Abstract

Objective

To establish a method to identify patients with primary immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) utilizing administrative data from diverse data sources that would be appropriate for epidemiologic studies of ITP, regardless of patients’ age and source of health care.

Study Design and Setting

Medical records of the Oklahoma University Medical Center, 1995–2004, were reviewed to document the accuracy of the administrative code ICD-9-CM 287.3 for identifying children and adults with ITP, using novel, explicit levels of evidence to identify patients with a definite diagnosis. The proportion of patients diagnosed by hematologists compared to non-hematologists and the proportion of patients diagnosed as outpatients compared to inpatients were determined.

Results

For children, age <16 years, 323 outpatient medical records were reviewed; 225 adult outpatient medical records were reviewed. The positive predictive value for the administrative code for identifying patients with a definite diagnosis of ITP by a hematologist was 0.72 in children and 0.69 in adults. In 98% of children and 92% of adults seen as outpatients, the definite diagnosis of ITP was established by a hematologist. One hundred eighteen child and 141 adult inpatient medical records were reviewed. In 95% of children and 83% of adults, the definite diagnosis of ITP by a hematologist was established as an outpatient.

Conclusion

This study confirmed the previously reported positive predictive value for the administrative code for identifying patients with ITP. Additionally, it was determined that analysis of hematologists’ outpatient administrative codes identified most children and adults with ITP.

Keywords: primary immune thrombocytopenia, ITP, administrative data, validity, ICD-9-CM 287.3

INTRODUCTION

Epidemiologic studies of primary immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) require a method with documented validity for patient identification from administrative data. Documentation of patients with ITP in administrative data may be imprecise because ITP has no explicit defining criteria. The diagnosis of ITP is established only by the presence of isolated thrombocytopenia without another clinically apparent etiology.(1–3) Identification of ITP is made more difficult because it is uncommon, with an annual incidence of only 2–6 cases per 100,000 population per year,(4) and may therefore be unfamiliar to primary care physicians. A previous study by Segal and Powe(5) documented that the sensitivity and specificity of the administrative code for ITP, International Classification of Diseases, 9th version Clinical Modification code (ICD-9-CM) 287.3, were sufficient to identify patients for analysis (5) and they used this administrative code to estimate the prevalence of ITP from Maryland Health Care Commission utilization data.(6) The Maryland Health Care Commission database contains information on health services supported by private insurance companies and health maintenance organizations. Therefore this analysis excluded uninsured patients, patients receiving health care supported by Medicaid, the Veterans Administration, and many patients age ≥65 years supported by Medicare.(6)

The objective of this study was to establish and document the validity of a method to identify patients with ITP utilizing administrative data from diverse data sources that would be appropriate for epidemiologic studies of ITP, regardless of patients’ age and source of health care. This study had three specific aims: [1] determine the accuracy of the administrative code for ITP, ICD-9-CM 287.3, in children and adults, [2] determine if administrative code data limited to hematologists were sufficient to identify most patients with ITP, [3] determine if administrative code data limited to outpatient records were sufficient to identify most patients with ITP.

METHODS

Definitions

Time period

Since ITP is an uncommon disorder,(4) a period of 10 years, 1995–2004, was selected to identify a sufficient number of patients.

Age stratification

We considered individuals <16 years of age to be children. This age cutoff is typical in studies of ITP incidence.(4) Older adolescents more commonly have ITP which is clinically similar to adults.(7)

Data source

We conducted this study at the Oklahoma University Medical Center (OUMC). The study was limited to a single site because obtaining complete primary data from medical records was the principal priority for validation of our methodology. OUMC is the largest single site of hematologists in medical practice in the State of Oklahoma with 22 of the state’s 93 hematologists, including four of the state’s six pediatric hematologists, during this period.(8)

Identification of medical records for patients with ITP

Medical records were identified for all patients billed by the OUMC with an ICD-9-CM code of 287.3 in the first, second, or third position from January 1, 1995 to December 31, 2004. The use of the first three positions was determined a priori to be more inclusive than the previous determination of accuracy of the administrative code 287.3 for identifying patients with ITP (which used the first two positions(5)) and to provide a feasible number of medical records to search for documentation of the diagnosis of ITP. This code remained the same for the entire 10 year period. First and last name, social security number, date of birth, and gender were collected to identify individual patients, to prevent duplicate counting of patients seen at different times in different clinics within the OUMC. Patients were excluded if their residence was outside Oklahoma or if they were incarcerated. ITP was considered to be the diagnosis by any of its common names (primary immune thrombocytopenia, immune thrombocytopenic purpura, autoimmune thrombocytopenic purpura, and idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura) in addition to its standard abbreviation, ITP. Records were also searched to determine the proportion of other rare diseases that are correctly coded by the ICD-9-CM code 287.3 (Evans syndrome, megakaryocytic hypoplasia, congenital thrombocytopenic purpura, hereditary thrombocytopenic purpura, congenital thrombocytopenia, hereditary thrombocytopenia, idiopathic thrombocytopenia, tidal platelet dysgenesis).

Medical record review to determine the diagnosis of ITP

To provide a systematic, reproducible determination of the diagnosis of ITP, a hierarchy of probability was established (Table 1). These definitions were based on a priori assumptions that were revised and then confirmed with the experience of reviewing initial medical records.

Table 1.

Levels of evidence for the diagnosis of ITP established by medical record review

| Evidence level |

Description |

|---|---|

| Definite ITP | 1. A hematologist records the diagnosis of ITP 2. A non-hematologist records the diagnosis of ITP (with no record that a hematologist was consulted) and documents the patient was currently being followed for ITP |

| Probable ITP | 1. A hematologist describes “thrombocytopenia” or “low platelet count” in a child without specifically stating the diagnosis of ITP 2. A non-hematologist records the diagnosis of ITP but does not document the patient was currently being followed for ITP 3. A non-hematologist describes “thrombocytopenia” or “low platelet count” without specifically stating the diagnosis of ITP |

| Unlikely ITP | 1. A hematologist describes “thrombocytopenia” or “low platelet count” in an adult without specifically stating the diagnosis of ITP 2. A non-hematologist records the diagnosis of ITP but within one year a different physician (hematologist or non-hematologist) states that the thrombocytopenia is due to a different etiology (e.g., chemotherapy, HIV infection) |

| Not ITP, correct code | The patient has another disease for which the ICD-9-CM code of 287.3 is correct |

| Not ITP, incorrect code | The hematologist or non-hematologist records the diagnosis of a disease that should not have been coded as 287.3 or states that the thrombocytopenia is due to another condition (e.g., chemotherapy, HIV infection), excluding the diagnosis of ITP |

Determination of ITP as definite

A hematologist’s diagnosis of ITP in the medical record was considered to be a definite level of evidence; there was no attempt to use the medical record to re-assess the accuracy of the hematologist’s diagnosis. If a patient was seen by a hematologist on the first date that an ICD-9-CM code of 287.3 was billed but there was uncertainty regarding the diagnosis in the medical record, the outpatient medical record was reviewed for one year before and after this date, regardless of whether this time included days before 1995 or after 2004, to search for a hematologist’s note documenting the diagnosis of ITP. The two-year period was assumed to be a sufficient interval for a hematologist to establish or exclude the diagnosis of ITP.

A non-hematologist’s diagnosis of ITP was considered definite if there was additional information that the patient was currently being followed for ITP. This distinction reflects the assumptions that hematologists are more familiar with ITP and that they are primarily focused on the problem of ITP. For non-hematologists, such as family medicine physicians and obstetricians, the distinction of ITP from other etiologies of thrombocytopenia may be more difficult and the accuracy of the diagnosis of ITP may be less critical, since it may only be an incidental, additional diagnosis. If a patient was seen by a non-hematologist on the first date the ICD-9-CM code of 287.3 was billed, and he or she recorded the diagnosis of ITP, the patient’s entire medical record from 1995–2004, both inpatient and outpatient, was searched for a hematologist’s consultation note. If a hematologist’s note was found, the final diagnosis was that of the hematologist. If no hematologist’s note was found, the patient was designated according to Table 1.

Determination of ITP as probable or unlikely

If a hematologist’s diagnosis was “thrombocytopenia” or “low platelet count”, without specifically stating the diagnosis of ITP, this was designated as “unlikely ITP” for an adult but “probable ITP” for a child. Since spontaneous remission of ITP is frequent in children,(9) thrombocytopenia may have resolved when a child is seen by a pediatric hematologist and a diagnosis of ITP may not be clear. ITP in adults is typically persistent and will probably be present when patients are seen by a hematologist, who will continue the evaluation to establish a definite diagnosis. If a hematologist did not specifically document the diagnosis of ITP in an adult, it was assumed that the diagnosis of ITP was unlikely.

Calculation of the positive predictive value (PPV

The PPV was defined as the probability that a patient who was billed with the ICD-9-CM code 287.3 had a definite diagnosis of ITP documented in their medical record.

Hematologist-specific PPV

Number of patients with ‘definite ITP’ determined by a hematologist divided by the total number of patients billed with the ICD-9-CM code 287.3 by a hematologist.

Overall PPV

Number of patients with ‘definite ITP’ determined by either a hematologist or non-hematologist, divided by the total number of patients billed with the ICD-9-CM code 287.3.

Proportion of patients with definite ITP determined by a hematologist

To validate whether limiting analysis of administrative records to hematologists would be sufficient to identify most patients with ITP, we calculated the proportion of patients with ‘definite ITP’ (determined by hematologists and non-hematologists) who were determined to have ‘definite ITP’ by hematologists.

Proportion of patients with definite ITP determined by a hematologist as outpatients

To validate whether limiting analysis of administrative records to hematologists’ outpatient records would be sufficient to identify most patients with ITP, separate databases for outpatients and inpatients were established for all patients billed by the OUMC with the ICD-9-CM code of 287.3. Inpatient medical records were only reviewed if the patient was not billed with the ICD-9-CM code of 287.3 as an outpatient. If the inpatient record recorded a definite diagnosis by a hematologist, the entire inpatient medical record was searched for documentation of an outpatient visit to a hematologist. Then we calculated the proportion of patients with “definite ITP” determined by a hematologist as outpatients compared to inpatients.

Ethics approvals

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center.

RESULTS

Children with ITP

Outpatients

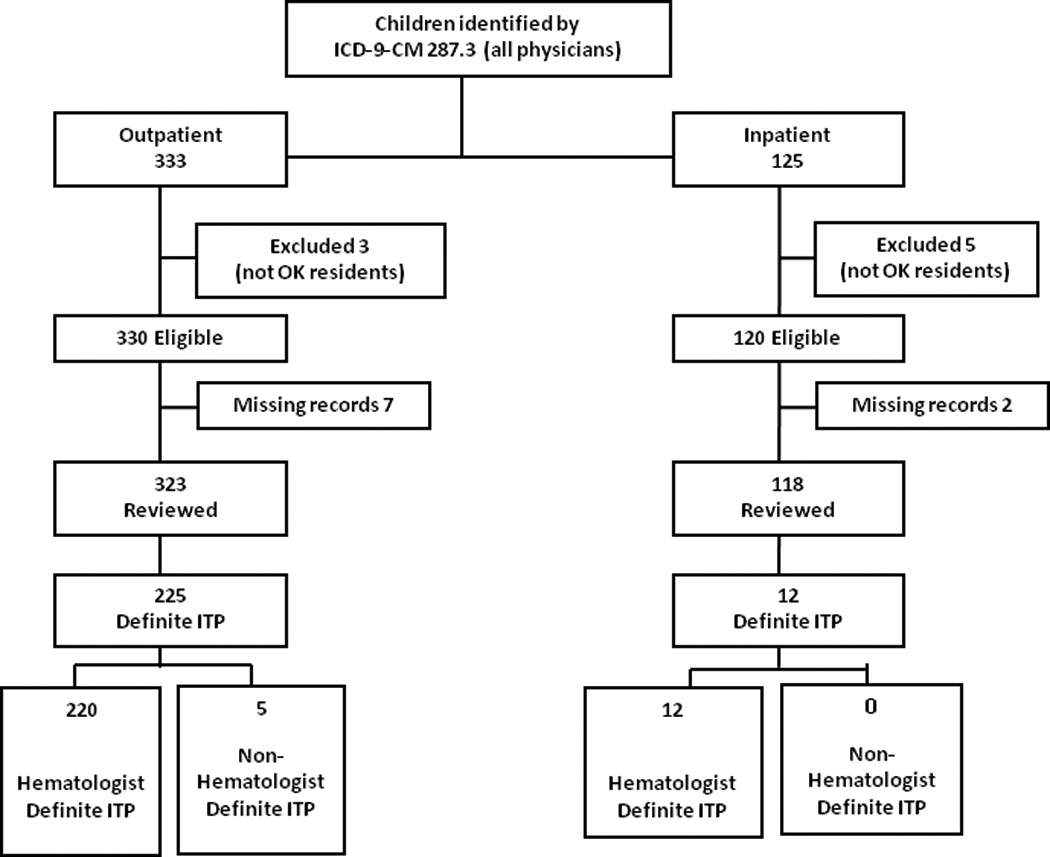

Three hundred thirty-three children who had been billed with the ICD-9-CM code of 287.3, 1995–2004, by all physicians were identified in OUMC outpatient records (Figure 1). Three children were ineligible for this study. Seven medical records were unable to be located or contained no physician notes. Therefore records of 323 (98%) of 330 eligible children were evaluated.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of all children identified by the ICD-9-CMcode 287.3

Final diagnosis determinations

Two hundred-twenty five (70%) of 323 children had a definite diagnosis of ITP (Table 2). Two hundred-twenty children had a definite diagnosis of ITP determined by a hematologist. Five children had a definite diagnosis of ITP recorded only by a non-hematologist. Ten children were determined to have a probable diagnosis of ITP (seven were seen by pediatric hematologists with the final diagnosis ‘thrombocytopenia resolved’; three were seen by non-hematologists who stated thrombocytopenia but did not state a diagnosis of ITP). Eleven children had disorders other than ITP that were correctly coded as ICD-9-CM 287.3 (four had Evan’s syndrome; seven had congenital thrombocytopenia). The remaining 77 children were billed incorrectly; 23 had leukemia; no other diagnosis had more than 6 patients.

Table 2.

Summary by final diagnosis for all persons billed with the ICD-9-CM code of 287.3 as an OUMC outpatient, 1995–2004

| Evidence level children | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Definite (by a hematologist) | 220 | 68.0 |

| Definite (by a non-hematologist) | 5 | 1.5 |

| Probable ITP | 10 | 3.0 |

| Unlikely ITP | 0 | 0.0 |

| Not ITP, correct code, | 11 | 3.5 |

| Not ITP, incorrect code | 77 | 24.0 |

| Total records | 323 | 100.0 |

| Evidence level adults | N | % |

| Definite (by a hematologist) | 120 | 53.3 |

| Definite (by a non-hematologist) | 11 | 5.0 |

| Probable ITP | 10 | 4.4 |

| Unlikely ITP | 4 | 1.8 |

| Not ITP, correct code, | 3 | 1.3 |

| Not ITP, incorrect code | 77 | 34.2 |

| Total records | 225 | 100.0 |

Proportion of children with a definite diagnosis of ITP who were seen by a hematologist

Of the 225 children with a definite diagnosis of ITP seen as an outpatient, the diagnosis was determined by a hematologist in 220 (98%).

Hematologist-specific PPV

Of the 220 children with a definite diagnosis of ITP determined by a hematologist, five were not billed by a hematologist. The total number of children billed by a hematologist with the ICD-9-CM code 287.3 was 300. Therefore the hematologist-specific PPV for outpatients was 0.72 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Positive predictive value (PPV) for the ICD-9-CM code for identifying outpatients diagnosed with ITP by hematologists

| Hematologist-specific PPV | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | Outpatients billed for ICD-9-CM code by hematologists | PPV | |

| All patients | Patients with a definite diagnosis of ITP |

||

| Children | 300 | 215 | 0.72 |

| Adults | 140 | 97 | 0.69 |

| Overall PPV | |||

|

Outpatients billed for ICD-9-CM code by hematologists or non-hematologists |

|||

| Children & Adults | 548 | 356 | 0.65 |

Inpatients

Proportion of children with a definite diagnosis of ITP established as an outpatient rather than as an inpatient

One hundred twenty-five children who had not been billed with the ICD-9-CM code of 287.3 as an outpatient were identified by the ICD-9-CM code of 287.3 in an OUMC inpatient record (Figure 1). Five children were ineligible for this study. Two inpatient medical records were unable to be located or contained no physician notes. Therefore records of 118 (98%) of 120 eligible children were evaluated.

Final diagnosis determinations

Twelve (10%) of the 118 children had a definite diagnosis of ITP. In all 12, the definite diagnosis of ITP was determined by a hematologist (Figure 1).

Of the 232 children (outpatient and inpatient) with a definite diagnosis of ITP determined by a hematologist, 220 (95%) were identified as outpatients by OUMC hematologists. In addition to these 220 children, seven of the 12 children who had a definite diagnosis of ITP as an inpatient had scheduled outpatient appointments with non-OUMC hematologists. Therefore of all 237 children with a definite diagnosis of ITP determined by a hematologist or non-hematologist, or as an outpatient or inpatient, 227 (96%) were seen as an outpatient by a hematologist.

Adults with ITP

Outpatients

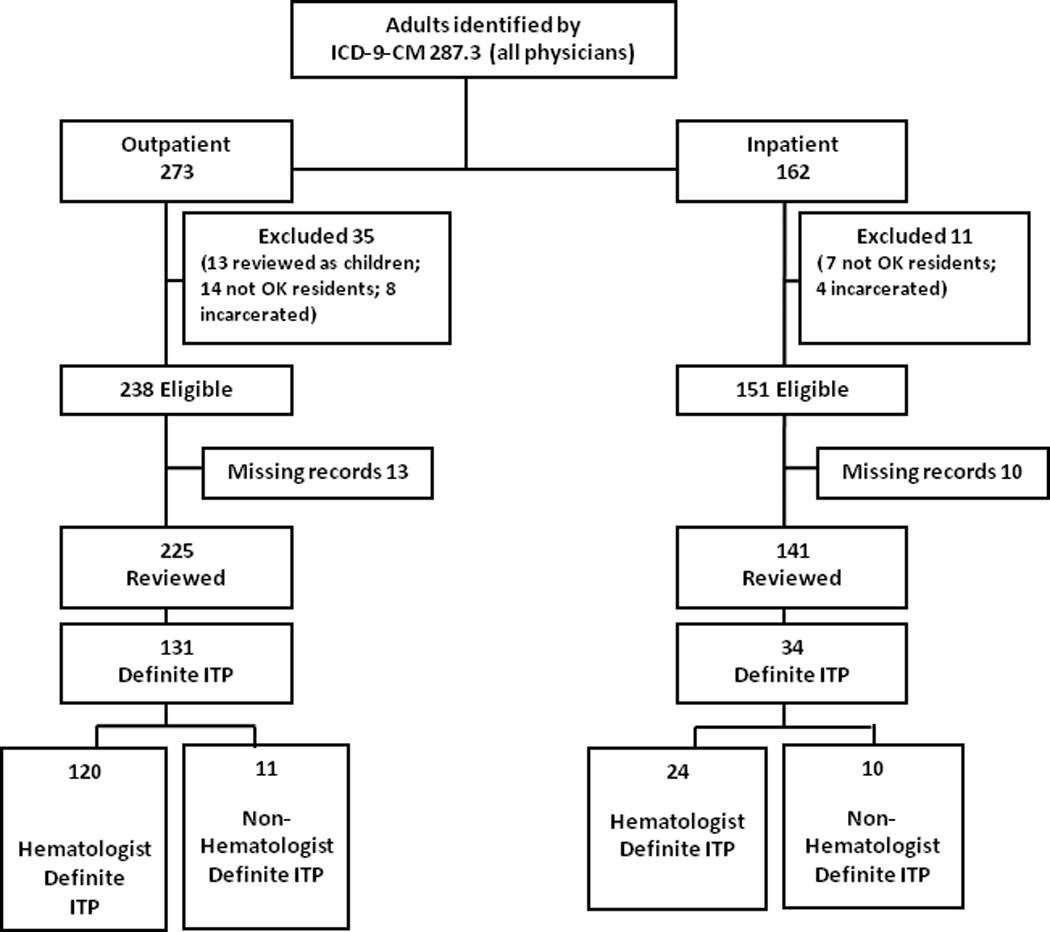

Two hundred seventy-three adults who had been billed with the ICD-9-CM code of 287.3, 1995–2004, by all physicians were identified in OUMC outpatient records (Figure 2). Thirteen adults were excluded because their initial diagnosis of ITP was before their sixteenth birthday and they had been included in the analysis of children. Twenty-two adults were ineligible for this study. Thirteen medical records were unable to be located or contained no physician notes. Therefore records of 225 (95%) of 238 eligible adults were evaluated.

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of all adults identified by the ICD-9-CMcode 287.3

Final diagnosis determinations

One hundred thirty-one (58%) of 225 adults billed with ICD-9-CM of 287.3 had a definite diagnosis of ITP (Table 2). One hundred-twenty adults had a definite diagnosis of ITP determined by a hematologist; 92 (77%) were billed with the code of 287.3 in the first position. Eleven adults had a definite diagnosis of ITP recorded only by a non-hematologist; three (27%) were billed with the code of 287.3 in the first position. Ten adults were determined to have a probable diagnosis of ITP (five were seen by non-hematologists who only described a past history of ITP; five were seen by non-hematologists for other conditions and ‘thrombocytopenia’ was recorded). Four adults seen by hematologists were determined to have an unlikely diagnosis of ITP because thrombocytopenia was described without mentioning ITP. Three adults had disorders other than ITP that were correctly coded with the ICD-9-CM 287.3 (two had Evan’s syndrome; one had congenital thrombocytopenia). The remaining 77 adults were billed incorrectly; 18 had thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura; 9 had gestational thrombocytopenia; 9 had essential thrombocythemia; no other diagnosis had more than 6 patients.

Proportion of adults with a definite diagnosis of ITP who were seen by a hematologist

Of the 131 adults with a definite diagnosis of ITP as an outpatient, the diagnosis was determined by a hematologist in 120 (92%).

Hematologist-specific PPV

Of the 120 adults with a definite diagnosis of ITP determined by a hematologist, only 97 were billed by a hematologist. The total number of adults billed by a hematologist with the ICD-9-CM code 287.3 was 140. Therefore the hematologist-specific PPV for outpatients was 0.69 (Table 3).

Inpatients

Proportion of adults with a definite diagnosis of ITP established as an outpatient rather than as an inpatient

One hundred sixty-two adults who had not been billed with the ICD-9-CM code of 287.3 as an outpatient were identified by the ICD-9-CM code of 287.3 in an OUMC inpatient record (Figure 2). Eleven adults were ineligible for this study. Ten inpatient medical records were unable to be located or contained no physician notes. Therefore records of 141 (93%) of 151 eligible adults were evaluated.

Final diagnosis determinations

Thirty-four (24%) of the 141 adults had a definite diagnosis of ITP; for 24, the definite diagnosis was determined by a hematologist. Ten adults had a definite diagnosis of ITP recorded only by a non-hematologist (Figure 2).

Of the 144 adults (outpatient and inpatient) with a definite diagnosis of ITP determined by a hematologist, 120 (83%) were identified as outpatients by OUMC hematologists. In addition to these 120 adults, 11 of the 34 adults who had a definite diagnosis of ITP as an inpatient had scheduled outpatient appointments with non-OUMC hematologists. Therefore of all 165 adults with a definite diagnosis of ITP determined by a hematologist or non-hematologist, or as an outpatient or inpatient, 131 (79%) were seen as an outpatient by a hematologist.

Children and adults with ITP

Overall PPV for outpatients

A total of 548 children and adults were billed with the ICD-9-CM code of 287.3 by hematologists and non-hematologists as outpatients. Three hundred fifty-six children and adults had a definite diagnosis of ITP determined by either hematologists or non-hematologists. Therefore the overall PPV, regardless of age designation or physician specialty, was 0.65.

DISCUSSION

Our first aim was to determine the accuracy of the administrative code for ITP, ICD-9-CM 287.3, in children and adults. Data from this study confirmed previous results of Segal and Powe(5) who reported a PPV of 0.71 (95% confidence interval 0.63, 0.79) for outpatients of all ages managed by all physicians at Johns Hopkins Hospital. Our overall outpatient PPV of 0.65 was not different. Additionally, our data also demonstrated similar PPVs when data were restricted to hematologists and children were distinguished from adults: 0.72 for children and 0.69 for adults. Therefore when a hematologist billed a child for ITP, the child had a 72% chance of having a definite diagnosis of ITP and an adult had a 69% chance of having a definite diagnosis of ITP. While no specific threshold for PPV is available for this type of study, thresholds specified for measures of reliability, such as a Kappa statistic, would classify the measures of 0.72 and 0.69 as substantial.(10) In reality, thresholds are somewhat specific for the condition under study and for the needs of the study.

Our second aim was to document that hematologists are the principal physicians for patients with ITP and therefore to support the methodology that limiting administrative data to hematologists’ records can identify most patients with ITP. In 98% of children and 92% of adults, the definite diagnosis of ITP was established by a hematologist rather than a non-hematologist. Even including patients with a probable diagnosis of ITP, in 97% of children and 86% of adults the diagnosis was established by a hematologist. These data document that limiting the analysis of administrative data to hematologists’ records can identify most patients with ITP and are consistent with our previous survey of physician referral patterns for patients with thrombocytopenia. This survey of primary care providers in the Oklahoma Practice-based Research Network documented that 75% of respondents were ‘likely’ to send a patient with moderate thrombocytopenia (platelet count 30,000/µL) to a hematologist for further evaluation and management.(11) The likelihood of referral increased to 85% when the moderate thrombocytopenia was associated with mild bleeding symptoms (petechiae) and to 92% when the patient presented with severe thrombocytopenia (platelet count 10,000/µL).(11)

Our third aim was to document that most patients with ITP have at least part of their care as outpatients. Five percent of children and 17% of adults with a definite diagnosis of ITP by a hematologist were only identified by inpatient medical records. However, 7 of the 12 children and 11 of the 34 adults only identified by inpatient medical records had scheduled outpatient follow-up appointments with hematologists. Therefore we determined that limiting medical review to outpatient records would identify 98% of children and 91% of adults with a definite diagnosis of ITP by a hematologist.

Combining the results comparing hematologists to non-hematologists and outpatient records to inpatient records, these data document that 96% of all children and 79% of all adults who have a definite diagnosis of ITP can be identified from the outpatient records of hematologists.

Our data together with previous data(5) demonstrated that that misclassification was rarely due to diseases other than ITP that were also correctly coded by ICD-9-CM 287.3. Almost all misclassification was due to diseases being incorrectly coded. Seventy-seven children were coded incorrectly as 287.3; many had leukemia. Seventy-seven adults were coded incorrectly; many had thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, gestational thrombocytopenia, or essential thrombocythemia. Therefore, even with the refinement of the ICD-9-CM 287.3 code which now has specific codes for each disease other than ITP within that code (October 1, 2005), the frequency of coding inaccuracies may not change.

An important element of this study was to establish levels of evidence for the diagnosis of ITP established by medical record review to identify patients with a definite diagnosis of ITP. To develop these levels of evidence required extensive review of medical records and interpretation of notes written by multiple physicians of different medical specialties. As our experience with medical record review encountered many complex situations, our system evolved to the final levels of evidence reported here. Although some patients designated as “probable” ITP may have had ITP, the number of patients in this category was small, 3% of children and 4% of adults.

A limitation of this study is that it only analyzed patients at the OUMC and the results may not be generalizable to community hematologists throughout Oklahoma or other states or to other administrative databases. The OUMC has all medical specialties within a single medical center, and OUMC patients may be seen by medical specialists more frequently than patients receiving community care. More patients at OUMC may be uninsured and may be more seriously ill than patients cared for by community physicians; this may also result in care by a greater variety of medical specialists. The greater number of physicians of different medical specialties may decrease the role of hematologists. On the other hand, referral among physicians may be greater within the OUMC resulting in a greater fraction of patients with ITP managed by hematologists. With other administrative databases, it may not be feasible to identify data restricted to hematologists. However, the PPV in our study was similar when all patients with a definite diagnosis of ITP were analyzed compared to patients diagnosed by hematologists. However, as expected, ITP was more likely to be the principal diagnosis for hematologists, coded in the first position, than for non-hematologists.

A strength of this methodology is that it may be a model for epidemiologic studies of other uncommon disorders which do not have explicit diagnostic criteria and are primarily managed by specialists as outpatients. Additional strengths of this study are the consistency with the previous data(5) and the completeness of the medical record review. For children and adults, respectively, 98% and 95% of eligible medical records across 10 years were reviewed.

In conclusion, these data document the validity of a method for identifying patients with ITP from diverse data sources utilizing administrative records, regardless of patients’ age and source of healthcare. Confirmation of the accuracy of the ICD-9-CM code for identifying patients with ITP is important to establish the validity of epidemiologic studies using administrative databases. Limiting analysis of administrative data to hematologists’ outpatient records provided a feasible method to identify most children and adults with ITP.

Acknowledgments

This project supported in part by the Utay Family Blood Research Fund. Dr. Terrell is partially supported by NIH 1U01HL72283-09S1.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest with the data or subject of this manuscript.

Reference List

- 1.Rodeghiero F, Stasi R, Gernsheimer T, Michel M, Provan D, Arnold DM, et al. Standardization of terminology, definitions, and outcome criteria in immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) in adults and children. Report from an international working group. Blood. 2009;113:2386–2393. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-162503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Provan D, Stasi R, Newland AC, Blanchette VS, Bolton-Maggs PHB, Bussel JB, et al. International consensus report on the investigation and management of primary immune thrombocytopenia. Blood. 2010;115:168–186. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-06-225565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neunert CE, Lim W, Crowther MA, Cohen AR, Solberg LA, Jr, Crowther M. The American Society of Hematology 2011 evidenced-based practice guideline for immune thrombocytopenia. Blood. 2011;117:4190–4207. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-302984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Terrell DR, Beebe LA, Vesely SK, Neas BR, Segal JB, George JN. The incidence of immune thrombocytopenic purpura in children and adults: a critical review of published reports. Amer J Hematol. 2010;85:174–180. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Segal JB, Powe NR. Accuracy of indentification of patients with immune thrombocytopenic purpura through administrative records: a data validation study. Amer J Hematol. 2004;75:12–17. doi: 10.1002/ajh.10445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Segal JB, Powe NR. Prevalence of immune thrombocytopenia: analysis of administrative data. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:2377–2383. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.02147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bolton-Maggs PH. Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Arch Dis Child. 2000;83:220–222. doi: 10.1136/adc.83.3.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Terrell DR, Beebe LA, Vesely SK, Neas BR, Segal JB, George JN. Prevalence of primary immune thrombocytopenia in Oklahoma. Submitted for publication. 2012 doi: 10.1002/ajh.23262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Imbach P, Kuhne T, Muller D, Berchtold W, Zimmerman S, Elalfy M, et al. Childhood ITP: 12 months follow-up data from the prospective registry I of the intercontinental childhood ITP study group (ICIS) Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005:1–6. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Terrell DR, Beebe LA, George JN, Vesely SK, Mold JW. Referral of patients with thrombocytopenia from primary care clinicians to hematologists. Blood. 2009;113:4126–4127. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-01-200907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]