Abstract

Diabetes insipidus (DI) is characterized by excessive urination and thirst. This disease results from inadequate output of antidiuretic hormone (ADH) from the pituitary gland or the absence of the normal response to ADH in the kidney. We present a case of transient central DI in a patient who underwent a cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) for coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). A 44-yr-old male underwent a CABG operation. An hour after the operation, the patient developed polyuria and was diagnosed with central DI. The patient responded to desmopressin and completely recovered five days after surgery. It is probable that transient cerebral ischemia resulted in the dysfunction of osmotic receptors in the hypothalamus or hypothalamus-pituitary axis during CPB. It is also possible that cardiac standstill altered the left atrial non-osmotic receptor function and suppressed ADH release. Therefore, we suggest that central DI is a possible cause of polyuria after CPB.

Keywords: Polyuria, Central Diabetes Insipidus, Aorto-Coronary Bypass

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes insipidus (DI) is characterized by copious excretion of urine and excessive thirst. This disease is caused by insufficient production and secretion of antidiuretic hormone (ADH), or the inability of the kidney tubules to respond to ADH. The former condition is referred to as central DI and the latter as nephrogenic DI. Possible causes of central DI include head trauma, pituitary surgery, neoplasms, infection, inflammation, vascular disease, and genetic defects. However, 30% to 50% of central DI cases are considered idiopathic (1). Development of this disease after open-heart surgery has been rarely reported in the literatures (2, 3). To the best of our knowledge, the patient presented in this paper represents the first reported case of central DI associated with open-heart surgery in the Republic of Korea. In individuals undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB), several endocrine changes due to surgical stress can occur (4, 5). There are some conflicting reports regarding the levels of ADH after open-heart surgery. ADH levels were found to increase in some studies (6, 7) whereas ADH deficiency developed in other cases (2, 3). In the present report, we describe a case of transient central DI that developed after CPB for coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). We also discuss the etiology, pathogenesis, and differential diagnosis of this disease based on a literature review.

CASE DESCRIPTION

On November 17, 2011, A 44-yr-old male underwent CPB to treat a 2 vessel disease involving occlusions in the left anterior descending and right coronary arteries. He was previously diagnosed with hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus. There was no prior history of polydipsia, polyuria, or head injury. In addition, the patient did not have a familial history of polyuria. On the day of admission, his blood pressure was 127/66 mmHg and heart rate was 79 beats per minute. The CABG operation lasted 6 hr with a CPB time of 115 min and aortic cross clamp time of 69 min. The myocardium was protected by cold cardioplegia. There were no intra-operative hypotensive episodes or other major complications. Intra-operative mean blood pressure was maintained between 75 mmHg to 90 mmHg.

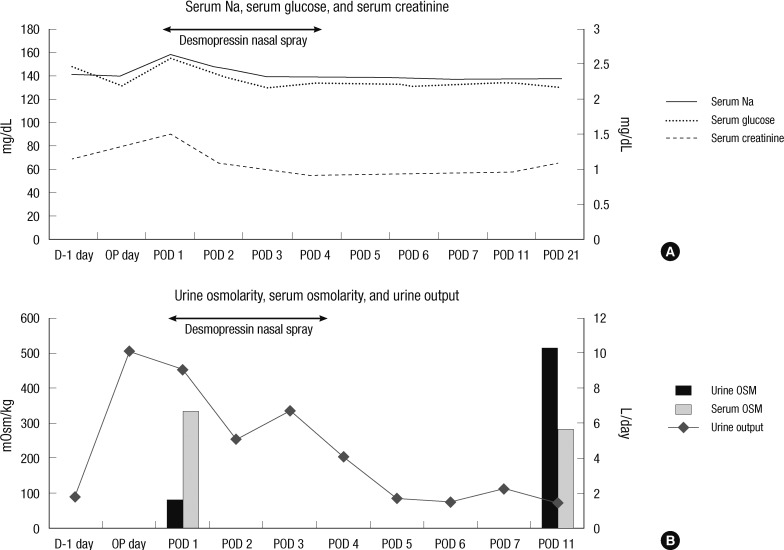

One hour after the operation, the patient's urinary output increased to about 1,000 mL/hr. His mental status was normal and there were no clinical signs of neurologic deficit. Serum creatinine levels increased slightly from 1.15 mg/dL to 1.3 mg/dL. Serum glucose and sodium concentrations were 137 mg/dL and 140 mEq/L (Fig. 1A). Specific gravity of the urine was 1.020. The urine was also negative for protein, glucose, and occult blood. Other laboratory findings did not reveal any meaningful changes compared to the patient's pre-operative data. Over-hydration with hypertonic solutions nor large amounts of diuretics were not administered during the operation.

Fig. 1.

Changes in the patient's clinical course and laboratory data.

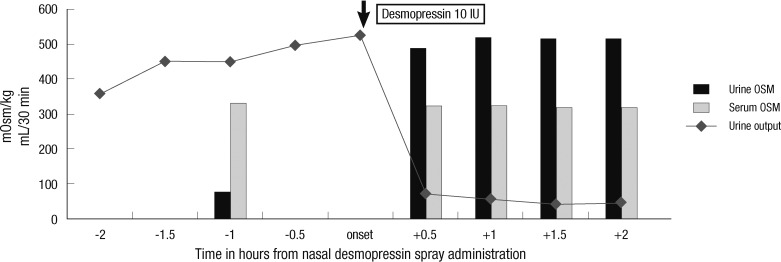

On the first post-operative day, the patient's urinary output was continued up to 1,050 mL/hr and he was referred to the nephrology clinic. His clinical and laboratory findings revealed a serum osmolality of 333 mOsm/kg, urine osmolality of 80 mOsm/kg, and serum sodium of 155 mEq/L (Fig. 1B). Considering the patient's serum sodium level and osmolality, 10 mcg of a desmopressin nasal spray was administered for a desmopressin stimulation test (Fig. 2) without water deprivation. His urine output declined dramatically to 125 mL/hr 30 min after desmopressin use. At 60 min after nasal desmopressin administration, urine osmolality increased to 518 mOsm/kg and urine output declined from 1,050 mL/hr to 80 mL/hr. Based on the laboratory data and an increase in urine osmolality of more than 100% measured by the desmopression stimulation test, the patient was diagnosed with complete central DI.

Fig. 2.

Desmopressin stimulation test performed on the first post-operative day.

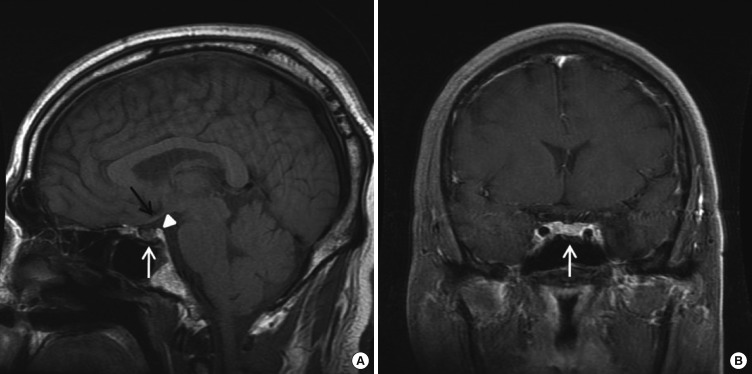

On the third post-operative day, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed to exclude brain injury that may have occurred during operation. However, there were no abnormal findings (Fig. 3). Urine output was stabilized by intermittent nasal desmopressin administration until the fourth post-operative day at amount of 150-200 mL/hr. Thereafter, no further therapy was necessary and the patient has remained symptom-free with no complaints of altered urinary output or excessive thirst.

Fig. 3.

T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at the level of the hypothalamus-pituitary axis. Sagittal (A) and coronal (B) T1-weighted scans show a normal pituitary stalk (black arrow), pituitary gland (white arrow). There was a normal bright spot (arrow head) in the posterior pituitary gland of hyperintense signal in T1-weighted sagittal image (A).

DISCUSSION

We have presented a rare case of transient central DI which developed after CABG. CPB can induce some physiologic changes including fluid, electrolyte, and acid-base imbalances; renal complications, embolic events, and neuro-endocrine changes. Despite some conflicting reports (2, 3, 6-8) showing variations in ADH levels during and after CPB, DI has been rarely encountered in post-bypass patients. ADH is an octapeptide produced in the superoptic and paraventricular nuclei of the hypothalamus, transported along the hypothalamus-pituitary axis, and stored in the pituitary gland. This factor is normally released from the pituitary gland after non-osmotic or osmotic stimulus. Non-osmotic stimulus is associated with variation in extracellular fluid (ECF) volume. When ECF levels are decreased, there is a concomitant increase of ADH release. This is mediated through volume receptors located in the left atrium of the heart, aortic arch, and carotid artery. Osmotic stimulus that causes the release of ADH involves an increase of plasma osmolality mediated through osmoreceptors in the hypothalamus. After ADH is released from the posterior pituitary axis in the presence of either osmotic or non-osmotic stimulus, it directly acts on the kidney (9). Based on our understanding of ADH production, stimulation, release, and action, we focused on disturbances of the osmotic or non-osmotic pathway and the hypothalamus-pituitary axis as the causes of central DI.

We first considered the possibility of osmoregulation or hypothalamus-pituitary axis disturbances as a mechanism of central DI. The anterior hypothalamus cells play a role in osmoregulation. Increases in ECF osmolality due to dehydration decrease the volume of osmoreceptor cell, which triggers an electric stimulus leading to membrane depolarization, exocytosis, and the release of ADH by hypothalamus-pituitary axis. The osmotic stimulus which triggers ADH release is initiated by 1 to 2% changes in ECF (10). In our patient, serum osmolality was increased to 333 mOsm/kg and sustained in high level, and massive polyuria continued. There were no specific abnormalities suspecting the disturbance of osmotic stimulus or hypothalamus-pituitary axis. In addition, there was no abnormal finding on brain MRI. And then, we considered the possibility of vascular disturbances associated with cerebral ischemia. Sheehan and Murdock described postpartum pituitary necrosis in patients who were in hemorrhage shock after parturition (11). They postulated that a circulatory collapse due to diminished blood flow would result in vascular thrombosis in the pituitary gland. They later extended this theory to include posterior necrosis as a cause of DI (12). In the present study, we could not overlook the possibility of transient cerebral ischemia resulting in disturbances of the osmotic stimulus receptor or hypothalamus-pituitary axis although no severe posterior pituitary damage occurred. According to some reports (13-15), the incidence of cerebral ischemia developing after open-heart surgery is generally between 1% and 6%. Most cases of stroke or transient ischemic damage following open-heart surgery occur in patients in whom no carotid stenosis or other clear etiologic factors can be uncovered. However, 6% to 12% of CABG patients have carotid stenosis greater than 50% preoperatively but have no bruit on physical examination (16). Since we did not perform a carotid doppler study, subclinical carotid stenosis could not be excluded. In addition, CPB itself could cause transient subclinical circulatory problems in the cerebral blood supply.

Next, we considered the possibility of non-osmotic stimulus disturbances. The major non-osmotic stimulus appears to be associated with volume receptors in the left atrium, which communicate with the hypothalamus through the vagus parasympathetic stimulus. A decrease in the left atrial volume is associated with diminished parasympathetic afferent drive and a release in ADH, whereas an increase in volume at the receptor is associated with increased parasympathetic afferent drive and suppression of ADH release (9). We assumed that the left atrial non-osmotic receptor function could be transiently altered by a standstill heart during CPB. And this would result in an increase in parasympathetic afferent drive associated with suppression of ADH release.

Given the above postulations, concomitant disturbances by both stimuli could induce central DI development. During our diagnosis, we considered the other possible causes of polyuria for exclusion: iatrogenic fluid overloading, osmotic diuresis, and recovery from acute tubular necrosis. These conditions were excluded based on the patient's clinical course and laboratory data.

DI development after extracorporeal circulation has been rarely reported and is an overlooked postoperative complication. However, DI should be considered in individuals who have undergone open-heart surgery and develop polyuria. It was reported that the presence of carotid bruit, history of cerebral ischemic disease, atrial fibrillation, bypass times greater than 2 hr, previous myocardial infarction, left ventricular mural thrombus, air in the bypass system, and micro-aggregate formation increase the risk of transient ischemic attack or stroke following open-heart surgery (17-20). With these risk factors, an operator must be aware of post-operative cerebral ischemic complications given the possibility of central DI development with polyuria. When DI is diagnosed, prompt and adequate ADH administration may prevent further serious problems. In conclusion, we suggest that central DI is a possible cause of polyuria after CPB.

Footnotes

This study was supported by grants (A111345, A102065) from the Korea Healthcare Technology R & D Project, Ministry for Health, Welfare and Family Affair, Republic of Korea.

References

- 1.Blotner H. Primary or idiopathic diabetes insipidus: a system disease. Metabolism. 1958;7:191–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuan P, Messenger JC, Ellestad MH. Transient central diabetes insipidus after aortocoronary bypass operations. Am J Cardiol. 1983;52:1181–1183. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(83)90570-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ashraf O, Sharif H, Shah M. A case of transient diabetes insipidus following cardiopulmonary bypass. J Pak Med Assoc. 2005;55:565–566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taylor KM, Wright GS, Reid JM, Bain WH, Caves PK, Walker MS, Grant JK. Comparative studies of pulsatile and nonpulsatile flow during cardiopulmonary bypass. II. The effects on adrenal secretion of cortisol. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1978;75:574–578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.El-Etr AA, Glisson SN. Endocrine changes during anesthesia and cardiopulmonary bypass. Cleve Clin Q. 1981;48:132–138. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.48.1.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Philbin DM, Coggins CH, Wilson N, Sokoloski J. Antidiuretic hormone levels during cardiopulmonary bypass. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1977;73:145–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stanley TH, Philbin DM, Coggins CH. Fentanyl-oxygen anesthesia for coronary artery surgery, cardiovascular and antidiuretic hormone response. Can Anaesth Soc J. 1979;26:168–172. doi: 10.1007/BF03006976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robinson RO, Pagliero KM. Polyruia after cardiac surgery. Br Med J. 1970;3:265. doi: 10.1136/bmj.3.5717.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schrier RW, Berl T, Anderson RJ. Osmotic and nonosmotic control of vasopressin release. Am J Physiol. 1979;236:F321–F332. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1979.236.4.F321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schrler RW, Leaf A. Effect of hormones on water, sodium, chloride, and potassium metabolism. In: Williams RH, editor. Textbook of endocrinology. 6th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1981. pp. 1032–1037. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sheehan HL, Whitehead R. The neurohypophysis in post-partum hypopituitarism. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1963;85:145–169. doi: 10.1002/path.1700850115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sheehan HL, Murdock R. Postpartum necrosis of the anterior pituitary; pathological and clinical aspects. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Commonw. 1938;45:456–487. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Breuer AC, Furlan AJ, Hanson MR, Lederman RJ, Loop FD, Cosgrove DM, Greenstreet RL, Estafanous FG. Central nervous system complications of coronary artery bypass graft surgery: prospective analysis of 421 patients. Stroke. 1983;14:682–687. doi: 10.1161/01.str.14.5.682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Turnipseed WD, Berkoff HA, Belzer FO. Postoperative stroke in cardiac and peripheral vascular disease. Ann Surg. 1980;192:365–368. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198009000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ropper AH, Wechsler LR, Wilson LS. Carotid bruit and the risk of stroke in elective surgery. N Engl J Med. 1982;307:1388–1390. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198211253072207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hart RG, Easton JD. Management of cervical bruits and carotid stenosis in preoperative patients. Stroke. 1983;14:290–297. doi: 10.1161/01.str.14.2.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reed GL, Singer DE, Pilard EH. Stroke following coronary artery bypass surgery. A case control estimate of the risk of carotid bruits. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:1246–1250. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198811103191903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heikkinen L. Clinically significant neurological disorders following open heart surgery. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1985;33:201–206. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1014119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Breuer AC, Franco I, Marzewski D, Soto-Velasco J. Left ventricular thrombi seen by ventriculography are a significant risk factor for stroke in open heart surgery. Ann Neurol. 1981;10:103–104. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taylor GJ, Malik SA, Colliver JA, Dove JT, Moses HW, Mikell FL, Batchelder JE, Schneider JA, Wellons HA. Usefulness of atrial fibrillation as a predictor of stroke after isolated coronary artery bypass grafting. Am J Cardiol. 1987;60:905–907. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(87)91045-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]