Abstract

Helicobacter pylori evade immune responses and achieve persistent colonization in the stomach. However, the mechanism by which H. pylori infections persist is not clear. In this study, we showed that MIR30B is upregulated during H. pylori infection of an AGS cell line and human gastric tissues. Upregulation of MIR30B benefited bacterial replication by compromising the process of autophagy during the H. pylori infection. As a potential mechanistic explanation for this observation, we demonstrate that MIR30B directly targets ATG12 and BECN1, which are important proteins involved in autophagy. These results suggest that compromise of autophagy by MIR30B allows intracellular H. pylori to evade autophagic clearance, thereby contributing to the persistence of H. pylori infections.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, MIR30B, ATG12, BECN1, autophagy

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is a gram-negative bacterium that plays an etiologic role in the development of gastritis, peptic ulceration and gastric adenocarcinoma.1 About half of the world’s population is infected with H. pylori, which is able to adapt and reside in the mucus, attach to epithelial cells, evade immune responses, and achieve persistent colonization in the stomach.2 Although H. pylori is generally considered as an extracellular microorganism, a growing body of evidence supports that at least a subset of H. pylori has an intraepithelial location and that a minor fraction of H. pylori resides inside gastric epithelial cells.3-5 The intracellular H. pylori fraction may represent the site of residence for persistent infection. Autophagy is a response by eukaryotic cells to a number of deleterious stimuli,6 and it plays a critical role in the regulation of survival of H. pylori. Recent studies suggest that autophagy functions as an innate immune response against H. pylori, decreasing its survival.7,8 Additionally, H. pylori can induce autophagy in gastric epithelial cells,5,8,9 but it still multiplies in these cells.9,10 The mechanism by which H. pylori antagonize host autophagy remains to be elucidated.

Single-stranded noncoding RNA molecules of 19–24 nucleotides, known as microRNAs (miRNAs), control gene expression at the post-transcriptional level,11 and their disruption is associated with human diseases.12,13 Accumulating evidence has demonstrated that miRNAs not only play a key regulatory role in the innate immune response to pathogens and stimuli,14-16 but also regulate autophagy.17-21 Previously, we used a miRNA microarray to detect the expression profiles of cellular miRNAs, and found that the expression level of MIR30B was significantly upregulated during H. pylori infection.22 To further explore the potential target proteins of MIR30B, we utilized the bioinformatic tool, Targetscan, and found that BECN1 and ATG12 were the main targets.

BECN1 (BCL2 interacting coiled-coil protein) is part of a Class-III PtdIns3K complex that participates in autophagosome formation, mediating the localization of other autophagy proteins to the preautophagosomal membrane.23 However, BCL2 anti-apoptotic protein inhibits BECN1-dependent autophagy.24 ATG12 (autophagy-related protein 12) contributes directly to the elongation of phagophores and the maturation of autophagosomes. In the ATG12 conjugation system, ATG12 is activated by ATG7, an E1-like enzyme, transferred to ATG10, an E2-like enzyme, and conjugated to ATG5 to form an ATG12-ATG5 conjugate.25 This conjugate functions as an E3-ligase complex to facilitate MAP1LC3B lipidation. Thus, BECN1 and ATG12 are both important proteins in regulating autophagy.

We hypothesized that MIR30B could downregulate BECN1 and ATG12 expression to compromise autophagy, resulting in increased H. pylori intracellular survival.

Results

Autophagy increases in AGS cell lines during H. pylori infection, but decreases in patients with chronic H. pylori infection

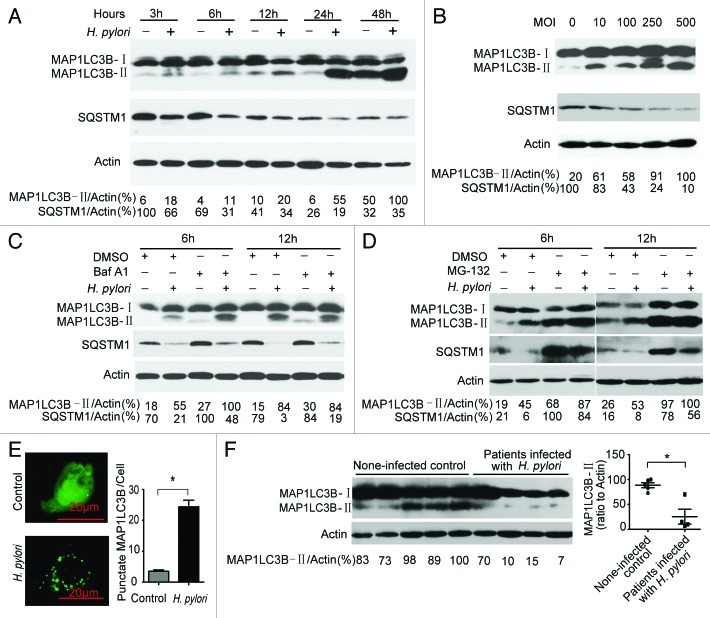

To determine whether autophagy could be induced during H. pylori infection, we investigated the ratio of MAP1LC3B-II to actin, which is considered as an accurate indicator for autophagy.26,27 We observed that there was a gradual increase over time in the ratio of MAP1LC3B-II to actin with H. pylori infection (MOI = 100:1) as compared with an uninfected control. In addition, by measuring SQSTM1 degradation, we observed a gradual decline in SQSTM1 protein levels upon H. pylori infection (Fig. 1A). Be consistent with the observed MAP1LC3B-II ratios and SQSTM1 degradation in time-course experiments, similar results were observed when testing dose dependency in AGS and BGC-823 cells (Fig. 1B; Fig. S1). Furthermore, Baf A1 challenge resulted in further accumulation of MAP1LC3B-II and SQSTM1 in AGS cells after 6 h of infection (Fig. 1C), suggesting that H. pylori infection promote cellular autophagic processes. However, the concentration of SQSTM1 remains decreased in the presence of Baf A1. One possibility is that the concentration of Baf A1 used did not totally block the degradative step of autophagy. Furthermore, AGS cells were challenged with MG-132 (a proteasome inhibitor). MG-132 challenge resulted in further accumulation of MAP1LC3B-II and SQSTM1 in AGS cells (Fig. 1D), suggesting that the proteasome can degrade MAP1LC3B-II and SQSTM1 during H. pylori infection, or MG-132 can induce autophagy in AGS cells. To further confirm that H. pylori induce autophagy in AGS cells, we used a GFP-MAP1LC3B puncta formation assay for monitoring autophagy. H. pylori-infected AGS cells displayed a significant increase in the percentage of cells with autophagosomes (GFP-MAP1LC3B dots) after 6 h compared with mock-infected AGS cells (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1E). These data indicate that a complete autophagic response is induced in an AGS cell line infected with H. pylori.28

Figure 1. Autophagy is induced after H. pylori infection, but it was decreased in patients with chronic H. pylori infection. (A and B) H. pylori increased the conversion of MAP1LC3B-I to MAP1LC3B-II in AGS cells. AGS cells were treated with H. pylori (MOI = 100:1) for 3, 6, 12, 24 and 48 h and treated with H. pylori at MOI = 0, 10, 100, 250 and 500 for 6 h. (C) H. pylori induced incomplete autophagic flux in AGS cells. AGS cells were treated with H. pylori (MOI = 100:1) for 6 h in the presence of Baf A1 (10 nM). (D) AGS cells were treated with H. pylori (MOI = 100:1) for 6 h in the presence of MG-132 (10 μM). (E) AGS cells were transfected with a plasmid expressing GFP-MAP1LC3B. After 24 h, the cells were incubated for 6 h at 37°C in F12 medium with H. pylori. Following fixation, cells were immediately visualized by confocal microscopy. The number of GFP-MAP1LC3B puncta in each cell was counted. (F) The conversion of MAP1LC3B-I to MAP1LC3B-II in gastric mucosal tissues from H. pylori-positive patients (n = 4) was lower than its expression in H. pylori-negative individuals (n = 5). Experiments performed in triplicate showed consistent results. Compared with controls, *p < 0.05.

In view of the fact that the infection of H. pylori persists throughout life unless specifically treated,29 the results from the cell model may not well explain the mechanism of disease. Thus, the conversion of MAP1LC3B-I to MAP1LC3B-II in gastric mucosal tissues from H. pylori-positive patients and noninfected individuals was detected. As shown in Figure 1F, autophagy decreases in patients with chronic H. pylori infection compared with noninfected individuals. The exact molecular mechanism underlying this phenomenon remains to be fully elucidated.

Inhibition of autophagy increases intracellular survival of H. pylori in AGS cells

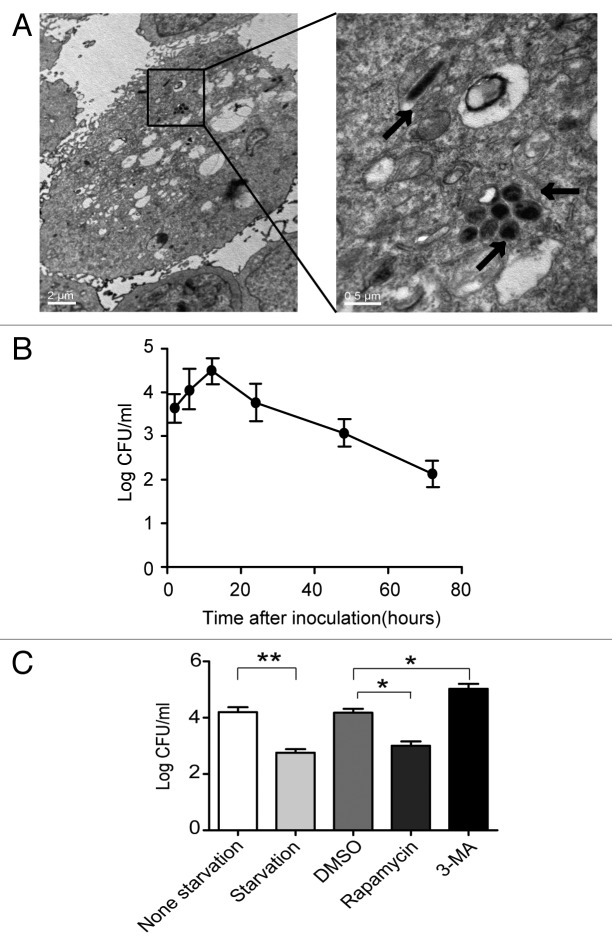

Previous studies indicated that H. pylori invaded gastric epithelial cells.28,30-32 In this study, using transmission electron microscopy (TEM), we showed that H. pylori invades AGS cells (Fig. 2A). To evaluate the number of live internalized H. pylori cells in AGS cells, a gentamicin protection assay was used. The number of colony forming units (CFU) of H. pylori after 12 h of infection was increased at least 10-fold compared with 3 h of infection, indicating that internalized H. pylori underwent replication; CFU then decreased after 12 h (Fig. 2B). To determine whether H. pylori-induced autophagy could eliminate intracellular bacteria, the effect of autophagy on intracellular survival of H. pylori was examined by exposing the cells to an autophagy inhibitor (3-methyladenine, 3-MA) or autophagy activators (starvation, or Rapamycin). A significant increase in the intracellular H. pylori population was observed in AGS cells after inhibition of autophagy (3-MA), and a decrease was also observed with inducers of autophagy (Rapamycin and starvation)(Fig. 2C). At all time points during a 72-h experiment, it was observed that the number of intracellular H. pylori cells in the 3-MA group was elevated compared with the other groups (Fig. S2). These findings indicate that inhibition of autophagy increases the intracellular survival of H. pylori in AGS cells.

Figure 2. Autophagy inhibition increases multiplication of H. pylori in AGS cells. (A) Representative TEM images of AGS cells after 6 h infection with H. pylori 26695 (MOI = 100:1). Arrows indicate digested bacteria. (B) Multiplication of H. pylori in AGS cells. AGS cells infected with H. pylori (MOI = 100:1) for 3, 6, 12, 24, 48 and 72 h were lysed, and intracellular bacteria were quantified after inoculation. The recovered viable H. pylori were determined as CFU on a CDC anaerobic blood agar plate. (C) The effects of starvation, 3-MA or rapamycin on the multiplication of H. pylori in AGS cells. After pretreatment by starvation, DMSO, rapamycin (100 nM), or 3-MA (2 mM), AGS cells were infected with H. pylori 26695 (MOI = 100:1) for 6 h and then lysed. Intracellular bacteria were quantified after inoculation. *p < 0.05 by Student’s t-test. Results shown are representative of five independent experiments.

MIR30B is upregulated after H. pylori infection

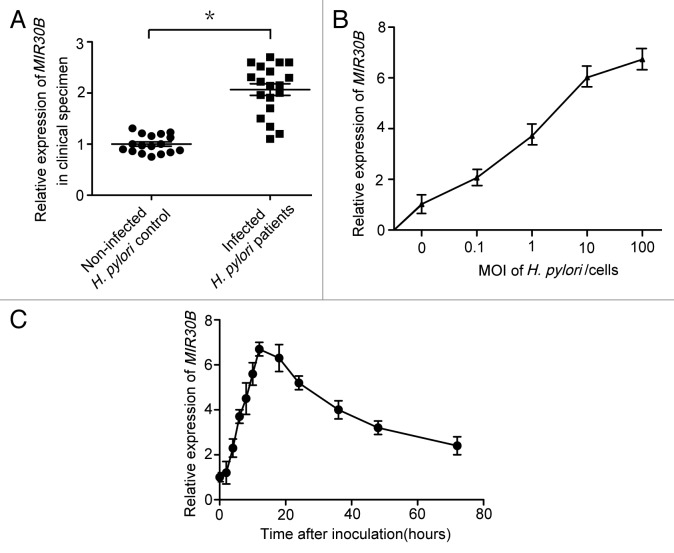

To confirm the validity of the microarray data, expression of MIR30B was examined in gastric mucosal tissues infected with H. pylori. A significant increase in MIR30B expression was observed in patients infected with H. pylori (p < 0.05 vs. H. pylori–negative persons) (Fig. 3A); MIR30A was not increased in these samples (Fig. S3A). In addition, in gastric epithelial cell lines (AGS, SGC-7901, BGC-823 or HGC-27) infected with H. pylori 26695 at different MOI for 6 h, increased expression of MIR30B was observed in every cell line but BGC-823 (Fig. S4), with AGS cells showing the greatest increase (Fig. 3B). We did not find increased expression of MIR30A in AGS cell lines (Fig. S3B). To monitor the kinetics of MIR30B induction, mature MIR30B was detected over a period of 72 h following H. pylori infection in AGS cells. During H. pylori infection, the expression of MIR30B rapidly increased from 2 to 12 h of infection, reached the highest levels at 12 h, then decreased slowly from 12–72 h (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, there was no effect on expression of MIR30B during infection by other pathogens (E. coli DH5α and O157:H7) or in the presence of autophagy inducer (Rapamycin) and inhibitor (3-MA) (Fig. S5). Collectively, the results above suggest that expression of MIR30B is increased upon H. pylori infection.

Figure 3. MIR30B is upregulated in response to H. pylori infection. (A) Expression of MIR30B in gastric mucosal tissues from H. pylori-positive patients (n = 19) was higher than its expression in H. pylori-negative, healthy individuals (n = 17). (B) Real-time PCR detection of MIR30B at indicated MOI after infection of AGS cell lines with H. pylori for 12 h. (C) The kinetics of MIR30B induction assayed by qRT-PCR at different time points (0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 18, 24, 36, 48 and 72 h) after H. pylori stimulation of AGS cells (MOI = 100). Data are representative of five independent experiments. *p < 0.05 via Student’s t-test.

MIR30B downregulates autophagy after H. pylori infection

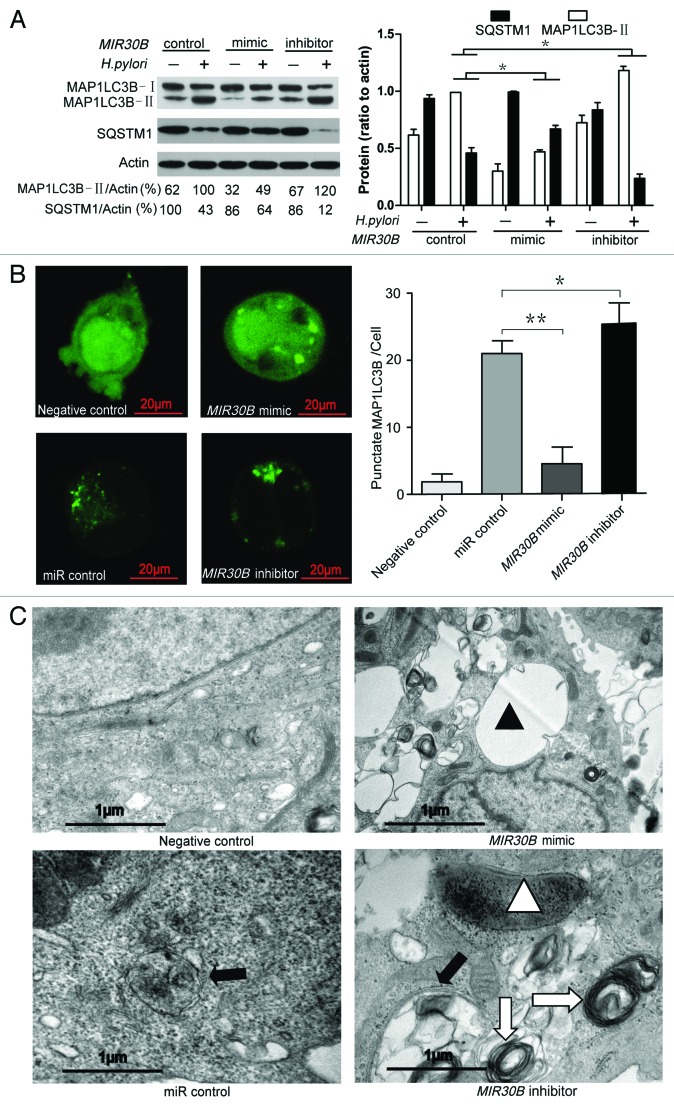

To provide evidence that MIR30B has a role in the negative regulation of autophagy during H. pylori infection, we examined the effect of MIR30B on the expression of MAP1LC3B-II and SQSTM1 in AGS cells upon H. pylori infection. A MIR30B mimic significantly attenuated MAP1LC3B-II conversion and SQSTM1 degradation, while a MIR30B inhibitor increased them (Fig. 4A). To determine whether the effect of MIR30B on autophagy is specific to H. pylori, we detected MAP1LC3B-II conversion under starvation conditions. As shown in Figure S6, MIR30B compromised autophagy in the presence of starvation. Furthermore, co-transfection of a GFP-MAP1LC3B vector and a MIR30B mimic significantly decreased formation of GFP-MAP1LC3B dots in AGS cells upon H. pylori infection (Fig. 4B). TEM of AGS cells transfected with MIR30B mimic revealed a decrease in the number of autophagosomes and autolysosomes after 12 h of infection with H. pylori, and there were numerous large vacuoles induced by H. pylori VacA in the MIR30B mimic group but not in the control groups. In the MIR30B inhibitor group, the onion-like structure of multiple-layer vesicles, which are recognized as an indicator of enhanced autophagy,8 was observed more often than in the other groups (Fig. 4C). To examine whether VacA-dependent vacuoles are dependent on MIR30B, we examined the vacuoles in H. pylori-infected cells after transfection of MIR30B control, mimic or inhibitor. As shown in Figure S7, MIR30B mimic increased the number of VacA-dependent vacuoles in H. pylori-infected cells. These data indicate that MIR30B compromises autophagy during H. pylori infection and leads to formation of VacA-dependent large vacuoles.

Figure 4. MIR30B downregulates autophagy in H. pylori infection. (A) Measurement of MAP1LC3B-II conversion and SQSTM1 degradation with overexpression of MIR30B by western blot assay. AGS cells were transfected with MIR30B control (100 nM), mimic (100 nM) or inhibitor (100 nM) for 24 h and infected with H. pylori for an additional 24 h. Cell lysates were prepared and analyzed. (B) Quantification of GFP-MAP1LC3B puncta (autophagosomes). AGS cells were co-transfected with GFP-MAP1LC3B plasmid and MIR30B control, mimic or inhibitor for 24 h, and were then infected with H. pylori for an additional 6 h. The number of punctate GFP-MAP1LC3B spots in each cell was counted. (C) Ultrastructural alterations in H. pylori-infected AGS cells after transfection with MIR30B control, mimic or inhibitor for 24 h. Infected cells were collected for TEM examination. Negative control shows the mock samples without H. pylori infection. Closed triangles indicate VacA-dependent large vacuoles whereas open triangles show digested bacteria. Closed arrow indicates autophagosomes whereas open arrow shows the multilayer vesicular structure. The asterisks denote significant differences from control (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01). Experiments performed in triplicate showed consistent results.

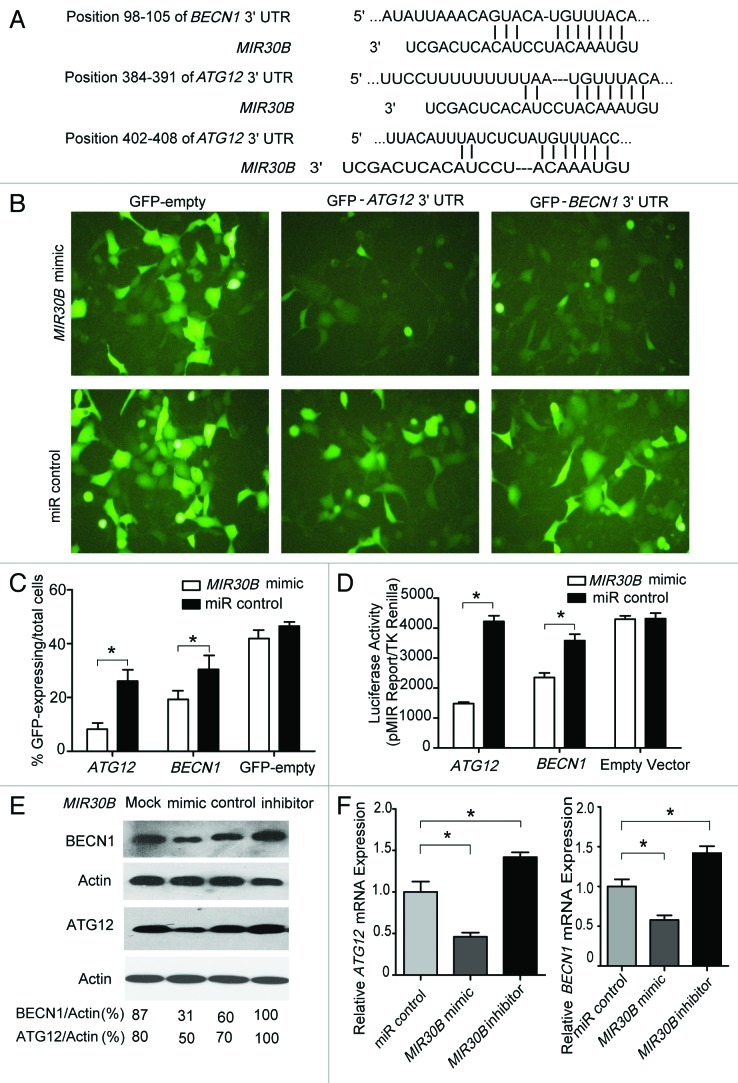

ATG12 and BECN1 are novel targets of MIR30B

In a screen for MIR30B targets, ATG12 and BECN1 were identified as putative MIR30B target genes by using TargetScan (version 4.2, www.targetscan.org) (Fig. 5A). To directly address whether MIR30B binds to the 3′UTR of target mRNAs, we generated two GFP reporter vectors containing the putative MIR30B binding sites within the 3′UTRs of ATG12 and BECN1. GFP fluorescence was significantly reduced in cells co-transfected with MIR30B mimic and binding site-containing GFP reporter vectors, while no obvious reduction of GFP fluorescence was observed in cells transfected with miR control or with GFP reporters lacking binding sites (Fig. 5B). Similar results were also observed with flow cytometry (Fig. 5C and Fig. S8). Furthermore, two luciferase reporter vectors were generated that contain the putative MIR30B binding sites within their 3′UTRs. Consistent with the GFP reporter results, the relative luciferase activity was reduced by 70% (3′UTR of ATG12) or 40% (3′UTR of BECN1) following co-transfection with the MIR30B mimic compared with co-transfection with the miR control. In contrast, no change in luciferase activity was observed in cells transfected with reporters lacking binding sites or with the miR control (Fig. 5D). The above results suggest that MIR30B targets the predicted site in the ATG12 and BECN1 genes. To validate the functional inhibition of the two target genes by MIR30B, a MIR30B mimic was transfected into AGS cells, and subsequently the production of the two proteins was detected by western blot. We observed that the production of the two proteins was decreased with the MIR30B mimic as compared with the miR control or mock transfection (Fig. 5E). Because miRNAs may downregulate their target genes through mRNA degradation or translation inhibition, we tried to determine which mechanism is responsible for suppression of the two genes by MIR30B. We measured the mRNA levels of each gene in AGS cells transfected with the MIR30B control, mimic, or inhibitor. Consistent with the western blot results, the mRNA levels of the two genes showed a 50% reduction with the MIR30B mimic (Fig. 5F). Thus, MIR30B may downregulate ATG12 and BECN1 expression through mRNA degradation.

Figure 5. ATG12 and BECN1 are novel targets of MIR30B. (A) The region of the human ATG12 and BECN1 mRNA 3′UTR predicted to be targeted by MIR30B (TargetScan 4.2). (B and C) Representative fluorescent microscopic image and flow cytometry results demonstrate that GFP expression of the GFP-ATG12 and BECN1 reporters was inhibited by MIR30B. HEK-293 cells were co-transfected with the GFP reporter vectors and compared with cells transfected with a mimic or control of MIR30B. (D) Luciferase reporter assay. HEK293 cells were transiently co-transfected with luciferase reporter vectors and either MIR30B mimic or control. Luciferase activity was normalized to the activity of Renilla luciferase. (E and F) AGS cells were transiently transfected with MIR30B mimic, inhibitor or control for 24 h. The mRNA and protein levels of BECN1 and ATG12 were determined by qRT-PCR and western blot. Data are representative of five independent experiments (* p < 0.05).

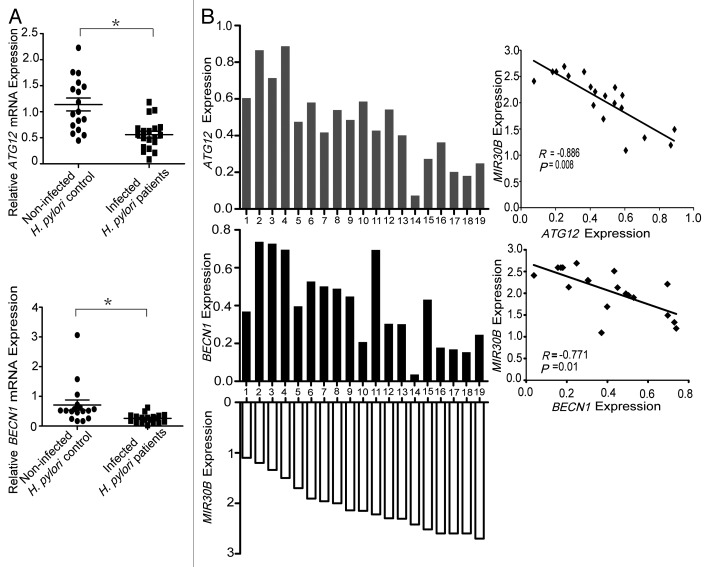

Inverse correlation between MIR30B and ATG12/BECN1 expression in H. pylori-positive human samples

In order to address the biological significance of the interaction between ATG12/BECN1 and MIR30B in H. pylori infections, we initially examined their expression in the human gastric tissues used in this study. We found that the mRNA levels of ATG12/BECN1 were markedly inhibited in H. pylori-positive human samples, compared with normal tissues (Fig. 6A). We speculated that the reduced ATG12/BECN1 expression in human samples could be a result of elevated MIR30B expression. Therefore, Spearman correlation analysis was used to compare the relative expression levels of ATG12/BECN1 and MIR30B in human clinical specimens. We obtained two statistically significant inverse correlations from a total of 19 H. pylori-positive gastric tissues (ATG12/MIR30B, R = -0.886, p = 0.008; BECN1/MIR30B, R = -0.771, p = 0.01) (Fig. 6B), indicating that MIR30B expression is inversely correlated with ATG12/BECN1 in human samples.

Figure 6. Inverse correlation between MIR30B and BECN1/ATG12 expression in H. pylori-positive human samples. (A) BECN1/ATG12 and MIR30B expression levels are inversely correlated in human samples. BECN1 and ATG12 mRNA expression in gastric mucosal tissues from H. pylori-positive patients (n = 19) were lower than those of H. pylori-negative individuals (n = 17). (*p < 0.05) (B) The inverse correlation between BECN1/ATG12 and MIR30B expression levels was examined by Spearman correlation analysis (BECN1/MIR30B, R = -0.771, p = 0.01; ATG12/MIR30B, R = -0.886, p = 0.008).

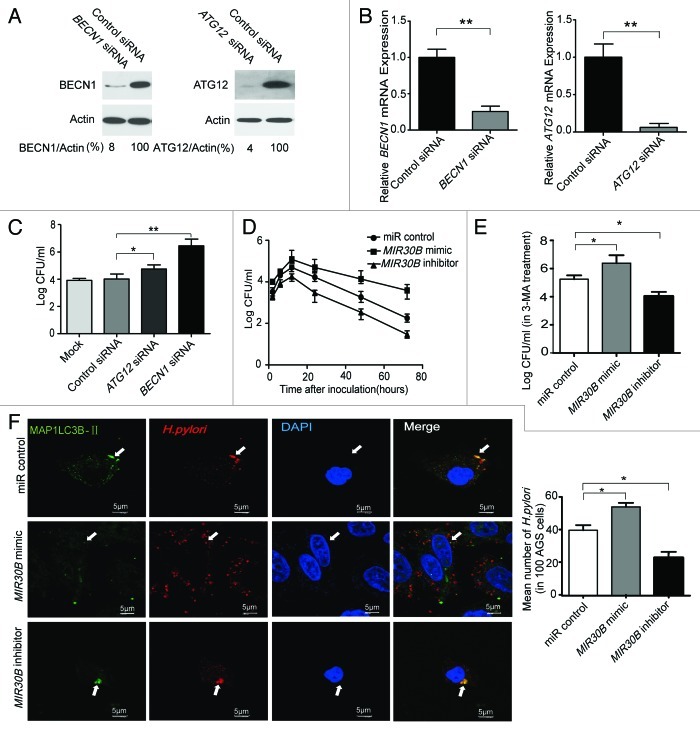

MIR30B increases the intracellular survival of H. pylori.

We used siRNAs of target genes and the MIR30B mimic to measure the intracellular H. pylori survival ratio in AGS cells after 6 h infection. We found that the mRNA and protein levels of ATG12 and BECN1 were significantly decreased in AGS cells transfected with siRNAs (Fig. 7A and 7B). Furthermore, ATG12 and BECN1 silencing resulted in drastically increased intracellular survival of H. pylori in AGS cells (p < 0.05, or 0.001 vs. noncoding siRNA control) (Fig. 7C). Moreover, we examined intracellular survival of H. pylori in AGS cells at different time points after infection in the presence of MIR30B control, mimic or inhibitor. After H. pylori infection, the intracellular H. pylori population rapidly increased, reached its highest level at 12 h, and slowly decreased from 12–72 h (Fig. 7D). A similar effect was observed in AGS cells with enforced expression of MIR30A (Fig. S3C). To further confirm that MIR30B can modulate the intracellular survival of H. pylori, we detected the effect of MIR30B on bacterial survival under autophagy inhibition conditions. As shown in Figure 7E, MIR30B increased intracellular survival of H. pylori in cells treated with 3-MA. Moreover, to obtain further experimental evidence for the possibility, we examined the conversion of MAP1LC3B-I to MAP1LC3B-II with 3-MA and MIR30B treatment in H. pylori infection, as shown in Figure S10. 3-MA (2 mM) could not completely inhibit autophagy. In addition, as shown in Figure 7F by confocal microscopy, H. pylori resided and multiplied in the cytoplasm, but only a small fraction of them colocalized with autophagosomes. Moreover, there were more intracellular H. pylori cells in the MIR30B mimic group than in the other treatment groups. Together, these data suggest that MIR30B increases the intracellular survival ratio of H. pylori in AGS cells.

Figure 7. MIR30B increases the intracellular survival ratio of H. pylori. (A and B) Detection of inhibition efficiency of siRNAs against BECN1 and ATG12. AGS cells were transfected with two siRNAs targeting BECN1 and ATG12 (100 nM) for 24 h, and mRNA and protein levels of the two genes were determined by qRT-PCR and western blot. (C) Gentamicin protection assay of the intracellular survival ratio of H. pylori with siRNAs against BECN1 and ATG12. AGS cells were transfected with BECN1, ATG12 or a control siRNA at 100 nM for 24 h followed by infection with H. pylori. (D) AGS cells were transfected with MIR30B control, mimic or inhibitor at 100 nM for 24 h, and were then infected with H. pylori for different periods of time (0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 18, 24, 36, 48 and 72 h). Intracellular bacterial counts were determined by gentamicin protection assay. (E) After AGS cells were transfected with MIR30B control, mimic or inhibitor, and pretreated by 3-MA for 24 h, intracellular survival of H. pylori was detected by gentamicin protection assay. (F) H. pylori infection in AGS cells induces GFP-MAP1LC3B puncta formation around the bacteria. AGS cells were transfected by MIR30B control, mimic or inhibitor for 24 h, followed by H. pylori infection for 6 h. The extracellular bacteria were killed with gentamicin. The infected AGS cells were stained with anti-H. pylori antibodies (red) and DAPI (blue). The arrow indicates the presence of H. pylori cells. Data are representative of five independent experiments (*p < 0.05).

Discussion

Based on the present results, we proposed that compromise of autophagy by MIR30B benefits the intracellular H. pylori to evade autophagic clearance through targeting BECN1 and ATG12. The novel model is supported by the following data: (1) autophagy decreased in patients with chronic H. pylori infection, (2) MIR30B was upregulated during H. pylori infection in AGS cell line and human gastric tissues, and (3) compromised autophagy by MIR30B benefited bacterial replication through targeting BECN1 and ATG12 during the H. pylori infection.

It is becoming increasingly recognized that altered autophagy is associated with persistent bacterial infection. For example, Yen-Ting Chu et al. have reported that the autophagy inducer rapamycin enhances the clearance of the H. pylori.33 They have also reported that H. pylori usurp the autophagic vesicles as the site for replication, and the autolysosomes after fusion will also degrade the replicating bacteria.33 Therefore, compromised autophagy may benefit the intracellular survival of H. pylori. Our findings may provide a novel mechanism for elucidating persistent H. pylori infection. The compromised autophagy by MIR30B results in a failure to eliminate the intracellular H. pylori, leading to persistent infection and proliferation of H. pylori in the host cells.

In our study, H. pylori infection increased MIR30B during in vivo and in vitro infections, but there were inconsistent results of autophagy in the two settings. These different results suggest that H. pylori-mediated autophagic processes may be complex.28 Autophagy plays specific roles in shaping immune system development, fueling host innate and adaptive immune responses, and directly controlling the survival of intracellular microbes as a cell-autonomous innate defense.34 To resist autophagic clearance, intracellular pathogens have evolved to block autophagic microbicidal defense and subvert host autophagic responses for their survival or growth.34 In our cell model, although overexpression of MIR30B could decrease autophagy through inhibiting the expression of ATG12 and BECN1 (Fig. 5E), this adjusting process may lag behind autophagy induced by H. pylori. Moreover, the part of downregulated autophagy by MIR30B may be not sufficient to block autophagy induced by H. pylori. In the study, although MIR30B mimic was added exogenously, autophagy in H. pylori infection was still more than that in uninfected group (Fig. 4A). Thus, in spite of overexpression of MIR30B, autophagy still increased during in vitro infection. Given the complexity of H. pylori in vivo infection, many factors may be involved in autophagy inhibition. As one of the factors, overexpression of MIR30B may slightly continue to compromise the expression of ATG12 and BECN1 for a long time, leading to subverting host autophagic responses for their survival or growth.

It is of note that upon stimulation with H. pylori infection, miR-30 family members showed a differential response in which MIR30B was upregulated whereas MIR30A was not significantly altered. Although miR-30 family members have a similar sequence, they are expressed by genes localized in different chromosomes.35 It is possible that differential stimuli may affect different genes expression.

Recently, miRNAs have been indicated to play a key role in the regulation of autophagy, such as: MIR30A, MIR17/20/93/106, MIR204, MIR10B.17-19,21 MIR30A was reported to regulate autophagy molecule by targeting BECN1.17 In addition, MIR17/20/93/106 promote hematopoietic cell expansion by targeting sequestosome 1-regulated pathways in mice,18 and MIR204 regulates cardiomyocyte autophagy induced by ischemia-reperfusion through MAP1LC3B-II.19 In this report, we found that MIR30B is a novel regulator of autophagy by targeting BECN1 and ATG12, which are key autophagy-promoting proteins.

To date, about 10 genes have been experimentally validated in predicted targets of MIR30B, including CTGF (connective tissue growth factor), UBE2I (ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2I), ITGB3 (Integrin b3) and TP53 et al.35-41 For example, MIR30B can interact with 3′UTR of EED and regulate endogenous EED expression in neural tissues.42 LHX1, a major transcriptional regulator of kidney development, was also targeted by MIR30B.43 Here, we identified BECN1 and ATG12, which are important genes in regulating autophagy, as novel targets of MIR30B.

In summary, our findings provide a novel mechanism in which compromised autophagy by MIR30B benefits the intracellular survival of H. pylori. In addition, these results open a new avenue of research on the potential of miRNAs to modulate autophagy by regulating the expression of key autophagy genes such as BECN1 and ATG12. Although the mechanism of H. pylori infection persistence remains to be determined, this study establishes a basis necessary for future evaluation of the role of MIR30B in H. pylori infections.

Materials and Methods

Antibodies and reagents

The GFP-MAP1LC3B plasmid was kindly provided by Dr. Tamotsu Yoshimori (Department of Cell Biology, National Institute for Basic Biology, Presto, Japan). 3-methyladenine (3-MA, M9281), bafilomycin A1 (Baf A1, B1793) rapamycin (Rapa, R8781) and MG-132 (C2211) were purchased from Sigma; antibodies against MAP1LC3B (L7543) and ATG12 (WH0009140m1) were obtained from Sigma. Antibody against BECN1 (612112) was obtained from BD Transduction Laboratories, Inc. whereas antibodies against Actin (sc-10731) and SQSTM1 (sc-28359) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology.

Cell lines and H. pylori strains

Human gastric cancer cell lines AGS and HGC 27 were separately cultured in F12 (Gibco, 11765-054) and DMEM media (Gibco, 11965-092) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, 10099-141) and 100 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco, 15140-122) in a humidified incubator containing 5% CO2 at 37°C. The three additional cell lines SGC7901, BGC823 and human embryonic kidney HEK-293 cells were routinely cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, 11875-093) supplemented with 10% FBS and penicillin/streptomycin. The wild-type H. pylori strain 26695 (700392) was obtained from ATCC and grown as previously described.44

Patients and gastric mucosal specimens

In total, 45 patients undergoing gastroscopic examination at Xinqiao Hospital and Southwest Hospital were included in the study. The patients included 23 individuals with H. pylori-induced chronic gastritis (median age, 44 y [range, 25–60 y]; 13 women, 10 men) and 22 H. pylori-negative control subjects (median age, 32 y [range, 26–55 y]; 14 women, 8 men). The H. pylori infection status was confirmed by bacterial culture, C13-urea breath test and histologic testing. Patients were regarded as being H. pylori-positive if one or more tests yielded positive results. None of the patients received nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and none had taken antibiotics or proton pump inhibitor drugs in the preceding four weeks. The study was approved by the ethics review board at Third Military Medical University, and informed consent was obtained from all patients before participation. Histological assessment was performed according to the Sydney classification by two pathologists who were blinded to the other experimental results.

Plasmid construction

The construction of luciferase reporter vectors and GFP reporter vectors for the MIR30B targets ATG12 and BECN1 was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The 3′UTRs of BECN1 (439 bp) and ATG12 (427 bp) were amplified using cDNA from AGS cells (primers for BECN1: forward-5′-ACTAGTAGGGGGAGGTTTG-3′, reverse-5′-AAAGCTTAGATGTCA-3′; primers for ATG12: forward-5′-ACTAGTAACTTGCTACTACA-3′, reverse-5′-AAGCTTCA GCCAGCAGGTCAAT-3′), and digested by the SpeI (Takara, D1086) and HindIII (Takara, D1060) restriction enzyme, and ligated into the multiple cloning site of the pMIR-REPORT™ luciferase vector (Ambion, AM5795). The resulting constructs were named pMIR-BECN1-wt and pMIR-ATG12-wt. To construct a GFP reporter for microRNAs, the luciferase-encoding sequences in the pMIR-REPORT™ vector were replaced with the GFP-encoding sequence from pEGFP-N1 (Clontech, 60851) using BamHI (Takara, D1010) and SpeI restriction sites; the resulting plasmid was named pMIR-GFP-REPORT. The putative MIR30B target sites of BECN1 and ATG12 were inserted into the reconstructed GFP reporter vector as described.

Luciferase assay and GFP repression experiments

HEK-293 cells were transfected with 0.8 μg of firefly luciferase reporter vector (pMIR-BECN1-wt or pMIR-ATG12-wt), 100 nM MIR30B mimic (Ambion, 4464066) or control (Ambion, 4464058), and 0.04 μg of Renilla luciferase control vector (pRL-TK-Promega, 2241) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, 11668019). Assays were performed 24 h after transfection using the dual luciferase reporter assay system (Promega, E1910). Firefly luciferase activity was normalized to Renilla luciferase activity. For GFP repression experiments, HEK-293 cells were co-transfected with the indicated MIR30B mimic or control (100 nM) along with pMIR-GFP-BECN1-wt or pMIR-GFP-ATG12-wt. Pictures were taken 24 h after transfection using an Olympus microscope (IX71).

Quantitative RT-PCR

Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) analyses for MIR30A/B were performed by using TaqMan miRNA assays (Ambion, 4440886) in a Bio-Rad IQ5 (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). The reactions were performed using the following parameters: 95°C for 2 min followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 30 sec. RNU6-1 small nuclear RNA was used as an endogenous control for data normalization. Relative expression was calculated using the comparative threshold cycle method. The results represented at least 3 separate experiments performed in triplicate.

Quantitative RT-PCR analyses for the mRNA of ATG12 and BECN1 were performed by using PrimeScript RT-PCR kits (Takara, DRR037). The mRNA level of ACTB was used as an internal control. The primer sequences are as follows: BECN1, forward-5′-CTGAGGGATGGAAGGGTC-3′, reverse-5′-TGGGCTGTGGTAAGTAATG-3′; ATG12, forward-5′-AGTAGAGCGAACACGAACCATCC-3′, reverse-5′-AAGGAGCAAAGGACTGATTCACATA-3′; ACTB forward-5′-TTCCTTCCTGGGCATGGAGTCC-3′, reverse-5′-TGGCGTACAGGTCT TTGCGG-3′.

siRNA assay

The ATG12 (human, sc-72578) and BECN1 siRNAs (human, sc-29797) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology along with control siRNA (sc-44230). All siRNA transfections were performed with Dharmafect 1 transfection reagent (Thermo Scientific, T-2001-03). AGS cells were transfected with 100 nM siRNA for 48 h, followed by H. pylori infection; protein and mRNA knockdown were assessed by western blot analysis and qRT-PCR, respectively.

Transmission electron microscopy

AGS cells were collected and fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde, 0.1% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate for 2 h, postfixed with 1% OsO4 for 1.5 h, washed and stained for 1 h in 3% aqueous uranyl acetate. The samples were then washed again, dehydrated with graded alcohol and embedded in Epon-Araldite resin (Canemco, 034). Ultrathin sections were cut on a Reichert ultramicrotome, counterstained with 0.3% lead citrate and examined on a Philips EM420 electron microscope.

Confocal microscopy

AGS cells were co-transfected with the indicated MIR30B mimics, inhibitors (Ambion, 4464084) or control (100 nM) along with the GFP-MAP1LC3B-expressing plasmid; after 24 h, cells were infected with H. pylori for 6 h. After infection, cells were washed with PBS, fixed by incubation for 10 min at 37°C in 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 and washed with PBS containing 2% BSA. Permeabilized cells were incubated for 1 h with primary antibody at room temperature, washed extensively with PBS buffer, and incubated for 1 h with secondary antibody. All steps were performed at room temperature. The primary antibody used was rabbit anti-H. pylori (DAKO, B0471), and the secondary antibody was Alexa Fluor 555-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (Beyotime, P0178). After staining, we mounted coverslips using Vectashield (Vector Laboratories, H1200). We used a Radiance 2000 laser scanning confocal microscope for confocal microscopy followed by analysis with LaserSharp 2000 software (Bio-Rad). We acquired images in sequential scanning mode.

Gentamicin protection assay

After infection, the AGS-bacterium co-culture was washed three times with 1 ml of warm PBS per well to remove nonadherent bacteria. To determine the CFU count corresponding to intracellular bacteria, the AGS cell monolayers were treated with gentamicin (100μg/ml; Sigma, G1272) at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 1 h, washed three times with warm PBS, and then incubated with 1 ml of 0.5% saponin (Sigma, 47036) in PBS at 37°C for 15 min. The treated monolayers were resuspended thoroughly, diluted and plated on serum agar. To determine the total CFU corresponding to host-associated bacteria, the infected monolayers were incubated with 1 ml of 0.5% saponin in PBS at 37°C for 15 min without prior treatment with gentamicin. The resulting suspensions were diluted and plated as described above. Both the CFU of intracellular bacteria and the total CFU of cell-associated bacteria are given as CFU per well of AGS cells.

Western blot

Cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and then lysed in Triton X-100/glycerol buffer (50 mM TRIS-HCl, 4 mM EDTA, 2 mM EGTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 25% wt/vol sucrose, pH 8.0, supplemented with 1% Triton X-100 and protease inhibitor). After centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C, the protein concentration was measured with a BCA protein assay kit (Pierce, 23227). Lysates were separated using SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. The membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline, pH 7.4, containing 0.05% Tween 20 (Sigma, P1379), and were incubated with primary anti-human antibodies and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary anti-mouse antibodies (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, 115-035-003) or anti-rabbit antibodies (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, 111-035-003) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The protein of interest was visualized using Supersignal® West Dura Duration substrate reagent (Thermo, 34080).

Flow cytometry

HEK293 cells were co-transfected with pMIR-GFP-ATG12 plasmids or pMIR-GFP-BECN1 plasmids together with MIR30B control or mimics. HEK293 cells, used as a blank control, were not transfected. At 24 h post-transfection, cells were subjected to flow cytometric analysis on a FACSCalibur, and data were analyzed with CellQuest software (both from BD Biosciences). The results presented herein were compiled from three independent experiments.

Statistical analysis

The results are expressed as mean ± SD from at least 3 separate experiments performed in triplicate. The differences between groups were determined with a two-tailed Student’s t-test using SPSS 11.5 software. Statistical differences were declared significant at p < 0.05. Statistically significant data are indicated by asterisks (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Jiqing Lian, Dr. Fengjun Wang and Zhao Yang for critical reading and editing of the manuscript. We also thank Dr. Tamotsu Yoshimori for providing the GFP-MAP1LC3B plasmid. This study was supported by a grant from National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC, No. 81071412).

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- H. pylori

Helicobacter pylori

- 3-MA

3-methyladenine

- miRNAs

microRNAs

- TEM

transmission electron microscopy

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- MAP1LC3B

microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 beta

- FACS

flow cytometry

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- SQSTM1

sequestosome 1

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Supplemental Materials

Supplemental materials may be found here: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/autophagy/article/20159

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/autophagy/article/20159

References

- 1.Suerbaum S, Michetti P. Helicobacter pylori infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1175–86. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Acheson DW, Luccioli S. Microbial-gut interactions in health and disease. Mucosal immune responses. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;18:387–404. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petersen AM, Krogfelt KA. Helicobacter pylori: an invading microorganism? A review. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2003;36:117–26. doi: 10.1016/S0928-8244(03)00020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang YH, Wu JJ, Lei HY. When Helicobacter pylori invades and replicates in the cells. Autophagy. 2009;5:540–2. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.4.8167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Terebiznik MR, Vazquez CL, Torbicki K, Banks D, Wang T, Hong W, et al. Helicobacter pylori VacA toxin promotes bacterial intracellular survival in gastric epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 2006;74:6599–614. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01085-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levine B, Kroemer G. Autophagy in the pathogenesis of disease. Cell. 2008;132:27–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang JC, Chien CT. A new approach for the prevention and treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection via upregulation of autophagy and downregulation of apoptosis. Autophagy. 2009;5:413–4. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.3.7826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang YH, Wu JJ, Lei HY. The autophagic induction in Helicobacter pylori-infected macrophage. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2009;234:171–80. doi: 10.3181/0808-RM-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang YH, Gorvel JP, Chu YT, Wu JJ, Lei HY. Helicobacter pylori impairs murine dendritic cell responses to infection. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10844. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lei HY, Wang YH, Wu JJ. The Autophagic Induction in Helicobacter pylori-Infected Macrophage. Exp Biol Med. 2009;234:171–80. doi: 10.3181/0808-RM-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Faraoni I, Antonetti FR, Cardone J, Bonmassar E. miR-155 gene: a typical multifunctional microRNA. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1792:497–505. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2009.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eisenberg I, Eran A, Nishino I, Moggio M, Lamperti C, Amato AA, et al. Distinctive patterns of microRNA expression in primary muscular disorders. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:17016–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708115104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ikeda S, Kong SW, Lu J, Bisping E, Zhang H, Allen PD, et al. Altered microRNA expression in human heart disease. Physiol Genomics. 2007;31:367–73. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00144.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taganov KD, Boldin MP, Chang KJ, Baltimore D. NF-kappaB-dependent induction of microRNA miR-146, an inhibitor targeted to signaling proteins of innate immune responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:12481–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605298103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tili E, Michaille JJ, Cimino A, Costinean S, Dumitru CD, Adair B, et al. Modulation of miR-155 and miR-125b levels following lipopolysaccharide/TNF-alpha stimulation and their possible roles in regulating the response to endotoxin shock. J Immunol. 2007;179:5082–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.5082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perry MM, Moschos SA, Williams AE, Shepherd NJ, Larner-Svensson HM, Lindsay MA. Rapid changes in microRNA-146a expression negatively regulate the IL-1beta-induced inflammatory response in human lung alveolar epithelial cells. J Immunol. 2008;180:5689–98. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.8.5689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu H, Wu H, Liu X, Li B, Chen Y, Ren X, et al. Regulation of autophagy by a beclin 1-targeted microRNA, miR-30a, in cancer cells. Autophagy. 2009;5:816–23. doi: 10.4161/auto.9064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meenhuis A, van Veelen PA, de Looper H, van Boxtel N, van den Berge IJ, Sun SM, et al. MiR-17/20/93/106 promote hematopoietic cell expansion by targeting sequestosome 1-regulated pathways in mice. Blood. 2011;118:916–25. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-336487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xiao J, Zhu X, He B, Zhang Y, Kang B, Wang Z, et al. MiR-204 regulates cardiomyocyte autophagy induced by ischemia-reperfusion through LC3-II. J Biomed Sci. 2011;18:35. doi: 10.1186/1423-0127-18-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gabriely G, Teplyuk NM, Krichevsky AM. Context effect: microRNA-10b in cancer cell proliferation, spread and death. Autophagy. 2011;7:1384–6. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.11.17371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gabriely G, Teplyuk NM, Krichevsky AM. Context effect: microRNA-10b in cancer cell proliferation, spread and death. Autophagy. 2011;7:1384–6. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.11.17371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xiao B, Liu Z, Li BS, Tang B, Li W, Guo G, et al. Induction of microRNA-155 during Helicobacter pylori infection and its negative regulatory role in the inflammatory response. J Infect Dis. 2009;200:916–25. doi: 10.1086/605443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kihara A, Kabeya Y, Ohsumi Y, Yoshimori T. Beclin-phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase complex functions at the trans-Golgi network. EMBO Rep. 2001;2:330–5. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pattingre S, Tassa A, Qu X, Garuti R, Liang XH, Mizushima N, et al. Bcl-2 antiapoptotic proteins inhibit Beclin 1-dependent autophagy. Cell. 2005;122:927–39. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Geng J, Klionsky DJ. The Atg8 and Atg12 ubiquitin-like conjugation systems in macroautophagy. ‘Protein modifications: beyond the usual suspects’ review series. EMBO Rep. 2008;9:859–64. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klionsky DJ, Cuervo AM, Seglen PO. Methods for monitoring autophagy from yeast to human. Autophagy. 2007;3:181–206. doi: 10.4161/auto.3678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mizushima N. Methods for monitoring autophagy. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:2491–502. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Terebiznik MR, Raju D, Vázquez CL, Torbricki K, Kulkarni R, Blanke SR, et al. Effect of Helicobacter pylori’s vacuolating cytotoxin on the autophagy pathway in gastric epithelial cells. Autophagy. 2009;5:370–9. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.3.7663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gerrits MM, van Vliet AH, Kuipers EJ, Kusters JG. Helicobacter pylori and antimicrobial resistance: molecular mechanisms and clinical implications. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6:699–709. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70627-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Amieva MR, Salama NR, Tompkins LS, Falkow S. Helicobacter pylori enter and survive within multivesicular vacuoles of epithelial cells. Cell Microbiol. 2002;4:677–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2002.00222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Terebiznik MR, Vazquez CL, Torbicki K, Banks D, Wang T, Hong W, et al. Helicobacter pylori VacA toxin promotes bacterial intracellular survival in gastric epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 2006;74:6599–614. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01085-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Necchi V, Candusso ME, Tava F, Luinetti O, Ventura U, Fiocca R, et al. Intracellular, intercellular, and stromal invasion of gastric mucosa, preneoplastic lesions, and cancer by Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1009–23. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chu YT, Wang YH, Wu JJ, Lei HY. Invasion and multiplication of Helicobacter pylori in gastric epithelial cells and implications for antibiotic resistance. Infect Immun. 2010;78:4157–65. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00524-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deretic V, Levine B. Autophagy, immunity, and microbial adaptations. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5:527–49. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li J, Donath S, Li Y, Qin D, Prabhakar BS, Li P. miR-30 regulates mitochondrial fission through targeting p53 and the dynamin-related protein-1 pathway. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000795. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martinez I, Cazalla D, Almstead LL, Steitz JA, DiMaio D. miR-29 and miR-30 regulate B-Myb expression during cellular senescence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:522–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017346108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zaragosi LE, Wdziekonski B, Brigand KL, Villageois P, Mari B, Waldmann R, et al. Small RNA sequencing reveals miR-642a-3p as a novel adipocyte-specific microRNA and miR-30 as a key regulator of human adipogenesis. Genome Biol. 2011;12:R64. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-7-r64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Atanackovic D, Hildebrandt Y, Jadczak A, Cao Y, Luetkens T, Meyer S, et al. Cancer-testis antigens MAGE-C1/CT7 and MAGE-A3 promote the survival of multiple myeloma cells. Haematologica. 2010;95:785–93. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.014464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu F, Deng H, Yao H, Liu Q, Su F, Song E. Mir-30 reduction maintains self-renewal and inhibits apoptosis in breast tumor-initiating cells. Oncogene. 2010;29:4194–204. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Joglekar MV, Patil D, Joglekar VM, Rao GV, Reddy DN, Mitnala S, et al. The miR-30 family microRNAs confer epithelial phenotype to human pancreatic cells. Islets. 2009;1:137–47. doi: 10.4161/isl.1.2.9578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Duisters RF, Tijsen AJ, Schroen B, Leenders JJ, Lentink V, van der Made I, et al. miR-133 and miR-30 regulate connective tissue growth factor: implications for a role of microRNAs in myocardial matrix remodeling. Circ Res. 2009;104:170–8, 6p, 178. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.182535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Song PP, Hu Y, Liu CM, Yan MJ, Song G, Cui Y, et al. Embryonic ectoderm development protein is regulated by microRNAs in human neural tube defects. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204:544–, e9-17. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Agrawal R, Tran U, Wessely O. The miR-30 miRNA family regulates Xenopus pronephros development and targets the transcription factor Xlim1/Lhx1. Development. 2009;136:3927–36. doi: 10.1242/dev.037432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xiao B, Li W, Guo G, Li B, Liu Z, Jia K, et al. Identification of small noncoding RNAs in Helicobacter pylori by a bioinformatics-based approach. Curr Microbiol. 2009;58:258–63. doi: 10.1007/s00284-008-9318-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.