Abstract

Anatomical studies in the macaque cortex and functional imaging studies in humans have demonstrated the existence of different cortical areas within the IntraParietal Sulcus (IPS). Such functional segregation, however, does not correlate with presently available architectonic maps of the human brain. This is particularly true for the classical Brodmann map, which is still widely used as an anatomical reference in functional imaging studies. The aim of this cytoarchitectonic mapping study was to use previously defined algorithms to determine whether consistent regions and borders can be found within the cortex of the anterior IPS in a population of ten postmortem human brains. Two areas, the human IntraParietal area 1 (hIP1) and the human IntraParietal area 2 (hIP2), were delineated in serial histological sections of the anterior, lateral bank of the human IPS. The region hIP1 is located posterior and medial to hIP2, and the former is always within the depths of the IPS. The latter, on the other hand, sometimes reaches the free surface of the superior parietal lobule. The delineations were registered to standard reference space, and probabilistic maps were calculated, thereby quantifying the intersubject variability in location and extent of both areas. In the future, they can be a tool in analyzing structure – function relationships and a basis for determining degrees of homology in the IPS among anthropoid primates. We conclude that the human intraparietal sulcus has a finer grained parcellation than shown in Brodmann’s map.

Keywords: stereotaxic maps, cytoarchitecture, parietal cortex, human intraparietal sulcus, mapping

Introduction

Although many neuroimaging studies have recently focused attention on the IntraParietal Sulcus (IPS), little is known about the basic cellular architecture of its cortex. This study was designed to determine whether the anterior ventral bank of the human IPS can be divided into consistently defined cortical regions and to map the topographic relationships of any such regions with each other, with an internationally recognized stereotaxic reference space, and with the IPS. With this knowledge, researchers will be better able to interpret both neuroimaging findings of the parietal cortex and data from nonhuman primates.

Neuroimaging studies have observed that cortex in and around regions associated with the IPS becomes active with numerical processing (Pinel et al., 1999, 2001; Eger et al., 2002; Dehaene et al., 2003), and with visuo-spatial and visuo-motor operations (Johnson et al., 1996; Coull and Frith, 1998; Faillenot et al., 1999; Harris et al., 2000; de Jong et al., 2001; Cohen and Andersen, 2002; Eskandar and Assad, 2002).

Better insight into the neuroimaging data can be gained by associating results from functional segregation with defined cytoarchitectonic regions. Until now, however, anatomical maps of the human IPS region have been qualitative and did not reliably subdivide the cortex of the IPS. In these earlier maps, the IPS was used more as a landmark to separate the superior from the inferior parietal lobule than as a region containing cortical areas. This is true in particular for the Brodmann map (1909), which is still widely used as the anatomical reference for functional imaging studies.

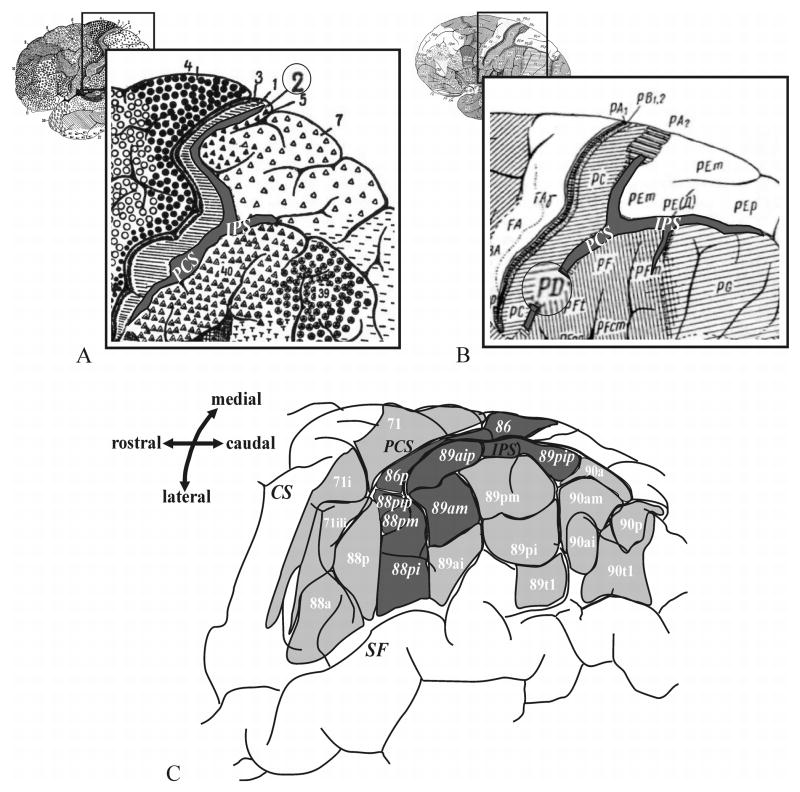

Brodmann (Fig. 1A) divided the posterior parietal cortex into two regions; a dorsal region containing areas 5 and 7 (upper parietal lobule), and a ventral region containing areas 39 and 40 (lower parietal lobule). In his map, the border between the dorsal and the ventral areas is approximately marked by the IPS, although the details of divisions in the depth of the sulcus were not provided (Brodmann, 1909). von Economo and Koskinas (1925; Fig. 1B) also distinguished the superior (PE) from the inferior (PF, PG) parietal lobule. In addition, they described an area, PD, in the region of the inferior postcentral sulcus, and added a subparcellation to this area, PDE, in the anterior IPS. The cytoarchitecture of the posterior IPS was characterized as subtype PED by von Economo and Koskinas. Gerhardt (1940; Fig. 1C) made a very detailed cytoarchitectonic division of the parietal lobe and the IPS based on a single hemisphere. She delineated 9 areas within the IPS and 6 on the lower bank of the IPS; this detailed parcellation has never been replicated, nor has it played any role in interpreting functional imaging studies. For an overview of the different parietal cortical maps see Zilles and Palomero-Gallagher (2001) and Zilles (2004).

Figure 1.

Classical cytoarchitectonic brain maps of the human brain adapted from (A) Brodmann (1909), (B) von Economo and Koskinas (1925) and (C) Gerhardt (1940). The areas of the anterior intraparietal sulcus are shaded grey. IPS – intraparietal sulcus, CS - central sulcus, SF- Sylvian fissure.

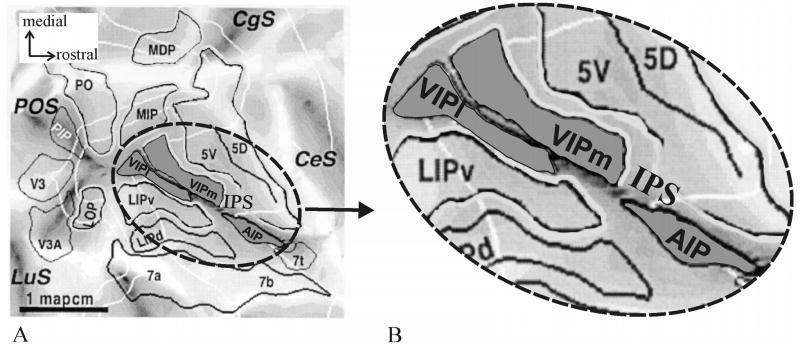

Valuable insights into human neuroimaging studies come from work on experimental animals, especially anthropoid primates. Neurophysiological and architectonic studies of the macaque parietal cortex reveal a highly complex region. Several distinct areas in the depths of the IPS (Fig. 2) have been identified as subdivisions of parietal cortex. Examples include the “Anterior IntraParietal area” (AIP; Taira et al., 1990; Gallese et al., 1994; Sakata et al., 1995, 1998; Murata et al., 1996, 2000), the “Ventral IntraParietal area” (VIP; Maunsell and Van Essen, 1983; Ungerleider and Desimone, 1986; Cavada and Goldman-Rakic, 1989; Colby et al., 1993, 1999), the “Medial IntraParietal area” (MIP; Cohen and Andersen, 2002; Eskandar and Assad, 1999, 2002), the “Lateral IntraParietal area” (LIP; Gnadt and Andersen, 1988; Barash et al., 1991a, b; Andersen et al., 1992) and the “Posterior IntraParietal area” (PIP; Shikata et al., 1996; Sakata et al., 1998; Taira et al., 2000).

Figure 2.

Flat-map of a macaque brain adapted from Lewis and Van Essen (2000a). (A) The map demonstrates anatomic relations of areas in the parietal lobe of an individual macaque brain. (B) shows the anterior IPS at a higher magnification. Note the location of areas AIP and VIP in the ventral anterior IPS. VIP has been subdivided into a medial (VIPm) and a lateral part (VIPl). AIP lies posteriorly from area 7t and laterally from 5V(ventral). Area VIP is located posteriorly from AIP. Its medial neighbor is 5V followed by area MIP (Medial IntraParietal area) more caudally. CeS – central sulcus, CgS – cingulate sulcus, POS – parieto-occipital sulcus, LuS – lunate sulcus, MIP – medial intraparietal area, LIPv/d – ventral/dorsal part of the lateral intraparietal area, PIP – posterior intraparietal area.

Regions around the macaque IPS cortex are, like that of the human, also selectively activated by visuo-spatial and visuo-motor operations, suggesting that human and macaque IPS cortex share equivalent functions (Bremmer et al., 2001; Grefkes et al., 2002). While it is not unreasonable to think that cortical regions of anthropoid primates have many homologous features, the response of humans to numerical processing (Pinel et al., 1999), a highly developed attribute in humans, suggests differences exist. Different cortical architectures separate human from non-human primates (Haug, 1987) in part of the temporal lobe (Buxhoeveden et al., 1996), and the frontal lobe (Petrides and Pandya, 1994; Semendeferi et al., 2001; Sherwood et al., 2004; Petrides et al., 2005), and a specific human cortical architecture or patterns of connections may characterize all or part of this region. Hypotheses to test degrees of homology and homoplasy require morphometric analyses of many features, and the grey level index (GLI) is one proven way to approach this problem (Armstrong et al., 1986; Zilles et al., 1986).

The GLI allows investigators to define cytoarchitectonic borders using algorithms to detect areal borders (Schleicher et al., 1999). The data can then be used to create stereotaxic, cytoarchitectonic probabilistic maps, which in turn provide tools for future comparisons with data from functional imaging studies, e.g., fMRI and PET. In order to avoid any unproven conclusions about the functional significance or putative homologies to areas of the macaque cortex, we used a neutral nomenclature for identified areas. The delineated areas were named human IntraParietal areas (hIP) 1 and 2. They were numbered in the order of their medial to lateral appearance.

A final goal of the study was to analyze the topographic relationships of the areas with respect to the IPS and the PostCentral Sulcus (PCS). Both sulci show highly variable courses, shapes, connections and number of segments (Cunningham, 1882; Retzius, 1896; Connolly, 1950; Ono et al., 1990; Ebeling and Steinmetz, 1995).

Materials and Methods

Histological processing and 3D reconstruction of postmortem brains

Ten postmortem brains (5 males, 5 females; age range: 37 – 86 yrs.; Table 1) were analyzed. The brains were obtained from the body donor program at the University of Düsseldorf in accordance with the local ethical committee. None of the subjects showed any neurological or psychiatric disorders in their clinical records. Handedness of subjects was unknown.

Table 1.

Postmortem brains used in the present study

| Brain-No. | Age (years) | Sex | Cause of death | Fixation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 43 | f | Cor pulmonale | Formalin |

| 2 | 37 | m | Acute right heart failure | Formalin |

| 3 | 54 | m | Myocardial infarction | Formalin |

| 4 | 56 | m | Rectal carcinoma | Formalin |

| 5 | 75 | m | Toxic glomerulonephritis | Formalin |

| 6 | 39 | m | Drowning | Formalin |

| 7 | 85 | f | Mesenteric artery infarction | Bodian |

| 8 | 59 | f | Cardiorespiratory insufficiency | Formalin |

| 9 | 79 | f | Cardiorespiratory insufficiency | Bodian |

| 10 | 86 | f | Cardiorespiratory insufficiency | Formalin |

f, female; m, male

Brains were fixed for several months in 4% formaldehyde or Bodian-fixative, a mixture of formalin, glacial acid and ethanol.

After fixation, meninges were removed and MR imaging was performed, using a Siemens 1.5-T vision MR-scanner (Erlangen, Germany) and a T1-weighted 3D FLASH sequence covering the entire brain (flip angle 40E, repetition time TR = 40 ms, echo time TE = 5 ms). The MR data set of each brain consisted of 128 sagittal sections with a spatial resolution of 1 x 1 x 1.17 mm each and a depth of 8 bits.

Brains were embedded in paraffin and serially sectioned in the coronal plane (20 μm). Each 15th section was mounted on glass slides and silver stained for perikarya (Merker, 1983). During sectioning, each 60th section of the entire series (distance between sections: 1.2 mm) was then digitized with a CCD camera (= histological data set).

The blockface data and the MR sequences of the brains, which had been obtained prior to embedding and sectioning, were used to make 3D reconstructions of the histological sections. Details of the histological processing and 3D-reconstruction have been previously described (Amunts et al., 1999).

Finally, data sets of the postmortem brains were registered to the spatially normalized, T1-weighted MR single-subject brain of the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI; Evans et al., 1993; Collins et al., 1994; Holmes et al., 1998) using an affine, linear transformation and an elastic, non-linear algorithm (Mohlberg et al., 2003; Amunts et al., 2004). The AC-PC line at the level of the inter-hemispherical fissure was matched with the origin (0/0/0) according to the convention of Talairach & Tournoux (1988; = anatomical MNI space) by using a simple translation to shift the data.

Observer-independent definition of areal borders

Cytoarchitectonic analysis was performed in serial coronal sections. Rectangular regions of interest (ROI), covering the full medial-to-lateral extent of the sulcus, were interactively defined at the anterior beginning of the IPS. In each postmortem brain, 15–20 coronal histological sections were investigated. The size of a ROI was approximately 4 – 5 cm2, depending on the cortical thickness and the sulcal course of the IPS.

An image analyzer (KS400; Zeiss) connected to a microscope, with a motorized stage for automatic scanning and focusing, digitized the ROIs.

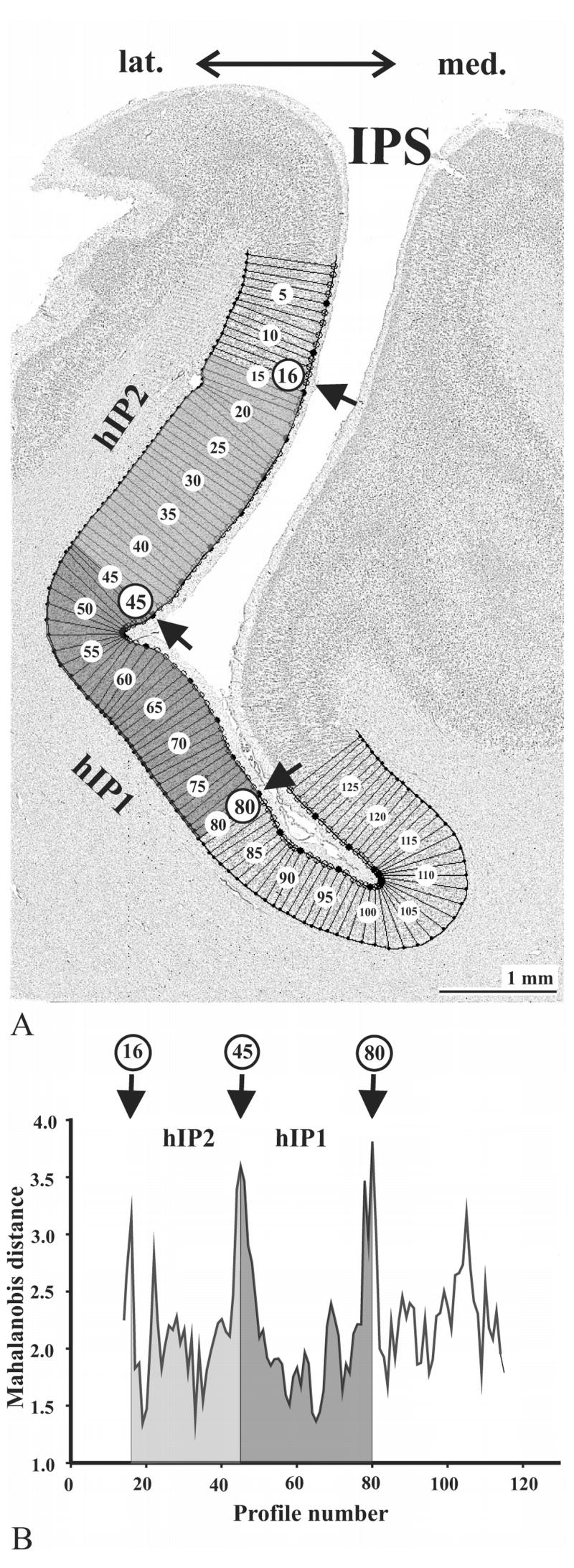

Cortical borders were defined using differences in the grey-level index algorithm (GLI) of the regions and multivariate statistical analysis (Schleicher and Zilles, 1990; Schleicher et al. 1999; Zilles et al., 2002). The GLI, calculated in square 20 x 20 μm fields, is the volumetric proportion of somata per total volume of brain tissue (Wree et al., 1982) and is plotted spatially (Fig 3).

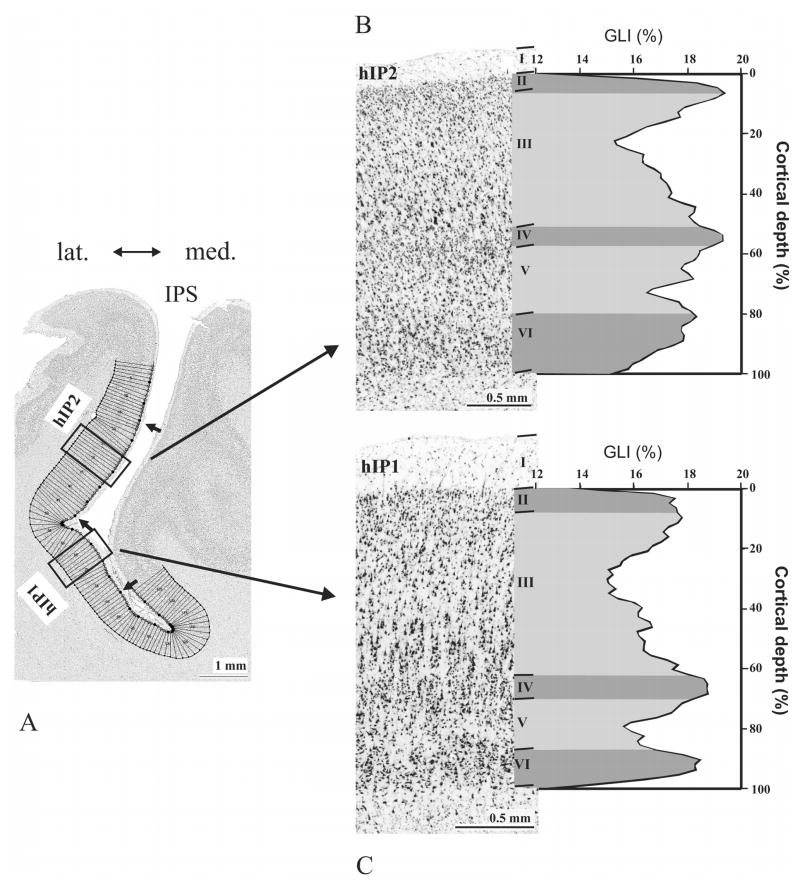

Figure 3.

Observer-independent definition of cytoarchitectonic borders (Schleicher et al., 1999) has been performed in GLI images in cortical regions of interest (A). Dark pixels correspond to high GLI values (high volume fraction of cell bodies), whereas bright pixels correspond to low GLI values (low fraction). GLI profiles were extracted along vertical traverses, and numbered (1 to 129 in this example). Ten features or shape descriptors, based on central moments, were extracted from each profile. Using the multivariate Mahalanobis distance function, borders were defined at the positions where profiles changed significantly in shape. (B) shows a Mahalanobis distance function for neighboring blocks of profiles, each of which contained 14 profiles. Significant distance values were found at positions 16, 45 and 80, marked by arrows in (A) and (B). These positions mark the borders of areas hIP2 and hIP1.

Profiles, the automatically extracted GLI values, are measured perpendicular to the outer cortical contour. To characterize cortices, GLI profiles were produced at equidistant intervals of 128 μm. The profiles were numbered consecutively (Fig. 3A). The borders between layers I/II (outer contour) and between layer VI/white matter (inner contour) were drawn interactively.

The shape of the profiles from layer I/II border to the white matter correlates with the qualitatively observed laminar patterns, i.e., with cytoarchitecture. To quantitatively compare GLI profiles, each was normalized to a cortical depth of 100 % by a linear interpolation. The shape of each profile was quantified using ten features (= feature vector) based on central moments (Pearson, 1936; Dixon et al., 1988). Features included the mean GLI value, the cortical depth of the center of gravity of the profile, the standard deviation, the skewness, the kurtosis, and the analogous parameters for the first derivative of the profile (Schleicher et al. 1999; Amunts et al. 1999). Features were z-normalized in order to assign equal weight to each of the features (Dixon et al., 1988).

The feature vectors of two neighboring sets of profiles with a fixed block size were compared by the Mahalanobis distance (D2). A Hotelling’s t2 test (α = 0.05) was applied for statistical significance. The higher the D2 value between two blocks of profiles, the greater the difference in the laminar pattern, i.e., in cytoarchitecture, and vice versa. The procedure was repeated for different block sizes containing 8 to 20 profiles. Borders between adjacent cytoarchitectonic areas were defined where Mahalanobis distances were significant at a level of α = 0.05 (Fig. 3B), where the positions of borders were the same for different blocksizes, and where borders were found at comparable positions in neighboring histological sections.

Overview images illustrating the cytoarchitecture of hIP1 and hIP2 were processed using the PhotoLine software (version 11.50). A gamma-correction was applied to optimize visualization of photomicrographs.

Statistical analysis of inter-areal and inter-hemispheric differences in GLI profiles

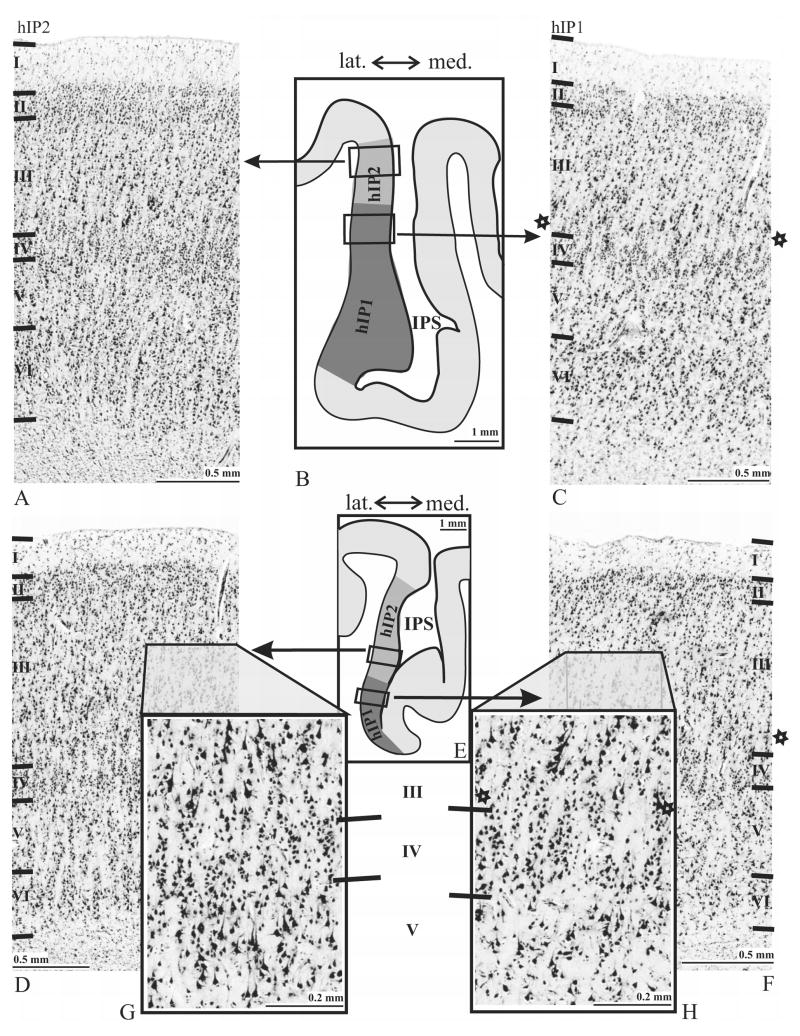

Inter-areal, inter-brain, hemispheric, and left-right cytoarchitectural differences between hIP1 and hIP2 (Fig. 4) were based on sampling at least 6 sections per area and 25–30 profiles per area. Mean profiles of hIP2 and hIP1 per brain and hemisphere (Fig. 5B, C) were calculated, resulting in a total of 40 (2 areas x 10 brains x 2 hemispheres). Mean profiles characterize hIP2 and hIP1.

Figure 4.

Cytoarchitecture of areas hIP2 and hIP1 and intersubject differences in two individual brains No.2 (A–C) and No.9 (D–F). The rectangular frames in the corresponding overview-images (B, E) indicate the regions from which the micrographs were taken from. Note the differences in cell density and cell size in layers III to V between both areas. hIP2 (G) shows a higher volume fraction of cell bodies (GLI) in the deeper part of layer III and upper layer V as compared to hIP1 (H). hIP1 was also found to have a ‘buffering zone’ between layers III and IV which is indicated by stars (C, F, H). Roman numerals indicate cortical layers.

Figure 5.

The mean GLI profile of areas hIP2 and hIP1 as measures of inter-areal differences of one left hemisphere (brain-No.6) and corresponding cytoarchitecture (hIP2: B; hIP1: C). Profiles were sampled in ROIs as indicated in (A). Areal borders are marked by arrows. (B, C) The GLI profiles express laminar changes in volume fraction of cell bodies from a cortical depth of 0 % (border between layers I and II) to a cortical depth of 100 % (white matter border). Note the differences in width of layers III and VI: hIP2 has a narrower layer III and a broader layer VI as compared to hIP1. Roman numerals refer to the cortical layers.

After the profiles were superimposed on the cytoarchitectonic sections, the relative thicknesses of cortical layers II through VI were marked on the profiles. The relative width of each cortical layer was analyzed for both inter- and intra-areal comparisons and hemispheric differences (Table 2) using an ANOVA (10 brains, two hemispheres, two areas, five layers; dependent variable: layer width; main factor: area; within factor: hemisphere; α = 0.05). All tests were corrected for multiple comparisons by applying the Bonferroni-correction.

Table 2.

Relative layer widths (%) of layers II – VI of areas hIP1left/right and hIP2left/right (n = 10).

| hIP1 | hIP2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| left | right | left | right | |

| II | 8.4 | 8.9 | 8.0 | 9.3 |

| III | 45.5 | 45.4 | 37.3 | 38.4 |

| IV | 7.4 | 7.4 | 8.3 | 8.3 |

| V | 19.1 | 19.1 | 22.0 | 21.3 |

| VI | 19.6 | 19.2 | 24.4 | 22.7 |

The layer width of layer III was significantly greater in hIP1compared to hIP2.

Volume measurements

The volumes (Fig. 6) of the areas (2 areas x 10 brains x 2 hemispheres) were estimated stereologically from histological sections by applying Cavalieri's principle (Uylings et al., 1986; Amunts et al. 1999). Depending on the extent of the two areas within each brain, 10–17 equidistant sections were analyzed for each hemisphere. Inter-hemispheric differences of the volume of each area were tested by a paired t-test, as well as inter-areal differences, i.e., hIP1 vs. hIP2.

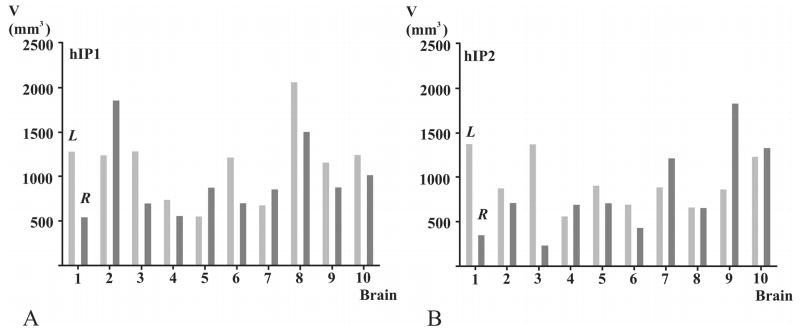

Figure 6.

Volumes (mm3; ordinate) occupied by hIP1 (A) and hIP2 (B) of each brain (abscissa). Light gray - L: left hemisphere, dark gray - R: right hemisphere. Note the high inter-individual variability of volumes for areas hIP1 and hIP2. The volumes of hIP1 differed by a factor of 4 on the left hemisphere and by a factor of 3 on the right hemisphere. The volumes of hIP2 varied by a factor of 3 on the left hemisphere and by a factor of 5 on the right hemisphere. Inter-hemispheric differences were not significant.

Location of areas

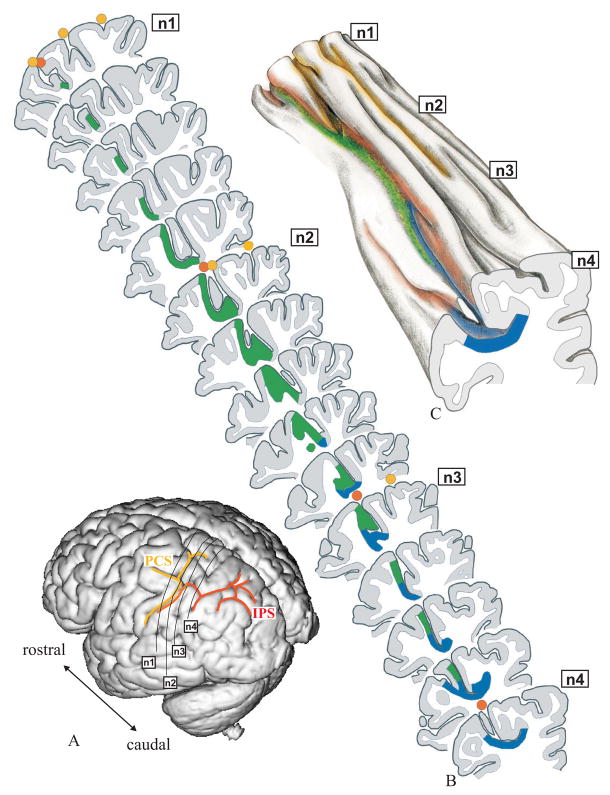

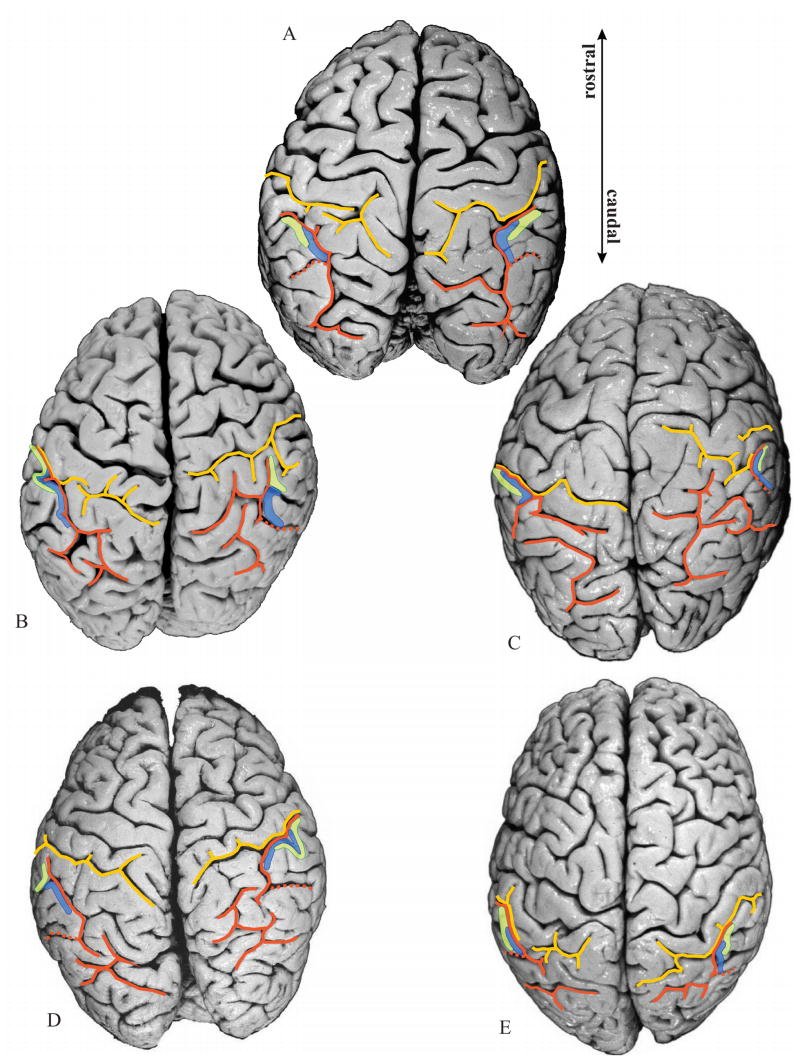

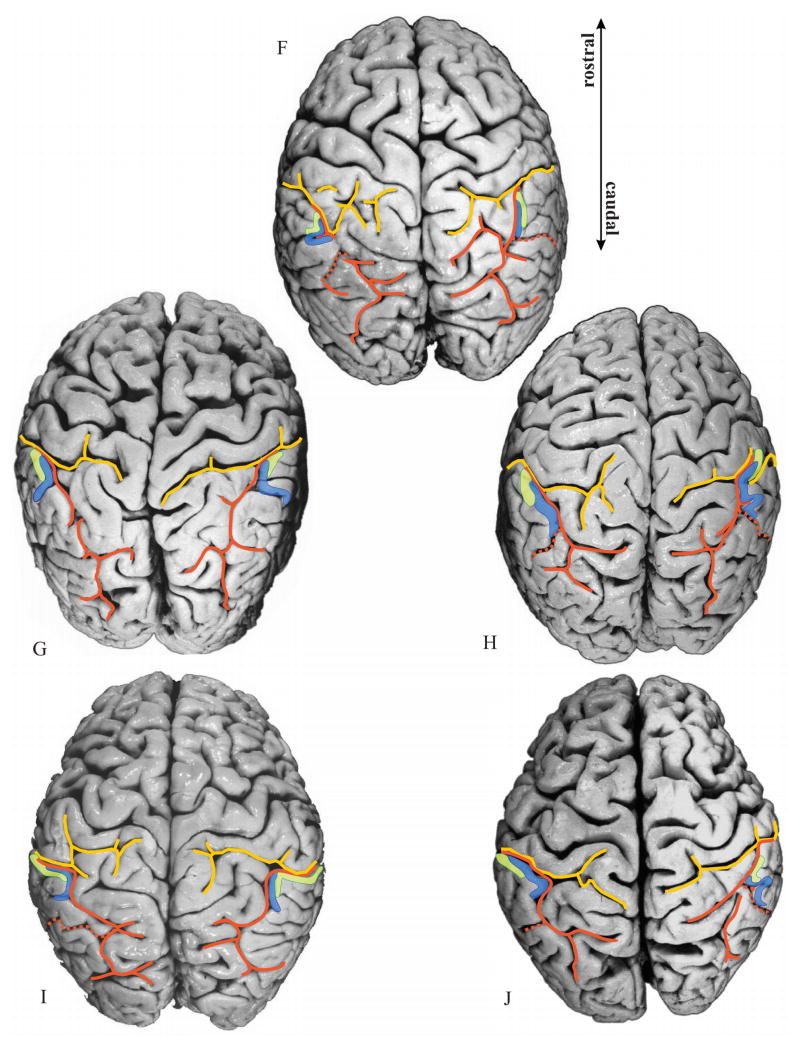

The IPS and PCS were identified according to Ono et al. (1990). The IPS has a complex pattern, with many small dimples and folds (Fig. 8B-C). The folds are often located in its depth and not visible from outside.

Figure 8.

The location of areas hIP1 and hIP2 in an individual brain (No.9, Table 1). (A) Surface rendering of the 3D-reconstructed postmortem brain; view from left, posterior, lateral. Note that in this case the PostCentral Sulcus (PCS, yellow) and the IntraParietal Sulcus (IPS, orange) are connected. Solid black lines on the surface of the brain mark the approximate location of 4 histological sections (n1-n4) also indicated in B – D. (B) Drawings of 15 serial histological sections (left hemisphere). Areas hIP1 (blue) and hIP2 (green) are marked. (C) 3D-reconstruction enabling an insight into the depth of the sulcal pattern of the IPS and PCS. Note the numerous dimples and foldings within the IPS. Both sulci show a complex pattern, which cannot be obtained from the inspection of the free surface of the brain alone. The IPS originates in a side branch of the PCS, which is located much more anteriorly than its appearance on the surface of the brain. (D) The topography of areas hIP2 and hIP1 in a “flat map”. Both areas are located in the lateral bank of the IPS. hIP2 lies more rostrally and laterally from hIP1. The assumed topographic relationship of areas hIP2 and hIP1 to surrounding Brodmann’s areas is shown. His area 2 (BA2; Grefkes et al. 2001), 5 (BA 5) and 7 (BA 7) are most likely to be found at this location independent from hIP2 and hIP1 in accordance with cytoarchitectonic studies of the human parietal cortex. Solid lines mark the fundus of a sulcus, dotted lines indicate the free surface of a gyrus.

The precise topography of areas within the depth of the IPS was visualized by means of flat-maps (Fig. 8D). They were created by: (i) drawing a vertical line for each 60th histological section, (ii) transferring the distances from the sulcal fundus to the gyral crown, from the medial and lateral borders of the areas, and from the extent of a gyrus on the free surface of the brain to the vertical lines and marking them by different symbols, and (iii) connecting the corresponding symbols into lines. The maps indicate the cortical area, the sulcal fundus and the free surface of a gyrus within a sequence of sections (Fig. 8B). In order to visualize the complex pattern of the IPS in the depth of the sulcus, a 3D-reconstruction of a sequence of histological sections was drawn for one hemisphere (Fig. 8C).

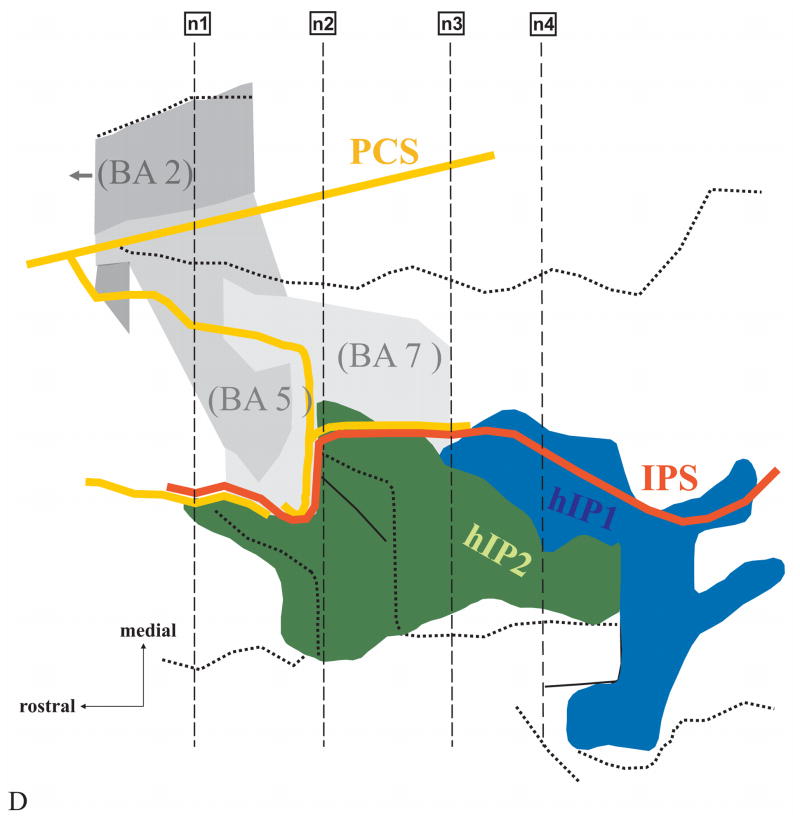

Probabilistic maps

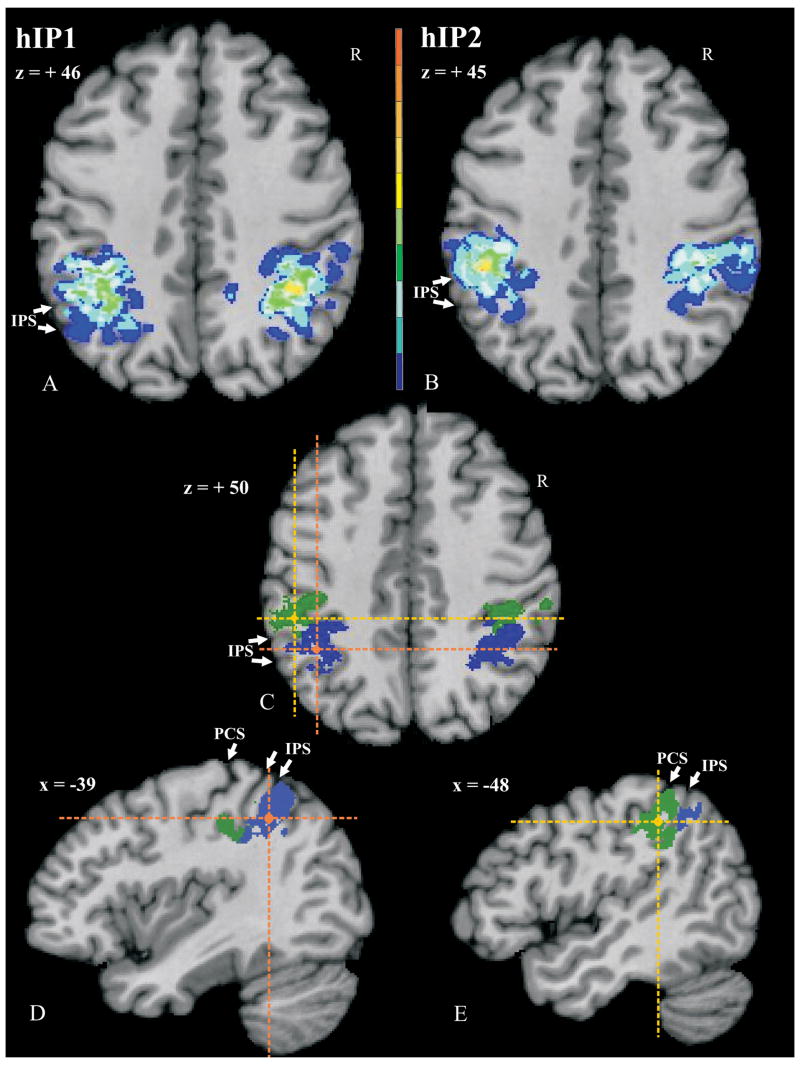

The cytoarchitectonically defined areas were reconstructed into 3D voxels and transformed to the commen reference space. Cytoarchitectonic probability maps (Fig. 9A, B; Roland and Zilles, 1994) were calculated by superimposing the areas from all ten brains within the common reference space, with each voxel showing the frequency that the area was present in the sample of the ten brains. Based on these maps, 40% maps were calculated (Fig. 9C–E); i.e., each region displays the voxels which have an overlap by 4 or more brains.

Figure 9.

Probability maps of the left hemisphere of areas hIP1 (A) at z = +46 and hIP2 (B) at z = +45. Maps are shown in the anatomical MNI-space with the AC as the origin (0/0/0) of the coordinate system according to the system of Talairach and Tournoux (1988). The number of overlapping brains is color-coded for each voxel. It ranges from dark blue (hIP1/hIP2 represented in 1 of 10 brains) to dark red (hIP1/hIP2 represented in all 10 brains). Note the high variability in location of both areas. (C) shows a horizontal section of the 40% maps of hIP1 (blue) and hIP2 (green) within one brain at z = +50. Crosses mark the level of corresponding sagittal sections of hIP1 (orange; D) at x = −39 and hIP2 (yellow; E) at x = −48. Note the topographical relationship between hIP2 and hIP1 in the rostro-caudal plane: hIP2 is located rostrally from hIP1. PCS, IPS – white arrowheads.

Results

Cytoarchitecture

Two cytoarchitectonic areas, hIP1 and hIP2, were identified. They differed between each other and with the surrounding cortex (Figs. 4–5). Area hIP1 (Figs. 4C, F) is characterized as follows: layer II of hIP1 is narrow. The border between layers II and III is subtle, due to pyramidal cells of layer III intermingling with those of layer II. Layer III is broad and has large pyramidal cells in its lower part. A lightly packed zone in deep layer III has a lower cell density than the remaining parts of layers III and IV. Layer IV has densely packed granular cells. The mean size of layer V pyramidal cells is smaller than those of layer III. Both cell density and size of cells decrease toward the lower part of layer V. Layer VI is more densely packed than layer V. The white matter border is sharp.

Area hIP2 (Figs. 4A, D) shows a densely packed layer II. The border of layer II and III is fuzzy due to intermingling neurons from layer III into layer II. Layer III has varying sized pyramidal cells. The mean size of pyramidal cells as well as the cell density increases towards layer IV. The border between layers III and IV is sharp. Layer IV is narrow and densely packed. The layer IV–V border is subtle since large pyramidal cells of layer V intermingle with granular cells of layer IV. The pyramidal cells of layer V are densely packed at the transitions to both layers IV and VI. Layer VI is approximately as thick as layer V. The border between layer V and VI is fairly prominent. The cells are densely packed in layer VI, particularly in its upper part.

The cell densities of layers III and V provide the main differences between hIP2 and hIP1: hIP2 has a higher density of cells in lower layer III and upper layer V than hIP1. In addition, hIP2 has larger pyramidal cells in upper layer V than does hIP1 (compare Fig. 4G vs. 4H).

Inter-areal and inter-hemispheric differences

Differences between hIP2 and hIP1 were quantified using the GLI profiles (Fig. 5). The GLI profiles of hIP2 and hIP1 have three local maxima. They share two local maxima; one at the border between layers II and III, and one at layer IV. The third local maximum differs between the two cortices; hIP2 has a GLI maximum between layers V and VI, whereas in hIP1 the third maximum is found at layer VI. The maximum at the border between layers II and III was higher in IP2 than in IP1 in most of the brains (Fig. 5).

Analysis of the width of each cortical layer of the two areas (Table 2) showed that hIP2 has a significantly narrower layer III than hIP1. Layers IV, V and VI tend to be broader in hIP2 than in hIP1. Layer II has a nearly similar width in both areas. There is no effect of hemisphere (left/right) on layer width.

Cytoarchitectonic differences between the two areas were also reflected in the z-normalized feature vectors (averaged over all ten brains per area and hemisphere). Areas hIP1 and hIP2 revealed a greater difference from each other than the corresponding areas of the right and left hemispheres. The analysis of the z-normalized feature vectors also showed that features meanx.d, skew.d and kurt.o contribute in particular to inter-areal differences. The differences between areas hIP1 and hIP2 in these features were −1.21, 1.09 and 1.03, respectively. Differences for the remaining seven features were smaller (< 0.9), and differences in mean GLI had only a value of 0.12 (minimal difference).

Volumes

The volumes of both cortical areas varied considerably between subjects, up to a factor of 5 (Fig. 6). The volumes of hIP1 varied from 530 mm3 to 2,050 mm3 (mean: 1,134 mm3, SD = ∀ 427) in the left hemisphere, and from 532 mm3 to 1,848 mm3 (mean: 939 mm3, S.D. = ∀ 422) in the right hemisphere. The volumes of hIP2 ranged from 548 mm3 to 1,366 mm3 (mean: 932 mm3, SD = ∀ 290) in the left hemisphere and from 341 mm3 to 1,822 mm3 (mean: 807 mm3, SD = ∀ 497) in the right hemisphere.

Topography of hIP2 and hIP1

Three main aspects contributed highly to the great variability of the exact topography of areas hIP1 and hIP2: the existence of a sulcal connection between the IPS and PCS, the number of segments of IPS (Table 3) and the relationships of hIP1 and hIP2 to neighboring areas.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the topological pattern of the IPS (n = 10)

| left hemisphere | right hemisphere | |

|---|---|---|

| Connected with the PCS | 80% | 90% |

| Number of segments of the IPS: | ||

| 1 segment | 50% | 50% |

| 2 segments | 40% | 40% |

| 3 segments | 10% | 10% |

| Existence of IMPS | 70% | 80% |

1. Connection of IPS and PCS

The IPS and PCS are connected in 8 left and 9 right hemispheres (Fig. 7), and not connected in the remaining 3 hemispheres.

Figure 7.

Delineated areas hIP1 (blue) and hIP2 (green) are projected onto photographs of the dorsal surface of the 10 delineated postmortem brains. Note the considerable intersubject variability in the pattern of the IPS (orange) and PCS (yellow), as well as the variability in location and extent of both areas. Orange dotted line: IMPS, the side branch of the IPS, which divides the supramarginal gyrus from the angular gyrus. Note that in the caudal direction hIP1 does not extend beyond this side branch.

When IPS and PCS are connected: The analysis of histological sections (Fig. 8B) of these hemispheres revealed that the course of the IPS in the depth of the sulcus (Fig. 8C) differed considerably from the sulcal pattern as seen on the surface of the brain (Fig. 8A). The anterior part of the IPS originates from a side-branch of the PCS and caudally forms the IPS. Thus the actual beginning of the IPS is in the depth of the brain and may be located up to 12 mm anterior to its surface occurrence (Fig. 8A). hIP1 and hIP2 started in the “transitional” region of IPS and PCS with hIP2 being more anterior than hIP1.

When IPS and PCS are not connected (Figs. 7A, D, left hemisphere; 7B, right hemisphere): Both hIP regions were located within the IPS, and the lengths of both the sulci on the free surface and in the depth of the sulcus were equivalent. This contrasts to the case where the sulci were connected. Area hIP2 starts in the most anterior part of the IPS, where the supramarginal gyrus forms the lateral bank of the IPS.

2. Relationship of hIP2 and hIP1 to sulci (IPS, PCS)

The IPS forms one segment in 7 brains (Figs. 7A, B, H, I, J, left hemisphere; 7A, F, G, H, I, right hemisphere). Regardless of the number of segments, hIP2 and hIP1 were always found in the most anterior part of the IPS, with hIP2 being anterior and lateral to hIP1. If the IPS consists of two to three segments (Figs. 7C, D, E, F, G, left hemisphere; 7B, C D, E, J, right hemisphere), as was found in 7 brains, areas hIP2 and hIP1 were always located in the most anterior segment. In these cases as well, hIP2 is anterior and lateral to hIP1.

Anterior part of hIP2: In 7 left hemispheres (Figs. 7B, C, F, G, H, I, J) and 6 right hemispheres (Figs. 7C, D, G, H, I, J) of 8 brains projections onto the brain surface showed that the anterior part of hIP2 is located in the PCS rather than in the IPS (Ono et al. 1990) or in the descending segment of the intraparietal sulcus when applying the nomenclature of Duvernoy and Vannson (1999). More caudally, this branch would be labeled as IPS. Posterior part of hIP2: In 2 hemispheres of 2 brains (Figs. 7J, left hemisphere; 7H, right hemisphere), projections onto the surface of the brain revealed that hIP2 ends within the PCS. In the remaining cases, the caudal part of hIP2 was fully located within the IPS.

Anterior part of hIP1: hIP1 reached the PCS in 8 left hemispheres (Figs. 7B, C, E, F, G, H, I, J) and 6 right hemispheres (Figs. 7A, C, D, E, G, H), i.e., in 10 brains. In the remaining hemispheres, the anterior part of hIP1 always lay completely within the IPS. Posterior part of hIP1: In all cases, hIP1 ended within the IPS.

3. Relationship of hIP2, hIP1 to neighboring cortical areas

hIP2: The most anterior part of hIP2 was always located in the fundus of the sulcus. In some hemispheres, this part extended to the medial bank of the IPS at a level before hIP1 appeared. The comparison in 6 brains, which were mapped both in our studies and the study of Brodmann’s area 2 by Grefkes et al. (2001), showed that the most anterior tip of hIP2 lay next to Brodmann’s area 2 in 1 left hemisphere and 2 right hemispheres. This spatial relationship was observed in a short rostro-caudal region of 1–2 mm width. Caudally, two parietal areas were found between area hIP2 and Brodmann’s area 2. Based on external references these areas belong possibly to Brodmann’s areas 5, 7 (1909) and/or the Medial IntraParietal area MIP as found in the nonhuman primate brain (Lewis and Van Essen, 2000a). They were located medially to hIP2 and anterior to hIP1. This relationship was found in the remaining 5 left hemispheres and 4 right hemispheres through the whole extent of hIP2. Area hIP2 was found along the lateral bank toward the free surface of the inferior parietal lobule, partially reaching the crown of the lobule at its caudal ending.

hIP1: hIP1 was located caudally and medially to hIP2. It lay in the fundus of the IPS mostly occupying its lateral bank. It reached the medial bank, more caudally. The caudal border of area hIP1 was found in the sulcus intermedius primus, which is also known as the Jensen sulcus. The Jensen sulcus has been described as the dorsal branch of the IPS, which divides the inferior parietal lobule into the supramarginal and the angular gyrus. The caudal ending of hIP1 did not extend beyond, i.e., caudally, the Jensen sulcus.

Probability maps

The probability maps of areas hIP1 (Fig. 9A) and hIP2 (Fig. 9B) quantified the intersubject variability in location and size, as well as the topographical relationship between the two areas in stereotaxic space. The intersubject variability in extent and location of both areas was considerable in both hemispheres. The probability map of area hIP1 revealed a maximum overlap of 7 brains in the left hemisphere and 7 brains in the right hemisphere. The probability map of hIP2 showed a maximal overlap of 7 brains in the left hemisphere, and 5 brains in the right hemisphere. According to the anatomical MNI space, the centers of gravity of both areas were at (−39/- 55/46) for hIP1 and at (−47/-43/45) for hIP2 on the left hemisphere, and at (39/ -53/47) for hIP1 and at (45/-42/48) for hIP2 on the right hemisphere. That is, hIP1 is located more posteriorly and medially than hIP2.

Discussion

Three major sources of data from the literature are encountered when evaluating the present mapping data of the anterior ventral bank of the human IPS: First, historical cytoarchitectonic investigations of the human IPS; second the intraparietal areas described in the macaque brain; and third functional imaging studies (fMRI, PET) identifying equivalent areas in the human IPS. These three sources, however, cannot be compared directly to each other. Problems arise from the different sulcal complexities of the macaque and human brain, as well as the unresolved homology between macaque and human cortical areas. Functional imaging data in the human brain have only been interpreted with respect to stereotaxic coordinates and brain macroscopy, but not with respect to microstructurally defined areas.

To understand the location, extent and varying topography of areas found in the anterior ventral bank of the human IPS, it was necessary to investigate the sulcal pattern of the IPS in detail. The pattern of the IPS can roughly be described as running perpendicularly towards the PCS. The sulci can intersect more ventrally or dorsally on the brain. The IPS may originate from a side branch of the PCS and thus they may coexist in the depth of the brain, although on the surface this zone appeared as only one sulcus. The situation is different and to some extent less complex in nonhuman primate brains, where the PCS is absent in some species (Paxinos et al., 1999). The human IPS can express a variable number of side branches, which differ considerably in length, and which are not always visible on the surface of the brain. Moreover, the IPS itself may consist of up to 3 segments. In these hemispheres, we had to investigate whether the segments were interconnected within the sulcal depths. The highly variable pattern of the IPS indicated that there is no such thing as ‘the typical pattern of the IPS’, at least not in the depth of the sulcus.

The complex characteristics of the individual sulcal patterns aggravated the following of areal borders and thus may well have been part of the reason why historical brain maps have either resulted in a simplification of the human IPS (Brodmann, 1909; von Economo and Koskinas, 1925) or an over-parcellation (Gerhardt, 1940) of the same region. Given the technical constraints of this period, changes in cytoarchitecture were probably regarded as caused by the gyral and sulcal pattern, rather than caused by different cytoarchitecture. On the other extreme, depending on the observer, each change in cytoarchitectonic appearance could be regarded as primarily caused by cytoarchitectonic different areas with little consideration of the sulcal pattern.

Using an algorithm-based approach for the definition of areal borders, we delineated two areas, hIP1 and hIP2 in all ten postmortem brains. They had consistent cytoarchitectonic characteristics as well as a consistent topographic relationship towards each other. hIP2 was located in the most anterior part of the IPS extending to the lateral bank of the sulcus. Area hIP1 was found posterior and medial to hIP2, yet also on the lateral bank of the IPS. The centers of gravity from the probability maps of each area further showed that hIP2 also tends to be located inferior to hIP1. This is not surprising, considering that the most anterior part of the IPS and, therefore, the main part of hIP2, is often located in, or parallel to, the inferior part of the PCS.

Our cytoarchitectonic analysis revealed significant differences between the two areas in the laminar pattern. These differences include (i) a broader and lesser cell density of layer III in hIP1 than in hIP2, and (ii) a higher local maximum in the GLI profiles at the level of layer II in hIP2 than in hIP1. This leads to a relative “overweight” of hIP2 compared to hIP1 in the superficial portion of the cortical cross section over the deeper portion (compare the two profiles in Figure 5; the area occupied by the GLI profile is larger in the superficial portion of hIP2 than in hIP1). Such a relationship between superficial and deep parts of the cortical cross section is captured by the values of the z-normalized features meanx.d and skew.d (Zilles et al., 2002; Amunts et al., 2003). Lower GLI values in layer III in combination with a broader relative thickness is an indicator of more neuropil in hIP1 than in hIP2, i.e., of more space for synapses, dendrites and axons. This can be interpreted with respect to more interareal, transcallosal connectivity in hIP1 than in hIP2.

The probability maps showed that the location and extent of both areas in the reference space varied considerably, however. Although probability maps are primarily interpreted in terms of the microstructural variability of areas hIP1 and hIP2, they may also reflect variability in the sulcal pattern of the IPS as well as methodical aspects of the non-linear registration algorithm. This is true not only in our cytoarchitectonic study, but also in any functional imaging study.

A preliminary interpretation of the functions of the two delineated areas can be determined on the basis of imaging studies of the human brain (Table 4). Recent studies reported, in analogy to the macaque cortex, the identification of areas AIP (Grafton et al., 1996; Binkofski et al., 1998; Jäncke et al., 2001; Grefkes et al. 2002), VIP (Bremmer et al. 2001), MIP (Grefkes et al., 2004), LIP (Heide et al., 2001; Sereno et al., 2001; Koyama et al., 2004) and PIP (Taira et al., 1998; Faillenot et al. 1999; Shikata et al., 2001, 2003). For an overview see Grefkes and Fink (2005). The location of hIP1 and hIP2 at the lower bank of the anterior IPS, their relationship to each other, as well as their stereotaxic location suggest that VIP and AIP are putative functionally defined correlates of the architectonically defined areas.

Table 4.

Overview of stereotaxic coordinates of cytoarchitectonic areas hIP1, hIP2 and local maxima of activations found in functional imaging studies.

| left hemisphere | right hemisphere | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | x | y | z | |

| 1 hIP1 (this study) | −39 | −55 | 46 | 39 | −53 | 47 |

| 1 hIP2 (this study) | −47 | −43 | 45 | 45 | −42 | 48 |

|

| ||||||

| 2 hAIP (Binkofski et al., 1998) | −45 | −35 | 43 | |||

| 2 hAIP (Jäncke et al., 2001) | −44 | −32 | 40 | 40 | 32 | 40 |

| 2 hAIP (Grefkes et al., 2002) | −40 | −42 | 36 | |||

| 2 hVIP (Bremmer et al., 2001) | −40 | −40 | 42 | 38 | −44 | 46 |

| 3 hMIP (Grefkes et al., 2004) | −28 | −50 | 52 | 28 | −56 | 50 |

| 2 hLIP (Koyama et al., 2004) | −20 | −63 | 49 | 19 | −63 | 49 |

| 2 hPIP (Shikata et al., 2003) | − 9 | −75 | 54 | 21 | −66 | 60 |

Coordinates in anatomical MNI-space, i.e., (0/0/0) is at the anterior commissure

Coordinates in the reference space as defined by Talairach and Tournoux (1988), (0/0/0) at the anterior commissure

Coordinates in the standard MNI-space

A comparison of the present map with that of the macaque cortex shows, however, that the situation can be more complex: Area VIP in macaques was subdivided into a medial (VIPm) and a lateral (VIPl) part (Lewis and Van Essen, 2000a, b). A similar cytoarchitectonic subdivision of area hIP1 (or hIP2), however, has not been detected. At least two interpretations can be suggested: (i) only one of the two macaque areas, either VIPm or VIPl, correlates with hIP1, whereas the other area belongs to the part of the IPS which is still uncharted. (ii) hIP1 and hIP2 correspond to VIPm and VIPl, respectively. If the second interpretation is true, hIP2 does not correspond to AIP. Other interpretations and combinations are possible. The solution of this problem depends to a large extent on the unresolved homology of the macaque and human IPS cortex, which can only be solved once the IPS has been completely mapped.

Apart from these questions of homology, the functional role of the intraparietal region has not been unambiguously defined. In addition to visuo-motor and visuo-spatial functions, the IPS is also involved in numerical processing (Pinel et al. 1999, 2001; Eger et al. 2002; Simon et al., 2002; Dehaene et al. 2003; Nieder, 2004). Another study demonstrated activations within the IPS in paradigms related to spatial working memory and object working memory (Belger et al., 1998). Thus, different functional concepts have been forwarded with respect to the role of intraparietal cortical areas. As a consequence, the interpretation of our architectonically defined areas depends not only on comparative anatomical studies, but also on our progress in defining the function of this cortical region.

Cytoarchitectonic probabilistic maps are freely available for the neuroscientific community, and activations obtained in imaging studies using fMRI and PET can easily be compared with maps using a new SPM anatomy toolbox (Eickhoff et al., 2005). The probabilistic maps supplement existing maps of other cortical regions and subcortical nuclei, e.g., those of the anterior parietal cortex (Geyer et al., 1999, 2000; Grefkes et al., 2001). They may open new perspectives for structural-functional comparison in the IPS in the human brain, and support the generation of hypotheses about the structural and functional segregation of the parietal cortex.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded partly by the Human Brain Project/Neuroinformatics research (National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institute of Mental Health; grant to K.Z., K.A.), the DFG (Klinische Forschergruppe KFO 112; grants to K.Z. and G.F.), the European Community (grant QLG3-CT-2002-00746 to K.Z.) and the Helmholtz Gemeinschaft (VH-NG-012, grant to K.A.). The authors would also like to thank Christine Opfermann-Rüngeler for the art work and Carol McLeod for helpful suggestions and stimulating discussions, and Ursula Blohm and Ferdag Kocaer for expert technical assistance.

Reference List

- Amunts K, Schleicher A, Bürgel U, Mohlberg H, Uylings HB, Zilles K. Broca's region revisited: cytoarchitecture and intersubject variability. J Comp Neurol. 1999;412:319–341. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19990920)412:2<319::aid-cne10>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amunts K, Schleicher A, Ditterich A, Zilles K. Broca's region: cytoarchitectonic asymmetry and developmental changes. J Comp Neurol. 2003;465:72–89. doi: 10.1002/cne.10829. Erratum in: J Comp Neurol. 467:270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amunts K, Weiss PH, Mohlberg H, Pieperhoff P, Eickhoff S, Gurd JM, Marshall JC, Shah NJ, Fink G, Zilles K. Analysis of neural mechanisms underlying verbal fluency in cytoarchitectonically defined stereotaxic space-The roles of Brodmann areas 44 and 45. NeuroImage. 2004;22:42–56. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen RA, Brotchie PR, Mazzoni P. Evidence for the lateral intraparietal area as the parietal eye field. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1992;2:840–846. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(92)90143-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong E, Zilles K, Schlaug G, Schleicher A. Comparative aspects of the primate posterior cingulate cortex. JCompNeurol. 1986;253:539–548. doi: 10.1002/cne.902530410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barash S, Bracewell RM, Fogassi L, Gnadt JW, Andersen RA. Saccade-related activity in the lateral intraparietal area. I. Temporal properties; comparison with area 7a. J Neurophysiol. 1991a;66:1095–1108. doi: 10.1152/jn.1991.66.3.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barash S, Bracewell RM, Fogassi L, Gnadt JW, Andersen RA. Saccade-related activity in the lateral intraparietal area. II. Spatial properties. J Neurophysiol. 1991b;66:1109–1124. doi: 10.1152/jn.1991.66.3.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belger A, Puce A, Krystal JH, Gore JC, Goldman-Rakic P, McCarthy G. Dissociation of mnemonic and perceptual processes during spatial and nonspatial working memory using fMRI. Hum Brain Mapp. 1998;6:14–32. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0193(1998)6:1<14::AID-HBM2>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binkofski F, Dohle C, Posse S, Stephan KM, Hefter H, Seitz RJ, Freund HJ. Human anterior intraparietal area subserves prehension: a combined lesion and functional MRI activation study. Neurology. 1998;50:1253–1259. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.5.1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremmer F, Schlack A, Shah NJ, Zafiris O, Kubischik M, Hoffmann K, Zilles K, Fink GR. Polymodal motion processing in posterior parietal and premotor cortex: a human fMRI study strongly implies equivalencies between humans and monkeys. Neuron. 2001;29:287–296. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00198-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodmann K. Vergleichende Lokalisationslehre der Großhirnrinde. Leipzig: Barth; 1909. [Google Scholar]

- Buxhoeveden D, Lefkowitz W, Loats P, Armstrong E. The linear organization of cell columns in human and nonhuman anthropoid Tpt cortex. Anat Embryol. 1996;194:23–36. doi: 10.1007/BF00196312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavada C, Goldman-Rakic PS. Posterior parietal cortex in rhesus monkey: II. Evidence for segregated corticocortical networks linking sensory and limbic areas with the frontal lobe. J Comp Neurol. 1989;287:422–445. doi: 10.1002/cne.902870403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen YE, Andersen RA. A common reference frame for movement plans in the posterior parietal cortex. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:553–562. doi: 10.1038/nrn873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colby CL, Duhamel JR, Goldberg ME. Ventral intraparietal area of the macaque: anatomic location and visual response properties. J Neurophysiol. 1993;69:902–914. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.69.3.902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colby CL, Goldberg ME. Space and attention in parietal cortex. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1999;22:319–349. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.22.1.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins DL, Neelin P, Peters TM, Evans AC. Automatic 3D intersubject registration of MR volumetric data in standardized Talairach space. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1994;18:192–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly CJ. External morphology of the primate brain. Springfield: Thomas; 1950. External morphology of the primate brain; pp. 204–222. [Google Scholar]

- Coull JT, Frith CD. Differential activation of right superior parietal cortex and intraparietal sulcus by spatial and nonspatial attention. Neuroimage. 1998;8:176–187. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1998.0354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham DJ. Contribution to the surface anatomy of the cerebral hemispheres. Dublin: Royal Irish Academy; 1882. [Google Scholar]

- de Jong BM, van der Graaf FH, Paans AM. Brain activation related to the representations of external space and body scheme in visuomotor control. Neuroimage. 2001;14:1128–1135. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehaene S, Piazza M, Pinel P, Cohen L. Three parietal circuits for number processing. Cogn Neuropsychology. 2003;20:487–506. doi: 10.1080/02643290244000239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon WJ, Brown MB, Engelman L, Hill MA, Jennrich RI. BMDP: Statistical Software Manual. Berkely: Univ. of California Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Duvernoy HM, Vannson JL. The human brain - surface, three dimensional sectional anatomy with MRI, and blood supply. Wien: Springer; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ebeling U, Steinmetz H. Anatomy of the parietal lobe: mapping the individual pattern. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1995;136:8–11. doi: 10.1007/BF01411428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eger E, Sterzer P, Russ MO, Girald AL, Kleinschmidt A. A supramodal number representation in human intraparietal cortex. Neuron. 2002;37:719–725. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00036-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eickhoff S, Stephan KE, Mohlberg H, Grefkes C, Fink G, Amunts K, Zilles K. A new SPM toolbox for combining probabilistic cytoarchitectonic maps and functional imaging data. NeuroImage. 2005;25:1325–1335. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskandar EN, Assad JA. Dissociation of visual, motor and predictive signals in parietal cortex during visual guidance. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:88–93. doi: 10.1038/4594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskandar EN, Assad JA. Distinct nature of directional signals among parietal cortical areas during visual guidance. J Neurophysiol. 2002;88:1777–1790. doi: 10.1152/jn.2002.88.4.1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans AC, Collins DL, Mills SR, Brown ED, Kelly RL, Peters TM. 3D statistical neuroanatomical models from 305 MRI volumes. IEEE conference record Nuclear Science Symposium and Medical IMaging Conference; New York NY. USA. 1993. pp. 1813–1817. [Google Scholar]

- Faillenot I, Decety J, Jeannerod M. Human brain activity related to the perception of spatial features of objects. NeuroImage. 1999;10:114–124. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1999.0449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallese V, Murata A, Kaseda M, Niki N, Sakata H. Deficit of hand preshaping after muscimol injection in monkey parietal cortex. Neuroreport. 1994;5:1525–1529. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199407000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer S, Schleicher A, Zilles K. Areas 3a, 3b, and 1 of human primary somatosensory cortex: I. Microstructural organisation and interindividual variability. Neuroimage. 1999;10:63–83. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1999.0440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer S, Schormann T, Mohlberg H, Zilles K. Areas 3a, 3b, and 1 of human primary somatosensory cortex: II. Spatial normalization to standard anatomical space. 2000. Neuroimage. 11:684–696. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2000.0548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhardt E. Die Cytoarchitektonik des Isocortex parietalis beim Menschen. J Psychol Neurol. 1940;49:367–419. [Google Scholar]

- Gnadt JW, Andersen RA. Memory related motor planning activity in posterior parietal cortex of macaque. Exp Brain Res. 1988;70:216–220. doi: 10.1007/BF00271862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grafton ST, Arbib MA, Fadiga L, Rizzolatti G. Localization of grasp representations in humans by positron emission tomography. 2. Observation compared with imagination. Exp Brain Res. 1996;112:103–111. doi: 10.1007/BF00227183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grefkes C, Geyer S, Schormann T, Roland PE, Zilles K. Human somatosensory area 2: observer-independent cytoarchitectonic mapping, interindividual variability, and population map. NeuroImage. 2001;14:617–631. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grefkes C, Weiss PH, Zilles K, Fink GR. Crossmodal processing of object features in human anterior intraparietal cortex: an fMRI study implies equivalencies between humans and monkeys. Neuron. 2002;35:173–184. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00741-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grefkes C, Ritzl A, Zilles K, Fink GR. Human medial intraparietal cortex subserves visuomotor coordinate transformation. Neuroimage. 2004;23:1494–1506. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grefkes C, Fink G. Functional organization of the intraparietal sulcus in humans and monkeys. J Anat. 2005;207:3–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2005.00426.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris IM, Egan GF, Sonkkila C, Tochon-Danguy HJ, Paxinos G, Watson JD. Selective right parietal lobe activation during mental rotation: a parametric PET study. Brain. 2000;123:65–73. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haug H. Brain sizes, surfaces, and neuronal sizes of the cortex cerebri: a stereological investigation of man and his variability and a comparison with some mammals (primates, whales, marsupials, insectivores, and one elephant) Amer J Anat. 1987;180:126–142. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001800203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heide W, Binkofski F, Seitz RJ, Posse S, Nitschke MF, Freund HJ, Kompf D. Activation of frontoparietal cortices during memorized triple-step sequences of saccadic eye movements: an fMRI study. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;13:1177–1189. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes CJ, Hoge R, Collins L, Woods R, Toga A, Evans AC. Enhancement of MR Images using registration for signal Averaging. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1998;22:324–333. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199803000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jäncke L, Kleinschmidt A, Mirzazade S, Shah NJ, Freund HJ. The role of the inferior parietal cortex in linking the tactile perception and manual construction of object shapes. Cereb Cortex. 2001;11:114–121. doi: 10.1093/cercor/11.2.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson PB, Ferraina S, Bianchi L, Caminiti R. Cortical networks for visual reaching: physiological and anatomical organization of frontal and parietal lobe arm regions. Cereb Cortex. 1996;6:102–119. doi: 10.1093/cercor/6.2.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyama M, Hasegawa I, Osada T, Adachi Y, Nakahara K, Miyashita Y. Functional magnetic resonance imaging of macaque monkeys performing visually guided saccade tasks: comparison of cortical eye fields with humans. Neuron. 2004;41:795–807. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00047-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JW, Van Essen DC. Mapping of architectonic subdivisions in the macaque monkey, with emphasis on parieto-occipital cortex. J Comp Neurol. 2000a;428:79–111. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20001204)428:1<79::aid-cne7>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JW, Van Essen DC. Corticocortical connections of visual, sensorimotor, and multimodal processing areas in the parietal lobe of the macaque monkey. J Comp Neurol. 2000b;428:112–137. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20001204)428:1<112::aid-cne8>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maunsell JH, Van Essen DC. The connections of the middle temporal visual area (MT) and their relationship to a cortical hierarchy in the macaque monkey. J Neurosci. 1983;3:2563–2586. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.03-12-02563.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merker B. Silver staining of cell bodies by means of physical development. J Neurosci Methods. 1983;9:235–241. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(83)90086-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohlberg H, Lerch J, Amunts K, Evans AC, Zilles K. Probabilistic cytoarchitectonic maps transformed into MNI space. Abstract presented at 9th International Conference on Functional Mapping of the Human Brain 2003; 2003. Available on CD-Rom. [Google Scholar]

- Murata A, Gallese V, Kaseda M, Sakata H. Parietal neurons related to memory-guided hand manipulation. J Neurophysiol. 1996;75:2180–2186. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.75.5.2180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata A, Gallese V, Luppino G, Kaseda M, Sakata H. Selectivity for the shape, size, and orientation of objects for grasping in neurons of monkey parietal area AIP. J Neurophysiol. 2000;83:2580–2601. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.5.2580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieder A. The number domain – can we count on parietal cortex? Neuron. 2004;44:407–409. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono M, Kubik S, Abernathey CD. Atlas of the cerebral suci. Stuttgart: Thieme; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Huang Y, Toga A. The Rhesus Monkey Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Academic Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson K. Method of moments and method of maximum likehood. Biometrika. 1936;28:34–59. [Google Scholar]

- Petrides M, Pandya DN. Comparative architectonic analysis of the human and the macaque frontal cortex. In: Boller F, Grafman J, editors. Handbook of Neuropsychology. New York: Elsevier; 1994. pp. 17–58. [Google Scholar]

- Petrides M, Cadoret G, Mackey S. Orofacial somatomotor responses in the macaque monkey homologue of Broca's area. Nature. 2005;435:1235–1238. doi: 10.1038/nature03628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinel P, Le Clec' H, Van de Moortele PF, Naccache L, Le Bihan D, Dehaene S. Event-related fMRI analysis of the cerebral circuit for number comparison. Neuroreport. 1999;10:1473–1479. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199905140-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinel P, Dehaene S, Riviere D, LeBihan D. Modulation of parietal activation by semantic distance in a number comparison task. NeuroImage. 2001;14:1013–1026. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Retzius G. Das Menschenhirn Vol I. Stockholm: Norstedt and Soener; 1896. [Google Scholar]

- Roland PE, Zilles K. Brain atlases--a new research tool. Trends Neurosci. 1994;17:458–467. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(94)90131-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakata H, Taira M, Murata A, Mine S. Neural mechanisms of visual guidance of hand action in the parietal cortex of the monkey. Cereb Cortex. 1995;5:429–438. doi: 10.1093/cercor/5.5.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakata H, Taira M, Kusunoki M, Murata A, Tanaka Y, Tsutsui K. Neural coding of 3D features of objects for hand action in the parietal cortex of the monkey. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1998;353:1363–1373. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1998.0290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleicher A, Zilles K. A quantitative approach to cytoarchitectonics: analysis of structural inhomogeneities in nervous tissue using an image analyser. J Microsc. 1990;157:367–381. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.1990.tb02971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleicher A, Amunts K, Geyer S, Morosan P, Zilles K. Observer-independent method for microstructural parcellation of cerebral cortex: A quantitative approach to cytoarchitectonics. NeuroImage. 1999;9:165–177. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1998.0385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semendeferi K, Armstrong E, Schleicher A, Zilles K, van Hoesen GW. Prefrontal cortex in humans and apes: a comparative study of area 10. Americal Journal of Physical Anthropology. 2001;114:224–241. doi: 10.1002/1096-8644(200103)114:3<224::AID-AJPA1022>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sereno MI, Pitzalis S, Martinez A. Mapping of contralateral space in retinotopic coordinates by a parietal cortical area in humans. Science. 2001;294:1350–1354. doi: 10.1126/science.1063695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherwood CC, Holloway RL, Erwin JM, Schleicher A, Zilles K, Hof PR. Cortical orofacial motor represenation in old world monkeys, great apes, and humans. I. Quantitative analysis of cytoarchitecture. Brain Behav Evol. 2004;63:61–81. doi: 10.1159/000075672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shikata E, Tanaka Y, Nakamura H, Taira M, Sakata H. Selectivity of the parietal visual neurons in 3D orientation of surface of stereoscopic stimuli. Neuroreport. 1996;7:2389–2394. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199610020-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shikata E, Hamzei F, Glauche V, Knab R, Dettmers C, Weiller C, Buchel C. Surface orientation discrimination activates caudal and anterior intraparietal sulcus in humans: an event-related fMRI study. J Neurophysiol. 2001;85:1309–1314. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.3.1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shikata E, Hamzei F, Glauche V, Koch M, Weiller C, Binkofski F, Buchel C. Functional properties and interaction of the anterior and posterior intraparietal areas in humans. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:1105–1110. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon O, Mangin JF, Cohen L, Le Bihan D, Dehaene S. Topographical layout of hand, eye, calculation and language-related areas in the parietal lobe. Neuron. 2002;33:475–487. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00575-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taira M, Mine S, Georgopoulos AP, Murata A, Sakata H. Parietal cortex neurons of the monkey related to the visual guidance of hand movement. Exp Brain Res. 1990;83:29–36. doi: 10.1007/BF00232190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taira M, Kawashima R, Inoue K, Fukuda H. A PET study of axis orientation discrimination. Neuroreport. 1998;9:283–288. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199801260-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taira M, Tsutsui KI, Jiang M, Yara K, Sakata H. Parietal neurons represent surface orientation from the gradient of binocular disparity. J Neurophysiol. 2000;83:3140–3146. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.5.3140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talairach J, Tournoux P. Coplanar stereotaxic atlas of teh human brain. Stuttgart: Thieme; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Ungerleider LG, Desimone R. Cortical connections of visual area MT in the macaque. J Comp Neurol. 1986;248:190–222. doi: 10.1002/cne.902480204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uylings HBM, Eden GCv, Hofman MA. Morphometry of size/volume variables and comparison of their bivariate relations in the nervous system under different conditions. J Neurosci Methods. 1986;18:19–37. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(86)90111-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Economo K, Koskinas G. Die Cytoarchitektonik der Hirnrinde des erwachsenen Menschen. Wien: Springer; 1925. [Google Scholar]

- Wree A, Schleicher A, Zilles K. Estimation of volume fractions in nervous tissue with an image analyzer. J Neurosci Methods. 1982;6:29–43. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(82)90014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilles K, Armstrong E, Schlaug G, Schleicher A. Quantitative cytoarchitectonics of the posterior cingulate cortex in primates. JCompNeurol. 1986;253:514–524. doi: 10.1002/cne.902530408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilles K, Palomero-Gallagher N. Cyto-,myelo-, and receptor architectonics of the human parietal cortex. NeuroImage. 2001;14:S8–S20. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilles K, Schleicher A, Palomero-Gallagher N, Amunts K. Quantitative analysis of cyto- and receptor architecture of the human brain. In: Toga AW, Mazziotta JC, editors. Brain Mapping: The Methods. Academic Press; 2002. pp. 573–602. [Google Scholar]

- Zilles K. Architecture of the human cerebral cortex: Regional and laminar organizaion. In: Paxinos G, Mai J, editors. The Human Nervous System. Amsterdam: Elsevier Academic Press; 2004. pp. 997–1055. [Google Scholar]