Abstract

Perinatal conditions make the largest contribution to the burden of disease in low-income countries. Although postneonatal mortality rates have declined, stillbirth and early neonatal mortality rates remain high in many countries in Africa and Asia, and there is a concentration of mortality around the time of birth. Our article begins by considering differences in the interpretation of ‘intervention’ to improve perinatal survival. We identify three types of intervention: a single action, a collection of actions delivered in a package and a broader social or system approach. We use this classification to summarise the findings of recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses. After describing the growing evidence base for the effectiveness of community-based perinatal care, we discuss current concerns about integration: of women’s and children’s health programmes, of community-based and institutional care, and of formal and informal sector human resources. We end with some thoughts on the complexity of choices confronting women and their families in low-income countries, particularly in view of the growth in non-government and private sector healthcare.

PERINATAL CONDITIONS CONTRIBUTE DISPROPORTIONATELY TO THE GLOBAL BURDEN OF DISEASE

The transition between the womb and the world is perilous. Each year over 6 million perinatal deaths occur worldwide (3.2 million stillbirths and 3 million early neonatal deaths; for definitions see table 1), 1 almost all of them in developing countries. 2 3 It is difficult to estimate numbers of perinatal deaths because they are often unobserved, unregistered and unclassified, but perinatal conditions are now thought to be the largest contributor to disease burden in low- and middle-income countries. The highest perinatal mortality rates (PMRs) are found in Africa and Asia (62 and 50 per 1000, respectively). 3

Table 1.

Definitions of indices used in the article, based on the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems: Tenth Revision (ICD-10) 63

| Perinatal period | Commences at 22 completed weeks (154 days) of gestation (the time when birth weight is normally 500 g), and ends 7 completed days after birth. Alternatively, a starting point of 28 completed weeks, or 1000 g birth weight, is often used for international comparisons, to account for the fact that an earlier cut-off may be inappropriate in many settings. |

| Live birth | The complete expulsion or extraction from its mother of a product of conception, irrespective of the duration of the pregnancy, which, after such separation, breathes or shows any other evidence of life, such as beating of the heart, pulsation of the umbilical cord, or definite movement of voluntary muscles, whether or not the umbilical cord has been cut or the placenta is attached; each product of such a birth is considered live born. |

| Stillbirth | Death prior to the complete expulsion or extraction from its mother of a product of conception, irrespective of the duration of pregnancy; the death is indicated by the fact that after such separation the fetus does not breathe or show any other evidence of life, such as beating of the heart, pulsation of the umbilical cord, or definite movement of voluntary muscles. Stillbirth occurs after the lower perinatal period cut-off described above. |

| Neonatal period | Commences at birth and ends 28 completed days after birth. Neonatal deaths (deaths among live births during the first 28 completed days of life) may be subdivided into early neonatal deaths, occurring during the first 7 days of life, and late neonatal deaths, occurring after the 7th day but before 28 completed days of life. |

| Stillbirth rate | Stillbirths per 1000 total births |

| Perinatal mortality rate | Stillbirths and early neonatal deaths per 1000 total births |

| Neonatal mortality rate | Neonatal deaths per 1000 live births |

The outlook is far from bleak. In the 1990s, child mortality declined in most parts of the world as public health interventions began to address the well-known causes of childhood illness: pneumonia, diarrhoea, malaria and vaccine preventable disease. 4 Stillbirths and neonatal deaths have declined more slowly and now outnumber later deaths of children under five. In 2001 there were 7.1 million stillbirths and neonatal deaths, compared with 6.7 million deaths of children aged 1–59 months.5

More than a third of stillbirths occur after events in labour that could be prevented through improved intrapartum care. 6 Neonatal deaths are mainly due to hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy, preterm birth, infection (a greater cause of late than early neonatal mortality) and congenital malformations. 7 Sixty million infants are born at home annually. 8 Perinatal survival depends largely on interventions to increase the supply, quality and demand for healthcare in the continuum from the antenatal to the postnatal period, with a special focus on the intrapartum period in which 2 million annual deaths occur. 9 10

Recent initiatives have demonstrated that perinatal survival can be increased in the poorest settings. We try to synthesise their findings in this article, and suggest that key health actions have been identified and their efficacy established. The important questions now lie in establishing the effectiveness of delivering them in low-resource settings.

WHAT DO WE MEAN BY INTERVENTION?

We find it useful to think of three types of intervention. First, a specific clinical, nutritional, behavioural or environmental action. Examples include taking a pill, measuring blood pressure or washing one’s hands. In a useful framework from discussions of maternal survival, Campbell and Graham call these single interventions. 11 The second type of intervention is a collection of actions which together form a package, 12 such as the 16 beneficial practices suggested in The Lancet series on neonatal survival. 13 The third type is the means of distribution by which single or packaged actions are delivered. We call this social and system intervention because some strategies aim for social change beyond the delivery of specific health actions. Imprecision about which of these types of intervention is being discussed can cause confusion when we try to weigh the evidence. For example, a randomised controlled trial (RCT) of antenatal corticosteroids in preterm labour is looking for proof of principle, the efficacy of a health action, while an evaluation of a training programme for health workers is looking for effectiveness of a system intervention.

SINGLE INTERVENTIONS

Table 2 summarises single health interventions that have been proposed to improve perinatal mortality in low-income countries. It includes interventions that unequivocally reduce PMR, such as maternal immunisation against tetanus and early and exclusive breastfeeding. It also includes interventions that are generally agreed to be beneficial, even though their effects on perinatal mortality may be uncertain. These include preventing iodine deficiency disorders, neural tube defects and haemorrhagic disease of the newborn, reducing the toll of smoking, indoor air pollution, syphilis, malaria and HIV, and giving women access to antenatal care.

Table 2.

Single interventions, divided into four categories on the basis of evidence of benefit to perinatal survival at a population level

| Interventions | Citations |

|---|---|

| Definitely reduce perinatal mortality at a population level | |

| Tetanus toxoid immunisation* | 13 14 30 64 65 |

| Identification of malpresentation, followed by appropriate action; particularly planned caesarean section for breech* | 13 17 66 |

| Antibiotics in preterm labour with rupture of membranes* | 13 16 17 21 64 67 |

| Antenatal corticosteroids for women at risk of or in preterm labour* | 13 16 17 64 68 |

| Clean delivery, cord cutting and cord care* | 13 14 16 64 |

| Resuscitation of infants who fail to establish breathing; with room air* | 13 14 16 17 64 69–71 |

| Prevention of neonatal hypothermia* | 13 14 17 64 72 |

| Early, followed by exclusive, breastfeeding* | 13 14 16 17 64 |

| Case management of neonatal sepsis or pneumonia* | 13 14 16 17 73 74 |

| Lack strong evidence of effect on perinatal mortality at a population level, but are unequivocally beneficial for other reasons | |

| Birth spacing | 14 – 17 |

| Maternal smoking cessation | 14 15 17 75 |

| Maternal smokeless tobacco cessation | 15 |

| Control of indoor air pollution | 15 17 |

| Maternal iodine supplements in areas of deficiency | 14 |

| Periconceptional folic acid supplementation* | 14 – 16 76 77 |

| Antenatal care: a limited number of visits (3–4) with specific activities | 14 – 16 78 |

| Screening for and treatment of maternal syphilis* | 13 14 17 21 79 |

| Prevention of malaria with insecticide-treated bednets | 14 17 21 64 80 |

| Chemoprophylaxis or intermittent presumptive treatment for malaria in pregnancy* | 13 14 16 17 21 64 81 |

| Calcium supplementation in deficient populations, for the prevention and management of pregnancy induced hypertension* | 13 16 21 |

| Presence of a familiar individual for support during labour | 19 |

| Prophylactic neonatal vitamin K to prevent bleeding due to vitamin K deficiency | 14 17 82 |

| Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV | 17 21 |

| Reduce perinatal mortality in principle, but lack evidence of effect at a population level | |

| Balanced protein–energy supplementation before or during pregnancy | 14 – 17 |

| Deworming during pregnancy in areas where helminthiases are endemic | 14 17 21 |

| Treating maternal periodontal disease | 21 |

| Identification and treatment of asymptomatic maternal bacteriuria* | 13 14 17 20 21 |

| Identification and treatment of maternal bacterial vaginosis | 14 17 21 83 84 |

| Doppler ultrasound monitoring in late pregnancy | 17 |

| Elective induction for post-term | 17 85 |

| Antenatal or intrapartum cardiotocography | 17 86 87 |

| Partography* | 13 17–19 |

| Delayed cord clamping | 14 88 89 |

| Topical application of emollients to infant body | 14 90 |

| Antiseptic applications to infant cord or body | 14 21 91 92 |

| Kangaroo mothercare for low birthweight infants* | 13 14 17 93 |

| Infant head or body cooling for hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy | 94 95 |

| Do not seem to reduce perinatal mortality at a population level, even though we thought they might | |

| Dietary advice | 96 |

| Iron supplements during pregnancy | 14 15 17 77 97 |

| Vitamin A supplements during pregnancy | 14 15 |

| Zinc supplements during pregnancy | 14 17 23 24 |

| Multiple micronutrient supplements during pregnancy | 14 15 22 25 |

| Routine antimicrobial prophylaxis during pregnancy | 98 |

| Antibiotics for prelabour rupture of membranes with intact membranes, or for known maternal group B Streptococcal colonisation | 14 17 99–101 |

Sixteen efficacious practices recommended in Darmstadt et al.13 Citations are key reviews and meta-analyses.

In addition to these unequivocally beneficial interventions, table 2 includes other interventions for which we lack evidence of effectiveness at a population level, and others for which there is sufficient evidence that they are not effective. For example, a substantial body of evidence suggests that balanced protein–energy supplementation for pregnant women will reduce PMR, 14–17 but we lack confirmation of this from effectiveness studies in low-resource populations. Some actions that are routine in higher-income countries may not have been evaluated against PMR in low-income settings, good examples being the use of partographs (tools to monitor, document and manage labour), and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria during pregnancy. 13 14 17–21 Some actions would be implemented in restricted populations. An example is head or body cooling for hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy, which is not advised outside specialist units. Another is kangaroo mother-care for low birthweight infants, which has so far generally been limited to healthcare facilities. Other examples include delayed cord clamping, topical antiseptics and emollients, the effects of which have not yet been clarified for home births in poor populations. These actions, which ‘should’ be effective but are not yet established as such, contrast with other actions, which ‘should’ be effective but appear not to be. Chief among these are micronutrient supplementation strategies: there is now relatively good evidence that vitamin A, zinc and multiple micronutrient supplements given during pregnancy to women in low-income countries will not reduce PMR at the population level. 14 15 17 22–25

PACKAGES OF INTERVENTIONS

Perinatal care in hospital involves the delivery of a package of interventions, 19 and so does extending care into communities. The components are sometimes, though not always, chosen on the basis of evidence of their efficacy. The package of family and community care interventions proposed in The Lancet Neonatal Survival Series includes ensuring hygiene and warmth, prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) of HIV, promotion of exclusive breastfeeding, recognition of danger signs and appropriate care-seeking and extra care for low birthweight babies. 9 13 Some governments have taken steps to locally adapt and systematise such packages. 26 Nepal’s community-based newborn care package, for example, involves counselling mothers for birth preparedness and giving information about danger signs and local antenatal services. It also involves postnatal visits to promote key home care practices, assess the mother and neonate, and refer them to facilities if needed. 27 However, the delivery and effectiveness of such intervention packages relies on functioning health systems – and particularly referral systems – and on the ability of health workers to reach the poorest mothers. Several reviews have confirmed that delivery remains a challenge, especially in settings where community health workers are volunteers operating with little training and supervision. 1 8 9 12 28 In other words, the components of packages may be fairly clear, but access and coverage are more complex, and it is here that the emphasis moves towards system change.

SOCIAL AND SYSTEM INTERVENTIONS

Table 3 summarises ways in which health actions have been stimulated through social or health system change. The cardinal approach has traditionally been – and should remain – improvement in the quality and reach of health services. Speed and effectiveness are particular challenges. The goal is skilled attendance at birth by an appropriately trained and supported health worker, with access to basic and comprehensive emergency obstetric care. 11 29 In settings with high levels of home births and limited use of health services, however, infrastructural, human resources and training limitations make this a long-term rather than a short-term aim. 30 Second, it seems that it is not just a matter of training health workers. A recent before-and-after evaluation of a training programme for the WHO Essential Newborn Care course, administered to birth attendants in six countries with high levels of home births, failed to show an effect on the risk of perinatal or early neonatal death (RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.70 to 1.02 and RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.22, respectively). There did seem to be a reduction in stillbirths (RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.54 to 0.88), but we should be circumspect about the potential for saving lives at scale. 31

Table 3.

Social or system interventions, divided into three categories on the basis of evidence of benefit to perinatal survival at a population level

| Interventions | Citations |

|---|---|

| Definitely reduce perinatal mortality at a population level | |

| Education for women | 14 |

| Birth preparedness on the part of women and their families: finances, registration, emergency plan | 14 17 |

| Promotion of birth preparedness and care-seeking by community health workers | 8 |

| Skilled care at delivery (‘skilled birth attendance’) | 8 14 16 102 103 |

| Institutional delivery where basic emergency obstetric care is available and comprehensive care is available through a transfer system | 12 17 102 |

| Home visits after delivery by community health workers (government or non-government) | 14 104 |

| Community mobilisation initiatives to build awareness of perinatal health and link families and health facilities | 105 |

| Lack strong evidence of effect on perinatal mortality at a population level, but are unequivocally beneficial for other reasons | |

| Institutional perinatal care audit | 12 106 |

| Elimination or reduction of user fees | 107 |

| Counting perinatal deaths: strengthening systems to report stillbirths and neonatal deaths | 108 109 |

| Reduce perinatal mortality in principle, but lack evidence of effect at a population level Training and support for traditional birth attendants | 8 14 |

| Task shifting providers of obstetric care | 19 |

| Transport systems for access and emergency transfer | 105 |

| Maternity waiting homes | 105 110 |

| Conditional cash transfers or voucher systems for maternity care | 111 |

| Training health workers in essential newborn care | 31 |

Citations are key reviews and meta-analyses.

Two other approaches look promising, both of them community-based. The first is home visits by either non-government,32 33 or government,34–36 community health workers. The second involves mobilisation interventions with community groups. In the first example, health workers make antenatal and early postnatal visits to discuss birth preparedness with women and check for problems in their newborn infants. The options are then to refer 33 or to provide some management at home. Specific options include resuscitation 32 34 and the administration of parenteral antibiotics. 32 Trials of such home-based newborn care have shown significant reductions in neonatal mortality, 32 34 36 although not necessarily in stillbirths. A good example is the work of the Society for Education, Action and Research in Community Health (SEARCH) in Maharashtra, India. From the early 1990s, SEARCH developed a home-based care package in which community-based non-government health workers were trained to provide health education and identify pregnancies. They visited women during pregnancy and after delivery, administered neonatal vitamin K injections and checked up on infants over the neonatal period. They were also trained to identify and resuscitate infants who did not initiate breathing, identify and advise on low birth weight and treat suspected infection with oral and intramuscular antibiotics. The programme, evaluated through a controlled trial, reduced neonatal mortality by about 70% (95% CI 59% to 81%) over a decade. 32 37 Another home-based care package, tested in the Projahnmo cluster-RCT (cRCT) in Bangladesh, found a 34% reduction in neonatal mortality in the home care arm during the last 6 months of the study (RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.47 to 0.93). 34 Finally, a controlled before- and-after study evaluated the impact of newborn care training for ‘lady health workers’ and traditional birth attendants (‘dais’) in rural Pakistan, and found a 34.6% reduction in the PMR in intervention areas. 36 Home-based care is now being incorporated in government healthcare strategies in countries such as India.

The second approach involves community mobilisation activities in which local women’s groups identify their own perinatal problems and develop strategies to address them. Two cRCTs in hard-to-reach populations have shown 30–45% reductions in neonatal mortality in areas where women’s groups met regularly to discuss and plan perinatal health improvements. 38 39 In the recently completed Ekjut cRCT in rural Jharkhand and Orissa, India, women’s groups met monthly with support from a local facilitator and worked through a participatory learning and action cycle adapted from previously successful work in Nepal. 38 The women identified and prioritised maternal and newborn problems with the help of games, role-play and storytelling, planned strategies to address them with the aid of community meetings, and then put their strategies into practice and adapted them on the basis of experience. For example, some women’s groups prioritised neonatal hypothermia as a local problem. They acquired or made safe delivery kits that included clean cord-cutting equipment and a blanket to wrap the baby in, and distributed them to pregnant women with reminders to use them at the time of delivery. Neonatal mortality was reduced by 45% in the last 2 years of the study (OR 0.45, 95% CI 0.46 to 0.66). 39 A third cRCT of a similar women’s group intervention at lower population coverage found no impact on perinatal outcomes, suggesting that coverage and content are important aspects of this sort of programme. 40 Much of the evidence on the efficacy of social interventions comes from South Asia, and there is less evidence from sub-Saharan Africa. 28 This is changing, as witnessed by recent attention. 41 42 The next few years will see results from cRCTs of home visits by volunteers, extension workers or village health workers in Ethiopia (Community Based Interventions for Newborns (COMBINE): http://www.jsi.com/JSIInternet/Projects/ListProjects.cfm?Select=Country&ID=108), Ghana (Newborn Home Interventions Trial (NEWHINTS)), 43 Tanzania (Improving Newborn Survival in Southern Tanzania (INSIST): http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01022788) and Uganda (Uganda Newborn Survival Study (UNEST): http://www.controlled-trials.com/ISRCTN50321130/UNEST), and a cRCT of community mobilisation through women’s groups in Malawi (MaiMwana). 44

Systems interventions to tackle determinants of health-care, such as finances, require state involvement. User fees are a key impediment to service uptake and their removal is a pro-poor action. Conditional cash transfers are being considered across a number of sectors, and maternity-related payments to mothers and health workers have been introduced recently in Ghana, India and Nepal, where they are primarily aimed at reducing the financial barriers to antenatal and delivery care. 45 An evaluation of Ghana’s free delivery care programme showed increases in service utilisation, but its impact on perinatal mortality has not yet been reported. 46 Recent evidence from India suggests that its maternity incentive scheme is increasing institutional deliveries, and that payment was associated with a reduction of around four perinatal deaths per 1000 pregnancies. 47

THE CURRENT CONSENSUS

Although efforts to implement community-based interventions should not divert policy attention from much needed health system improvements, we have recently moved away from a polarised debate and towards agreement that PMR reduction requires a combination of both. There is an emerging consensus that community-based interventions work, and reasonable clarity on what the health actions contained in packages should be. Amid calls for a continuum of care for women and children and an integrated approach to community health, 9 48 49 the largest shortfall is in evidence to guide policy on the implementation of programmes. 50 51 We know what needs to be done, but not how to do it. We need to make sure that women and their families receive the effective health actions summarised in table 2, with particular coverage of poorer groups served by weaker health services in remoter areas.

QUESTIONS FOR THE JURY

Integrated healthcare

It has often been said that health initiatives work in silos, and that there is a tension between vertical and integrated programming. We wonder if this reflects chronology rather than dysfunction. In the same way that efficacy trials are necessary to test individual actions, it may be that the natural tendency is to begin with a vertical focus on a specific health initiative, and through it to understand the best interventional approaches. Once this understanding is achieved, the intuitive next step is to integrate it with others. This is the point we have reached with, for example, PMTCT of HIV and family planning services. It is also reflected in the recent suggestion that the Global Fund should move beyond AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria to a wider remit. 52

WHO and Unicef now recommend home visits by “appropriately trained and supervised health workers” in the first days of life, 53 and there is reasonable consensus that this should be combined with community mobilisation activities. With proof of principle, how can this approach be taken to scale and still remain effective? 35 Operational research is underway in Africa and Asia, but questions remain about whether over-stretched community health workers can manage the added responsibilities, whether supervision will suffer at scale and whether coverage will extend equitably into poorer communities whose need is greatest. 54 Likewise, health worker actions for infants must accompany actions for maternal and post-neonatal health, reproductive health, nutrition and early child development.

Multiple factors

In thinking about integration, it is worth pointing out that health initiatives have tended to be exclusive rather than inclusive. For example, traditional birth attendants, present at an estimated 23–40% of the world’s home deliveries, 55 have been largely abandoned as a cadre who could take useful health actions to reduce PMR. 56 57 This abandonment has been at the level of international policy rather than ground reality. Non-government organisations (NGOs) often include them in field programmes and express surprise that their ubiquity and coverage have not been harnessed, and there is some evidence that they might help to reduce perinatal mortality. 55 58 In a rural trial in Pakistan, work with traditional birth attendants – and, perhaps more importantly, their active linkage with government health services – was associated with a 30% reduction in perinatal mortality (OR 0.70, 95% CI 0.59 to 0.82).59 A second example is the success of non-government community health workers in managing neonatal sepsis, one of the actions being administration of intramuscular gentamicin. Scale-up has been hampered by concerns about de-restriction of this clinical action to non-clinical cadres. If the success of community-based initiatives has taught us anything, it is that inclusiveness should be central to any initiative to reduce PMR. Building awareness through community dialogue (and institutional perinatal audit) 60 is an intervention in itself, and success is more likely if diverse actors are brought together.

Is change passing us by while we debate the content of public sector healthcare?

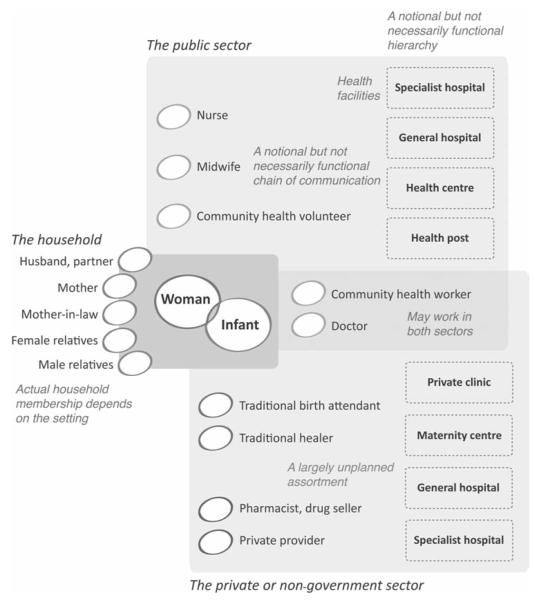

Figure 1 is a schematic presentation of the healthcare options available to a hypothetical woman as she experiences pregnancy in the global South. Her ‘health ecosystem’ includes her family, the public sector, the informal and formal private sector, the non-government sector and the wider community. What ‘should’ happen in an ideal situation is that the woman confirms her pregnancy, attends antenatal care, registers and delivers at an institution and makes a postnatal care visit. The usual view is that all this would take place in the public sector, preferably at a peripheral institution for antenatal and post-natal care, at a basic emergency obstetric care institution for delivery (unless there are predicted risks), and at a comprehensive emergency obstetric care institution for high-risk deliveries and for in-transfer of complicated maternities. What people think actually happens in low-income settings is that the pregnant woman receives advice and support from her close family, delivers her baby aided by a traditional birth attendant or a family member, and has no formal postpartum care. In many low-resource settings, however, there are alternative pathways outside these care-seeking narratives. For example, a woman may have some antenatal care from a local private practitioner, deliver at home with assistance from a local private practitioner, and call in a traditional healer or private practitioner if complications arise. Equally, she may have antenatal care, delivery and postnatal care at private sector institutions, perhaps choosing to deliver in the public sector because delivery is the most expensive stage of the process.

Figure 1.

Potential sources of assistance and healthcare for mothers and newborn infants in a low-income setting.

These emerging scenarios raise concerns and opportunities. First, the role of private providers is growing apace. While the bulk of rural healthcare is provided by government, private providers are found in even the poorest areas. They include traditional birth attendants and healers, public sector health workers supplementing their practice, and informally qualified practitioners. Eighty per cent of India’s outpatient health-care for young mothers is in the private sector. 61 The third sector also has a role in many settings: NGOs such as BRAC are providing over 90 million Bangladeshis with parallel health services (http://www.brac.net). New systems-based interventions should therefore take into account the increasing role of the private sector and NGOs. The private sector’s growing importance means that in many countries government maternity care is now a second-class option, which is precisely why it needs to be strengthened: the risk pool is being segmented so that public services are providing for poorer women at higher risk and threaten to become nexuses of higher perinatal mortality.

The need to strengthen access to quality public health services is strong, and many governments are rising to the challenge by innovating in service delivery and adapting to local circumstances. In India, the government of Orissa has not only successfully increased the institutional delivery rate through an incentive scheme, but also gives women attending antenatal care in underserved areas clean delivery kits for home births. In West Bengal, the government has enlisted the support of self-help groups to mobilise communities for safe practices and care-seeking. Understanding the realities of women’s aspirations and options for care, including the role of community support, private and third sector practitioners, is key to designing the new systems-based interventions needed to improve perinatal outcomes.

CONCLUSION

We have an understanding of the single health actions and packages that will reduce perinatal mortality in low-resource settings. The task is to crystallise a manageable remit for community workers to deliver them, and a clear framework that includes both community-based and institutional care. In order to do this we will need to simplify and integrate, so that human resources, communications, supplies, transport and referral systems fit together. Understanding how to do this will require contributions from the emerging discipline of implementation science. To achieve this we will need methodological innovations that move beyond the probability designs favoured in efficacy research (eg, RCTs) towards the plausibility and adequacy designs (before–after studies, phased roll-out) more suited to large-scale effectiveness evaluations. 62 We also need to acknowledge, attempt to integrate and bench-mark, sources of care outside the public sector. A broadening of focus is needed, rather than a move away from public sector provision, which could be strengthened through partnerships with non-government providers.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Towards 4+5 consortium, funded by the UK Department for International Development, and the Wellcome Trust Strategic Group on the Population Science of Maternal and Child Survival, whose members continue to debate the issues that inform the article.

Footnotes

Funding DO is supported by The Wellcome Trust (081052/Z/06/Z).

Competing interests None.

Provenance and peer review Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lawn J, Kerber K, Enweronu-Laryea C, et al. Newborn survival in low resource settings – are we delivering? BJOG. 2009;116(Suppl 1):S49–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lawn JE, Cousens S, Zupan J. Lancet Neonatal Survival Steering Team. 4 million neonatal deaths:when? Where? Why? Lancet. 2005;365:891–900. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, et al. Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, 2001:systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet. 2006;367:1747–57. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68770-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fikree FF, Azam SI, Berendes HW. Time to focus child survival programmes on the newborn:assessment of levels and causes of infant mortality in rural Pakistan. Bull World Health Organ. 2002;80:271–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO . Neonatal and Perinatal Mortality:Country, Regional and Global Estimates. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lawn JE, Yakoob MY, Haws RA, et al. 3.2 million stillbirths:epidemiology and overview of the evidence review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2009;9(Suppl 1):S2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-9-S1-S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lawn JE, Wilczynska-Ketende K, Cousens SN. Estimating the causes of 4 million neonatal deaths in the year 2000. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35:706–18. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Darmstadt GL, Lee AC, Cousens S, et al. 60 Million non-facility births:who can deliver in community settings to reduce intrapartum-related deaths? Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2009;107(Suppl 1):S89–112. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kerber KJ, de Graft-Johnson JE, Bhutta ZA, et al. Continuum of care for maternal, newborn, and child health:from slogan to service delivery. Lancet. 2007;370:1358–69. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61578-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lawn J, Lee A, Kinney M, et al. Two million intrapartum-related stillbirths and deaths:where, why, and what can be done? Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2009;107:S5–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campbell OM, Graham WJ, Lancet Maternal Survival Series steering group Strategies for reducing maternal mortality:getting on with what works. Lancet. 2006;368:1284–99. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69381-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lawn JE, Kinney M, Lee AC, et al. Reducing intrapartum-related deaths and disability:can the health system deliver? Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2009;107(Suppl 1):S123–40. S140–2. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Darmstadt GL, Bhutta ZA, Cousens S, et al. Lancet Neonatal Survival Steering Team Evidence-based, cost-effective interventions:how many newborn babies can we save? Lancet. 2005;365:977–88. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71088-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhutta ZA, Darmstadt GL, Hasan BS, et al. Community-based interventions for improving perinatal and neonatal health outcomes in developing countries:a review of the evidence. Pediatrics. 2005;115:519–617. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yakoob MY, Menezes EV, Soomro T, et al. Reducing stillbirths:behavioural and nutritional interventions before and during pregnancy. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2009;9(Suppl 1):S3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-9-S1-S3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhutta ZA, Ali S, Cousens S, et al. Alma-Ata:Rebirth and Revision 6 Interventions to address maternal, newborn, and child survival:what difference can integrated primary health care strategies make? Lancet. 2008;372:972–89. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61407-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barros FC, Bhutta ZA, Batra M, et al. GAPPS Review Group Global report on preterm birth and stillbirth (3 of 7):evidence for effectiveness of interventions. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2010;10(Suppl 1):S3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-10-S1-S3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lavender T, Hart A, Smyth RMD. Effect of partogram use on outcomes for women in spontaneous labour at term. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;4:CD005461. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005461.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hofmeyr GJ, Haws RA, Bergström S, et al. Obstetric care in low-resource settings:what, who, and how to overcome challenges to scale up? Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2009;107(Suppl 1):S21–44. S44–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smaill FM, Vazquez JC. Antibiotics for asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;2:CD000490. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000490.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Menezes EV, Yakoob MY, Soomro T, et al. Reducing stillbirths:prevention and management of medical disorders and infections during pregnancy. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2010;9(Suppl 1):S4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-9-S1-S4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haider BA, Bhutta ZA. Multiple-micronutrient supplementation for women during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;4:CD004905. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004905.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahomed K, Bhutta Z, Middleton P. Zinc supplementation for improving pregnancy and infant outcome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;2:CD000230. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000230.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hess SY, King JC. Effects of maternal zinc supplementation on pregnancy and lactation outcomes. Food Nutr Bull. 2009;30:S60–78. doi: 10.1177/15648265090301S105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ronsmans C, Fisher DJ, Osmond C, et al. Maternal Micronutrient Supplementation Study Group Multiple micronutrient supplementation during pregnancy in low-income countries:a meta-analysis of effects on stillbirths and on early and late neonatal mortality. Food Nutr Bull. 2009;30:S547–55. doi: 10.1177/15648265090304S409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Darmstadt GL, Walker N, Lawn JE, et al. Saving newborn lives in Asia and Africa:cost and impact of phased scale-up of interventions within the continuum of care. Health Policy Plan. 2008;23:101–17. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czn001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Family Health Division . National Essential Maternal and Neonatal Health Care Package. Department of Health Services, Ministry of Health, Government of Nepal; Kathmandu: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haws RA, Thomas AL, Bhutta ZA, et al. Impact of packaged interventions on neonatal health:a review of the evidence. Health Policy Plan. 2007;22:193–215. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czm009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koblinsky M, Matthews Z, Hussein J, et al. Lancet Maternal Survival Series steering group Going to scale with professional skilled care. Lancet. 2006;368:1377–86. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69382-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Knippenberg R, Lawn JE, Darmstadt GL, et al. Lancet Neonatal Survival Steering Team Systematic scaling up of neonatal care in countries. Lancet. 2005;365:1087–98. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71145-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carlo WA, Goudar SS, Jehan I, et al. First Breath Study Group Newborn-care training and perinatal mortality in developing countries. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:614–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0806033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bang AT, Bang RA, Baitule SB, et al. Effect of home-based neonatal care and management of sepsis on neonatal mortality:field trial in rural India. Lancet. 1999;354:1955–61. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)03046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kumar V, Mohanty S, Kumar A, et al. Saksham Study Group Effect of community-based behaviour change management on neonatal mortality in Shivgarh, Uttar Pradesh, India:a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372:1151–62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61483-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baqui AH, El-Arifeen S, Darmstadt GL, et al. Projahnmo Study Group Effect of community-based newborn-care intervention package implemented through two service-delivery strategies in Sylhet district, Bangladesh:a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;371:1936–44. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60835-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baqui A, Williams EK, Rosecrans AM, et al. Impact of an integrated nutrition and health programme on neonatal mortality in rural northern India. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:796–804. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.042226. A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bhutta ZA, Memon ZA, Soofi S, et al. Implementing community-based perinatal care:results from a pilot study in rural Pakistan. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:452–9. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.045849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bang AT, Bang RA, Reddy HM. Home-based neonatal care:summary and applications of the field trial in rural Gadchiroli, India (1993 to 2003) J Perinatol. 2005;25(Suppl 1):S108–22. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Manandhar DS, Osrin D, Shrestha BP, et al. Members of the MIRA Makwanpur trial team Effect of a participatory intervention with women’s groups on birth outcomes in Nepal:cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:970–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17021-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tripathy P, Nair N, Barnett S, et al. Effect of a participatory intervention with women’s groups on birth outcomes and maternal depression in Jharkhand and Orissa, India:a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;375:1182–92. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62042-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Azad K, Barnett S, Banerjee B, et al. Effect of scaling up women’s groups on birth outcomes in three rural districts in Bangladesh:a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;375:1193–202. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60142-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kinney MV, Kerber KJ, Black RE, et al. Science in Action:Saving the lives of Africa’s Mothers, Newborns, and Children working group Sub-Saharan Africa’s mothers, newborns, and children:where and why do they die? PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000294. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Friberg IK, Kinney MV, Lawn JE, et al. Science in Action:Saving the lives of Africa’s Mothers, Newborns, and Children working group Sub-Saharan Africa’s mothers, newborns, and children:how many lives could be saved with targeted health interventions? PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000295. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kirkwood BR, Manu A, Tawiah-Agyemang C, et al. NEWHINTS cluster randomised trial to evaluate the impact on neonatal mortality in rural Ghana of routine home visits to provide a package of essential newborn care interventions in the third trimester of pregnancy and the first week of life:trial protocol. Trials. 2010;11:58. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-11-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rosato M, Mwansambo CW, Kazembe PN, et al. Women’s groups’ perceptions of maternal health issues in rural Malawi. Lancet. 2006;368:1180–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69475-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Borghi J, Ensor T, Somanathan A, et al. Lancet Maternal Survival Series steering group Mobilising financial resources for maternal health. Lancet. 2006;368:1457–65. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69383-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Witter S, Adjei S, Armar-Klemesu M, et al. Providing free maternal health care:ten lessons from an evaluation of the national delivery exemption policy in Ghana. Glob Health Action. 2009;2 doi: 10.3402/gha.v2i0.1881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lim SS, Dandona L, Hoisington JA, et al. India’s Janani Suraksha Yojana, a conditional cash transfer programme to increase births in health facilities:an impact evaluation. Lancet. 2010;375:2009–23. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60744-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Martines J, Paul VK, Bhutta ZA, et al. Lancet Neonatal Survival Steering Team Neonatal survival:a call for action. Lancet. 2005;365:1189–97. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71882-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.WHO . Policy Brief One. Integrating Maternal, Newborn and Child Health. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Costello A, Filippi V, Kubba T, et al. Research challenges to improve maternal and child survival. Lancet. 2007;369:1240–3. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60574-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Peterson S. Assessing the scale-up of child survival interventions. Lancet. 2010;375:530–1. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62193-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.The Lancet. The Global Fund:replenishment and redefinition in 2010. Lancet. 2010;375:865. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60366-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.WHO. UNICEF . WHO/UNICEF Joint Statement:Home Visits for the Newborn Child:A Strategy to Improve Survival. WHO/FCH/CAH/09.02. World Health Organization and United Nations Children’s Fund; Geneva and New York: 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nair N, Tripathy P, Prost A, et al. Improving newborn survival in low-income countries:community-based approaches and lessons from South Asia. PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000246. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sibley LM, Sipe TA, Brown CM, et al. Traditional birth attendant training for improving health behaviours and pregnancy outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;3:CD005460. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005460.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.WHO . Beyond the Numbers. Reviewing Maternal Deaths and Complications to Make Pregnancy Safer. Department of Reproductive Health and Research, World Health Organization; Geneva: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Maine D. Safe Motherhood Programs:Options and Issues. Center for Population and Family Health, Columbia University; New York: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sibley LM, Sipe TA. Transition to skilled birth attendance:is there a future role for trained traditional birth attendants? J Health Popul Nutr. 2006;24:472–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jokhio AH, Winter HR, Cheng KK. An intervention involving traditional birth attendants and perinatal and maternal mortality in Pakistan. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2091–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa042830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pattinson R, Kerber K, Waiswa P, et al. Perinatal mortality audit:counting, accountability, and overcoming challenges in scaling up in low- and middle-income countries. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2009;107(Suppl 1):S113–21. S121–2. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bhatia JC, Cleland J. Health-care seeking and expenditure by young Indian mothers in the public and private sectors. Health Policy Plan. 2001;16:55–61. doi: 10.1093/heapol/16.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Victora CG, Habicht JP, Bryce J. Evidence-based public health:moving beyond randomized trials. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:400–5. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.3.400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.WHO . Instruction Manual. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2004. ICD-10. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems:Tenth Revision. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jones G, Steketee RW, Black RE, et al. Bellagio Child Survival Study Group How many child deaths can we prevent this year? Lancet. 2003;362:65–71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13811-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Demicheli V, Barale A, Rivetti A. Vaccines for women to prevent neonatal tetanus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;4:CD002959. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002959.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hofmeyr GJ, Hannah ME. Planned caesarean section for term breech delivery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;3:CD000166. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kenyon S, Boulvain M, Neilson JP. Antibiotics for Preterm Rupture of Membranes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;2:CD001058. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Roberts D, Dalziel SR. Antenatal corticosteroids for accelerating fetal lung maturation for women at risk of preterm birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;3:CD004454. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004454.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Singhal N, Bhutta ZA. Newborn resuscitation in resource-limited settings. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2008;13:432–9. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Saugstad OD, Ramji S, Soll RF, et al. Resuscitation of newborn infants with 21% or 100% oxygen:an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Neonatology. 2008;94:176–82. doi: 10.1159/000143397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wall SN, Lee AC, Niermeyer S, et al. Neonatal resuscitation in low-resource settings:what, who, and how to overcome challenges to scale up? Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2009;107(Suppl 1):S47–62. S63–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Moore ER, Anderson GC, Bergman N. Early skin-to-skin contact for mothers and their healthy newborn infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;3:CD003519. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003519.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bhutta ZA, Zaidi AK, Thaver D, et al. Management of newborn infections in primary care settings:a review of the evidence and implications for policy? Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28:S22–30. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31819588ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bahl R, Martines J, Ali N, et al. Research priorities to reduce global mortality from newborn infections by 2015. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28:S43–8. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31819588d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lumley J, Chamberlain C, Dowswell T, et al. Interventions for promoting smoking cessation during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;3:CD001055. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001055.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lumley J, Watson L, Watson M, et al. Periconceptional supplementation with folate and/or multivitamins for preventing neural tube defects. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;3:CD001056. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Peña-Rosas JP, Fernando E Viteri. Effects and safety of preventive oral iron or iron+folic acid supplementation for women during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;4:CD004736. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004736.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Carroli G, Rooney C, Villar J. WHO programme to map the best reproductive health practices:how effective is antenatal care in preventing maternal mortality and serious morbidity? Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2001;15(Suppl 1):1–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.2001.0150s1001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Victora CG, Rubens CE, the GAPPS Review Group Global report on preterm birth and stillbirth (4 of 7):delivery of interventions. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2010;10(Suppl 1):54. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-10-S1-S4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gamble CL, Ekwaru JP, ter Kuile FO. Insecticide-treated nets for preventing malaria in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;2:CD003755. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003755.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Garner P, Gulmezoglu AM. Drugs for preventing malaria in pregnant women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;4:CD000169. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000169.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Puckett RM, Offringa M. Prophylactic vitamin K for vitamin K deficiency bleeding in neonates. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;4:CD002776. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Riggs MA, Klebanoff MA. Treatment of vaginal infections to prevent preterm birth:a meta-analysis. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2004;47:796–807. doi: 10.1097/01.grf.0000141450.61310.81. discussion 881–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Okun N, Gronau KA, Hannah ME. Antibiotics for bacterial vaginosis or Trichomonas vaginalis in pregnancy:a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:857–68. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000157108.32059.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gulmezoglu AM, Crowther CA, Middleton P. Induction of labour for improving birth outcomes for women at or beyond term. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;4:CD004945. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004945.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Grivell RM, Alfirevic Z, Gyte GM, et al. Antenatal cardiotocography for fetal assessment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;1:CD007863. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007863.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Alfirevic Z, Devane D, Gyte GM. Continuous cardiotocography (CTG) as a form of electronic fetal monitoring (EFM) for fetal assessment during labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;3:CD006066. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.McDonald SJ, Middleton P. Effect of timing of umbilical cord clamping of term infants on maternal and neonatal outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;2:CD004074. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004074.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rabe H, Reynolds G, Diaz-Rossello J. A systematic review and meta-analysis of a brief delay in clamping the umbilical cord of preterm infants. Neonatology. 2008;93:138–44. doi: 10.1159/000108764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Soll RF, Edwards WH. Emollient ointment for preventing infection in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;2:CD001150. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mullany LC, Darmstadt GL, Khatry SK, et al. Topical applications of chlorhexidine to the umbilical cord for prevention of omphalitis and neonatal mortality in southern Nepal:a community-based, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet. 2006;367:910–18. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68381-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tielsch JM, Darmstadt GL, Mullany LC, et al. Impact of newborn skin-cleansing with chlorhexidine on neonatal mortality in southern Nepal:a community-based, cluster-randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e330–40. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Conde-Agudelo A, Belizan JM. Kangaroo mother care to reduce morbidity and mortality in low birthweight infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;2:CD002771. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Jacobs SE, Hunt R, Tarnow-Mordi WO, et al. ooling for newborns with hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;4:CD003311. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003311.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Edwards AD, Brocklehurst P, Gunn AJ, et al. Neurological outcomes at 18 months of age after moderate hypothermia for perinatal hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy:synthesis and meta-analysis of trial data. BMJ. 2010;340:c363. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kramer MS, Kakuma R. Energy and protein intake in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;4:CD000032. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Reveiz L, Gyte GML, Cuervo LG. Treatments for iron-deficiency anaemia in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;2:CD003094. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003094.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Thinkhamrop J, Hofmeyr GL, Adetoro O, et al. Prophylactic antibiotic administration in pregnancy to prevent infectious morbidity and mortality. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;4:CD002250. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Flenady V, King JF. Antibiotics for prelabour rupture of membranes at or near term. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;3:CD001807. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.King JF, Flenady V, Murray L. Prophylactic antibiotics for inhibiting preterm labour with intact membranes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;3:CD001807. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ohlsson A, Shah VS. Intrapartum antibiotics for known maternal Group B streptococcal colonization. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;3:CD007467. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007467.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Bullough C, Meda N, Makowiecka K, et al. Current strategies for the reduction of maternal mortality. BJOG. 2005;112:1180–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Adegoke AA, van den Broek N. Skilled birth attendance-lessons learnt. BJOG. 2009;116(Suppl 1):33–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Dutta AK. Home-based newborn care how effective and feasible. Indian Pediatr. 2009;46:835–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Lee AC, Lawn JE, Cousens S, et al. Linking families and facilities for care at birth:what works to avert intrapartum-related deaths? Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2009;107(Suppl 1):S65–85. S86–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Pattinson RC, Say L, Makin JD, et al. Critical incident audit and feedback to improve perinatal and maternal mortality and morbidity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;4:CD002961. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002961.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Lagarde M, Palmer N. The impact of user fees on health service utilization in low- and middle-income countries:how strong is the evidence? Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:839–48. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.049197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Lawn JE, Osrin D, Adler A, et al. Four million neonatal deaths:counting and attribution of cause of death. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2008;22:410–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2008.00960.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Frøen JF, Gordijn SJ, Abdel-Aleem H, et al. Making stillbirths count, making numbers talk - issues in data collection for stillbirths. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2009;9:58. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-9-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.WHO . Maternity Waiting Homes:A Review of Experiences. World Health Organization; Geneva: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lagarde M, Haines A, Palmer N. Conditional cash transfers for improving uptake of health interventions in low- and middle-income countries:a systematic review. JAMA. 2007;298:1900–10. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.16.1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]