Abstract

Background

The purposes of this study were to investigate the prevalence of psychotropic (hypnotic, antidepressant, and anxiolytic) drug use among adolescents aged 15–16 years during the period 2006–2010 according to gender and subcategories of psychotropics, and to study psychotropic drug use over the period 2007–2010 among incident users in 2007.

Methods

This was a one-year prevalence and follow-up study based on information retrieved from the nationwide Norwegian prescription database for the period 2006–2010. The study population consisted of adolescents aged 15–16 years who had filled at least one prescription for a psychotropic drug in the study period. The main outcome measures were filling of hypnotic, antidepressant, and/or anxiolytic drug prescriptions.

Results

Overall use of psychotropic drugs increased from 13.9 to 21.5 per 1000 among boys and from 19.7 to 24.7 per 1000 among girls during the 2006– 2010 period. Hypnotic drugs, and melatonin in particular, accounted for most of the increase. For melatonin, the annual median amount dispensed was 180 defined daily doses through the period until 2010, at which time it decreased to 90 defined daily doses. In total, 16.4% of all incident psychotropic drug users in 2007 were still having prescriptions dispensed in 2010.

Conclusion

This study shows an increase in hypnotic drugs dispensed for adolescents in Norway, mainly attributable to the increasing use of melatonin. The amount of melatonin dispensed indicates more than sporadic use over longer periods, despite melatonin only being licensed in Norway for use in insomnia for individuals aged 55 years or older.

Keywords: psychotropic drugs, hypnotics, sedatives, antidepressive agents, antianxiety agents, adolescents, prescription database, defined daily dose, long-term use

Introduction

International studies in recent decades have shown an increase in psychotropic drug use among adolescents. In the US, this use has increased by 2–3-fold in the past 20 years.1,2 In Norway, and other Nordic countries, the overall use of psychotropic drugs by adolescents seems to be low, except for Iceland, where it is reported to be high.3,4

In 2005, Skurtveit et al3 found a relatively low self-reported use of psychotropic drugs in a Norwegian urban adolescent population, being about 4% among girls and boys. However, between 2004 and 2009, there was a trend of increasing hypnotic drug use by Norwegian adolescents.5 Furthermore, incident use seemed to be high among those aged 15–16 years in 2000–2003, and 15% had filled at least one prescription for one of the study drugs 1–9 years later.6

The appropriateness of psychotropic drug use among adolescents is controversial. As early as 1994, Simeon et al7 described knowledge about psychotropic drug use in this group as developing slowly because of lack of research, ethical issues, regulations, and opposition to use of psychotropic medication in adolescents. Today, studies claim that too many psychotropic drugs are used off-label in adolescents.8–10

Variations in psychotropic drug use between young populations have been observed in previous studies, which may reflect variations in culture, guidelines, health service organization, economic and diagnostic criteria, and study design.8,10 Several earlier studies exploring psychotropic drug use are based on self-reported information, insurance or reimbursement data, and community or localized pharmacy dispensing data.4,10–12 In this context, the nationwide Norwegian prescription database constitutes a valid data source for conducting pharmacoepidemiological studies at an individual level in an unselected adolescent population.13

Overall, studies on psychotropic drug use among adolescents are scarce and do not give any detailed information on patterns of use over time by age, gender, or subcategory of psychotropic medication. The purposes of this study were to investigate the one-year prevalence of psychotropic ( hypnotic, antidepressant, anxiolytic) drug use among adolescents aged 15–16 years during 2006–2010 related to gender and subcategories of psychotropic medication, and to study use of psychotropic drugs in the period 2007–2010 among incident psychotropic drug users in 2007.

Materials and methods

This study is based on data from the Norwegian prescription database during 2006–2010.13 Since January 1, 2004, all pharmacies in Norway have been legally obliged to send in electronic data on all prescriptions to the Norwegian Institute of Public Health. The Norwegian prescription database contains information on all individuals living outside institutions who have received drug prescriptions dispensed at pharmacies. All prescriptions, whether reimbursed or not, are stored in the database. The drugs are categorized according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification system.13,14 The data collected for this study included patient unique identifying number (encrypted), gender, age, date of dispensing, and drug information (ATC code, defined daily dose).

Quantities of dispensed drugs are measured in terms of the number of defined daily doses. The defined daily dose is the assumed average maintenance dose per day for a drug used among adults for its main indication.14 Psychotropic subcategories in this study included antidepressant, hypnotic, and anxiolytic drugs. Table 1 show all psychotropic substances included in this study with assigned defined daily doses.

Table 1.

Psychotropic substances registered in Norway in 2011, and included in the study with assigned defined daily doses

| ATC code | Name | DDD |

|---|---|---|

| N05C hypnotics and sedatives | ||

| N05CA barbiturates, plain | ||

| N05CA04 | Barbital | 500 mg |

| N05CD benzodiazepine derivatives | ||

| N05CD02 | Nitrazepam | 5 mg |

| N05CD03 | Flunitrazepam | 1 mg |

| N05CD08 | Midazolam | 15 mg |

| N05CF benzodiazepine-related drugs (Z hypnotics) | ||

| N05CF01 | Zopiclone | 7.5 mg |

| N05CF02 | Zolpidem | 10 mg |

| N05CH melatonin receptor agonists | ||

| N05CH01 | Melatonin | 2 mg |

| N05CM other hypnotics and sedatives | ||

| N05CM02 | Clomethiazole | 150 mg |

| N05CM05 | Scopolamine | 0.9 mg |

| R06 antihistamines for systemic use | ||

| R06 AD phenothiazine derivatives | ||

| R06AD01 | Alimemazine | 30 mg |

| R06AD02 | Promethazine | 25 mg |

| N06A antidepressants | ||

| N06 AA nonselective monoamine reuptake inhibitors | ||

| N06AA04 | Clomipramine | 100 mg |

| N06AA06 | Trimipramine | 150 mg |

| N06AA09 | Amitriptyline | 75 mg |

| N06AA10 | Nortriptyline | 30 mg |

| N06AA12 | Doxepin | 100 mg |

| N06 AB selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors | ||

| N06AB03 | Fluoxetine | 120 mg |

| N06AB04 | Citalopram | 20 mg |

| N06AB05 | Paroxetine | 20 mg |

| N06AB06 | Sertraline | 50 mg |

| N06AB08 | Fluvoxamine | 100 mg |

| N06AB10 | Escitalopram | 10 mg |

| N06 AG monoamine oxidase A inhibitor | ||

| N06AG02 | Moclobemide | 300 mg |

| N06 AX other antidepressants | ||

| N06AX03 | Mianserin | 60 mg |

| N06AX11 | Mirtazapine | 30 mg |

| N06AX12 | Bupropion | 300 mg |

| N06AX16 | Venlafaxine | 100 mg |

| N06AX18 | Reboxetine | 8 mg |

| N06AX21 | Duloxetine | 60 mg |

| N05B anxiolytics | ||

| N05BA benzodiazepine derivatives | ||

| N05BA01 | Diazepam | 10 mg |

| N05BA04 | Oksazepam | 50 mg |

| N05BA12 | Alprazolam | 1 mg |

| N05BB diphenylmethane derivatives | ||

| N05BB01 | Hydroxyzine | 75 mg |

| N05BE azaspirodecanedione derivatives | ||

| N05BE01 | Buspirone | 30 mg |

Abbreviations: ATC code, Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification system; DDD, defined daily doses.

Phenothiazine-derivative systemic antihistamines (ATC code R06AD) have long been used for childhood insomnia in Norway, and constituted the second most commonly prescribed hypnotic drug among adolescents aged 0–17 years in Norway in 2008. For this reason, phenothiazine prescriptions were included in the analysis and are referred to as “hypnotic drugs”, together with Z drugs and benzodiazepines (ATC code N05C).

The study population consisted of adolescents aged 15–16 years in 2006, 2008, and 2010, who had filled at least one prescription for any of the psychotropic drug subcategories. The age of 15–16 years constitutes a special time of growth, with many social, mental and physical changes taking place. The Norwegian prescription database covers the entire nation, which renders it possible to study patterns of use in narrow age bands.

Analytical approaches

The one-year prevalence of psychotropic drug use in 2006, 2008, and 2010, overall, and in psychotropic drug subgroups, was estimated by identifying individuals who had at least one prescription filled in that year per 1000 inhabitants. The denominator is based on the total number of Norwegian inhabitants aged 15–16 years in the actual year registered by Statistics Norway.15 The annual amounts of psychotropic drugs used are presented as median and interquartile ranges.

Among incident drug users in 2007, the proportion of continued use throughout the period was calculated. An incident user in 2007 was defined as having at least one prescription filled in 2007 and none during 2004–2006. Long-term use was defined as filling of at least one prescription each year in the period 2007–2010 by a 2007 incident drug user. Analyses were performed using SPSS 17.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL).

Results

One-year prevalence of psychotropic drug use versus subcategory and gender

Overall, one-year prevalence of psychotropic drug use increased among adolescents in the period 2006–2010 from 2130 (16.7 per 1000) in 2006 to 2949 (23.0 per 1000) in 2010. Among the boys, one-year prevalence increased during this period from 13.9 to 21.5 per 1000 inhabitants. Among the girls, the corresponding figures were 19.7 and 24.7 per 1000 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Norwegian prescription database showing one-year prevalence of use of psychotropic drugs by boys and girls aged 15–16 years

| 2006 | 2008 | 2010 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

| Boys (n) 65,481 | Girls (n) 62,090 | Boys (n) 64,928 | Girls (n) 61,354 | Boys (n) 65,956 | Girls (n) 62,056 | |||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| n | /1000 | n | /1000 | n | /1000 | n | /1000 | n | /1000 | n | /1000 | |

| Any psychotropic below | 909 | 13.9 | 1221 | 19.7 | 1151 | 17.7 | 1373 | 22.4 | 1418 | 21.5 | 1531 | 24.7 |

| Hypnotics (ATC code N05C + R06AD) | 612 | 9.3 | 726 | 11.7 | 877 | 13.5 | 942 | 15.4 | 1144 | 17.3 | 1077 | 17.4 |

| Antidepressants (ATC code N06A) | 282 | 4.3 | 487 | 7.8 | 322 | 5.0 | 503 | 8.2 | 344 | 5.2 | 559 | 9.0 |

| Anxiolytics (ATC code N05B) | 152 | 2.3 | 232 | 3.7 | 150 | 2.3 | 225 | 3.7 | 151 | 2.3 | 209 | 3.4 |

Abbreviation: ATC code, The Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification system.

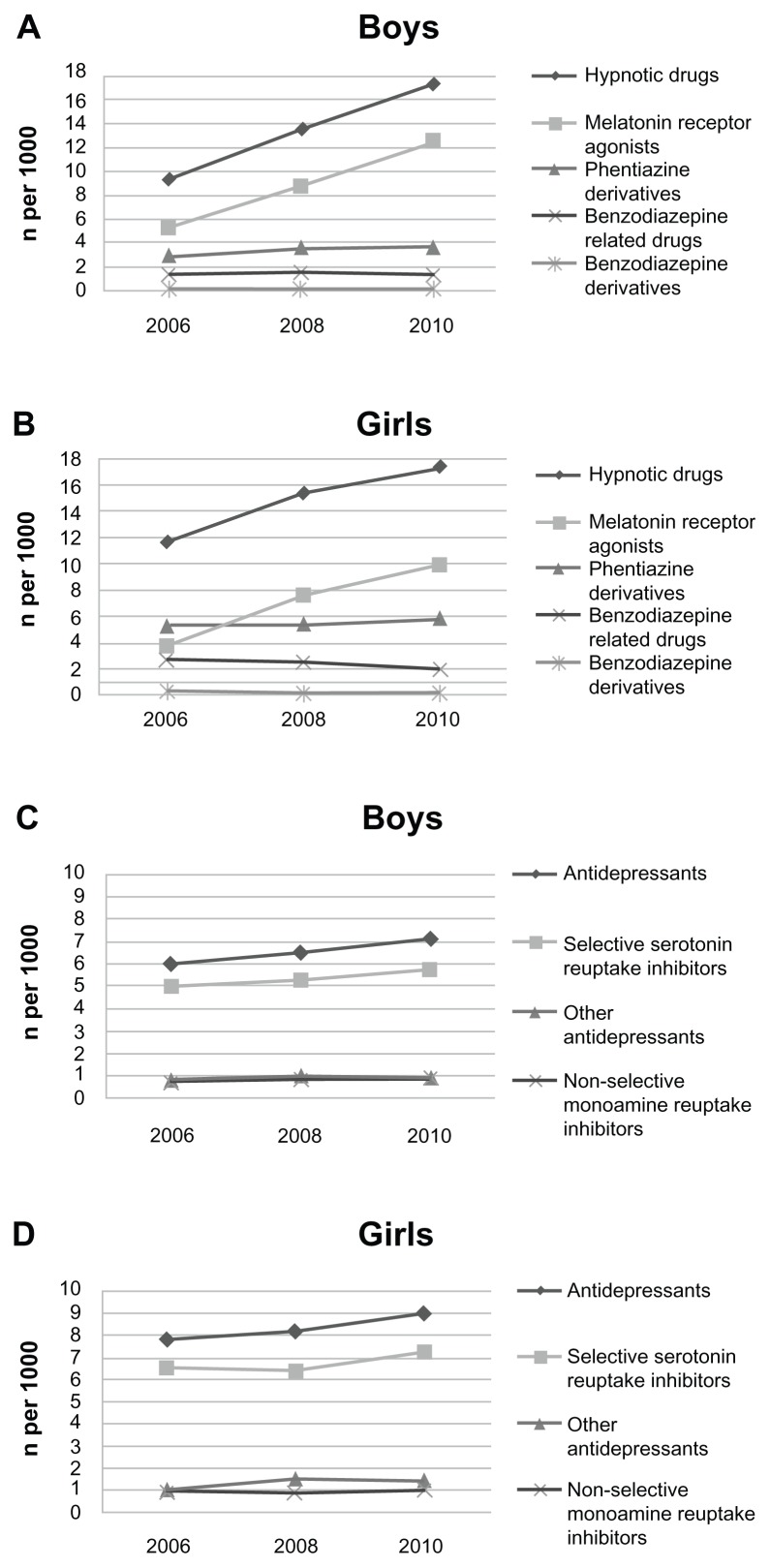

During the same period, the one-year prevalence of hypnotic drugs increased from 1338 (10.5 per 1000) to 2221 (17.3 per 1000), and its prevalence increased in both genders. Among boys, it nearly doubled from 9.3 to 17.3 per 1000 and among girls from 11.7 to 17.4 per 1000 (Table 2). Melatonin accounted for most of this increase (Figure 1A and B).

Figure 1.

(A and B) Norwegian prescription database showing one-year prevalence of hypnotic drug use by Norwegian boys and girls aged 15–16 years between 2004 and 2010. (C and D) One-year prevalence of antidepressant drug use by Norwegian boys and girls aged 15–16 years between 2004 and 2010.

Antidepressants were the second most often used psychotropic drugs in both genders. In 2006, 769 (6.0 per 1000) adolescents used antidepressants and 903 (7.0 per 1000) used them in 2010 (Table 2). On average, girls showed higher use of antidepressants than boys (Figure 1C and D). Use of anxiolytics was relatively low and stable for both genders throughout the study period (Table 2).

Annual amount of psychotropic drugs dispensed

The median annual amount of hypnotic drugs dispensed for boys was stable during 2006 and 2008 at 180 defined daily doses, but decreased to 90 defined daily doses in 2010. Hypnotic drug dispensing for girls showed the same trend, but was dispensed at lower levels (Table 3).

Table 3.

Norwegian prescription database showing annual amount of psychotropic drug use in terms of defined daily dose among boys and girls aged 15–16 years

| 2006 | 2008 | 2010 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||

| Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | ||||

|

|

|

|

||||

| Boys | Girls | Boys | Girls | Boys | Girls | |

| Hypnotic drugs (ATC code N05C + R06AD) | 180 (90–450) | 90 (16–237) | 180 (90–450) | 90 (21–270) | 90 (21–270) | 47 (21–180) |

| Benzodiazepine derivatives | 7 (3–38) | 20 (10–27) | 10 (3–20) | 20 (3–70) | 20 (10–163) | 20 (10–40) |

| Benzodiazepine-related drugs | 13 (7–30) | 10 (7–27) | 15 (7–30) | 13 (7–30) | 20 (10–30) | 13 (7–30) |

| Melatonin receptor agonists | 180 (90–540) | 180 (90–450) | 180 (90–540) | 180 (90–360) | 90 (42–357) | 90 (21–270) |

| Phenothiazine derivatives | 17 (8–46) | 8 (8–33) | 12 (8–33) | 8 (8–33) | 17 (8–33) | 8 (8–29) |

| Antidepressants (ATC code N05A) | 177 (84–350) | 140 (56–302) | 200 (90–392) | 130 (58–300) | 182 (90–322) | 139 (58–302) |

| Nonselective monoamine reuptake inhibitors | 13 (13–40) | 13 (13–30) | 33 (13–67) | 17 (13–27) | 17 (13–48) | 17 (13–33) |

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors | 200 (100–392) | 196 (98–379) | 234 (100–399) | 188 (100–336) | 198 (100–360) | 196 (98–364) |

| Other antidepressants | 45 (15–102–75) | 45 (15–87) | 45 (15–123) | 30 (15–84) | 60 (30–160) | 30 (15–100) |

| Anxiolytics (ATC code N05B) | 8 (3–17) | 8 (4–13) | 13 (5–27) | 13 (5–26) | 13 (10–25) | 13 (5–27) |

| Benzodiazepine derivatives | 10 (5–13) | 5 (4–10) | 8 (5–12) | 5 (5–10) | 20 (5–25) | 8 (5–13) |

| Diphenylmethane derivatives | 8 (3–19) | 8 (3–17) | 13 (13–33) | 13 (13–33) | 30 (13–33) | 13 (13–33) |

| Azaspirodecanedione derivatives | 48 (47) | 22 (6–218) | 133 (133–133) | 67 (50–83) | 42 (8–142) | |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; ATC code, Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification system.

Among the hypnotic drugs, melatonin receptor agonists (ATC code N05CH) were prescribed most often for both boys and girls, with an annual median amount dispensed of 180 defined daily doses through the period until 2010, when it decreased to 90 defined daily doses (Table 3).

Among the boys, the median annual amount of antidepressant drugs dispensed was relatively stable at 177–182 defined daily doses in the study period. Corresponding figures for girls were lower (Table 3). The substances used most often were the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (ATC code N06AB), being used almost equally by both genders throughout 2006–2010 (Figure 1C and D). Anxiolytic drugs had the lowest median annual amount dispensed, and were rarely used for adolescents (Table 3).

Follow-up of psychotropic drug use (2007–2010)

Among incident users of psychotropic drugs in 2007, 16.4% (234 of 1429) filled at least one annual psychotropic drug prescription in the period 2007–2010 (Table 4). Among those having an antidepressant dispensed in 2007, almost a quarter were still being dispensed antidepressants in 2010. Among incident users of hypnotic drugs in 2007, 8.4% still filled hypnotic drug prescriptions in 2010 (Table 4).

Table 4.

Norwegian prescription database showing long-term use* (%) of psychotropic drugs (2007–2010) among all Norwegian incident users aged 15–16 years in 2007

| 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Psychotropic category | 1429 | 100 | 600 | 42.0 | 345 | 24.1 | 234 | 16.4 |

| Hypnotic drugs (ATC code N05C + R06AD) | 1126 | 100 | 345 | 30.6 | 166 | 14.7 | 95 | 8.4 |

| Antidepressants (ATC code N06A) | 504 | 100 | 284 | 56.3 | 166 | 32.9 | 115 | 22.8 |

| Anxiolytics (ATC code N05B) | 312 | 100 | 38 | 12.2 | 15 | 4.8 | 6 | 1.9 |

Note:

Retrieval of at least one prescription of a psychotropic drug each year in the period 2007–2010 among incident users in 2007 ATC code.

Abbreviation: ATC code, Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification system.

Discussion

Overall, this nationwide study showed an increase in hypnotic drug use among adolescents between 2006 and 2010. Hypnotic drugs constituted 75% of all psychotropic drugs dispensed, and increased by 40% during the period, whereas use of anxiolytics and antidepressants was stable in this period. Other studies have shown similar trends in use of these psychotropic drugs over time, corresponding well with the results of our study.5,12,16,17 The most striking observation in the current study was the increase in use of melatonin, which accounted for most of the increase in hypnotic drug use. Melatonin is a hormone which helps to regulate other hormones in the body and maintain the body’s circadian rhythm.18 The annual amount of melatonin dispensed between 2007 and 2010 indicates more than sporadic use among adolescents. Fifty percent of the boys using melatonin received an annual amount corresponding to one defined daily dose every second day or more in 2006–2008, decreasing to every fourth day in 2010, and 25% filled melatonin prescriptions corresponding to use of more than one defined daily dose every day. Obviously, melatonin has acquired a major role in the treatment of adolescent sleep problems in Norway, parallel to observations in an earlier study.5 Treatment of young people with melatonin has been controversial, especially in the prepubertal years, because it may affect reproduction.19 Attention has been drawn to the effects of medication related to age, gender, and physical and psychological development. Using drugs during puberty may have permanent effects on the developing brain, especially developmental psychopathology. 19,20 In Norway, melatonin is indicated as monotherapy for short-term treatment of primary insomnia characterized by poor quality of sleep among patients aged 55 years and older.5 In spite of this, recent studies conclude that melatonin for treatment of adolescent insomnia is safe.21,22

Antidepressants were the most common psychotropic drug used by adolescents in the long-term. After 4 years, almost a quarter of incident users in 2007 still filled a prescription for antidepressants in 2010. This may be expected because treatment with antidepressants is recommended for some time. Girls were more often prescribed antidepressants than boys, possibly due to the fact that they are more likely to present with depressive or anxiety disorders and ask their physicians for help.23

Off-label use of antidepressants among adolescents is described as frequent, with most dispensing being unlicensed for this age group, but there are variations from country to country.12 The safety of antidepressants in adolescents is debatable, not only because of the increased risk of suicide,24 but also in view of the effects on neurological and behavioral development.25,26 The current study shows relatively stable prescription rates for antidepressants among adolescents aged 15–16 years in the 2006–2010 periods. In 2003, the European and Norwegian health authorities issued a series of warnings against use of antidepressants by adolescents, especially selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and venlafaxine. 27 As a consequence, the prescription rate decreased in the period 2004–2006.27 From our observations for 2010, it appears that the warnings have had some effect on prescribing in the long term.

Methodological strengths and limitations

An important strength of this study is its use of a comprehensive national prescription register, which eliminates errors in measurement of psychotropic drug use due to inadequate recall by respondents. Another advantage of using register-based information is that it circumvents the common problem of psychotropic drug use being underreported.28,29 However, lack of information on adherence is always an issue when reporting prescription data for drug use. We do not know how many of the drugs purchased were actually taken. In some countries, misuse has become a problem among adolescents. Furthermore, sharing prescription drugs, and getting prescription drugs from a relative or friend seems to be a trend.30 This may have led to underestimation or over-estimation of drug use in this study. Further, adolescents in hospitals and institutions are not registered in the Norwegian prescription database, so were not taken into account in our study. Another limitation is that we do not have any information on the indications for use of the study drugs.

Conclusion

This study shows an increase in hypnotic drug dispensing for adolescents in Norway in the period 2006–2010, mainly attributable to increasing use of melatonin. Furthermore, the amount of melatonin dispensed indicates more than sporadic use over longer periods, despite melatonin only being licensed in Norway for insomnia in patients 55 years and older. Use of antidepressants was highest among girls, although dispensing for both genders was stable throughout the study period.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Zito J, Safer D, DosReis S, et al. Psychotropic practice patterns for youth: a 10-year perspective. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157:17–25. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fegert J, Kolch M, Zito J, Glaeske G, Janhsen K. Antidepressant use in children and adolescents in Germany. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2006;16:197–206. doi: 10.1089/cap.2006.16.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Skurtveit S, Rosvold EO, Furu K. Use of psychotropic drugs in an urban adolescent population: the impact of health-related variables, lifestyle and sociodemographic factors. The Oslo Health Study 2000–2001. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety. 2005;14(4):277–283. doi: 10.1002/pds.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zoëga H, Baldursson G, Hrafnkelsson B, Almarsdóttir AB, Valdimarsdóttir U, Halldórsson M. Psychotropic Drug Use among Icelandic Children: A Nationwide Population-Based Study. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 2009;19(6):757–764. doi: 10.1089/cap.2009.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hartz I, Furu K, Bratlid T, Skurtveit S. Increase in use of hypnotic drugs among children and adolescents aged 0–17 years- a nationwide prescription database study. Pharmacoepidemiolgy and Drug Safety. 2010;19:293. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Myhrene Steffenak AK, Nordström G, Wilde-Larsson B, Skurtveit S, Furu K, Hartz I. Mental Distress and Subsequent Use of Psychotropic Drugs Among Adolescents – A Prospective Register Linkage Study. The Journal of adolescent health: official publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. 2012;50(6):578–587. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simeon JG, Wiggins DM, Williams E. World wide use of psychotropic drugs in child and adolescent psychiatric disorders. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 1995;19(3):455–465. doi: 10.1016/0278-5846(95)00026-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rothenberger A, Gerlach M, Dittmann RW. Psychotropic Drugs in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry – a New Era on the Horizon. Current Pharmaceutical Design. Jul;16(22):2395–2397. doi: 10.2174/138161210791959863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bazzano, et al. Off-label prescribing to children in the United States outpatient setting. Academic Pediatrics. 2009;9(2):81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Acquaviva E, Legleye S, Auleley GR, Deligne J, Carel D, Falissard BB. Psychotropic medication in the French child and adolescent population: prevalence estimation from health insurance data and national self-report survey data. Bmc Psychiatry. 2009 Nov;:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-9-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zito J, Safer D, Berg L, et al. A three-country comparison of psychotropic medication prevalence in youth. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health. 2008;2(1):26. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-2-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zito J, Tobi H, Berg L, et al. Antidepressant prevalence for youths: a multi-national comparison. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety. 2006;15:793–798. doi: 10.1002/pds.1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Furu K. Establishment of the nationwide Norwegian Prescription Database (NorPD) – new opportunities for research in pharmacoepidemiology in Norway. Norsk epidemiologi. 2008;18(2) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Who Collaborating Center for drug Statistics Methodology. The ATC/DDD Systen (Online) [Accessed March 23, 2011]. Available at: http://www.whocc.no/

- 15. http://statbank.ssb.no//statistikkbanken/default_fr.asp?PLanguage=1. Jun, 2012.

- 16.Hsia Y, Maclennan K. Rise in psychotropic drug prescribing in children and adolescents during 1992–2001: a population-based study in the UK. Eur J Epidemiol. 2009;24(4):211–216. doi: 10.1007/s10654-009-9321-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hansen E, Holstein B, Due P. Time trends in medicine use among adolescents in industrialised countries. European Journal of Public Health. 2003;13:43. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crowley SJ, Carskadon MA. Modifications to weekend recovery sleep delay circadian phase in older adolescents. Chronobiology International. 2010;27(7):1469–1492. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2010.503293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Srinivasan V, Spence WD, Pandi-Perumal SR, Zakharia R, Bhatnagar KP, Brzezinski A. Melatonin and human reproduction: Shedding light on the darkness hormone. Gynecological Endocrinology. 2009;25(12):779–785. doi: 10.3109/09513590903159649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sutherland ER, Ellison MC, Kraft M, Martin RJ. Elevated serum melatonin is associated with the nocturnal worsening of asthma. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2003;112(3):513–517. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(03)01717-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoebert MvdHK, van Geijlswijk IM, Smits MG. Long-term follow-up of melatonin treatment in children with ADHD and chronic sleep onset insomnia. J Pineal Res. 2009;47(1):1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2009.00681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Geijlswijk Ingeborg M, Mol Robert H, Egberts Toine CG, Smits MG. Evaluation of sleep, puberty and mental health in children with long-term melatonin treatment for chronic idiopathic childhood sleep onset insomnia. Psychopharmacology. 2011;216(1):111–120. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2202-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dekker, van Lang ND, Bongers IL, van der Ende J, Verhulst FC, et al. Developmental trajectories of depressive symptoms from early childhood to late adolescence: gender differences and adult outcome. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 48(7):657–666. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Olfson M, Shaffe D, Marcus SC, Greenberg T. Relationship Between Antidepressant Medication Treatment and Suicide in Adolescents. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(10):978–982. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.9.978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clavenna A, et al. Use of psychotropic medications in Italian children and adolescents. Eur J pediatr. 2007;166(4):399–347. doi: 10.1007/s00431-006-0244-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clavenna A, Bonati M, Rossi E, De Rosa M. Increase in non-evidence based use of antidepressants in children is cause for concern (letter) BMJ. 2004;328:711–712. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7441.711-c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bramnes, et al. Use of antidepressants among children and adolescents 2004 -06 - did the warnings lead to fewer prescriptions? [Antidepressiver hos barn og ungdom - førte advarsler til færre forskrivninger?]. Tidsskriftet for Den norske legeforening. 20, 127:2653–2655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Skurtveit S, Selmer R, Tverdal A, Furu K. The validity of self-reported prescription medication use among adolescents varied by therapeutic class. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2008;61(7):714–717. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nielsen MW, Søndergaard B, Kjøller M, Hansen EH. Agreement between self-reported data on medicine use and prescription records vary according to method of analysis and therapeutic group. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2008;61(9):919–924. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Apa-Hall P, Scwartz-Bloom RD, McConnell ES. The current state of teenage drug abuse: trend toward prescription drugs. The Journal of School Nursing, supplement. 2008:15. [Google Scholar]