Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

To determine if state laws regulating nutrition content of foods and beverages sold outside of federal school meal programs (“competitive foods”) are associated with lower adolescent weight gain.

METHODS:

The Westlaw legal database identified state competitive food laws that were scored by using the Classification of Laws Associated with School Students criteria. States were classified as having strong, weak, or no competitive food laws in 2003 and 2006 based on law strength and comprehensiveness. Objective height and weight data were obtained from 6300 students in 40 states in fifth and eighth grade (2004 and 2007, respectively) within the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study–Kindergarten Class. General linear models estimated the association between baseline state laws (2003) and within-student changes in BMI, overweight status, and obesity status. Fixed-effect models estimated the association between law changes during follow-up (2003–2006) and within-student changes in BMI and weight status.

RESULTS:

Students exposed to strong laws at baseline gained, on average, 0.25 fewer BMI units (95% confidence interval: −0.54, 0.03) and were less likely to remain overweight or obese over time than students in states with no laws. Students also gained fewer BMI units if exposed to consistently strong laws throughout follow-up (β = −0.44, 95% confidence interval: −0.71, −0.18). Conversely, students exposed to weaker laws in 2006 than 2003 had similar BMI gain as those not exposed in either year.

CONCLUSIONS:

Laws that regulate competitive food nutrition content may reduce adolescent BMI change if they are comprehensive, contain strong language, and are enacted across grade levels.

KEY WORDS: competitive foods, state laws, BMI, adolescent

What’s Known on This Subject:

Policies that govern nutrition standards of foods and beverages sold outside of federal meal programs (“competitive foods”) have been associated with adolescent weight status in a small number of cross-sectional studies and pre-post analyses in individual states.

What This Study Adds:

This longitudinal analysis of 6300 students in 40 states provides evidence that state competitive food laws are associated with lower within-student BMI change if laws contain strong language with specific standards and are consistent across grade levels.

National medical organizations,1–3 policymakers,4,5 and the federal government6,7 have called for bold policy initiatives to reduce adolescent obesity in the United States. Nearly one-fifth of 12- to 19-year-olds in the United States were obese in 2009 to 2010 (18.4%),8 and the long-term effects of adolescent obesity on morbidity and premature mortality during adulthood are well documented.9 As the US population ages, the public health and economic burden of obesity is expected to grow.10–13

Numerous interventions have attempted to reduce adolescent obesity by educating adolescents to be active and consume a healthy diet, but education-based interventions have had little success.14,15 Experts argue that education will not suffice without changing the contemporary “obesogenic” environment in which adolescents have countless sources of high-caloric-density, low-nutrient-density foods and beverages.16–18 Schools have become a source of sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs), candy, and other foods and beverages of minimal nutritional value.19–21 Particularly at higher grade levels, school food environments include widespread availability of “competitive foods”22 (foods and beverages sold outside of meal programs) that have historically been exempt from federal nutrition standards.2

The Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010 requires, among several provisions, that competitive foods be subject to standards set by the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) in schools that participate in federal meal programs.23 Some experts questioned the potential impact of such policies by noting that students consume a relatively small proportion of their daily calories at school and can compensate for school changes by obtaining energy-dense foods elsewhere.24–27 Furthermore, school nutrition regulations are politically controversial, as illustrated by recent debates in Congress regarding proposed USDA school meal standards that are intended to align standards with current nutrition science. Dialogue on the topic has been limited by the lack of longitudinal evidence regarding the association between school nutrition policies and student weight status. Research has suggested that competitive food policies are associated with improvements in the school food environment, student dietary intake, or weight outcomes,28–34 but most studies were cross-sectional or limited to individual states. A recent study reported no association between competitive food sales and weight gain, but it was based on school administrator surveys rather than independent review of codified laws.35 Studies that analyzed weight outcomes also generally relied on self-reported height and weight, which can be misreported.36

To address these limitations, this longitudinal study was designed to estimate the association between independently coded state laws governing competitive food nutrition content and within-student change in BMI and weight status, based on objective height and weight data collected from adolescents in 40 states. We estimated the association between baseline state laws and student weight change, as well as the association between changes in state laws over time and student weight change.

Methods

Competitive Food Laws

State codified laws regarding the availability of high-caloric-density, low-nutrient-density foods and beverages in schools were obtained from the National Cancer Institute’s Classification of Laws Associated with School Students school nutrition scoring system.37,38 Statutory and administrative (regulatory) laws were compiled by using natural language and Boolean keyword searches of the full-text, table of contents, and indices for state laws available from Westlaw, a subscription-based legal research database. Our analyses were based on 6 different categories of laws: those governing nutrition content of competitive foods sold in (1) vending machines, (2) cafeterias (à la carte), and (3) other venues (eg, stores); and those governing nutrition content of competitive beverages in each of the 3 locations. Laws included regulations of specific nutrients (eg, fat content), specific beverage groups (eg, SSBs), and times of day when foods/beverages could be sold.

States were rated on a scale of 0 to 6 in each category of laws, independently and annually, beginning in 2003. Ratings reflected relative stringency, specificity, and strength of language of laws that were in place as of December 31 of that year. Laws governing different grade levels were rated separately. In any given year and grade level, most states applied the same laws across all venues rather than requiring restrictions only in specific venues. Because of the high within-state correlation, we used the average of the 6 ratings as a comprehensive measure of state competitive food laws.

For the purpose of this study, states were categorized as having “strong” competitive food laws if their average rating was >2.0. The cut point was chosen because ratings >2 represent laws with specific, required standards, as opposed to laws that contained weak language (eg, “recommended” standards) or no specific guidelines (eg, references to “healthy” foods). Additional details on the law ratings criteria can be found elsewhere.38 States with an average rating of 1 to 2 were categorized as having “weak” competitive food laws. We explored using a higher cut point to define strong laws (eg, 5.0), but there were not enough states with high ratings to support such an analysis.

Participants

Student data were obtained from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study–Kindergarten Class (ECLS-K).39,40 ECLS-K is a cohort that began as a nationally representative sample of kindergarten students in 1998 and was followed through 7 rounds of data collection. Analyses in this study were based on data from public school students measured in round 6 (fifth grade, Spring 2004) and round 7 (eighth grade, Spring 2007). Among the 8870 public school students who provided BMI data in fifth grade, 2570 were excluded from analyses because they enrolled in a private school (n = 130), moved states (n = 150), were missing data on eighth-grade school type (n = 220) or BMI (n = 390), or were lost to follow-up (n = 1680), leaving a final sample of 6300 students. Those excluded were less likely to be non-Hispanic white (P < .001) and more likely to live in an urban area (P < .001) or be below the poverty line in fifth grade (P < .001). They did not differ from the study sample in terms of fifth grade BMI, obesity prevalence, or overweight prevalence. Forty states were represented in the study sample; individual states cannot be listed because of data license restrictions. States that were not represented did not differ from the sample with respect to state median income, poverty rate, adult education, or obesity prevalence, but tended to have weaker laws.

ECLS-K researchers measured student weight and height in each survey round by using a digital scale and Shorr board, respectively. BMI was calculated (kg/m2) and students were categorized as overweight or obese if their BMI was greater than or equal to the age- and gender-specific 85th or 95th percentiles, respectively, of the 2000 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention growth charts.41

Statistical Analysis

The independent variables of interest were 2003 state law category and changes in state laws from 2003 to 2006. These years preceded the spring seasons when student data were collected. The dependent variables of interest were within-student changes in BMI (continuous), obesity status (binary), and overweight status (binary). Overweight status included students classified as obese. BMI was used in lieu of BMI percentile or z score because the variability of changes in BMI percentile and z score are associated with baseline values of these measures,42 which can bias SE estimates.

General linear models with an identity link were used to estimate differences across 2003 middle school law categories (strong, weak, none) in each dependent variable. Middle school laws were used because students were enrolled in middle school for most of the follow-up period. When modeling obesity, the sample was separated into 2 groups (students who were not obese in fifth grade and students who were obese in fifth grade) and eighth grade obesity status was modeled in each group to estimate incidence and maintenance of obesity, respectively. The same approach was used when modeling overweight status. Models adjusted for gender, age, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, non-Hispanic other), socioeconomic status (SES; measured by using an index that combined data on parental education, occupation, and income),39 school locale (city, suburb, township/rural), Census region (South versus other), physical activity, and 2003 state adult obesity prevalence.43 Eighth-grade physical activity was measured by asking students to report the number of days they engaged in at least 20 minutes of activity that made them sweat or breathe hard in the past week (fifth-grade activity was parent reported and therefore not used in longitudinal analyses because of inconsistent measurement across waves.) A robust SE was used to account for within-state clustering.

When analyzing 2003 to 2006 law changes, states were categorized by using 2 criteria. First, states were categorized based on whether their average rating for 2006 middle school laws was equal, higher, or lower compared with their average rating for 2003 elementary school laws (“no change,” “new laws,” or “weaker laws,” respectively). The respective grade levels were chosen because our objective was to analyze the change that students experienced as they progressed from fifth to eighth grade, which represents a transition from elementary to middle school for most students. Second, the new laws category was subdivided into 2 categories (strong or weak) and the no change category was subdivided into 3 categories (strong, weak, none). The weaker laws category was not subdivided because of the small sample size. An individual-level fixed-effect model was used to estimate differences between categories in within-student changes in BMI, overweight, or obesity, adjusted for SES and locale.

As a supplementary analysis, we repeated these models by using changes in within-school purchasing of sweets, salty snacks, and SSBs as dependent variables (continuous). Each behavior was measured by asking students to report the number of times they purchased the food/beverage group in school within the past week. Analyses were conducted with Stata, Version 11 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Table 1 illustrates the differences between law categories in race/ethnicity, SES, and Census region. States with no 2003 laws had a relatively low proportion of students who were non-Hispanic black (9.0%) or in the lowest SES quintile (15.7%). States with weak 2003 laws had a relatively high proportion of students who were Hispanic (28.0%) or in the lowest SES quintile (23.8%). Nearly 70% of students in states with strong 2003 laws lived in the South, whereas only 5.7% lived in the West. Conversely, students exposed to weaker laws in 2006 were entirely from the South, whereas 65.5% of students exposed to new strong laws in 2006 were from the West.

TABLE 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Study Sample, Overall and by State Law Category

| Overall | 2003–2006 Law Change | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2003 Law | No Change | New Laws | Weaker | |||||||

| None | Weak | Strong | None | Weak | Strong | Weak | Strong | |||

| No. of states | 40 | 27 | 7 | 6 | 15 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 4 |

| Student variables | ||||||||||

| n | 6300 | 3720 | 1620 | 960 | 2090 | 410 | 900 | 1040 | 1270 | 590 |

| Gender, % | ||||||||||

| Female | 49.8 | 49.3 | 51.3 | 49.0 | 48.2 | 49.0 | 51.8 | 49.9 | 51.6 | 48.7 |

| Race/ethnicity, % | ||||||||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 58.9 | 64.1 | 45.5 | 61.9 | 59.3 | 74.4 | 60.9 | 78.3 | 39.6 | 51.7 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 11.9 | 9.0 | 14.9 | 18.5 | 9.2 | 9.5 | 11.6 | 7.1 | 7.3 | 42.6 |

| Hispanic | 18.5 | 15.7 | 28.0 | 13.3 | 17.1 | 8.2 | 18.5 | 8.3 | 39.6 | 2.6 |

| Other, non-Hispanic | 10.7 | 11.2 | 11.8 | 6.4 | 14.4 | 8.0 | 8.9 | 6.4 | 13.5 | 3.1 |

| SES quintile, % | ||||||||||

| 1 | 18.1 | 15.7 | 23.8 | 17.8 | 18.0 | 10.2 | 12.4 | 12.0 | 25.2 | 28.0 |

| 2 | 20.2 | 20.5 | 18.6 | 21.2 | 22.3 | 15.5 | 17.2 | 19.2 | 20.0 | 22.3 |

| 3 | 19.6 | 20.5 | 17.4 | 19.5 | 21.0 | 17.5 | 20.2 | 20.4 | 17.3 | 18.2 |

| 4 | 21.3 | 22.7 | 18.5 | 20.8 | 22.0 | 23.3 | 24.7 | 23.3 | 17.8 | 16.3 |

| 5 | 20.9 | 20.6 | 21.7 | 20.7 | 16.7 | 33.5 | 25.5 | 25.1 | 19.7 | 15.3 |

| Locale, % | ||||||||||

| City | 31.6 | 30.3 | 37.3 | 26.7 | 30.9 | 33.0 | 35.7 | 24.3 | 44.2 | 12.4 |

| Suburban | 40.2 | 40.2 | 39.6 | 41.4 | 33.5 | 56.4 | 48.0 | 47.9 | 37.1 | 34.9 |

| Township/Rural | 28.2 | 29.5 | 23.1 | 30.2 | 35.6 | 10.6 | 16.3 | 27.9 | 18.6 | 52.7 |

| Region, % | ||||||||||

| Northeast | 18.9 | 15.7 | 22.1 | 25.7 | 3.5 | 45.1 | 27.7 | 43.9 | 17.9 | 0.0 |

| Midwest | 27.6 | 42.6 | 9.8 | 0.0 | 50.3 | 38.5 | 32.7 | 22.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| South | 32.9 | 27.2 | 24.9 | 68.6 | 34.9 | 16.3 | 33.4 | 16.7 | 16.6 | 100.0 |

| West | 20.6 | 14.5 | 43.3 | 5.7 | 11.2 | 0.0 | 6.2 | 16.9 | 65.5 | 0.0 |

| BMI, mean | ||||||||||

| 5th grade | 20.7 | 20.5 | 21.2 | 20.9 | 20.5 | 20.7 | 20.5 | 20.3 | 21.1 | 21.6 |

| 8th grade | 23.1 | 22.9 | 23.5 | 23.1 | 23.0 | 23.0 | 22.6 | 22.5 | 23.4 | 24.2 |

| Overweight, % | ||||||||||

| 5th grade | 40.1 | 36.9 | 46.0 | 42.1 | 36.6 | 43.3 | 38.7 | 37.2 | 44.9 | 46.7 |

| 8th grade | 37.4 | 35.2 | 42.7 | 36.8 | 35.8 | 39.5 | 33.9 | 33.5 | 41.7 | 44.5 |

| Obesity, % | ||||||||||

| 5th grade | 22.3 | 20.4 | 25.9 | 23.3 | 21.2 | 21.3 | 20.8 | 18.7 | 26.3 | 26.6 |

| 8th grade | 20.3 | 18.9 | 23.3 | 20.6 | 19.9 | 19.5 | 17.5 | 17.0 | 23.8 | 25.0 |

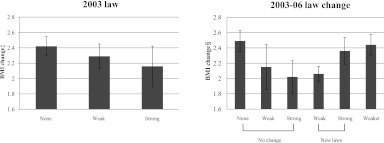

Figure 1 displays the adjusted mean within-student BMI change by state law categories. Students in states with weak 2003 laws (ie, laws that contained weak language or nonspecific standards) had, on average, a slightly smaller increase in BMI compared with students in states with no relevant laws (β = –0.13, 95% confidence interval [CI]: –0.34, 0.07). The difference in BMI change was nearly twice as large when comparing students in states with strong 2003 laws (ie, laws with specific, required standards) with those in states with no relevant laws (β = –0.25, 95% CI: –0.54, 0.03). Results of 2003 law analyses were similar when modeling overweight or obesity maintenance (Table 2). Students in states with strong laws were less likely to remain overweight (risk difference = –4.8, 95% CI: –9.4, –0.1) or obese (risk difference = –7.7, 95% CI: –16.0, 0.6) from fifth to eighth grade, but the same was not true in states with weak laws.

FIGURE 1.

Adjusted within-student BMI change, by 2003 state law* and 2003–2006 law change.† *State middle school law in 2003. †Difference between mean rating for state elementary school laws in 2003 and middle school laws in 2006. No change–none: Equal mean rating (0). No change–weak: Equal mean rating (1–2). No change–strong: Equal mean rating (>2). New laws–weak: Mean higher for 2006 middle school laws (1–2). New laws–strong: Mean higher for 2006 middle school laws (>2). Weaker: Mean lower for 2006 middle school laws. ‡Adjusted for race/ethnicity, gender, age, locale, SES, Census region, physical activity level, and 2003 state obesity prevalence. §Estimated from fixed-effect model, adjusted for SES and locale.

TABLE 2.

Maintenancesa and Incidenceb of Overweight or Obesity Status, by Strength of 2003 State Competitive Food Laws

| Weight Measure | 2003 Law | Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | 95% CI | RDc | 95% CI | P Value | ||

| Maintenance | ||||||

| Overweight | ||||||

| None | 80.1 | 78.1, 82.1 | — | — | — | |

| Weak | 79.0 | 77.4, 80.7 | −2.6 | −5.8, 0.5 | .10 | |

| Strong | 77.0 | 72.3, 81.8 | −4.8 | −9.4, -0.1 | .04 | |

| Obesity | ||||||

| None | 74.1 | 70.4, 77.8 | — | — | — | |

| Weak | 74.5 | 71.9, 77.0 | 0.5 | −3.3, 4.2 | .81 | |

| Strong | 70.5 | 62.9, 78.2 | −7.7 | −16.0, 0.6 | .07 | |

| Incidence | ||||||

| Overweight | ||||||

| None | 8.9 | 7.7, 10.1 | — | — | — | |

| Weak | 11.7 | 9.3, 14.2 | 2.4 | 0.8, 4.0 | .003 | |

| Strong | 7.5 | 5.8, 9.3 | −0.8 | −2.6, 0.9 | .35 | |

| Obesity | ||||||

| None | 4.7 | 4.1, 5.4 | — | — | — | |

| Weak | 5.4 | 4.6, 6.3 | 0.1 | −1.1, 1.3 | .84 | |

| Strong | 5.4 | 4.0, 6.8 | 0.5 | −1.3, 2.3 | .60 | |

—, referent category.

Risk of remaining overweight/obese between fifth and eighth grade.

Risk of developing overweight/obesity between fifth and eighth grade.

Absolute difference in risk of maintaining or developing overweight/obesity, adjusted for race/ethnicity, gender, age, locale, SES, region, and 2003 state obesity prevalence.

Results from analyses of 2003 to 2006 law changes (Table 3) generally echoed analyses of 2003 laws. Students who were exposed to consistent, specific, required competitive food laws from 2003 to 2006 gained 0.44 fewer BMI units than students who were not exposed to any relevant laws over time (95% CI: –0.71, –0.18). Students exposed to weaker laws in 2006 had approximately the same BMI change as those who were not exposed to any relevant laws throughout follow-up (β = –0.04, 95% CI: –0.24, 0.15). Surprisingly, students exposed to new laws in 2006 gained fewer BMI units if new laws were weak (β = –0.39, 95% CI: –0.56, –0.22) but not if new laws were strong (β = –0.10, 95% CI: –0.33, 0.12). Law change categories were associated with lower probability of being overweight, with differences ranging from –2.8% to –4.5%, but were not associated with probability of being obese.

TABLE 3.

Adjusted Differences Between 2003 and 2006 Law Change Categories in Within-Student Change in BMI or Weight Statusa

| Weight Measure | 2003–2006 Lawb | βc | 95% CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI | ||||

| No change–weak | −0.32 | −0.70, 0.05 | .09 | |

| No change–strong | −0.44 | −0.71, −0.18 | .002 | |

| New laws–weak | −0.39 | −0.56, −0.22 | .001 | |

| New laws–strong | −0.10 | −0.33, 0.12 | .36 | |

| Weaker laws | −0.04 | −0.24, 0.15 | .66 | |

| Overweight | ||||

| No change–weak | −4.0 | −9.8, 1.8 | .17 | |

| No change–strong | −3.6 | −7.5, 0.3 | .07 | |

| New laws–weak | −4.5 | −6.0, −3.0 | .001 | |

| New laws–strong | −2.8 | −5.5, −0.2 | .04 | |

| Weaker laws | −3.2 | −6.3, −0.1 | .04 | |

| Obesity | ||||

| No change–weak | −1.2 | −4.8, 2.5 | .52 | |

| No change–strong | −0.9 | −3.4, 1.6 | .46 | |

| New laws–weak | −0.8 | −2.7, 1.1 | .40 | |

| New laws–strong | 0.0 | −1.8, 2.0 | .94 | |

| Weaker laws | −0.4 | −5.1, 4.3 | .88 |

Referent: States with mean rating = 0 for elementary school laws in 2003 and middle school laws in 2006.

Difference between mean rating for state elementary school laws in 2003 and middle school laws in 2006. No change–weak: Equal mean rating (1–2). No change–strong: Equal mean rating (>2). New laws–weak: Mean higher for 2006 middle school laws (1–2). New laws–strong: Mean higher for 2006 middle school laws (>2). Weaker: Mean lower for 2006 middle school laws.

Absolute difference in average within-student change in BMI or probability of overweight/obesity, based on fixed-effect model, adjusted for locale and SES.

Students were estimated to have smaller increases in within-school purchasing of sweets if they resided in states with consistent laws from 2003 to 2006 (Supplemental Table 4). Associations between strong 2003 laws and changes in within-school purchasing behaviors were negative, as hypothesized, but not statistically significant. Likewise, categories of 2003 to 2006 law changes were associated with smaller increases in SSB purchasing, but associations were not statistically significant.

Discussion

In this longitudinal analysis, state competitive food laws were associated with lower BMI change and lower risk of remaining overweight or obese over time in a racially and socioeconomically diverse sample of 6300 adolescents across 40 states. Law strength and consistency emerged as 2 key factors that influenced the association. Adjusted BMI gain was lowest among adolescents exposed to laws that contained specific, required standards that were consistent as students progressed from fifth to eighth grade, whereas adolescents exposed to weaker laws over time experienced the same BMI change as those never exposed to competitive food laws.

Law strength and consistency are salient to ongoing attempts to improve nutrition content of school foods. The stringency of school nutrition standards has been a contentious topic among policymakers, and at the time of this study, the USDA was in the process of designing competitive food standards as part of the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010. Our results suggest that competitive food laws had a relatively weak association with BMI change if they contained diluted nutrition standards that were nonspecific or not required. Consistency of competitive food standards is critical, given that competitive food policies tend to be weaker at higher grade levels.44 Based on our results, elementary school laws may have a limited impact unless reinforced by strong codified laws at higher grade levels.

Interestingly, strong baseline state laws were associated with within-student BMI change and maintenance of overweight/obesity but not with incidence of overweight/obesity. This suggests that the association is not uniform across the BMI distribution. There could be heterogeneity in the impact of competitive food laws if, for example, some students compensate by adjusting their dietary behaviors outside of school. Future research could use alternative statistical methods (eg, quantile regression) to explore how the association between laws and weight change varies by baseline BMI. Another potential source of heterogeneity is student lunch source, as students who bring food from home may not benefit from competitive food laws as much as students who purchase school foods. Either scenario would have implications for policymakers by suggesting who benefits from competitive food laws and whether laws must be complemented by initiatives in other sectors to target other students.

The association between laws and changes in within-school dietary purchases were in the hypothesized direction, although not always statistically significant. This is not surprising for several reasons. Unlike BMI, purchasing data were self-reported and more vulnerable to measurement error,45 which may bias estimates toward the null. Different states with strong laws may target different food/beverage groups, further weakening the overall association between laws and specific food/beverage groups. Finally, questions about purchasing did not distinguish between specific types of foods, such as high-fat versus low-fat sweets, and questions measured frequency of intake but not extent of intake. Future research should use more precise dietary assessment instruments (eg, 24-hour recall) to examine the association between competitive food laws and consumption of specific foods, beverages, and nutrients.

Our analyses incorporated 6 different laws targeting competitive foods and beverages in different settings. The results thus support policy evaluations that concluded that policies were effective if they addressed all aspects of the school food environment.29,33,34 The caveat, however, is that within-state correlation between laws makes it impossible to disentangle the 6 laws to identify the source of any effects. The observational design precludes us from making any causal inferences, but even if one could conclude that laws caused lower weight gain, one could not determine if the cause was because of the laws’ cumulative impact or 1 law having an exceptionally strong impact. Another factor to consider is that laws on different governing levels were being implemented during the same year that eighth-grade ECLS-K data were collected. The Child Nutrition and WIC Reauthorization Act of 200446 and the Alliance for a Healthier Generation School Beverage Guidelines47 both required guidelines for competitive foods or beverages to be implemented during the 2006 to 2007 school year. Some local districts also implemented their own policies.48 Additional research is needed to determine if states with stronger laws were implementing federal or local policies more aggressively.

Other limitations should be considered when assessing these results. A large proportion of students were lost to follow-up between fifth and eighth grade, and those lost were more likely to be racial/ethnic minorities or of low SES. Future research should examine whether competitive food law effectiveness varies by race/ethnicity or SES. Several student sociodemographic characteristics varied across state law categories, as well. Although we used multiple statistical methods to control for such characteristics, unmeasured time-varying confounding factors cannot be ruled out. Physical activity was a potential confounder in analyses of law changes, as we could not control for it in these models owing to changes in activity measures across grades. We also were unable to assess whether any differences in weight gain are maintained during the summer when students are not in school. Finally, we did not analyze adherence to laws, although several studies have reported that state competitive food laws were associated with healthier school food environments.49–53

We also encourage future studies to examine whether students who reside in states with particularly stringent standards (eg, lower limits on fat or sugar content) experience less BMI change. Few states had such stringent standards in 2003, prohibiting us from using stricter criteria to define strong laws. As laws continue to evolve, future studies could compare BMI change in states with different standards.

Conclusions

Several features of this study (objective measures of height, weight, and codified laws; longitudinal design; mixture of methodologies) built on existing research and strengthened the evidence that competitive food laws may improve adolescent weight status. The results of this study clearly indicate that strength of language, comprehensiveness, and consistency of new competitive food standards will be imperative if the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010 is to have success in reducing adolescent obesity.

Supplementary Material

Glossary

- CI

confidence interval

- ECLS-K

Early Childhood Longitudinal Study–Kindergarten Class

- SES

socioeconomic status

- SSB

sugar-sweetened beverage

- USDA

US Department of Agriculture

Footnotes

Dr Taber contributed to the study conception and design, led the analysis, and led the drafting of the article; Drs Chriqui, Perna, Powell, and Chaloupka contributed to the study conception and design, the acquisition of data, and the drafting and revising of the article; and all authors approved the final version that is being submitted and take public responsibility for the results.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: Support for this study was provided by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation to the Bridging the Gap Program at the University of Illinois at Chicago (PI: Frank Chaloupka); grant number R01HL096664 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (PI: Lisa Powell); and contracts HHSN261201000350P and HHSN261201100522P from the National Cancer Institute to the University of Illinois at Chicago (PI: Jamie Chriqui). The views expressed herein are solely those of the authors and do not reflect the official views or positions of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the National Cancer Institute; or the National Institutes of Health. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

References

- 1.American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on School Health . Soft drinks in schools. Pediatrics. 2004;113(1 pt 1):152–154 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine Nutrition Standards for Foods in Schools: Leading the Way Toward Healthier Youth. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute of Medicine Committee on Prevention of Obesity in Children and Youth Preventing Childhood Obesity: Health in the Balance. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harkin T. Preventing childhood obesity: the power of policy and political will. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(suppl 4):S165–S166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murkowski L. Preventing obesity in children: the time is right for policy action. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(suppl 4):S167–S168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.US Department of Agriculture. Changing the Scene: Improving the School Nutrition Environment. 2000. Available at: www.teamnutrition.usda.gov/Resources/changing.html. Accessed June 15, 2011

- 7.US Department of Health and Human Services The Surgeon General's Vision for a Healthy and Fit Nation. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General; 2010 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity and trends in body mass index among US children and adolescents, 1999-2010. JAMA. 2012;307(5):483–490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reilly JJ, Kelly J. Long-term impact of overweight and obesity in childhood and adolescence on morbidity and premature mortality in adulthood: systematic review. Int J Obes (Lond). 2011;35(7):891–898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bibbins-Domingo K, Coxson P, Pletcher MJ, Lightwood J, Goldman L. Adolescent overweight and future adult coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(23):2371–2379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olshansky SJ, Passaro DJ, Hershow RC, et al. A potential decline in life expectancy in the United States in the 21st century. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(11):1138–1145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang YC, McPherson K, Marsh T, Gortmaker SL, Brown M. Health and economic burden of the projected obesity trends in the USA and the UK. Lancet. 2011;378(9793):815–825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization Obesity: Preventing and Managing the Global Epidemic. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flynn MA, McNeil DA, Maloff B, et al. Reducing obesity and related chronic disease risk in children and youth: a synthesis of evidence with ‘best practice’ recommendations. Obes Rev. 2006;7(suppl 1):7–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Summerbell CD, Waters E, Edmunds LD, Kelly S, Brown T, Campbell KJ. Interventions for preventing obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(3):CD001871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen DA, Scribner RA, Farley TA. A structural model of health behavior: a pragmatic approach to explain and influence health behaviors at the population level. Prev Med. 2000;30(2):146–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katz MH. Structural interventions for addressing chronic health problems. JAMA. 2009;302(6):683–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Larson N, Story M. The adolescent obesity epidemic: why, how long, and what to do about it. Adolesc Med State Art Rev. 2008;19(3):357–379, vii [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Terry-McElrath YM, Freedman-Doan P, Brenner JS. School Policies and Practices to Improve Health and Prevent Obesity: National Secondary School Survey Results, School Years 2006-07 and 2007-08. Vol. 1: Executive Summary. Ann Arbor, MI: Bridging the Gap Program, Survey Research Center, Institute for Social Research; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Larson N, Story M. Are ‘competitive foods’ sold at school making our children fat? Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(3):430–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turner L, Chaloupka FJ, Chriqui JF, Sandoval A. School Policies and Practices to Improve Health and Prevent Obesity: National Elementary School Survey Results: School Years 2006-07 and 2007-08. Chicago, IL: Bridging the Gap Program, Health Policy Center, Institute for Health Research and Policy, University of Illinois at Chicago; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Finkelstein DM, Hill EL, Whitaker RC. School food environments and policies in US public schools. Pediatrics. 2008;122(1). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/122/1/e251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act, Pub L No. 111-296. 2010

- 24.Finkelstein E, French S, Variyam JN, Haines PS. Pros and cons of proposed interventions to promote healthy eating. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(suppl 3):163–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fletcher JM, Frisvold D, Tefft N. Taxing soft drinks and restricting access to vending machines to curb child obesity. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(5):1059–1066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sturm R. Disparities in the food environment surrounding US middle and high schools. Public Health. 2008;122(7):681–690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang YC, Bleich SN, Gortmaker SL. Increasing caloric contribution from sugar-sweetened beverages and 100% fruit juices among US children and adolescents, 1988-2004. Pediatrics. 2008;121(6). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/121/6/e1604 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Briefel RR, Crepinsek MK, Cabili C, Wilson A, Gleason PM. School food environments and practices affect dietary behaviors of US public school children. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109(suppl 2):S91–S107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cullen KW, Watson K, Zakeri I. Improvements in middle school student dietary intake after implementation of the Texas Public School Nutrition Policy. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(1):111–117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dority BL, McGarvey MG, Kennedy PF. Marketing of food and beverages in schools: the effect of school food policy on students' overweight measures. J Public Policy Mark. 2010;29(2):204–218 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Foster GD, Sherman S, Borradaile KE, et al. A policy-based school intervention to prevent overweight and obesity. Pediatrics. 2008;121(4). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/121/4/e794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jaime PC, Lock K. Do school based food and nutrition policies improve diet and reduce obesity? Prev Med. 2009;48(1):45–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Raczynski JM, Thompson JW, Phillips MM, Ryan KW, Cleveland HW. Arkansas Act 1220 of 2003 to reduce childhood obesity: its implementation and impact on child and adolescent body mass index. J Public Health Policy. 2009;30(suppl 1):S124–S140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Woodward-Lopez G, Gosliner W, Samuels SE, Craypo L, Kao J, Crawford PB. Lessons learned from evaluations of California’s statewide school nutrition standards. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(11):2137–2145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van Hook J, Altman CE. Competitive food sales in schools and childhood obesity: a longitudinal study. Sociol Educ. 2012;85(1):23–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sherry B, Jefferds ME, Grummer-Strawn LM. Accuracy of adolescent self-report of height and weight in assessing overweight status: a literature review. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161(12):1154–1161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mâsse LC, Frosh MM, Chriqui JF, et al. Development of a School Nutrition-Environment State Policy Classification System (SNESPCS). Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(suppl 4):S277–S291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.National Cancer Institute. Classification of laws associated with school students. Available at: http://class.cancer.gov/About.aspx. Accessed May 18, 2011

- 39.Tourangeau K, Le T, Nord C. Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Kindergarten Class of 1998-99 (ECLS-K): Fifth-grade Methodology Report (NCES 2006-037). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tourangeau K, Le T, Nord C, Sorongon AG. Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Kindergarten Class of 1998-99 (ECLS-K): Eighth-grade Methodology Report (NCES 2009-003). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Grummer-Strawn LM, et al. CDC growth charts: United States. Adv Data. 2000;(314):1–27 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cole TJ, Faith MS, Pietrobelli A, Heo M. What is the best measure of adiposity change in growing children: BMI, BMI %, BMI z-score or BMI centile? Eur J Clin Nutr. 2005;59(3):419–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Available at: www.cdc.gov/brfss/. Accessed May 31, 2011

- 44.Chriqui J, Schneider L, Chaloupka F, et al. School District Wellness Policies: Evaluating Progress and Potential for Improving Children's Health Three Years After the Federal Mandate. School Years 2006–07, 2007–08 and 2008–09. Vol. 2 Chicago, IL: Bridging the Gap, Healthy Policy Center, Institute for Health Research and Policy, University of Illinois at Chicago; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Livingstone MB, Robson PJ. Measurement of dietary intake in children. Proc Nutr Soc. 2000;59(2):279–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Child Nutrition and WIC Reauthorization Act of 2004. Pub L No. 108-265. 2004

- 47.Alliance for a Healthier Generation. Competitive beverage guidelines. Available at: www.healthiergeneration.org/companies.aspx?id=1376. Accessed February 7, 2011

- 48.Story M, Kaphingst KM, French S. The role of schools in obesity prevention. Future Child 2006;16(1):109–142 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Kubik MY, Wall M, Shen L, et al. State but not district nutrition policies are associated with less junk food in vending machines and school stores in US public schools. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110(7):1043–1048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Long MW, Henderson KE, Schwartz MB. Evaluating the impact of a Connecticut program to reduce availability of unhealthy competitive food in schools. J Sch Health. 2010;80(10):478–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Phillips MM, Raczynski JM, West DS, et al. Changes in school environments with implementation of Arkansas Act 1220 of 2003. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2010;18(suppl 1):S54–S61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Samuels SE, Hutchinson KS, Craypo L, Barry J, Bullock SL. Implementation of California state school competitive food and beverage standards. J Sch Health. 2010;80(12):581–587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Taber DR, Chriqui JF, Powell LM, Chaloupka FJ. Banning all sugar-sweetened beverages in middle schools: reduction of in-school access and purchasing but not overall consumption. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(3):256–262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.