Abstract

We use a recently developed mathematical model that integrates a reduced representation of the brainstem respiratory neural controller together with peripheral gas exchange and transport to study numerically the dynamic response of the respiratory system to several physiological stimuli. We compare between the system responses with two major sources of delay: circulatory transport vs. neural feedback dynamics, and we show that the dynamics of the neural feedback processes dictates the dynamic response to hypoxia and hypercapnia. The source of the circulatory delay (blood velocity vs. distance from the lungs to chemoreceptors) was found to be important. Our model predicts that periodic breathing is associated with the ventilatory “afterdischarge” (slow recovery of ventilation) after a brief perturbation of CO2. We also predict that there could be two possible mechanisms for the appearance of periodic breathing and that circulatory delay is not a necessary condition for this to occur in certain cases.

Keywords: Brainstem, respiration, apnea, hypercapnia, hypoxia, feedback regulation

1 Introduction

Breathing in mammals involves many interacting dynamical processes including the generation and transmission of neural activity in the brain, contraction of the respiratory muscles, air flow in the lungs, gas diffusion and transport in the blood, and feedback control mechanisms for homeostatic regulation of blood gas content. These processes are associated with temporal delays of different nature that can affect the dynamic regulatory responses of the system to perturbations of lung and blood gas compositions. Defining functional consequences of these different sources of delays is fundamental for understanding homeostatic regulation of breathing.

One of these delays, which represents a major structural feature in the system, is considered to be particularly important— time delay associated with gas transport between the lungs and the chemosensors outside and within the central nervous system (also called transport delay). Many investigators (see for example Batzel et al., 2006; Eldridge, 1996; Fowler and Kalamangalam, 2002; Grodins et al., 1967; Khoo et al., 1982; Khoo and Yamashiro, 1989; Lu et al., 2002; Mackey and Glass, 1977; Milhorn and Guyton, 1965) consider transport delay to be crucial for the appearance of complex dynamical behaviour in the system’s response to perturbations including the appearance of periodic breathing such as Cheyne-Stokes Respiration (CSR) and other clustered breathing patterns. Less studied is delay in the system response to perturbations of blood gas compositions, most apparent in the transient response (how the system approaches steady-state) that results from the dynamic process itself of neural feedback mechanisms. These dynamics may also contribute to apneas as elaborated in our previous work (Ben-Tal and Smith, 2008) and to the appearance of clustered breathing patterns as we show in this paper. The lack of studies of the transient behaviour of the system to perturbations of blood gas compositions is due to lack of recent experiments (which routinely only look at the steady-state behaviour) and the lack of mathematical models that can simulate such transients. Indeed, most published mathematical models for the control of breathing use an empirical relationship between minute ventilation and blood gas concentrations, based on the steady-state experiments, as an input to the model (see for example Batzel et al., 2006; Batzel and Tran, 2000; Fowler and Kalamangalam, 2002; Grodins et al., 1967; Khoo et al., 1982; Milhorn and Guyton, 1965). Here for the first time, we compare between system responses with the two major sources of delay: circulatory transport vs. neural feedback dynamics, and we study numerically, using a recently developed respiratory system model (Ben-Tal and Smith, 2008), how these different sources of delay affect the responses of the mammalian respiratory system to several physiological stimuli.

Our recently developed mathematical model couples a reduced representation of the brainstem respiratory neural controller with peripheral gas exchange and transport mechanisms. The model regulates both frequency and amplitude of breathing in response to partial pressures of oxygen and carbon dioxide in the blood using as the feedback mechanisms either proportional (P) and/or proportional plus integral (PI) controllers (both standard controllers in control theory). In Ben-Tal and Smith (2008) we simulated both the dynamic and the steady-state responses of the system to increased levels of inhaled CO2 (hypercapnia) and decreased levels of inhaled O2 (hypoxia), and found in general that an I component in the feedback mechanism is crucial for mimicking a number of experimental observations of the system response dynamics such as the slow increase in tidal volume in response to hypercapnia and the slow decline in ventilation once the inhaled CO2 was returned to normal. These and other results elaborated in Ben-Tal and Smith (2008), pointed to an important role of delay associated with neural feedback dynamics as represented by the PI controller, which we hypothesize and further examine here, plays a more significant role in regulating system dynamical responses than previously appreciated. However, time delays in the circulatory system were not incorporated in the previous model, and it is therefore important to compare the system’s response to disturbances with and without transport delay. Our modeling approach enabled us to study for the first time the effect of each of the delay sources separately as well as when coupled together and hence to explain important features of the system responses not captured by controller dynamics alone or by transport delay alone.

In the present study we therefore extended the analysis in Ben-Tal and Smith (2008), by incorporating transport delays with two different types of controllers (P and PI) for comparison. While some of our results are similar to analytical results based on linear control theory in much simpler dynamical systems, the nonlinearity and complexity of our computational model means that we cannot apply known control theorems directly to our model and need to rely on numerical simulation studies. We found that a PI controller with or without circulatory transport delay qualitatively fits all the experimental observations better than a P-controller with delay. We show that transport delay does not contribute to many important features in the system’s response to hypoxia and hypercapnia. Increased time delay however resulted in the appearance of periodic breathing patterns in our model, but we also show that this is not a necessary structural feature to explain the phenomenon. These results generally support our hypothesis that the dynamics of the neural feedback mechanism(s) dictate system dynamical responses in many physiological conditions.

2 Methods

2.1 Numerical methods and model

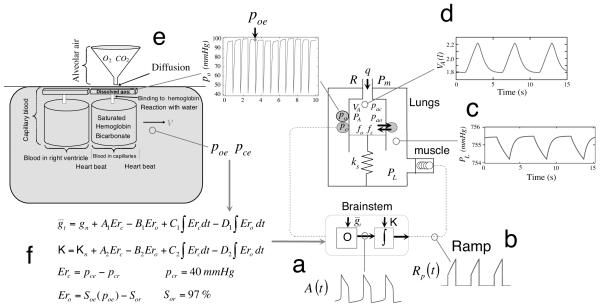

We used a mathematical model we have developed in Ben-Tal (2006) and in Ben-Tal and Smith (2008). All model equations as described in detail there were used here without modification except for the addition of delays as specified below. The key mathematical equations are summarized in the Appendix. All model simulations were run using the subroutine Radau5 (this is an implicit Runge-Kutta method of order 5, available online, http://www.unige.ch/~hairer/software.html). A schematic description of the model with sample model outputs is shown in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Schematic description of the model with sample model outputs. See text for full description of components labelled by a - f.

The brainstem part consists of two interacting components: an oscillator responsible for rhythm generation (the output of which is shown in Fig. 1a) and an inspiratory pattern generator that is driven by the oscillator and transforms the drive signal into a ramp pattern (the output of which is shown in Fig. 1b). The rhythm generation oscillator represents a known biophysical mechanism that incorporates intrinsic dynamics of the pre-Bötzinger complex (pre-BötC), which generates rhythmic excitatory drive in the respiratory neural network during inspiration (Feldman and Del Negro, 2006; Smith et al., 1991, 2000). This mechanism allows for frequency control by input drives ( in our model) over a wide dynamic range, as well as multi-state behaviour (no activity, oscillations, and tonic activity). The oscillator model we currently use does not take into account synaptic interactions (e.g. phasic inhibitory inputs from other medullary circuits and their control by circuits in the pons; see Smith et al., 2007) that occur in the intact system at the level of the pre-BötC, but the model’s response to excitatory input drive in terms of frequency control at the level of the pre-BötC is similar to more complex activity models that incorporate such interactions (Rubin et al., 2009).

The transformation of the drive from the pre-BötC oscillator into a ramping neural signal is represented by a leaky integration process. This ramping waveform is characteristic of the neural elements in the ventral respiratory group (VRG) of the medulla that drive the motoneurons innervating the diaphragm and cause lung ventilation. A crucial factor for maintaining the ramp evolution in the neural system is a steady external excitatory drive to the ramp generator (Rubin et al., 2009; Smith et al., 2007). This continuous baseline excitation is represented in our model by the parameter K which is added to the integrated signal and therefore influences the amplitude of the ramp signal (and hence the amplitude of inspiration).

We assume that the force generator at the level of respiratory muscles (diaphragm) is following the waveform of phrenic nerve activity (the ramp signal in our model) and that this is the essential representation for muscle force production and pleural pressure waveform generation. We model the muscle as a spring, excited by an external force (which is proportional to the ramp signal). The pleural pressure waveform is seen in Fig. 1c.

The lung is modeled by a single container which has a moving plate attached to a spring (note that spring compression represents lung expansion). Changes in the pleural pressure cause the alveolar pressure to change resulting in air flow in and out of the lung (the lung volume as a function of time is shown in Fig. 1d). Gas exchange and gas transport are modeled by a “conveyor” model, shown in Fig. 1e. It is assumed that the volume of the capillaries is the same as the heart stroke volume and that the transit time of blood through the lung is the same as the time interval between heart beats. The moving “conveyor” is simulated by re-initializing the values of pc , the blood partial pressures of carbon dioxide, po , the blood partial pressures of oxygen and z , the concentration of bicarbonate in the blood, every heart beat (see Ben-Tal, 2006 for more details). The values of pc and po at the end of each inter-beat interval (i.e. just before they are re-initialized) represent the blood partial pressures at the end of the capillaries and are denoted by pce and poe , respectively. These values are updated every heart beat and are used to calculate the input drives ( and K) in the control model (see Fig. 1f, and Appendix). If the circulatory delay is not taken into account then pce and poe are taken at the current time t . If the circulatory delay is taken into account then pce and poe are taken at the previous time t − τ . The time delay, τ , is a factor of the distance of the chemoreceptors from the lungs and the velocity of blood in the circulatory system. In our model τ = n*TL , where n is the number of heart beats between the end of the capillary and the chemoreceptors ( n could be a fraction) and TL is the time between two heart beats. n can be thought of as the distance and TL can be thought of as 1/blood velocity.

We have studied the dynamic response for a range of delay values up to 32 s (which could represent an extreme physiological condition such as congestive heart failure) and show for most cases the dynamic response for two delay values (8.333 s and 16.666 s ) that represent the trend seen when the time delay is increased. The delay values we chose to show are also in line with other studies where the delay values range between 5 s and 15 s (Batzel et al., 2006; Fowler and Kalamangalam, 2002; Khoo et al., 1982; Lange et al., 1966; Milhorn and Guyton, 1965; Topor et al., 2007).

3 Results

3.1 Dynamic responses to hypercapnia

We studied the dynamic response to hypercapnia by mimicking an experiment described in Fig. 5-1 of Comroe (1974) where normal concentration of gas (0% CO2 , 21% O2) is inhaled by a lightly anesthetized dog for t < 120 s , 7.5% CO2 is inhaled for 120 ≤ t < 240 s , and 0% CO2 is inhaled again for t ≥ 240 s . One feature of the dynamic response seen experimentally is a slow increase in amplitude once 7.5% CO2 is administrated (Comroe, 1974, second graph in Fig. 5-1) and then a slow decrease in amplitude once normal air is inhaled again. The experiment shown in Fig. 5-1 of Comroe (1974) also reveals that over a period of about 2.5 min the ventilation does not reach steady-state. In Ben-Tal and Smith (2008) we studied the dynamic response when there was no circulatory delay (i.e. pce and poe were taken at the current time t ). Here we repeat the simulations when delay has been included in the model. Our aim was to test numerically which of the two configurations can capture the experimental features described above. The special cases of the feedback functions used in the simulations are given in Table 3.

Fig. 5.

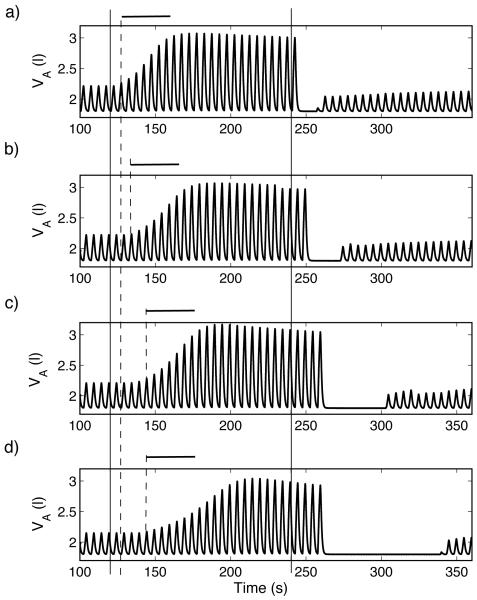

Dynamic response to hypoxia of a P-controller (case 2, Table 3). For t < 120 s , fom = 21% , for 120 ≤ t < 240 s , fom = 5% , and for t ≥ 240 s , fom = 100% . The inclusion of delay increases the apnea length and results in increased transient oscillations that are more persistent in d) when the delay is mainly due to reduced heart beats (increased TL) and resemble CSR. Increased delay increases the time between the onset of the stimulus (solid, vertical lines, marked at t = 120 s and t = 240 s) and the onset of the response (dashed, vertical line). The only significant change to the time it takes the system to reach steady-state (marked with bold horizontal lines) is in d). a)TL = 0.8333 s , n = 0, τ = 0 s . b)TL = 0.8333 s , n = 10, τ = 8.333 s . c) TL = 0.8333 s , n = 20, τ = 16.666 s . d)TL = 1.6666 s , n = 10, τ = 16.666 s .

Table 3. Special cases of the feedback functions.

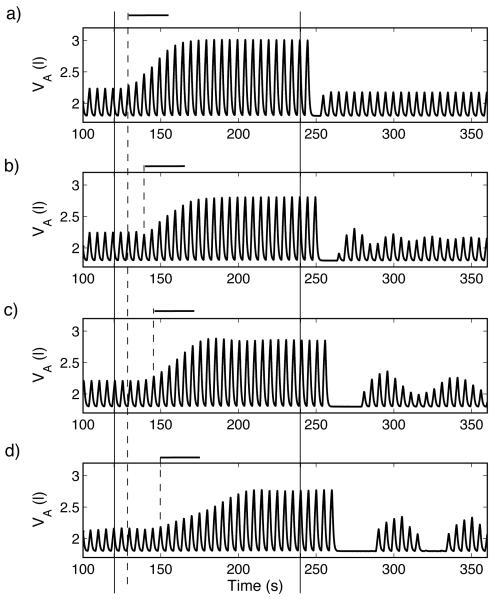

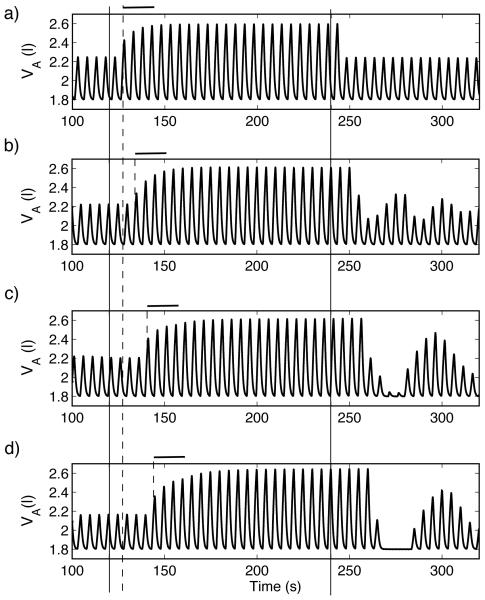

Figure 2 shows the response of a P-controller while Figure 3 shows the response of a PI-controller, both with amplitude and CO2 control only. In both figures part a) shows the response when there is no delay in the system (TL = 0.8333 s , n = 0 , τ = 0 s ), b) and c) show the response for two delay values (τ = 8.333 s and τ = 16.666 s , respectively) when n , the number of heart beats between the end of the capillary and the chemoreceptors, is increased (n = 10 and n = 20 respectively), while d) shows the dynamic response when TL , the transient time in the lungs, is increased ( TL = 1.6666 s , n = 10 , τ = 16.666 s ). In both figures solid lines mark the times t = 120 s and t = 240 s and dashed lines mark the estimated time the system starts to respond. Bold horizontal lines in Fig. 2 mark the approximate transient time in the dynamic response of the system with no delay. As can be seen, the slow increase followed by a slow decrease in ventilation and the fact that over the observed period of time the system does not reach steady-state, are all captured in Fig. 3 by the PI-controller, which represents the intrinsic dynamics of the feedback mechanism. Also note that the response seen in Fig. 2, which represents a mechanism with only transport delay, differs from that seen in Fig.3 qualitatively.

Fig. 2.

Effect of increased delay on the dynamic response of a P-controller (case 1, Table 3) to hypercapnia. For t < 120 s , fcm = 0% , for 120 ≤ t < 240 s , fcm = 7.5% , and for t ≥ 240 s , fcm = 0% . Increased delay increases the time between the onset of the stimulus (solid, vertical lines, marked at t = 120 s and t = 240 s) and the onset of the response (dashed, vertical line) but did not change significantly the time it takes the system to reach steady-state (marked with bold horizontal lines). Increased delay leads to transient periodic breathing that are more apparent when the delay is mainly due to reduced heart beats (increased TL). a) No delay (TL = 0.8333 s , n = 0). b) Delay of 8.333 s (TL = 0.8333 s , n = 10). c) Delay of 16.666 s (TL = 0.8333 s , n = 20). d) Delay of 16.666 s (TL = 1.6666 s , n = 10).

Fig. 3.

Dynamic response of a PI-controller (case 3, Table 3) to hypercapnia. For t < 120 s , fcm = 0% , for 120 ≤ t < 240 s , fcm = 7.5% , and for t ≥ 240 s , fcm = 0% . Increased delay increases the time between the onset of the stimulus (solid, vertical lines, marked at t = 120 s and t = 240 s) and the onset of the response (dashed, vertical line) but did not change significantly the rise time. Note that the system does not reach steady-state and that increased delay did not lead to transient periodic breathing. a) TL = 0.8333 s , n = 0 , τ = 0 s . b)TL = 0.8333 s , n = 10 , τ = 8.333 s . c) TL = 0.8333 s , n = 20, τ = 16.666 s . d)TL = 1.6666 s , n = 10, τ = 16.666 s .

Fig. 2 and 3 also show that the delay affects the time it takes the system to respond (i.e. there is a delay between the time 7.5% CO2 is administrated and the time the amplitude starts to increase). This delayed response is seen experimentally and in our model for both the P- and the PI-controllers. An additional delay does add some transient periodic oscillations to the model in Fig. 2. Increased delays result in increased transient oscillations that resemble waxing and waning breathing patterns characteristic of Cheyne Stokes Respiration (CSR) in Fig. 2 c) and d) at t > 240 s with the return to normal inspired CO2 levels. Note that such oscillations do not occur under these conditions with the PI-controller. Figures 2 c) and d) also illustrate that the source of the delay is important. When the delay is due to a reduced blood velocity (increased TL), apnea appears in the system (Fig. 2d) even though the overall delay is the same as in Fig. 2c. We have studied longer delays (up to 32 s ) and the same trend continues.

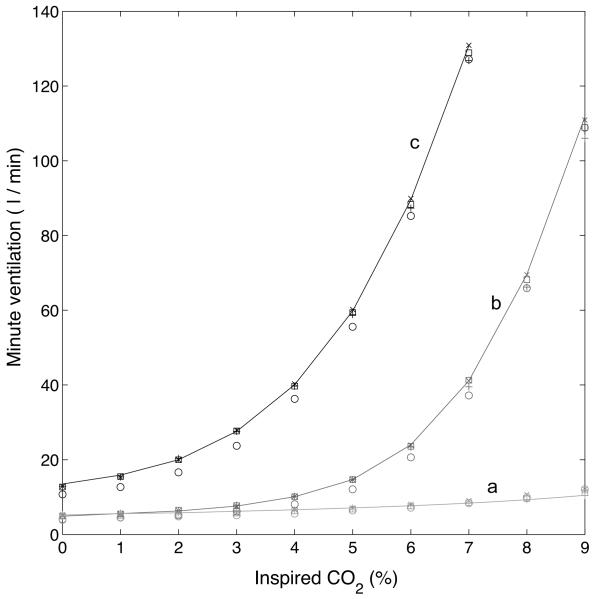

Figure 4 shows the steady-state minute ventilation as a function of inspired CO2 , calculated at the end of 200 s . a (red color) represents a P-controller where the inspired O2 is 21% , b (blue color) represents a PI-controller where the inspired O2 is 21% and c (black color) represents a PI-controller where the inspired O2 is 5% . The solid line shows the response without delay, the symbol x shows the response with τ = 8.333 s , the square symbol shows the response with τ = 16.666 s when n = 20 and TL = 0.8333 s , the circle symbol shows the response with τ = 16.666 s when n = 10 and TL = 1.6666 s , and the symbol + shows the response with τ = 32.5 s when n = 39 for a PI-controller (graphs b and c) and τ = 25 s with n = 30 for a P-controller (graph a, periodic breathing appears in the P-controller for n > 30 ). As can be seen, the additional delay did not change the response qualitatively. The steep rise in the minute ventilation once the inspired CO2 is larger than some threshold has been seen experimentally as well as the shift to the left when the inspired O2 is reduced (see for example Comroe, 1974 and Kellogg, 1964). This behaviour is captured by the PI-controller and has been explained in Ben-Tal and Smith (2008) by the fact that the system cannot reach steady-state over the time interval examined for larger values of CO2.

Fig. 4.

Steady-state minute ventilation as a function of inspired CO2 , calculated at the end of 200 s . a (Red) - P controller (case 2, Table 3), inspired O2 is 21%. b (Blue) - PI controller (case 4), inspired O2 is 21%. c (Black) - PI-controller (case 4), inspired O2 is 5% . Solid line - the response without delay. x - the response with τ = 8.333 s . Square - the response with τ = 16.666 s when n = 20 and TL = 0.8333 s . Circle - the response with τ = 16.666 when n = 10 and TL = 1.6666 s , + - the response with τ = 32 s when n = 39 for a PI controller and τ = 25 s with n = 30 for a P-controller. The additional delay did not change the response qualitatively. The steep rise in the minute ventilation once the inspired CO2 is larger than some threshold as well as the shift to the left when the inspired O2 is reduced is captured by the PI-controller.

3.2 Dynamic responses to hypoxia

We studied the dynamic response to hypoxia by mimicking an experiment described by Fig. 4-10 in Comroe (1974) where normal concentration of gas ( 0% CO2 , 21% O2) is inhaled for t < 120 s by an anesthetized dog, 5% O2 is inhaled for 120 ≤ t < 240 s , and 100% O2 is inhaled for t ≥ 240 s . A typical response seen in these experiments is an increase in amplitude once 5% O2 is inhaled followed by apnea once 100% O2 is administrated. This response has been seen in the models when there was no delay (Ben-Tal and Smith, 2008), but the apnea was significantly shorter in a P-controller. Here we repeat the simulations when delay is included in the feedback function. We examined amplitude control and use the same delay for both CO2 and O2 . Figure 5 shows the response to hypoxia of a P-controller while Figure 6 shows the response of a PI-controller. In both figures part a) shows the response when there is no delay in the system (TL = 0.8333 s , n = 0 , τ = 0 s ), b) and c) show the response for two delay values (τ = 8.333 s and τ = 16.666 s , respectively) when the distance of the chemoreceptors is increased ( n = 10 and n = 20, respectively), and d) shows the dynamic response when the delay results from a decrease in blood velocity ( TL = 1.6666 s , n = 10 , τ = 16.666 s ). In both figures solid lines mark the times t = 120 s and t = 240 s and dashed lines mark the estimated time the system starts to respond. Bold horizontal lines mark the approximate transient time in the dynamic response of the system with no delay.

Fig. 6.

Dynamic response to hypoxia of a PI-controller (case 4, Table 3). For t < 120 s , fom = 21% , for 120 ≤ t < 240 s , fom = 5% and for t ≥ 240 s , fom = 100% . Solid lines mark the times t = 120 s and t = 240 s and dashed lines mark the estimated time the system starts to respond. Bold horizontal lines mark the approximate transient time in the dynamic response of the system with no delay. Compared with Figure 5, the periods of apnea that follow the ventilation when inspired O2 is 100% are longer but transient periodic solutions do not appear. a) TL = 0.8333 s , n = 0, τ = 0 s . b) TL = 0.8333 s , n = 10, τ = 8.333 s . c) TL = 0.8333 s , n = 20, τ = 16.666 s . d)TL = 1.6666 s , n = 10, τ = 16.666 s .

As can be seen in Figs. 5 and 6, the inclusion of delay increases the length of apnea in all the controllers at t > 240 s. As with the dynamic response to hypercapnia, increased delays result in increased transient oscillations that resemble CSR in the model with a P-controller (Fig. 5) but not with the PI-controller. Fig. 5 d) illustrates once again that the source of the delay is important. The transient response once 5% O2 is inhaled is longer compared to Fig. 5c (which has the same delay but from a different source), the apnea is longer and CSR is sustained for a considerable length of time (CSR lasted for at least 600 s in our simulations but not shown in Fig. 5).

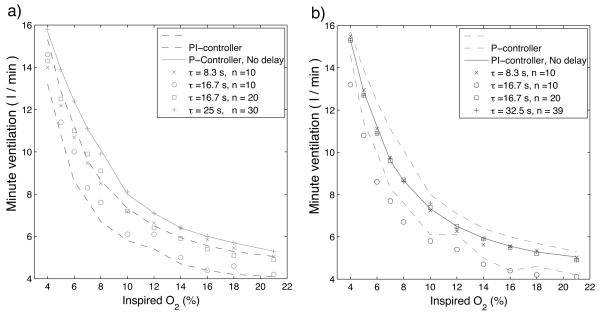

Fig. 7 shows the minute ventilation response to O2 , calculated at the end of 500 s (the choice of 500 s is arbitrary and designed to guarantee steady-state) for a P-controller (Fig. 7a) and a PI-controller (Fig. 7b). Solid lines show the responses with no delay and isolated marks show responses with the delays specified in the legends. For comparison the envelope of responses for the other controller is indicated by the dashed lines in each panel. In both cases, amplitude in response to changes of CO2 and O2 is being controlled. As seen in Fig. 7 the additional delay does not change the response qualitatively. There is a larger increase in minute ventilation for low concentrations of O2 for both the P-controller and the PI-controller but quantitatively not as much as seen experimentally (see for example, Comroe, 1974).

Fig. 7.

Steady-state minute ventilation as a function of inspired O2, calculated at the end of 500 s . Solid lines show the responses with no delay and isolated marks show responses with the delays specified in the legends. a) - P controller (case 2, Table 3). b) - PI controller (case 4). For comparison the envelope of responses for the other controller is indicated by the dashed lines in each panel. There is a larger increase in minute ventilation for low concentrations of O2 for both the P-controller and the PI-controller but not as much as seen experimentally. The additional delay does not change the response qualitatively.

3.3 Appearance of periodic breathing

Figures 2 and 5 above illustrated that CSR, characterized by waxing and waning clusters of breaths separated by apneas, can appear in our model with a P-controller when the time delays are large enough. This result is similar to results that have been found in other published mathematical models that included time delays (see for example, Batzel et al., 2006; Eldridge, 1996; Fowler and Kalamangalam, 2002; Khoo et al., 1982; Khoo and Yamashiro, 1989; Mackey and Glass, 1977; Milhorn and Guyton, 1965). In this section we consider additional insights about the possible origins of CSR or similar periodic breathing patterns that have been gained by analysis of the dynamics of our model.

3.3.1 Two possible mechanisms for the appearance of periodic breathing

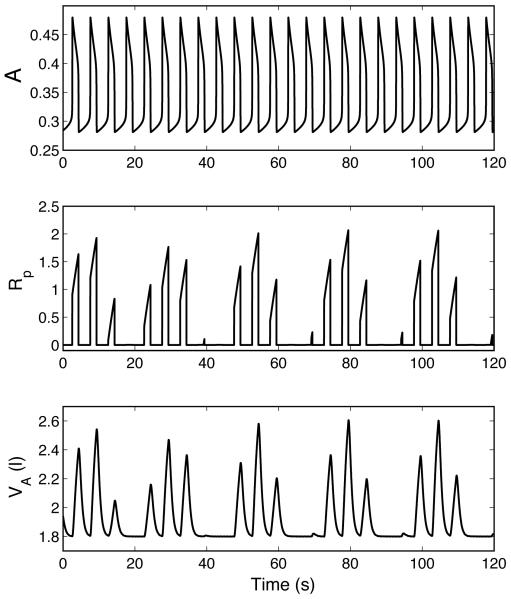

Figures 8 and 9 show periodic breathing that results from two different mechanisms. In Fig. 8 the inspiratory oscillator continues to oscillate normally while a periodic pattern of inspiratory activity appears at the level of the VRG, resulting in a periodic ventilatory pattern. This results from the periodic fluctuations in K, the feedback drive to the VRG ramp generator controlling amplitude of inspiratory activity. In Fig. 9 periodic breathing also appears at the level of the pre-BötC. We found that numerically it was much easier to obtain Fig. 8 than Fig. 9. In Fig. 8 spontaneous periodic breathing appears with the P-controller once the coefficient A2 (in the feedback function for K) is increased from 0.1 to 0.2 and a relatively small delay (τ = 8.333 s ) is introduced. For periodic breathing to appear in Fig. 9 we had to control the frequency using an I-controller with a longer delay (τ =12.5 s ) and force the system into hyperventilation by making the mouth pressure Pm proportional to the ramp signal Rp .

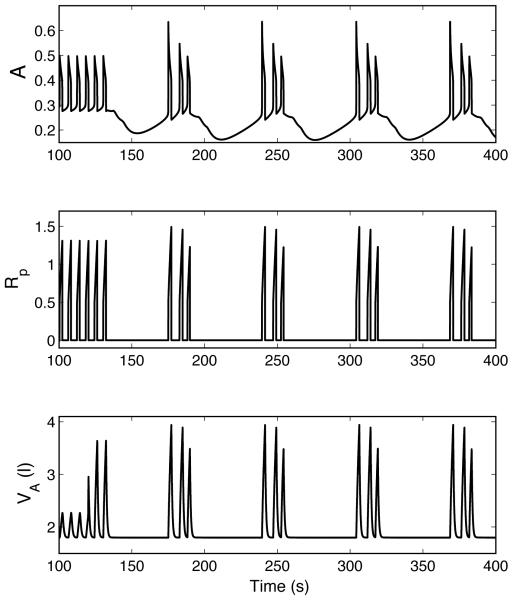

Fig. 8.

Periodic breathing in a P-controller (case 5, Table 3). A is activity of the pre-BötC oscillator and Rp is ramping signal generated by the VRG inspiratory integrator. The inspiratory oscillator continues to oscillate normally while a periodic pattern of inspiratory activity appears at the level of the VRG. TL = 0.8333 s , n = 10, τ = 8.333 s .

Fig. 9.

Periodic breathing in an I-controller (case 6, Table 3). Axis labels are the same as in Fig. 8. Periodic breathing also appears at the level of the pre-BötC. For t < 120 s , Pm = 760 mmHg , for t ≥ 120 s , Pm = 760 + 3Rp(t) mmHg . TL = 0.8333 s , n = 15 , τ = 12.5 s .

3.3.2 Time delay is not a necessary condition for the appearance of periodic breathing

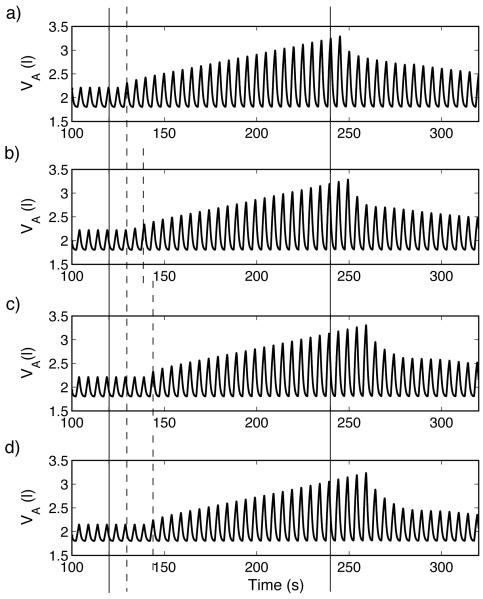

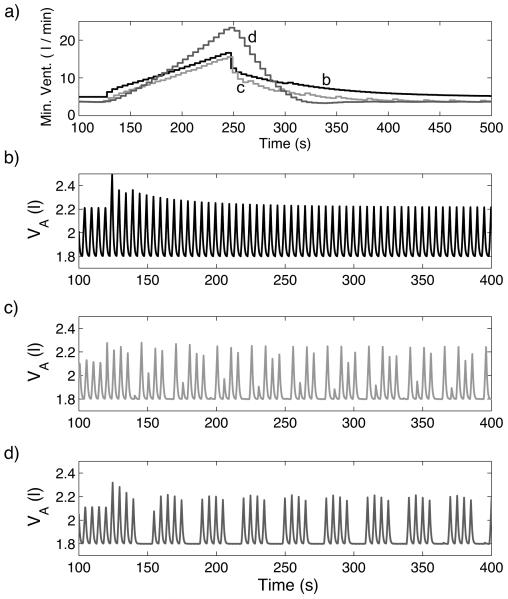

Figure 10 illustrates that periodic breathing can appear in our model under certain conditions when there is no time delay. Figures 10 b) c) and d) show the dynamic response of different controllers when the system is forced into hyperventilation (by making the mouth pressure Pm proportional to the ramp signal Rp) for t > 120 s . All the controllers used in Fig. 10 regulate amplitude, have PI components and respond to changes in both CO2 and O2 . The controllers differ in some parameter values which affect their responses to hypercapnia as illustrated in Fig. 10a. Graph b (black line) in Fig. 10a corresponds to Fig. 10b, graph c (red line) corresponds to Fig. 10c, and graph d (blue line) corresponds to Fig. 10d. The controller whose response is described by graph d (blue line) has increased coefficients of the I component and an increased TL (time between heart beats). Figure 10 shows that there is a correlation between periodic breathing and a faster decline in minute ventilation once the inspired concentration of CO2 is restored to normal following a period of 7.5% inspired CO2 . The slow decline in ventilation after a brief stimulus (also called “ventilatory afterdischarge”) has been the subject of several studies and it has been suggested that a shortening of the length of the ventilatory afterdischarge is linked to disorders of breathing in sleep such as obstructive sleep apnea (see Jordan et al., 2000 for an overview) but, to our knowledge, has not been shown to be linked to periodic breathing in a mathematical model before.

Fig. 10.

Response to hypercapnia (graph a) and to hyperventilation (graphs b-d) in three configurations when there is no circulatory delay. a) For t < 120 s , fcm = 0% , for 120 ≤ t < 240 s , fcm = 7.5% and for t ≥ 240 s , fcm = 0% . b (Black line) – Case 4, Table 3, TL = 0.8333 s , n = 0, τ = 0 s . c (Red line) - same as Black line with TL = 2.3 s. d (Blue line) – Case 7, TL = 2.3 s , n = 0, τ = 0 s . b) - d) For t < 120 s , Pm = 760 mmHg , for t ≥ 120 s , Pm = 760+ 0.7Rp(t) mmHg .

4 Discussion

In this paper we analyzed and compared dynamical responses of a model respiratory system with two separate types of delays: time delays associated with gas transport in the circulatory system and delays due to the dynamic process of the feedback mechanism (modelled implicitly by a PI-controller). By comparing between a P-controller and a PI-controller with or without delay we could study for the first time the effect of each of the delay sources separately as well as when coupled together. Both types of delays affected the system dynamic response to perturbations in blood gas compositions but, as our results show, affect dynamical behavior in different ways. Our numerical studies conducted on a recently developed computational model that integrates a reduced representation of the brainstem respiratory controller with peripheral gas exchange and transport, support our hypothesis that the dynamics of the neural feedback mechanism(s) can dictate system dynamical responses in many physiological conditions.

4.1 Model system responses to hypercapnia and hypoxia

We compared the dynamic and steady-state responses to hypercapnia and hypoxia of P- and PI-controllers with and without time delays and showed that a PI-controller was more consistent with experimental results than a P-controller. The transient times in response to changes of inspired CO2 were slower in the PI-controller than in the P-controller and longer apneas appeared in the PI-controller when 100% O2 was inhaled following 5% O2 . We chose to compare our modeling results with this experimental paradigm because it represents a complex dynamical sequence with well-described features that could serve as a metric for data-model comparisons. Considering the system CO2 response curves, the sharp increase in minute ventilation when inspired CO2 was greater than 5% occurred with the PI-controller but not the P-controller, and while in our model the rise starts at about 6% CO2 instead of 4% (as seen in Comroe, 1974, Fig. 5-1B), this is a function of parameters employed in the simulations where we did not attempt to fit the model behavior quantitatively to every single experimental observation. Nervertheless, the fundamental physiological issue here is the reason for the rise in minute ventilation, and our results provide a possible explanation for the first time: our model suggests that the sharp rise in minute ventilation is due to a PI-controller dynamics that fails to achieve steady-state in the system over a short period of time (of an order of minutes, as seen experimentally). We suggest that over this short time period, the system behaves as a PI-controller. Over a longer period of time however, the system does reach steady-state, so eventually other mechanisms (such as pulmonary stretch receptors inputs or processes with dynamics resembling leaky integrators) will operate.

The additional circulatory time delay did affect some aspects of the dynamic response of our model respiratory system. The time it took the system to respond once a stimulus was changed increased with the time delay and transient apneas were longer following hypoxia. The additional time delay also introduced transient and steady-state periodic breathing patterns. Furthermore, there was a notable difference in the dynamic response when the time delay was the same but from a different source. When the blood speed decreased (TL increased), apneas were longer, transient oscillations were larger in amplitude, and in the case of hypoxia, the rise in amplitude was slower as the system approached steady-state. An increased TL will clearly affect the values of pce and poe , but it remains to be studied why this leads to the observed difference in the dynamic response.

The responses to hypercapnia and hypoxia were also studied in Ben-Tal and Smith (2008) but without time delays, and while our conclusion here that a PI-controller is more consistent with experimental results is similar to the conclusion we reached in Ben-Tal and Smith (2008), it was nevertheless important to compare between PI- and P-controllers when time delays were included, particularly since complex dynamical behaviours such as periodic breathing can appear in the system when a P-controller with delays is used (as we now show in this paper). Furthermore, the nonlinearity of the model and dynamical complexity, including the fact that some inputs to the model are time dependent (the gas content in the blood is initialised every heart beat), makes it impossible to predict the dynamic as well as the steady-state responses of the system based on theoretical results from control theory. Even so, some of the results we found, such as the appearance of oscillations when the time delay or the controller gain were increased, and the fact that time delay may not affect or even shorten the time it takes to reach steady-state, can be found in simpler mathematical models of control systems that can be fully analyzed mathematically (see for example, Driver, 1977; Engelberg, 2005; Khoo, 2000; Kolmanovskii and Myshkis, 1992; MacDonald, 1989).

4.2 Appearance of periodic breathing

Our modeling results make two novel predictions: 1) that there could be two sources in the brainstem controller for the appearance of periodic breathing; and 2) that the dynamic process of the feedback mechanism is more important in some cases than circulatory time delays for the appearance of periodic breathing.

The source of periodic breathing in the brainstem controller has never been investigated before in a mathematical model because previous models that have been used to study periodic breathing did not distinguish between and incorporate explicit mechanisms for amplitude and frequency regulation. Our model incorporates separate mechanisms, based on our current understanding of the underlying neurobiological processes, for frequency and amplitude control, which is known to be a feature of the real system. We have illustrated that periodic breathing can result from the integrator-like amplitude control mechanism at the level of the VRG and also from the intrinsic dynamics of the pre-BötC that control frequency. This is an important observation since it predicts that there could be more than one mechanism for the appearance of periodic breathing, each associated with a different physiological condition.

Increased circulatory time delay clearly contributed to the appearance of periodic breathing patterns in our model but we have also shown that this is not a necessary structural feature to explain the phenomenon. We have shown that periodic breathing could appear in a PI-controller, representing the dynamic process of the feedback mechanism, under certain conditions even when there is no time delay. Furthermore, the appearance of periodic breathing was associated with a shortening of the length of the ventilatory afterdischarge in the PI-controller. Interestingly, the addition of time delay to a PI-controller did not cause transient periodic breathing patterns in response to hypoxia and hypercapnia (Figures 3 and 6) and the change in parameters of the PI-controller which cause the shortening of the length of ventilator afterdischarge, did not lead to the appearance of periodic breathing under hypercapnia (Figure 10 a)) all of which are consistent with experimental observations (Comroe, 1974). Our observation that time delay may not be a necessary structural feature to explain CSR is in agreement with other experiments reviewed in Quaranta et al. (1997).

4.3 Limitations of the model

Our current mathematical model integrates a simplified model of the lungs and a reduced representation of the brainstem neural control network. In particular, our model of rhythm generation is a simplification of how the pre-BötC inspiratory oscillator operates in the fully intact system including control of respiratory rhythm and pattern by other ponto-medullary respiratory circuits involved in inspiratory-expiratory phase switching (Smith et al., 2007). Also, the lung is modelled by a single compartment. The model we use in this paper represents a first step towards linking more structurally detailed models of the lungs and more neurobiologically detailed models of the brainstem control system. The predictions made by our model therefore need to be verified by more complex models and experiments. Nevertheless, our model of the oscillator retains a number of important features of more complex recent oscillator models such as the dynamic range of frequencies in response to input drives that are exhibited, for example, by the more complicated activity-type models (Rubin et al., 2009), and our model incorporates the important known neurobiological feature of separate mechanisms for frequency and amplitude control. Similarly, our lung model captures important features in the respiratory system such as lung mechanics and gas exchange and transport and could be linked in the future to more detailed models of the lungs (see for example, Tawhai and Ben-Tal, 2004).

Our study of the system responses to hypercapnia and hypoxia focused on amplitude control only. We chose this approach for two reasons. 1) The relative contributions of amplitude and frequency to the increase in minute ventilation in response to hypercapnia and hypoxia are highly variable – in some cases the increase in amplitude is more dominant while in other cases an increase in frequency is more significant (see Ben-Tal and Smith, 2008, Sec. 4.2, for more details). In addition, there is limited data that shows the dynamic response to hypercapnia and hypoxia. We compared the dynamic response of our model with the experiments described in Comroe (1974) in which the response of the amplitude and the frequency could be easily separated. We could therefore show that a PI-controller captures the amplitude response of these experiments qualitatively better than a P-controller. The minute ventilation response of CO2 produced by our model might be valid only in cases where the amplitude response is more dominant. Nevertheless, it showed a clear distinction between a P-controller and a PI-controller and provided a new explanation for the sharp rise in minute ventilation that could be tested experimentally. 2) As discussed above, our brainstem oscillator model is limited. Clearly more studies of a more realistically complex representation of the neural system model integrated with a lung model are needed, but it is possible that with separate frequency and amplitude control, the model output in terms of minute ventilation may be relatively insensitive to the details of the rhythm-generation clocking function, once the full dynamic range of frequency control is captured as with our oscillator model.

We studied the effect of a single time delay. That is, we chose the same time delay for both feedback functions of CO2 and O2. Other investigators (for example, Batzel and Tran, 2000; Khoo et al., 1982; Topor et al., 2007; Ursino et al., 2001) have chosen to distinguish between the time delays to peripheral and central chemoreceptors. The precise delays associated with activation and processing of peripheral vs. central chemoreceptor signals are currently not known, although the limited experimental data (Ponte and Purves, 1974), suggests that the activation delay alone for peripheral chemoreceptors is on the order of ~2 seconds, but this does not include downstream signal processing within the ponto-medullary controller circuitry. Response/processing delay times for central chemoreceptor signals, that could involve multiple distributed cellular transduction/signalling elements and circuit interactions (Feldman et al., 2003), would likely be longer. Our model allows for the inclusion of two different time delays, one that could represent the travel time to the chemosensitive areas in the brainstem (that are mainly sensitive to CO2) and another that could represent the shorter travel time to the peripheral chemoreceptors (that are mainly sensitive to O2). However, since information on the separate response dynamics of these two signalling systems is very limited, and since our study focused primarily on amplitude control we opted to study the effect of a single time delay. The effect of two time delays could be studied in the future when other issues of the neural control of breathing, such as basic mechanisms of amplitude and frequency control, and the dynamics of the different chemoreceptive processes themselves, have been resolved experimentally.

5 Acknowledgement

This research was supported by the Marsden Fund Council from Government funding, administered by the Royal Society of New Zealand and the Intramural Research Program of NIH, NINDS.

A Appendix: The key mathematical equations

A detailed description of the mathematical equations can be found in Ben-Tal (2006) and Ben-Tal and Smith (2008). Tables 1 and 2 below provide definitions of all the variables, parameters, and symbols. Values of the parameters are as shown in Tables 2 and 3 unless another value is given in the text. There are 9 variables in the mathematical model. These are described in the upper part of Table 1 and are shown on the left hand-side of equations (1)-(9) below. The other variables, described in the lower part of Table 1, are functions of the mentioned 9 variables and could therefore also change with time. Equations (1) and (2) below describe the brainstem pre-BötC oscillator. Eq. (3) describes the rate of change of muscle displacement. Equations (4)-(6) describe the rate of change of the alveolar pressure, and the alveolar concentrations of O2 and CO2. Equations (7)-(9) describe the rate of change of the blood partial pressures of O2 and CO2 and the rate of change of the blood concentration of .

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

where , , , , , , PL = ΔPL0 − kpxm, Pao = fo(PA − pw), Pac = fc(PA − pw), , , QA = q + Dc (pc − Pac)+ Do (po − pao) Note that when ΔPL0 is constant , see Eq. (4). Rp(t) is obtained by integrating numerically the signal A over one burst (see Ben-Tal and Smith, 2008 for more details). foi and fci depend on the lung dead space and air flow and will be affected by fom (respectively fcm) and fo(respectively fc). See Ben-Tal and Smith (2008) for more details.

Table 1. Variables of the mathematical model.

| Symbol | Meaning |

|---|---|

| A | Activity of the pre-BötC |

| hp | Inactivating gating of persistent sodium |

| xm | Muscle displacement |

| PA | Alveolar total pressure |

| fo | Concentration of O2 in alveoli |

| fc | Concentration of CO2 in alveoli |

| po | Blood partial pressure of O2 |

| pc | Blood partial pressure of CO2 |

| z | Concentration of |

| t | Time (independent variable) |

|

| |

| PL | Pleural pressure |

| pao | Alveolar partial pressure of O2 |

| pac | Alveolar partial pressure of CO2 |

| poe | Blood partial pressure of O2 at the end of the capillary |

| pce | Blood partial pressure of CO2 at the end of the capillary |

| Rp(t) | Ramp signal (phrenic activity) |

| foi | Inspired concentration of O2 |

| fci | Inspired concentration of CO2 |

| VA | Lung volume |

| q | Air flow through the airways |

| qi | Inspired air flow |

| Saturation function of hemoglobin | |

Table 2. Parameters of the mathematical model.

| Symbol | Meaning | Value (see Ben-Tal and Smith, 2008) |

|---|---|---|

| Activating rate constant of A | 133.33 s −1 | |

| Inactivating rate constant of A | 98 s −1 | |

| gn | Nominal value of the control parameter | 13.2 s −1 |

| Parameter affecting | 0.367 | |

| Parameter affecting h p | −0.033 | |

| Parameter affecting h p | 0.313 | |

| Parameter affecting h p | 0.04 | |

| Parameter affecting h p | 10 s | |

| Scaling parameter | 0.6667 | |

| Recoil rate constant of muscle | 0.212 | |

| k 1 | Conversion constant | 2 s −1 |

| k 2 | Conversion constant | 1 m s −1 |

| k p | Constant related to pleural pressure | 2.5 mmHg m −1 |

| Kn | Nominal value of the control parameter K | 0.5 |

| Δ PLO | Constant related to pleural pressure | 755.5 mmHg |

| Pm | Mouth total pressure | 760 mmHg |

| Pw | Vapour pressure of water at 37° C | 47 mmHg |

| por | Reference value of po in the control function | 104 mmHg |

| pcr | Reference value of pc in the control function | 40 mmHg |

| fom | Concentration of O2 in the month | 0.21 |

| fcm | Concentration of CO2 in the mouth | 0 |

| Vc | Capillaries volume | 0.07 l |

| R | Airways resistance to flow | 1 mmHg s l −1 |

| E | Lung elastance | 2.5 mmHg l −1 |

| TL | Time between heart beats | 60/72 s |

| Do | Diffusion capacity of O2 = 1.56 × 10−5 mol s−1 mmHg−1 |

3.5 × 10−4 l s −1 mmHg −1 |

| Dc | Diffusion capacity of CO2 = 3.16 ×10−5 mol s−1 mmHg−1 |

7.08 × 10−3 l s mmHg −1 |

| σ | Solubility of O2 in plasma | 1.4 × 10−6 mol l −1 mmHg −1 |

| σ c | Solubility of CO2 in plasma | 3.3 × 10−5 mol l mmHg −1 |

| Th | Concentration of haemoglobin molecule | 2 × 10−3 mol l −1 |

| h | Concentration of H+ | 10−7.4 mol l −1 |

| r 2 | Dehydration reaction rate | 0.12 s−1 |

| l 2 | Hydration reaction rate | 164 × 103 l s −1 mol −1 |

| δ | Acceleration rate | 101.9 |

and K are the two control parameters in the model and are described by the following feedback functions:

where:

We use Erc and Ero for convenience since then we can relate the feedback functions to standard controllers in control theory. In a P-controller the control parameter is proportional to an error and in an I-controller the parameter is proportional to an integral over an error. In engineering applications a reference value (such as pcr or por) is given explicitly. In a physiological application such a reference value is not given explicitly (Milhorn, 1966) but is there nevertheless implicitly since if a parameter K is proportional to Erc then where so it is possible to consider the parameter K as being proportional to pce. Similarly, if K is proportional to an integral over Erc (that is ) then so we can consider the rate of change of the parameter K as being proportional to pce.

Special cases of the feedback function studied in this paper are summarized in Table 3. In all the cases gn = 13.2 and K n = 0.5 .

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Batzel JJ, Kappel F, Schneditz D, Tran HT. Cardiovascular & Respiratory Systems: Modeling, Analysis & Control. Frontiers in Applied Mathematics. SIAM; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Batzel JJ, Tran HT. Modeling instability in the control system for human respiration: applications to infant non-REM sleep. Appl. Math. Comput. 2000;110:1–51. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Tal A. Simplified models for gas exchange in the human lungs. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 2006;238:474–495. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Tal A, Smith JC. A model for control of breathing in mammals: coupling neural dynamics to peripheral gas exchange and transport. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 2008;251:480–497. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2007.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comroe JH. Physiology of Respiration. 2nd Edition Year Book Medical Publishers, Inc.; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Driver RD. Ordinary and Delay Differential Equations. Springer-Verlag; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Eldridge FL. The North Carolina respiratory model. A multipurpose model for studying the control of breathing. In: Khoo MCK, editor. Bioengineering approaches to pulmonary physiology and medicine. Plenum Press; New York: 1996. pp. 25–49. [Google Scholar]

- Engelberg S. A mathematical introduction to control theory. Imperial College Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman JL, Del Negro CA. Looking for inspiration: new perspectives on respiratory rhythm. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2006;7:232–241. doi: 10.1038/nrn1871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman JL, Mitchell GS, Nattie EE. Breathing: rhythmicity, plasticity, chemosensitivity. Ann. Rev. Neurosci. 2003;26:239–266. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.26.041002.131103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler AC, Kalamangalam GP. Periodic breathing at high altitude. IMA J. Math. App. Med. 2002;19:293–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grodins FS, Buell J, Bart AJ. Mathematical analysis and digital simulation of the respiratory control system. J. Appl. Physiol. 1967;22(2):260–276. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1967.22.2.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan AS, Catcheside PG, Orr RS, O’Donoghue FJ, Saunders NA, McEvoy RD. Ventilatory decline after hypoxia and hypercapnia is not different between healthy young men and women. J. Appl. Physiol. 2000;88:3–9. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.88.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellogg RH. Central chemical regulation of respiration. In: Fenn WO, Rahn H, editors. Handbook of Physiology, Respiration Vol. I. American Physiological Society; Washington DC: 1964. pp. 507–534. [Google Scholar]

- Khoo MCK. Physiological Control Systems. Analysis, Simulation, and Estimation. IEEE Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Khoo MC, Kronauer RE, Strohl KP, Slutsky AS. Factors inducing periodic breathing in humans: a general model. J. Appl. Physiol. 1982;53(3):644–659. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1982.53.3.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoo MCK, Yamashiro SM. Models of control of breathing. In: Chang HA, Paiva M, editors. Respiratory Physiology: An Analytical Approach. Mercer Dekker; New York: 1989. pp. 799–829. [Google Scholar]

- Kolmanovskii V, Myshkis A. Applied Theory of Functional Differential Equations. Kluwer Academic Publishing; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Lange RL, Horgan JD, Botticelli JT, Tsagaris T, Carlisle RP, Kuida H. Pulmonary to arterial circulatory transfer function: importance in respiratory control. J. Appl. Physiol. 1966;21(4):1281–1291. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1966.21.4.1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu K, Clark JW, Jr, Ghorbel FH, Ware DL, Zwischenberger JB, Bidani A. Whole-body gas exchange in human predicted by a cardiopulmonary model. Cardiovascular Engineering. 2002;3(1):1–19. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald N. Biological delay systems: linear stability theory. Cambridge University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Mackey MC, Glass L. Oscillation and chaos in physiological control systems. Science. 1977;197:287–289. doi: 10.1126/science.267326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milhorn HT., Jr . The application of control theory to physiological systems. W. B. Saunders Company; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Milhorn HT, Jr, Guyton AC. An analog computer analysis of Cheyne-Stokes breathing. J. Appl. Physiol. 1965;20(2):328–333. [Google Scholar]

- Ponte J, Purves MJ. J. Appl. Physiol. 1974;37(5):635–647. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1974.37.5.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quaranta AJ, D’Alonzo GE, Krachman SL. Cheyne-stokes respiration during sleep in congestive heart failure. Chest. 1997;111:467–473. doi: 10.1378/chest.111.2.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin JE, Shevtsova NA, Ermentrout GB, Smith JC, Rybak IA. Multiple rhythmic states in a model of the respiratory CPG. J. Neurophysiol. 2009;101:2146–2165. doi: 10.1152/jn.90958.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JC, Abdala APL, Koizumi H, Rybak IA, Paton JFR. Spatial and functional architecture of the mammalian brainstem respiratory network: a hierarchy of three oscillatory mechanisms. J. Neurophysiol. 2007;98:3370–3387. doi: 10.1152/jn.00985.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JC, Butera RJ, Koshiya N, Negro CD, Wilson CG, Johnson SM. Respiratory rhythm generation in neonatal and adult mammals: The hybrid pacemaker-network model. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2000;122:131–147. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(00)00155-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JC, Ellenberger HH, Ballanyi K, Richter DW, Feldman JL. Pre-Bötzinger complex: A brainstem region that may generate respiratory rhythm in mammals. Science. 1991;254:726–729. doi: 10.1126/science.1683005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tawhai M, Ben-Tal A. Multiscale modelling for the Lung Physiome. Cardiovascular Engineering. 2004;4(1):19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Topor ZL, Vasilakos K, Younes M, Remmers JE. Model based analysis of sleep disordered breathing in congestive heart failure. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2007;155:82–92. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2006.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ursino M, Magosso E, Avanzolini G. An integrated model of the human ventilatory control system: the response to hypercapnia. Clin. Physiol. 2001;21(4):447–464. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2281.2001.00349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]