Abstract

Despite the use of cholinergic therapies in Alzheimer’s disease and the development of cholinergic strategies for schizophrenia, relatively little is known about how the system modulates the connectivity and structure of large-scale brain networks. To better understand how nicotinic cholinergic systems alter these networks, this study examined the effects of nicotine on measures of whole-brain network communication efficiency. Resting-state fMRI was acquired from fifteen healthy subjects before and after the application of nicotine or placebo transdermal patches in a single blind, crossover design. Data, which were previously examined for default network activity, were analyzed with network topology techniques to measure changes in the communication efficiency of whole-brain networks. Nicotine significantly increased local efficiency, a parameter that estimates the network’s tolerance to local errors in communication. Nicotine also significantly enhanced the regional efficiency of limbic and paralimbic areas of the brain, areas which are especially altered in diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease and schizophrenia. These changes in network topology may be one mechanism by which cholinergic therapies improve brain function.

Keywords: nicotine, acetylcholine, graph theory, small-world, network, fMRI

Introduction

The cholinergic system modulates key cognitive functions, including attention, learning and memory (Wallace & Porter, 2011). Dysfunction of the system plays a central role in common psychiatric and neurologic diseases, most notably in Alzheimer’s disease (Geula & Mesulam, 1996). Recent research also points to cholinergic dysfunction in schizophrenia (Martin & Freedman, 2007) Given its role in disease states, and its widespread role in healthy brain function a more complete understanding of the neurobiology of cholinergic systems is needed.

The cholinergic system has complex features that are not confined to single region, but are distributed throughout the cortex. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChR) are found in all areas of the cortex and the limbic system. Cholinergic fibers, originating in the nucleus basalis, project to all areas of the cortex and especially to limbic and paralimbic areas (Mesulam & Geula, 1988). In addition to this global system of projections, interneurons responding to nAChR stimulation are found throughout the cortex and provide localized control of neural activity (Xiang, Huguenard, & Prince, 1998). This anatomical organization suggests that the cholinergic system is ideally situated to provide both local and global modulation of cortical networks and information processing.

Indeed, evidence suggests that cholinergic mechanisms modulate networks that are critical for healthy cognitive function and are vulnerable to disruption. For example, selective attention, which is mediated by a widespread network of frontal, posterior parietal and cingulate cortical regions (Ansado, Monchi, Ennabil, Faure, & Joanette, 2012), is impaired in many neuropsychiatric illnesses (Barr et al., 2007; Festa, Heindel, & Ott, 2010; Levin et al., 1996). The cholinergic system is a key mediator within the neurocircuitry of attention (Wallace & Porter, 2011). Pharmacologic enhancement of the system improves attention in animal models (Hahn, Shoaib, & Stolerman, 2011) and disease states (Barr et al., 2007; Levin et al., 1996). Similarly, sensory gating, the process by which the brain filters incoming sensory information, is mediated by a widespread network of regions including the superior temporal gyrus, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, insula, and hippocampus (Bak, Glenthoj, Rostrup, Larsson, & Oranje, 2011). The process is disrupted in disease and improved with cholinergic treatments (L. Adler, Hoffer, Wiser, & Freedman, 1993).

Despite evidence for cholinergic effects on large-scale brain networks, little is known about the mechanisms by which these effects occur. In order to better understand these network dynamics, certain characteristics of networks can be translated into mathematical models. New analytic techniques now allow hypothesis testing involving large-scale brain networks, which can be used to improve our understanding of cholinergic mechanisms.

Recent advances in the field of complex network theory have led to a focus on the ‘small-world’ topology (Watts & Strogatz, 1998). The small-world model conceptualizes the brain as a distributed, massively-multiparallel system that processes information both globally and locally. In this view, large-scale neural networks are optimized for both global integration and local specialization, all while minimizing the energy and resources involved in constructing the network (Latora & Marchiori, 2003). It allows for global features such as non-localized pathology in disease and the widespread projections of the cholinergic system. It also includes localized features, by treating individual brain regions as processing nodes that interact with nearby regions as well as with the whole network. Pathology and dysfunction manifest as abnormal network parameters, typically associated with inefficiency and an increased cost. For example, neural networks in schizophrenia require more connections between nodes to achieve a level of network integration equivalent to that of controls (Liu et al., 2008).

To better understand the system-wide effects of nicotinic cholinergic systems within the brain, we used network analysis techniques to examine network topology in an fMRI study of the nicotinic cholinergic receptor agonist nicotine, as compared to placebo administration, in healthy subjects. This data set was used in a previous analysis of the effect of nicotine on default mode network activity (Tanabe et al., 2011). For this study, we hypothesized that nicotine would improve resting state measures of network efficiency. In addition, we hypothesized that limbic/paralimbic regions that have been shown to be particularly altered in disease states would show improved local efficiency, i.e. enhanced interaction with all other brain regions, in response to nicotine.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Subjects

Fifteen healthy adults participated in the study, 9 men and 6 women (average age of 29.4 years, SD 7.5). All subjects were non-smokers, 10 had never smoked, while 5 had minimal previous tobacco use. Subjects were excluded for axis I disorders, neurologic illness, or major medical illness. No subject had a lifetime use of more than 100 cigarettes and all were nicotine-free for at least 3 years prior to the study. Subjects provided written informed consent as approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutions Review Board.

2.2 Experimental Design and Nicotine Administration

A single-blinded, placebo-controlled, cross-over design was used. Details have been provided previously (Tanabe et al., 2011). Briefly, subjects participated in three sessions. During the first session medical, psychiatric and smoking history were obtained and subjects underwent a nicotine tolerance test. During the second and third sessions, subjects were scanned before and after receiving either a 7 mg transdermal nicotine patch (Nicoderm CQ, Alza Corp) covered in tape or the placebo treatment. Subjects were re-scanned 90 minutes after receiving the patch or placebo, when nicotine levels from the transdermal patch were expected to peak (Fant, Henningfield, Shiffman, Strahs, & Reitberg, 2000). Heart rate was measured before and during scanning by an MR-compatible photoplethysmopraph, with a sampling frequency of 40 Hz. As reported previously (Tanabe et al., 2011), no effects of drug on heart rate were observed.

2.3 fMRI Data Acquisition & Preprocessing

Resting state images were acquired on a 3T whole-body MR scanner (General Electric, Milwaukee, Wl, USA) using a standard quadrature head coil. A high-resolution 3D T1 -weighted anatomical scan was collected. Functional scans were acquired with the following parameters: TR 2000 ms, TE 32 ms, FOV 240 mm2, matrix size 64 × 64, voxel size 3.75 × 3.75 mm2, slice thickness 3 mm, gap 0.5 mm, interleaved, flip angle 70 degrees. Resting fMRI scan duration was 10 min, with subjects instructed to rest with eyes closed. Data were preprocessed using SPM8 (Wellcome Dept. of Imaging Neuroscience, London, UK) in Matlab 2009b. All subjects had less than 2 mm of movement. The first four images were excluded for saturation effects. Images were realigned to the first volume and normalized to the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space.

2.4 Anatomical Parcellation

Volumes were separated into regions of interest using the Anatomical Automatic Labeling (AAL) templates (Tzourio-Mazoyer et al., 2002). This parcellation divides each hemisphere into 45 cortical and subcortical regions, for a total of 90 regions. All areas were labeled by functional zones as described in Mesulam (Mesulam, 1998). Time series were extracted by averaging the BOLD signal over all the voxels in a region for each time point. These regional mean time series were used for wavelet decomposition and correlation.

2.5 Wavelet Correlation Analysis

We applied the maximal overlap discrete wavelet transform (MODWT) over the first four scales to each regional mean time series. For each pair of time series we measured the correlation between wavelet coefficients at each scale. This resulted in a set of four 90 × 90 correlation matrices for each subject. Resting state functional connectivity is typically greatest at low frequencies, while non-neural sources of regional correlation are typically represented at higher frequencies (Cordes et al., 2001). The frequency range of the kth scale of the wavelet decomposition is [2(−k−1)/TR, 2(−k)/TR] (Percival & Walden, 2006). Based on the results of previous studies (Ginestet & Simmons, 2011; 2011; Supekar, Menon, Rubin, Musen, & Greicius, 2008), the 4th scale, corresponding to the frequency interval of [0.01, 0.03] Hz was used for further network analysis. The mean correlation coefficient, the averaged wavelet coefficient for a correlation matrix, was used as a global measure of functional connectivity.

2.6 Statistical Parametric Networks (SPNs)

Visual representations of brain networks were created as in Ginestet and Simmons, 2011. Following their terminology, we use ‘statistical parametric networks’ (SPNs) to denote these graphs. Mean SPNs represent the mean functional network of the population of subjects for the conditions of the experiment. Differential SPNs were created as well as in Ginestet and Simmons, 2011, but no edge survived correction for multiple comparisons. Mean SPNs were created as detailed previously (Ginestet & Simmons, 2011). Briefly, condition mean correlation coefficients were Fisher z-transformed, standardized to the grand sample mean and grand sample standard deviation, and used in a one-sample location test against a significance level determined by the false discovery rate (FDR), with a base FDR of q=0.05. This identified connections that were significantly stronger than the grand sample mean.

2.7 Network Topology Measures

Standard graph-theoretical measures were used to compare the organization of networks across conditions. Formally, a graph G is defined as a set of vertices {V} connected by a set of edges {E}. The term ‘node’ is often used interchangeably with vertex and here will be used when referring to specific regions of the brain, while vertex is used in this section’s notation. The degree of a vertex is the number of edges connecting it to other vertices. The total number of vertices and edges of a graph are denoted Nv and NE and defined by Nv:= |V| and NE:= |E|, where |.| indicates the number of elements in the set. Here, a vertex is an anatomical region and Nv = 90. The total number of possible edges in a saturated graph can be calculated from this by NE = Nv * (Nv − 1)/2 = 4005. Which specific connections between regions will be used as edges in the following calculations will be addressed below.

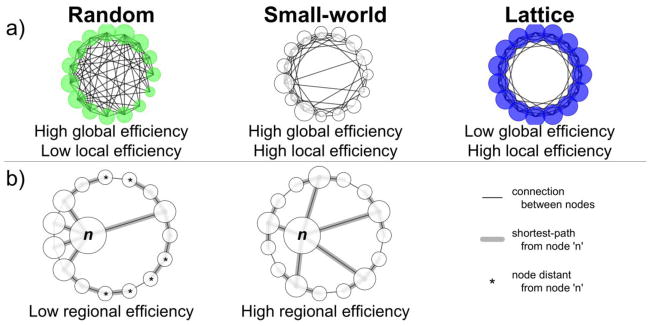

Global and local efficiencies are measures of network topology (Figure 1a) and are related to theoretical information transfer within a network (Latora & Marchiori, 2003). Both are similar to other small-world measures in graph theory, but more directly relate to information processing within a network. Global efficiency measures how integrated the entire network is; that is the efficiency of information transfer throughout the entire network. Local efficiency measures the network’s capacity for regional specialization, by looking at how well connected its sub-networks are. Additionally, it provides an estimate of fault tolerance, since an abundance of local connections allows the network to route around damage to vertices or edges. Both measures derive from a single equation that describes the efficiency of any network in terms of the inverse of the harmonic mean of the minimum path length:

| (1) |

where dij is the shortest path between vertices i & j, and the set {J ≠ i ∈ V} is the set of all vertices in {V} that are different from i. Global efficiency is then defined as the efficiency of the entire network:

| (2) |

Figure 1.

Network topology examples, a) Random networks, with randomly determined connections, have high global efficiency, as shown by the many connections crossing the center of the graph, and low local efficiency, as shown by the relatively few connections between nearby nodes. Lattice networks show the reverse pattern. Small-world networks are intermediate, with properties of both, b) Regional efficiency. Both networks have an identical number of nodes and connections, with only small differences in their topology. Left: The regional efficiency of node ‘n’ is low due to the many connections separating it from the nodes marked with asterisks. Communication between n and these nodes will be inefficient. Right: The regional efficiency of n is improved by redistributing its connections. All nodes are now relatively close to node n, allowing for efficient communication between it and all other areas of the network.

Local efficiency is related to the average efficiency of the subnetworks. Let Gi indicate a subnetwork containing all vertices that are neighbors of the ith vertex; ie, V(Gi) = {vj ∈ G | vj ~ vi}, where vj ~ vi indicate that the ith and jth vertices are connected. Local efficiency is then defined as the averaged efficiencies of all subnetworks Gi:

| (3) |

Regional efficiency, sometimes referred to as nodal efficiency, is a measure of how connected a specific vertex is to all other vertices in the network (Figure 1b, (He et al., 2009)). The regional efficiency for vertex v is defined as the inverse of the harmonic mean of the minimum path length between an index vertex and all other vertices in the network:

| (4) |

Of note, the average of all regional efficiencies is the global efficiency since .

The cost or sparsity of a network is defined as the fraction of edges in a network compared to a saturated network with the same number of nodes.

A network has a small-world topology if its properties are midway between comparable networks with either random or regular lattice topologies (Watts & Strogatz, 1998). This definition, while imprecise, qualitatively captures the usefulness of the small-world model, with its ability to encompass the properties of two very different types of network topology. A comparable random network has the same number of vertices and edges, but the connections between nodes are randomly determined. A comparable regular lattice has the same number of vertices and edges, but its connections are distributed evenly to neighboring vertices. Random networks have high global efficiency but low local efficiency, whereas lattice networks have low global efficiency but high local efficiency. Small-world networks have higher global efficiency than a comparable lattice network and higher local efficiency than a comparable random network (Latora & Marchiori, 2003). Regular and lattice networks were generated over the full range of possible costs then compared to brain networks with equal costs.

Previous studies using network topology in the neurosciences have used either thresholding or cost-based functions to determine which correlations are relevant edges. However, there is no definitive way to select a threshold or cost value and the choice of arbitrary values can bias results (Ginestet, Nichols, Bullmore, & Simmons, 2011). Instead, we use cost-integrated versions of global, local and regional efficiencies (ĒGlobal, ĒLocal, ĒRegional) evaluate a network’s efficiency independently from the correlation strength of its edges, where the efficiency function is integrated over the full range of possible cost values, [0, 1] (Ginestet & Simmons, 2011; He et al., 2009; 2009).

2.8 Network Topology Statistics

To assess the hypothesized interaction of drug (placebo versus nicotine) by session (pre- versus post-patch), we computed a paired t-test on the subtraction of the pre- from the post data (equivalent to the interaction term in a 2 × 2 repeated measures ANOVA). Type I errors in multiple comparison testing were controlled using the false discovery rate (FDR) technique with a base of q = 0.05 (Benjamini, 2001). All analysis were carried out in the R statistical programming language (http://www.r-project.org) using the base installation and the packages ‘Brainwaver,’ ‘waveslim,’ ‘igraph,’ and ‘NetworkAnalysis;’ available in the Comprehensive R Archive Network (http://cran.r-project.org).

3. Results

3.1 Statistical Parametric Networks

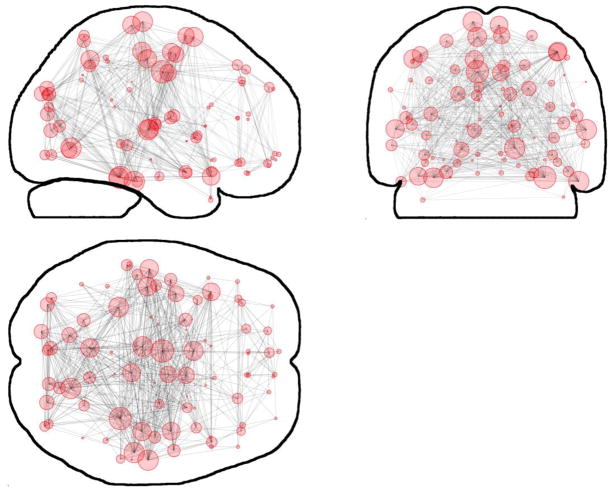

Nicotine, as compared to placebo, did not change mean correlation coefficient (t = −1.064, p = 0.305). A mean Statistical Parametric Network (SPN), which represents the connection patterns and nodal degrees for the whole-brain, is shown in Figure 2. No significant differences between drug conditions were observed. The pattern of connections in all cases showed prominent bilateral connections with a prominent symmetry in the degree distribution, with identical nodes in either hemisphere having similar degrees.

Figure 2.

Mean SPN for the post-placebo condition as an example of a whole-brain network. Glass-brain layout, circles represent nodes and their size proportional to nodal degree. No significant differences between experimental conditions were observed.

3.2 The Efficient Small-world of Functional Brain Networks

The functional networks in all experimental conditions showed small-world properties. The networks were intermediate between simulated networks with a random topology, which have a high global efficiency and a low local efficiency, and those in simulated networks with a lattice topology, which have low global but high local efficiency (Figure 3). This was particularly true for values in the small-world regime of cost = 0.1 to 0.3 (Liu et al., 2008). Both global & local efficiencies in all functional networks started low and rose rapidly with small increases in cost. At very low cost values, all networks were closer to a lattice topology with relatively low global efficiency and relatively high local efficiency. As cost increased all networks approached a random topology, with relatively high global efficiency.

Figure 3.

Small-world properties of brain networks. For all conditions and costs, local and global efficiencies were intermediate between simulated random and lattice networks.

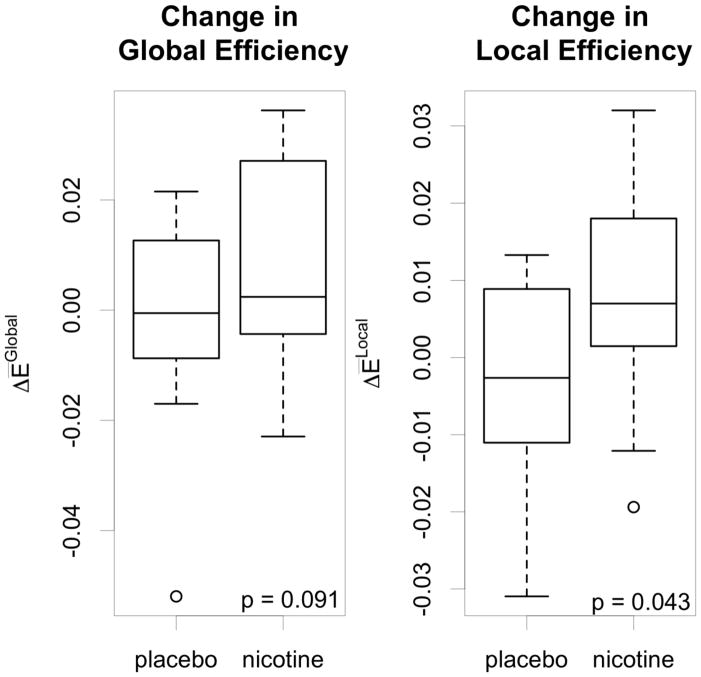

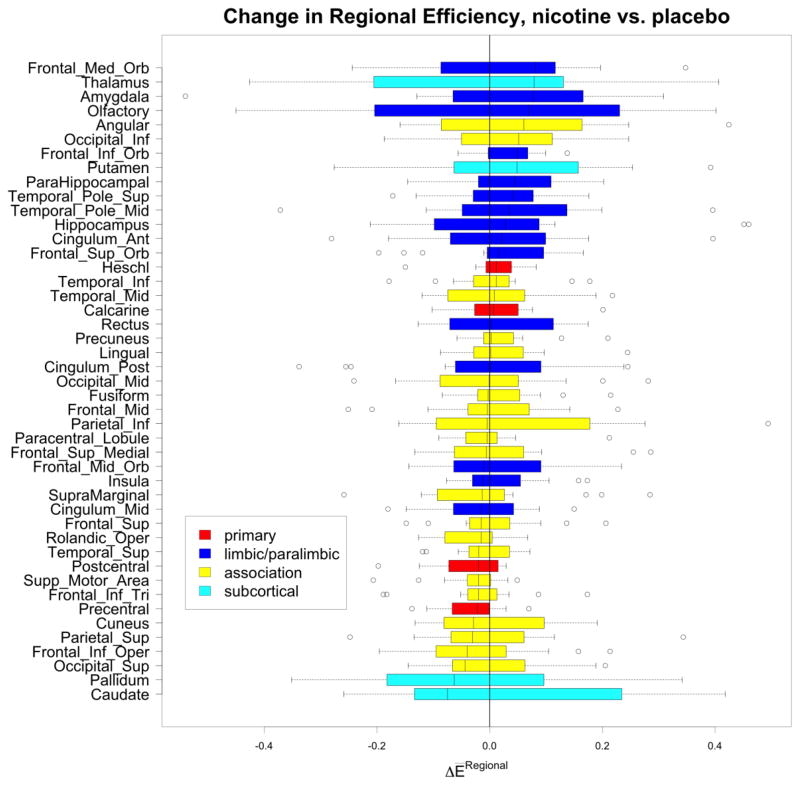

3.3 Nicotine Increased Network Efficiencies

Nicotine administration, compared to placebo, significantly increased cost-integrated local efficiency of the network (Figure 4, t = 2.23, p = 0.043). A trend for cost-integrated global efficiency also was observed (Figure 5, t = 1.82, p = 0.091). Regional efficiencies also were examined to determine which areas of the brain contributed most to the changes in network efficiencies. Changes in cost-integrated regional efficiency for each region, averaged between hemispheres, are displayed in Figure 5. For most regions, nicotine administration resulted in modest changes of regional efficiency of less than ten percent. Primary sensorimotor areas showed the least amount of change. Association areas showed a greater range of responses to nicotine, with both increases and decreases. Subcortical areas had widely varying responses, with the thalamus and putamen increasing their regional efficiencies while other areas of the basal ganglia had the largest decrease. Overall, none of these areas significantly changed in response to nicotine, compared to placebo, either individually or grouped by cortex type, and no laterality was evident in the responses. In grouping regions as either prefrontal, sensorimotor, association, subcortical, or limbic/paralimbic (Mesulam, 1998); nicotine, as compared to placebo, was associated with a significant increase in cost-integrated regional efficiency for the limbic and paralimbic areas (Wilcoxon signed rank test on medians, H0 as above, V = 108, p = 0.0043). This effect was more pronounced on the right side compared to the left (Wilcoxon signed rank test on medians with H0: no change in response to treatment: right V = 102, p = 0.0151, left V = 72, p = 0.52).

Figure 4.

Nicotine-associated changes in global and local efficiencies. Nicotine, compared to placebo, significantly increased local efficiency. A trend towards increased global efficiency also was observed.

Figure 5.

Changes in regional efficiencies for each AAL region, averaged across hemispheres. Limbic and paralimbic areas showed increased regional efficiencies in response to nicotine as compared to placebo.

4. Discussion

This study used wavelet analysis and network theory to investigate how nicotine alters functional networks within the brain. The primary findings were: 1) No effect on average connectivity or on SPNs was observed. 2) Network topologic measures showed a significant increase in local efficiency, a trend towards increased global efficiency, and a significant increase in the regional efficiency of limbic and paralimbic areas. These results suggest that nicotine influences cognition by improving the efficiency of information transfer within the brain on both global and local levels, particularly by increasing the integration of information in limbic and paralimbic areas within the brain’s network. These results are relevant to our understanding of the large-scale networks that mediate cognition and for diseases that involve nicotinic cholinergic pathology.

4.1 Cholinergic Effects on Network Topology

Nicotine administration improves cognitive, electrophysiological, and hemodynamic measures of neuronal function in many disease states, particularly Alzheimer’s disease (Festa et al., 2010) and schizophrenia (L. Adler et al., 1993; Barr et al., 2007). Attention, working memory, episodic memory and sensory gating are all fundamental cognitive functions that are disrupted in these diseases and improved by cholinergic agonists (L. Adler et al., 1993; Barr et al., 2007; Festa et al., 2010). All of these cognitive functions are mediated by networks of connected regions within the brain.

A main finding of this study was that nicotine increased local efficiency. A very similar network measure, clustering coefficient, has been shown to be associated with higher performance on many cognitive tests in healthy subjects: It positively correlates with measures of attention, working memory, verbal & spatial memory and psychomotor speed (Douw et al., 2011). Part of nicotine’s effect on cognition could be due to modifying the exchange of information within the networks that mediate these functions. A possible mechanism for this effect may involve nicotinic receptors that are found on interneurons throughout the cortex. Nicotinic receptor agonists have been shown to synchronize interneuron activity (Bandyopadhyay, 2006). Through these interneurons, cholinergic agonists decrease the surround inhibition of neurons and enhance intracolumnar inhibition (Xiang et al., 1998). Cholinergic activity promotes information transfer by enhancing the influence of afferent inputs (Kimura, 2000) or facilitating ‘neuronal avalanches’ that convey information across cellular networks (Pasquale, Massobrio, Bologna, Chiappalone, & Martinoia, 2008). Any or all of these mechanisms could contribute to the network efficiency changes observed in the present study.

4.2 Disrupted Network Topology in Schizophrenia

In addition to its association with poorer cognitive function in healthy individuals, inefficient network topology also has been shown in schizophrenia. Which network feature is disrupted is dependent on the type of network (ie, anatomical or functional), but overall, studies typically have found decreased global integration and local specialization. In functional networks studied with fMRI (Alexander-Bloch et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2008; Lynall et al., 2010) or EEG (Micheloyannis et al., 2006; Rubinov et al., 2009), schizophrenia has been associated with decreased local specialization, measured as either local efficiency or the conceptually similar clustering coefficient. Anatomical networks constructed with diffusion tensor tractography (DTI) also found decreases in local efficiency, but show decreases in global efficiency as well (Q. Wang et al., 2012; Zalesky et al., 2011). Both local and global efficiency have been shown to negatively correlate with duration of illness (Liu et al., 2008). Clustering coefficient has been shown to positively correlate with medication dosage (Rubinov et al., 2009). In structural networks, local and global efficiency negatively correlate with scores on the Positive and Negative Symptom Scale (PANSS, (Q. Wang et al., 2012)). All together, reductions in network measures of local specialization, along with symptom correlations, suggest that schizophrenia is associated with a subtle randomization of connection patterns within the brain. Nicotine’s ability to increase local efficiency shown in the present study suggests, therefore, that cholinergic enhancement may be a potential therapeutic mechanism in the illness.

4.3 Disrupted Network Topology in Alzheimer’s Disease

Abnormal network topology also has been shown in Alzheimer’s disease. Much like in schizophrenia, the network measure disrupted depends on the type of network and the experimental modality used. Functional networks studied with fMRI have found a decreased measure conceptually similar to local efficiency, the clustering coefficient (Supekar et al., 2008). In functional networks measured by EEG or MEG, the clustering coefficient was decreased while the characteristic path length, approximately the inverse of global efficiency, was increased (Stam et al., 2008; Stam, Jones, Nolte, Breakspear, & Scheltens, 2006).

In summary, functional networks in Alzheimer’s disease have shown decreased local specialization and decreased global integration. These changes suggest that functional networks in Alzheimer’s disease have a more randomized structure, relative to those observed in healthy individuals. Nicotine’s ability to increase local efficiency in functional networks, shown in the present study, may contribute to the efficacy of cholinergic agonists used in treating Alzheimer’s disease.

4.4 Paralimbic and Limbic Regional Efficiency Effects

The present study suggests that nicotine increases regional efficiency in limbic and paralimbic areas, thereby promoting information exchange between these areas and the rest of the brain. This effect also may be particularly relevant to disease states. Schizophrenia has been associated with grey matter deficits in these regions (Ellison-Wright & Bullmore, 2010). In particular, temporal pole grey matter volume negatively correlates with hallucinations and delusions in the disease (Crespo-Facorro et al., 2004). These deficits extend to the superficial white matter associated with the paralimbic regions (Makris et al., 2010). On the cellular level, limbic and paralimbic areas in schizophrenia have decreased neuron and interneuron counts (Kreczmanski et al., 2007; A. Y. Wang et al., 2011) and decreased nicotinic receptor concentrations (Freedman, Hall, Adler, & Leonard, 1995). In terms of functional physiology, schizophrenia has been associated with decreased activation of the amygdala, orbitofrontal cortex, and anterior cingulate gyrus as measured with fMRI using an oddball paradigm (Liddle, Laurens, Kiehl, & Ngan, 2006). By increasing the regional efficiency of these regions, nicotine could act to improve information processing of limbic and paralimbic areas in schizophrenia.

Alzheimer’s disease also is characterized by prominent deficits in limbic and paralimbic regions. The temporal pole, insula, orbitofrontal cortex and hippocampus are all atrophied and show decreases in cholinergic fibers (Geula & Mesulam, 1996; 1996; Halliday, Double, Macdonald, & Kril, 2003). The hippocampus, amygdala and anterior cingulate cortex all show decreased perfusion and metabolism (David Callen, Black, & Caldwell, 2002; Nestor, Fryer, Smielewski, & Hodges, 2003). Similarly, limbic and paralimbic areas show decreases in grey matter (DJ Callen, Black, Gao, Caldwell, & Szalai, 2001; Frisoni, 2005; Thompson et al., 2003). Nicotine’s ability to increase the regional network efficiency of these areas observed in the present study may mediate its cognitive effects in Alzheimer’s disease, and suggests a possible mechanism for therapeutic cholinergic effects in the disease.

4.5 Limitations

This study used the anatomical AAL atlas (Tzourio-Mazoyer et al., 2002) to parcellate grey matter into distinct regions, then average the signal of all voxels within each region to obtain time series for further correlation and network analysis. Because the relationship between anatomical and functional anatomies is not precisely known, some of the regional boundaries in the atlas may be arbitrary and some functional subdivisions may not be included. Any networks created from this method are necessarily approximations of brain function (Smith, 2012). However, since the same anatomical atlas was used throughout this study, all measured network parameters can be reliably compared across conditions (Zalesky et al., 2010).

Physiological noise is another potential confounding factor in studies of functional connectivity. As reported in a previous analysis of this data set (Tanabe et al., 2011), heart rate was not significantly changed in response to nicotine administration. From this, it is unlikely that these network changes resulted from this source of noise. Respiration rate was not measured and cannot be ruled out. However, previous work has shown that both respiratory and cardiac effects are primarily found at higher frequency ranges than were examined in this study (Cordes et al., 2001).

5. Conclusion

Nicotine significantly improves network local efficiency with a trend towards improving global efficiency, and improves regional efficiencies in limbic and paralimbic regions. These measures of network topology are abnormal in schizophrenia and Alzheimer’s disease, both of which show deficits in nicotinic cholinergic systems. This effect not only improves our understanding of the mechanism of cholinergic effects on network topology, but points to a possible explanation for some of the positive therapeutic effects of cholinergic agonism in the diseases.

Acknowledgments

The research was supported by the VA Biomedical Laboratory and Clinical Science Research and Development Service, the National Association for Research in Schizophrenia and Affective Disorders (NARSAD), the Blowitz-Ridgeway Foundation, NIH/NIDDK R01 DK089095 and NIH/NIMH P50 MH-086383.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adler L, Hoffer L, Wiser A, Freedman R. Normalization of auditory physiology by cigarette smoking in schizophrenic patients. The American journal of psychiatry. 1993;150(12):1856–61. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.12.1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander-Bloch AF, Gogtay N, Meunier D, Birn R, Clasen L, Lalonde F, Lenroot R, et al. Disrupted Modularity and Local Connectivity of Brain Functional Networks in Childhood-Onset Schizophrenia. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience. 2010;4 doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2010.00147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansado J, Monchi O, Ennabil N, Faure S, Joanette Y. Load-dependent posterior–anterior shift in aging in complex visual selective attention situations. Brain Research. 2012;1454:14–22. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.02.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bak N, Glenthoj BY, Rostrup E, Larsson HB, Oranje B. Source localization of sensory gating: A combined EEG and fMRI study in healthy volunteers. NeuroImage. 2011;54(4):2711–2718. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandyopadhyay S. Endogenous Acetylcholine Enhances Synchronized Interneuron Activity in Rat Neocortex. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2006;95(3):1908–1916. doi: 10.1152/jn.00881.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr RS, Culhane MA, Jubelt LE, Mufti RS, Dyer MA, Weiss AP, Deckersbach T, et al. The Effects of Transdermal Nicotine on Cognition in Nonsmokers with Schizophrenia and Nonpsychiatric Controls. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;33(3):480–490. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp. 1301423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y. The control of the false discovery rate in multiple testing under dependency. Annals of statistics 2001 [Google Scholar]

- Callen David Black S, Caldwell C. Limbic system perfusion in Alzheimer’s disease measured by MRI-coregistered HMPAO SPET. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 2002;29(7):899–906. doi: 10.1007/S00259-002-0816-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callen DJ, Black S, Gao F, Caldwell C, Szalai J. Beyond the hippocampus: MRI volumetry confirms widespread limbic atrophy in AD. Neurology. 2001;57(9):1669–74. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.9.1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordes D, Haughton V, Arfanakis K, Carew J, Turski P, Moritz C, Quigley M, et al. Frequencies contributing to functional connectivity in the cerebral cortex in “resting-state” data. AJNR American journal of neuroradiology. 2001;22(7):1326–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespo-Facorro B, Nopoulos PC, Chemerinski E, Kim J-J, Andreasen NC, Magnotta V. Temporal pole morphology and psychopathology in males with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. 2004;132(2):107–115. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douw L, Schoonheim MM, Landi D, van der Meer ML, Geurts JJG, Reijneveld JC, Klein M, et al. Cognition is related to resting-state small-world network topology: an magnetoencephalographic study. Neuroscience. 2011;175:169–177. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison-Wright I, Bullmore E. Anatomy of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia: A meta-analysis. Schizophrenia Research. 2010;117(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fant R, Henningfield J, Shiffman S, Strahs K, Reitberg D. A pharmacokinetic crossover study to compare the absorption characteristics of three transdermal nicotine patches. Pharmacology, biochemistry, and behavior. 2000;67(3):479–82. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00399-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festa EK, Heindel WC, Ott BR. Dual-task conditions modulate the efficiency of selective attention mechanisms in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychologia. 2010;48(11):3252–3261. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman R, Hall M, Adler LE, Leonard S. Evidence in postmortem brain tissue for decreased numbers of hippocampal nicotinic receptors in schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry. 1995;38(1):22–33. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(94)00252-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisoni GB. Structural correlates of early and late onset Alzheimer’s disease: voxel based morphometric study. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 2005;76(1):112–114. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2003.029876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geula C, Mesulam M. Systematic regional variations in the loss of cortical cholinergic fibers in Alzheimer’s disease. Cerebral cortex (New York, NY: 1991) 1996;6(2):165–77. doi: 10.1093/cercor/6.2.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginestet CE, Simmons A. Statistical parametric network analysis of functional connectivity dynamics during a working memory task. NeuroImage. 2011;55(2):688–704. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginestet CE, Nichols TE, Bullmore ET, Simmons A. Brain network analysis: separating cost from topology using cost-integration. PloS one. 2011;6(7):e21570. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn B, Shoaib M, Stolerman IP. Selective nicotinic receptor antagonists: effects on attention and nicotine-induced attentional enhancement. Psychopharmacology. 2011;217(1):75–82. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2258-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliday G, Double K, Macdonald V, Kril J. Identifying severely atrophic cortical subregions in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiology of aging. 2003;24(6):797–806. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00227-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y, Dagher A, Chen Z, Charil A, Zijdenbos A, Worsley K, Evans A. Impaired small-world efficiency in structural cortical networks in multiple sclerosis associated with white matter lesion load. Brain: a journal of neurology. 2009;132(12):3366–3379. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura F. Cholinergic modulation of cortical function: a hypothetical role in shifting the dynamics in cortical network. Neuroscience research. 2000;38(1):19–26. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(00)00151-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreczmanski P, Heinsen H, Mantua V, Woltersdorf F, Masson T, Ulfig N, Schmidt-Kastner R, et al. Volume, neuron density and total neuron number in five subcortical regions in schizophrenia. Brain: a journal of neurology. 2007;130(3):678–692. doi: 10.1093/brain/aw1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latora V, Marchiori M. Economic small-world behavior in weighted networks. The European Physical Journal B-Condensed… 2003 [Google Scholar]

- Levin E, Conners C, Sparrow E, Hinton S, Erhardt D, Meek W, Rose J, et al. Nicotine effects on adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychopharmacology. 1996;123(1):55–63. doi: 10.1007/BF02246281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIDDLE PF, LAURENS KR, KIEHL KA, NGAN ETC. Abnormal function of the brain system supporting motivated attention in medicated patients with schizophrenia: an fMRI study. Psychological medicine. 2006;36(8):1097–1108. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706007677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Liang M, Zhou Y, He Y, Hao Y, Song M, Yu C, et al. Disrupted small-world networks in schizophrenia. Brain: a journal of neurology. 2008;131(4):945–961. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynall M, Bassett D, Kerwin R, McKenna P, Kitzbichler M, Muller U, Bullmore E. Functional connectivity and brain networks in schizophrenia. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2010;30(28):9477–87. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0333-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makris N, Seidman LJ, Ahern T, Kennedy DN, Caviness VS, Tsuang MT, Goldstein JM. White matter volume abnormalities and associations with symptomatology in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. 2010;183(1):21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2010.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin LF, Freedman R. International Review of Neurobiology00747742. Vol. 78. Elsevier; 2007. International Review of Neurobiology; pp. 225–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesulam M. From sensation to cognition. Brain: a journal of neurology. 1998;121(Pt6):1013–52. doi: 10.1093/brain/121.6.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesulam M-M, Geula C. Nucleus basalis (Ch4) and cortical cholinergic innervation in the human brain: Observations based on the distribution of acetylcholinesterase and choline acetyltransferase. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1988;275(2):216–240. doi: 10.1002/cne.902750205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micheloyannis S, Pachou E, Stam CJ, Breakspear M, Bitsios P, Vourkas M, Erimaki S, et al. Small-world networks and disturbed functional connectivity in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2006;87(1–3):60–66. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestor PJ, Fryer TD, Smielewski P, Hodges JR. Limbic hypometabolism in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Annals of Neurology. 2003;54(3):343–351. doi: 10.1002/ana. 10669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquale V, Massobrio P, Bologna LL, Chiappalone M, Martinoia S. Self-organization and neuronal avalanches in networks of dissociated cortical neurons. Neuroscience. 2008;153(4):1354–1369. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Percival DB, Walden AT. Wavelet Methods for Time Series Analysis. Cambridge Univ Pr; 2006. p. 594. [Google Scholar]

- Rubinov M, Knock SA, Stam CJ, Micheloyannis S, Harris AWF, Williams LM, Breakspear M. Small-world properties of nonlinear brain activity in schizophrenia. Human Brain Mapping. 2009;30(2):403–416. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM. The future of FMRI connectivity. NeuroImage. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stam CJ, de Haan W, Daffertshofer A, Jones BF, Manshanden I, van Cappellen van Walsum AM, Montez T, et al. Graph theoretical analysis of magnetoencephalographic functional connectivity in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain: a journal of neurology. 2008;132(1):213–224. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stam C, Jones B, Nolte G, Breakspear M, Scheltens P. Small-World Networks and Functional Connectivity in Alzheimer’s Disease. Cerebral Cortex. 2006;17(1):92–99. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Supekar K, Menon V, Rubin D, Musen M, Greicius MD. Network Analysis of Intrinsic Functional Brain Connectivity in Alzheimer’s Disease. In: Sporns O, editor. PLoS Computational Biology. 6. Vol. 4. 2008. p. e1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanabe J, Nyberg E, Martin LF, Martin J, Cordes D, Kronberg E, Tregellas JR. Nicotine effects on default mode network during resting state. Psychopharmacology. 2011;216(2):287–295. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2221-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson P, Hayashi K, de Zubicaray G, Janke A, Rose S, Semple J, Herman D, et al. Dynamics of gray matter loss in Alzheimer’s disease. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2003;23(3):994–1005. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-03-00994.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzourio-Mazoyer N, Landeau B, Papathanassiou D, Crivello F, Etard O, Delcroix N, Mazoyer B, et al. Automated Anatomical Labeling of Activations in SPM Using a Macroscopic Anatomical Parellation of the MNI MRI Single-Subject Brain. NeuroImage. 2002;15(1):273–289. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace TL, Porter RHP. Targeting the nicotinic alpha7 acetylcholine receptor to enhance cognition in disease. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2011;82(8):891–903. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang AY, Lonmann KM, Yang CK, Zimmerman EI, Pantazopoulos H, Herring N, Berretta S, et al. Bipolar disorder type 1 and schizophrenia are accompanied by decreased density of parvalbumin- and somatostatin-positive interneurons in the parahippocampal region. Acta Neuropathologica. 2011;122(5):615–626. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0881-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Su T-P, Zhou Y, Chou K-H, Chen I-Y, Jiang T, Lin C-P. Anatomical insights into disrupted small-world networks in schizophrenia. NeuroImage. 2012;59(2):1085–1093. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts DJ, Strogatz SH. Collective dynamics of “small-world” networks. Nature. 1998;393(6684):440–442. doi: 10.1038/30918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang Z, Huguenard J, Prince D. Cholinergic switching within neocortical inhibitory networks. Science (New York, NY) 1998;281(5379):985–8. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5379.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalesky A, Fornito A, Harding IH, Cocchi L, Yücel M, Pantelis C, Bullmore ET. Whole-brain anatomical networks: does the choice of nodes matter? NeuroImage. 2010;50(3):970–983. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalesky A, Fornito A, Seal ML, Cocchi L, Westin C-F, Bullmore ET, Egan GF, et al. Disrupted Axonal Fiber Connectivity in Schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry. 2011;69(1):80–89. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]