Abstract

Sodium nitroprusside (SNP) is used clinically as a rapid-acting vasodilator and in experimental models as donor of nitric oxide (NO). High concentrations of NO have been reported to induce cardiotoxic effects including apoptosis by the formation of reactive oxygen species. We have therefore investigated effects of SNP on the myofibrillar cytoskeleton, contractility and cell death in long-term cultured adult rat cardiomyocytes at different time points after treatment. Our results show, that SNP treatment at first results in a gradual increase of cytoskeleton degradation marked by the loss of actin labeling and fragmentation of sarcomeric structure, followed by the appearance of TUNEL-positive nuclei. Already lower doses of SNP decreased contractility of cardiomyocytes paced at 2 Hz without changes of intracellular calcium concentration. Ultrastructural analysis of the cultured cells demonstrated mitochondrial changes and disintegration of sarcomeric alignment. These adverse effects of SNP in cardiomyocytes were reminiscent of anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity, which also involves a dysregulation of NO with the consequence of myofibrillar degradation and ultimately cell death. An inhibition of the pathways leading to the generation of reactive NO products, or their neutralization, may be of significant therapeutic benefit for both SNP and anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity.

Key words: cardiomyocytes, anthracyclines, nitric oxide, apoptosis, reactive oxygen species

Introduction

Sodium nitroprusside (SNP) is used clinically as a rapid-acting vasodilator, active on both arteries and veins. Its hypotensive action is accompanied by an unchanged or augmented cardiac output.1 SNP acts by the formation of nitric oxide (NO) and subsequent stimulation of cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP), which in turn leads to a negative inotropic effect and relaxation in muscle cells.2,3 The main toxicity observed clinically with SNP is the gradual release of cyanide, which complexes with the iron of mitochondrial cytochromes and this inhibits ATP production in cells.1,2 Cardiotoxic mechanisms of higher doses of SNP have been investigated in embryonic chick cardiomyocytes, and it was suggest that H2O2 is involved in the pathogenesis of SNP-induced cardiomyocyte cell death.4 SNP-induced apoptosis could be inhibited with antioxidants in the same model system, indicating an important role of reactive oxygen species (ROS).5 The cardiotoxicity of SNP in cardiomyocytes shows similarities to another well-described class of drugs: the anthracycline cancer therapies. Anthracyclines can cause early cardiomyopathy as well as late-onset ventricular dysfunction.6 While apoptosis7 and calcium store depletion8 in cardiomyocytes have been documented mostly at supraclinical doses of anthracyclines, induction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and myofibrillar damage were reported already at subclinical doses.9–12

A direct link between the cardiotoxicity of anthracyclines and effects of NO in the heart has been provided by research on nitric oxide synthases (NOS). Three NOS isoforms are known: neuronal (nNOS, or NOS1), inducible (iNOS, or NOS2), and endothelial (eNOS, or NOS3). The anthracycline doxorubicin (Doxo) binds to all 3 NOS isoforms, leading to inhibition of NOS activity and reduction of the anthracycline.13 Of the three NOS isoforms, NOS3 has the highest affinity for Doxo.13 The deleterious role of NOS3 after the administration of Doxo has been observed previously in vitro and it was shown that the NOS3 reduces doxorubicin to the semiquinone radical. As a consequence, superoxide formation is enhanced and nitric oxide production is decreased.14–16 However, NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME), an inhibitor of the oxygenase domain of NOS3, has been shown to increase mortality after Doxo treatment in mice,17 suggesting that NO synthesis is protective against Doxo-induced cardiac toxicity. Additionally, it has been shown that NOS3-deficient mice had reduced, and NOS3-overexpressors had increased cardiac dysfunction and myocardial injury after Doxo treatment.18 A similar dual action of NO has been demonstrated in cultured embryonic cardiomyocytes:19 whilst low concentrations of NO have protective effects against cell death,9 excessive NO concentrations, particularly in situations when peroxynitrite and H2O2 is formed, might immediately lead to oxidative injury.20 Another field of study where NOS and NO play an important role is hypoxia/reoxygenation, which represents a very common situation in clinical practice. It has been recently demonstrated, that not only short-term hypoxia, but also the subsequent reoxygenation period upregulate the cardiac NO/NOS system until at least 5 days after the hypoxic stimulus.21

Here we demonstrate adverse effects of SNP and their sequence of appearance in long-term cultured adult rat ventricular cardiomyocytes (ARVM) regarding contractility, cytoskeleton degradation, ultrastructural changes of mitochondria, and apoptosis.

Materials and Methods

Isolation of adult rat ventricular cardiomyocytes

Adult (250–300 g) male Wistar rats from an in-house breeding facility were killed by pentobarbital (Streuli Pharma AG, Uznach, Switzerland) injection. Isolation of calcium-tolerant cardiomyocytes was achieved according to previously published methods.22 Cardiomyocytes used for the contractility measurements kept their rod-shaped morphology within 18 h in ACCT medium containing: fatty, acid-free bovine serum albumin 2 mg/mL, L carnitine 2 mM, creatine 5 mM, taurine 5 mM, triiodothyronine 10 nM (all from Sigma, Buchs, Switzerland), penicillin 100 U/mL, and streptomycin 100 mg/mL (Invitrogen, LuBioScience, Lucerne, Switzerland) in MEM199 (Amimed, BioConcept, Allschwil, Switzerland). Cardiomyocytes assumed a star-shaped morphology (long-term model) in medium containing: 20% fetal calf serum (FCS) (PAA laboratories, Austria), cytosine 1-β-D-arabinofuranoside 10 µM, creatine monohydrate (Sigma) 20 mM, penicillin 100 U/mL and streptomycin 100 mg/mL (Invitrogen) in MEM199 (Amimed). All experiments were carried out according to the Swiss animal protection law and with the permission of the state veterinary office. The investigation conforms with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 85–23, revised 1996).

Pharmacological treatments

Doxorubicin hydrochloride (Doxo) (cat. num. D1515), the all-NOS inhibitor L-NG-monomethyl Arginine acetate (L-NMMA) (cat. num. M7033) and sodium nitroprusside dihydrate (SNP) (cat. num. S0501) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Buchs, Switzerland). Ventricular adult rat cardiomyocytes were cultured for 12 days and then treated in the dark with SNP or with Doxo solved in water. The irreversible pan-caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK was obtained from Calbiochem (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and solved in DMSO.

Immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy

Cultures were washed 3 times with PBS, fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde for 15 min, permeablized with 0.2% triton-X in PBS for 10 min, incubated for 30 min with bovine serum albumin (Sigma) 1 mg/mL in PBS at room temperature, incubated over night with the primary antibodies at 4°C, washed 3 times with PBS and incubated 1 h with the secondary antibody. Anti mouse monoclonal antibodies used were for alpha-actinin (Sigma, clone EA-53), and myomesin (clone B-4).23 Anti mouse secondary antibodies were coupled with Alexa Fluor-488 (Invitrogen) and phalloidin coupled with Alexa Fluor-532 (Invitrogen) was used to visualize actin filaments. The morphology of the cytoskeleton was analyzed using an inverted fluorescence microscope LEITZ DM IL (Leica) equipped with a 40× oil objective (Olympus) or with a confocal microscope Zeiss LSM 410 using 64× and 100× oil objectives. Confocal microscopy images are shown as single optical sections.

Electron microscopy

Cardiomyocytes cultured on laminin-coated glass coverslips were fixed for 6 h with 2% glutaraldehyde (Fluka Chemika) in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer at 4°C. Samples were then postfixed for one h in 1% osmium tetroxide, dehydrated stepwise to 70% ethanol and stained en bloc for one h in 2% uranyl acetate in 70% ethanol. Dehydration was carried out by incubation in 90%–100% ethanol and several mixtures of ethanol and propylenoxide (Sigma). After dehydration was completed in 100% propylenoxide, the cells were infiltrated within 24 hours with an epoxy resin based on Epon812 (Epon 20g, DDSA 16 g, NMA 7 g and DMP-30 1 g, all from Fluka Chemika) in a series of ascending mixtures of epoxy resin/propylenoxide. Gelatin capsules filled with 100% resin were placed on the coverslips and the samples were heat polymerized for 48 h at 60°C. The glass coverslips were then removed from the resin by immersion of the capsules in liquid nitrogen. Ultrathin sections of the surface of the block were cut on a Reichert Diatom ultramicrotome, placed on carbon and formvar coated copper grids (Provac, Sprendlingen, Germany) and were poststained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate according to standard procedures. Preparations were examined in a JEOL JEM100C (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) transmission electron microscope at 80 kV.

Contractility and calcium transients

Glass coverslips with attached ARVMs were incubated for 15 min in Tyrode's buffer (in mmol/L: NaCl 137, KCl 5.4, CaCl2 1.2, MgCl2 0.5, HEPES 10, and glucose 10, pH 7.4, 37°C) containing 1 mmol/L of membrane-permeant fura-2-AM (Invitrogen) and rinsed with Tyrode's buffer containing 500 mmol/L of probenecid to prevent leakage of fura-2. Temperature stability in the closed chamber assembly and superfused buffer was continuously monitored and automatically maintained by a temperature controller (Warner Instru - ment Corp., Hamden, CT, USA). Cells were electrically field-stimulated at a frequency of 2 Hz (Myopacer, Ionoptix, Milton, MA, USA). Several contraction events were averaged for transient analysis and all sarcomere length and calcium measurements were equally filtered by a lowpass Butterworth algorithm in IonWizard (IonOptix). Contractile properties and intracellular Ca2+ ratios were analyzed as described.24

Cell death assays

Terminal deoxyribonucleotidyltransferase-mediated d-Uridine 5' triphosphate nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay was performed according to the manufacturers instructions (In situ cell death detection kit AP, Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN, USA), with the exception of prolonged permeabilization and incubation steps. Incubation with DNAse I (Sigma) was used as positive control for DNA nick labeling. DNAse application in untreated cardiomyocytes led to TUNEL-positive nuclei in 100% of cells (not shown). Caspase-3 activity was assessed using the substrate Asp-Glu-Val-Asp coupled to a fluorescent compound (BioVision, Mountain View, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The reduction of 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) in cells is considered an indicator of cellular viability and was shown to be a measure of the rate of glycolytic NADH production by microsomal enzymes.25 Cells were incubated for 2 hours at 37°C in the dark with MTT (Invitrogen) solved in Tyrode's buffer. Cells were then washed and lysed to release formazan (lysis buffer: 0.6% glacial acetic acid and 10% SDS in DMSO) and lysates were analyzed using a Safire Infinite200 multiwell-plate reader (Tecan Group, Männedorf, Switzerland).

Statistical analysis

All values are expressed as mean ±SD. Statistical analysis of differences observed between the groups was performed by Student's unpaired t-test. Statistical significance was accepted at the level of P<0.05. Graph layouts were created with the program Prism 5 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA).

Results

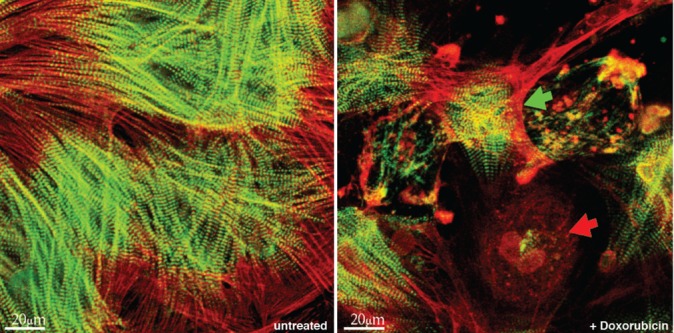

Loss of myofibril integrity in car-diomyocytes treated with Doxo

The anthracycline Doxo leads to degradation of sarcomeric proteins in cardiomyocytes already at sub-apoptotic concentrations.8 Cardiomyocytes were isolated and cultured for 12 days. The cells formed a dense monolayer of spontaneously contracting cells indicating the completed re-formation of myofibrils, which was confirmed by immunostaining for the M-line protein myomesin and actin and confocal microscopy (Figure 1, left). After treatment with Doxo (1 µM for 48 h) the cells showed myofibrillar disarray at variable extent from almost unchanged morphology in some cells to a complete loss of myofibrils in others (Figure 1, right).

Figure 1.

Doxo induces myofibrillar structural damage in ARVM. Cells were cultured for 12 days and then treated with 1 µM of Doxo for 48 h. ARVM were stained for all actin using rhodamin-phalloidin (red) and immunostained for the M-line protein myomesin (green). Left: untreated ARVM. Right: structural damage was heterogeneously distributed in the cultures treated with Doxo including the presence of virtually unchanged cells (green arrow) and others losing all sarcomeric structure (red arrow). Cells from 4 hearts were independently treated and analyzed.

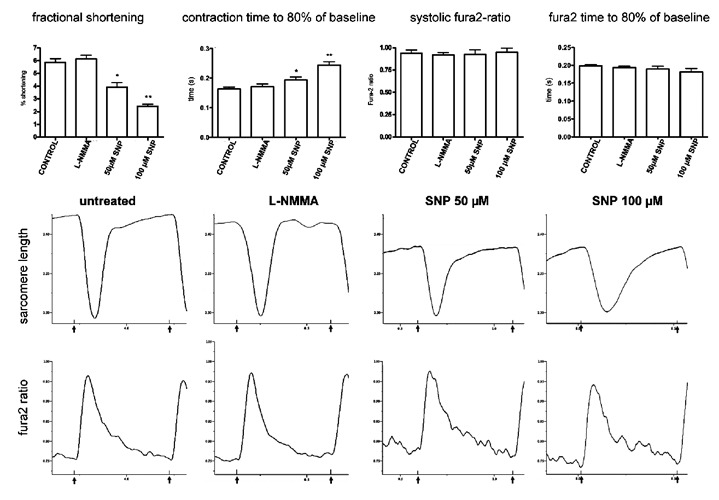

Contractility and intracellular calcium in cardiomyocytes treated with SNP

We were interested to investigate the contractile properties and calcium handling in adult cardiomyocytes treated with SNP not acutely, but at a later time point after treatment that more closely represents sustained injury (18 h) in our experiments (Figure 2). For this purpose, adult rat cardiomyocytes were freshly isolated, kept in serum-free medium on glass coverslips, treated for 18 h as indicated and measured at 37°C and with electrical field pacing at 2 Hz. The all-NOS inhibitor L-NMMA alone did not significantly change fractional shortening nor intracellular calcium (Figure 2). Treatment with SNP at 50 µM and 100 µM resulted in a significant reduction of fractional shortening, of the return time from peak of contraction to 80% of the baseline value, but not of systolic peak calcium. This finding could be partially explained with the known negative inotropic effect of NO via cGMP and reduction of calcium sensitivity of myofibrils3,26,27 or, additionally, with the onset of myofibrillar disarray and further cellular injury after chronic treatment in our experiments.

Figure 2.

Effect of chronic SNP treatment on contractility and calcium. Freshly isolated cardiomyocytes were cultured in serum-free medium and treated with the all-NOS inhibitor L-NMMA 100 µM or sodium nitroprusside as indicated for 18 h before measurement at 37°C and with 2 Hz electrical field pacing. SNP at 50 and 100 µM caused a significant reduction of fractional shortening (left) and of the late phase of relaxation, but no significant change of systolic fura-2 ratio (right) or its kinetics in the late phase of relaxation. L-NMMA did not induce significant changes in any of the measured parameters. Typical contraction and fura2-transients are shown below for each treatment. Black arrows below the time axis indicate the pacing events. *P<0.05 vs untreated, **P<0.001 vs untreated, n = 20 cells from 3 hearts.

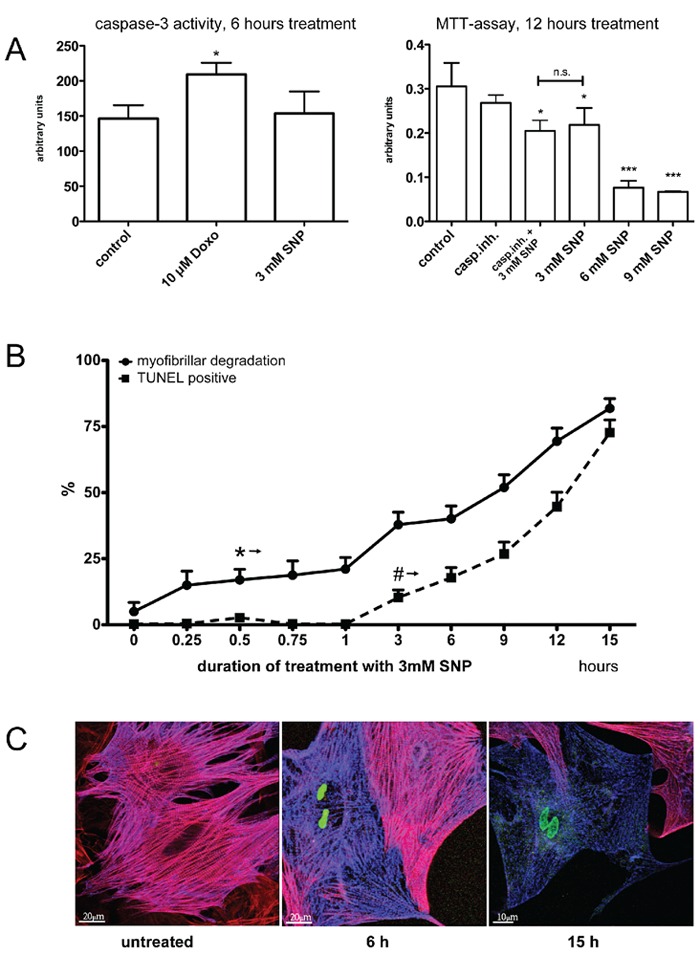

Sequence of the appearance of cells showing myofibrillar degradation and cell death

We have studied the effect of SNP on cell death parameters and cytoskeleton changes at different time points and SNP concentrations (Figure 3). Cardiomyocytes cultured for 12 days were exposed to doxorubicin 10 µM or SNP 3 mM and caspase-3 activity was assessed in cell lysates (Figure 3A, left). The earlier time point of 6 hours was chosen in order to capture the initial stage of cellular damage. Doxorubicin but not SNP led to a significant increase of caspase-3 activity in this experiment. Cell viability after 12 h of treatment with different doses of SNP was then assessed using the MTT-assay (Figure 3 A, right). A significant reduction of formazan formation and viability was found with SNP at 3mM and a strong reduction with 6 and 9 mM respectively. The treatment with a pan-caspase inhibitor (Z-VAD-FMK, 20 µM) did not significantly change viability alone, but failed to rescue the effect of 3 mM SNP. We then assessed DNA degradation and cytoskeleton changes in the same cells (Figure 3B). The cells were fixed and processed with the TUNEL assay after treatment with SNP 3 mM for different times, then immunostained for cytoskeleton proteins alpha-actinin (in blue) and F-actin (in red). It turned out, that the F-actin staining was generally fading away earlier than alpha-actinin in cardiomyocytes with TUNEL-positive nuclei. Structural damage as assessed from confocal images was already statistically significant after 30 min treatment (P<0.05 vs untreated), whereas cells with DNA degradation appeared only after 3 h. Myofibrillar degradation reached P<0.05 compared to untreated cells already after 0.5 h, whereas the percentage of TUNEL positive cells required 3 h to reach the same level of statistical significance.

Figure 3.

Viability and myofibrillar structure. Isolated ARVM were cultured for 14 days then treated with SNP or Doxo and cell viability and structural changes were analyzed. A) Left: assay for caspase-3 activity after treatment with 3 mM SNP or 10 µM Doxo for 6 h. Right: MTT assay after treatment with different concentrations of SNP or a pan-caspase inhibitor for 12 hours. B, C) Cultures were treated with 3 mM SNP for 0–15 h and processed with the TUNEL assay (positive nuclei: green), then immunostained for actin (red) and alpha-actinin (blue) and counted. The * and # signs in (B) indicate the time points, when results became significant vs untreated cells at the level of P<0.05 and better in all following measurements. Representative confocal images as shown in (C), 20 fields in each condition, were used for assessing the percentage of cells displaying morphological changes. * and # P<0.05 vs untreated, ***P<0.001 vs untreated, cells were isolated from 3 hearts and independently processed.

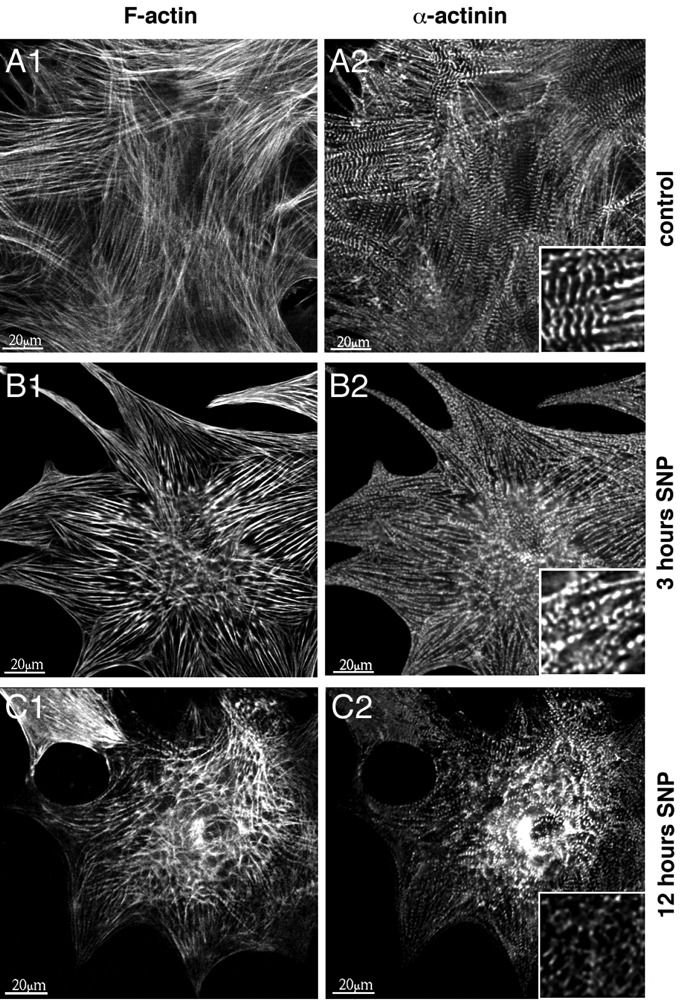

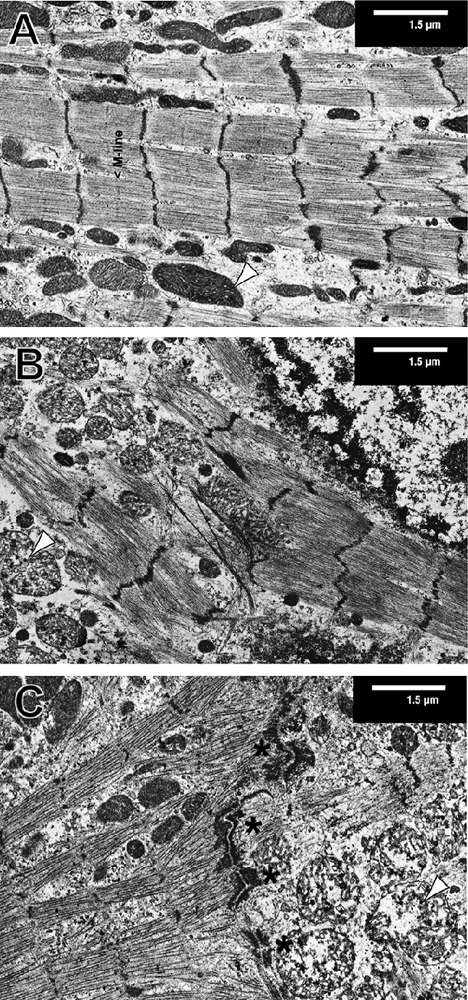

Gradual degradation of the sarcomeric and non-sarcomeric cytoskeleton and mitochondrial changes

Figure 4 shows the gradual degradation of the cytoskeleton of cardiomyocytes treated with 3 mM SNP and fixed and immunostained for alpha-actinin and F-actin. It is possible to clearly discern the sarcomeric cytoskeleton marked by the Z-discs of sarcomeres labeled with alpha-actinin from the non-sarcomeric part showing actin cables and a bead-like structure in the alpha-actinin channel (Figure 4, A1/A2). The insets show the boundary of these two types of cytoskeletal structures. However, after SNP treatment, this separation gets blurred and is replaced by an overall punctate pattern for alpha-actinin and a rarefication and clumping of the actin filaments (Figure 4, B1/B2), a pattern that is even more pronounced after 12 h of SNP-treatment (Figure 4, C1/C2). Additional evidence for the relevance of SNP-induced effects on the cytoskeleton structure was provided by electron microscopy of cultured cardiomyocytes (Figure 5). Untreated cells in long-term culture for 14 days showed well-developed myofibrils and mitochondria (Figure 5A). M-lines were occasionally discernible in sarcomeres. ARVM were then treated with 3 mM SNP for 2 and 5 h (Figure 5 B,C). Myofibril disintegration marked by fragmentation of Z-discs and mitochondrial swelling was observed after 2 h of SNP treatment (Figure 5B). These changes were more pronounced after 5 h treatment. Figure 6C shows a cell-cell contact area (asterisks) with cardiomyocytes on both sides displaying different levels of damage, as judged by the grade of mitochondrial changes and degradation of myofibrils.

Figure 4.

SNP gradually affects myofibrillar integrity over time. Isolated ARVM were cultured for 14 days then treated with 3 mM SNP for 3 and 12 h. Typical cells are shown out of 15 photographed areas for each condition from 3 independently processed hearts. ARVM were stained with rhodamin-phalloidin for all actin (A1–C1) and immunostained for α-actinin (A2–C2). Magnified inserts in the α-actinin column demonstrate the gradual degradation of sarcomeric structure including clumping of myofibrils and contraction of the cells.

Figure 5.

SNP alters the ultra-structure of cardiomyocytes. Isolated ARVM were cultured for 14 days then treated with 3 mM SNP for 0 (A), 3 (B) and 5 (C) hours and processed for electron microscopy. Typical cells are shown out of 15 areas for each condition from 3 independently processed hearts. Mitochondrial swelling was observed in SNP-treated cultures. Typical mitochondria are indicated with black arrowheads (A–C). Fasciae adherens and desmosomes are visible in the middle of image C (black asterisks) indicating a line of cell-cell contacts between two cardiomyocytes differently affected by the SNP treatment.

Discussion

Deterioration of myofibrillar structure in cardiac muscle tissue is a common feature of several types of cardiomyopathies. Such pathological changes in the myocardium are commonly observed in human heart failure of different etiologies28,29 and also in experimental models such as in dogs with low coronary blood flow resulting in the so-called myocardial stunning.30 In clinical cardiotoxicity associated with cancer chemotherapies, morphological changes in the myocardium have been correlated with early cardiac dysfunction,12,31 which usually is reversible and does not pose an immediate concern for the health of the patient.32

The connecting feature of the above mentioned observations is cardiomyocyte injury, although the molecular mechanisms may differ, and there is a general need for therapeutic interventions to rescue the cells before irreversible damage leads to cell death. Adult cardiomyocytes treated with a high dose of SNP displayed myofibrillar degradation proportionally to exposure time. The results of the immunofluorescence experiments were confirmed by electron microscopy demonstrating the gradual disintegration of cytoskeleton fine structure and the considerable heterogeneity of cellular damage in cultures treated with SNP. This cellular injury is probably also the cause of defects in contractility of electrically stimulated cardiomyocytes, although we have to consider that several factors could contribute to this effect after chronic treatment. Apoptosis, as assessed by DNA degradation, was observed after longer exposure, increasing only after a certain threshold of cellular damage. A similar outcome was observed with anthracyclines in cultured adult cardiomyocytes.33 Is the structural damage the effect or the cause of apoptosis? Our results using caspase-3 activity and the TUNEL-assay suggest, that apoptosis may not be involved in the earlier cellular injury by SNP, when the cytoskeleton changes are already visible. However, the formation of ROS usually has multifactorial consequences in cells, often affecting mitochondria, and many of these effects will ultimately lead to necrosis and apoptosis. Both anthracyclines and SNP interfere with mitochondrial metabolism, either by complexation of the iron of several mitochondrial enzymes with cyanide,4 or by modulation of mitochondrial enzymes and interaction with cardiolipin and oxidative stress in the case of anthracyclines (for review10). NO does indeed play a role in anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity, as mentioned in the introduction, by interaction with NOS3 and the formation of superoxide.14–16 So far, it seems that attenuation of anthracycline-induced free radical formation is an efficient strategy to preserve myocardial viability and function.34 The iron chelator dexrazoxane (Zinecard®) has been successfully used to this aim in vitro35 and in clinical practice36 without significantly diminishing antitumor activity of the chemotherapeutic regimen. An inhibition of the pathways leading to the generation of reactive NO products and ROS in general, or their neutralization, may be of significant therapeutic benefit for both SNP and anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity.

Acknowledgements:

the authors thank Enzo Busceti for excellent technical assistance and Dr. Sigrid M. Aigner for valuable discussions on SNP-induced cell death in long-term cultured adult rat ventricular cardiomyocytes.

References

- 1.Verner IR. Sodium nitroprusside: theory and practice. Postgrad Med J. 1974;50:576–81. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.50.587.576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kukovetz WR, Holzmann S, Schmidt K. Cellular mechanisms of action of therapeutic nitric oxide donors. Eur Heart J. 1991;12(Suppl E):16–24. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/12.suppl_e.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mohan P, Brutsaert DL, Paulus WJ, Sys SU. Myocardial contractile response to nitric oxide and cGMP. Circulation. 1996;93:1223–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.6.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rabkin SW, Kong JY. Nitroprusside induces cardiomyocyte death: interaction with hydrogen peroxide. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;279:H3089–100. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.6.H3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pignatti C, Tantini B, Stefanelli C, Giordano E, Bonavita F, Clo C, et al. Nitric oxide mediates either proliferation or cell death in cardiomyocytes. Involvement of polyamines. Amino Acids. 1999;16:181–90. doi: 10.1007/BF01321535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lipshultz SE, Colan SD, Gelber RD, Perez-Atayde AR, Sallan SE, Sanders SP. Late cardiac effects of doxorubicin therapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia in childhood. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:808–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199103213241205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sawyer DB, Fukazawa R, Arstall MA, Kelly RA. Daunorubicin-induced apoptosis in rat cardiac myocytes is inhibited by dexrazoxane. Circ Res. 1999;84:257–65. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.3.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lim CC, Zuppinger C, Guo X, Kuster GM, Helmes M, Eppenberger HM, et al. Anthracyclines induce calpain-dependent titin proteolysis and necrosis in cardiomyocytes. J Biol Chem. 2004 Feb 27;279:8290–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308033200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Timolati F, Ott D, Pentassuglia L, Giraud MN, Perriard JC, Suter TM, et al. Neuregulin-1 beta attenuates doxorubicin-induced alterations of excitation-contraction coupling and reduces oxidative stress in adult rat cardiomyocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006;41:845–54. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tokarska-Schlattner M, Zaugg M, Zuppinger C, Wallimann T, Schlattner U. New insights into doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity: the critical role of cellular energetics. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006;41:389–405. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sawyer DB, Zuppinger C, Miller TA, Eppenberger HM, Suter TM. Modulation of anthracycline-induced myofibrillar disarray in rat ventricular myocytes by neuregulin-1beta and anti-erbB2: potential mechanism for trastuzumab-induced cardiotoxicity. Circulation. 2002;105:1551–4. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000013839.41224.1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Billingham ME, Mason JW, Bristow MR, Daniels JR. Anthracycline cardiomyopathy monitored by morphologic changes. Cancer Treat Rep. 1978;62:865–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garner AP, Paine MJ, Rodriguez-Crespo I, Chinje EC, Ortiz De Montellano P, Stratford IJ, et al. Nitric oxide synthases catalyze the activation of redox cycling and bioreductive anticancer agents. Cancer Res. 1999;59:1929–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vasquez-Vivar J, Martasek P, Hogg N, Masters BS, Pritchard KA, Jr., Kalyanaraman B. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase-dependent superoxide generation from adriamycin. Biochemistry. 1997;36:11293–7. doi: 10.1021/bi971475e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kalivendi SV, Kotamraju S, Zhao H, Joseph J, Kalyanaraman B. Doxorubicin-induced apoptosis is associated with increased transcription of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase. Effect of antiapoptotic antioxidants and calcium. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:47266–76. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106829200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mukhopadhyay P, Rajesh M, Batkai S, Kashiwaya Y, Hasko G, Liaudet L, et al. Role of superoxide, nitric oxide, and peroxynitrite in doxorubicin-induced cell death in vivo and in vitro. American journal of physiology Heart and circulatory physiology. 2009;296:H1466–83. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00795.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pacher P, Liaudet L, Bai P, Mabley JG, Kaminski PM, Virag L, et al. Potent metalloporphyrin peroxynitrite decomposition catalyst protects against the development of doxorubicin-induced cardiac dysfunction. Circulation. 2003;107:896–904. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000048192.52098.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neilan TG, Blake SL, Ichinose F, Raher MJ, Buys ES, Jassal DS, et al. Disruption of nitric oxide synthase 3 protects against the cardiac injury, dysfunction, and mortality induced by doxorubicin. Circulation. 2007;116:506–14. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.652339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heineke J, Kempf T, Kraft T, Hilfiker A, Morawietz H, Scheubel RJ, et al. Downregulation of cytoskeletal muscle LIM protein by nitric oxide: impact on cardiac myocyte hypertrophy. Circulation. 2003;107:1424–32. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000055319.94801.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rabkin SW, Kong JY. Nitroprusside induces cardiomyocyte death: interaction with hydrogen peroxide. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;279:H3089–100. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.6.H3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rus A, Del Moral ML, Molina F, Peinado MA. Upregulation of cardiac NO/NOS system during short-term hypoxia and the subsequent reoxygenation period. Eur J Histochem. 2011;55:e17–e17. doi: 10.4081/ejh.2011.e17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kondo RP, Apstein CS, Eberli FR, Tillotson DL, Suter TM. Increased calcium loading and inotropy without greater cell death in hypoxic rat cardiomyocytes. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:H2272–82. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.6.H2272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grove BK, Kurer V, Lehner C, Doetschman TC, Perriard JC, Eppenberger HM. A new 185,000-dalton skeletal muscle protein detected by monoclonal antibodies. J Cell Biol. 1984;98:518–24. doi: 10.1083/jcb.98.2.518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Timolati F, Ott D, Pentassuglia L, Giraud MN, Perriard JC, Suter TM, et al. Neuregulin-1 beta attenuates doxorubicin-induced alterations of excitation-contraction coupling and reduces oxidative stress in adult rat cardiomyocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006;41:845–54. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berridge MV, Tan AS. Characterization of the cellular reduction of 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT): subcellular localization, substrate dependence, and involvement of mitochondrial electron transport in MTT reduction. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1993;303:474–82. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1993.1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ungureanu-Longrois D, Bezie Y, Perret C, Laurent S. Effects of exogenous and endogenous nitric oxide on the contractile function of cultured chick embryo ventricular myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1997;29:677–87. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1996.0310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yong QC, Hu LF, Wang S, Huang D, Bian JS. Hydrogen sulfide interacts with nitric oxide in the heart: possible involvement of nitroxyl. Cardiovascular research. 2010 Dec 1;88(3):482–91. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kostin S, Pool L, Elsasser A, Hein S, Drexler HC, Arnon E, et al. Myocytes die by multiple mechanisms in failing human hearts. Circ Res. 2003;92:715–24. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000067471.95890.5C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kostin S, Rieger M, Dammer S, Hein S, Richter M, Klovekorn WP, et al. Gap junction remodeling and altered connexin43 expression in the failing human heart. Mol Cell Biochem. 2003;242:135–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Decker RS, Decker ML, Nakamura S, Zhao YS, Hedjbeli S, Harris KR, et al. HSC73-tubulin complex formation during low-flow ischemia in the canine myocardium. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;283:H1322–33. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00062.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shan K, Lincoff AM, Young JB. Anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:47–58. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-1-199607010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bristow MR, Thompson PD, Martin RP, Mason JW, Billingham ME, Harrison DC. Early anthracycline cardiotoxicity. Am J Med. 1978;65:823–32. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(78)90802-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Timolati F, Anliker T, Groppalli V, Perriard JC, Eppenberger HM, Suter TM, et al. The role of cell death and myofibrillar damage in contractile dysfunction of long-term cultured adult cardiomyocytes exposed to doxorubicin. Cytotechnology. 2009;61:25–36. doi: 10.1007/s10616-009-9238-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zuppinger C, Suter TM. Cancer therapy-associated cardiotoxicity and signaling in the myocardium. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2010;56:141–6. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3181e0f89a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen B, Peng X, Pentassuglia L, Lim CC, Sawyer DB. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of anthracycline cardiotoxicity. Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2007;7:114–21. doi: 10.1007/s12012-007-0005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lopez M, Vici P. European trials with dexrazoxane in amelioration of doxorubicin and epirubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Semin Oncol. 1998;25(4) Suppl 10:55–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]