Abstract

Many viruses have evolved elegant strategies to co-opt cellular autophagic responses to facilitate viral propagation and evasion of immune surveillance. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) establishes a life-long persistent infection in its human host, and is etiologically linked to several cancers. KSHV gene products have been shown to modulate autophagy but their contribution to pathogenesis remains unclear. Our recent study demonstrated that KSHV subversion of autophagy promotes bypass of oncogene-induced senescence (OIS), an important host barrier to tumor initiation. These findings suggest that KSHV has evolved to subvert autophagy, at least in part, to establish an optimal niche for infection, concurrently dampening host antiviral defenses and allowing the ongoing proliferation of infected cells.

Keywords: KSHV, oncogene, DNA damage, autophagy, oncogene-induced senescence

Oncogene-induced senescence (OIS) represents an important barrier to tumor initiation, sensing oncogenic stress and enforcing permanent cell cycle arrest. The OIS program is rapid and dynamic. Oncogene activation causes transient hyper-proliferation that results in genotoxic stress and activation of DNA damage responses (DDRs) that initiate cell cycle exit. Autophagy is an important effector mechanism of OIS; during the transition to the senescent phenotype, increases in autophagic flux coincide with active translation, causing dramatic increases in cell size and production of secretory proteins that reinforce senescence (known as the senescence-associated secretory phenotype—SASP). Several autophagy genes have been assigned roles as tumor suppressors, and experimental disruption of autophagy promotes senescence bypass. The accumulating evidence suggests that autophagy can contribute to tumor suppression by enforcing OIS.

Approximately 15% of all human cancers share an underlying infectious etiology. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV, a.k.a. human herpesvirus-8) is the infectious cause of a dermal tumor known as Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS). Like all herpesviruses, KSHV can establish a reversible form of quiescent infection known as latency. During latency, the KSHV genome is physically tethered to host chromatin and viral gene expression is limited to a subset of gene products that perform important housekeeping functions. KS tumors are replete with latently infected endothelial cells (ECs) that proliferate abnormally, so KSHV latent gene products are also presumed to play important roles in disabling host antiproliferative defenses.

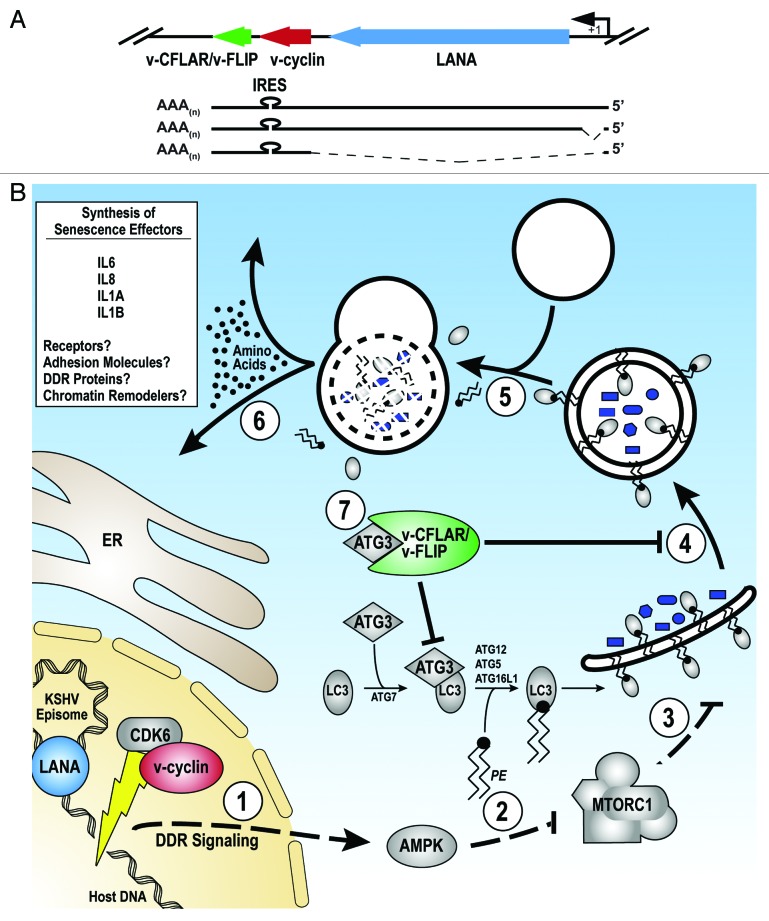

Our recent study revealed that cells latently infected with KSHV display clear indications of oncogenic stress and activated DDRs, but are refractory to senescence, suggesting active viral evasion of the OIS program. Therefore, we hypothesized that latent gene products undermine OIS and allow the ongoing proliferation of KSHV-infected cells despite the accrual of DNA damage. We identified two such gene products, viral-cyclin (v-cyclin) and viral-FLICE-inhibitory protein (v-CFLAR/v-FLIP), that coordinate an attack on host cell antiproliferative defenses. A striking feature of the KSHV genome is the presence of more than a dozen pirated human genes, the legacy of millennia of co-evolution between this lineage of viruses and our primate ancestors. Even more fascinating is the fact that two of these pirated genes, v-cyclin and v-CFLAR/v-FLIP, are co-expressed from the same spliced latent transcript, an arrangement that suggests functional interdependence (Fig. 1A). The complementary roles that v-cyclin and v-CFLAR/v-FLIP play in controlling OIS provides a solid rationale for their genetic linkage.

Figure 1. v-CFLAR/v-FLIP subversion of autophagy impairs v-Cyclin OIS. (A) Schematic of the KSHV latent transcription unit encoding LANA, v-cyclin and v-CFLAR/v-FLIP. v-CFLAR/v-FLIP translation initiates from an internal ribosomal entry site (IRES). (B) A model for the functions of KSHV proteins in the regulation of autophagy and OIS during latency. (Steps 1 and 2) LANA tethers the KSHV episome to host chromatin. v-Cyclin triggers oncogenic stress and DDRs, which activate AMPK and repress MTORC1. (Steps 3–5) The AMPK-MTOR signaling axis promotes phagophore nucleation and engulfment of cytoplasmic material within autophagosomes for autolysosomal degradation. (Step 6) Amino acids and other molecules liberated by autophagy facilitate bulk synthesis of pro-senescence factors through coupling of cellular catabolic and biosynthetic pathways. (Step 7) v-CFLAR/v-FLIP antagonizes host OIS signaling by inhibiting autophagy (via ATG3) and limiting synthesis of factors that contribute to senescent cell remodeling.

v-Cyclin: A Viral Oncogene that Triggers OIS

v-Cyclin, like the related cellular D-type cyclins, forms an active holoenzyme with cyclin-dependent kinase 6 (CDK6). However, v-cyclin-CDK6 heterodimers differ from their host counterparts in that they have a broader substrate range, phosphorylating proteins that regulate all phases of the cell cycle. Furthermore, v-cyclin-CDK6 complexes are refractory to the action of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors (CKIs). These adaptations allow v-cyclin to constitutively dysregulate the cell cycle. It therefore comes as little surprise that v-cyclin, like the product of the canonical senescence-inducing oncogene RAS, triggers OIS (Fig. 1B). Indeed, v-cyclin expression in primary cells induces profound DDRs, causing TP53 activation, rapid cell cycle exit and formation of discrete heterochromatin domains, termed senescence-associated heterochromatic foci (SAHF), that silence gene expression. Our study demonstrated that, similar to cells expressing oncogenic RAS, v-cyclin-expressing cells display a striking upregulation of autophagy that correlates with adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) activation and repression of mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (MTORC1) signaling. Importantly, when we co-expressed short-hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) that ablate the essential autophagy regulators ATG5 or ATG7, we found v-cyclin OIS and its associated secretory phenotype to be appreciably compromised. Together, these observations demonstrate that autophagy is required for v-cyclin OIS.

v-CFLAR/v-FLIP Prevents v-Cyclin-Induced Senescence by Subverting Autophagy

Our study showed that latently infected primary cells display the hallmarks of v-cyclin-induced oncogenic stress and DDR checkpoint activation, but fail to senesce. To identify KSHV latency genes capable of OIS bypass, we performed an ectopic expression screen. Co-expression of v-FLIP with v-cyclin potently suppresses OIS and increased proliferation through a mechanism downstream of v-cyclin-induced DNA damage. Importantly, v-CFLAR/v-FLIP was recently shown to potently inhibit autophagy by binding and inhibiting ATG3, thereby preventing LC3 targeting to phagophores (Fig. 1B). Therefore, we hypothesized that v-CFLAR/v-FLIP facilitates OIS bypass during latent KSHV infection by suppressing autophagy.

To test this hypothesis, we adapted a dominant negative inhibition strategy to block v-CFLAR/v-FLIP function in latently infected cells. We employed fragments of v-CFLAR/v-FLIP comprising the ATG3-binding domains, which selectively inhibit v-CFLAR/v-FLIP anti-autophagy function. Importantly, these v-CFLAR/v-FLIP dominant negative constructs fail to interact with cellular CFLAR/FLIP and are insufficient to activate autophagy on their own. Remarkably, when we expressed these v-CFLAR/v-FLIP dominant negative constructs in cells latently infected with KSHV, not only was autophagy rescued, but the infected cells rapidly senesced. Similarly, treatment of latently infected cells with the MTORC1 inhibitor rapamycin effectively overwhelms the anti-autophagy functions of v-CFLAR/v-FLIP and induces senescence. Together, these data demonstrate that v-CFLAR/v-FLIP subversion of autophagy is necessary to prevent senescence during latent KSHV infection.

Conclusion

It has become increasingly apparent that many viruses have evolved mechanisms to co-opt autophagy. Our work describes an auxiliary function for viral autophagy suppression in disrupting host antiproliferative defenses. We speculate that OIS represents a barrier that all tumor viruses need to overcome. Viruses are excellent teachers, and study of KSHV is likely to provide novel insights into the mechanisms of autophagy and effects on viral replication and pathogenesis.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/autophagy/article/20340