Abstract

Aim

This study tests the hypothesis that DNA intercalation and electrophilic interactions can be exploited to noncovalently assemble doxorubicin in a viral protein nanoparticle designed to target and penetrate tumor cells through ligand-directed delivery. We further test whether this new paradigm of doxorubicin targeting shows therapeutic efficacy and safety in vitro and in vivo.

Materials & methods

We tested serum stability, tumor targeting and therapeutic efficacy in vitro and in vivo using biochemical, microscopy and cytotoxicity assays.

Results

Self-assembly formed approximately 10-nm diameter serum-stable nanoparticles that can target and ablate HER2+ tumors at >10× lower dose compared with untargeted doxorubicin, while sparing the heart after intravenous delivery. The targeted nanoparticle tested here allows doxorubicin potency to remain unaltered during assembly, transport and release into target cells, while avoiding peripheral tissue damage and enabling lower, and thus safer, drug dose for tumor killing.

Conclusion

This nanoparticle may be an improved alternative to chemical conjugates and signal-blocking antibodies for tumor-targeted treatment.

Keywords: doxorubicin, HER, herdox, nanoparticle, noncovalent, penton base, self-assembly, tumor targeting, viral capsid

Since its inception as a tumor-toxic agent, the anthracycline, doxorubicin (Dox), has remained a cornerstone of cancer treatment, despite potential cardiotoxicity at high levels [1]. In the absence of targeting, Dox permeates cell membranes and accumulates in the nucleus, where it can non-specifically insert between DNA base pairs and impair transcription [2]. Newer forms of Dox, either as an antibody-targeted drug or enclosed in liposomes, can reduce the high dose bolus required for tumor cell death [3,4], thus lessening cardiotoxicity. However, such approaches have encountered limitations in physiological stability [5,6], cellular uptake [7] and release into tumors [8].

We have previously developed the viral capsid-derived fusion protein, HerPBK10, which targets genes and corroles to cells displaying the EGF receptor HER, heterodimer (HER2/3 or HER2/4 subunits) [9–11]. HerPBK10 contains the receptor-binding domain of heregulin, whose direct binding to HER3 or HER4 is greatly enhanced by HER2 subunit amplification [12–14]. HER2 elevation typifies several types of tumors (known as HER2+ tumors), including glioma and ovarian, prostate and breast cancer [14–19], and is associated with metastasis and poor prognosis. HER2 signal-blocking antibodies, such as trastuzumab [20,21], have had limited efficacy in up to 70% of treated patients with HER2+ breast cancer [22], possibly due to aberrant intracellular pathways that may not respond to signal inhibition [23], while increased cardiac sensitivity due to HER2 signal blunting at the myocardium [24] has been associated with cardiomyopathy that is exacerbated by anthracyclines in treated patients [25]. By contrast, HerPBK10 circumvents signal inhibition as a means to modulate tumor growth by directly transporting drugs into the cell through ligation-triggered endocytosis [26], which HER2-targeted antibodies cannot do.

HerPBK10 can transport nucleic acid by electrophilic binding via a carboxy-terminal poly lysine. Whereas the compaction of plasmid DNA into soluble, decompactable particles is one of several obstacles for efficient nonviral gene delivery [27,28], oligonucleotide and siRNA delivery has been less daunting [29,30]. In all cases, endosomal release is necessary to permit both large [9,10] and small [30–32] nucleic acid translocation into the cytosol. Accordingly, HerPBK10 is a modification of the membrane-penetrating penton base (PB) protein, which is derived from the adenovirus capsid [9,10]. Soluble recombinant PB can recapitulate the early infection mechanism of the whole virus [30] while lacking cytopathic effects, thus enabling the gene and drug-delivery potential of PB-derived proteins, including HerPBK10. Unlike the whole virus, HerPBK10 itself does not induce neutralizing antibody formation upon repeat administration in immune-competent mice [11], further supporting its potential for therapeutic delivery.

This study tests the possibility of combining the nucleic acid binding activity of HerPBK10 with the DNA intercalating activity of Dox to form HerDox (Supplementary Figure S1, see online at www.futuremedicine.com/doi/suppl/10.2217/nnm.11.104), for the delivery of unaltered drug to tumors. Our studies show that HerDox self-assembly prevents nucleic acid degradation and Dox loss in serum, forming a nanoparticle that enables targeted HER2+ tumor cell killing in vitro, and in vivo while sparing the heart at >10× lower dose compared with untargeted Dox, and undergoing nuclease-independent Dox release after cell entry.

Materials & methods

Materials

Polyhistidine-tagged recombinant protein production and affinity chromatography purification is previously described [10]. The following respective 48 and 30 base oligonucleotide sequences, BglIIHis-5 (5′-GACTACAGA-TCTCATCATCATCATCATCATGAGCT-CAAGCAGGAATTC-3′) and LL A A-5 (5′-CGCCTGAGCAACGCGGC-GGGCATCCGCAAG-3′), and corresponding reverse complements (BglIIHis-3 and LLAA-3) were custom-synthesized by commercial sources. 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid-buffered saline (HBS) (20 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid, pH 7.5; 150 mM NaCl). Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Dox-HCl was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (MO, USA). AlexaFluor 680-labeling of PB was performed following manufacturer’s procedures (Invitrogen, CA, USA). Adenovirus 5 polyclonal antibody (recognizing the PB domain of HerPBK10) was obtained from Access Biomedical (CA, USA). Antihuman αvβ3 and αvβ5 antibodies (used at 1:1000 and 1:500, respectively, for immunofluorescence) were obtained from Chemicon/Millipore (MA, USA).

Cells

Human breast cancer cell lines (MDA-MB-435, MDA-MB-453, MDA-MB-231, MCF7, T47D and SKBR3), ovarian cancer (SKOV3), cervical carcinoma (HeLa) and glioma (U251, U87) origin were obtained directly from the National Cancer Institute repository (MD, USA) and American Type Culture Collection, maintained in DMEM, 10% fetal bovine serum under 5% C02, and immediately profiled for relative cell surface receptor subunit levels (Supplementary Figure S2). It is worth noting that while controversy in recent years over the possible melanoma origin of the MDA-MB-435 cell line has raised doubts over its suitability as a breast cancer model [33], the most recent studies indicate that this cell line, despite sharing M14 melanoma markers, is indeed of breast cancer origin [34].

Particle assembly

Double-stranded annealed complementary oligonucleotides (ds-oligo), BglIIHis or LLAA duplexes, were incubated with Dox at 1:16 or 1:10 molar ratio of DNA:Dox, respectively, at room temperature for 30 min. Ratios were chosen based on the theoretical number of Dox molecules bound at saturation. Unincorporated Dox was removed by centrifugation through 10 K molecular weight cut-off (mwco) filter membranes. DNA-Dox was then incubated with HerPBK10 (2 h on ice) at 9:1 or 6:1 molar ratio (BglIIHis or LLAA duplexes, respectively) of HerPBK10:DNA-Dox in HBS, followed by either (where indicated): size-exclusion HPLC (TSKgel G3000SW XL 7.8 mmID × 30 cm; TOSOH Bioscience, LLC, PA, USA) equilibrated with HBS (1 ml/min f low rate) to isolate HerDox from incompletely assembled components; or ultrafiltration as described earlier. Treatment doses reflect the Dox concentration in HerDox, which was assessed by extrapolating the measured absorbance (A480) or fluorescence (Ex480/Em590) against a Dox absorbance or fluorescence calibration curve (SpectraMax M2; Molecular Devices, CA, USA). It is worth noting HerDox comprising BglIIHis duplex was initially used in pilot and in vitro experiments. As we observed no detectable differences in Dox retention by BglIIHis and LLAA oligoduplexes (Supplementary Figure S3), the subsequent in vivo experiments were performed using HerDox comprising of LLA A duplexes.

Cryo-electron microscopy

Cryo-electron microscopy was performed by NanoImaging Services, Inc. (CA, USA) implementing the following procedures (provided by NanoImaging Services, Inc.): samples were preserved in vitrified ice supported by carbon-coated holey carbon films on 400 mesh copper grids. All samples were prepared by applying a 3-μl drop of undiluted sample suspension to a cleaned grid, blotting away with filter paper and immediately proceeding with vitrification in liquid ethane. Grids were stored under liquid nitrogen until transferred to the electron microscope for imaging. All grids were prepared the day the sample was delivered (complexes were assembled immediately before delivery). Electron microscopy was performed using an FEI Tecnai T12 electron microscope, operating at 120 KeV equipped with an FEI Eagle 4K × 4K charge-coupled device camera. Vitreous ice grids were transferred into the electron microscope using a stage that maintains the grids at below −170°C. Images of the grid were acquired at multiple scales to assess the overall distribution of the specimen. After identifying potentially suitable target areas for imaging at lower magnifications, higher magnification images were acquired at nominal magnifications of 52,000× (0.21 nm/pixel) and 21,000× (0.50 nm/pixel). The images were acquired at a nominal underfocus of −4 μm (52,000×) and −5 μm (21,000×) at electron doses of approximately 10–15 e/Å2.

Stability in blood/serum

To study stability in blood, HerDox or Dox (60 μM each) were incubated in equivalent volumes of whole blood (containing 0.5 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid to prevent coagulation and freshly collected from the aorta of an anesthetized mouse following Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved procedures) for up to 60 min at 37°C, followed by centrifugation through 10 K mwco filters. Retentate and filtrate fluorescences were extrapolated against a Dox calibration curve performed in blood plasma to correct for plasma-induced fluorescence shift. Blood alone showed negligible fluorescence. To assess protection from serum nucleases, the ds-oligo prebound by Dox, HerPBK10, or both was incubated for 20 min at 37°C in 100% mouse serum (Abcam, MA, USA) before polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide staining to visualize the DNA (Dox fluorescence was not visible on the gel at the concentrations used). Control conditions preventing digest include using heat-inactivated serum and 0°C incubation. To confirm particle retention of Dox in serum, Dox, DNA-Dox and HerDox were suspended in 100% mouse serum and fluorescence spectra measured before a 30 min incubation at 37°C, followed by ultrafiltration (10 K mwco). Filtrates were collected and membranes washed three times with HBS before collection and fluorescence measurement of retentates. All fluorescence spectra were obtained using a 515-nm cutoff filter.

In vitro targeting

For all in vitro treatments, cell lines were grown for approximately 36 h after plating (104/well in 96-well dishes) to allow receptor re-expression, followed by media replacement with new media containing indicated constructs in reduced volume at the indicated final molarities for 4 h with rocking, followed by supplementation with additional media and continued growth for the indicated time periods. Except for the experiments performed on the U251 glioma cells (that received a one-time treatment), cells received these treatments daily, while separate sets of wells were assessed for cell death by either metabolic assay (CellTiter 96; Promega Corporation, WI, USA) or crystal violet stain each day. Where indicated, cells received a competitive inhibitor (eHRG) [26] at 10× molar excess for 30 min to 1 h at 4°C before treatment. Treatment of mixed (HER2+/HER2−) cell cultures with HerDox or Dox (0.5 uM), and cell surface receptor subunit level determination were performed as described previously [11].

In vitro imaging

General procedures

MDA-MB-435 cells were plated approximately 36 h before receiving HerDox or Dox (0.5 μM final Dox concentration) in fresh media containing the indicated constructs. For live cell assays, the cells (plated in chambers) were imaged at the indicated time points after treatment, under brightfield or differential interference contrast microscopy (where indicated) and fluorescence modes to identify the cell structure and Dox fluorescence, respectively. For fixed cell assays, the cells were plated on cover slips in 24-well plates (1 × 105 cells/well) approximately 36 h before receiving HerDox or Dox in fresh complete media at 37°C, and separate samples fixed and processed for immunofluorescence against HerPBK10 following established procedures [30]. A Leica SP2 laser-scanning confocal fluorescence microscope was used for fixed and live cell imaging.

Cytosolic nuclease digest assay

MDA-MB-435 cell lysates were prepared by washing detached cells twice with PBS followed by suspension in 0.1 ml lysis buffer (320 mM sucrose, 20 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid, 3 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride)/3 × 106 cells, shearing via passage 20× through a 22G needle, then freeze–thaw 3× (liquid N2/37°C), and centrifuged (14,000 × g) for 15 min before extracting the supernatant. Duplex or approximately 3 kb plasmid (~ 150 ng) was incubated with lysate at 1:3 DNA:lysate volume ratio up to 45 min at 37°C, followed by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and ethidium bromide gel staining for 30 min before UV detection of DNA bands.

In vivo procedures

Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee-approval was obtained for all in vivo and euthanasia procedures in this study. Female immunodeficient (nu/nu) mice (6–8 weeks; Charles River Laboratories International, MA, USA) received subcutaneous bilateral flank injections of 1 × 107 indicated cells and were monitored until tumors reached approximately 200–300 mm3, at which point the following treatments were initiated. To assess tumor-targeting in vivo, tumor-bearing mice received a single intravenous injection (via tail vein) injection of HerDox or Dox (0.02 mg/kg final Dox dose) and imaged at the indicated time-points after injection using a custom small animal imager (described below) adjusted to detect Dox fluorescence. After the final time-point, mice were euthanized and tissues were harvested for biodistribution analysis. To assess pharmacokinetics, separate groups of tumor-bearing mice receiving a single intravenous injection of HerDox were euthanized at the indicated time points and tissues harvested for fluorescence acquisition using the same custom imager described below. To assess therapeutic efficacy, a new group of tumor-bearing mice received daily intravenous (tail vein) injections of HerDox or Dox at indicated doses for 7 days followed by continued monitoring of tumor volumes (assessed by measuring tumor length and width using calipers, and applying LxW2), animal weights and heart function. Feasibility of repeated injections in the tail vein is demonstrated at [101]. Cardiac function in anesthetized mice was evaluated by a Vevo 770 High-Frequency Ultrasound system (VisualSonics, Toronto, Canada). Heart rate and body temperature were monitored. Superficial hair was removed from the region of interest with a depilatory cream (Nair®) before imaging. The 2D guided M-mode images of the left ventricle were obtained in the short-axis view at the papillary level with the mouse in the supine position. All primary measurements were traced manually and digitized by goal-directed software installed within the echocardiograph. Three beats were averaged for each measurement. All measurements were carried out from leading edge to leading edge according to the American Society of Echocardiography guidelines. At animal study completion, tissue harvested from euthanized mice were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde/PBS at 4°C for 24 h followed by transfer into 20% sucrose/PBS and storage at −80°C before immunohistochemical processing. Specimens and hematoxylin/eosin staining were prepared by AML Laboratories, Inc. (MD, USA).

In vivo imaging

A customized macroillumination and detection system [35–37] was used for in vivo and tissue imaging. Dox was excited with the 488-nm line of a Coherent Innova ArKr laser. Laser light (300 mW) was directed into a light-tight box via mirrors and expanded by an engineered circular tophat diffuser (Thorlabs ED1-C20) to a uniform circular beam of approximately 15 cm in diameter. The incidence angle to the vertical plane was approximately 15θ. Fluorescence light was collected via a telecentric lens (Melles-Griot 59LGG925 base lens with a 59LGL428 attachment lens), which can operate at f/#2, has a magnification of 0.9, a working distance of 257 mm and a depth of field of 81.5 mm. A bandpass filter (580 nm with a 50-nm bandwidth) was used in the emission pathway to reject the excitation light. Images showing fluorescence intensity (FI) were collected with a cooled CCD camera (Hamamatsu ORCA-ER). Where indicated, a Maestro imager was used (Cedars-Sinai Imaging Core Facility, CA, USA). ImageJ was used to calculate average fluorescence intensities of the overall region of each selected tissue.

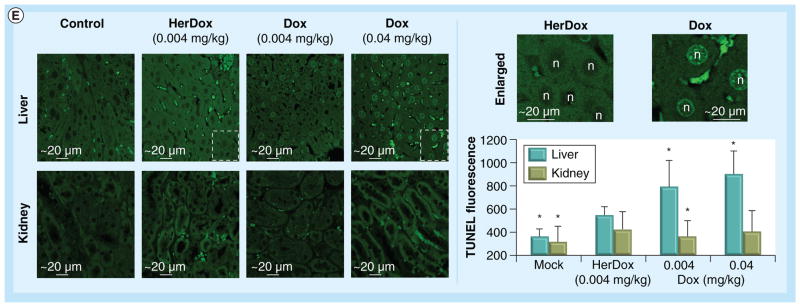

TUNEL staining & confocal fluorescence imaging of tissue sections

Fixed, sectioned tissues were processed by incubation in a dry 60°C oven for 1 h followed by sequential submersion in xylenes five times for 4 min, then hydration in 100, 95, 90, 80 and 70% ethanol for 3 min, two times each and final submersion in water. After Proteinase K (20 ug/ml in 10mM Tris, pH 7.8) incubation and rinsing in PBS, sections were treated for TUNEL staining following the manufacturer’s instructions (In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit, Fluorescein; Roche Applied Science, IN, USA) and assessed by confocal fluorescence imaging. Here, ten TUNEL images at different locations per tissue were acquired using a Leica confocal SPE microscope (20×, excitation: 488 nm, and emission: 530 nm). Central regions of each tissue were imaged to avoid fixation artifacts. Nuclear fluorescence intensities, reflective of DNA fragmentation, were measured and averaged using ImageJ.

Statistical analyses

All data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation of indicated sample sizes, and were analyzed by a one-way ANOVA test followed by a Tukey post-hoc analysis, with the level of significance set at p = 0.05.

Results

Particle assembly facilitates serum-stability

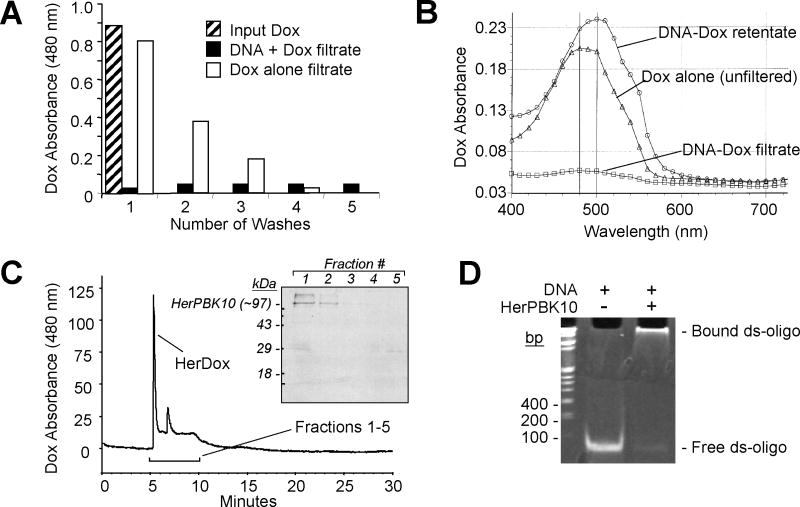

Formation of a ds-oligo by annealing complementary nucleic acid sequences enabled Dox intercalation to form DNA-Dox, which remained intact during ultrafiltration to separate bound from unbound Dox. Whereas free Dox passed through the filter membrane and was detectable in the filtrate, Dox was nearly undetectable in DNA-Dox filtrates, even with subsequent washes to remove any free/released Dox (Figure 1A). In agreement the maximum absorbance wavelength (λmax) of DNA-Dox retentate coincided with unfiltered Dox (with the DNA binding slightly shifting the λmax), whereas no such absorbance was detectable in the filtrate (Figure 1B). Incubating the retentate with HerPBK10 formed the product, HerDox, in which the majority of Dox absorbance was detected during size-exclusion HPLC coeluted with HerPBK10 (Figure 1C). Electrophoretic mobility shift analysis confirmed that HerPBK10 directly bound the DNA duplex (Figure 1D). Cryo-electron microscope imaging showed that HerDox formed mostly round approximately 10-nm diameter particles in addition to some larger amorphous aggregates (Figure 2). Storage at different incubation times and temperatures (4°C, RT or 37°C over a 12-day period) yielded no detectable Dox release from HerDox (Supplementary Figure S4A).

Figure 1. Her-doxorubicin assembly.

(A) Assembly of DNA-Dox. A480 (Dox absorbance maximum) of DNA-Dox and free Dox filtrates during assembly. Input Dox, A480 before filtration. (B) Absorbance spectra of DNA-Dox retentate and filtrate after assembly.

(C) HerPBK10 binding to DNA–Dox. HPLC graph shows eluates (detected based on Dox absorbance) collected over time from a size exclusion column. Inset, SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting of HPLC fractions collected at 6–10 min (fractions 1–5). Immunodetection of HerPBK10 was performed as described previously [10]. In subsequent experiments, HerDox was collected from the 6-min peak.

(D) Electrophoretic mobility shift assay showing HerPBK10 binding to ds-oligo. Duplex (150 ng) was incubated with HerPBK10 (4 μg) for 10 min at room temperature before 15% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, followed by ethidium bromide stain (30 min) before UV visualization.

Dox: Doxorubicin; ds-oligo: Double-stranded annealed complementary oligonucleotides.

Figure 2. Cryo-electron microscopy of Her-doxorubicin particles.

Micrographs show the formation of small particles that are mostly round (delineated regions) or with less defined shape (left arrows), as well as larger aggregates (right arrow). Macro aggregates up to 200 nm and larger were also evident (not shown). Numbered areas highlighting representative round particles are enlarged in right panels. Sample preparation and imaging was performed by NanoImaging Services, Inc., CA, USA.

To predict stability in vivo, ultrafiltration was used to determine whether incubation in blood induced Dox release from the complex, which would be detected by a partitioning of Dox fluorescence into the filtrates (as exhibited by free Dox after a 1-h incubation at 37°C in freshly collected blood from mice) (Figure 3A). In contrast to free Dox, HerDox showed no detectable fluorescence in filtrates or loss from retentates, suggesting that the complex retains Dox even in blood (Figure 3A). In agreement, HerDox incubated up to 24h in complete cell culture media exhibited no loss of Dox from the complex (Supplementary Figures S4B & C), suggesting that HerDox retains stability under physiological conditions.

Figure 3. Stability in serum.

(A) Stability in blood. Retentate and filtrate fluorescences of HerDox or Dox after 1 h incubation in mouse blood, saline or 0.5 mM EDTA at 37°C, followed by ultrafiltration (n = 3). (B) Representative gels (n = 4 per experiment) showing DNA protection in serum. The double-stranded oligonucleotide-oligo prebound by Dox (+Dox), HerPBK10 (+HerPBK10), or both was incubated for 20 min in 100% mouse serum (Abcam, MA, USA) before polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide staining to visualize the DNA (Dox fluorescence was not visible on the gel at the concentrations used). Control conditions preventing digest include using HI serum and 0°C incubation. (C) Assessing Dox retention in serum. Fluorescence spectra of Dox, DNA-Dox and HerDox before (input) and after incubation in 100% mouse serum followed by ultrafiltration and measurement of retentates.

Dox: Doxorubicin; EDTA: Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid; HI: Heat-inactivated.

To identify the factors contributing to serum stability, we first examined ds-oligo vulnerability to degradation by serum nucleases. Naked duplex in mouse serum underwent degradation within 20 min of exposure, while preassembly with HerPBK10 or heat inactivation of the serum prevented this (Figure 3B), suggesting that HerPBK10 binding protects the duplex from serum-mediated degradation. Preintercalation by Dox also partially protected the DNA from serum degradation (Figure 3B), thus preventing its own release in serum. To validate these findings, we subjected HerDox and controls to ultrafiltration after serum exposure and assessed the level of Dox loss from retentates. The majority (~70%) of free Dox was lost from Dox-only retentates, whereas no Dox loss was detected from HerDox or DNA-Dox retentates (Figure 3C). An assessment of serum-binding activity suggests that the remaining approximately 30% of free Dox is likely to undergo relatively weak or nonspecific binding to serum proteins (Supplementary Figure S4D). Consistent with the gel assays, Dox retention in serum-exposed DNA-Dox suggested that this complex was equally resistant as HerDox to serum nucleases and/or Dox loss. Altogether, these findings indicate that both HerPBK10 binding and Dox intercalation protects the DNA from serum-mediated degradation, which in turn prevents serum-mediated Dox release from HerDox.

HerDox toxicity in vitro is targeted to HER2+ cells & correlates with HER2 subunit levels

HerDox induced significant toxicity to HER2+ (MDA-MB-435) but not HER 2- (MDA-MB-231) human breast cancer cells in separate cell cultures, whereas Dox exhibited no preference, and HerPBK10 alone had no effect on proliferation or survival of either cell line (Figure 4A). The competitive inhibitor, eHRG, prevented HER2+ cell killing by HerDox (Figure 4B), suggesting that HerDox bound and entered cells via the heregulin receptor, HER.

Figure 4. Targeted toxicity in vitro.

All treatments, n = 3. (A) Comparing cytotoxicity with HER2+ (MDA-MB-435) and HER2− (MDA-MB-231) cells in separate cultures. Relative survival (as a percentage of untreated cells) on day 3 of treatment. (B) Micrograph of live cells after treatment. Control, mock (4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid buffered saline) treatment. (C) Receptor specificity of cytotoxicity. Relative survival of MDA-MB-435 cells receiving HerDox −/+ competing ligand (eHRG). (D) Toxicity to cells displaying differential HER2. Cytotoxicities from HerDox titrations were assessed on each cell line by metabolic assay and confirmed by crystal violet stain on day 3 of treatment. CD50 values (shown in log scale) were determined by nonlinear regression analyses of HerDox killing curves using GraphPad Prism. The relative HER2 level of each cell line (obtained in Supplementary Figure 2) is shown next to each CD50 value. (E) Targeting in a mixed MDA-MB-435 (HER2+,GFP-)/MDA-MB-231(HER2−,GFP+) cell culture. Survival was determined by calculating the relative doubling time of experimental cells normalized by mock-treated cells based on crystal violet stains (total cells) and GFP fluorescence (MDA-MB-231 cells), and applying DTMDA-MB-435 = DTTotal − DTMDA-MB-231 as described previously [11]. Relative survival is shown for day 2 of treatment. (F) Targeted glioma cell death in vitro. U251 cells were treated once with the indicated HerDox (and competitive inhibitor where indicated) or Dox doses and measured for cell survival at the indicated time points after treatment.

*p < 0.05 compared with mock.

DT: Doubling time; Dox: Doxorubicin; Un: Untreated.

To assess the contribution of HER2 to therapeutic efficacy in vitro, we determined HerDox CD50 on selected human tumor lines displaying HER2 at relatively high (SKBR3), moderate (MDA-MB-435, MDA-MB-453, HeLa), and low to undetectable (MDA-MB-231) levels, according to our receptor subunit profiling of a cell line panel (Supplementary Figure S2). In support of the influence of HER2 on ligand-receptor affinity, HerDox CD50 on selected lines inversely correlated with cell surface HER2 on high (SKBR3, 0.056 ± 0.017 μM) and low HER2 cell lines (MDA-MB-231, >8 μM), while intermediate sensitivities associated with intermediate HER2 levels (0.3–0.8 μM) (Figure 4C ; note CD50 is shown on a log scale).

To confirm selectivity for HER2+ cells and add a further targeting challenge, HerDox was added to HER2+ and HER2− cocultured breast cancer cells, distinguished from one another by GFP tagging of the HER2− cell line, as described previously [11]. While Dox alone exhibited reduced efficacy on a mixed cell culture, HerDox substantially reduced HER2+ but not HER2− cell growth (Figure 4D).

Finally, we examined cytotoxicity to HER2+ glioma cells. In vivo, glioma require invasive localized procedures that necessitate high efficacy at low treatment frequency while still benefiting from the tumor-retention aspects of targeting. Taking this requirement into consideration, we exposed U251 human glioma cells in vitro (which display higher surface HER2 and similar surface HER3/4 subunit levels compared with MDA-MB-435 cells; Supplementary Figure S2) to a single dose of HerDox in vitro, which induced nearly complete cell death while an equivalent dose of Dox alone was less effective (75–80% with cell death by Dox in comparison to 96–99% cell death by HerDox) (Figure 4E). Cell death prevention by eHRG confirmed receptor-specific delivery by HerDox (Figure 4E). Notably, the sensitivity of this tumor line to a single dose is consistent with the earlier CD50 studies showing that high HER2 expression correlates with lower required dosage for therapeutic efficacy (Figure 4C).

Dox is released after cell uptake

A microscopic examination of treated MDA-MB-435 cells showed that while untargeted Dox was detectable at the nuclear periphery immediately after administration (consistent with its ability to permeate the plasma membrane and target the nucleus), HerDox appeared mostly at the cell periphery early after administration and exhibited nuclear accumulation by 60 min (FIGURE 5A), consistent with a cell entry mechanism that relies on initial binding at the cell surface. By further contrast, HerDox showed a nucleolar and cytosolic accumulation in live cells in comparison with the typical nuclear accumulation of untargeted Dox (Figure 5C). The ability to visualize nuclear Dox fluorescence after cell exposure to free Dox has been used frequently to detect Dox uptake in cells, and has been attributed to interaction with histones [38]. To determine whether these localization differences indicate that Dox remains attached to HerPBK10 during uptake, we used a counterstain for HerPBK10. At 15 min of uptake, HerPBK10 mostly colocalized with Dox, suggesting that a considerable population of HerDox is still intact, although some nuclear accumulation of Dox is already visible (Figure 5B). At 30 and 60 min, increasing levels of Dox accumulated in the nucleus while the majority of HerPBK10 remained in the cytoplasm (Figure 5B), suggesting that Dox is released from HerPBK10 after uptake.

Figure 5. Intracellular doxorubicin release.

HerDox and Dox (0.5 μM final Dox concentration) uptake and trafficking, assessed in (A & B) fixed and (C) live MDA-MB-435 cells. (A) Uptake pattern of Dox fluorescence (red) when administered as free Dox or HerDox. (B) HerPBK10 (green) and Dox (red) destinations after HerDox uptake. (C) Live MDA-MB-435 cells after incubation with HerDox or Dox for 1 h, followed by washing. Dox fluorescence (magenta) is overlaid on differential interference contrast images. (D) Double-stranded oligo stability in cytosolic lysates. Gels show ethidium bromide-staining of duplex and 3-kb plasmid after incubation with either lysate or 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid-buffered saline (-lysate). Relaxed (nicked) and supercoiled plasmid forms are indicated.

Dox: Doxorubicin; ds-oligo: Double-stranded annealed complementary oligonucleotides; SC: Supercoiled DNA.

To test whether intracellular Dox release is facilitated by cytosolic nuclease degradation of the DNA, we assessed the vulnerability of ds-oligo to cytosolic lysates, and observed that whereas a control plasmid underwent DNA nicking, the duplex remained undigested (Figure 5D). These findings suggest that post-entry Dox separation from HerPBK10 occurs through a nuclease-free displacement mechanism. Hence, we cannot rule out the possibility that Dox is still bound to the ds-oligo during nuclear entry.

HerDox targets HER2+ tumor cells in vivo

MDA-MB-435 tumor-bearing mice were imaged live after a single tail vein injection of HerDox, in order to visualize tumor-targeting ability in vivo. The imaging showed tumor-accumulation of HerDox by 20 min, where it remained detectable for up to 100 min (Figure 6A). The maximum FI measured in tissues harvested at approximately 3 h after injection showed that HerDox exhibited preferential tumor accumulation compared with other tissue: liver and kidney FIs were 45 and 65% lower than tumors, respectively, while the heart, spleen, lungs and skeletal muscle, exhibited no detectable fluorescence (Figures 6B & 6C). By contrast, Dox exhibited higher accumulation in all other nontumor tissues compared with HerDox, while tumor-accumulation was nearly 50% lower than HerDox and equated liver and kidney FIs (Figure 6C). Pharmacokinetics studies suggested that HerDox underwent rapid kidney entry by 10 min that decreased over time, whereas tumor-preferential accumulation continued to increase within 40 min and remained considerably higher (500–1000 fluorescence units higher/tissue) up to 24 h compared with normal tissue (heart, liver, muscle, spleen, lung and kidneys) (Figure 6D). This pattern contrasted with that observed in mice receiving untargeted Dox, which showed no preferential accumulation of Dox in tumors over other tissue, while tumor-accumulated Dox was substantially lower (by 1000 fluorescence units) compared with HerDox. As an additional comparison, HerDox and Dox were delivered intravenously in mice bearing U87 human glioma tumors (Figure 6D), which display approximately 50% lower level of HER subunits compared with MDA-MB-435 cells (Supplementary Figure S2). In these mice, HerDox delivery to U87 tumors was approximately 50% lower with reduced contrast between tumor and normal (i.e., kidney and liver) tissue compared with MDA-MB-435 tumor-bearing mice (Figure 6D). Nontargeted Dox distribution to nontumor tissue in these mice was similar to that in the MDA-MB-435 tumor-bearing mice, while delivery to the tumors was actually slightly higher (200–300 fluorescence units per tissue). Altogether, these findings indicate that HerDox preferentially accumulates in HER2+ tumors over nontumor tissue and over tumors expressing lower HER levels.

Figure 6. Preferential targeting to HER2+ tumors.

Tumor-bearing mice were intravenously injected with HerDox or Dox and (A) imaged with a custom small animal imager adjusted to detect Dox fluorescence (see Materials & methods), or (B–D) euthanized, and tissues harvested at indicated time points for biodistribution and pharmacokinetic analyses. (A) Live mouse imaging of HerDox at indicated time points after injection. Tumors are indicated by the arrows. (B–C) Comparative biodistribution of HerDox and Dox in tissues harvested at 3 h postinjection. (B) Imaging of biodistribution in harvested tissues. Pseudocolored fluorescence intensity (FI) corresponds to the color bar. The maximum represents the highest FI. (C) Quantification of HerDox and Dox biodistribution, showing Dox FI/tissue.

Dox: Doxorubicin.

Tumor-bearing mice were intravenously injected with HerDox or Dox and (A) imaged with a custom small animal imager adjusted to detect Dox fluorescence (see Materials & methods), or (B–D) euthanized, and tissues harvested at indicated time points for biodistribution and pharmacokinetic analyses. (D) Comparative pharmacokinetics of HerDox and Dox in mice with tumors expressing differential HER2. Tissues were harvested from independently injected mice euthanized at indicated time points after injection and fluorescence intensity/tissue acquired using a small animal imaging system as described (see Materials & methods).

Dox: Doxorubicin.

HerDox ablates tumor growth & is nontoxic to the heart

To assess therapeutic efficacy in vivo, MDA- MB-435 tumor-bearing mice received daily intravenous injections of HerDox for 7 days while tumor volumes were measured after administration (feasibility of daily intravenous injections is demonstrated in the Materials & methods section and Supplementary Figure S5). HerDox treatment resulted in ablation of tumor growth, which contrasted with the low efficacy by the equivalent Dox dose, while HerPBK10 alone and saline had no effect on tumor growth (Figure 7A). Importantly, 10× higher Dox dose was required to approach the tumor ablation of HerDox, but was still slightly less effective. Mice did not experience detectable weight loss (Figure 7B), suggesting that treatments did not affect general health; however, echocardiography showed signs of Dox-induced cardiac dysfunction that is not detectable in HerDox-treated mice: whereas Dox induced modest to marked reductions in stroke volume, cardiac output, and left ventricular internal dimension and volume, HerDox had no effect on these measurements, which appeared similar to mock (saline)-treated mice (Figure 7D). Myocardia from both saline and HerDox-treated mice exhibited normal cardiac morphology, whereas those from Dox-treated mice exhibited myo fibrillar degeneration, typifying Dox-induced cardiotoxicity (Figure 7C) [39,40]. Whereas in vivo imaging showed that residual levels of HerDox accumulated in the liver and kidney (Figure 6); TUNEL staining of both organs showed that Dox induced marked apoptosis in the liver, whereas HerDox did not (Figure 7E). Neither Dox nor HerDox showed substantial apoptosis in the kidney (Figure 7E).

Figure 7. HerDox induces tumor-targeted growth ablation while sparing the heart after intravenous delivery.

Comparison of HerDox (0.004 mg/kg) and Dox (0.004 or 0.04 mg/kg, where indicated) on (A) tumor growth (n = 8–10 tumors per treatment); (B) animal weight (n = 4–5 mice/treatment group); (C) cardiac tissue; (D) cardiac function (n = 3 mice/treatment group); and (E) liver and kidney tissue. Day 0 in (A & B) corresponds to 3 days before tail vein injections. Control (saline-injected) mice were euthanized early due to tumor ulceration, in compliance with Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee policy. Tumor growth in (A) was obtained by measuring tumor volumes (see Materials & methods). (C) Histology of myocardia from treated mice. Micrographs show representative hematoxylin and eosin-stained specimens from treated mice (40× magnification). (D) Echocardiography of mice obtained at 25 days following injections. *p < 0.05, compared with mock treatment (intravenous delivery of saline at equivalent volume to HerDox). (B–D) Results were obtained from mice receiving 0.004 mg/kg doses of Dox or HerDox. HerPBK10 dose equates HerDox protein concentration.

CO: Cardiac output; d: Diastolic; Dox: Doxorubicin; LV vol: Left ventricular volume; LVID: Left ventricular internal dimension; s: Systolic; SV: Stroke volume.

Comparison of HerDox (0.004 mg/kg) and Dox (0.004 or 0.04 mg/kg, where indicated) on (E) liver and kidney tissue. (E) TUNEL staining and quantification in liver and kidney tissue obtained from treated mice. Micrographs obtained at 20× magnification (left set of panels) show fluorescently stained nuclei in apoptotic cells (delineated areas are enlarged in micrographs to the right). Graph summarizes relative fluorescence intensities of each treated tissue (n > 200 fields per treatment). The quantification procedure is described in the Materials & methods section.

*p < 0.0001 compared with each corresponding HerDox treatment.

Dox: Doxorubicin.

Discussion

These studies show that the nucleic acid binding activity of HerPBK10 combined with the DNA intercalating activity of Dox to form the serum-stable nanoparticle, HerDox, effectively targets unaltered drug to HER2+ tumor cells in vitro and in vivo while sparing normal tissue, and undergoes nuclease-independent Dox release after cell entry (Supplementary Figure S6).

Drug retention and nuclease resistance of the DNA in HerDox combined with competitively-inhibited receptor binding places the payloads and ligands in solvent-protected and solvent-exposed positions, respectively, thus resembling a viral capsid-like particle (Supplementary Figure S1), which we have observed under cryo-electron microscopy (Figure 2). The selective targeted toxicity to HER2+ cells in both separate and mixed cultures reiterates our earlier findings in which we used HerPBK10 to target toxic gallium-metallated corroles to HER2+ tumors [11]. Here, Dox alone was less effective in mixed (in comparison with separate) cell cultures. Chemoresistance-enhancing intercellular interactions that take place in a heterogeneous environment [41,42] may explain the reduced response to Dox alone in the mixed cultures, which HerDox apparently overcomes, thus raising the possibility that HerDox may be used to circumvent drug resistance (a prospect that is under current investigation). This may be facilitated by the distinct intracellular trafficking taking place after cell uptake, which is consistent with other studies indicating that subcellular destination influences the avoidance of drug export [43]. Indeed, it has been suggested that endosomal encapsulation and transit evades cellular efflux systems normally recognizing cytosolic drug [44].

Studies on nonviral gene delivery have shown that cytosolic nucleases can digest naked DNA in the cytoplasm [45,46], and hence could be responsible here for intracellular release of Dox from HerDox. However, the resistance of the naked ds-oligo to cytosolic nuclease digest rules out this possibility, indicating that Dox separates from HerPBK10 either as a free molecule (by nuclease-independent means) or still bound to the ds-oligo (i.e., as DNA-Dox). The latter is supported by studies elsewhere showing that anionic molecules in the cytosol can displace oligonucleotides from cationic liposomes [47]. Indeed, the differential subcellular distribution of Dox when delivered via HerDox compared with untargeted Dox (Figure 5C) suggests that the ds-oligo may influence the intracellular destination of, and thus may still be bound to, Dox after its release from HerPBK10. The nucleolar accumulation could result from recognition by nucleolar-targeted proteins that are normally involved in small nucleolar RNA processing [48], though no obvious sequence matches arise between the oligonucleotide sequences used here and the C/D box and Cup motifs found on small nucleolar RNA [49]. Whether nucleolar accumulation contributes to the enhanced toxicity of the targeted complex is unknown but could be examined by testing a variety of duplexes with different sequences. Notably, there is no detectable difference between the Dox loading ability of 30 and 48 bp duplexes, which share no sequence identity (Supplementary Figure S3). Our ongoing studies will better determine the mechanisms contributing to the intracellular dynamics of HerDox observed here after cell entry. The ability of targeting to lower effective drug dose is not a new concept. While untargeted drugs are often tested at the maximum tolerated dose (~5–10 mg/kg for Dox), vascular targeting has enabled eight- to ten-fold lower Dox to potentiate the growth of melanoma and lymphoma tumors in mice [50], and folate receptor-targeting has enabled conjugated methotrexate to be used at over fourfold lower dose compared with free drug for human carcinoma xenografts [51]. The in vivo doses used in the present study were based on the lowest effective doses of HerDox facilitating targeted toxicity in vitro (equating ~1–0.1 μM). These doses are sufficient to mediate tumor-targeted toxicity while avoiding off-target damage as much as possible, especially in light of the chronic administration used in our treatment regimen.

The in vivo targeting observed here shows that the preferential accumulation of HerDox in HER2+ (MDA-MB-435) tumors over low HER2-expressing (U87) tumors is concomitant with HER2 surface levels. While it is possible that differential vascularization may account for these differences, untargeted Dox actually showed slightly higher delivery to the U87 tumors, while delivery to nontumor tissues was similar between MDA-MB-435 and U87 tumor-bearing mice. Moreover, tumor-accumulated HerDox was retained in MDA-MB-435 tumors up to 24 h after delivery. Thus, while enhanced permeability and retention, facilitated by leaky tumor vasculature, is a phenomenon that can facilitate tumor accumulation of many types of untargeted small molecules [52], the findings shown here suggest that receptor level additionally influences ligand-directed delivery and tumor retention in vivo.

The tumor preference and avoidance of cardiac damage by HerDox may be attributable, in part, to the requirement that HER2 elevation increases ligand binding affinity of HER3 or HER4 subunits [12,13], hence tissue displaying low or normal HER2 levels are likely bypassed, in contrast to HER2-targeted antibodies that affect HER2 expressed on the myocardium as well as on tumors. This may illustrate an obstacle of targeting antibody selection whereby high-affinity clones are isolated that can recognize even normal or low levels of epitopes, and hence affect normal, ‘off-target’ tissue in vivo. We also attribute the therapeutic efficacy seen here to the rapid receptor-mediated uptake induced by HER ligand binding [26,53], which we have shown in previous studies enables DNA [10] and corrole [11,54] uptake into target cells. Drug-targeting antibodies directed at HER2 extracellular epitopes do not necessarily induce internalization, thus limiting potency [7] and illustrating that targeting is not enough. Likewise, while Dox-loaded liposomes can accumulate in tumors [55] via leaky tumor vasculature [56], release likely occurs at the cell surface, assisted by the acidic microenvironment, lipase release from dying cells and enzyme and oxidizing agent release from infiltrating inflammatory cells [57]. While targeting such liposomes by the trastuzumab Fab’ fragment improves tumor-directed delivery [55], whether these undergo receptor-mediated uptake or affect cardiac tissue is unclear.

HerPBK10 contains endosomal escape activity to facilitate payload access to cytosolic and nuclear targets [9–11,30,54], as necessitated by the intercalation of Dox in the ds-oligo. The potential integrin binding motifs inherent on the PB domain of HerPBK10 are retained but nonfunctional [10], likely due to the comparatively higher affinity of heregulin to its receptor. While integrin ligation tends to be a relatively low-affinity interaction [9,58], the pentamerization of the PB [9] enhances binding by avidity, and facilitates the formation of pseudocapsids [59] that may contribute to payload protection from serum nucleases as observed here.

Conclusion

The targeted particle tested here avoids peripheral tissue damage while enabling lower drug dose for tumor killing, presenting both therapeutic and safety advantages over the untargeted drug. Delivery of a long-established, US FDA-approved chemotherapeutic may assist progress towards clinical trials. The lack of covalent modification while retaining stability allows Dox potency to remain unaltered during assembly, transport and release into target cells, thus presenting an advantage over chemical conjugates. The HER2+ cell targeting shown here avoids the cardiotoxicity associated with anthracyclines and HER2-targeted antibodies, and may provide an alternative treatment for HER2+ tumors that have accumulated signal-pathway mutations and are therefore nonresponsive to signal-blocking antibodies. Retargeting via ligand replacement has the potential to target other tumors. Altogether, these studies provide the groundwork for building an optimized tumor-targeted particle that may be expanded into the facile combination of different types of DNA-binding drugs with carrier molecules similar to HerPBK10, but designed to target different types of cancers.

Supplementary Material

Executive summary.

Particle assembly facilitates serum stability

Both electrophilic and intercalation interactions that mediate HerPBK10 and doxorubicin (Dox) self-assembly into approximately 10-nm diameter round nanoparticles also independently facilitate its serum stability.

HerDox toxicity in vitro is targeted to HER2+ cells & correlates with HER2 subunit levels

HerDox exhibits receptor-dependent cell targeting and uptake in several different human HER2+ tumor cells, including breast cancer, cervical carcinoma and glioma cells, and specifically ablates HER2+ cells in a heterogeneous cell culture.

Dox is released after cell uptake

Dox is released from the nanoparticle intracellularly by a nuclease-independent mechanism and accumulates in nucleoli whereas the untargeted drug remains throughout the nucleus, suggesting that the nucleic acid in HerDox influences the final destination of the drug.

HerDox targets HER2+ tumor cells in vivo

Systemic delivery of HerDox in a preclinical model results in tumor-preferential delivery in comparison with the untargeted drug, which exhibits higher delivery to off-target tissue.

In vivo tumor targeting is concomitant with receptor level and exhibits considerable tumor retention by 24 h after delivery compared with untargeted Dox.

HerDox elicits tumor-targeted growth ablation, while sparing off-target tissue

HerDox ablates tumors at a dose over ten-times lower than untargeted doxorubicin, while sparing the heart after intravenous delivery.

Hearts of HerDox-treated mice show no cardiac dysfunction or histological damage in contrast to the myocardial damage induced by the untargeted drug.

Livers of HerDox-treated mice showed negligible apoptosis in contrast to livers from Dox-treated mice.

Conclusion

The targeted particle tested here avoids peripheral tissue damage while enabling lower drug dose for tumor killing, presenting both therapeutic and safety advantages over the untargeted drug.

The lack of covalent modification while retaining stability allows doxorubicin potency to remain unaltered during assembly, transport and release into target cells, thus presenting an advantage over chemical conjugates.

The HER2+ cell targeting shown here avoids the cardiotoxicity associated with anthracyclines and HER2-targeted antibodies.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kolja Wawrowsky for assistance with in vitro microscopy, and NanoImaging Services, Inc. (La Jolla, CA, USA) for cryo-electron microscopy. LK Medina-Kauwe thanks JC King, M Medina-Kauwe and D Revetto for ongoing support.

Footnotes

Ethical conduct of research

The authors state that they have obtained appropriate institutional review board approval or have followed the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki for all human or animal experimental investigations. In addition, for investigations involving human subjects, informed consent has been obtained from the participants involved.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

This work was supported by grants to LK Medina-Kauwe from the NIH (R 21CA116014, R01CA102126, R01C A129822, and R01C A140995), the DoD (BC050662), the Susan G Komen Breast Cancer foundation (BCTR0201194), and the Donna and Jesse Garber Award. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

▪ of interest

▪▪ of considerable interest

- 1.Curigliano G, Mayer EL, Burstein HJ, Winer EP, Goldhirsch A. Cardiac toxicity from systemic cancer therapy: a comprehensive review. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2010;53(2):94–104. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hurley LH. DNA and its associated processes as targets for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:188–200. doi: 10.1038/nrc749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lukyanov AN, Elbayoumi TA, Chakilam AR, Torchilin VP. Tumor-targeted liposomes: doxorubicin-loaded long-circulating liposomes modified with anti-cancer antibody. J Control Release. 2004;100(1):135–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoo HS, Park TG. Folate-receptor-targeted delivery of doxorubicin nano-aggregates stabilized by doxorubicin-PEG-folate conjugate. J Control Release. 2004;100(2):247–256. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glockshuber R, Malia M, Pfitzinger I, Pluckthun A. A comparison of strategies to stabilize immunoglobulin Fv-fragments. Biochemistry. 1990;29(6):1362–1367. doi: 10.1021/bi00458a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmidt M, Maurer-Gebhard M, Groner B, Kohler G, Brochmann-Santos G, Wels W. Suppression of metastasis formation by a recombinant single chain antibody-toxin targeted to full-length and oncogenic variant EGF receptors. Oncogene. 1999;18(9):1711–1721. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goren D, Horowitz AT, Zalipsky S, Woodle MC, Yarden Y, Gabizon A. Targeting of stealth liposomes to erbB-2 (Her/2) receptor: in vitro and in vivo studies. Br J Cancer. 1996;74(11):1749–1756. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu Z, Ballinger JR, Rauth AM, Bendayan R, Wu XY. Delivery of an anticancer drug and a chemosensitizer to murine breast sarcoma by intratumoral injection of sulfopropyl dextran microspheres. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2003;55(8):1063–1073. doi: 10.1211/0022357021567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9▪▪.Medina-Kauwe LK, Kasahara N, Kedes L. 3PO, a novel non-viral gene delivery system using engineered Ad5 penton proteins. Gene Ther. 2001;8:795–803. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301448. First description of the HerPBK10 carrier protein for tumor targeting. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Medina-Kauwe LK, Maguire M, Kasahara N, Kedes L. Non-viral gene delivery to human breast cancer cells by targeted Ad5 penton proteins. Gene Ther. 2001;8:1753–1761. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11▪.Agadjanian H, Ma J, Rentsendorj A, et al. Tumor detection and elimination by a targeted gallium corrole. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(15):6105–6110. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901531106. Shows that HerPBK10 is nonimmunogenic. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12▪.Sliwkowski MX, Schaefer G, Akita RW, et al. Coexpression of erbB2 and erbB3 proteins reconstitutes a high affinity receptor for heregulin. J Biol Chem. 1994;269(20):14661–14665. One of the earliest reports indicating heregulin binds a heterodimer. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldman R, Levy RB, Peles E, Yarden Y. Heterodimerization of the erbB-1 and erbB-2 receptors in human breast carcinoma cells: a mechanism for receptor transregulation. Biochemistry. 1990;29(50):11024–11028. doi: 10.1021/bi00502a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jeschke M, Wels W, Dengler W, Imber R, Stocklin E, Groner B. Targeted inhibition of tumor-cell growth by recombinant heregulin-toxin fusion proteins. Int J Cancer. 1995;60(5):730–739. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910600527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Der Horst EH, Weber I, Ullrich A. Tyrosine phosphorylation of PYK2 mediates heregulin-induced glioma invasion: novel heregulin/HER3-stimulated signaling pathway in glioma. Int J Cancer. 2005;113(5):689–698. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewis GD, Lofgren JA, McMurtrey AE, et al. Growth regulation of human breast and ovarian tumor cells by heregulin: evidence for the requirement of ErbB2 as a critical component in mediating heregulin responsiveness. Cancer Res. 1996;56(6):1457–1465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gregory Cw, Whang Ye, Mccall W, et al. Heregulin-induced activation of HER2 and HER3 increases androgen receptor transactivation and CWR-R1 human recurrent prostate cancer cell growth. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(5):1704–1712. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18▪▪.Slamon DJ, Clark GM, Wong SG, Levin WJ, Ullrich A, Mcguire Wl. Human breast cancer: correlation of relapse and survival with amplification of the HER-2/neu oncogene. Science. 1987;235(4785):177–182. doi: 10.1126/science.3798106. One of the earliest studies correlating HER2 amplification with breast cancer aggressiveness and recalcitrance to therapy. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Slamon DJ, Clark GM. Amplification of c-erbB-2 and aggressive human breast tumors? Science. 1988;240(4860):1795–1798. doi: 10.1126/science.3289120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baselga J, Tripathy D, Mendelsohn J, et al. Phase II study of weekly intravenous recombinant humanized anti-p185HER2 monoclonal antibody in patients with HER2/neu-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:737–744. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.3.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cobleigh MA, Vogel CL, Tripathy D, et al. Efficacy and safety of herceptin (humanized anti-HER2 antibody) as a single agent in 222 women with HER2 overexpression who relapsed following chemotherapy for metastatic breast cancer. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 1998;17:97a. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vogel CL, Cobleigh MA, Tripathy D, et al. Efficacy and safety of trastuzumab as a single agent in first-line treatment of HER2-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(3):719–726. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.3.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kute T, Lack CM, Willingham M, et al. Development of Herceptin resistance in breast cancer cells. Cytometry A. 2004;57(2):86–93. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.10095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24▪▪.Crone SA, Zhao YY, Fan L, et al. ErbB2 is essential in the prevention of dilated cardiomyopathy. Nat Med. 2002;8(5):459–465. doi: 10.1038/nm0502-459. Among the earliest studies demonstrating a critical role of ErbB2 in heart maintenance. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Slamon DJ, Leyland-Jones B, Shak S, et al. Use of chemotherapy plus a monoclonal antibody against HER2 for metastatic breast cancer that overexpresses HER2. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(11):783–792. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103153441101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Medina-Kauwe LK, Leung V, Wu L, Kedes L. Assessing the binding and endocytosis activity of cellular receptors using GFP-ligand fusions. BioTechniques. 2000;29:602–609. doi: 10.2144/00293rr03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Medina-Kauwe LK. Non-viral mediated gene delivery for therapeutic applications. In: Lowenstein P, Castro M, editors. Gene Therapy for Neurological Disorders. Taylor and Francis Group LLC; London UK: 2006. pp. 115–140. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Medina-Kauwe LK, Xie J, Hamm-Alvarez S. Intracellular trafficking of nonviral vectors. Gene Ther. 2005;12(24):1734–1751. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rentsendorj A, Agadjanian H, Ma J, et al. New approach for targeting RNAi-mediated toxicity to cancer cells. Presented at: The American Society of Gene Therapy Annual Meeting; MA USA. 28 May– 1 June; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rentsendorj A, Xie J, Macveigh M, et al. Typical and atypical trafficking pathways of Ad5 penton base recombinant protein: implications for gene transfer. Gene Ther. 2006;13(10):821–836. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meyer M, Dohmen C, Philipp A, et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of a bioresponsive and endosomolytic siRNA-polymer conjugate. Mol Pharm. 2009;6(3):752–762. doi: 10.1021/mp9000124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li SD, Chen YC, Hackett MJ, Huang L. Tumor-targeted delivery of siRNA by self-assembled nanoparticles. Mol Ther. 2008;16(1):163–169. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Christgen M, Lehmann U. MDA-MB-435: the questionable use of a melanoma cell line as a model for human breast cancer is ongoing. Cancer Biol Ther. 2007;6(9):1355–1357. doi: 10.4161/cbt.6.9.4624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chambers AF. MDA-MB-435 and M14 cell lines: identical but not M14 melanoma? Cancer Res. 2009;69(13):5292–5293. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hwang JY, Wachsmann-Hogiu S, Ramanujan VK, et al. Multimodal wide-field two-photon excitation imaging: characterization of the technique for in vivo applications. Biomed Opt Express. 2011;2(2):356–364. doi: 10.1364/BOE.2.000356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hwang JY, Wachsmann-Hogiu S, Ramanujan VK, et al. Multimode optical imaging system for preclinical applications in vivo: technology development, multiscale imaging, and chemotherapy assessment. Mol Imaging Biol. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s11307-011-0517-z. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hwang Jy, Moffatt-Blue C, Equils O, et al. Multimode optical imaging of small animals: development and applications. Proc SPIE. 2007;6441:644105. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mohan P, Rapoport N. doxorubicin as a molecular nanotheranostic agent: effect of doxorubicin encapsulation in micelles or nanoemulsions on the ultrasound-mediated intracellular delivery and nuclear trafficking. Mol Pharm. 2010;7(6):1959–1973. doi: 10.1021/mp100269f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Karimi G, Ramezani M, Abdi A. Protective effects of lycopene and tomato extract against doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Phytother Res. 2005;19(10):912–914. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shuai Y, Guo JB, Peng SQ, et al. Metallothionein protects against doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy through inhibition of superoxide generation and related nitrosative impairment. Toxicol Lett. 2007;170(1):66–74. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2007.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lis R, Capdet J, Mirshahi P, et al. Oncologic trogocytosis with hospicells induces the expression of N-cadherin by breast cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 2010;37(6):1453–1461. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shinohara ET, Maity A. Increasing sensitivity to radiotherapy and chemotherapy by using novel biological agents that alter the tumor microenvironment. Curr Mol Med. 2009;9(9):1034–1045. doi: 10.2174/156652409789839107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murakami M, Cabral H, Matsumoto Y, et al. Improving drug potency and efficacy by nanocarrier-mediated subcellular targeting. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3(64):64ra62. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oh K, Baik H, Lee A, et al. The reversal of drug-resistance in tumors using a drug-carrying nanoparticular system. Int J Mol Sci. 2009;10(9):3776–3792. doi: 10.3390/ijms10093776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lechardeur D, Sohn KJ, Haardt M, et al. Metabolic instability of plasmid DNA in the cytosol: a potential barrier to gene transfer. Gene Ther. 1999;6(4):482–497. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pollard H, Toumaniantz G, Amos JL, et al. Ca2+-sensitive cytosolic nucleases prevent efficient delivery to the nucleus of injected plasmids. J Gene Med. 2001;3(2):153–164. doi: 10.1002/jgm.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47▪.Zelphati O, Szoka FC. Mechanism of oligonucleotide release from cationic liposomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93(21):11493–11498. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11493. Presents the mechanism of oligonucleotide release from endosomes into the cytosol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Samarsky DA, Fournier MJ, Singer RH, Bertrand E. The snoRNA box C/D motif directs nucleolar targeting and also couples snoRNA synthesis and localization. EMBO J. 1998;17(13):3747–3757. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.13.3747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lange TS, Borovjagin AV, Gerbi SA. Nucleolar localization elements in U8 snoRNA differ from sequences required for rRNA processing. RNA. 1998;4(07):789–800. doi: 10.1017/s1355838298980438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Curnis F, Sacchi A, Corti A. Improving chemotherapeutic drug penetration in tumors by vascular targeting and barrier alteration. J Clin Invest. 2002;110(4):475–482. doi: 10.1172/JCI15223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kukowska-Latallo JF, Candido KA, Cao Z, et al. Nanoparticle targeting of anticancer drug improves therapeutic response in animal model of human epithelial cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65(12):5317–5324. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Maeda H. Tumor-selective delivery of macromolecular drugs via the EPR effect: background and future prospects. Bioconjug Chem. 2010;21(5):797–802. doi: 10.1021/bc100070g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Medina-Kauwe Lk, Chen X. Vitamins and Hormones. Elsevier Science; CA, USA: 2002. Using GFP-ligand fusions to measure receptor-mediated endocytosis in living cells; pp. 81–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Agadjanian H, Weaver JJ, Mahammed A, et al. Specific delivery of corroles to cells via noncovalent conjugates with viral proteins. Pharm Res. 2006;23(2):367–377. doi: 10.1007/s11095-005-9225-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Park JW, Hong K, Kirpotin DB, et al. Anti-HER2 immunoliposomes: enhanced efficacy attributable to targeted delivery. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8(4):1172–1181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Drummond DC, Meyer O, Hong K, Kirpotin DB, Papahadjopoulos D. Optimizing liposomes for delivery of chemotherapeutic agents to solid tumors. Pharmacol Rev. 1999;51(4):691–743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Minotti G, Menna P, Salvatorelli E, Cairo G, Gianni L. Anthracyclines: molecular advances and pharmacologic developments in antitumor activity and cardiotoxicity. Pharmacol Rev. 2004;56(2):185–229. doi: 10.1124/pr.56.2.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wickham TJ, Mathias P, Cheresh DA, Nemerow GR. Integrins and αvβ3 αvβ5 promote adenovirus internalization but not virus attachment. Cell. 1993;73(2):309–319. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90231-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fender P, Schoehn G, Foucaud-Gamen J, et al. Adenovirus dodecahedron allows large multimeric protein transduction in human cells. J Virol. 2003;77(8):4960–4964. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.8.4960-4964.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Website

- 101.Demonstration of daily tail vein injections. www.youtube.com/watch?v=zbqjZ2HL_-0.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.