Abstract

Optogenetic silencing strategies using light-driven ion fluxes permit rapid and effective inhibition of neural activity. Using rodent hippocampal neurons we show that silencing activity with a chloride pump can increase the probability of synaptically-evoked spiking in the period following light-activation, whereas this is not the case for a proton pump. This effect can be accounted for by changes to the GABAA receptor reversal potential and demonstrates an important difference between silencing strategies.

Multiple strategies have emerged for rapidly silencing the activity of neurons, all of which use the flux of various ion species in order to control the membrane potential and resistance1-3. Given that the same ion species are used by neurotransmitter receptors and channels, an important consideration is how optical silencing tools may interact with endogenous signalling systems4-6. A potential benefit of this approach is that it also offers the opportunity to use light-activated proteins as ion modulators with which to investigate cellular function7. The two most successful silencing strategies have used light-driven chloride (Cl−) pumps, which move Cl− into the cell2,8, and more recently proton (H+) pumps, which move protons out of the cell and thus generate a hyperpolarising effect9,11. Here we demonstrate that while a light-driven inward Cl− pump10 (Natronomonas pharaonis halorhodopsin, eNpHR3.0, ‘NpHR’) and a light-driven outward H+ pump9 (Archaerhodopsin-3 from Halorubrum sodomense, ‘Arch’) are both effective silencers of neural activity in mammalian neurons, they differ significantly in terms of their effect beyond the light-activation period. NpHR, unlike Arch, causes changes in the reversal potential of the GABAA receptor (EGABAA), which results in changes in synaptically-evoked spiking activity in the period following light-activation.

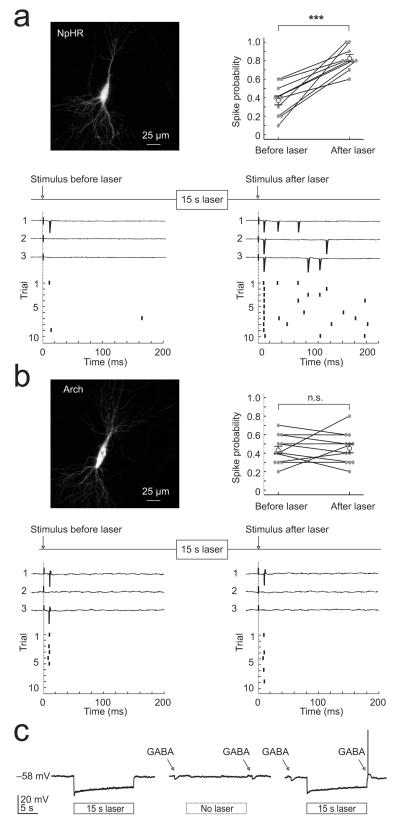

To compare the effects of optogenetic silencing strategies upon synaptically-evoked action potential activity, we performed cell-attached recordings from pyramidal neurons within CA1 and CA3 of rat hippocampal organotypic brain slices, which had been biolistically transfected with either eNpHR3.0-EYFP or Arch-GFP. Postsynaptic spikes were elicited by delivering brief electrical stimuli to the Schaffer collateral pathway. This stimulus recruits convergent monosynaptic and polysynaptic excitatory and inhibitory post-synaptic potentials, which exhibit mature properties at the time of our recordings (Supplementary Fig. 1 and 2; Supplementary Methods). Synaptically-evoked spike probability was measured before and after a 15 s period of laser-activation (532 nm, mean intensity 19.4 ± 3.4 mW mm−2). Separate whole cell recordings confirmed that these laser settings resulted in robust hyperpolarizing photocurrents in both NpHR- and Arch-expressing neurons, which were similar in amplitude (mean NpHR photocurrent 237 ± 46 pA; mean Arch photocurrent 235 ± 40 pA; Supplementary Fig. 3c). The photocurrents exhibited fast onset and offset kinetics as has been shown previously11,12 (Supplementary Fig. 3a,b), and were effective at inhibiting spiking activity during the period in which the laser was on (see below). However, we found marked differences in terms of how cells responded to synaptic input in the period following light-activation. In NpHR-expressing cells we found that the mean spike probability increased significantly from 0.37 ± 0.05 before laser-activation, to 0.82 ± 0.04 after laser-activation (n = 10 cells, P = 0.00015, paired t test; Fig. 1a). The mean stimulus-evoked spike rate (measured over 200 ms) also increased from 1.9 ± 0.3 Hz before laser-activation to 5.5 ± 0.9 Hz after laser-activation (P = 0.005, paired t test). This was in contrast to recordings from Arch-expressing cells, which had a comparable spike probability before and after laser-activation, even when the highest laser intensities were used (see example cell in Fig. 1b; range of 7.9 to 76.1 mW mm−2). For a population of Arch-expressing cells the spike probability before laser-activation was 0.43 ± 0.04 and the equivalent measure was 0.45 ± 0.05 after laser-activation (n = 12 cells, P = 0.74, paired t test; Fig. 1b). The mean stimulus-evoked spike rate was also stable for Arch-expressing cells at 2.15 ± 0.2 Hz before laser-activation and 2.3 ± 0.3 Hz after laser-activation (P = 0.64, paired t test).

Figure 1.

Optogenetic silencing strategies differ in their effects on synaptically-evoked spiking activity. (a) Top left, confocal image of a CA3 pyramidal neuron expressing eNpHR3.0-EYFP (‘NpHR’). Bottom, cell-attached recordings from this cell showing synaptically-evoked spiking before (left) and after (right) NpHR-activation (15 s, 532 nm, 7.9 mW mm−2). Spike probability was set to approximately 0.4 before laser-activation (measured over 10 trials). The ‘before’ stimulus was delivered 1250 ms before laser onset and the ‘after’ stimulus was delivered 250 ms after laser offset. Top right, summary of spike probability for NpHR cells (n = 10, error bars indicate s.e.m.). (b) Top left, a CA3 pyramidal neuron expressing Arch-GFP (‘Arch’). Bottom, cell-attached recordings from this cell showing synaptically-evoked spiking before (left) and after (right) Arch-activation (15 s, 532 nm, 76.1 mW mm−2). Top right, summary of spike probability for Arch cells (n = 12). All conventions as in ‘a’ (c) Perforated patch current clamp recording from a NpHR-expressing neuron. Laser-activation (10.9 mW mm−2 laser for 15 s) evoked a sustained hyperpolarizing response (left). In the absence of laser-activation, GABA puffs elicited hyperpolarizing responses (middle). However, the same GABA puff generated a depolarizing response and action potential when delivered 250 ms after laser-activation (right).

One explanation for the difference between the two light-activated pumps is that NpHR-activation results in an accumulation in intracellular Cl−, which then has sustained effects upon inhibitory synaptic transmission4-6. GABAA receptors (GABAARs) are primarily permeable to Cl− ions (approximately four times more permeable to Cl− than bicarbonate) and strong GABAAR activation is known to result in intracellular Cl− accumulation and a collapse in the Cl− gradient (but not the bicarbonate gradient), which causes depolarizing shifts in EGABAA13,14 . Our experiments in organotypic hippocampal slices and acute hippocampal slices (Supplementary Fig. 1) confirmed that Cl− influxes associated with GABAAR activation can result in significant depolarizing shifts in EGABAA. Furthermore, the larger the Cl− influx the more pronounced the effect upon EGABAA (Supplementary Fig. 1). As a first test of whether NpHR has sustained effects upon GABAergic transmission we performed current clamp recordings using the perforating agent gramicidin, which preserves intracellular Cl−. Under these conditions we found that a brief somatic puff of GABA (100 μM) normally generated a hyperpolarizing response, but when the same puff was delivered after a period of NpHR-activation, a depolarizing response and action potentials could be generated (n = 5 cells; Fig. 1c).

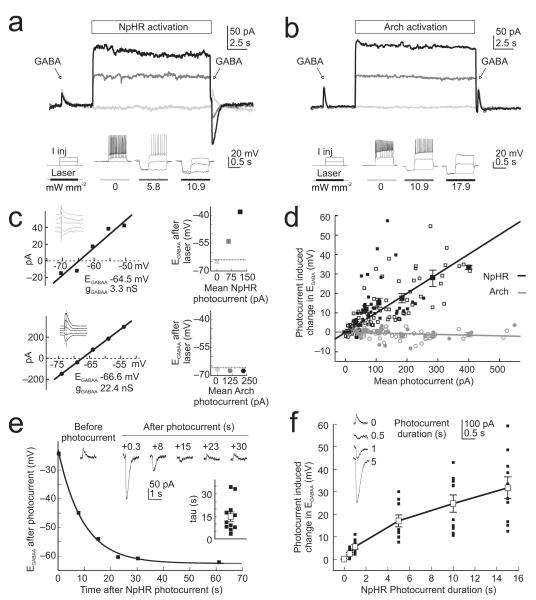

In order to systematically characterize the mechanisms that underlie the different effects of the two silencing strategies we performed a series of voltage clamp experiments to compare EGABAA before, and after, light-activation of the pumps. Resting EGABAA values did not differ between the NpHR-expressing (mean of −68.7 ± 1.2 mV, n = 18 cells) and Arch-expressing (mean of −68.5 ± 1.0 mV, n = 13 cells) neurons (P = 0.89, t test). However, we found that NpHR-activation for 15 s consistently changed the amplitude and/or polarity of GABAAR currents, such that GABAAR currents that were outward before laser-activation often became strong inward currents after laser-activation (measured 250 ms after laser offset; Fig. 2a), consistent with the light-driven accumulation of intracellular Cl−. This was not the case for Arch-expressing cells, which showed stable GABAAR currents across a range of photocurrents (Fig. 2b).

Figure 2.

A light-activated Cl− pump, but not a H+ pump, causes a sustained change in GABAergic transmission. (a) Top, gramicidin perforated patch voltage clamp recording from a neuron expressing eNpHR3.0-EYFP. GABAAR currents were measured before and after NpHR-activation using three different laser intensities: ‘zero’ (light grey), ‘intermediate’ (dark grey) and ‘higher’ (black). Note the change in direction of current flow through the GABAAR as a function of NpHR-activation. Bottom, laser intensities were selected by assessing their effectiveness in silencing spikes evoked by somatic current injection in current clamp (see Supplementary Information). (b) Recordings from a neuron expressing Arch-GFP. All conventions as in ‘a’. Note the consistent GABAAR current for different levels of Arch-activation. (c) Estimating the effects of photocurrents on EGABAA for the NpHR cell in ‘a’ (top) and Arch cell in ‘b’ (bottom). GABAAR IV plots (left) were used to calculate the resting EGABAA and GABAAR conductance (gGABAA), which were then used to estimate EGABAA for individual GABA puffs delivered after different mean photocurrents (right; symbol colours correspond to data in ‘a’ and ‘b’). (d) Summary of the change in EGABAA associated with different NpHR (black symbols) and Arch (grey symbols) photocurrents. Small empty symbols indicate data from organotypic hippocampal slices. Small filled symbols indicate data from acute hippocampal slices. Large symbols with error bars (s.e.m.) indicate combined population averages. e) Traces from a representative NpHR-expressing neuron showing GABAAR currents recorded at different times after the photocurrent, on different trials. EGABAA versus time after photocurrent is plotted for this cell and the recovery is well fitted by a single-exponential function. Inset plot shows the distribution of time constants of EGABAA recovery for all NpHR-expressing cells. (f) Traces from a representative NpHR-expressing neuron showing GABAAR currents recorded after photocurrents of different durations. Plot illustrates the change in EGABAA as a function of photocurrent duration for all NpHR-expressing cells.

The effect upon GABAAR currents was quantified by estimating EGABAA for individual GABA puffs and relating this to the size of the photocurrent (Fig. 2c; Supplementary Methods). This revealed a strong positive correlation between the size of the NpHR photocurrent and the change in EGABAA, (r = 0.70, P < 1×10−19, Pearson Correlation). The slope of the linear fit for the NpHR data indicated an 8.8 mV shift in EGABAA per 100 pA of mean photocurrent (Fig. 2d). Mean NpHR photocurrents of between 90 and 400 pA, which effectively blocked spiking activity evoked by somatic positive current injection (Fig. 2a, b and Supplementary Methods), generated an average EGABAA shift of 19.7 ± 1.7 mV (P < 1×10−14, t test). Modest mean NpHR photocurrents of between 25 and 50 pA also generated a significant change in EGABAA of 4.8 ± 1.0 mV (P = 0.0004, t test). In contrast, Arch-expressing cells exhibited much more stable EGABAA across a range of photocurrents (Fig. 2d); the slope of the linear fit for the Arch data was −0.4 mV per 100 pA of mean photocurrent, with a small negative correlation between Arch photocurrent and the change in EGABAA, (r = −0.2213, P = 0.023, Pearson Correlation). The slope of the linear fits for the two optical silencers were highly statistically different (P < 0.0001, Analysis of Covariance).

The experimental measurements of the effects of NpHR photocurrents upon EGABAA were consistent with a model we generated of Cl− homeostasis mechanisms, based on realistic cell parameters (Supplementary Fig. 4). To determine whether the effect of NpHR photocurrents upon EGABAA was evident in different experimental preparations, we examined excitatory neurons from mice that had received in vivo viral delivery of one of the optical silencers, via injections into the hippocampus (Supplementary Methods). These neurons, recorded in acute hippocampal slices, also showed a strong relationship between NpHR photocurrent and change in EGABAA (r = 0.50, P < 0.0001, Pearson Correlation; linear fit of 8.9 mV per 100 pA of photocurrent; n = 7 cells; Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 5a), which was statistically indistinguishable from neurons with plasmid-driven NpHR expression in organotypic slices (P = 0.89, Analysis of Covariance). As measurements of EGABAA made after a Cl− load reflect the rate of endogenous recovery mechanisms16, this indicates that NpHR photocurrents can overwhelm Cl− extrusion capacity to a similar degree in organotypic and acute slices (see Supplementary Fig. 1). Meanwhile, neurons with viral-expression of Arch showed stable EGABAA across a range of photocurrents (r = −0.07, P = 0.68, Pearson Correlation; linear fit of −0.2 mV per 100 pA of photocurrent; n = 6 cells; Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 5b). This was also - the case for non-expressing neurons recorded from regions of the brain slice with the highest virally-mediated Arch expression, indicating that Arch photocurrents do not affect EGABAA in a non-cell autonomous manner (Supplementary Fig. 6).

To further characterise the timescale of the effects of NpHR-activation we estimated EGABAA at different times after laser-activation. The rate of recovery of EGABAA had a time constant of 14.7 ± 3.2 s, on average (Fig. 2e and Supplementary Fig. 5c, d), which is similar to that seen after increases in intracellular Cl− generated by GABAAR activation13,14. Finally, varying the duration of the light-activation period revealed that changes in EGABAA were closely related to the duration of the photocurrent and were evident for relatively short photocurrents (Fig. 2f and Supplementary Fig. 5e, f). Significant positive shifts in EGABAA were detected following photocurrents of just 500 ms duration (2.41 ± 0.5 mV change in EGABAA, P = 0.0014, t test) and showed an incremental relationship with longer photocurrents. The depolarizing shifts in EGABAA that resulted from shorter periods of NpHR-activation were comparable to the shifts associated with prolonged activation of GABAARs (Supplementary Fig. 1), again supporting the conclusion that Cl−-dependent changes in EGABAA are a fundamental feature of mature GABAergic transmission. Finally, the NpHR-mediated shift in EGABAA was found to affect cells with different resting EGABAA, consistent with an overwhelming of endogenous Cl− regulation mechanisms (Supplementary Fig. 7).

These data show that silencing neural activity with a Cl− pump, but not a H+ pump, can alter GABAergic synaptic transmission beyond the period of silencing and in a manner that alters network excitability. The effects upon EGABAA are directly related to the size and duration of the Cl− photocurrent, with brief, small photocurrents generating the smallest shifts in EGABAA. This can account for a previous report that an earlier version of NpHR that generates smaller photocurrents did not affect GABAergic transmission6. For larger photocurrents, which offer more effective silencing10, the amplitude and duration of the photocurrent has a critical effect on the degree of EGABAA shift. In contrast, inhibitory photocurrents of comparable amplitude and duration achieved via a proton pump do not affect GABAergic synaptic transmission. Our data are consistent with reports of depolarizing shifts in the driving force for GABAARs in mature neurons, which result from an overwhelming of endogenous Cl− homeostasis mechanisms13,14. Previous work also established that bicarbonate (and therefore proton) gradients are maintained under conditions where Cl− gradients collapse, which is consistent with our observations with the two light-activated pumps13,14. This is believed to reflect the fact that whereas only transport mechanisms have been described for Cl−13,14, bicarbonate and pH gradients are kept more stable by a combination of transport mechanisms and a series of efficient intracellular and extracellular buffering mechanisms13,15. Our observations therefore establish an important difference between optical silencing strategies, which are relevant to ex vivo and in vitro experiments, and may be helpful in interpreting in vivo experiments. While both silencing strategies offer effective silencing they can result in different effects beyond the period of silencing – an important consideration for any experimental manipulation. Our work also confirms the use of light-activated proteins as ion modulators, which will be invaluable in exploring the role of key ion species in synaptic transmission, development and pathology.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Paul Bolam (MRC Anatomical Neuropharmacology Unit, Oxford University) for providing resources, and Karl Deisseroth (Stanford University) and Ed Boyden (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) for providing DNA constructs. We also thank Gero Miesenböck, Dennis Kätzel, Blake Richards and members of the Akerman lab for providing insightful comments and critically reading the manuscript. This work was supported by a grant from the Medical Research Council (G0601503) and the research leading to these results has received funding from the European Research Council under the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013), ERC grant agreement number 243273. J.V.R was supported by a Rhodes Scholarship.

References

- 1.Boyden ES, Zhang F, Bamberg E, Nagel G, Deisseroth K. Nat. Neurosci. 2005;8:1263–1268. doi: 10.1038/nn1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang F, Wang LP, Brauner M, Liewald JF, Kay K, Watzke N, Wood PG, Bamberg E, Nagel G, Gottschalk A, Deisseroth K. Nature. 2007;446:633–639. doi: 10.1038/nature05744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zemelman BV, Lee GA, Ng M, Miesenböck G. Neuron. 2002;33:15–22. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00574-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gradinaru V, Thompson KR, Zhang F, Mogri M, Kay K, Schneider MB, Deisseroth K. J. Neurosci. 2007;27(52):14231–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3578-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fenno L, Yizhar O, Deisseroth K. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2011;34:389–412. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-061010-113817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tønnesen J, Sørensen AT, Deisseroth K, Lundberg C, Kokaia M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2009;106(29):12162–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901915106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gourine AV, Kasymov V, Marina N, Tang F, Figueiredo MF, Lane S, Teschemacher AG, Spyer KM, Deisseroth K, Kasparov S. Science. 2010;329:571–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1190721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Han X, Boyden ES. PLoS One. 2007;2:e299. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chow BY, Han X, Dobry AS, Qian X, Chuong AS, Li M, Henninger MA, Belfort GM, Lin Y, Monahan PE, Boyden ES. Nature. 2010;463:98–102. doi: 10.1038/nature08652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gradinaru V, Zhang F, Ramakrishnan C, Mattis J, Prakash R, Diester I, Goshen I, Thompson KR, Deisseroth K. Cell. 2010;141:154–165. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mattis J, Tye KM, Ferenczi EA, Ramakrishnan C, O’Shea DJ, Prakash R, Gunaydin LA, Hyun M, Fenno LE, Gradinaru V, Yizhar O, Deisseroth K. Nat. Methods. 2011;9:159–72. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Madisen L, Mao T, Koch H, Zhuo JM, Berenyi A, Fujisawa S, Hsu YW, Garcia AJ, III, Gu X, Zanella S, Kidney J, Gu H, Mao Y, Hooks BM, Boyden ES, Buzsáki G, Ramirez JM, Jones AR, Svoboda K, Han X, Turner EE, Zeng H. Nat. Neurosci. 2012;10 doi: 10.1038/nn.3078. 1038/ nn.3078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Staley KJ, Proctor WR. J. Physiol. 1999;519:693–712. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0693n.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wright R, Raimondo JV, Akerman CJ. Neural. Plast. 2011:728395. doi: 10.1155/2011/728395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chesler M. Physiol. Rev. 2003;83:1183–221. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00010.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.