Abstract

Escherichia coli possesses a number of proteins that transport sugars out of the cell. We identified 31 candidate sugar efflux transporters based on their similarity to known sugar efflux transporters. We then tested whether these transporters affect arabinose and xylose metabolism. We identified 13 transporters – setC, cmr, ynfM, mdtD, yfcJ, yhhS, emrD, ydhC, ydeA, ybdA, ydeE, mhpT, and kgtP – that appeared to increase or decrease intracellular arabinose concentrations when respectively deleted or over-expressed. None of the candidate transporters affected xylose concentrations. These results indicate that E. coli possesses multiple arabinose efflux transporters. They also provide a novel target for future metabolic engineering.

Introduction

Escherichia coli expresses proteins that not only transport sugars into cells but also a number of proteins that transport them out of the cell. The canonical example is the SET family of transporters: SetA, SetB, and SetC [1], [2]. These transporters have been previously shown to actively efflux glucose and lactose from cells. In addition, they have broad specificity for various glucosides or galactosides. Aside from the SET family, YdeA has also been shown to efflux L-arabinose from cells [3], [4].

Efflux transporters have been extensively studied in the literature in the context of multi-drug resistance (MDR). Little is known about these sugar efflux transporters, or what roles they may play in cellular metabolism. One possible mechanism is to relieve sugar-phosphate stress. Sun and Vanderpool demonstrated that SetA participates in the glucose-phosphate stress response [5]. However, they found that SetA does not efflux alpha-methylglucoside, the nonmetabolizable sugar analog used to elicit the response. Another proposal is that they function as safety valves, preventing excess sugar from accumulating within the cell [6]. However, this hypothesis has yet to be tested.

In this work, we investigated L-arabinose and D-xylose (hereafter referred to simply as arabinose and xylose, respectively) efflux in E. coli. Sequence analysis identified 31 candidate sugar efflux transporters in E. coli based on homology to known sugar efflux transporters. Using genetic approaches, we tested whether these candidate efflux transporters target arabinose and xylose. We were able to identify multiple putative arabinose efflux transporters but interestingly none for xylose.

Results

Effect of Deleting Candidate Sugar Efflux Transporters on Arabinose Metabolism

We identified 31 candidate sugar efflux transporters in E. coli based on homology to the known sugar efflux transporters: ydeA, setA, and setB ( Table 1 ). We identified these homologs based on their membership in the same Cluster of Orthologous Group of proteins, COG2814 [7], [8]. These homologs included a number of multidrug efflux transporters, both known and putative, along with five transporters involved in the uptake of various metabolites (shiA, kgtP, galP, nanT, and proP).

Table 1. List of genes.

| Gene | Annotation |

| setA | broad specificity sugar efflux system |

| setB | lactose/glucose efflux system |

| setC | predicted sugar efflux system |

| ydeA | sugar efflux transporter |

| mhpT | putative 3-hydroxyphenylpropionic acid transporter |

| yajR | putative transporter |

| ybdA (entS) | predicted transporter |

| cmr (mdfA) | multidrug efflux system protein |

| ycaD | putative MFS family transporter |

| yceL | orf, hypothetical protein |

| ydeE | predicted transporter |

| ynfM | predicted transporter |

| ydhP | predicted transporter |

| mdtG (yceE) | predicted drug efflux system |

| yebQ | putative transporter |

| shiA | shikimate transporter |

| mdtD (yegB) | multidrug efflux system protein |

| bcr | bicyclomycin/multidrug efflux system |

| yfcJ | predicted transporter |

| kgtP | alpha-ketoglutarate transporter |

| ygcS | putative transporter |

| galP | D-galactose transporter |

| nanT | sialic acid transporter |

| yhhS | putative transporter |

| nepI (yicM) | predicted transporter |

| emrD | 2-module integral membrane pump; multidrug resistance |

| mdtL (yidY) | multidrug efflux system protein |

| proP | proline/glycine betaine transporter |

| yjhB | putative transporter |

| yjiO (mdtM) | multidrug efflux system protein |

| ydhC | predicted transporter |

If any of these genes encodes an efflux transporter of arabinose, then deleting the gene should increase the intracellular sugar concentration of arabinose. As an indirect measure of intracellular arabinose concentrations, we employed transcriptional fusions of araBAD promoter to Venus, a fast-folding variant of the yellow fluorescent protein [9]. The average activity of the araBAD promoter as determined using fluorescence is proportional to extracellular arabinose concentrations and presumably relative intracellular arabinose concentrations as well based on the known mechanism for regulation [10]. To test the effect of deleting these genes, we grew the cells in tryptone broth at varying concentrations of arabinose and then harvested the cells at late-exponential phase to determine relative araBAD promoter activities. The resulting data were fit to a Michaelis-Menten dose-response curve with the governing parameters, Vmax and Km, reported ( Table 2 ).

Table 2. KM and Vmax values* determined from deletion and overexpression studies.

| Gene | KM | Vmax | Gene | 2 mMIPTG | 0.2 mMIPTG | |||

| KM | Vmax | KM | Vmax | |||||

| Control | 3.17 ± 1.25 | 6.88 ± 1.01 | Control | 2.73 ± 1.01 | 11.1 ± 1.01 | 2.84 ± 1.30 | 11.9 ± 1.92 | |

| setC | 3.51 ± 0.96 | 12.7 ± 1.37 | setC | Growth defect | 5.27 ± 3.86 | 6.49 ± 2.22 | ||

| cmr | 3.94 ± 1.36 | 13.2 ± 1.88 | ydeE | Growth defect | 4.10 ± 0.93 | 7.59 ± 0.72 | ||

| ynfM | 3.77 ± 0.96 | 12.3 ± 1.28 | ydeA | 3.11 ± 1.09 | 4.53 ± 0.59 | No effect | ||

| mdtD | 4.17 ± 1.56 | 13.8 ± 2.18 | kgtP | 2.75 ± 2.67 | 7.65 ± 2.60 | No effect | ||

| yfcJ | 3.04 ± 1.95 | 9.96 ± 2.34 | mhpT | 0.34 ± 0.17 | 7.08 ± 0.36 | 1.35 ± 0.71 | 7.47 ± 0.97 | |

| yhhS | 4.96 ± 1.97 | 14.8 ± 2.67 | ybdA | 0.93 ± 0.35 | 6.84 ± 0.52 | 1.33 ± 0.75 | 7.93 ± 1.08 | |

| emrD | 3.61 ± 1.48 | 12.6 ± 2.05 | ||||||

| ydhC | 3.82 ± 1.61 | 12.4 ± 2.12 | ||||||

KM values are reported in mM. Vmax values are reported as Fluorescence/OD600. Errorbars provide 95% confidence intervals on the parameter estimates.

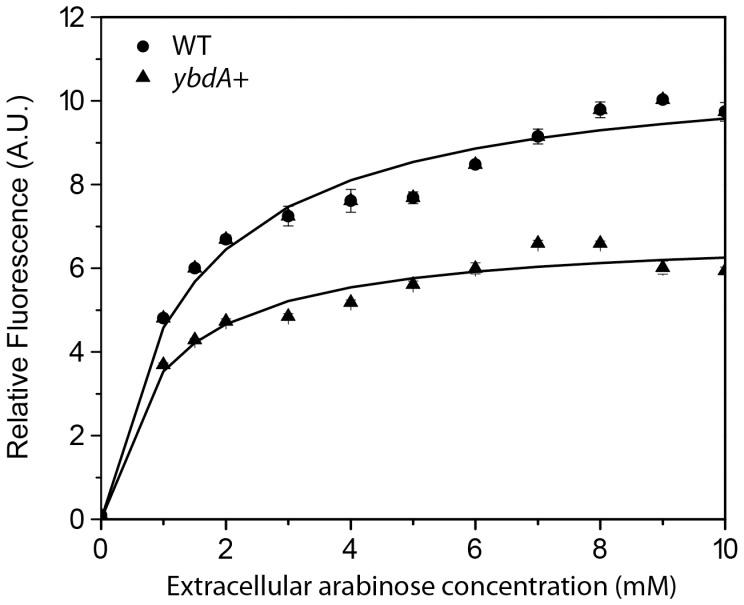

Deletion of the following eight genes was found to increase intracellular arabinose concentrations as compared to the wild-type control: setC, cmr, ynfM, mdtD, yfcJ, yhhS, emrD and ydhC. Deleting the other genes had no effect, with the dose-response curves indistinguishable from the wild-type control. Our specific metric was a statistically significant difference in the calculated Vmax values. A representative dose-response curve for the Δcmr mutant is shown in Figure 1 . These results suggest that these eight genes encode arabinose efflux transporters. Among them, only SetC has previously been implicated in sugar efflux based on its homology to SetA and SetB, two transporters known to efflux lactose [2]. Cmr, also known as MdfA, and EmrD are known multidrug efflux transporters [11], [12], [13]. Over-expression of Cmr has also been shown to limit the uptake of isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), an effect attributed to efflux [14]. YnfM, MdtD, YfcJ, and YdhC are uncharacterized major facilitator superfamily (MFS) transporters. YhhS is also an uncharacterized MFS transporter that has been implicated glyphosate resistance [15].

Figure 1. Dose-response curve for the Δcmr mutant.

ParaB-venus in WT and Δcmr mutant strains were measured for fluorescence and the results are reported as Fluorescence/OD600. Strains were induced with arabinose concentrations varying from 0 mM to 10 mM.

Interestingly, we did not observe any change in a ΔydeA mutant, though we did observe an effect when overexpressing ydeA as discussed below. This gene is known to encode an arabinose efflux transporter [3], [4], and Carolé and coworkers have previously shown that disrupting the ydeA gene increases intracellular arabinose concentrations. The lack of agreement between their results and ours may be due to the fact that they employed a strain lacking the arabinose metabolic genes, which dramatically increases intracellular arabinose concentrations as shown below, whereas we employed wild-type MG1655.

Effect of Over-expressing Candidate Sugar Efflux Transporters on Arabinose Metabolism

We also over-expressed these candidate sugar efflux transporters. If these genes encode arabinose efflux transporters, then over-expressing them should reduce intracellular arabinose concentrations. To express these genes, they were cloned on high-copy plasmids under the control of the strong, IPTG-inducible trc promoter. Once again, transcriptional fusions to the araBAD promoter were employed as indirect measures of intracellular arabinose and the results were recorded in terms of the governing parameters for a Michaelis-Menten dose-response curve ( Table 2 ).

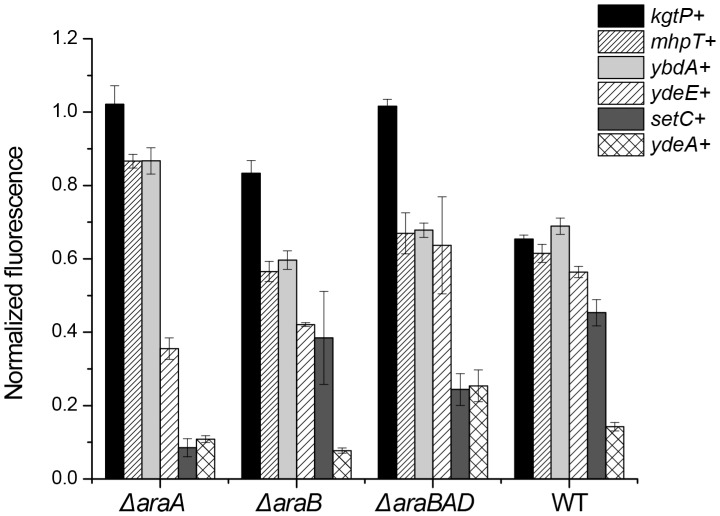

Over-expression of six genes were found to reduce intracellular arabinose concentrations: setC, ydeA, ybdA, ydeE, mhpT, and kgtP. A representative dose-response curve for ybdA is given in Figure 2 . Among the six, only setC and ydeA have been implicated in sugar efflux as discussed above. YbdA, also known as EntS, has been implicated in enterobacterin transport [16] and is involved in the resistance to multiple chemical stresses [17]. YdeE is an uncharacterized MFS transporter involved in dipeptide transport and resistance [18]. MhpT is a putative 3-hydroxyphenylpropionic acid transporter. KgtP, interestingly, is known to be α ketoglutarate transporter [19].

Figure 2. Dose-response curve for ybdA overexpression.

ParaB-venus in WT and ybdA overexpressing strains were measured for fluorescence and the results are reported as Fluorescence/OD600. Strains were induced with arabinose concentrations varying from 0 mM to 10 mM. The ybdA overexpressing strain was induced with 2 mM IPTG.

When comparing these results with our deletion results, only setC gave a consistent result where loss of the gene increases intracellular arabinose and overexpression decreases it. Over-expression of yfcJ, yhhS, emrD, and ydhC had no effect on intracellular arabinose concentrations. Three genes that gave a deletion phenotype were toxic to the cell when over-expressed: cmr, ynfM, and mdtD.

Overall, 12 genes were toxic to E. coli when over-expressed: setB, setC, yajR, cmr, ycaD, ydeE, ynfM, mdtD, bcr, ygcS, yjhB, and yjiO. To limit toxicity, the over-expression experiments were performed at two concentrations of the IPTG inducer. However, six genes were still toxic when induced even at lower concentrations of IPTG: ycaD, ynfM, mdtD, bcr, and ygcS, and yjhB. Both setC and ydeE were toxic to the cell when expressed using the higher IPTG concentration; only at the lower concentration did we observe an effect. Conversely, we only observed an effect with ydeA and kgtP when they were induced at higher IPTG concentration. Both ybdA and mphT decrease intracellular arabinose concentrations at both induction levels.

Xylose is Not a Target for Any of the Candidate Efflux Transporters

We also tested whether any of these candidate efflux transporters target xylose. A similar approach was employed as before except that we used transcriptional fusions of the xylA promoter to Venus. The xylA promoter is positively regulated by XylR in response to xylose [20] and can equivalently be used to determine relative intracellular xylose concentration. Otherwise, the experiments were performed in an identical manner to the arabinose experiments. Despite the similarities between xylose and arabinose, we did not observe any change in intracellular xylose concentrations as compared to the wild-type control when any of candidate genes were deleted or overexpressed.

Arabinose is a Substrate for Most Efflux Transporters

The arabinose metabolic intermediate, L-ribulose-5-phosphate, is toxic to E. coli [21]. This may provide one possible explanation as to why arabinose may be effluxed from cells. It also suggests that arabinose itself may not be the target for efflux but rather an intermediate of arabinose metabolism. To test this hypothesis, we blocked different steps in arabinose metabolism by deleting the cognate gene and then determined how the mutation would affect our results concerning arabinose efflux. If arabinose is not the target for these transporters and the downstream metabolite is instead, then we expect that blocking metabolism will reduce the effect of these transporters. Briefly, the arabinose metabolic pathway involves three steps: 1) isomerization to L-ribulose (araA); 2) phosphorylation to L-ribulose-5-phosphate (araB); and 3) inversion to D-xylulose-5-phosphate (araD). We tested three mutants: ΔaraA, ΔaraB, and ΔaraBAD. We did not test a ΔaraD mutant as arabinose is toxic in this strain.

Blocking any step in arabinose metabolism significantly increased the concentration of intracellular arabinose relative to the wild-type control. This is expected, as arabinose is no longer being metabolized in any of these strains. However, we did not observe any further increase when setC, mhpT, cmr, ynfM, mdtD, yfcJ, yhhS, and emrD were deleted as well (data not shown). These results suggest that arabinose concentrations are already high in these cells and eliminating efflux does not further increase arabinose concentration. Therefore, we were unable to conclude anything from these deletion experiments.

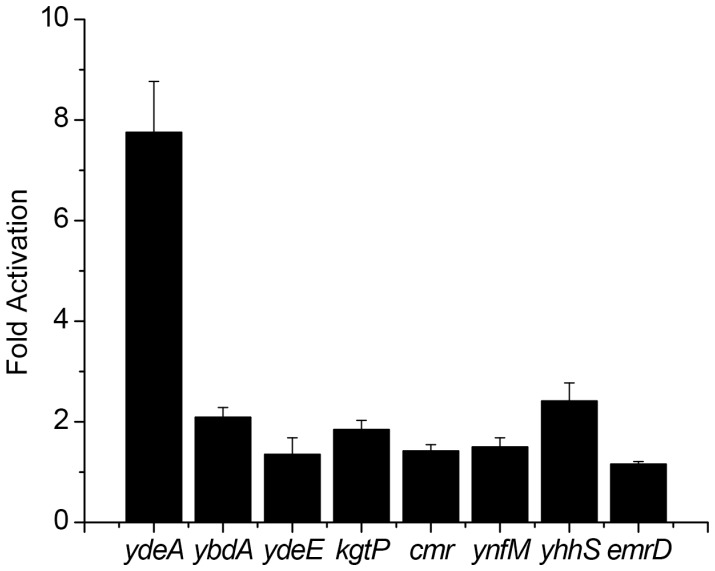

The effect of overexpressing of setC, ydeE, and ydeA was most pronounced in a ΔaraA mutant, indicating that the three target arabinose ( Figure 3 ). If they targeted a downstream metabolite, then we would not expect a reduction in intracellular arabinose concentrations. The data for mhpT and ybdA were more equivocal though again they suggest that these transporters both target arabinose. Interestingly, we only observed a reduction in relative arabinose concentrations only when kgtP was overexpressed in a ΔaraB mutant or the wild type. These results suggest that L-ribulose may be the target for KgtP as we did not observe a reduction relative to the wild-type control in a ΔaraA mutant where the downstream metabolites are not produced. Note, the results in Figure 3 are normalized relative to the wild-type control.

Figure 3. Overexpression of the efflux transporters in arabinose metabolic mutants.

The data is normalized to the relative fluorescence values of the control strains (ParaB-venus and pTrC99A in each of the individual arabinose mutants). All of the strains were induced with 5 mM arabinose. Overexpression of the the efflux transporters was induced with 2 mM IPTG except for the overexpression of setC and ydeE where 0.2 mM IPTG was used.

Expression of Efflux Transporters is Induced by Arabinose

The last question explored was whether arabinose induced the expression of these transporters. To answer this question, we fused the promoters for these transporters to Venus and then tested whether they were activated by arabinose. Of the 13 transporters, we were able to construct functional promoter fusions to all but five. Our transcriptional fusions to the mhpT, mdtD, and yfcJ promoters were not functional despite repeated attempts. In addition, the fusions to the setC and ydhC promoters were very weak and not included in our results as a consequence.

Of the eight remaining functional promoters, only the ydeA and yhhS promoters were activated at significant levels ( Figure 4 ). The remaining six promoters were also activated by arabinose though the effect is less than two fold. How these promoters, in particular for the ydeA and yhhS genes, are being activated by arabinose is not known. Interesting, ydeA is strongly induced by arabinose yet deleting this gene does not affect intracellular arabinose concentrations – only when over-expressed do we observe an effect.

Figure 4. Efflux promoter transcriptional fusions.

Reporters are in a wild-type background and the data are normalized to the relative fluorescence values when no arabinose is added. All of the strains were induced with 10 mM arabinose.

Discussion

We identified multiple candidate sugar efflux transporters in E. coli based on sequence homology to known sugar efflux transporters and then tested to see whether they target arabinose and xylose. Thirteen putative arabinose efflux transporters were identified based on their ability to alter intracellular arabinose concentration. Eight were found to increase intracellular arabinose concentrations when deleted and six to decrease concentrations when overexpressed. Only one transporter, SetC, was found to yield reciprocal results when deleted or overexpressed. Among the 13 putative transporters, only YdeA has previously been shown to be an arabinose efflux transporter. Interestingly, none affected intracellular xylose concentrations.

We cannot definitely say whether these putative transporters in fact efflux arabinose as we did not directly measure arabinose transport. All that we can say with certainty is that these 13 transporters inhibit the accumulation of arabinose with efflux being the likely but not sole possible mechanism. Alternate mechanisms include the inhibition of the arabinose uptake and the efflux of other compounds that affect arabinose metabolism or possibly stimulate other efflux transporters.

Many efflux transporters are TolC dependent [22]. Martin and Rosner previously found that the mar/sox/rob regulon was activated in a tolC mutant [23]. They proposed that this activation is due to the accumulation of intracellular metabolites due to the loss of efflux. We also tested whether any of the identified arabinose efflux transporters were TolC dependent. While we observed that intracellular arabinose concentrations were higher in a tolC mutant, we were unable to determine whether any of these efflux transporters were TolC dependent as our data were equivocal (results not shown). Aside from TolC, these candidate efflux transporters may associate with other proteins that were not considered in our analysis. If this is the case, then the over-expression studies may have missed some efflux transporters as the accessory proteins would not be expressed in the correct stoichiometry for these over-expressed transporters to be functional.

A number of the identified efflux transporters have previously been shown to transport other compounds both in and out of the cell. Cmr, for example, is known to efflux a number of chemically unrelated compounds [11], so it is not entirely implausible that it effluxes arabinose as well. This is consistent with multidrug efflux transporters in general, which are known to have broad substrate specificities. What is surprising is that transporters such as KgtP, a known α ketoglutarate transporter [19], also inhibit arabinose uptake and perhaps efflux it as well. Clearly further research is required to identify the exact mechanisms for how these transporters affect arabinose uptake and efflux.

Why would E. coli want to efflux arabinose from the cell? One possibility is to limit the accumulation of toxic sugar phosphates, such as the arabinose metabolic intermediate L-ribulose-5-phosphate, within the cell. If the flux of arabinose is greater than the pentose phosphate pathway can accommodate, then L-ribulose-5-phosphate may accumulate within the cell due to an effective roadblock within the pathway. Under such a scenario, arabinose efflux transporters would provide a relief valve for the cell. A second possibility is to limit the accumulation of methylglyoxal, another toxic compound to E. coli [24]. Methylglyoxal synthase is thought to provide a relief valve in glycolysis, preventing the buildup of dihydroxyacetone phosphate when inorganic phosphate is limiting. If the flux of arabinose is too high, it may overwhelm the glycolytic branch of the pathway leading to a buildup of dihydroxyacetone phosphate. Consistent with this model, the addition of cAMP to cells grown on arabinose or xylose, which increases the uptake of these two sugars, produce excess methylglyoxal, arresting cell growth [25]. Interestingly, the effect is less severe with arabinose, consistent with our result showing a lack of xylose efflux transporters. In addition, the overexpression of methylglyoxal synthase is lethal to cells grown on arabinose and xylose but not on glucose. Unlike arabinose and xylose dissimilation, glycolysis is linked to glucose transport through the phosphenolpyruvate transferase system [26]. In the case of arabinose and xylose dissimilation, transport and metabolism are uncoupled. Arabinose efflux may provide a relief valve to accommodate this uncoupling. Why there are not similar relief valves for xylose is not known, though it may be that xylose efflux transporters do in fact exist but were not among the 31 analyzed.

Other outstanding questions concern the regulation of these transporters. Arabinose was found to induce the expression of many efflux transporters, where the effects were most pronounced for the YdeA and YhhS transporters. We and others have previously speculated that the multidrug antibiotic resistance (MDR) mechanisms in bacteria evolved in part as a mechanism to prevent the buildup of toxic metabolites [23], [27]. In fact, we found that 2,3-dihydroxybenzoate, an intermediate in enterobactin biosynthesis, directly binds to and inactivates MarR, the key regulator of the marRAB operon involved in antibiotic resistance. Whether arabinose and other sugars activate the MDR regulators is not known though it is an intriguing hypothesis nonetheless.

We conclude by noting that sugar efflux may provide a novel target for metabolic engineering. In particular, one may be able to increase the metabolic flux through a given pathway by eliminating the efflux of the governing sugar. The present work was motivated in part by looking at novel targets for optimizing pentose metabolism in E. coli. Of course, naively removing these transporters may have a detrimental effect on the cell due to the buildup of toxic metabolites. Any design targeting efflux may also need to make commensurate changes to transport and metabolism. Whether sugar efflux transporters provide a viable target for metabolic engineering is not known, but it does provide a totally unexplored area that clearly merits further investigation.

Materials and Methods

Media and Growth Conditions

Luria-Bertani liquid and solid medium (10 g/l tryptone, 5 g/l yeast extract, 10 g/l NaCl) was used for routine bacterial culture and genetic manipulation. All experiments were performed in tryptone broth at 37°C. Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: ampicillin at 100 µg/ml, chloramphenicol at 20 µg/ml, and kanamycin at 40 µg/ml. Inducer isopropyl-β-D-galactopyranoside (IPTG) was used at a concentration of 2 mM unless otherwise specified. All experiments involving the growth of cells carrying the helper plasmid pKD46 were performed at 30°C. Loss of pKD46 was achieved by growth at 42°C under nonselective conditions on LB agar. The removal of the antibiotic cassette from the FLP recombinant target (FRT)-chloramphenicol/kanamycin-FRT insert was obtained by the transformation of the helper plasmid pCP20 into the respective strain and selection on ampicillin at 30°C. Loss of pCP20 was obtained by growth at 42°C under nonselective conditions on LB agar. Primers were purchased from IDT, Inc. Enzymes were purchased from New England Biolabs and Fermentas.

Strain and Plasmid Construction

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are described in Tables 3 and 4 . All strains are isogenic derivatives of Escherichia coli K-12 strain MG1655. All cloning steps were performed in E. coli strain DH5α (phi-80d lacΔm15 enda1 recA1 hsdR17 supE44 thh-1 gyrA96 relAΔlacU169). Targeted gene deletions and subsequent marker removal were made using the λRed recombinase method of Datsenko and Wanner [28]. The generalized transducing phage P1vir was used in all genetic crosses according to standard methods [29].

Table 3. Bacterial strains used in this work.

| Strain | Genotype or relevant characteristicsa | Source or referenceb,c |

| MG1655 | F- λ- ilvG rph-1 | CGSC #7740 |

| DH5α | phi-80d lacΔm15 enda1 recA1 hsdR17 supE44 thh-1 gyrA96 relAΔlacU169 | New England Biolabs |

| CR400 | ΔaraA::kan | [32] |

| CR401 | ΔaraB::kan | [32] |

| CR404 | ΔaraBAD::kan | [32] |

| CR701 | ΔtolC::cat | [27] |

| CR702 | ΔtolC::FRT | [27] |

| CR1100 | ΔsetA:: FRT kan FRT (77621–78799) | |

| CR1101 | ΔsetB:: FRT kan FRT (2261885–2263066) | |

| CR1102 | ΔsetC:: FRT kan FRT (3834976–3836160) | |

| CR1103 | ΔydeA:: FRT kan FRT (1615052–1616242) | |

| CR1104 | ΔmhpT:: FRT kan FRT (374683–375894) | |

| CR1105 | ΔyajR:: FRT kan FRT (444526–445890) | |

| CR1106 | ΔybdA::FRT kan FRT (621523–622773) | |

| CR1107 | Δcmr::FRT kan FRT (882896–884128) | |

| CR1108 | ΔycaD::FRT kan FRT (945094–946242) | |

| CR1109 | ΔyceL::FRT kan FRT (1123341–1124549) | |

| CR1110 | ΔydeE::FRT kan FRT (1619356–1620543) | |

| CR1111 | ΔynfM::FRT kan FRT (1667723–1668976) | |

| CR1112 | ΔydhP::FRT kan FRT (1734145–1735314) | |

| CR1113 | ΔmdtG::FRT kan FRT (1113487–1114713) | |

| CR1114 | ΔyebQ::FRT kan FRT (1908300–1909673) | |

| CR1115 | ΔshiA::FRT kan FRT (2051667–2052983) | |

| CR1116 | ΔmdtD::FRT kan FRT (2159488–2160903) | |

| CR1117 | Δbcr::FRT kan FRT (2276592–2277782) | |

| CR1118 | ΔyfcJ::FRT kan FRT (2436964–2438142) | |

| CR1119 | ΔkgtP::FRT kan FRT (2722470–2723768) | |

| CR1120 | ΔygcS::FRT kan FRT (2894555–2895892) | |

| CR1121 | ΔgalP::FRT kan FRT (3086306–3087700) | |

| CR1122 | ΔnanT::FRT kan FRT (3369106–3370596) | |

| CR1123 | ΔyhhS::FRT kan FRT (3608539–3609756) | |

| CR1124 | ΔnepI::FRT kan FRT (3838572–3839762) | |

| CR1125 | ΔemrD::FRT kan FRT (3851945–3853129) | |

| CR1126 | ΔmdtL::FRT kan FRT (3889638–3890813) | |

| CR1127 | ΔproP::FRT kan FRT (4328525–4330027) | |

| CR1128 | ΔyjhB::FRT kan FRT (4502081–4503298) | |

| CR1129 | ΔyjiO::FRT kan FRT (4565310–4566542) | |

| CR1130 | ΔydhC::FRT kan FRT (1737935–1739146) | |

| CR1131 | ΔsetA::FRT | |

| CR1132 | ΔsetB::FRT | |

| CR1133 | ΔsetC::FRT | |

| CR1134 | ΔydeA::FRT | |

| CR1135 | ΔmhpT::FRT | |

| CR1136 | ΔyajR::FRT | |

| CR1137 | ΔybdA::FRT | |

| CR1138 | Δcmr::FRT | |

| CR1139 | ΔycaD::FRT | |

| CR1140 | ΔyceL::FRT | |

| CR1141 | ΔydeE::FRT | |

| CR1142 | ΔynfM::FRT | |

| CR1143 | ΔydhP::FRT | |

| CR1144 | ΔmdtG::FRT | |

| CR1145 | ΔyebQ::FRT | |

| CR1146 | ΔshiA::FRT | |

| CR1147 | ΔmdtD::FRT | |

| CR1148 | Δbcr::FRT | |

| CR1149 | ΔyfcJ::FRT | |

| CR1150 | ΔkgtP::FRT | |

| CR1151 | ΔygcS::FRT | |

| CR1152 | ΔgalP::FRT | |

| CR1153 | ΔnanT::FRT | |

| CR1154 | ΔyhhS::FRT | |

| CR1155 | ΔnepI::FRT | |

| CR1156 | ΔemrD::FRT | |

| CR1157 | ΔmdtL::FRT | |

| CR1158 | ΔproP::FRT | |

| CR1159 | ΔyjhB::FRT | |

| CR1160 | ΔyjiO::FRT | |

| CR1161 | ΔydhC::FRT | |

| CR1162 | ΔsetC::FRT ?araA::FRT | |

| CR1163 | Δcmr::FRT ?araA::FRT | |

| CR1164 | ΔynfM::FRT ?araA::FRT | |

| CR1165 | ΔydhP::FRT ?araA::FRT | |

| CR1166 | ΔmdtD::FRT ?araA::FRT | |

| CR1167 | ΔyfcJ::FRT ?araA::FRT | |

| CR1168 | ΔyhhS::FRT ?araA::FRT | |

| CR1169 | ΔemrD::FRT ?araA::FRT | |

| CR1170 | ΔydhC::FRT ?araA::FRT | |

| CR1171 | ΔsetC::FRT ?araB::FRT | |

| CR1172 | Δcmr::FRT ?araB::FRT | |

| CR1173 | ΔynfM::FRT ?araB::FRT | |

| CR1174 | ΔmdtD::FRT ?araB::FRT | |

| CR1175 | ΔyfcJ::FRT ?araB::FRT | |

| CR1176 | ΔyhhS::FRT ?araB::FRT | |

| CR1177 | ΔemrD::FRT ?araB::FRT | |

| CR1178 | ΔydhC::FRT ?araB::FRT | |

| CR1179 | ΔsetC::FRT ?araBAD::FRT | |

| CR1180 | Δcmr::FRT ?araBAD::FRT | |

| CR1181 | ΔynfM::FRT ?araBAD::FRT | |

| CR1182 | ΔmdtD::FRT ?araBAD::FRT | |

| CR1183 | ΔyfcJ::FRT ?araBAD::FRT | |

| CR1184 | ΔyhhS::FRT ?araBAD::FRT | |

| CR1185 | ΔemrD::FRT ?araBAD::FRT | |

| CR1186 | ΔydhC::FRT ?araBAD::FRT |

All strains are isogenic derivatives of E. coli K-12 strain MG1655.

All strains are from this work unless otherwise noted.

E. coli Genetic Stock Center, CGSC, Yale University.

Table 4. Plasmids used in this work.

| Plasmids | Genotype or relevant characteristics | Source or referencea |

| pKD46 | bla PBAD gam bet exo pSC101 ori(ts) | [28] |

| pCP20 | bla cat cI857 λPR’-flp pSC101 ori(ts) | [33] |

| pKD3 | bla FRT cm FRT oriR6K | [28] |

| pKD4 | bla FRT kan FRT oriR6K | [28] |

| pPROBE venus | kan venus ori p15a | |

| pTrC99A | amp Ptrc ori (pBR322) laclq | [31] |

| ParaB-venus | kan ParaB-venus ori p15a | |

| PxylA-venus | kan PxylA-venus ori p15a | |

| KK001 (pSetA) | amp Ptrc setA ori (pBR322) laclq | |

| KK002 (pSetB) | amp Ptrc setB ori (pBR322) laclq | |

| KK003 (pSetC) | amp Ptrc setC ori (pBR322) laclq | |

| KK004 (pYdeA) | amp Ptrc setA ori (pBR322) laclq | |

| KK005 (pMhpT) | amp Ptrc mhpT ori (pBR322) laclq | |

| KK006 (pYajR) | amp Ptrc yajR ori (pBR322) laclq | |

| KK007 (pYbdA) | amp Ptrc ybdA ori (pBR322) laclq | |

| KK008 (pCmr) | amp Ptrc cmr ori (pBR322) laclq | |

| KK009 (pYcaD) | amp Ptrc ycaD ori (pBR322) laclq | |

| KK010 (pYceL) | amp Ptrc yceL ori (pBR322) laclq | |

| KK011 (pYdeE) | amp Ptrc ydeE ori (pBR322) laclq | |

| KK012 (pYnfM) | amp Ptrc ynfM ori (pBR322) laclq | |

| KK013 (pYdhP) | amp Ptrc ydhP ori (pBR322) laclq | |

| KK014 (pMdtG) | amp Ptrc mdtG ori (pBR322) laclq | |

| KK015 (pYebQ) | amp Ptrc yebQ ori (pBR322) laclq | |

| KK016 (pShiA) | amp Ptrc shiA ori (pBR322) laclq | |

| KK017 (pMdtD) | amp Ptrc mdtD ori (pBR322) laclq | |

| KK018 (pBcr) | amp Ptrc bcr ori (pBR322) laclq | |

| KK019 (pYfcJ) | amp Ptrc yfcJ ori (pBR322) laclq | |

| KK020 (pKgtP) | amp Ptrc kgtP ori (pBR322) laclq | |

| KK021 (pYgcS) | amp Ptrc ygcS ori (pBR322) laclq | |

| KK022 (pGalP) | amp Ptrc galP ori (pBR322) laclq | |

| KK023 (pNanT) | amp Ptrc nanT ori (pBR322) laclq | |

| KK024 (pYhhS) | amp Ptrc yhhS ori (pBR322) laclq | |

| KK025 (pNepI) | amp Ptrc nepI ori (pBR322) laclq | |

| KK026 (pEmrD) | amp Ptrc emrD ori (pBR322) laclq | |

| KK027 (pMdtL) | amp Ptrc mdtL ori (pBR322) laclq | |

| KK028 (pProp) | amp Ptrc proP ori (pBR322) laclq | |

| KK029 (pYjhB) | amp Ptrc yjhB ori (pBR322) laclq | |

| KK031 (pYjiO) | amp Ptrc yjiO ori (pBR322) laclq | |

| KK032 (pYdhC) | amp Ptrc ydhC ori (pBR322) laclq | |

| KK033 (PsetC-venus) | kan PsetC-venus ori p15a | |

| KK034 (PydeA-venus) | kan PydeA-venus ori p15a | |

| KK035 (PmhpT-venus) | kan PmhpT-venus ori p15a | |

| KK036 (PybdA-venus) | kan PybdA-venus ori p15a | |

| KK037 (PydeE-venus) | kan PydeE-venus ori p15a | |

| KK038 (PkgtP-venus) | kan PkgtP-venus ori p15a | |

| KK039 (Pcmr-venus) | kan Pcmr-venus ori p15a | |

| KK040 (PynfM-venus) | kan PynfM-venus ori p15a | |

| KK041 (PmdtD-venus) | kan PmdtD-venus ori p15a | |

| KK042 (PyfcJ-venus) | kan PyfcJ-venus ori p15a | |

| KK043 (PyhhS-venus) | kan PyhhS-venus ori p15a | |

| KK044 (PemrD-venus) | kan PemrD-venus ori p15a | |

| KK045 (PydhC-venus) | kan PydhC-venus ori p15a |

All plasmids are from this work unless otherwise noted.

The plasmids pKD3 and pKD4 were used as templates to generate scarred FRT mutants as previously described. Mutations were checked by PCR using primers that bound outside the deleted region. Prior to the removal of the antibiotic resistance marker, the constructs resulting from this procedure were moved into a clean wild-type background by P1vir transduction.

The plasmid pPROBE-venus was constructed by digesting the plasmid pQE80L-venus by EcoRI and NheI and cloning the fragment into pPROBE-gfp[tagless] digested by EcoRI and NheI. This replaced the gfp[tagless] by the fast-folding yfp variant Venus in pPROBE [30]. Venus transcriptional fusions were made by amplifying the promoter of interest and then cloning these PCR fragments into the multiple cloning site of pPROBE-venus . The araBAD promoter was amplified using primers TD088f (sequence: 5′- GGA AAG GTA CCC ATT CCC AGC GGT CG) and TD088r (sequence: 5′- GAC TAG AAT TCG CCA AAA TCG AGG CC). The xylA promoter was amplified using primers TD065f (sequence: 5′- GGA AAG GTA CCT CGA TCT TTT TGC CA) and TD065r (5′- GAC TAG AAT TCG CGA TCG AGC TGG TC). The PCR fragments were then digested with KpnI and EcoRI (sequences underlined) and cloned into the multiple cloning site of the pPROBE-venus vector. The resulting transcriptional fusions were transformed into the mutated strains containing the deletions of interest.

Plasmids overexpressing the genes of interest were constructed by cloning the respective gene into the multiple cloning site of pTrc99A under the control of a strong IPTG inducible promoter, Ptrc [31].

Fluorescence Assays

End-point measurements of the fluorescent reporter system were made using a Tecan Safire 2 microplate reader. 3 mL cultures were grown overnight in tryptone media at 37°C and then subcultured 1∶30 after which 0.45 mL was transferred to a single well of a polypropylene, 2.2 ml, deep, square, 96-well microtiter plate (VWR; 82006-448). Cultures were then grown at 37°C while shaking at 600 rpm on a microplate shaker (VWR). After an optical density of 0.05 was reached, the cells were induced with varying concentrations of the sugar of interest (either arabinose or xylose). Extracellular sugar concentrations ranged from 1 mM to 10 mM. In addition, strains containing the expression plasmids for the genes of interest were also induced with IPTG. Final volumes in each well were adjusted to 0.5 mL for all cultures. When the cells reached an OD of 0.4–0.5, 100 µL of the culture was transferred from the deep-well plates to black, clear-bottomed Costar 96-well microtiter plates, and the fluorescence (excitation/emission λ, 515/530 nm and OD at 600 nm (OD600) were measured. The fluorescence readings were normalized with the OD600 to account for cell density. All experiments were conducted in triplicates and average values with the standard deviations are reported.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tasha Desai for technical assistance and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful suggestions.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by the Energy Biosciences Institute. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Liu JY, Miller PF, Gosink M, Olson ER (1999) The identification of a new family of sugar efflux pumps in Escherichia coli. Molecular microbiology 31: 1845–1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Liu JY, Miller PF, Willard J, Olson ER (1999) Functional and biochemical characterization of Escherichia coli sugar efflux transporters. The Journal of biological chemistry 274: 22977–22984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Carole S, Pichoff S, Bouch JP (1999) Escherichia coli gene ydeA encodes a major facilitator pump which exports L-arabinose and isopropyl-beta-D-thiogalactopyranoside. Journal of bacteriology 181: 5123–5125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bost S, Silva F, Belin D (1999) Transcriptional activation of ydeA, which encodes a member of the major facilitator superfamily, interferes with arabinose accumulation and induction of the Escherichia coli arabinose PBAD promoter. Journal of bacteriology 181: 2185–2191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sun Y, Vanderpool CK (2011) Regulation and function of Escherichia coli sugar efflux transporter A (SetA) during glucose-phosphate stress. Journal of bacteriology 193: 143–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Danchin A (2009) Cells need safety valves. BioEssays : news and reviews in molecular, cellular and developmental biology 31: 769–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tatusov RL, Fedorova ND, Jackson JD, Jacobs AR, Kiryutin B, et al. (2003) The COG database: an updated version includes eukaryotes. BMC bioinformatics 4: 41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tatusov RL, Koonin EV, Lipman DJ (1997) A genomic perspective on protein families. Science 278: 631–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nagai T, Ibata K, Park ES, Kubota M, Mikoshiba K, et al. (2002) A variant of yellow fluorescent protein with fast and efficient maturation for cell-biological applications. Nature biotechnology 20: 87–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schleif R (2000) Regulation of the L-arabinose operon of Escherichia coli. Trends in genetics : TIG 16: 559–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Edgar R, Bibi E (1997) MdfA, an Escherichia coli multidrug resistance protein with an extraordinarily broad spectrum of drug recognition. Journal of bacteriology 179: 2274–2280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nishino K, Yamaguchi A (2001) Analysis of a complete library of putative drug transporter genes in Escherichia coli. Journal of bacteriology 183: 5803–5812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Naroditskaya V, Schlosser MJ, Fang NY, Lewis K (1993) An E. coli gene emrD is involved in adaptation to low energy shock. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 196: 803–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bohn C, Bouloc P (1998) The Escherichia coli cmlA gene encodes the multidrug efflux pump Cmr/MdfA and is responsible for isopropyl-beta-D-thiogalactopyranoside exclusion and spectinomycin sensitivity. Journal of bacteriology 180: 6072–6075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Staub JM, Brand L, Tran M, Kong Y, Rogers SG (2012) Bacterial glyphosate resistance conferred by overexpression of an E. coli membrane efflux transporter. Journal of industrial microbiology & biotechnology 39: 641–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Furrer JL, Sanders DN, Hook-Barnard IG, McIntosh MA (2002) Export of the siderophore enterobactin in Escherichia coli: involvement of a 43 kDa membrane exporter. Molecular microbiology 44: 1225–1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Han X, Dorsey-Oresto A, Malik M, Wang JY, Drlica K, et al. (2010) Escherichia coli genes that reduce the lethal effects of stress. BMC microbiology 10: 35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hayashi M, Tabata K, Yagasaki M, Yonetani Y (2010) Effect of multidrug-efflux transporter genes on dipeptide resistance and overproduction in Escherichia coli. FEMS microbiology letters 304: 12–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Seol W, Shatkin AJ (1991) Escherichia coli kgtP encodes an alpha-ketoglutarate transporter. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 88: 3802–3806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Song S, Park C (1997) Organization and regulation of the D-xylose operons in Escherichia coli K-12: XylR acts as a transcriptional activator. Journal of bacteriology 179: 7025–7032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Englesberg E, Anderson RL, Weinberg R, Lee N, Hoffee P, et al. (1962) L-Arabinose-sensitive, L-ribulose 5-phosphate 4-epimerase-deficient mutants of Escherichia coli. Journal of bacteriology 84: 137–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zgurskaya HI, Krishnamoorthy G, Ntreh A, Lu S (2011) Mechanism and Function of the Outer Membrane Channel TolC in Multidrug Resistance and Physiology of Enterobacteria. Frontiers in microbiology 2: 189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rosner JL, Martin RG (2009) An excretory function for the Escherichia coli outer membrane pore TolC: upregulation of marA and soxS transcription and Rob activity due to metabolites accumulated in tolC mutants. Journal of bacteriology 191: 5283–5292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ferguson GP, Totemeyer S, MacLean MJ, Booth IR (1998) Methylglyoxal production in bacteria: suicide or survival? Archives of microbiology 170: 209–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ackerman RS, Cozzarelli NR, Epstein W (1974) Accumulation of toxic concentrations of methylglyoxal by wild-type Escherichia coli K-12. Journal of bacteriology 119: 357–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Postma PW, Lengeler JW, Jacobson GR (1993) Phosphoenolpyruvate:carbohydrate phosphotransferase systems of bacteria. Microbiological reviews 57: 543–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chubiz LM, Rao CV (2010) Aromatic acid metabolites of Escherichia coli K-12 can induce the marRAB operon. Journal of bacteriology 192: 4786–4789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Datsenko KA, Wanner BL (2000) One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 97: 6640–6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller JH (1992) A Short Course in Bacterial Genetics: A Laboratory Manual for Escherichia coli and Related Bactera. Cold Spring Harbor: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory.

- 30. Lindsay SE, Bothast RJ, Ingram LO (1995) Improved Strains of Recombinant Escherichia-Coli for Ethanol-Production from Sugar Mixtures. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 43: 70–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Amann E, Ochs B, Abel KJ (1988) Tightly regulated tac promoter vectors useful for the expression of unfused and fused proteins in Escherichia coli. Gene 69: 301–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Desai TA, Rao CV (2010) Regulation of arabinose and xylose metabolism in Escherichia coli. Applied and environmental microbiology 76: 1524–1532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cherepanov PP, Wackernagel W (1995) Gene disruption in Escherichia coli: TcR and KmR cassettes with the option of Flp-catalyzed excision of the antibiotic-resistance determinant. Gene 158: 9–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]