Abstract

The combined use of surface plasmon resonance (SPR) and modified or mimic oligonucleotides have expanded diagnostic capabilities of SPR-based biosensors and have allowed detailed studies of molecular recognition processes. This review summarizes the most significant advances made in this area over the past 15 years.

Functional and conformationally restricted DNA analogs (e.g., aptamers and PNAs) when used as components of SPR biosensors contribute to enhance the biosensor sensitivity and selectivity. At the same time, the SPR technology brings advantages that allows forbetter exploration of underlying properties of non-natural nucleic acid structures such us DNAzymes, LNA and HNA.

Keywords: DNAzyme, LNA, PNA, SPR, aptamer, biosensors

Introduction

The advent of click chemistry1 has led to the design of DNA analogs with modified nucleobases and backbones,2 thus allowing the development of a new generation of “smart” systems useful for chemical and biological applications.3 As a consequence of those synthetic efforts DNA analogs with improved stability, functionality and binding characteristics and with properties not present in natural nucleic acids have been produced.4 The new nucleic acid analogs have been also produced with the aim to develop innovative therapeutic agents5 or new tools for diagnostics.6

Aptamers7 and DNAzymes,8 collectively referred to as functional nucleic acids, are RNA or DNA structures with binding and catalytic properties respectively. These systems have sequence-specific folds9 that achieve their tertiary folds and activities through a combination of different molecular interactions and motifs.10 Unfortunately, the use of functional nucleic acids in therapeutics has been hampered by their denaturation and/or biodegradation in body fluids. In this perspective, artificial nucleosides with unusual structural features may offer improved half-life in vivo, better structural stability, and could represent innovative systems to be used as novel interacting groups. Examples of promising non-natural nucleosides include conformationally restricted oligonucleotides such as peptide nucleic acid (PNA),11 locked nucleic acid (LNA),12 hexitol nucleic acid (HNA)13 and phosphoramidates morpholino (MORFs)14 oligomers.

Specific properties of artificial nucleosides have contributed to the development of more efficient tools for biosensing. In fact, artificial nucleoside probes have been used in combination with a number of different transduction platforms in order to achieve an even more sensitive and selective detection of nucleic acids and proteins.

Among the different platforms for multiplexed detection of protein markers and nucleic acids available, SPR15 has the greatest potential.16 In fact, recent improvements in instrumental and experimental design17 together with important features such as being real-time, label-free and having sensitive detection, make SPR a key technology for a wide range of potential therapeutic and diagnostic applications.18,19

The SPR phenomenon20 occurs when a plane-polarized radiation interacts with a metal film under total internal reflection conditions. At a specific incidence angle of the incoming radiation the intensity of the reflected light is attenuated. The resonance angle is dependent on the thickness and dielectric constant of both the metal film as well as its interfacing region. Keeping all the other conditions constant, the binding of molecules to the metal surface modifies the dielectric constant of the interface region, thus changing incident light/surface plasmons coupling conditions and the resonance angle. SPR experiments involve immobilizing one reactant on a metal surface (typically gold) and monitoring the reactant interaction with a second component which is typically available as a solute in a solution that flows over the sensor surface through a microfluidic cell.21

The SPR-based sensing benefits from the label-free detection22 and is useful for quantitative analysis and equilibrium and kinetic constants determination.23

In this paper, the state of the art technology of the currently available SPR applications based on functional and conformationally restricted artificial nucleic acids will be reviewed with specific attention to applications in diagnostics and detection of clinically relevant targets demonstrated over the past 15 years. A special emphasis will be given to DNA-like compounds such as aptamers and PNAs, which exhibit many advantages as recognition elements in biosensing when compared with traditional antibodies and DNA probes, respectively. In particular, this review will be aimed at introducing the SPR approach and at displaying how artificial DNAs can serve as bioreceptor components in SPR biosensing, while eliminating some processing steps that affect multiplex analysis capabilities. Moreover, this review will try to show how useful SPR is in addressing challenges associated with the study of artificial DNAs.

Due to the specific attention to applications in diagnostics and detection of clinically relevant targets this review will highlight those applications able to meet enhanced sensitivity requirements useful for their use in real matrices. Selected applications demonstrating lower sensitivity in target detection will be discussed when associated with significant advantages, such as the simplicity of the detection scheme or the use of innovative detection strategies. In this perspective, this review complements the existing ones from the past that mostly demonstrated the basic possibilities offered by SPR sensing and DNA analogs on model systems for proof-of-concept emphasis.

Functional DNA Analogs

Functional DNA analogs play a prominent role in important biotechnological fields.24 In this review a selection of functional DNA analogs will be discussed with particular reference to their differential binding properties investigated by using SPR. The increasing number of synthesized functional DNA analogs renders their chemical and biochemical characterizations even more challenging. In this context, SPR plays an important role thanks to the possibility it offers to determine binding constants. In addition, SPR is used as the transducer of functional DNA analog-based sensing platforms.

Aptamers and SPR

DNA or RNA aptamers are artificial single-stranded oligonucleotide able to bind molecular targets with high specificity. They can be viewed as chemical complements to antibodies.25 Aptamers offer good chemical stability, high selectivity and high affinity toward their targets and can easily chemically modified, thus making them promising tools for bioanalytic26 and diagnostic applications.27,28 In particular, aptamers29,30 have emerged as promising recognition elements for SPR biosensors,31 since they offer the opportunity to achieve an enhanced specific and sensitive SPR detection.24 Aptamers offers many advantages compared with antibodies related to their chemical production based on an in vitro selection process, the possibility to be optimized for conditions different than the physiological conditions needed by antibodies, their stability, the possibility tolerate repeated cycles of denaturation and regeneration, easy chemical modification without affecting their affinity, the possibility to interact with high affinity with toxins as well as molecules that do not elicit good immune response.32

SPR detection based on aptamers has been used with different aims. Misono and Kumar33 have used the SPR detection in order to select an RNA aptamer for the human influenza A/Panama/2007/1999 (H3N2) virus. A pool of RNA sequences constituting a random RNA library was adsorbed on an SPR chip previously coated with the influenza A/Panama virus. After the RNA interaction and the surface washing, RNA sequences specifically adsorbed on the virus were recovered and amplified for the next selection round. The process selected an aptamer specific for the haemagglutinin (HA) of influenza A with a general recognition motif as 5′-GUCGNCNU(N)2-3GUA-3′.

The SPR-based aptamer selection method benefits from the repeated use of an immobilized target and allows the identification of binding species in fractions besides providing information about the target binding ability of molecules before they have been selected.

SPR biosensors are also used to screen and to characterize aptamers. In this perspective, aptamer-based SPR analysis has been used to detect the human IgE,34 the C-reactive protein35 and the HIV-1 Tat protein.36

The use of enzymes to generate precipitants has been recently proposed as a strategy to generate enhanced SPR signals.37 In particular, an enzymatically-amplified SPR imaging (SPRi) assay has been developed to detect thrombin, a protease with anticoagulant functions, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), a potential biomarker for rheumatoid arthritis and various cancers.38 The detection protocol benefited from the use of surface bound aptamers to immobilize the targeted protein. A horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated antibody was then adsorbed onto the immobilized target thus creating an aptamer target-antibody sandwich structure. The complex when exposed to the HRP substrate formed a precipitate on the SPRi sensor surface that caused a significantly amplified SPRi response. A high sensitivite detection of the target proteins was thus obtained (limit-of-detections for thrombin and VEGF were 500 fM and 1 pM, respectively).

A DNA aptamer specific for retinol binding protein 4 (RBP4), a biomarker for insulin resistance and type II diabetes, was used to develop an SPR biosensor.39 The developed SPR biosensor performances rivalled those of existing antibody-based assays for RBP4 with the additional advantage of being reusable.

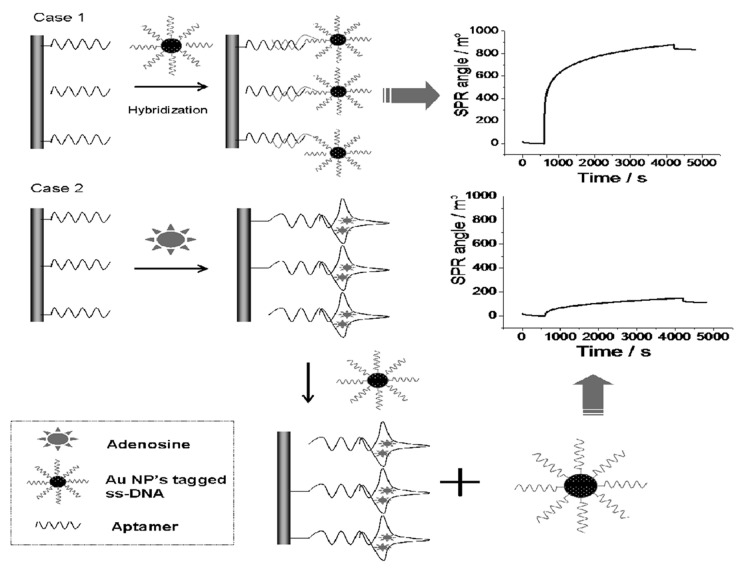

Besides the capture and the identification of proteins as biomarkers, the aptamer-based SPR analysis has recently been applied to the detection of small molecules. Small molecules are detected with difficulty by conventional SPR due to the reduced change in the refractive index they cause. A non-conventional approach based on an SPR surface inhibition combining the SPR signal amplification produced by gold nanoparticles (AuNPs)40 with the use of aptamers has been developed to detect adenosine, an important biological cofactor (Fig. 1).41 The aptamer was first immobilized on the SPR sensor metallic gold surface. The random and coiled ssDNA structure of the selected aptamer allowed the hybridization with a complementary ssDNA previously tagged to AuNPs thus producing a large change in the detected SPR signal. However, when adenosine was introduced into the SPR cell, the structural change of the aptamer prevented the AuNPs-tagged hybridization. The reduction of the SPR signal was linearly proportional to the concentration of adenosine over the 1 nM to 1 µM concentration range.

Figure 1. Schematic description of the protocol used to detect adenosine by using an aptamer-based gold nanoparticle enhanced SPR protocol. Reproduced with permission by the American Chemical Society.41

The AuNPs amplification effect has also been exploited by using aptamer-Au NPs conjugates for the detection of the human immunoglobulin E (IgE).42 In this case an LOD of 1 ng/mL was obtained.

Aptamer beacons have been used in combination with SPR for the detection of interferon gamma (IFN-γ).43 In this case, a fluorescence signal was generated directly upon the binding of IFN-γ. However, fluorescence-based sensors suffer from the limited stability and the photobleaching of fluorophores so the electrochemical detection of redox-labeled aptamers was more effective.44 The experiment was conducted by immobilizing a thiolated DNA hairpin containing a methylene blue (MB) IFN-γ-binding aptamer on a gold electrode. The IFN-γ binding caused the aptamer hairpin to unfold, pushing MB redox molecules away from the electrode and decreasing electron-transfer efficiency. The assembly of aptamers and the IFN-γ subsequent binding were investigated with SPR, while the change in the measured current was quantified by square wave voltammetry (SWV). The sensor was specific to IFN-γ even in the presence of overabundant serum proteins and its surface regeneration was obtained by disrupting the aptamer-IFN-γ complex with urea.

DNAzymes and SPR

Whereas the specific binding properties of aptamers have been exploited to develop specific and sensitive biosensors,45 catalytic nucleic acids such as DNAzymes46 have been used as labels to amplify biosensing events.47 DNAzymes operate by stimulating the peroxidase activity48 or by inducing hydrolytic reactions.49 Moreover, aptamers have been combined with DNAzymes to form allosteric DNAzymes50 or aptazymes whose functions extend beyond the Watson–Crick base pair recognition of complementary strands49 since DNAzymes are DNA-based biocatalysts capable of performing chemical transformations.51,52

The most studied DNAzyme is the “10-23” subtype comprising a cation dependent 15 deoxyribonucleotides catalytic core that binds to and cleaves its RNA target by producing a 2’,3′-cyclic phosphate and a 5′-hydroxyl termini.53

DNAzymse catalysis is highly dependent on the formation of tertiary structures, on the presence and concentration of metal ions and on stereochemical effects.

The Mg2+ induced conformational change of a DNAzyme targeting the β3 integrin mRNA has been studied by using SPR.54 DNAzyme undergone several conformational rearrangements that were responsible of an enhanced enzymatic activity as the Mg2+ concentration was increased from 0 to 25 mM. An efficient cleavage was obtained only when the Mg2+ concentration was much higher than its physiological concentration, thus suggesting the selected DNAzyme might be inactive in transfected cells and operated via an antisense mechanism.

Conformationally Restricted DNA Analogs

The members the conformationally restricted oligonucleotide family designed to target single stranded DNA and RNA has kept rapidly growing since its introduction in 1993.55 The following sections focus on selected structures showing superior base-pairing properties while SPR key limitations are centered on the issues of sensitivity and selectivity.

PNA and SPR

PNAs are non-natural informational molecules containing a neutral peptide-like backbone and heterocyclic bases of DNA.56 In this case, the phosphate linkage found in DNA and RNA is replaced by a 2-aminoethylglycine peptide backbone. PNAs have unique properties that have been exploited for many molecular biology and biochemical applications.57,58 PNA oligonucleotides hybridize to complementary RNA or DNA by normal Watson-Crick base pairing with higher affinity and specificity than normal oligonucleotides, and bind strongly under conditions in which normal nucleic acid hybrids are disfavored. On account of their outstanding properties, PNAs have been proposed as valuable alternatives to oligonucleotide probes.59-61

The uncharged nature of PNAs brings fundamental advantages to surface hybridization technologies such as SPR. Among them reduced needs in terms of ionic strength control to obtain the hybridization between PNA probes and complementary strands when compared with DNA probes.

Several research groups have applied the SPR technology to study the DNA hybridization with PNA since the end of 1990s.62-64 At that time efforts were paid in demonstrating advantages offered by PNA in DNA recognition. In addition, the use of surface plasmon-allied techniques, such as the surface plasmon field enhanced fluorescence spectroscopy (SPFS), in DNA detection by PNAs has also been accounted.65-67

The use of surface-immobilized PNA probes in SPR detection provides a powerful tool for the study of pathogen DNAs. Kai et al.68 demonstrated the SPR detection of oligonucleotides obtained after the PCR amplification of DNA from E. coli O157:H7 in stool samples. A biotinylated PNA probe sequence was immobilized on a streptavidin coated surface and the PCR products were detected with a LOD of 102 cfu/0.1 g of stool.

Mismatched base pairs in PNA:DNA hybrids are quite unstable, so PNA probes can be used to efficiently detect single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs).69,70 This specific properties of PNAs has been used to detect the K-ras gene point mutation by immobilizing a 15-mer biotinylated PNA probes on the SPR sensor surface.71 The ability of PNA and DNA probes to discriminate point mutation was investigated and the importance of the temperature for the SPR detection of a G-G mismatch in PNA/DNA or DNA/DNA interactions was revealed.

The specific peculiarity of PNAs in SNPs detection has been also exploited in detecting the cystic fibrosis gene W1282X point mutation.72 Experiments were conducted by using target DNA oligomers, PNA oligomers and chiral PNA oligomers and it was demonstrated that PNAs carrying chiral monomers can be used to alter the affinity and the selectivity for the cDNA.73 Chiral PNA oligomers were selected to contain a “chiral box” carrying three nucleotides with chiral monomers based on d-lysine. Experiments based on chiral PNAs showed an enhanced mismatch recognition. Moreover, hybridization energetic was shown to be superior when compared with both DNA oligomers and achiral PNA sequences. It was also found that chiral PNA/DNA hybrids were less stable when hybridization occurred at the solid interface rather than in solution.74

SPR imaging (SPRi) is a convenient tool for label-free and multiplexed biosensing75 that couples the sensitivity of spectral SPR measurements with spatially-controlled imaging capabilities.76 It involves exciting a relatively broad area of the sensor surface which has been pre-arrayed with series of biorecognition sites.77 Since SPRi is capable of monitoring the amount and the distribution of molecules adsorbed on the metal surface in real time, it is an ideal tool for the study of the binding of molecules to arrays of surface-bound species78 with high-throughput and low sample consumption thanks to its easy coupling to microfluidic devices.79,80

Detection of DNA and RNA molecules in biological samples has had a central role in genomics research.81 However, the use of SPRi for genomic research has been limited by the reduced sensitivity in detecting DNA or RNA hybridization. A number of different strategies aimed at amplifying the SPRi response to DNA hybridization have been investigated82-84 and the possibility to achieve detection limits useful for the non-amplified DNA detection has been demonstrated by using AuNPs to enhance the SPRi sensitivity.85

The most effective approach for the SPRi nucleic acid detection so far proposed is based on a sandwich detection protocol. The protocol relies on PNA capture probes immobilized onto the gold SPRi sensor surface while the SPRi enhanced detection of the captured target DNA is obtained by using AuNPs previously conjugated to an oligonucleotide sequence complementary to a tract of the target DNA not involved in the hybridization with the PNA probe.86 This method successfully demonstrated the ultrasensitive detection of oligonucleotide sequences down to 1 fM by maintaining a good selectivity in the recognition of single nucleotide mismatches.87 Moreover, it has been shown to be able to detect GMO sequences in non-amplified genomic DNA extracted from soybean flour.88

The direct detection of genomic DNAs with no need for PCR amplification represents an important step toward the development of simpler, cheaper and more reliable detection methods. The specificity and sensitivity provided by the method combining PNA probes and the nanoparticle-enhanced SPRi detection allowed the identification of a genetically modified (GM) target sequence down to zM concentrations in solutions containing a total of GM and GM-free genomic DNA aM in concentration (10 pg μL−1) thus supplying a new tool for the PCR -free and multiplexed detection of genomic DNA.

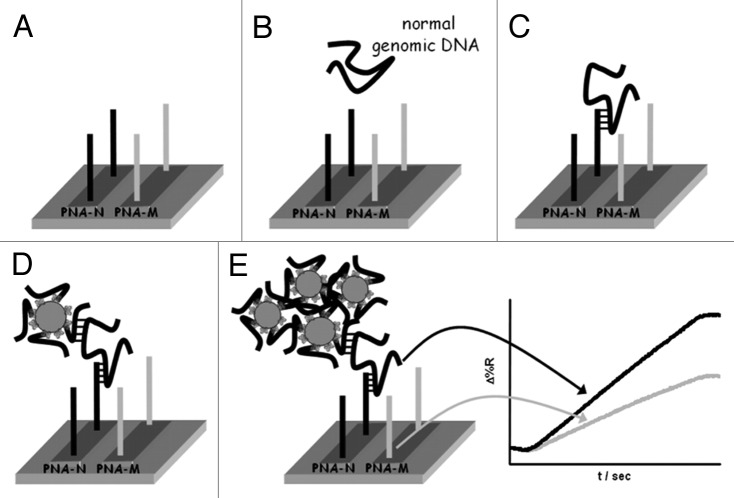

A similar detection strategy was successfully used for the direct detection of a point mutation related to the β-thalassemia disease in non-amplified genomic DNA obtained from blood samples.89 In this case normal, homozygous and heterozygous genomic DNA samples were directly fluxed into each of six microchannels of the SPRi fluidic system in order to allow the direct interaction of each of the three samples with two different PNA probes complementary to the normal (PNA-N) and mutated (PNA-M) DNA sequences, respectively (Fig. 2). The two different PNA probes were useful both to discriminate between normal, homozygous, and heterozygous DNAs as well as to avoid the use of external controls which were difficult to be obtained for this specific application. The specific SPRi response patterns obtained when normal, homozygous, or heterozygous DNAs were each allowed to interact with the two different PNA probes provided a robust experiment control. In fact, whereas normal DNA was expected to interact with only the PNA-N probe (Fig. 2), different interactions were expected from homozygous and heterozygous DNAs, i.e., interaction between homozygous DNA and only the PNA-M probe and interactions between heterozygous DNA and both PNA-N and PNA-M probes.

Figure 2. Pictorial description of the nanoparticle-enhanced SPRI strategy used to detect the normal, heterozygous and homozygous genomic DNAs. PNA-N and PNA-M specifically recognize the normal β-globin and the mutated β°39-globin genomic sequences respectively. Reproduced with permission by the American Chemical Society.89

The ultrasensitive detection of the genomic DNA was achieved by using AuNPs conjugated to an oligonucleotide complementary to a tract of the target DNA not involved in the hybridization with the PNA probe.

Cationic AuNPs were also used for SPR signal amplification through ionic interaction with 16S rRNA (rRNA) hybridized to PNA probe previously immobilized on an SPR sensor chip.90 16S rRNA was used as a genetic marker for the identification of E. coli organisms. The hybridization between the neutral PNA and 16S rRNA resulted in a change of the ionic condition from neutral to negative. The method resulted in a detection limit of E. coli rRNA of 58.2 ± 1.37 pg ml−1.

LNA and SPR

LNAs12,91 first described by Wengel and coworkers in 1998, are synthetic RNA derivatives in which the ribose moiety in sugar-phosphate backbone is structurally constrained by a methylene bridge between the 2’-oxygen and the 4’-carbon atoms. The bicyclic structure locks the molecule in a C3′-endo sugar (N-type) configuration and forces the oligonucleotide in a A-form helix thus causing an excellent duplex stability, not compromising its sequence specificity. LNAs, which were synthesized as ideal oligomers for the RNA sequences recognition,92,93 do not suffer from PNAs limited solubility and tendency to aggregate.94

MicroRNA (miRNA) are non-coding RNAs that play a key role in the regulation of gene expression, acting as post-transcriptional regulators by base-pairing with their target mRNAs. Mature miRNAs are short molecules (about 22 nucleotides) which regulate a wide range of biological functions from cell proliferation and death to cancer progression.95

Fang et al.96 designed an SPRi-based miRNA detection method taking advantage of a multistep surface reaction protocol based on LNA probes. The specific design of LNA probes produced a 10-fold increase in sensitivity and improved the hybridization discrimination among similar miRNAs.97 The binding of miRNAs to the LNAs array was directly monitored by SPRi. However, the detection of low-abundance species required specific SPR signal amplification obtained after the hybridization of poly(T)-coated AuNPs to poly(A) tails added to the 3′ end of miRNAs captured on the array. The approach allowed the detection of miRNAs down to 10 fM.

HNA and SPR

The study of base-pairing properties of a variety of six-membered carbohydrate mimics with RNA shows that RNA can cross-pair with a broad range of nucleic acid structures.98,99 In particular, anhydrohexitol nucleic acid (HNA),13 a homolog of DNA, was found to be particularly stable, by forming cross-pairs with RNA more stable than that formed by RNA. HNA can be regarded as a close analog to DNA with the only difference that the base is moved from the 1’ to the 2’ position.

HNA oligonucleotides have been studied with the aim to develop an efficient anti-HIV inhibitor by targeting the transactivator responsive region (TAR) of the HIV-1 RNA genome.100 SPR has been used to show that a fully HNA-modified aptamer is a poor TAR ligand while mixmers containing both HNA and unmodified RNA nucleotides interact with dissociation constants in the low-nanomolar range and show a reduced nuclease sensitivity.

MORFs oligomers and SPR

Molecular targeting often involves the delivery of therapeutic radioisotopes to specific disease biomarkers expressed on a cell membrane. The use of DNA-like oligomers, such as phosphodiester DNAs, PNAs and phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomers (MORFs) in the design of radiopharmaceuticals would benefit from an improved understanding of their in vitro properties and their behavior in vivo.

In radiopharmaceuticals, tumor pretargeting101 is being investigated as a method proven to be effective in tumor imaging and therapy. The method is based on the targeting of tumor with an antibody containing a secondary recognition moiety. MORFs have been extensively studied for tumor pretargeting applications14 and SPR have contributed to the study of their properties. In particular, SPR has been used to understand whether a specific bivalent MORF exhibited bimolecular binding and whether the MORFs showed improved in vitro hybridization affinity in the bivalent form compared with the monovalent form.102 The results showed that bivalency may be superior to monovalency in MORF pretargeting applications.

Conclusions

In this review, an overview of advances in the use of SPR-based sensors employing DNA-like molecules is given. Aptamers and PNAs exhibit many advantages as recognition elements in biosensing when compared with traditional antibodies and DNA probe, respectively. A number of different studies supports the importance of specific features of these DNA analogs. Such features have led SPR biosensors to exhibit higher selectivity and sensitivity in detecting biomolecular targets. In addition, the SPR investigation of DNA analogs and mimics, such us DNAzyme, LNA, HNA and MORF oligomers has significantly improved our understanding of biomolecular interactions.

The combined use of SPR biosensing with DNA analogs is expected to provide significant improvements in those fields that benefit from the enhanced target detection sensitivity and selectivity combined with the label-free detection protocol and capabilities for high-throughput analyses. The above mentioned benefits have been already shown to be useful to limit biochemical sample manipulation needs and PCR amplification of nucleic acid targets thus reducing analysis time and costs. More specifically the combined use of SPR biosensors and DNA analogs can provide breakthroughs in important areas such as non-invasive early disease detection and biomarker discovery.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge support from MIUR (PRIN 2009 n 20093N774P, FIRB RBRN07BMCT)

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/artificialdna/article/21383

References

- 1.El-Sagheer AH, Brown T. Click chemistry with DNA. Chem Soc Rev. 2010;39:1388–405. doi: 10.1039/b901971p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sinha ND, Michaud DP. Recent developments in the chemistry, analysis and control for the manufacture of therapeutic-grade synthetic oligonucleotides. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel. 2007;10:807–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Navani NK, Li Y. Nucleic acid aptamers and enzymes as sensors. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2006;10:272–81. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Di Giusto DA, King GC. Special-Purpose Modifications and Immobilized Functional Nucleic Acids for Biomolecular Interactions. Top Curr Chem. 2006;261:131–68. doi: 10.1007/b136673. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Micklefield J. Backbone modification of nucleic acids: synthesis, structure and therapeutic applications. Curr Med Chem. 2001;8:1157–79. doi: 10.2174/0929867013372391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bell NM, Micklefield J. Chemical modification of oligonucleotides for therapeutic, bioanalytical and other applications. Chembiochem. 2009;10:2691–703. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200900341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weigand B-S, Zerressen A, Schlatterer JC, Helm M, Jaschke A. In vitro selection of short, catalytically active oligonucleotides; In The Aptamer Handbook: Functional Oligonucleotides and Their Applications, Klussmann, S., Ed.; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA: Weinheim, Germany, 2006; Volume 1, pp. 211-227. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pan W, Clawson GA. Catalytic DNAzymes: derivations and functions. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2008;8:1071–85. doi: 10.1517/14712598.8.8.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doessing H, Vester B. Locked and unlocked nucleosides in functional nucleic acids. Molecules. 2011;16:4511–26. doi: 10.3390/molecules16064511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagaswamy U, Voss N, Zhang Z, Fox GE. Database of non-canonical base pairs found in known RNA structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:375–6. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nielsen PE. Peptide nucleic acids (PNA) in chemical biology and drug discovery. Chem Biodivers. 2010;7:786–804. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.201000005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koshkin AA, Singh SK, Nielsen P, Rajwanshi VK, Kumar R, Meldgaard M, et al. LNA (Locked Nucleic Acids): Synthesis of the adenine, cytosine, guanine, 5-methylcytosine, thymine and uracil bicyclonucleoside monomers, oligomerisation, and unprecedented nucleic acid recognition. Tetrahedron. 1998;54:3607–30. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4020(98)00094-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hendrix C, Rosemeyer H, Verheggen I, Seela F, Van Aerschot A, Herdewijn P. 1′, 5′ -Anhydrohexitol Oligonucleotides: Synthesis, Base Pairing and Recognition by Regular Oligodeoxyribonucleotides and Oligoribonucleotides. Chemistry. 1997;3:110–20. doi: 10.1002/chem.19970030118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schultz RG, Gryaznov SM. Oligo-2′-fluoro-2′-deoxynucleotide N3′-->P5′ phosphoramidates: synthesis and properties. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:2966–73. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.15.2966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liedberg B, Nylander C, Lundström I. Biosensing with surface plasmon resonance-how it all started. Biosens Bioelectron. 1995;10:R1–9. doi: 10.1016/0956-5663(95)96965-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chandra H, Reddy PJ, Srivastava S. Protein microarrays and novel detection platforms. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2011;8:61–79. doi: 10.1586/epr.10.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Phillips KS, Cheng Q. Recent advances in surface plasmon resonance based techniques for bioanalysis. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2007;387:1831–40. doi: 10.1007/s00216-006-1052-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Piliarik M, Vaisocherová H, Homola J. Surface plasmon resonance biosensing. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;503:65–88. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-567-5_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haes AJ, Duyne RP. Preliminary studies and potential applications of localized surface plasmon resonance spectroscopy in medical diagnostics. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2004;4:527–37. doi: 10.1586/14737159.4.4.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shalabney A., Abdulhalim I. Sensitivity-enhancement methods for surface plasmon sensors. Laser Photonics Rev. 2011;5:571–606. doi: 10.1002/lpor.201000009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jonnson U, Malmqvist M. In Advances in Biosensors; Turner, A., Ed.; JAI Press Ltd.: San Diego, 1992, 291. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Homola J. Surface plasmon resonance sensors for detection of chemical and biological species. Chem Rev. 2008;108:462–93. doi: 10.1021/cr068107d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schasfoort RBM, Tudos AJ, eds. Handbook of Surface Plasmon Resonance 2008, 401 p. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu J, Cao Z, Lu Y. Functional nucleic acid sensors. Chem Rev. 2009;109:1948–98. doi: 10.1021/cr030183i. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jayasena SD. Aptamers: an emerging class of molecules that rival antibodies in diagnostics. Clin Chem. 1999;45:1628–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aptamers in Bioanalysis. M. Mascini (Ed.), John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New Jersey, U.S.A., 2009, pp. 63-86. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bhosale AV, Hardikar SR, Naresh P, Bhujbal PU, Khirsagar AA, Malvankar SR. Oligonucleotide based therapeutics: aptamers. Res J Phar Tec. 2009;2:449–55. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Di Fusco M, Tortolini C, Frasconi M, Mazzei F. Aptamer-based and DNAzyme-based biosensors for environmental monitoring. Int J Environ Health. 2011;5:186–204. doi: 10.1504/IJENVH.2011.041327. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ellington AD, Szostak JW. In vitro selection of RNA molecules that bind specific ligands. Nature. 1990;346:818–22. doi: 10.1038/346818a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robertson DL, Joyce GF. Selection in vitro of an RNA enzyme that specifically cleaves single-stranded DNA. Nature. 1990;344:467–8. doi: 10.1038/344467a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Song S, Wang L, Li J, Zhao J, Fan C. Aptamer-based biosensors. Trends Analyt Chem. 2008;7:108–17. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2007.12.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mascini M, Palchetti I, Tombelli S. Nucleic acid and peptide aptamers: fundamentals and bioanalytical aspects. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2012;51:1316–32. doi: 10.1002/anie.201006630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Misono TS, Kumar PKR. Selection of RNA aptamers against human influenza virus hemagglutinin using surface plasmon resonance. Anal Biochem. 2005;342:312–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2005.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim YH, Kim JP, Han SJ, Sim SJ. Aptamer biosensor for label-free detection of human immunoglobulin E based on surface plasmon resonance. Sens Actuators B Chem. 2009;139:471–5. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2009.03.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bini A, Centi S, Tombelli S, Minunni M, Mascini M. Development of an optical RNA-based aptasensor for C-reactive protein. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2008;390:1077–86. doi: 10.1007/s00216-007-1736-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tombelli S, Minunni M, Luzi E, Mascini M. Aptamer-based biosensors for the detection of HIV-1 Tat protein. Bioelectrochemistry. 2005;67:135–41. doi: 10.1016/j.bioelechem.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li Y, Lee HJ, Corn RM. Detection of protein biomarkers using RNA aptamer microarrays and enzymatically amplified surface plasmon resonance imaging. Anal Chem. 2007;79:1082–8. doi: 10.1021/ac061849m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kuramochi H, Hayashi K, Uchida K, Miyakura S, Shimizu D, Vallböhmer D, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor messenger RNA expression level is preserved in liver metastases compared with corresponding primary colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:29–33. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee SJ, Youn BS, Park JW, Niazi JH, Kim YS, Gu MB. ssDNA aptamer-based surface plasmon resonance biosensor for the detection of retinol binding protein 4 for the early diagnosis of type 2 diabetes. Anal Chem. 2008;80:2867–73. doi: 10.1021/ac800050a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zanoli LM, D’Agata R, Spoto G. Functionalized gold nanoparticles for ultrasensitive DNA detection. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2012;402:1759–71. doi: 10.1007/s00216-011-5318-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang J, Zhou HS. Aptamer-based Au nanoparticles-enhanced surface plasmon resonance detection of small molecules. Anal Chem. 2008;80:7174–8. doi: 10.1021/ac801281c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang J, Munir A, Li Z, Zhou HS. Aptamer-Au NPs conjugates-enhanced SPR sensing for the ultrasensitive sandwich immunoassay. Biosens Bioelectron. 2009;25:124–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tuleuova N, Jones CN, Yan J, Ramanculov E, Yokobayashi Y, Revzin A. Development of an aptamer beacon for detection of interferon-gamma. Anal Chem. 2010;82:1851–7. doi: 10.1021/ac9025237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu Y, Tuleouva N, Ramanculov E, Revzin A. Aptamer-based electrochemical biosensor for interferon gamma detection. Anal Chem. 2010;82:8131–6. doi: 10.1021/ac101409t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tombelli S, Minunni M, Mascini M. Analytical applications of aptamers. Biosens Bioelectron. 2005;20:2424–34. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Willner I, Shlyahovsky B, Zayats M, Willner B. DNAzymes for sensing, nanobiotechnology and logic gate applications. Chem Soc Rev. 2008;37:1153–65. doi: 10.1039/b718428j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li D, Shlyahovsky B, Elbaz J, Willner I. Amplified analysis of low-molecular-weight substrates or proteins by the self-assembly of DNAzyme-aptamer conjugates. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:5804–5. doi: 10.1021/ja070180d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Travascio P, Bennet AJ, Wang DY, Sen D. A ribozyme and a catalytic DNA with peroxidase activity: active sites versus cofactor-binding sites. Chem Biol. 1999;6:779–87. doi: 10.1016/S1074-5521(99)80125-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Breaker RR. Natural and engineered nucleic acids as tools to explore biology. Nature. 2004;432:838–45. doi: 10.1038/nature03195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Teller C, Shimron S, Willner I. Aptamer-DNAzyme hairpins for amplified biosensing. Anal Chem. 2009;81:9114–9. doi: 10.1021/ac901773b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Breaker RR. DNA enzymes. Nat Biotechnol. 1997;15:427–31. doi: 10.1038/nbt0597-427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Achenbach JC, Chiuman W, Cruz RPG, Li Y. DNAzymes: from creation in vitro to application in vivo. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2004;5:321–36. doi: 10.2174/1389201043376751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Santoro SW, Joyce GF. A general purpose RNA-cleaving DNA enzyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:4262–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cieslak M, Szymanski J, Adamiak RW, Cierniewski CS. Structural rearrangements of the 10-23 DNAzyme to beta 3 integrin subunit mRNA induced by cations and their relations to the catalytic activity. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:47987–96. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300504200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tarkoy M, Leumann C. Synthesis and Pairing Properties of Decanucleotides from (3′S,5′R)-2′-Deoxy-3′, 5′-ethanoß-D-ribofuranosyladenine and –thymine. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1993;32:1432–4. doi: 10.1002/anie.199314321. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nielsen PE. Peptide Nucleic Acid. A Molecule with Two Identities. Acc Chem Res. 1999;32:624–30. doi: 10.1021/ar980010t. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nielsen PE. Peptide nucleic acid: a versatile tool in genetic diagnostics and molecular biology. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2001;12:16–20. doi: 10.1016/S0958-1669(00)00170-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gambari R. Peptide-nucleic acids (PNAs): a tool for the development of gene expression modifiers. Curr Pharm Des. 2001;7:1839–62. doi: 10.2174/1381612013397087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chu LQ, Foerch R, Knoll W. Surface-Plasmon-Enhanced Fluorescence Spectroscopy for DNA Detection Using Fluorescently Labeled PNA as “DNA Indicator”. Angew Chem. 2007;119:5032–5. doi: 10.1002/ange.200605247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sforza S, Corradini R, Tedeschi T, Marchelli R. Food analysis and food authentication by peptide nucleic acid (PNA)-based technologies. Chem Soc Rev. 2011;40:221–32. doi: 10.1039/b907695f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zanoli LM, Licciardello M, D’Agata R, Lantano C, Calabretta A, Corradini R, et al. Peptide nucleic acid molecular beacons for the detection of PCR amplicons in droplet-based microfluidic devices. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s00216-011-5638-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sawata S, Kai E, Ikebukuro K, Iida T, Honda T, Karube I. Application of peptide nucleic acid to the direct detection of deoxyribonucleic acid amplified by polymerase chain reaction. Biosens Bioelectron. 1999;14:397–404. doi: 10.1016/S0956-5663(99)00018-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Burgener M, Sänger M, Candrian U. Synthesis of a stable and specific surface plasmon resonance biosensor surface employing covalently immobilized peptide nucleic acids. Bioconjug Chem. 2000;11:749–54. doi: 10.1021/bc0000029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jensen KK, Ørum H, Nielsen PE, Nordén B. Kinetics for hybridization of peptide nucleic acids (PNA) with DNA and RNA studied with the BIAcore technique. Biochemistry. 1997;36:5072–7. doi: 10.1021/bi9627525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kambhampati D, Nielsen PE, Knoll W. Investigating the kinetics of DNA-DNA and PNA-DNA interactions using surface plasmon resonance-enhanced fluorescence spectroscopy. Biosens Bioelectron. 2001;16:1109–18. doi: 10.1016/S0956-5663(01)00239-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Knoll W, Park H, Sinner EK, Yao D, Yu F. Supramolecular interfacial architectures for optical biosensing with surface plasmons. Surf Sci. 2004;570:30–42. doi: 10.1016/j.susc.2004.06.192. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yu F, Persson B, Löfås S, Knoll W. Attomolar sensitivity in bioassays based on surface plasmon fluorescence spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:8902–3. doi: 10.1021/ja048583q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kai E, Ikebukuro K, Hoshina S, Watanabe H, Karube I. Detection of PCR products of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in human stool samples using surface plasmon resonance (SPR) FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2000;29:283–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2000.tb01535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ratilainen T, Holmén A, Tuite E, Nielsen PE, Nordén B. Thermodynamics of sequence-specific binding of PNA to DNA. Biochemistry. 2000;39:7781–91. doi: 10.1021/bi000039g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang J, Rivas G, Cai X, Chicharro M, Parrado C, Dontha N, et al. Detection of point mutation in the p53 gene using a peptide nucleic acid biosensor. Anal Chim Acta. 1997;344:111–8. doi: 10.1016/S0003-2670(97)00039-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sato Y, Fujimoto K, Kawaguchi H. Detection of a K-ras point mutation employing peptide nucleic acid at the surface of a SPR biosensor. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2003;27:23–31. doi: 10.1016/S0927-7765(02)00027-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Corradini R, Feriotto G, Sforza S, Marchelli R, Gambari R. Enhanced recognition of cystic fibrosis W1282X DNA point mutation by chiral peptide nucleic acid probes by a surface plasmon resonance biosensor. J Mol Recognit. 2004;17:76–84. doi: 10.1002/jmr.646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sforza S, Galaverna G, Dossena A, Corradini R, Marchelli R. Role of chirality and optical purity in nucleic acid recognition by PNA and PNA analogs. Chirality. 2002;14:591–8. doi: 10.1002/chir.10087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Neilson PE, Haaima G. Peptide nucleic acid (PNA). A DNA mimic with a pseudopeptide backbone. Chem Soc Rev. 1997;26:73–8. doi: 10.1039/cs9972600073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rothenhausler B, Knoll W. Surface–plasmon microscopy. Nature. 1988;332:615–7. doi: 10.1038/332615a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ruemmele JA, Golden MS, Gao Y, Cornelius EM, Anderson ME, Postelnicu L, et al. Quantitative surface plasmon resonance imaging: a simple approach to automated angle scanning. Anal Chem. 2008;80:4752–6. doi: 10.1021/ac702544q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Homola J, Vaisocherová H, Dostálek J, Piliarik M. Multi-analyte surface plasmon resonance biosensing. Methods. 2005;37:26–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.D’Agata R, Grasso G, Iacono G, Spoto G, Vecchio G. Lectin recognition of a new SOD mimic bioconjugate studied with surface plasmon resonance imaging. Org Biomol Chem. 2006;4:610–2. doi: 10.1039/b517074e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.D’Agata R, Grasso G, Spoto G. Real-Time Binding Kinetics Monitored with Surface Plasmon Resonance Imaging in a Diffusion-Free Environment. The Open Spectroscopy Journal. 2008;2:1–9. doi: 10.2174/1874383800802010001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Grasso G, D'Agata R, Zanoli L, Spoto G. Microfluidic networks for surface plasmon resonance imaging real-time kinetics experiments. Microchem J. 2009;93:82–6. doi: 10.1016/j.microc.2009.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lockhart DJ, Winzeler EA. Genomics, gene expression and DNA arrays. Nature. 2000;405:827–36. doi: 10.1038/35015701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.He L, Musick MD, Nicewarner SR, Salinas FG, Benkovic SJ, Natan MJ, et al. Colloidal Au-Enhanced Surface Plasmon Resonance for Ultrasensitive Detection of DNA Hybridization. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:9071–7. doi: 10.1021/ja001215b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lee HJ, Wark AW, Corn RM. Creating advanced multifunctional biosensors with surface enzymatic transformations. Langmuir. 2006;22:5241–50. doi: 10.1021/la060223o. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Liu J, Tian S, Tiefenauer L, Nielsen PE, Knoll W. Simultaneously amplified electrochemical and surface plasmon optical detection of DNA hybridization based on ferrocene-streptavidin conjugates. Anal Chem. 2005;77:2756–61. doi: 10.1021/ac048088c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Spoto G, Corradini R, eds. Detection of non-amplified genomic DNA. Springer, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 86.D’Agata R, Corradini R, Grasso G, Marchelli R, Spoto G. Ultrasensitive detection of DNA by PNA and nanoparticle-enhanced surface plasmon resonance imaging. Chembiochem. 2008;9:2067–70. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200800310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zanoli L, D’Agata R, Spoto G. Surface plasmon-based optical detection of DNA by peptide nucleic acids. Minerva Biotec. 2008;20:165–74. [Google Scholar]

- 88.D’Agata R, Corradini R, Ferretti C, Zanoli L, Gatti M, Marchelli R, et al. Ultrasensitive detection of non-amplified genomic DNA by nanoparticle-enhanced surface plasmon resonance imaging. Biosens Bioelectron. 2010;25:2095–100. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.D’Agata R, Breveglieri G, Zanoli LM, Borgatti M, Spoto G, Gambari R. Direct detection of point mutations in nonamplified human genomic DNA. Anal Chem. 2011;83:8711–7. doi: 10.1021/ac2021932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Joung HA, Lee NR, Lee SK, Ahn J, Shin YB, Choi HS, et al. High sensitivity detection of 16s rRNA using peptide nucleic acid probes and a surface plasmon resonance biosensor. Anal Chim Acta. 2008;630:168–73. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Vester B, Wengel J. LNA (locked nucleic acid): high-affinity targeting of complementary RNA and DNA. Biochem. 2004;43:3233–13241. doi: 10.1021/bi0485732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Petersen M, Wengel J. LNA: a versatile tool for therapeutics and genomics. Trends Biotechnol. 2003;21:74–81. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7799(02)00038-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Natsume T, Ishikawa Y, Dedachi K, Tsukamoto T, Kurita N. Hybridization energies of double strands composed of DNA, RNA, PNA and LNA. Chem Phys Lett. 2007;434:133–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cplett.2006.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Demidov VV. PNA and LNA throw light on DNA. Trends Biotechnol. 2003;21:4–7. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7799(02)00008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–97. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Fang S, Lee HJ, Wark AW, Corn RM. Attomole microarray detection of microRNAs by nanoparticle-amplified SPR imaging measurements of surface polyadenylation reactions. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:14044–6. doi: 10.1021/ja065223p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Castoldi M, Schmidt S, Benes V, Noerholm M, Kulozik AE, Hentze MW, et al. A sensitive array for microRNA expression profiling (miChip) based on locked nucleic acids (LNA) RNA. 2006;12:913–20. doi: 10.1261/rna.2332406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kerremans L, Schepers G, Rozenski J, Busson R, Van Aerschot A, Herdewijn P. Hybridization between “six-membered” nucleic acids: RNA as a universal information system. Org Lett. 2001;3:4129–32. doi: 10.1021/ol016183r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Herdewijn P. Nucleic acids with a six-membered ‘carbohydrate’ mimic in the backbone. Chem Biodivers. 2010;7:1–59. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200900185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kolb G, Reigadas S, Boiziau C, van Aerschot A, Arzumanov A, Gait MJ, et al. Hexitol nucleic acid-containing aptamers are efficient ligands of HIV-1 TAR RNA. Biochemistry. 2005;44:2926–33. doi: 10.1021/bi048393s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Boder ET, Jiang W. Engineering antibodies for cancer therapy. Annu Rev Chem Biomol Eng. 2011;2:53–75. doi: 10.1146/annurev-chembioeng-061010-114142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.He J, Liu G, Vanderheyden JL, Dou S, Mary R, Hnatowich DJ. Affinity enhancement bivalent morpholino for pretargeting: initial evidence by surface plasmon resonance. Bioconjug Chem. 2005;16:338–45. doi: 10.1021/bc049719c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]