Abstract

Objectives

Ultrasound contrast agents (UCAs) are intravenously infused microbubbles that add definition to ultrasonic images. Ultrasound contrast agents continue to show clinical promise in cardiovascular imaging, but their biological effects are not known with confidence. We used a cholesterol-fed rabbit model to evaluate these effects when used in conjunction with ultrasound (US) to image the descending aorta.

Methods

Male New Zealand White rabbits (n = 41) were weaned onto an atherogenic diet containing 1% cholesterol, 10% fat, and 0.11% magnesium. At 21 days, rabbits were exposed to contrast US at 1 of 4 pressure levels using either the UCA Definity (Lantheus Medical Imaging, Inc, North Billerica, MA) or a saline control (n = 5 per group). Blood samples were collected and analyzed for lipids and von Willebrand factor (vWF), a marker of endothelial function. Animals were euthanized at 42 days, and tissues were collected for histologic analysis.

Results

After adjustment for pre-exposure vWF, high-level US (in situ [at the aorta] peak rarefactional pressure of 1.4 or 2.1 MPa) resulted in significantly lower vWF 1 hour post exposure (P = .0127; Padj < .0762). This difference disappeared within 24 hours. Atheroma thickness in the descending aorta was lower in animals receiving the UCA compared to animals receiving saline.

Conclusions

Contrast US affected the descending aorta, as evidenced by two separate outcome measures. These results may be a first step in elucidating a previously unknown biological effect of UCAs. Further research is warranted to characterize the effects of this procedure.

Keywords: analysis of covariance, atherosclerosis, biomarkers, contrast media, endothelium, microbubbles, ultrasound

Ultrasound contrast agents (UCAs) are microbubbles encapsulating inert gases that serve to enhance the echogenicity of blood for cardiovascular imaging applications.1 The interaction of ultrasound (US) with circulating UCAs introduces the potential for unique biological effects. These bioeffects must be fully characterized and assessed before recommendations can be made regarding the appropriate uses of UCAs, and progress is urgently needed. The importance of medical imaging for early diagnosis is underscored by the fact that 2300 Americans die each day of cardiovascular disease by current estimates.2

Many in vitro and in vivo bioeffects of UCAs have been noted, including hemolysis,3 capillary rupture,4 endothelial cell damage,5 and elevations in troponin T, a biomarker of cardiac damage.6 Previous studies in our laboratory have demonstrated UCA-induced arterial endothelial and vascular smooth muscle injury7 and cardiac arrhythmias.8 These results suggest that the interactions of US with UCAs in the cardiovascular system may have important consequences, especially if exposure to contrast US hastens the onset or increases the severity of atherosclerosis in patients at risk.

To this end, we used a cholesterol-fed rabbit model to evaluate the biological effects of the UCA Definity (Lantheus Medical Imaging, Inc, North Billerica, MA) when used in conjunction with US to image the descending aorta. To assess these bioeffects, we chose to focus on the biomarker von Willebrand factor (vWF), a multimeric protein produced and stored within endothelial cells and secreted both across the basolateral endothelial membrane into the vascular intima9 and across the apical membrane into the vessel lumen, where it circulates in the blood.10 von Willebrand factor has a physiologic role in platelet plug formation during thrombosis.11 In addition to its physiologic function, elevated vWF is a biomarker of endothelial damage12 and a clinical predictor of adverse cardiovascular events.13 It is positively associated with risk for cardiovascular disease and cardiac death in epidemiological studies,14,15 and it has been shown to increase experimentally in hypercholesterolemic rabbits.16 We hypothesized that plasma vWF would increase when rabbits consumed a cholesterol-containing diet, and any further increase after US exposure would indicate endothelial damage due to the contrast US procedure.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Experimental Design

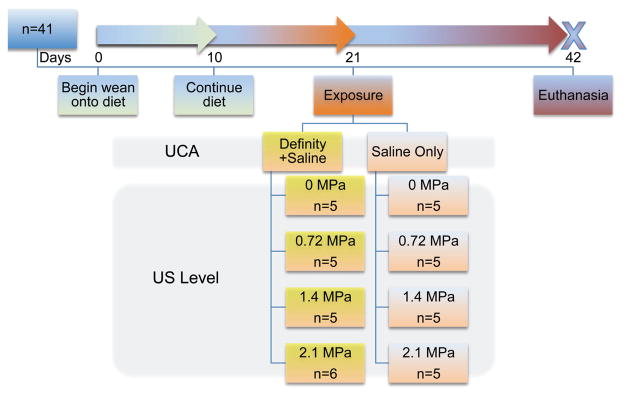

The experimental design is presented in Figure 1. After acclimation and consumption of a standard chow diet (Teklad 2031 Global High-Fiber Rabbit Diet; Harlan, Indianapolis, IN), male New Zealand White rabbits (n = 41; Myrtle’s Rabbitry, Thompson’s Station, TN) were randomized to experimental groups and weaned onto an atherogenic diet (5TZB; TestDiet, Richmond, IN) containing 1% cholesterol, 10% fat, and 0.11% magnesium over a 10-day period as previously described.17 The diet was optimized to elevate serum cholesterol and initiate the atherosclerotic process while minimizing side effects such as jaundice and anorexia. Weight and age (±SD) of the 41 rabbits at the beginning of the study (immediately prior to initiation of the atherogenic diet) were 3.3 ± 0.2 kg and 21.8 ± 1.0 weeks. Rabbits were exposed to US with or without the UCA at day 21 and euthanized at day 42. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign approved all procedures.

Figure 1.

Study design with 41 four-month-old male New Zealand White rabbits. Rabbits (n = 5–6 randomly assigned per group) were gradually introduced to an atherogenic diet consisting of 1% cholesterol, 10% fat, and 0.11% magnesium over 10 days and continued to consume the diet for 11 more days. On day 21, rabbits underwent the contrast procedure using either the ultrasound contrast agent (UCA) Definity in a saline vehicle or saline alone at 4 different ultrasound (US) pressure levels. Rabbits were euthanized at 42 days, and tissues were collected for histology.

Serial blood samples were collected from each rabbit at baseline (prior to initiation of the atherogenic diet), 2 weeks, 1 week, and 1 hour pre exposure and 1 hour, 24 hours, 48 hours, 1 week, 2 weeks, and 3 weeks post exposure. Blood samples were collected with heparinized syringes into heparinized tubes via the lateral saphenous vein while under restraint, centrifuged at 1380g for 10 minutes, and the plasma was aliquoted and frozen at −70°C.

Exposimetry

On day 21, 20 of the rabbits were infused with saline only, and 21 were infused with saline + the UCA (0.5 mL of Definity in 19.5 mL of saline). The infusion rate was 1 mL/min. The US exposure conditions for all 41 rabbits were: 3.2 MHz, 2-minute exposure duration at each of the 4 exposure sites, 10-Hz pulse repetition frequency, and 1.6-microsecond pulse duration at 4 separate in situ (at the aorta) peak rarefactional pressures, pr(in situ): 0 (sham), 0.72, 1.4, and 2.1 MPa.

The exposimetry and calibration procedures have been described previously in detail.18–23 Ultrasonic exposures were conducted using a focused f/3, 19-mm-diameter lithium niobate US transducer (Valpey Fisher, Hopkinton, MA). Water-based (degassed, 22°C) pulse-echo US field distribution measurements were performed according to established procedures22,24 and yielded a center frequency of 3.2 MHz, a fractional bandwidth of 11%, a focal length of 38 mm, a −6-dB focal beam width of 1.6 mm, and a −6-dB depth of focus of 27 mm.

An automated procedure, based on established standards,25 was used to routinely calibrate the US fields.22 Briefly, the source transducer’s drive voltage was supplied by a high-power pulse source (RAM5000; Ritec, Inc, Warwick, RI). A calibrated polyvinylidene difluoride membrane hydrophone (Y-34-6543; Marconi, Chelmsford, England) was mounted to the computer-controlled micropositioning system (Daedal, Inc, Harrisburg, PA). The hydrophone’s signal was digitized with an oscilloscope (500 MS/s; 9354TM; LeCroy, Chestnut Ridge, NY), the output of which was fed to the same computer (Dell Pentium II; Dell Corporation, Round Rock, TX) that controlled the positioning system. Offline processing (MATLAB; The MathWorks, Natick, MA) yielded the water-based peak rarefactional pressure, pr(in vitro). The mechanical index (MI) was also determined from the measurement procedure25: , where pr.3 is the derated (0.3 dB/cm-MHz) peak rarefactional pressure (in MPa), and fc is the center frequency (in MHz). The MI is reported because it is a regulated quantity26 of diagnostic US systems, and its value is available to system operators. Thus, there is value to provide the MI for each of our exposure settings in order to give general guidance to manufacturers and operators as to the levels we are using in this study. All 4 pr(in situ) levels were below the US Food and Drug Administration upper limit for diagnostic US of MI = 1.9 (see Table 1).26

Table 1.

Ultrasound Exposimetry for the 4 Exposure Groups

| Rabbit Group | pr(in vitro), MPa | AS, dB/cm-MHz | pr(in situ), MPa | MI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saline only | 0 | 0.79 ± 0.089 | 0 | |

| Saline only | 2.4 | 0.79 ± 0.089 | 0.75 ± 0.092 | |

| Saline only | 4.7 | 0.79 ± 0.089 | 1.5 ± 0.18 | |

| Saline only | 7.1 | 0.79 ± 0.089 | 2.2 ± 0.27 | |

| UCA | 0 | 0.85 ± 0.18 | 0 | |

| UCA | 2.4 | 0.85 ± 0.18 | 0.69 ± 0.16 | |

| UCA | 4.7 | 0.85 ± 0.18 | 1.3 ± 0.31 | |

| UCA | 7.1 | 0.85 ± 0.18 | 2.0 ± 0.47 | |

| Overall | 0 | 0.82 ± 0.15 | 0 | 0 |

| Overall | 2.4 | 0.82 ± 0.15 | 0.72 ± 0.14 | 0.64 ± 0.011 |

| Overall | 4.7 | 0.82 ± 0.15 | 1.4 ± 0.28 | 1.3 ± 0.041 |

| Overall | 7.1 | 0.82 ± 0.15 | 2.1 ± 0.42 | 1.8 ± 0.060 |

Values are mean ± SD where applicable. AS indicates attenuation slope; MI, mechanical index; pr, peak rarefactional pressure; and UCA, ultrasound contrast agent.

Independent calibrations were performed at least weekly on the 3.2-MHz focused transducer during the 7-week duration of the US exposure component of the experiment. The relative standard deviation (standard deviation/mean) of pr(in vitro) was 1.6% (n = 10). The pulse duration was also measured19 at each calibration, and its mean value (relative standard deviation) was 1.2 (0.6%) microseconds.

The calibration procedures were performed in degassed water, which minimally attenuates the US signal. In contrast, when US is used to image tissues in a live animal, the signal is attenuated as it passes through intervening tissue en route to its focus. Thus, estimation of the actual in situ (at the aorta) peak rarefactional pressure, pr(in situ), requires that attenuation be taken into account. A study was conducted to estimate the attenuation slope (AS, dB/cm-MHz) along the same in vivo tissue path as that of the single-element exposure path using the radio-frequency data from the Sonix RP (Ultrasonix Medical Corporation, Richmond, British Columbia, Canada) with the reference phantom technique.27 Three radiofrequency data sets were acquired at different locations and times. The first data set was acquired just before US exposure and UCA injection (data set I). Two minutes after injecting the UCA or saline, the second data set was recorded (data set II). Then, a 1-cm section of the descending aorta near the renal artery was exposed at 4 sites, 2 above the bifurcation to the renal artery and 2 below, with 2 mm between exposure sites. At the location of the last US-exposed site, a third data set was acquired (data set III). The in situ location of data set III was about 6 mm away from data sets I and II. A reference data set from a characterized physical phantom (AS = 0.67 dB/cm-MHz) was recorded using the same system settings. The AS was processed using the technique described by Yao et al27 and was then divided between saline-only (SA) and UCA rabbits to yield for the 3 data sets/locations (mean ± SD; dB/cm-MHz): ASSAI = 0.80 ± 0.097 and ASUCAI = 0.86 ± 0.16; ASSAII = 0.78 ± 0.094 and ASUCAII = 0.86 ± 0.16; and ASSAIII = 0.78 ± 0.079 and ASU-CAIII = 0.85 ± 0.24. Note the AS difference in data set I (saline-only versus UCA: 0.080 versus 0.086) even though this data set was acquired under the same rabbit conditions, that is, prior to injection of either saline or the UCA. Further note that the AS for saline-only remains about the same for all 3 data sets (0.80, 0.78, and 0.78) as does the AS for UCA (0.86, 0.86, and 0.85). Overall AS means were 0.79 ± 0.089 for saline-only and 0.85 ± 0.18 for UCA, yielding the individual pr(in situ) values listed for each exposure condition in Table 1. For practical purposes, by noting how close the individual ASs are between the saline-only and UCA rabbits (relative to their individual standard deviations), an overall AS value of 0.82 ± 0.15 dB/cm-MHz was used to estimate pr(in situ) at 3.2 MHz for a propagation distance of 4 cm, the pr(in situ). Therefore, the results reported and analyzed herein are the pr(in situ) values relative to the overall AS value of 0.82 dB/cm-MHz (Table 1).

Histology

All rabbits were anesthetized with ketamine hydrochloride and xylazine and then euthanized with carbon dioxide. The rabbit was placed in dorsal recumbency, and a ventral mid-line incision was made to expose the abdominal and thoracic cavities. The ribs were cut along the left lateral aspect of the sternum and manually spread open to allow visualization of the heart. A hemostat was clamped at the origin of the descending aorta. All tissues cranial to this site required to free the aorta were transected with scissors. The aorta, with heart attached, was slowly and carefully removed to the bifurcation of the aorta into common iliac arteries. Precautions were taken to gently remove the aorta in order to keep the endothelium intact. Surrounding fat was carefully removed, and the aorta was opened along one lateral aspect adjacent to the renal artery bifurcation. The liver was removed en masse and weighed. A small section of the liver was immediately frozen at −20°C for analysis of lipid content. Two sections of the aorta (the entire arch and a 2-cm section surrounding the renal artery at the site of US exposure) and a representative section of the left liver lobe were then placed in 10% formalin for 24 to 72 hours for subsequent pathologic evaluation.

After formalin fixation, sections of each tissue were trimmed off, placed in embedding cassettes, and subsequently processed, embedded in paraffin, and cut to 3-μm thickness. Sections were stained with hematoxylineosin. The aortic arch was cut transversely into 3 or 4 sections and placed in a cassette. The 2-cm section of the aorta (1 cm on either side of the renal artery) was cut longitudinally into 3 sections. Three edges were painted with tissue ink for orientation purposes and placed in another cassette. The representative section of the liver (including the central hepatic vein) was trimmed down to 1 × 1 cm and placed in a third cassette. One microscope slide was created from each cassette, resulting in 3 microscope slides per animal.

An atherosclerosis score was defined between 0 and 5 using the American Heart Association classification scheme for human atherosclerotic lesions.28 Score 0 = absence of atherosclerosis; score 1 = presence of isolated foam cells; score 2 = lipid accumulation mainly within the foam cells; score 3 = lipid accumulation within the foam cells and small pools of extracellular lipid; score 4 = intra-cellular lipid, lipid pools, and core of extracellular lipid; and score 5 = lipid core and fibrotic layer, or multiple lipid cores and fibrotic layer, or mainly calcified or fibrotic plaque. The atheroma thickness was measured using an ocular micrometer (Olympus America Inc, Center Valley, PA). The condition of the vascular endothelium was also assessed and categorized as mostly, partially, or minimally intact. The pathologist (author S.S.) assigned an atherosclerosis score, measured the atheroma thickness, and evaluated the endothelium for each tissue sample while blinded to exposure conditions.

Plasma vWF

Measurement of vWF was performed as previously described29 with some modifications. Briefly, a mouse anti-human monoclonal antibody to the amino-terminal trypsin- and plasmin-sensitive region of vWF (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) was diluted in carbonate buffer (pH 9.6), and 96-well microtiter plates were coated with 100 μL per well overnight at 4°C. The next day, the coating solution was emptied, and the plate was washed 3 times with 0.5% Tween 20 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Wells were then blocked with 0.2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS for 2 hours on an orbital shaker. After removing the block solution and washing, a vWF standard from human plasma (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA) was serially diluted and added to the plate. Rabbit plasma samples were diluted 1:100 in 0.05% BSA in PBS. The standard and all samples were plated in duplicate and incubated for 2 hours on an orbital shaker. The plate was emptied and washed again, after which a goat anti-human vWF polyclonal antibody (Abcam) diluted in 0.05% BSA in PBS was added as the sandwich antibody for 1 hour. After emptying and washing the plate, a donkey anti-goat horseradish peroxidase–conjugated polyclonal antibody was diluted in 0.05% BSA in PBS and added to the plate for 1 hour. The chromogenic substrate o-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride was combined with 0.05-mol/L phosphate-citrate buffer (pH 5.0) and 30% hydrogen peroxide. After washing, 100 μL of the o-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride solution was added to the plate for 30 minutes. The reaction was stopped by addition of 0.5-N sulfuric acid, and the plate was read at 490 nm. A linear standard curve was generated using the duplicate blanked readings from the serially diluted protein standard. Sample readings were interpolated into the standard curve to obtain concentration values. Average intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation (CVs) for rabbit plasma samples were 2.9% and 18.7%, respectively. Inter-assay precision was determined by incorporating a control rabbit plasma in each assay. This control was a large amount of plasma obtained in a single blood draw from an animal on a chow diet and was separated into many aliquots to validate inter-assay precision.

Plasma and Liver Lipids

Plasma low-density lipoprotein (LDL), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), and total cholesterol were analyzed using enzymatic colorimetric kits (Wako Chemicals, Richmond, VA). Human control sera (Wako Chemicals) were included in each assay for quality control. Average intra-assay CVs of control sera in each assay were 12% for the LDL assay, 4.0% for HDL, and 4.7% for total cholesterol. Average intra-assay CVs for rabbit plasma samples were 14% for the LDL assay, 4.0% for HDL, and 5.1% for total cholesterol.

Liver lipids were extracted using a modification of the Folch method.30 A 0.5-g section of liver was placed in a 1:1 mixture of chloroform and methanol, homogenized, and gravity filtered. The filtrate was immersed in a 0.29% sodium chloride solution, vortexed briefly, and centrifuged. The supernatant was then discarded, and the remainder was washed with 0.29% sodium chloride, transferred to a weighed test tube, evaporated, placed in a desiccator for 48 hours or longer, and weighed to determine total lipids.

Statistical Analysis

Effects of the UCA and pr(in situ) on vWF expression were evaluated via analysis of covariance31 for each of the post-exposure time points, with covariate adjustment for the vWF level 1 hour prior to exposure. The UCA was encoded as 0 = “saline only” or 1 = “saline + Definity.” The differences among the 4 levels of US were encoded as variables US1, US2, and US3 according to the orthogonal contrast matrix in Table 2. US1 is the contrast between −1 = low [pr(in situ) of 0 or 0.72 MPa] and 1 = high [pr(in situ) of 1.4 or 2.1 MPa] acoustic pressures; US2 is the contrast between 0 and 0.72 MPa; and US3 is the contrast between 1.4- and 2.1-MPa acoustic pressures. The analysis of covariance model for time point t was of the form:

with the above encoding, where vWFt is the vWF level at time t; vWFpre is the pre-exposure level; b0t is the regression coefficient for the intercept for time point t; b1t is the coefficient for the UCA at time t; b2t – b4t are the coefficients for US1, US2, and US3, respectively, at time t; and b5t is the coefficient for the effect at time t of the pre-exposure level of vWF. The model was run for time points t = 1 hour, 24 hours, 48 hours, 7 days, 14 days, and 21 days post exposure. For each of the 6 time points, the coefficients were estimated by least squares multiple linear regression. The statistical computations were performed using R.32 A conservative Bonferroni adjustment was used to account for repeated effect testing across 6 time points.

Table 2.

Orthogonal Contrast Matrix for Encoding 4 Levels of Ultrasound Acoustic Pressure in the Analysis of Covariance Model

| pr(in situ), MPa | US Encoding Variable

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| US1 | US2 | US3 | |

| 0 | −1 | −1 | 0 |

| 0.72 | −1 | 1 | 0 |

| 1.4 | 1 | 0 | −1 |

| 2.1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

Results

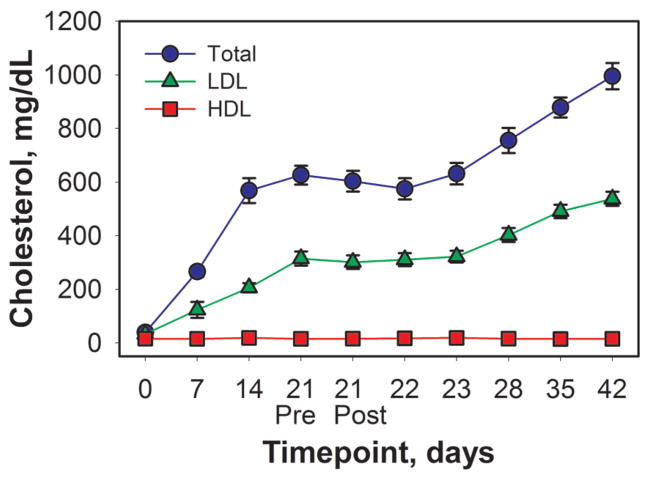

Plasma cholesterol levels began very low and increased rapidly after rabbits began consuming the cholesterol diet (Figure 2). At baseline, total cholesterol averaged 39 mg/dL, with approximately 27 mg/dL in LDL and 12 mg/dL in HDL. After consuming the cholesterol diet for 3 weeks, total cholesterol averaged 995 mg/dL, with 537 mg/dL in LDL and 15 mg/dL in HDL. Liver lipids for all rabbits averaged 137 ± 32 mg of lipid/g of liver (mean ± SD).

Figure 2.

Time course plot for plasma cholesterol. Plasma low-density lipoprotein (LDL), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), and total cholesterol were analyzed using enzymatic colorimetric kits. Human control sera were included in each assay for quality control. Serial blood samples were collected from each rabbit at the time points indicated; 21 Pre and 21 Post denote 1 hour pre and post exposure, respectively. Bars indicate SEM; n = 4 to 41 per time point.

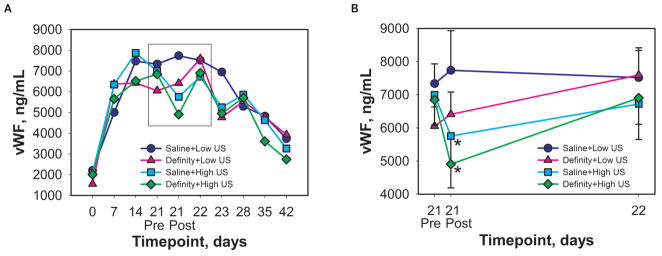

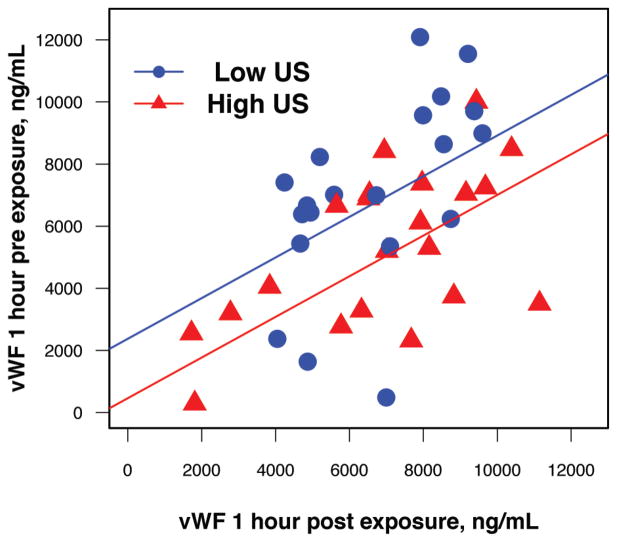

High-level US (1.4 or 2.1 MPa) resulted in significantly lower vWF 1 hour post exposure (P = .0127) than low-level US (0 or 0.72 MPa; Figure 3). Conservative Bonferroni adjustment for multiple time points gives an upper bound of Padj < .0762 for the overall significance of this difference. The other 2 US variables (contrasts between 0 and 0.72 MPa and between 1.4 and 2.1 MPa) were not significant (P > .1), thus supporting a reduction in the model for US effects to the contrast between low and high levels. Figure 4 demonstrates the correlation between vWF levels 1 hour post exposure and 1 hour pre exposure for low and high levels of US. The superimposed lines are the least squares lines for low and high levels of US, obtained from the fitted analysis of covariance model. The difference between the superimposed lines shows the US effect at 1 hour post exposure. This difference disappeared within 24 hours. The UCA was not a statistically significant factor in this analysis.

Figure 3.

Time course plots for plasma von Willebrand Factor (vWF) over the course of the entire study (A) and near the exposure time (B, enlargement of the boxed area in A and displaying a linear time course on the x-axis). von Willebrand Factor was assayed using a sandwich enzyme-linked immunoassay procedure. Serial blood samples were collected from each rabbit at the time points indicated. Low US indicates ultrasound exposure at 0 or 0.72 MPa; High US indicates 1.4 or 2.1 MPa. These pressure levels were combined for the purposes of statistical analysis. *Significantly different from High US (P = .0127; Padj < .0762). Bars indicate SEM; n = 10 or 11 per group.

Figure 4.

Scatterplot of von Willebrand Factor (vWF) levels 1 hour post exposure versus 1 hour pre exposure for low and high levels of ultrasound (US) exposure with fitted analysis of covariance lines for each group. The difference between the superimposed lines is the ultrasound effect at 1 hour post exposure.

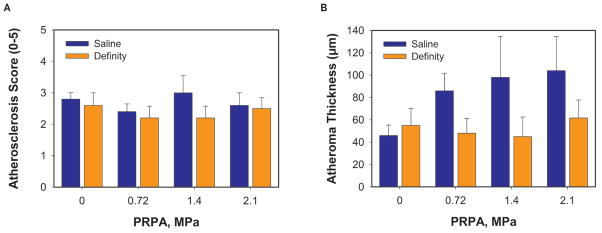

Animals receiving the Definity UCA displayed lower atheroma thickness in the descending aorta compared to animals receiving saline at the same US pressure level (Figure 5). The average atheroma thicknesses (mean ± SEM) were 46 ± 9 μm for saline at 0 MPa, 55 ± 16 μm for Definity at 0 MPa, 86 ± 16 μm for saline at 0.72 MPa, 48 ± 13 μm for Definity at 0.72 MPa, 98 ± 37 μm for saline at 1.4 MPa, 45 ± 18 μm for Definity at 1.4 MPa, 104 ± 31 μm for saline at 2.1 MPa, and 62 ± 18 μm for Definity at 2.1 MPa.

Figure 5.

Atherosclerosis score (A) and atheroma thickness (B) as a function of the in situ peak rarefactional pressure amplitude (PRPA). A 2-cm section of the abdominal aorta was excised from the area surrounding the renal artery and placed in 10% formalin for 24 to 72 hours. An atherosclerosis score was defined between 0 and 5 using the American Heart Association classification scheme for human atherosclerotic lesions. Score 0 = absence of atherosclerosis; score 1 = presence of isolated foam cells; score 2 = lipid accumulation mainly within the foam cells; score 3 = lipid accumulation within the foam cells and small pools of extracellular lipid; score 4 = intracellular lipid, lipid pools, and core of extracellular lipid; and score 5 = lipid core and fibrotic layer, or multiple lipid cores and fibrotic layer, or mainly calcific or mainly fibrotic. The pathologist assigned an atherosclerosis score and measured the atheroma thickness for each tissue sample while blinded to exposure conditions. Animals are grouped based on ultrasound exposure level and the ultrasound contrast agent. Bars indicate SEM; n = 5 or 6 per group.

Atherosclerosis scores were assigned by a pathologist blinded to the exposure conditions and are represented in Figure 5. The average atherosclerosis scores (mean ± SEM) were 2.8 ± 0.20 for saline at 0 MPa, 2.6 ± 0.40 for Definity at 0 MPa, 2.4 ± 0.25 for saline at 0.72 MPa, 2.2 ± 0.37 for Definity at 0.72 MPa, 3.0 ± 0.55 for saline at 1.4 MPa, 2.2 ± 0.37 for Definity at 1.4 MPa, 2.6 ± 0.40 for saline at 2.1 MPa, and 2.5 ± 0.37 for Definity at 2.1 MPa. Evaluation of the vascular endothelium is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Histologic Evaluation of the Vascular Endothelium at 42 Days

| pr(in situ), MPa | UCA | Mostly Intact | Partially Intact | Minimally Intact | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Saline | 4 | 1 | 5 | |

| 0 | Definity | 3 | 2 | 5 | |

| 0.72 | Saline | 1 | 4 | 5 | |

| 0.72 | Definity | 4 | 1 | 5 | |

| 1.4 | Saline | 2 | 3 | 5 | |

| 1.4 | Definity | 1 | 4 | 5 | |

| 2.1 | Saline | 4 | 1 | 5 | |

| 2.1 | Definity | 5 | 1 | 6 |

A 2-cm section of the abdominal aorta was excised from the area surrounding the renal artery and placed in 10% formalin for 24 to 72 hours. The condition of the vascular endothelium was assessed by a pathologist blinded to the exposure conditions and categorized as mostly, partially, or minimally intact. pr indicates peak rarefactional pressure; and UCA, ultrasound contrast agent.

Histologic evaluation of tissues excised from the rabbits at 42 days revealed profound diet-induced atherosclerotic changes. Analysis of the abdominal aorta revealed atherosclerotic damage, including atheroma, extracellular lipids, foam cells, calcification, and vacuolar changes. Of the 41 animals in the study, atheroma was noted in all animals, extracellular lipids in 24 animals, foam cells in all 41 animals, calcification in 1 animal, and vacuolar changes in 6 animals. Analysis of the aortic arch revealed similar findings. Atheroma was noted in all 41 animals, extracellular lipids in 35 animals, foam cells in all animals, calcification in 7 animals, and fibrosis in 5 animals. Damage to the liver included steatosis of hepatocytes in 40 animals, steatosis of Kupffer cells in 39 animals, steatohepatitis in 3 animals, and autolysis in 2 animals.

Discussion

Ultrasound has developed into an extremely versatile imaging modality both experimentally and diagnostically. As with any diagnostic technology, the balance of its risks and benefits must be weighed before a decision can be made regarding its safe use. While UCAs are valuable diagnostically, concerns have been raised regarding their safety. In addition to the numerous bioeffects observed experimentally, the US Food and Drug Administration issued an advisory in 2007 indicating that cardiopulmonary complications and death have been observed in patients soon after the administration of some approved UCAs, including Definity.1 The further development and use of UCAs is pending additional in vivo data regarding their safety.

Our objective was to determine if the interaction of US with UCAs in the vasculature impacts the onset or severity of atherosclerosis. In this study, we undertook a risk-based assessment of US bioeffects in a cholesterol-fed rabbit model. Plasma cholesterol levels increased dramatically (Figure 2), rising above 1500 mg/dL in some animals. Elevated plasma cholesterol is a substantial stress on the vascular system, and we assayed for vWF to determine the extent of this stress. The vWF biomarker could also potentially provide information about any additional stress of the US + UCA interaction on the vascular system. As we expected, vWF increased as a result of the vascular stress induced by the atherogenic diet and elevated cholesterol.

However, we also observed a decrease in plasma vWF after US exposure in animals exposed to US at 1.4 or 2.1 MPa compared to those exposed to 0 or 0.72 MPa, after adjustment for pre-exposure vWF levels (Figure 3). The decrease was observed when blood was drawn after exposure, although the pre- and post-exposure time points were less than 2 hours apart. This finding raised questions about any potential effect of US exposure on plasma vWF. After 24 hours, vWF returned to levels primarily determined by consumption of the atherogenic diet and continued a gradual decrease until the completion of the study, possibly due to progressive endothelial dysfunction.33

Interestingly, both decreased vWF and lower atheroma thickness were observed in the US + UCA groups. These results suggest an impact of US + UCAs on vascular integrity. There is a substantial body of literature documenting the potential of US to damage tissue, including US-induced lesions and hemorrhage in lung tissue34 observed in our laboratory. In the experiments described here, we may be seeing US-induced damage to the aorta, including the intima and endothelial monolayer. If that is so, some of the circulating vWF may be recruited to the site of damage in accordance with its coagulant role11 to form a platelet plug before the vessel is reendothelialized. It is unknown how plasma vWF levels change after such an event, preventing us from determining if the decrease represents an injury due to US + UCA exposure.

The post-exposure decrease in vWF is probably not due to reduced secretion by endothelial cells. The clearance time of unused plasma vWF in rabbits is 240 minutes,35 so a decrease in vWF would probably not reflect reduced secretion during the time frame of US exposure.

Animals receiving the UCA also displayed lower atheroma thickness in the descending aorta compared to animals receiving saline only at 3 weeks post exposure. These results may suggest that at the time of US exposure, the rabbits receiving the UCA experienced disruption of atheromas located at the site of exposure, while the saline-only groups did not. Thus, the artery walls in the UCA groups would represent only 3 weeks of growth and repair after US + UCA exposure, whereas the saline-only groups represent continual thickening throughout the study. The intima is the main driver of atheroma thickness,36 so US would presumably have affected the vascular intima.

We cannot rule out the possibility that less atheroma could simply be an artifact of tissue processing by the investigators or histotechnologist. However, tissue processing and histologic evaluation were blinded, and any changes in tissue morphology due to processing would not account for the results observed selectively in the US + UCA groups. We did not observe consistent long-term changes in the vascular endothelium across treatment groups on pathologic evaluation of the vascular endothelium at 42 days, but any damage to the endothelium would presumably have been repaired by then.37 Ultrasonic disruption of an atheroma could potentially lead to thrombosis and myocardial infarction, and our results could be a first step in uncovering a previously unknown bioeffect of UCAs. We should also consider the alternative possibility that this condition is a beneficial effect. The exposure-response relationship for the US + saline animals shown in Figure 5 could imply that US promotes deposition of atherogenic materials and consequent plaque growth, but coadministration of a UCA protects against this effect. The atheroma thickness for 0-MPa US was very similar among animals receiving the UCA or saline only, but the groups displayed a diverging trend on introduction of US. Other beneficial therapeutic uses of UCAs have been explored, including thrombolysis in myocardial infarction38 and gene or drug delivery.39 Our findings may lead to additional exploration of the beneficial effects of UCAs in diagnostic and therapeutic applications. While our results are preliminary, they highlight the need for further research investigating US-UCA interactions in vivo.

Cholesterol, liver lipid levels, and histologic findings underscore the impact of the atherogenic diet. The rabbit is a representative model of commonly identified changes in human atherosclerotic arteries. We were able to use a human classification scheme to evaluate the pathologic characteristics of atherosclerotic lesions in the rabbits, providing further justification for the model. We thus chose the rabbit as a straightforward and representative model for these experiments. We decided that all of the rabbits would be on only the atherogenic diet, allowing for an exposure-dependent effect if present, but with the largest possible number of animals per group.

In conclusion, we have described a risk-based assessment of contrast US bioeffects in a cholesterol-fed rabbit model. The contrast US procedure affected the vasculature as reflected by transient changes in plasma vWF and long-term differences in atheroma thickness. Future research is warranted to fully characterize the effects of this procedure, with the long-term goal of defining the specific conditions under which this procedure is safe for routine clinical use.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jennifer King, Michael Tu, Rami Abuhabsah, Matt Lee, Saurabh Kukreti, Shreyas Mathur, Michael Kurowski, and Provena Covenant Medical Center for their contributions. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R37EB002641.

Abbreviations

- AS

attenuation slope

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- CV

coefficient of variation

- HDL

high-density lipoprotein

- LDL

low-density lipoprotein

- MI

mechanical index

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- pr

peak rarefactional pressure

- UCA

ultrasound contrast agent

- US

ultrasound

- vWF

von Willebrand factor

References

- 1.Miller DL, Averkiou MA, Brayman AA, et al. Bioeffects considerations for diagnostic ultrasound contrast agents. J Ultrasound Med. 2008;27:611–632. doi: 10.7863/jum.2008.27.4.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2011 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123:e18–e209. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182009701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dalecki D, Raeman CH, Child SZ, et al. Hemolysis in vivo from exposure to pulsed ultrasound. Ultrasound Med Biol. 1997;23:307–313. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(96)00203-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller DL, Quddus J. Diagnostic ultrasound activation of contrast agent gas bodies induces capillary rupture in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:10179–10184. doi: 10.1073/pnas.180294397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kobayashi N, Yasu T, Yamada S, et al. Endothelial cell injury in venule and capillary induced by contrast ultrasonography. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2002;28:949–956. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(02)00532-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen S, Kroll MH, Shohet RV, Frenkel P, Mayer SA, Grayburn PA. Bio-effects of myocardial contrast microbubble destruction by echocardiography. Echocardiography. 2002;19:495–500. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8175.2002.00495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zachary JF, Blue JP, Miller RJ, O’Brien WD., Jr Vascular lesions and sthrombomodulin concentrations from auricular arteries of rabbits infused with microbubble contrast agent and exposed to pulsed ultrasound. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2006;32:1781–1791. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2005.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zachary JF, Hartleben SA, Frizzell LA, O’Brien WD., Jr Arrhythmias in rat hearts exposed to pulsed ultrasound after intravenous injection of a contrast agent. J Ultrasound Med. 2002;21:1347–1356. doi: 10.7863/jum.2002.21.12.1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Meyer GR, Hoylaerts MF, Kockx MM, Yamamoto H, Herman AG, Bult H. Intimal deposition of functional von Willebrand factor in atherogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:2524–2534. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.10.2524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sadler JE. Biochemistry and genetics of von Willebrand factor. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:395–424. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mannucci PM. Treatment of von Willebrand’s Disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:683–694. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra040403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Constans J, Conri C. Circulating markers of endothelial function in cardiovascular disease. Clin Chim Acta. 2006;368:33–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2005.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spiel AO, Gilbert JC, Jilma B. von Willebrand factor in cardiovascular disease: focus on acute coronary syndromes. Circulation. 2008;117:1449–1459. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.722827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kucharska-Newton AM, Couper DJ, Pankow JS, et al. Hemostasis, inflammation, and fatal and nonfatal coronary heart disease: long-term follow-up of the atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) cohort. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:2182–2190. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.192740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frankel DS, Meigs JB, Massaro JM, et al. Von Willebrand factor, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and risk of cardiovascular disease: the Framingham Offspring Study. Circulation. 2008;118:2533–2539. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.792986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haghjooyjavanmard S, Nematbakhsh M, Monajemi A, Soleimani M. von Willebrand factor, C-reactive protein, nitric oxide, and vascular endothelial growth factor in a dietary reversal model of hypercholesterolemia in rabbit. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2008;152:91–95. doi: 10.5507/bp.2008.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.King JL, Miller RJ, Blue JP, Jr, O’Brien WD, Jr, Erdman JW., Jr Inadequate dietary magnesium intake increases atherosclerotic plaque development in rabbits. Nutr Res. 2009;29:343–349. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Brien WD, Jr, Simpson DG, Frizzell LA, Zachary JF. Superthreshold behavior and threshold estimates of ultrasound-induced lung hemorrhage in adult rats: role of beamwidth. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control. 2001;48:1695–1705. doi: 10.1109/58.971723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O’Brien WD, Jr, Simpson DG, Ho MH, Miller RJ, Frizzell LA, Zachary JF. Superthreshold behavior and threshold estimation of ultrasound-induced lung hemorrhage in pigs: role of age dependency. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control. 2003;50:153–169. doi: 10.1109/tuffc.2003.1182119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Brien WD, Jr, Simpson DG, Frizzell LA, Zachary JF. Threshold estimates and superthreshold behavior of ultrasound-induced lung hemorrhage in adult rats: role of pulse duration. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2003;29:1625–1634. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Brien WD, Jr, Simpson DG, Frizzell LA, Zachary JF. Superthreshold behavior of ultrasound-induced lung hemorrhage in adult rats: role of pulse repetition frequency and exposure duration revisited. J Ultrasound Med. 2005;24:339–348. doi: 10.7863/jum.2005.24.3.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zachary JF, Sempsrott JM, Frizzell LA, Simpson DG, O’Brien WD., Jr Superthreshold behavior and threshold estimation of ultrasound-induced lung hemorrhage in adult mice and rats. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control. 2001;48:581–592. doi: 10.1109/58.911741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zachary JF, Frizzell LA, Norrell KS, Blue JP, Miller RJ, O’Brien WD., Jr Temporal and spatial evaluation of lesion reparative responses following superthreshold exposure of rat lung to pulsed ultrasound. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2001;27:829–839. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(01)00375-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raum K, O’Brien WD., Jr Pulse-echo field distribution measurement technique of high-frequency ultrasound sources. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control. 1997;44:810–815. [Google Scholar]

- 25.American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine, National Electrical Manufacturers Association. Standard for Real-Time display of Thermal and Mechanical Acoustic Output Indices on Diagnostic Ultrasound Equipment. Laurel, MD: American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine; Rosslyn, VA: National Electrical Manufacturers Association; 2004. Rev 2. [Google Scholar]

- 26.US Food and Drug Administration, Center for Devices and Radiological Health. Information for Manufacturers Seeking Marketing Clearance of Diagnostic Ultrasound Systems and Transducers. Silver Spring, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yao LX, Zagzebski JA, Madsen EL. Backscatter coefficient measurements using a reference phantom to extract depth-dependent instrumentation factors. Ultrason Imaging. 1990;12:58–70. doi: 10.1177/016173469001200105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. 7. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders Co; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith BW, Strakova J, King JL, Erdman JW, Jr, O’Brien WD., Jr Validated sandwich ELISA for the quantification of von Willebrand factor in rabbit plasma. Biomark Insights. 2010;5:119–127. doi: 10.4137/BMI.S6051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Folch J, Lees M, Sloane Stanley GH. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J Biol Chem. 1957;226:497–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Faraway JJ. Linear Models With R. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 32.R Development Core Team. R. A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2008. Version 2.11.1. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bonetti PO, Lerman LO, Lerman A. Endothelial dysfunction: a marker of atherosclerotic risk. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:168–175. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000051384.43104.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zachary JF, O’Brien WD., Jr Lung lesions induced by continuous- and pulsed-wave (diagnostic) ultrasound in mice, rabbits, and pigs. Vet Pathol. 1995;32:43–54. doi: 10.1177/030098589503200106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sodetz JM, Pizzo SV, McKee PA. Relationship of sialic acid to function and in vivo survival of human factor VIII/von Willebrand factor protein. J Biol Chem. 1977;252:5538–5546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tabas I, Williams KJ, Boren J. Subendothelial lipoprotein retention as the initiating process in atherosclerosis: update and therapeutic implications. Circulation. 2007;116:1832–1844. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.676890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fadini GP, Agostini C, Sartore S, Avogaro A. Endothelial progenitor cells in the natural history of atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2007;194:46–54. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hitchcock KE, Holland CK. Ultrasound-assisted thrombolysis for stroke therapy: better thrombus break-up with bubbles. Stroke. 2010;41(suppl):S50–S53. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.595348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Suzuki J, Ogawa M, Takayama K, et al. Ultrasound-microbubble-mediated intercellular adhesion molecule-1 small interfering ribonucleic acid transfection attenuates neointimal formation after arterial injury in mice. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:904–913. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.09.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]