Abstract

Background

Previous studies document a mental health advantage in British Indian children, particularly for externalising problems. The causes of this advantage are unknown.

Methods

Subjects were 13 836 White children and 361 Indian children aged 5-16 years from the English subsample of the British Child and Adolescent Mental Health Surveys. The primary mental health outcome was the parent Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ). Mental health was also assessed using the teacher and child SDQs; diagnostic interviews with parents, teachers and children; and multi-informant clinician-rated diagnoses. Multiple child, family, school and area factors were examined as possible mediators or confounders in explaining observed ethnic differences.

Results

Indian children had a large advantage for externalising problems and disorders, and little or no difference for internalising problems and disorders. This was observed across all mental health outcomes, including teacher-reported and diagnostic interview measures. Detailed psychometric analyses provided no suggestion of information bias. The Indian advantage for externalising problems was partly mediated by Indian children being more likely to live in two-parent families and less likely to have academic difficulties. Yet after adjusting for these and all other covariates, the unexplained Indian advantage only reduced by about a quarter (from 1.08 to 0.71 parent SDQ points) and remained highly significant (p<0.001). This Indian advantage was largely confined to families of low socio-economic position.

Conclusion

The Indian mental health advantage is real and is specific to externalising problems. Family type and academic abilities mediate part of the advantage, but most is not explained by major risk factors. Likewise unexplained is the absence in Indian children of a socio-economic gradient in mental health. Further investigation of the Indian advantage may yield insights into novel ways to promote child mental health and child mental health equity in all ethnic groups.

Keywords: Cross-cultural comparison, British Indians, advantaged groups, information bias, minority ethnic mental health, externalising problems

Introduction

When seeking to improve the health of a population, investigating why some groups have a mental health advantage may provide valuable insights (Patel & Goodman, 2007). British Indian (henceforth ‘Indian’) children may be one such advantaged group. A recent systematic review found fairly consistent evidence of lower rates of common child mental health problems in Indian children, particularly for externalising problems (A. Goodman, Patel, & Leon, 2008).

Yet while previous studies report fewer problems in Indian children, none examines whether this reflects a real health difference. One important alternative is that the apparent Indian advantage reflects information bias due to systematic reporting differences across ethnic groups. Such cross-cultural differences have been suggested in comparisons across countries (e.g. Heiervang, Goodman, & Goodman, 2008) or between ethnic groups in Britain (e.g. Sonuga-Barke, Minocha, Taylor, & Sandberg, 1993). These issues are central to interpreting observed ethnic differences, but are rarely examined (A. Goodman, et al., 2008).

Moreover, all previous studies are largely descriptive – none make a detailed attempt to explain the Indian advantage. This is a major limitation because ethnicity is a non-homogenous construct, encompassing both personal ethnic identity but also structural factors such as socio-economic position (SEP) or societal racism (Nazroo, 1998). Observed ethnic differences should therefore be a starting point for further investigations of causal mechanisms. Such investigations need to measure potential mediators and confounders directly and to pay particular attention to adjusting for SEP, given the large ethnic differences in how SEP indicators are inter-related (Modood, et al., 1997)

This paper therefore uses two large British surveys which have previously documented a lower prevalence of ‘any mental disorder’ in Indians in univariable analyses (Green, McGinnity, Meltzer, Ford, & Goodman, 2005; Meltzer, Gatward, Goodman, & Ford, 2000). We examine how far this apparent Indian mental health advantage reflects a real health difference and, if so, what explains that difference. Specifically we examine:

Is there evidence of poor construct validity or information bias in the mental health measures collected in Indians?

Is the Indian mental health advantage consistently reported across informants and across mental health measures?

Can any real Indian advantage be explained by the child, family, school and area characteristics of the Indian children in the surveys?

This represents the first detailed investigation of these questions, and also the most comprehensive analysis to date of any ethnic difference in child mental health in Britain. In addressing these questions, we focus upon the comparison of Indians with White children because Whites are the ethnic group about whom most is already known. Whites are also the only ethnic group larger than Indians, making this the best-powered contrast possible.

Methods

Sample

The British Child and Adolescent Mental Health Surveys (B-CAMHS) of 1999 and 2004 were two nationally-representative surveys conducted in England, Scotland and Wales (Green, McGinnity, Meltzer, Ford, & Goodman, 2005; Meltzer, Gatward, Goodman, & Ford, 2000). Children were sampled from 5-15 years in 1999 and 5-16 years in 2004, using the Child Benefit Register as a sampling frame and with clustered sampling via postal sector. The primary caregivers (‘parents’) of selected children were approached to give written informed consent for face-to-face interview. With parental permission, the child’s teacher and children aged 11 or over were also approached.

As the Scottish and Welsh samples contained only six Indian children, we restrict our analyses to children from England. Between the two B-CAMHS surveys, 22 916 English children were selected and 15 823 (69.0%) participated, including 13 936 White and 413 Indian children. Of these, 13 868 White and 361 Indian children had complete data for our primary outcome, the parent Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire completed in English. These children form the study population for this paper. The White children were 50.8% male with a mean age of 10.2 years; their Indian counterparts were 52.5% male with a mean of 10.3 years. As for their parents, 94.5% of White parent informants were mothers, 4.3% fathers and 1.2% other informants. Among the Indian parents, 82.5% were mothers and 17.5% fathers.

B-CAMHS received ethical approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the Institute of Psychiatry, King’s College London, and the national Multi-Centre Research Ethics Committee for England, Scotland and Wales.

Parent-reported ethnicity

Parents report the child’s ethnic group using questions from the UK census. In B-CAMHS 1999 the ethnicity question included the categories ‘Indian’ and ‘White’. B-CAMHS 2004 retained ‘Indian’ as a single category but distinguished ‘White British’ (N=6787) and ‘White Other’ (N=134). To achieve comparability between the two surveys we combined these White groups for analysis. Our White comparison group is therefore largely but not wholly White British.

Mental health measures

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire

Participating parents, teachers and children completed the 25-item Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ: R. Goodman, 1997, 2001). The SDQ can be divided into ten ‘internalising’ items covering emotional and peer problems and ten ‘externalising’ items covering behavioural and hyperactivity problems (the remaining five items cover prosocial behaviour). Item response options are Not true, Somewhat true and Certainly true.

Parents in B-CAMHS had a choice of over 40 languages for completing the SDQ. Seventeen White parents (0.1%) and 42 Indian parents (10.2%) completed SDQs in non-English languages. Many of these translations have not been validated, however, and we therefore use only SDQs completed in English. We also excluded SDQs with missing subscale scores (<2% for all informants in both Indians and Whites).

DAWBA bands and clinical diagnoses

All participating parents, teachers and children were administered the Development and Well-being Assessment (DAWBA: R. Goodman, Ford, Richards, Gatward, & Meltzer, 2000). This is a semi-structured interview administered by lay interviewers to parents and children, with a briefer self-complete questionnaire for teachers. Interviews contain detailed fully-structured sections on all child emotional, behavioural and hyperactivity disorders. Computer algorithms can use these fully-structured sections to provide ordered categorical variables (‘DAWBA bands’) of the probability that a child had a given disorder. This paper uses eight DAWBA bands: the emotional, behavioural and hyperactivity parent DAWBA bands; the emotional, behavioural and hyperactivity teacher DAWBA bands; and the emotional and behavioural child DAWBA bands (the child DAWBA contains no hyperactivity section).

The fully-structured sections of the DAWBA are followed by open-ended questions where respondents are prompted to describe problem areas. Experienced clinicians then use the closed and open responses from all three informants to assign diagnoses according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV: American Psychiatric Association, 1994). These diagnoses have been shown to have good reliability and validity in British samples (Ford, Goodman, & Meltzer, 2003; R. Goodman, et al., 2000).

Covariates and conceptual model

Box 1 summarises our 46 covariates and how we conceptualise these as relating to ethnicity. Level 1 of our model consists of the most distal variables, namely area characteristics, school characteristics and family SEP. These correspond conceptually to traditional epidemiological confounders and capture social/structural aspects of ethnicity. By contrast, Level 2 and Level 3 capture personal ethnic identity, reflecting potentially distinctive ways of thinking and behaving. We hypothesised that these might mediate some or all of the Indian advantage.

Box 1. Child, family, school and area variables assessed.

|

Exposure of interest |

Ethnicity |

| [P] Indian vs. White | |

|

| |

|

A priori confounders |

[P] Child’s age |

| [P*] Child’s gender | |

| [I] Survey year (1999 vs. 2004) | |

|

| |

|

Level 1: area characteristics, school characteristics and family SEP |

Area characteristics |

| [I] Geographical region: North East; North West; Yorkshire & Humberside; East Midlands; West Midlands; East Anglia; London; South East; South West. | |

| [I] Metropolitan vs. non-metropolitan region | |

| [I*] Small area deprivation, from the 2004 English Indices of Multiple Deprivation (Noble, et al., 2004). | |

| School characteristics | |

| [I*] Ford Score, a predictor of the prevalence of mental health problems in a school (A. Goodman & Ford, 2008). | |

| Family SEP | |

| [P] Responding parent’s highest educational qualification: no qualifications [coded 1]; poor GCSEs (grades D-F) or equivalent [2]; good GCSEs (grades A-C) [3]; A-level [4]; diploma [5]; degree [6]. | |

| [P] Weekly household income: £0-99 [coded 0.5]; £100-199 [1.5]; £200-299 [2.5]; £300- 399 [3.5]; £400-499 [4.5]; £500-599 [5.5]; £600-769 [6.85]; £770 or over [8.5]. | |

| [P] Housing tenure: owner occupied; social sector rented; privately rented. | |

| [P] Occupational social class: I; II; III Non-manual; III Manual; IV; V; Never worked; Full- time student.† | |

| [P] Mother’s economic activity: full time employed; part-time employed; looking after home and family; unemployed; other. | |

| [P] Father’s economic activity: as for mother’s economic activity | |

|

| |

| Level 2: Family composition and family stress | Family composition |

| [P] Family type: two-parent; stepfamily; lone parent family | |

| [P] Parents married vs. cohabiting | |

| [P] Three-generation household: grandparent present vs. no grandparent present | |

| [P] Number of co-resident siblings | |

| [P*] Mother’s age at child’s birth | |

| Family stress | |

| [P*] Parent’s mental health, from the 12-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12: Goldberg & Williams, 1998).† | |

| [P*] Family functioning, from the general functioning subscale of the McMaster Family Activity Device (Miller, Epstein, Bishop, & Keitner, 1985).† | |

| [P] Family ever experienced parental separation : yes/no | |

| [P] Family ever experienced financial crisis: yes/no | |

| [P] Family member (not the child) ever had police contact: yes/no | |

| [P] Family ever experienced the death of a parent or sibling of the child: yes/no | |

|

| |

| Level 3: Child characteristics | Physical disorders† |

| [P] Neuro-developmental disorder: yes/no | |

| [P] Developmental problems or immaturity: yes/no | |

| [P] Common physical health disorder: yes/no | |

| [P] Rare physical health disorder: yes/no | |

| Stressful life events to child | |

| [P] Child ever experienced serious illness requiring hospitalisation: yes/no | |

| [P] Child ever experienced death of a friend: yes/no | |

| Substance use† | |

| [C] Regular smoking (≥1 cigarette a week): yes/no. | |

| [C] Frequency of alcohol consumption: less than once a fortnight; once a fortnight to once a week; twice a week or more. | |

| [C] Ever used illegal drugs: yes/no | |

| Academic abilities and difficulties | |

| [T*] Teacher-reported academic difficulties (range 0-9), created by summing the teacher’s response to question on the child’s ability in 1) maths, 2) reading 3) spelling. Each question had response options above average [coded 0]; average [1]; some difficulty [2]; or marked difficulty [3]. | |

| [P] Parent-reported learning difficulties: yes/no | |

| [P] Parent-reported dyslexia: yes/no | |

| [A*] Formal tests of reading ability, from the British Ability Scales, second edition (Elliott, Smith, & McCulloch, 1996); B-CAMHS 1999 only | |

| [A*] Formal tests of spelling ability, measured as for reading ability; B-CAMHS 1999 only | |

| Parent reward and punishment behaviours; B-CAMHS 1999 only | |

| [P] Frequency of praising child: never; seldom; sometimes; often. | |

| [P] Frequency of non-physical punishment: never; seldom; sometimes; often. | |

| [P] Frequency of smacking child: never; seldom; sometimes; often. | |

| [P] Ever hits or shakes the child: yes/no | |

| Relationships with relatives; B-CAMHS 2004, 11-16 year olds only | |

| [C*] Perceived social support (range 0-14), using seven questions from the 1985 Health and Lifestyle Survey (Cox, et al., 1987).† | |

| [C] Number of close relatives inside the home | |

| [C] Number of close relatives outside the home | |

| [C] How often child helps relatives: under once a month; once a month; once a week; daily. | |

|

| |

| Outcomes | Externalising problems |

| [P] Parent externalising SDQ score | |

| [T] Teacher externalising SDQ score | |

[P]=parent-reported; [T]=teacher-reported; [C]=child-reported; [A]=formal assessment; [I]=investigator-assigned.

=continuous variables.

=Further information in Electronic Appendix

A priori interactions

In B-CAMHS 1999, a marked SEP gradient in reading ability was observed in Whites but not in Indians (Maugham, 2005). We therefore tested for interactions between Indian ethnicity and area deprivation/family SEP to examine if this also applied to child mental health. We also tested for interactions with family type or living in three-generation households. We believed the circumstances surrounding different family compositions might differ by ethnic group, and therefore so too might the implications for child mental health. Moreover, family type has been shown to interact with ethnicity in predicting adult mental health in Britain (Nazroo, 1997).

Statistical methods

We conducted all data analysis using Stata 10.1, except the factor analyses which were performed in MPlus5. All analyses adjusted for the complex B-CAMHS survey design.

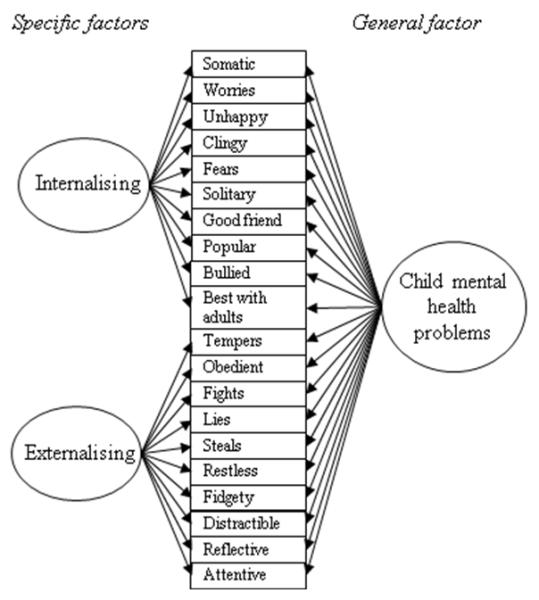

Factor analyses

We have previously demonstrated that the two-factor general-specific model shown in Figure 1 shows good fit to the parent, teacher and child SDQ data in the total B-CAMHS sample (A. Goodman, 2009). In this paper we used a multi-group confirmatory factor analysis (Brown, 2006) to test whether this factor structure was the same (invariant) across Indians and Whites. We performed the confirmatory factor analyses using a multivariate probit analysis with the extension for ordinal data (Muthen, 1984) and estimating model fit using the Weighted Least Squares, mean and variance adjusted estimator. We follow common practice in reporting multiple indices of fit. To consider a model as showing acceptable fit, we required a Comparative Fit Index >0.90; a Tucker Lewis Index >0.90; and a Root Mean Square Error of Approximation <0.08 (Brown, 2006).

Figure 1. Two-factor general-specific model used in multi-group confirmatory factor analyses of the SDQ.

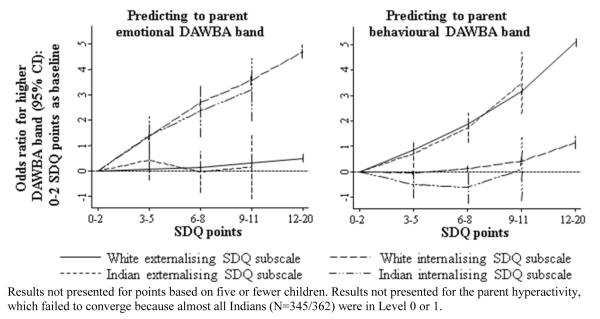

Comparing the SDQ with the DAWBA bands

We fitted a series of regression models with the internalising and externalising SDQ subscales as explanatory variables and the DAWBA bands from that same informant as an outcome (e.g. the parent SDQ to the parent DAWBA bands). We did this for the combined Indian and White sample, testing for interactions between ethnicity and 1) the internalising or 2) the externalising subscale. We thereby examined whether, for a given number of SDQ symptoms, Indians and White informants went on to report different levels of symptoms and impact in the DAWBA. If so, this would suggest a possible reporting bias on the SDQ. The underlying assumption is that although not a perfect ‘gold standard’, the far more numerous and more detailed DAWBA questions are less prone to bias than the brief SDQ (Heiervang, et al., 2008).

Multiple imputation for missing covariates

Some covariate data was missing systematically because it was only collected in one survey or because the teacher or child did not participate. Otherwise missing data was usually <1% and almost always <5%. We used multiple imputation (five imputations) to impute missing covariate values under an assumption of missing at random, using the MICE command in Stata10.1. When using covariates collected in only one survey, we restricted our analyses to that survey (e.g. B-CAMHS 1999 only).

Explaining the Indian advantage

To identify mediating or confounding variables which were important in explaining the Indian mental health advantage, we first fitted linear regression models with mental health (parent and teacher SDQ) as the outcome and with ethnicity, age, gender, survey year as explanatory variables. We then recorded how much the regression coefficient for White vs. Indian ethnicity changed after additionally adjusting for each covariate in turn. We treated most covariates as categorical variables, but used linear terms for the continuous variables (marked in Box 1). We interpreted movement towards the null (zero) in this ethnicity regression coefficient as meaning that the variable ‘explained’ some of the observed Indian advantage. We interpreted movement away from the null as the ‘unmasking’ of an even greater unexplained ethnic difference.

Table 1. Multi-group confirmatory factor analyses assessing measurement invariance between Indians and Whites, for the two-factor general-specific model displayed in Figure 1.

| Model | SDQ informant |

N | Comparative Fit Index |

Tucker Lewis Index |

Root Mean Square Error of Approximation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Two-factor; general- specific model; see Figure 1 |

Parent | 13 868 Whites, 361 Indian |

0.963 | 0.956 | 0.054 |

| Teacher | 10 775 Whites, 257 Indians |

0.987 | 0.985 | 0.056 | |

| Child | 5776 Whites, 156 Indians |

0.958 | 0.946 | 0.047 |

After examining these individual covariate effects, we fitted multivariable models adjusting for multiple variables simultaneously. First we entered variables with the largest individual effects in reducing the ethnicity regression coefficient. This represented an extreme case model showing how much of the Indian advantage was explained when adjusting only for variables which moved this advantage towards zero. We then entered variables with small individual effects (operationalised as changing the regression coefficient by <0.15) and finally variables which increased the regression coefficient by >0.15.

Results

Comparability of mental health measures across Indians and Whites

Indians made up 2.6% of the English B-CAMHS sample, similar to the figure of 2.4% in the 2001 census (National Statistics, 2003). In multi-group confirmatory factor analyses, the two-factor general-specific model shown in Figure 1 provided acceptable fit to the parent, teacher and child SDQs (Comparative Fit Index/Tucker Lewis Index>0.94, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation<0.06; Table 1). This provides evidence of measurement invariance with respect to ethnicity – i.e. that the loadings, thresholds and residual errors of each SDQ item are the same for Indians and Whites, and furthermore that these symptoms correspond to latent traits matching the hypothesised internalising and externalising constructs. This was also borne out by two-factor exploratory factor analyses imposing no prior structure upon the 20 items (see Electronic appendix).

There was also no evidence that Indians systematically over- or under-reported SDQ symptoms. Rather the Indian and White SDQ subscales generally had very similar odds ratios in ordered logistic regression models predicting to the DAWBA bands (see Figure 2). In only 1 of the 16 tests for interaction (eight DAWBA bands times two SDQ subscales) was there evidence (p<0.05) of an interaction between ethnicity and SDQ score. This interaction reflected an unexpected U-shape association between the parent internalising subscale and the parent behavioural DAWBA band in Indians (p=0.003; see Figure 2), but in the context of multiple testing is likely to be a chance finding.

Figure 2. Parent SDQ subscales as predictors of the parent DAWBA bands.

In summary, these psychometric analyses indicated that the internalising and externalising SDQ subscales had good construct validity in both Indians and Whites, and provided no evidence of ethnic reporting bias.

Consistency of the Indian advantage

In Indians the estimated prevalence of any mental disorder was 3.7% (95%CI 2.1%, 6.4%), substantially lower than the Whites prevalence of 10.0% (95%CI 9.4%, 10.5%). This difference was driven by Whites having more behavioural or hyperactivity disorders; for emotional disorders there was no evidence of a difference between the two groups (Table 2).

Table 2. Disorder prevalence (clinician-rated DAWBA) and parent, teacher and child SDQ scores for Indians and Whites types.

| White prevalence |

Indian prevalence |

Odds ratio & 95%CI for White vs. Indian ethnicity |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Clinician-rated DAWBA diagnosis (13 868 White, 361 Indian) |

Any mental disorder | 10.0 | 3.7 | 2.97 (1.65, 5.34)*** |

| Emotional disorder | 4.1 | 2.3 | 1.86 (0.89, 3.89) | |

| Behavioural disorder | 5.3 | 1.4 | 3.98 (1.70, 9.34)** | |

| Hyperactivity disorder | 2.4 | 0.3 | 8.46 (1.18, 60.56)* | |

|

White mean |

Indian mean |

Regression coefficient & 95%CI for White vs. Indian ethnicity |

||

|

Parent SDQ (13 868 White, 361 Indian) |

Total difficulty score | 8.31 | 7.44 | 0.87 (0.13, 1.61)* |

| Internalising problems | 3.33 | 3.54 | −0.21 (−0.67, 0.25) | |

| Externalising problems | 4.98 | 3.90 | 1.08 (0.73, 1.43)*** | |

|

Teacher SDQ (10 775 White, 257 Indian) |

Total difficulty score | 6.55 | 5.25 | 1.35 (0.58, 2.11)** |

| Internalising problems | 2.85 | 2.56 | 0.30 (−0.20, 0.80) | |

| Externalising problems | 3.70 | 2.69 | 1.05 (0.67, 1.43) *** | |

|

Child SDQ (5776 White, 156 Indian) |

Total difficulty score | 10.36 | 9.05 | 1.34 (0.49, 2.19)** |

| Internalising problems | 4.27 | 4.13 | 0.12 (−0.36, 0.59) | |

| Externalising problems | 6.08 | 4.92 | 1.22 (0.69, 1.76)*** |

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001.

Odds ratios/regression coefficients generated through logistic/linear regression, adjusting for age, gender and survey year.

The same pattern was observed for the parent, teacher and child SDQ scores (Table 2) and the parent, teacher and child DAWBA bands (see Electronic appendix). For the measures of behavioural/hyperactivity/externalising problems there was always strong evidence of an Indian advantage (usually p<0.001). This advantage reflected a shift to the left of the whole distribution of externalising scores, with more children receiving low scores and fewer receiving high scores. The magnitude of this shift was large, only slightly smaller than the difference between boys and girls – for example, on the parent SDQ the ethnic differences was 1.08 SDQ points and the gender difference 1.38 points. By contrast, there was little or no evidence of an ethnic difference for emotional/internalising problems (p≥0.05).

Stratified analyses indicated that these findings applied at all ages and for both boys and girls, with no evidence of an interaction between ethnicity and age or gender. The same was true after stratifying by mother vs. father for parent informant type; in all strata Indians continued to have a large advantage for externalising problems and little or no difference for internalising problems. The higher proportion of father informants among Indians therefore could not explain the observed Indian advantage.

Explaining the Indian advantage

Predictors of child externalising problems

Most variables in our conceptual model showed strong evidence of univariable associations with parent externalising SDQ scores (p<0.001). The exceptions were geographical region, metropolitan region, three-generation household and how often the child helped relatives; these four variables showed no evidence of an association (p>0.05).

Characteristics of Indians and Whites

Table 3 summarises the characteristics of Indians and Whites for selected variables. Full results are presented in the Electronic appendix, including externalising scores for each level. The Appendix also gives further details of the key findings summarised below.

Table 3. Indian and White participants for selected characteristics.

| Domain | Variable | Range/categories (see Appendix for numbers in each level) |

White percent or mean |

Indian percent or mean |

P for ethnic difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

A priori confounders |

Child’s sex | Male | 50.8 | 52.5 | 0.54(x) |

| Female | 49.2 | 47.6 | |||

| Child’s age | Range 5-16 years | m=10.2 | m=10.3 | 0.29(z) | |

| Family SEP |

Parent’s highest educational qualification |

No qualifications | 19.8 | 28.3 | <0.001(x) |

| Poor GCSEs | 14.9 | 17.7 | |||

| Good GCSEs | 31.3 | 18.9 | |||

| A-level | 10.7 | 6.8 | |||

| Diploma | 10.8 | 9.7 | |||

| Degree | 12.5 | 18.6 | |||

| Housing tenure | Owner occupied | 71.0 | 88.7 | <0.001(x) | |

| Social sector rented | 22.5 | 7.7 | |||

| Privately rented | 6.5 | 3.6 | |||

|

Family composition |

Family type | Two-parent family | 65.4 | 92.2 | <0.001(x) |

| Step family | 12.1 | 1.1 | |||

| Lone parent family | 22.4 | 6.7 | |||

| Family stress | Family functioning | Range 1-3.75 points | m=1.69 | m=1.80 | <0.001(z) |

| Child |

Teacher- reported academic difficulties |

Range 0-9 points | m=3.03 | m=2.71 | 0.05(z) |

|

Parent-reported learning difficulty |

No | 91.4 | 97.1 | <0.001(x) | |

| Yes | 8.6 | 2.9 | |||

|

Parent-reported dyslexia |

No | 96.4 | 99.5 | <0.001 (x) | |

| Yes | 3.6 | 0.5 | |||

|

Child, B- CAMHS 1999 only |

Formal reading ability |

Range −3.1 s.d. to +2.7 s.d.from average |

m=0.00 | m=0.13 | 0.24(y) |

|

Formal spelling ability |

Range −3.5 s.d. to +3.1 s.d.from average |

m=0.00 | m=0.32 | 0.001(y) |

(x)=chi-squared test for association; (y)=T-test (normally distributed continuous variables); (z)=Wilcoxon non-parametric test (non-normal continuous variables). Details on all covariates presented in the Electronic Appendix.

Many child, family, school and area characteristics showed major differences between Indians and Whites. Among the Level 1 variables, Indians were systematically disadvantaged for area deprivation, advantaged for housing tenure, concentrated at the extremes of the distribution for parent education, and similar for occupational social class and income. Further analyses revealed that household income, parent education and social class had a very similar relationship to each other in Indians and Whites. By contrast, the proportion of Indian and White home-owners was very similar in the most advantaged groups, but the steep SEP gradient in Whites was not observed in Indians. Indians also lived in more deprived areas at any given level of parent education, household income or occupational social class.

Among the Level 2 variables, two-parent families were substantially more common in Indians and less socio-economically differentiated. Indian families were also more likely to have a grandparent in the household. Most other family variables showed modest differences, with the exception of strong evidence of worse parent-reported family functioning in Indian families. This was unexpected, but further analyses revealed no evidence that the family functioning scale was an inappropriate or biased measure in Indians (see Electronic appendix).

Finally, Indian parents reported a lower prevalence of learning difficulties and dyslexia in their children. This was supported by evidence of Indians having fewer academic difficulties by teacher report and also doing better on the formal assessment of spelling (although not reading).

Key mediating and confounding variables: univariable analyses

As reported in Table 2, the ethnicity regression coefficient for the parent externalising score was 1.08 (95%CI 0.73, 1.43) after adjusting for age, gender and survey year. That is, the parent externalising score of Whites was an average of 1.08 SDQ points higher (less favourable) than Indians, corresponding to 0.28 standard deviations. The corresponding coefficient for teacher scores was 1.05 (95%CI 0.67, 1.43) or 0.26 standard deviations.

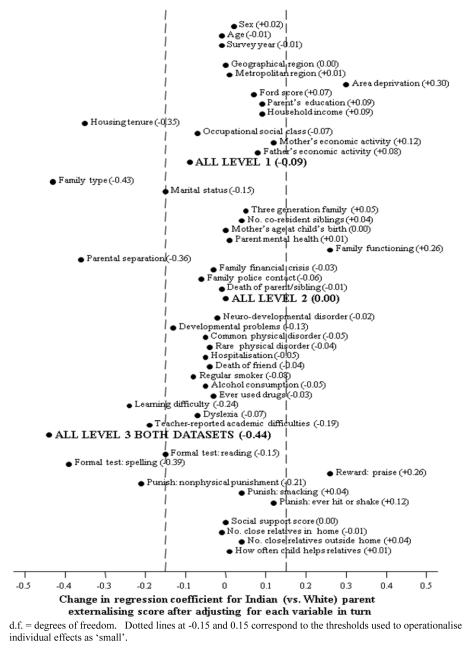

Figure 3 summarises how the parent regression coefficient changed after additionally adjusting for each covariate in turn. Large reductions in the regression coefficient (points on the left of the Figure) indicate variables which reduce the unexplained difference between Indians and Whites – that is, ‘explaining’ some of the Indian mental health advantage. Large increases in the regression coefficient (points on the right) indicate variables which increase the unexplained difference between Indians and Whites – that is, ‘unmasking’ an even greater Indian advantage. Points between the dotted lines indicate variables which we classified as having small individuals effects.

Figure 3. Change in the Indian (vs. White) regression coefficient for the parent externalising score after adjusting for each child, family, school and area characteristic in turn.

Among the Level 1 variables, housing tenure had a large individual effect in reducing (‘explaining’) the ethnic difference and area disadvantage had a large effect in increasing (‘unmasking’ a difference. Yet because these variables show a very different relation to other SEP indicators in Indians compared to Whites, it is more meaningful to examine the effect of adjusting simultaneously for all Level 1 variables. In fact this only reduced the ethnicity regression coefficient slightly, suggesting that confounding by area, school and family SEP variables cannot explain the Indian advantage.

Among the Level 2 variables, family type and parental separation had the largest effects in reducing the Indian advantage, while adjusting for the poorer family functioning of Indian families increased the unexplained Indian advantage. Among the Level 3 variables, only the academic ability variables consistently reduced the Indian advantage. Otherwise, most child factors had modest effects or (for the rewards/punishments variables) had moderate effects but in opposite directions. All these results were very similar when repeated using the teacher SDQ (see Electronic Appendix).

Key mediating and confounding variables: multivariable analyses

Our univariable analyses guided the multivariable analyses reported in Table 4. Our starting point, in the top line of the Table, was the regression coefficient for the Indian advantage adjusted only for age, sex and survey year. We then adjusted for the variables which the univariable analyses suggested were important in explaining the Indian advantage, namely the academic abilities variables (line 2 of Table 4) and family type/parent divorce (line 3). Next we entered the variables with small individual effects, grouping these as Level 1, 2 and 3 variables according to our conceptual model. Finally we entered family functioning, as a variable which seemed to unmask an even greater Indian advantage. For each line we present the magnitude of the regression coefficient as a percentage of the starting value.

Table 4. Ethnic differences in mean parent and teacher externalising SDQ score: adjusted regression coefficients for White vs. Indian ethnicity.

| Adjusted for: | Parent externalising score (13 868 White, 361 Indian) |

Teacher externalising score (10 775 White, 257 Indian) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted regression coefficient for Indian vs. White ethnicity |

Percent of initial value |

Adjusted regression coefficient for Indian vs. White ethnicity |

Percent of initial value |

|

| Sex, age and survey year | 1.08 (0.73, 1.43)*** | 100% | 1.05 (0.67, 1.43)*** | 100% |

| Plus academic abilities (teacher-reported academic difficulties, parent-reported learning difficulties, parent-reported dyslexia) |

0.80 (0.46, 1.15)*** | 74% | 0.78 (0.43, 1.12)*** | 74% |

| Plus family type and parental divorce | 0.51 (0.17, 0.84)** | 47% | 0.52 (0.18, 0.87)** | 50% |

| Plus Level 1 variables on area, school and family SEP (geographical region, metropolitan region, area deprivation, school quality, parent education, household income, housing tenure, social class) |

0.60 (0.25, 0.94)** | 56% | 0.58 (0.21, 0.95)** | 55% |

| Plus other Level 2 variables on family composition and stress (three-generation family, number of co-resident siblings, mother’s age, parent mental health, family financial crisis, family police contact, death of parent/sibling) |

0.69 (0.34, 1.04)*** | 64% | 0.66 (0.28, 1.04)** | 63% |

|

Plus other Level 3 child variables (neuro- developmental disorder, developmental problems, common physical health disorder, rare physical health disorder, child hospitalisation, death of a friend, smoking, alcohol, drug use) |

0.55 (0.19, 0.91)** | 51% | 0.57 (0.19, 0.95)** | 54% |

| Plus family functioning | 0.71 (0.35, 1.08)*** | 65% | 0.62 (0.24, 1.00)** | 59% |

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001.

Adjusting for academic abilities decreased the Indian advantage by about a quarter. There was little further change (-0.05 parent SDQ points and +0.01 teacher SDQ points) upon also adjusting for the formal tests of reading and spelling in B-CAMHS 1999 subset. Additionally entering family type decreased the regression coefficient for the Indian advantage to half its initial value, but it remained highly significant at p≤0.004. Further adjustment for other Level 1, Level 2 and Level 3 variables had only modest additional effects, and adding family functioning increased the coefficient somewhat. The final fully-adjusted values in the full population of Indians and Whites was 0.71 SDQ points (95% 0.35, 1.08; p<0.001) for parent externalising scores and 0.62 SDQ points (95%CI 0.24, 1.00; p=0.001) for teacher scores.

The parent and teacher externalising scores thus yielded similar substantive findings: adjusting for family type and academic abilities decreased the ethnicity regression coefficient somewhat but most of the difference remained unexplained. This was also replicated when the outcome was the child SDQ externalising score or any externalising disorder (see Electronic appendix). By contrast, internalising problems or disorders showed little or no evidence of an ethnic difference in multivariable models, consistent with their similarity in univariable analyses.

Interactions with ethnicity

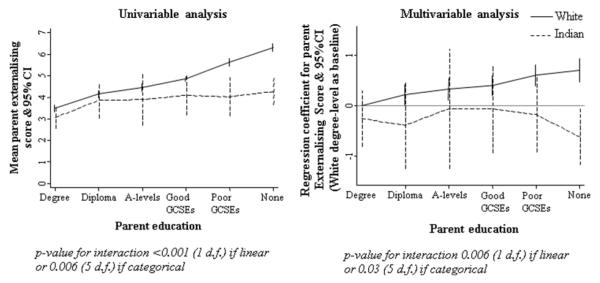

There was no evidence of an interaction between ethnicity and family type or three-generation family status (p≥0.17). By contrast, there was consistent evidence of an interaction between Indian ethnicity and area deprivation/family SEP. This was observed across all five measures in univariable analyses, and therefore could not be explained by ethnic differences in the inter-relationship between these SEP indicators. This interaction also persisted in fully-adjusted multivariable models, indicating that it was not explained by Indians’ child, family, school and area characteristics.

In all cases the interaction was such that the deprivation/SEP gradient of externalising problems was less marked in Indians than in Whites. The result was that among the most privileged families the mental health of Indians and Whites was similar, with the Indian mental health advantage largely confined to families facing socio-economic adversity.

Figure 4 illustrates this for parent education; for full results see the Appendix.

Figure 4. Parent externalising scores for Indians and Whites by parent education.

Discussion

This analysis of 13_868 White and 361 British Indian children aged 5-16 years provides strong evidence of a large Indian advantage for behavioural and hyperactivity problems. By contrast for emotional problems there was little or no evidence of difference. This pattern was observed with complete consistency across multi-informant clinical diagnoses; parent, teacher and child probability bands for disorder; and parent, teacher and child questionnaires (the SDQ). This consistency across outcomes and across informants provides important evidence that these measures provided valid and unbiased assessments, a conclusion supported by detailed psychometric analyses. As for why Indian have an advantage for externalising problems, a higher prevalence of two-parent families and higher academic abilities seemed to play some role. Yet even after adjusting for these and all the other covariates available, most of the Indian advantage remained unexplained. Likewise unexplained was the fact that the Indian advantage was particularly large in children from socially disadvantaged families. These results were replicated across parent-, teacher- and child-reported externalising scores and for externalising disorders, adding considerably to the confidence one can have in the findings.

The Indian advantage is confined externalising problems

These findings represent a major contribution to our understanding of child mental health in British Indians, Britain’s largest minority ethnic group. First, our demonstration that the British Indian advantage is confined to externalising problems is important for several reasons. For researchers, it suggests that future comparisons should always analyse externalising problems separately from internalising/emotional problems. For practitioners, it suggests that an apparent ‘under-representation’ of Indian children with behavioural and hyperactivity disorders in mental health clinics does not necessarily reflect unmet need. Instead it may reflect genuinely lower prevalence.

By contrast, Indian children do not seem to have fewer internalising/emotional problems. Nevertheless, it is worth stressing that there was certainly no evidence of any Indian disadvantage for internalising problems. This is important because some authors have hypothesised that a high value upon obedience and respect in Indian culture means that children are implicitly encouraged to express difficulties through internalising not externalising behaviours (Atzaba-Poria & Pike, 2007; Ghuman, 1999). Our findings provide evidence against this ‘redirection’ model, suggesting that the Indian advantage for externalising problems is not part of a zero-sum game in which difficulties are merely diverted rather than prevented.

The Indian mental health advantage is real

Crucial to interpreting this Indian advantage for externalising problems is the evidence that this reflects a real health difference. One key strength of our study is its population-based sampling, which avoids biases from ethnic differences in clinic referral patterns (Messent & Murrell, 2003). Another is that unusually rich mental health assessments allowed us to triangulate findings across informants and across different measures; use factor analyses to evaluate the hypothesised mental health constructs in both groups; and examine whether questionnaire measures showed evidence of reporting bias when judged against diagnostic interviews. By contrast, few previous studies have made any attempt to address the issue of information bias (A. Goodman, et al., 2008). Many studies could apply at least some of these techniques, however, and we hope that demonstrating them in this paper will encourage this.

Explaining the Indian advantage for externalising problems

Externalising problems have increased in Britain in the past 30 years and predict substantial adverse affects across multiple life outcomes (Collishaw, Maughan, Goodman, & Pickles, 2004). Understanding why rates of externalising problems remain low in British Indian children is therefore of great public health interest. It could illuminate ethnic differences related to other important social issues, such as the low rate of criminal offending reported by Indians (Sharp & Budd, 2005).

That family type mediates some of the Indian mental health advantage is not surprising; two-parent families are well-documented to be associated with better child mental health (McMunn, Nazroo, Marmot, Boreham, & Goodman, 2001) and to be more common in Indians than Whites (White, 2002). Indian family composition is also distinctive for its high proportion of three-generation households, but this was not important in explaining their mental health advantage. This was because, contrary to one previous study of British Indians and Pakistanis (Sonuga-Barke & Mistry, 2000), there was no evidence of a protective effect of living in three-generation households.

The only further substantial contribution in explaining the Indian advantage was their lower prevalence of academic difficulties. This is intriguing given that many leading prevention initiatives, including SureStart and the Healthy Schools program, aim to foster good child mental health by enriching educational experience. Understanding the Indian education advantage could therefore clarify a mechanism for promoting child mental health which is of great political interest. Yet unfortunately, while the higher educational attainment of Indians is well-described (Department for Education and Skills, 2005), little is known about its causes. This is because recent educational surveys either use meta-ethnic categories like ‘Asian’ (Peters, Seeds, Goldstein, & Coleman, 2007) or else oversampled only disadvantaged minority groups (Moon & Ivins, 2004).

We believe this exclusive focus upon minority ethnic problems is not justified, and that one key research question is why Indians have such high educational attainment. Another, related priority is investigating why this has a protective effect on mental health. Below-average academic ability is likely to have some direct effects (R. Goodman, Gledhill, & Ford, 2003), but may also partly be a marker for other protective parenting practices. Qualitative studies suggest these may include a strong cultural commitment to education and an emphasis upon respect and obedience towards adult authority figures (Dosanjh & Ghuman, 1996; Hackett & Hackett, 1994). These may have protective effects through pathways other than academic ability per se, such as increasing the congruence between expected behaviour at home and at school.

Understanding the Indian education advantage would therefore clarify an identified mechanism for the Indian mental health advantage and might also generate hypotheses regarding hitherto unidentified mechanisms. It might also shed light on the consistent and unexplained finding that the Indian advantage was particularly large in socio-economically disadvantaged families. We speculate that this may partly be explained by Indian families having a strong commitment to their child’s education regardless of their SEP. This is consistent with the flattening of the Indian SEP gradient for reading ability previously described in B-CAMHS 1999 (Maugham, 2005). It also resonates with sociological accounts of an ‘adaptation of middle-class values towards education by working-class South Asians‘ (Abbas, 2002, p.304).

Even if this hypothesis proves incorrect, the observed SEP-ethnicity interaction is of great potential interest. That there is little or no difference between Indians and Whites in high SEP groups provides some evidence against the Indian advantage being caused by protective gene alleles or by highly culturally-specific values. Instead the advantage may reflect attitudes and behaviours which have the potential to exist across ethnic groups, but which in Whites are currently largely confined to high SEP families. Further investigation could shed light on why the mental health of White children does show a strong SEP gradient and suggest how that gradient could be reduced.

Limitations and directions for future research

Investigating whether this SEP interaction is replicated in other studies is therefore one research priority. Also valuable will be further qualitative and quantitative studies which investigate the causes of the Indian education advantage; test our hypotheses regarding the importance of attitudes towards education; and examine other factors not measured in B-CAMHS. Examining novel factors is necessary because most of the Indian mental health advantage remained unexplained after adjusting for the many mental health risk factors which B-CAMHS did assess. Strikingly, in none of the multivariable models did the Indian advantage reduce by more than half or become non-significant at the 1% level. This included extreme case models adjusting only for variables which decreased the unexplained Indian advantage.

Examining novel factors is also necessary because B-CAMHS lacked information on potentially important variables such as acculturation/assimilation, religion or religiosity. B-CAMHS also lacked information which would permit examination of within-Indian heterogeneity (e.g. second vs. third generation children, or East African vs. non-East African migration to Britain). Finally, sample sizes for most ethnic groups were too small to allow detailed inter-ethnic contrasts. This prevented potentially informative contrasts with other groups who may have a mental health advantage (e.g. Black Africans (A. Goodman, et al., 2008)) and/or an education advantage (e.g. Chinese children (Department for Education and Skills, 2005)). Future studies oversampling these and other minority groups would have substantially greater scope for testing hypotheses using multi-ethnic comparisons.

Conclusion

British Indian children have a large advantage for externalising problems which cannot be explained by reporting bias. This advantage is partly mediated by family type and academic abilities, but most of the advantage is not explained by major risk factors. Likewise unexplained is the absence in Indian children of a socio-economic gradient in mental health. Greater understanding of these unexplained differences may help identify new ways to improve mental health and to promote mental health equity among children of all ethnicities.

KEY POINTS.

British Indian 5-16 year olds have far fewer externalising problems and disorders than British Whites, but little or no difference for internalising problems.

This pattern is reported by parents, teachers and children alike on both questionnaire and diagnostic interview measures, providing evidence against information bias; detailed psychometric analyses provide further evidence against bias.

Family type and academic abilities mediate part of this Indian advantage, but most is not explained by major risk factors.

Indian children do not show the marked socio-economic gradient in externalising problems which is observed in Whites.

Understanding the Indian advantage may suggest novel ways to promote child mental health and child mental health equity.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations

- B-CAMHS

British Child and Adolescent Mental Health Surveys

- DAWBA

Development and Well-Being Assessment

- OR

odds ratio

- SDQ

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire

- SEP

socio-economic position

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None

References

- Abbas T. The Home and the School in the Educational Achievements of South Asians. Race Ethnicity and Education. 2002;5:3. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV) American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Atzaba-Poria N, Pike A. Are ethnic minority adolescents at risk for problem behaviour? Acculturation and intergenerational acculturation discrepancies in early adolescence. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2007;25(4):527–541. [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research. Guilford Press; Guilford: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Collishaw S, Maughan B, Goodman R, Pickles A. Time trends in adolescent mental health. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004;45(8):1350–1362. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox BD, Blaxter M, Buckle ALJ, Fenner NP, Golding JF, Gore M, et al. The Health and Lifestyle Survey. The Health Promotion Research Trust; London: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Department for Education and Skills . Ethnicity and education: The evidence on minority ethnic pupils. Department for Education and Skills; Nottingham: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Dosanjh JS, Ghuman P. Child-rearing in ethnic minorities. Multilingual Matters Ltd; Avon: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott C, Smith P, McCulloch K. British ability scales, second edition: Administration and scoring manual. NFER; Windsor: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Ford T, Goodman R, Meltzer H. The British Child and Adolescent Mental Health Survey 1999: the prevalence of DSM-IV disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42(10):1203–1211. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200310000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghuman PAS. Asian Adolescents in the West. BPS Books; Leicester: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg DP, Williams P. A user’s guide to the General Health Questionnaire. NFER-Nelson; Windsor: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman A. Why do British Indians have a mental health advantage? University of London; London: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman A, Ford T. Validation of the Ford score as a measure for predicting the level of emotional and behavioural problems in mainstream schools. Research in Education. 2008;80(1):1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman A, Patel V, Leon DA. Child mental health differences amongst ethnic groups in Britain: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2008;8(1):258. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: a research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1997;38(5):581–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R. Psychometric properties of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40(11):1337–1345. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200111000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R, Ford T, Richards H, Gatward R, Meltzer H. The Development and Well-Being Assessment: description and initial validation of an integrated assessment of child and adolescent psychopathology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2000;41(5):645–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R, Gledhill J, Ford T. Child psychiatric disorder and relative age within school year: cross sectional survey of large population sample. BMJ. 2003;327(7413):472. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7413.472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green H, McGinnity A, Meltzer H, Ford T, Goodman R. Mental health of children and young people in Great Britain, 2004. Palgrave MacMillan; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hackett L, Hackett R. Child-rearing practices and psychiatric disorder in Gujarati and British children. British Journal of Social Work. 1994;24(2):191–202. [Google Scholar]

- Heiervang E, Goodman A, Goodman R. The Nordic advantage in child mental health: separating health differences from reporting style in a cross-cultural comparison of psychopathology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;49(6):678–685. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maugham B. Educational Attainments: Ethnic Differences in the United Kingdom. In: Rutter M, Tienda M, editors. Ethnicity and Causal Mechanisms. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- McMunn AM, Nazroo JY, Marmot MG, Boreham R, Goodman R. Children’s emotional and behavioural well-being and the family environment: findings from the Health Survey for England. Soc Sci Med. 2001;53(4):423–440. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00346-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer H, Gatward R, Goodman R, Ford T. Mental health of children and adolescents in Great Britain. The Stationery Office; London: 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messent P, Murrell M. Research leading to action: a study of accessibility of a CAMH service to ethnic minority families. Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2003;8(3):118–124. doi: 10.1111/1475-3588.00057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller I, Epstein N, Bishop D, Keitner G. The McMaster Family Assessment Device: reliability and validity. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 1985;11:345–356. [Google Scholar]

- Modood T, Berthoud R, Lakey J, Nazroo J, Smith P, Virdee S, et al. Ethnic Minorities in Britain: Diversity and Disadvantage. Policy Studies Institute; London: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Moon N, Ivins C. Parental Involvement in Children’s Education. Department for Education and Skills; Nottingham: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Muthen B. A General Structural Equation Model with Dichotomous, Ordered Categorical, and Continuous Latent Variable Indicators. Psychometrika. 1984;49(1):115–132. [Google Scholar]

- National Statistics Sex and age by ethnic group (Table S101) 2003 Retrieved 8th August 2008, from http://www.statistics.gov.uk/CCI/SearchRes.asp?term=s101&x=9&y=11.

- Nazroo JY. Ethnicity and mental health: findings from a National Community Survey. Policy Studies Institute; London: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Nazroo JY. Genetic, cultural or socio-economic vulnerability? Explaining ethnic inequalities in health. Sociology of health and illness. 1998;20(5):710–730. [Google Scholar]

- Noble M, Wright G, Dibben C, Smith G, McLennan D, Anttila C, et al. Indices of Deprivation 2004. Office of the Deputy Prime Minister; London: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Patel V, Goodman A. Researching protective and promotive factors in mental health. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36(4):703–707. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters M, Seeds K, Goldstein A, Coleman N. Parental Involvement in Children’s Education 2007. Department for Children Schools and Families; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sharp C, Budd T. Minority ethnic groups and crime: Findings from the Offending, Crime and Justice Survey 2003. 2005 Home Office Online Report 33/05. [Google Scholar]

- Sonuga-Barke E, Minocha K, Taylor EA, Sandberg S. Inter-ethnic bias in teachers’ ratings of childhood hyperactivity. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 1993;11(2):187–200. [Google Scholar]

- Sonuga-Barke E, Mistry M. The effect of extended family living on the mental health of three generations within two Asian communities. Br J Clin Psychol. 2000;39(Pt 2):129–141. doi: 10.1348/014466500163167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White A. Social Focus in Brief: Ethnicity 2002. Office of National Statistics; 2002. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.