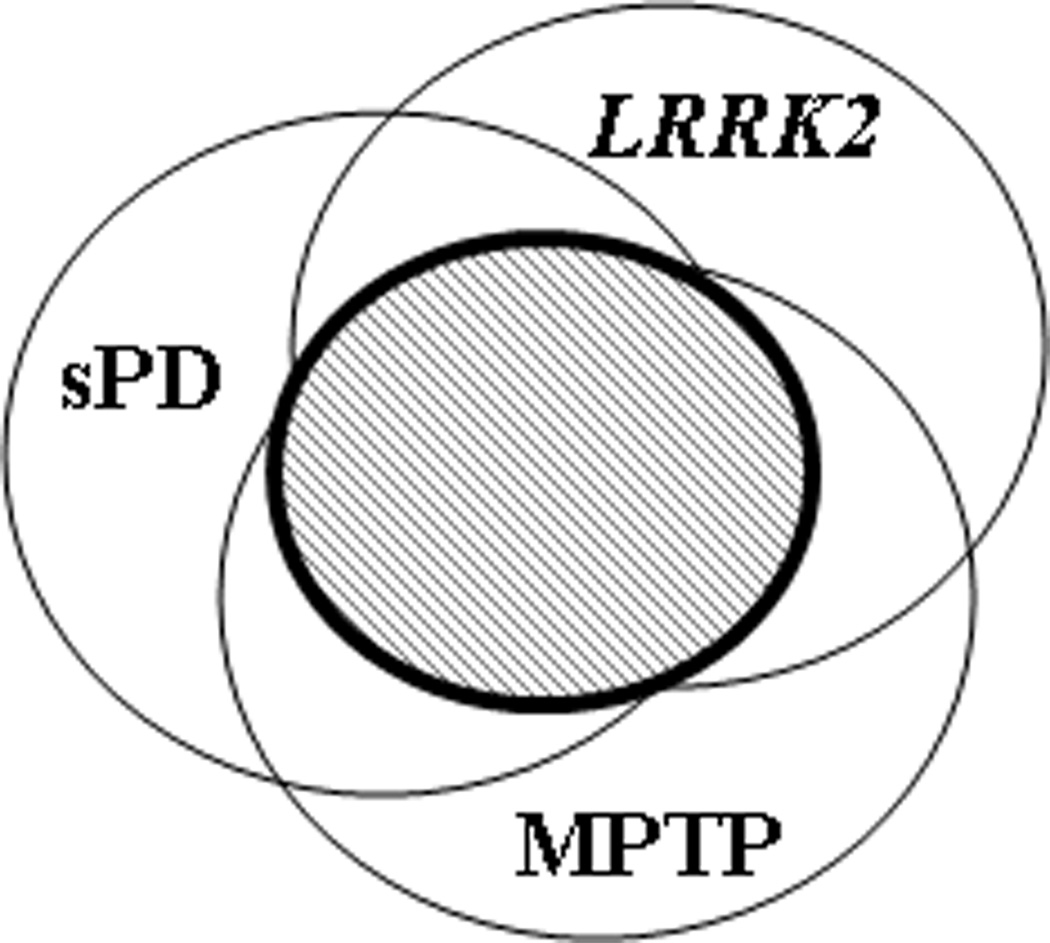

Thus, practically, one integrated approach could be using all three models in parallel to minimize the limitations associated with each model discussed above. Also, because advanced proteomics allows multiplex quantitative analysis, it is possible to compare the protein markers in monkeys and LRRK2-PD patients along with sPD cases, thereby enhancing the ability to identify the markers relevant to sPD. These markers can also be tested in those with non-motor symptoms to further enrich the populations at risk before expensive imaging methods are brought in to confirm the diagnosis of pre-motor stages. The hypothesis of this design is that, despite the fact that each model likely has its own unique aspects (and limitations), nigrostriatal neurodegeneration and associated cellular responses are common features to all of these models (shaded area in Fig 1), meaning that there will be a subset of markers common to all models.

Figure 1.

3) Biochemical biomarkers

Since brain-derived proteins rarely appear in peripheral biological fluids, such as blood and urine, optimal laboratory markers for neurodegenerative disease processes may not always be easily accessible. On the other hand, the collection of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is minimally invasive and very well-tolerated7, especially in older adults with a neurodegenerative illness. Furthermore, wider usage of new instruments, such as an ‘atraumatic’ needle for CSF collection, has decreased the incidence of side effects, such as a transient, positional headache that was often caused by a needle-induced tear in the arachnoid lining around the central nervous system (CNS)8. Additional evidence to support human CSF as an ideal source for identifying biomarkers for neurodegenerative diseases, including PD, is comprised of: 1) CSF is most proximal to the site of pathology; 2) CSF reflects the metabolic state of the brain under varying conditions and CNS diseases affect protein concentrations and patterns in CSF considerably; and 3) while 80% of the CSF proteins derive from the blood, 20% of the CSF proteome are synthesized within and released by resident cells of the CNS by means of active secretion, normal attrition, cell injury, or neural death9,10. Indeed, CSF obtained from PD patients modifies survival of DA neurons in a mesencephalic culture differently from those of controls11,12. In addition, analysis of human CSF with silver-stained twodimensional gel electrophoresis (2-D gel) has demonstrated that expression of some proteins may be linked to PD specifically13. Another important consideration is that, as discussed earlier, CSF is readily available, which makes longitudinal molecular analyses of changes in CSF during the course of neurological diseases possible. In fact, many groups are actively investigating biomarkers in CSF, and many candidate markers have been revealed. In the next few sections, we will summarize major results obtained in symptomatic PD patients as well as discuss the potential ways of going forward with premotor biomarker discovery.

3a) Targeted markers, α-synuclein and DJ-1, two proteins intimately associated with PD pathogenesis

Total and oligomeric α-synuclein

Predominantly expressed in the synaptic neuronal terminals, 140 amino-acid-long α-synuclein has been found to be the major constituent of the intracellular aggregates in Lewy bodies, the pathological hallmark of PD and dementia with Lewy-bodies (DLB), and in the glial cytoplasmic inclusions of MSA14,15.

Intracellular α-synuclein has been shown to be released into the extracellular space16, thereby promoting neuron-to-neuron transmission17. Full-length α-synuclein has been detected in biological fluids, including plasma, conditioned cell media and most recently saliva16,18. The quantification of extracellular α-synuclein has been proposed as a potential biomarker for synuclein-related diseases19-21. Discrepant findings by several investigators using several different platforms and operating procedures remain challenging, but the majority of investigators show a reduction of CSF total α-synuclein in the synuclein-related disorders, including PD, DLB and MSA - a consensus is emerging. In addition, commercially available assays are on their way, and quantification methods of the total α-synuclein or mono- vs oligomeric forms are also being developed.

The mechanism of the decreased CSF α-synuclein in Lewy body diseases, nonetheless, remains unclear to date and could result from various scenarios, such as the reduction of the α-synuclein release into the extracellular space due to intracellular aggregation; an alteration in SNCA gene transcription22, mRNA splicing23, or protein processing24; a higher CSF flow with lower permeation of plasma α-synuclein into CSF; an enhanced clearance rate of α-synuclein from CSF25; or yet unidentified factors or any combination of mechanisms19. While only one investigator so far showed a direct (negative) correlation with CSF α-synuclein levels and severity stages of PD in a cross sectional study comprising of 33 PD patients26, very litter is known about 1) its impact in the early (drug-naïve or even pre-motor) phase of synuclein-related disorders, 2) its potential value as progression marker shown in longitudinal cohorts, or 3) its significance regarding correlation with different clinical phenotypes in PD. Last, but not least, possible medication effect through DAergic therapy needs to be ruled out and possible relevant post-translationally modified (PTM) α-synuclein species need to be investigated19.

As mentioned earlier, assays to determine total or mono- vs oligomeric forms of α-synuclein have been established recently based on the same monoclonal antibody for capture and detection27. It appears that CSF values of oligomeric α-synuclein make up to 10% of the total α-synuclein content. Additional investigations show an increase of CSF oligomeric α-synuclein in PD compared to patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD), PSP and controls27,28. Together with the reduced CSF total α-synuclein, the ratio of oligomeric/total α-synuclein reveal a sensitivity of 89.3% and specificity of 90.6% for the diagnosis of PD in one study28.

DJ-1

DJ-1, a multifunctional protein involved in many cellular processes, including the response to oxidative stress, has been linked to PD in those with autosomal recessive gene mutation of the encoding region (familial PARK7)29 as well as in sporadic forms30,31. DJ-1 is present in CSF and showed elevated levels in PD, especially in the early stages (Hoehn and Yahr stages I-II) compared to advanced stages (Hoehn and Yahr stages IIIIV) and healthy controls31. Recently, however, decreased levels of DJ-1 were found in a large cohort of CSF samples of PD patients compared to healthy controls and AD patients32.

Since elevated levels of oxidized DJ-1 have been found in the brains of PD and AD patients30, specific antibodies recognizing C106-oxidized DJ-1 have been developed and await validation in biological fluids.

However, as discussed earlier, one of the major limitations of these ongoing investigations relates to the fact that PD patients, even at a clinically “early stage”, have already lost >50% of their nigral DAergic neurons at the time of diagnosis and all investigated cohorts so far were more advanced33. As a result, it is unclear whether these markers can be used for preclinical or pre-motor diagnosis of PD or monitoring of PD progression at early stages. Overcoming this limitation requires performing biomarker discovery in subjects at the asymptomatic stage, which is impractical unless one can first identify individuals at high-risk for developing PD as discussed above.

The other major challenge to the field is variation and sometimes even contradictory results of different investigators. Further investigations of the specificity of the antibodies and the total and oligomeric α-synuclein enzyme-linked immunoabsorbent assay (ELISA) techniques are needed. Independent studies of CSF α-synuclein are also necessary in optimally processed pre-motor cohorts of CSF as well as in other biological fluids. Finally, future investigations with larger and longitudinally characterized cohorts are needed to clarify a potential correlation and the possible use as progression markers or markers of pre-motor stages.

It should also be mentioned that, in addition to α-synuclein and DJ-1, other targeted biomarkers have been linked to an elevated or decreased risk of developing PD. Of particular note is the observation that the neurodegeneration in PD is lower in the subjects with high urate levels, which is an antioxidant, and in fact urate has been proposed as a neuroprotectant (please see a review by Cipriani et al34 for details). Other key proteins, e.g. parkin, and ubiquitin involved in PD pathogenesis could also be investigated as potential PD markers.

3b) Unbiased markers by "-omics" techniques

In addition to targeted approaches, discovering novel biomarkers unique to PD, symptomatic or pre-motor, can be greatly facilitated by “-omics” techniques, e.g. transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics, which have been developed in the last decade. Each technique has been applied to human samples (brain tissue, CSF, blood, plasma, urine) and reported a set of analytes with potential to differentiate PD from controls. In the next section, we will discuss a few markers revealed by each platform, along with potential caveats and shortcomings. Theoretically, these cutting-edge technologies can be applied to models/enriched populations (Fig. 1) for discovering pre-clinical markers.

Transcriptomics

The use of brain tissue in microarray analysis has provided invaluable insights to PD pathogenesis, including regional specificity, i.e. DA neurons in the SNpc are more sensitive (than those in the ventral tegmental area or VTA) to neurodegeneration35,36. However, the use of peripheral biological tissue sources, such as blood, where mRNAs can also be isolated readily, allows for a minimally invasive means of sampling a population and provides the researcher the ability to perform a longitudinal assessment of particular markers of interest in order to give an indication of pathways that may be altered as the disease progresses37. In this regard, by comparing blood taken from control and early stage PD patients, Scherzer and colleagues38,39 have identified ST13, a gene that was highly under-expressed in PD samples compared with control samples. ST13 is a cofactor for heat shock protein-70 (Hsp70), a protein that plays critical roles in the misfolding40 of modulating protein, e.g. α-synuclein. Unfortunately, a follow-up investigation by another group did not replicate this observation41.

Several important caveats that deserve consideration when undertaking a transcriptomic-based evaluation of mRNA expression differences between disease and normal states include: 1) not all alternations in mRNAs translate into changed protein or metabolite levels; 2) it remains controversial as to whether gene alterations in peripheral samples, i.e. WBCs obtained from blood, represent what is happening in the CNS. For the latter point, it should be stressed that PD is not just a disease with CNS pathology only (also see discussion on pre-motor symptoms above).

Proteomics

Like transcriptomics, proteomics generates enormous amounts of data, both identification and quantification of proteins, when comparing one disease state to another. On the other hand, in contrast to transcriptomics, in which all genes analyzed can be quantified simultaneously, identification of proteins by current proteomic technologies are heavily dependent upon abundance of proteins and pre-processing of samples (see a previous review42 for more details on this topic).

A few attempts have been made to reveal novel markers in CSF for symptomatic PD43-45; however, independent investigations are needed to validate these candidate markers, e.g. chromogranin B and apolipoprotein H44, as reproducible and clinically useful. Another major issue is that among >3,000 proteins identified in human CSF, those related to the CNS, structurally or functionally, are in minority46. The proteins specific to PD pathogenesis are even few in numbers.

In our opinion, the slow progress to identify unique CSF biomarkers in PD resulted from two major difficulties. First, the underlying pathogenic events are too complex to be accurately reflected in a single molecule. Second, PD pathology, though it becomes more diffuse in advanced stages of disease, is still relatively localized and the tissue/disease specific markers may be so dilute in CSF, a generalized pool of brain metabolic output, that they are very difficult to find unless being looked for specifically. To mitigate this limitation, tissue markers in pathologically involved brain regions that correlate with PD and PD progression need to be identified first, which is why we believe an animal model could be helpful (Fig 1). It is apparent that not all proteins identified in tissues will be present in CSF. In addition, as PD pathogenesis is largely unknown, the brain regions examined may not contain all of the protein markers in CSF that are diagnostic for PD or that play significant roles in PD progression. Hence, an ideal approach to discover PD biomarkers is an integrated one that involves both looking for brain region-specific markers and nonbiased profiling of optimally processed CSF proteins in well-characterized PD patients as well as asymptomatic subjects as discussed above.

Metabolomics

Until recently, the most promising metabolic marker for PD was the demonstration of an inverse correlation (see earlier discussion on this topic as well) between the concentration of urate, an endogenous antioxidant47, and clinical progression of PD, with reduced urate levels suggesting an increase in DAergic neurodegeneration and advanced PD symptomology34 48-51.

With introduction of metabolomics to PD research, several groups have explored the disruption of metabolic pathways in PD by analyzing human blood for metabolic signatures. The first study by Bogdanov et al.52 revealed a few alterations in metabolites associated with the oxidative stress pathway, including decreased uric acid, as well as increased glutathione and 8-OHdG. A more recent study by the same group elaborated upon their previous findings and used metabolomics to evaluate the metabolic profiles of patients with sPD, PD associated with the G2019S LRRK2 mutation, asymptomatic LRRK2 G2019S carriers, and normal controls53. Again, they were able to distinguish sPD cases from control, based on levels of metabolic signatures. Even more interesting, they reported a clear delineation between sPD and the LRRK2 PD group. Furthermore, a partial separation of LRRK2 PD patients and asymptomatic relatives who are carrying the LRRK2 mutation was also seen, although a substantial overlap between the two groups was present. This observation is consistent with our hypothesis that a subset of markers identified in LRRK2 patients can be applied to sPD patients.

One obvious issue (that is not necessarily unique to metabolomics) is: generally speaking, there is a lack of good reproducibility among different “-omics” investigations. While some variability is biological, e.g. the overall heterogeneity of the human population, a significant contribution to the inconsistent results relates to variables involved in experimentation with different technologies and incompleteness of current database for proteomics and metabolomics. Some of these issues can be resolved when less focus is put on the agreement of specific products and instead the entirety of the pathway within which particular genes/proteins/metabolites reside is considered. Indeed, when considering transcriptomics and proteomics, similar pathways have been shown to change between control and PD subjects, including synaptic transmission, mitochondrial function, protein degradation, and oxidative stress. Interestingly, when this approach is applied it appears that alteration to the oxidative stress pathway is a common feature discovered in transcriptomic, proteomic, as well as metabolomic studies of PD. Moreover, while the transcriptomic and proteomic studies discovered this alteration in human midbrain tissue, metabolomics uncovered this pathway in human serum. Given the agreement of this finding through three independent means in addition to different body tissues, these data provide a strong argument for the role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of PD. It should be emphasized that several altered proteins, e.g. mortalin, revealed by proteomics in PD patients54,55 are clearly related to mitochondrial function, and therefore, are probably worth further investigation by targeted investigation.

4) Concluding remarks and future directions

Advances, whether targeted testing or unbiased profiling, have been made in PD biomarker discovery over the last few years. However, many challenges lie ahead. First, there is the lack of widely used standardized operating procedures (SOP) for sample processing56, making it very difficult, if not impossible, to compare the results obtained by different groups. Moving forward, it is essential to process the samples as quickly as possible for any protein or metabolite studies of CSF (or any other biological fluids). It is clearly important to compare the results among different studies when the same sample protocol is followed. It has also been shown that the procedure length in CSF collection and the type of storage tube used will influence protein values, especially when analyzing lipophilic proteins (like β-amyloid and α-synuclein). This discovery was first made in CSF β-amyloid research57. Processing time, temperature, storage conditions and pH shifts can alter outcome, chiefly through the process of proteolysis. Standardization of the assays is essential before meaningfully tackling pre-motor markers by multiple groups.

It is also important to realize that PD (AD or any other major neurodegenerative disorders for that matter) is not a single disease; there are many sub-types of diseases in PD syndrome. In other words, it is expected that subgroups of PD patients could express different markers, i.e. a panel of markers will be needed for PD diagnosis/progression. This issue becomes more important in dealing with pre-motor markers - identifying several markers with a small ‘signal’ on their own in the early stage of the disease could provide a substantial signal when used in combination. This approach has been used extensively in cancer research. For instance, in a proteomic study, Petricoine et al. found that combining only 5 of over 1,200 protein candidates achieved a sensitivity of 100% with specificity of 95%58. Similarly, Blennow and associates have used tau, phosphorylated tau, and β-amyloid simultaneously in human CSF to differentiate AD from controls as well as other types of dementia59. We have also recently used a combination of eight markers to classify PD with high sensitivity and specificity60.

Finally, while most current clinical assays for PD (or AD) biomarkers are purely based on antibodies, other new platforms, e.g. multiplexed immuno-PCR and mass spectrometry, quickly become available to major medical centers and hospitals. Mass spectrometry techniques, e.g. multiple reaction monitoring (MRM)61, deserve special attention since they do not need specific antibodies.

In summary, by applying advanced technology and standardization of the protocols and assays, we believe pre-motor biochemical biomarkers can be discovered in populations at risk for developing PD. Using appropriate animal models can also facilitate this incredibly important process.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms. Victoria Herradura for her effort in preparation of the manuscript. Dr. Mollenhauer's effort is supported by the Michael J. Fox Foundation (MJFF) for Parkinson’s Research, the American Parkinson’s Disease Association and the Stifterverband für die Deutsche Wissenschaft (Dr. Werner Jackstädt-Stipendium); She additionally received grants from TEVA-Pharma, Desitin, Boehringer Ingelheim and GE Healthcare and honoraria for consultancy from Bayer Schering Pharma AG and for presentations from GlaxoSmithKline and Orion Pharma as well as travel/meeting expenses from Boehringer-Ingelheim and Novartis. Dr. Mollenhauer also serves as consultant for MJFF (PPMI). Dr. Zhang's effort is supported by grants from MJFF and NIH (AG033398, ES004696-5897-Project 3, ES007033-6364-Facility Core, ES016873, ES019277, NS057567, and NS062684-6221-Facility Core).

Footnotes

Author Contributorship Statement: Both authors contributed to the writing of this review article.

Contributor Information

Brit Mollenhauer, Paracelsus-Elena-Klinik and Georg August University, Goettingen, Kassel, Germany.

Jing Zhang, Department of Pathology, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98104.

References

- 1.Hughes AJ, Daniel SE, Kilford L, Lees AJ. Accuracy of clinical diagnosis of idiopathic Parkinson's disease: a clinico-pathological study of 100 cases. 1992;55:181–184. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.55.3.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chaudhuri KR, Naidu Y. Early Parkinson's disease and non-motor issues. J Neurol. 2008;255(Suppl 5):33–38. doi: 10.1007/s00415-008-5006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Del Tredici K, Hawkes CH, Ghebremedhin E, Braak H. Lewy pathology in the submandibular gland of individuals with incidental Lewy body disease and sporadic Parkinson's disease. Acta Neuropathol. 119:703–713. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0665-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valappil RA, et al. Exploring the electrocardiogram as a potential tool to screen for premotor Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 25:2296–2303. doi: 10.1002/mds.23348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Masilamoni GJ, et al. Metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 antagonist protects dopaminergic and noradrenergic neurons from degeneration in MPTP-treated monkeys. Brain. 2011;134:2057–2073. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dehay B, Bezard E. New animal models of Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 26:1198–1205. doi: 10.1002/mds.23546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andreasen N, et al. Evaluation of CSF-tau and CSF-Abeta42 as diagnostic markers for Alzheimer disease in clinical practice. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:373–379. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.3.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peskind ER, et al. Safety and acceptability of the research lumbar puncture. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2005;19:220–225. doi: 10.1097/01.wad.0000194014.43575.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reiber H. Dynamics of brain-derived proteins in cerebrospinal fluid. Clin Chim Acta. 2001;310:173–186. doi: 10.1016/s0009-8981(01)00573-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reiber H. Flow rate of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)--a concept common to normal blood-CSF barrier function and to dysfunction in neurological diseases. J Neurol Sci. 1994;122:189–203. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(94)90298-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Le WD, Rowe DB, Jankovic J, Xie W, Appel SH. Effects of cerebrospinal fluid from patients with Parkinson disease on dopaminergic cells. Arch Neurol. 1999;56:194–200. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.2.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu SJ, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid from patients with Parkinson's disease alters the survival of dopamine neurons in mesencephalic culture. Experimental neurology. 1994;126:15–24. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1994.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harrington MG, Merril CR. Cerebrospinal fluid protein analysis in diseases of the nervous system. J Chromatogr. 1988;429:345–358. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)83877-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spillantini MG, et al. Alpha-synuclein in Lewy bodies. Nature. 1997;388:839–840. doi: 10.1038/42166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gai WP, Power JH, Blumbergs PC, Blessing WW. Multiple-system atrophy: a new alpha-synuclein disease? Lancet. 1998;352:547–548. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)79256-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.El-Agnaf OM, et al. Alpha-synuclein implicated in Parkinson's disease is present in extracellular biological fluids, including human plasma. Faseb J. 2003;17:1945–1947. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0098fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Desplats P, et al. Inclusion formation and neuronal cell death through neuron-to-neuron transmission of alpha-synuclein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:13010–13015. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903691106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Devic I, et al. Salivary alpha-synuclein and DJ-1: potential biomarkers for Parkinson's disease. Brain. 2011;134:e178. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mollenhauer B, El-Agnaf OM, Marcus K, Trenkwalder C, Schlossmacher MG. Quantification of alpha-synuclein in cerebrospinal fluid as a biomarker candidate: review of the literature and considerations for future studies. Biomark Med. 2010;4:683–699. doi: 10.2217/bmm.10.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shi M, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers for Parkinson disease diagnosis and progression. Ann Neurol. 2011;69:570–580. doi: 10.1002/ana.22311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aerts MB, Esselink RA, Abdo WF, Bloem BR, Verbeek MM. CSF alpha-synuclein does not differentiate between parkinsonian disorders. Neurobiol Aging. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cantuti-Castelvetri I, et al. Alpha-synuclein and chaperones in dementia with Lewy bodies. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2005;64:1058–1066. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000190063.90440.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beyer K, et al. Low alpha-synuclein 126 mRNA levels in dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer disease. Neuroreport. 2006;17:1327–1330. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000224773.66904.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anderson JP, et al. Phosphorylation of Ser 129 is the dominant pathological modification of alpha -synuclein in familial and sporadic Lewy body disease. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:29739–29752. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600933200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chodobski A, Szmydynger-Chodobska J. Choroid plexus: target for polypeptides and site of their synthesis. Microsc Res Tech. 2001;52:65–82. doi: 10.1002/1097-0029(20010101)52:1<65::AID-JEMT9>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tokuda T, et al. Decreased alpha-synuclein in cerebrospinal fluid of aged individuals and subjects with Parkinson's disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;349:162–166. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.El-Agnaf OM, et al. Detection of oligomeric forms of alpha-synuclein protein in human plasma as a potential biomarker for Parkinson's disease. Faseb J. 2006;20:419–425. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1449com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tokuda T, et al. Detection of elevated levels of {alpha}-synuclein oligomers in CSF from patients with Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2010;75:1766–1772. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181fd613b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bonifati V, Oostra BA, Heutink P. Linking DJ-1 to neurodegeneration offers novel insights for understanding the pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease. J Mol Med. 2004;82:163–174. doi: 10.1007/s00109-003-0512-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Choi J, et al. Oxidative damage of DJ-1 is linked to sporadic Parkinson and Alzheimer diseases. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:10816–10824. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509079200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Waragai M, et al. Increased level of DJ-1 in the cerebrospinal fluids of sporadic Parkinson's disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;345:967–972. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hong Z, et al. DJ-1 and alpha-synuclein in human cerebrospinal fluid as biomarkers of Parkinson's disease. Brain. 2010;133:713–726. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lowe JS, Leigh N. Disorders of movement and system degenerations. In: Graham DI, Lantos PL, editors. Greenfield's Neuropathology. Vol. II. London: Arnold; 2002. pp. 325–430. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cipriani S, Chen X, Schwarzschild MA. Urate: a novel biomarker of Parkinson's disease risk, diagnosis and prognosis. Biomark Med. 4:701–712. doi: 10.2217/bmm.10.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lu L, et al. Gene expression profiles derived from single cells in human postmortem brain. Brain Res Brain Res Protoc. 2004;13:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresprot.2003.12.003. Write to the Help Desk NCBI | NLM | NIH Department of Health & Human Services Privacy Statement | Freedom of Information Act | Disclaimer

- 36. Grimm J, Mueller A, Hefti F, Rosenthal A. Molecular basis for catecholaminergic neuron diversity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:13891–13896. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405340101. Epub 12004 Sep 13807. Write to the Help Desk NCBI | NLM | NIH Department of Health & Human Services Privacy Statement | Freedom of Information Act | Disclaimer

- 37.Zhang J, Goodlett DR, Montine TJ. Proteomic biomarker discovery in cerebrospinal fluid for neurodegenerative diseases. J Alzheimers Dis. 2005;8:377–386. doi: 10.3233/jad-2005-8407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scherzer CR, et al. Molecular markers of early Parkinson's disease based on gene expression in blood. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:955–960. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610204104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scherzer CR, et al. GATA transcription factors directly regulate the Parkinson's disease-linked gene alpha-synuclein. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:10907–10912. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802437105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Klucken J, Shin Y, Masliah E, Hyman BT, McLean PJ. Hsp70 Reduces alpha-Synuclein Aggregation and Toxicity. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004;279:25497–25502. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400255200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shadrina MI, et al. Expression analysis of suppression of tumorigenicity 13 gene in patients with Parkinson's disease. Neuroscience letters. 473:257–259. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.02.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang J. Proteomics of human cerebrospinal fluid - the good, the bad, the ugly. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2007;1:805–819. doi: 10.1002/prca.200700081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Davidsson P, Sjogren M. The use of proteomics in biomarker discovery in neurodegenerative diseases. Disease markers. 2005;21:81–92. doi: 10.1155/2005/848676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Abdi F, et al. Detection of biomarkers with a multiplex quantitative proteomic platform in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with neurodegenerative disorders. J Alzheimers Dis. 2006;9:293–348. doi: 10.3233/jad-2006-9309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pan S, et al. Application of Targeted Quantitative Proteomics Analysis in Human Cerebrospinal Fluid Using a Liquid Chromatography Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Time-of-Flight Tandem Mass Spectrometer (LC MALDI TOF/TOF) Platform. J Proteome Res. 2008;7:720–730. doi: 10.1021/pr700630x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pan S, et al. A combined dataset of human cerebrospinal fluid proteins identified by multi-dimensional chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry. Proteomics. 2007;7:469–473. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200600756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ames BN, Cathcart R, Schwiers E, Hochstein P. Uric acid provides an antioxidant defense in humans against oxidant- and radical-caused aging and cancer: a hypothesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1981;78:6858–6862. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.11.6858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ascherio A, et al. Urate as a predictor of the rate of clinical decline in Parkinson disease. Archives of neurology. 2009;66:1460–1468. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schwarzschild MA, et al. Serum urate as a predictor of clinical and radiographic progression in Parkinson disease. Archives of neurology. 2008;65:716–723. doi: 10.1001/archneur.2008.65.6.nct70003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schlesinger I, Schlesinger N. Uric acid in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2008;23:1653–1657. doi: 10.1002/mds.22139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weisskopf MG, O'Reilly E, Chen H, Schwarzschild MA, Ascherio A. Plasma urate and risk of Parkinson's disease. American journal of epidemiology. 2007;166:561–567. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bogdanov M, et al. Metabolomic profiling to develop blood biomarkers for Parkinson's disease. Brain. 2008;131:389–396. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Johansen KK, et al. Metabolomic profiling in LRRK2-related Parkinson's disease. PloS one. 2009;4:e7551. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jin J, et al. Proteomic identification of a stress protein, mortalin/mthsp70/GRP75: relevance to Parkinson disease. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:1193–1204. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500382-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shi M, et al. Mortalin: A Protein Associated With Progression of Parkinson Disease? J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2008 doi: 10.1097/nen.0b013e318163354a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mattsson N, Blennow K, Zetterberg H. Inter-laboratory variation in cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers for Alzheimer's disease: united we stand, divided we fall. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2010;48:603–607. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2010.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bibl M, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid amyloid beta peptide patterns in Alzheimer's disease patients and nondemented controls depend on sample pretreatment: indication of carrier-mediated epitope masking of amyloid beta peptides. Electrophoresis. 2004;25:2912–2918. doi: 10.1002/elps.200305992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Petricoin EF, et al. Use of proteomic patterns in serum to identify ovarian cancer. Lancet. 2002;359:572–577. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07746-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Olsson A, et al. Simultaneous Measurement of {beta}-Amyloid(1-42), Total Tau, Phosphorylated Tau (Thr181) in Cerebrospinal Fluid by the xMAP Technology. Clin Chem. 2005;51:336–345. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2004.039347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang J, et al. CSF Multianalyte Profile Distinguishes Alzheimer and Parkinson Diseases. American journal of clinical pathology. 2008;129:526–529. doi: 10.1309/W01Y0B808EMEH12L. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Anderson L, Hunter CL. Quantitative mass spectrometric multiple reaction monitoring assays for major plasma proteins. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:573–588. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500331-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]