Abstract

Background Geographical variation in dementia prevalence and incidence may indicate important socio-environmental contributions to dementia aetiology. However, previous comparisons have been hampered by combining studies with different methodologies. This review systematically collates and synthesizes studies examining geographical variation in the prevalence and incidence of dementia based on comparisons of studies using identical methodologies.

Methods Papers were identified by a comprehensive electronic search of relevant databases, scrutinising the reference sections of identified publications, contacting experts in the field and re-examining papers already known to us. Identified articles were independently reviewed against inclusion/exclusion criteria and considered according to geographical scale. Rural/urban comparisons were meta-analysed.

Results Twelve thousand five hundred and eighty records were reviewed and 51 articles were included. Dementia prevalence and incidence varies at a number of scales from the national down to small areas, including some evidence of an effect of rural living [prevalence odds ratio (OR) = 1.11, 90% confidence interval (CI) 0.79–1.57; incidence OR = 1.20, 90% CI 0.84–1.71]. However, this association of rurality was stronger for Alzheimer disease, particularly when early life rural living was captured (prevalence OR = 2.22, 90% CI 1.19–4.16; incidence OR = 1.64, 90% CI 1.08–2.50).

Conclusions There is evidence of geographical variation in rates of dementia in affluent countries at a variety of geographical scales. Rural living is associated with an increased risk of Alzheimer disease, and there is a suggestion that early life rural living further increases this risk. However, the fact that few studies have been conducted in resource-poor countries limits conclusions.

Keywords: Dementia, Alzheimer disease, epidemiology, geography, disease clustering

Introduction

Tobler’s first law of geography states that the relationship between entities is stronger when they are close than when they are distant.1 In epidemiology, this is equally true for disease occurrence: clustered areas of low or high incidence may implicate environmental exposures associated with the disease, and this may have important public health consequences. Leukaemia demonstrates geographical clustering that may be related to proximity to nuclear facilities.2,3 Similarly, the worldwide variation in multiple sclerosis rates suggests a complex interplay of genetic and environmental factors, such as climate, diet, geomagnetism, toxins and infection.4–6 Clustering in both space7,8 and spacetime9 in schizophrenia has been described. Although systematic reviews of geographical variation in dementia exist,10–12 previous aggregations of the evidence have relied on the ad hoc comparison of dementia occurrence across studies focusing on contrasting geographical locations (e.g. different countries or urban and rural areas).

However, data from a single study in one geographical location cannot be directly compared with those of another single centre study from another location because methodological differences between the studies; for example, differing diagnostic criteria or the way they are operationalized, may produce artefactual differences in prevalence or incidence. Accordingly, we provide an update of this evidence together with meta-analysis examining geographical variation in the prevalence and incidence of dementia from within-study comparisons.

Method

Information sources

We adopted a four-pronged approach to identifying relevant studies. First, we conducted an electronic search of relevant databases. Secondly, we scrutinized the reference sections of identified publications. Thirdly, we contacted experts in the field. Fourthly, we re-examined papers already known to us. Searches were conducted by an information scientist (C.F.). Table 1 shows databases utilized with dates. Comprehensive search criteria were developed iteratively. The full electronic search strategies for all databases used, including limits applied, are reported in the Supplementary Appendix A1. Results of the literature search were independently screened in parallel by two reviewers (T.R. and G.H.). Abstracts of relevant titles were reviewed and the full text of each highlighted article was obtained.

Table 1.

Databases searched and dates of searches

| Database | Database start | Date searched |

|---|---|---|

| ASSIA (Applied Social Science Index) | 1987 | 8 April 2010 |

| Embase | 1974 | 8 April 2010 |

| FRANCIS | 1984 | 8–9 April 2010 |

| GEOBASE | 1980 | 8 April 2010 |

| Global Health | 1973 | 9 April 2010 |

| LILACS | 1982 | 9 April 2010 |

| Medline | 1950 | 8 April 2010 |

| PsycINFO | 1806 | 8 April 2010 |

| CINAHL | 1981 | 8 April 2010 |

| COPAC | 1100 | 14 April 2010 |

| SciELO | 1997 | 14 April 2010 |

| EThOS (British Library Electronic Theses Online Service) | – | 14 April 2010 |

| Australian Digital Theses (ADT) Program | 1998 | 14 April 2010 |

| Index to Theses | – | 14 April 2010 |

| ProQuest Dissertations and Theses | 1861 | 15 April 2010 |

| Theses Canada Portal | 1965 | 15 April 2010 |

| Conference Papers Index | – | 15 April 2010 |

| PapersFirst | 1993 | 15 April 2010 |

| ProceedingsFirst | 1993 | 15 April 2010 |

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria were as follows: cross-sectional and longitudinal studies of any length offering a comparison of dementia prevalence or incidence between two or more different sites, at any geographical scale. Grey literature and theses were included. We did not limit the search by language (as long as there was an English language abstract) with the intention of having relevant papers translated. We also included papers in languages other than English if other reports from the same study had been published in English to allow adequate assessment of the methodology, and this further report contained relevant data. Articles could consider all causes of dementia apart from those secondary to external causes or where dementia is a later secondary feature of the disorder, e.g. alcohol or traumatic brain injury, Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease and Creutzfeld Jakob disease, either sporadic or variant.

Exclusion criteria were as follows: papers comparing studies using external comparison groups, which were conducted independently or which used different methodologies (for example, the European Community Concerted Action on the Epidemiology and Prevention of Dementia/European Collaboration on Dementia papers13–16 or other ‘quantitative integrations of the literature’10), studies with no spatial variable (e.g. comparing different ethnic groups or investigating aluminium or silicate concentrations in water) and references with no abstract and a vague title (e.g. ‘epidemiology of dementia’). Studies focusing purely on young onset dementia were excluded to reduce heterogeneity in the review.

A large number of papers describe the clusters of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/parkinsonism–dementia complex in the Pacific basin. This cluster was included because the condition is prominently characterized by dementia. Due to the wealth of literature describing these isolated clusters, a representative paper was selected for inclusion.

Data collection

The principal summary measure was the prevalence or incidence of dementia in the two (or more) areas studied. Other data collected were the scale of comparison or areas that were compared, methods (including diagnostic criteria) and measures used, details and number of participants, including ages. The studies were also assessed for quality of design and methodology from A (best) to E (worst), including a consideration of bias. This measure of quality took into account quality and limitations of case-finding procedures, diagnostic criteria used, standardization across sites and completeness of follow-up in longitudinal studies.

Estimates of error were not reported by all authors, limiting the precision of comparisons of reported prevalence or incidence rates. Where possible, reported P-values were converted to 95% confidence intervals (CIs).17

Meta-analysis

Numbers of cases and non-cases in the studies comparing prevalence or incidence of dementia in rural and urban areas were used to compute odds ratios (ORs) with accompanying 90% CIs, in line with statistical guidance.18 Urban areas formed the referent in all models. Where raw numbers were not reported, ORs and 95% CIs were converted to log ORs and log variances. These study-specific estimates of prevalence and incidence were meta-analysed, using random-effects models because there was a large amount of heterogeneity (prevalence studies: I2 = 90.8%; incidence studies: I2 = 81.2%). Authors of studies reporting insufficient data19–21 were contacted, apart from Leighton et al.22 for whom contact details were unavailable.

Sensitivity analyses

One prevalence study classified participants according to more than one set of diagnostic criteria.23 In the main analyses, the results using Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth revision (DSM-IV) criteria were used. We also examined the effect of altering the diagnostic criteria used and the effect of excluding the study completely from the models. We conducted a further sensitivity analysis stratifying the prevalence and incidence meta-analyses by study quality.

Statistical analyses were conducted using R version 2.15.024 and the metafor package.25 Figures 3 and 4 were drawn with the R package Rmeta.26 The reporting of this systematic review conforms to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement.27

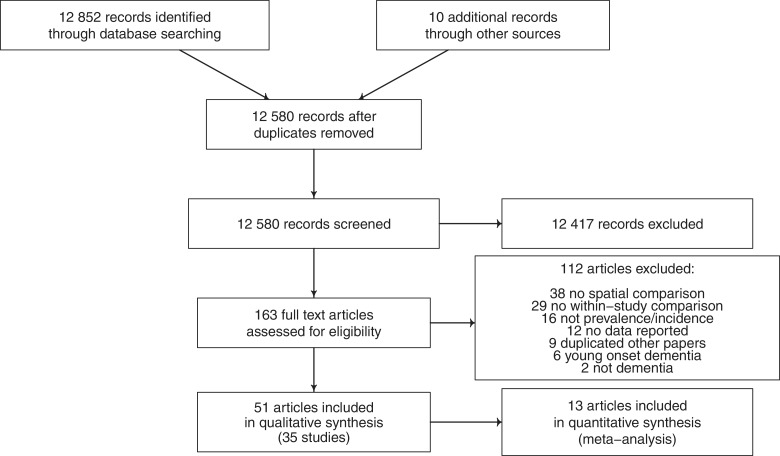

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram showing selection of studies for inclusion in systematic review of geographical clustering of dementia prevalence and incidence

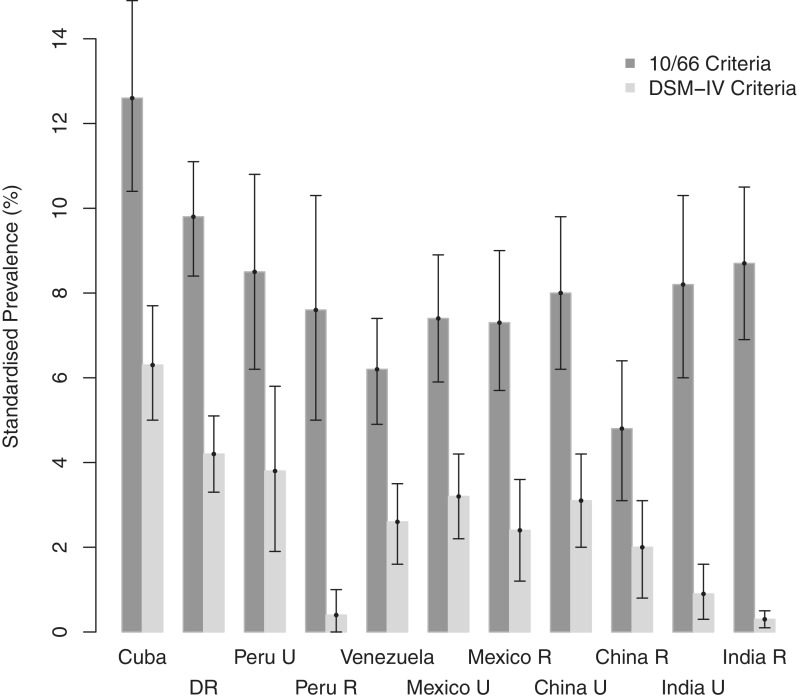

Figure 2.

Comparison of standardized dementia prevalence (95% CI) with different diagnostic criteria. Constructed from 10/66 Dementia Research Group data.23 DR = Dominican Republic, U = urban, R = rural

Results

A total of 12 580 records were screened, and the two reviewers (T.R. and G.H.) produced shortlists of 164 and 173 papers, respectively, that potentially matched inclusion criteria. Of 163 papers examined, 112 studies were excluded (reasons for exclusion are outlined in Figure 3, which shows the screening process), leaving 51 articles (from 35 unique studies), which are summarized in Tables 2–6.

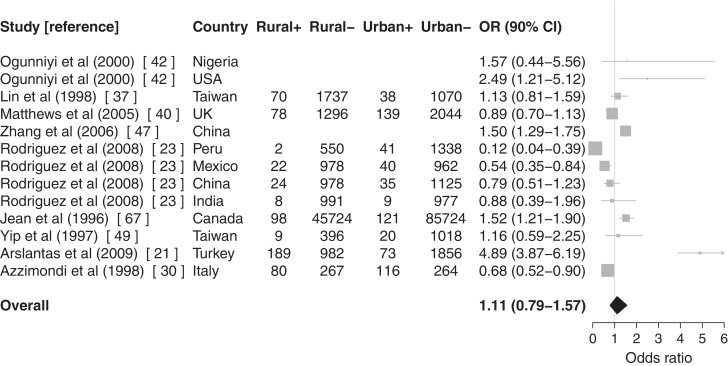

Figure 3.

Meta-analysis with forest plot of urban/rural differences in dementia prevalence (using DSM-IV criteria for Ref. 23). Rural+: dementia cases in rural areas, Rural−: non-dementia cases in rural areas, Urban+: dementia cases in urban areas and Urban−: non-dementia cases in urban areas. Articles without case numbers reported ORs and 95% CIs rather than raw numbers. Urban areas form the referent

Table 2.

Studies meeting inclusion criteria: country–country comparisons or surveys comparing country of birth

| Author | Year | Study | Setting | Methods | Measures | Diagnostic criteria | Participants | Ages (years) | Total number | Cases | Quality (A–E) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anzola-Perez et al. | 1996 | Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) study51 | Argentina, Chile and Cuba | One-phase survey | Spanish MMSE | MMSE score | Age- and sex-stratified random community samples | ≥60 | 3211 | Variable | D: methodologies differ slightly |

| Cristina et al. Román | 1997, 1998 | ‘COLOMBO 2000’ project64,88 | Argentina and Italy | Death certificate data | – | Not stated | All AD deaths | Not defined | 90.8 million | Not stated | E: relies on diagnosis being recorded; population age-structures different |

| Livingston et al. | 2001 | Islington study54 | Islington, London | One-phase survey | Short-CARE interview | Short-CARE | Random sample stratified by country of birth | ≥65 | 1085 | 107 | C: good ascertainment; use of place of birth confounds migration and other factors |

| Figueroa et al. | 2008 | Ref. 60 | USA and Puerto Rico | Death certificate data | – | ICD-10 | All AD deaths | Not defined | Census | Not stated | E: relies on diagnosis being recorded |

| Rodriguez et al., Sousa et al. | 2008, 2009 | 10/66 Dementia Research Group23,57 | Cuba, Dominican Republic, Mexico, Peru, Venezuela, China and India | Cross-sectional comprehensive one-phase surveys | – | 10/66 criteria DSM-IV | All residents in geographically-defined catchment areas | ≥65 | 14 960 | Not stated | B: screening difficulties possible; standardization between so many centres challenging |

| Adelman et al. | 2011 | Ref. 50 | Haringey, London | Two-phase survey | MMSE CAMCOG | ICD-10 DSM-IV-TR Consensus criteria for sub-types | Random sample of General Practitioner (GP) lists stratified by recorded ethnic group | ≥60 | 436 | 36 | C: robust design but spatial variable is confounded by migration |

Table 3.

Studies meeting inclusion criteria: rural/urban comparisons

| Author | Year | Study | Setting | Methods | Measures | Diagnostic criteria | Participants | Ages (years) | Total number | Cases | Quality (A–E) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leighton et al. | 1963 | Ref. 22 | Nigeria: Yoruba villages and Abeokuta town | Population survey | – | Not stated | People with ‘chronic brain syndrome’ | Not defined | 326 | 17 (estimated) | E: unclear |

| Imaizumia | 1992 | Ref. 20 | Japan | Death certificate data | – | ICD-9 | All AD deaths | ≥35 | Total population | 931 | E: relies on diagnosis being recorded |

| Emard et al.a | 1992 | Projet IMAGE66,67,71 | Saguenay-Lac-Saint-Jean territory, Québec, Canada | Case register | Reisberg GDS | Adapted NINCDS-ADRDA | AD cases | Not defined | 131 667 live births | 235 | C: dependent on quality of case register; case ascertainment and representativeness of sample unclear; differential mortality a potential bias |

| Perron et al.a | 1993 | Screening | |||||||||

| Jean et al.a | 1996 | Clinical assessment | |||||||||

| Ebly et al.a | 1994 | Canadian Study of Health and Aging33,34,39 | All ten provinces of Canada | Two-phase screening | 3MS | CSHA NINDS-AIREN DSM-III | Random sample from community and institutionalized residents | ≥65 | 5924 | 97 | B: robust design but ascertainment unclear |

| Manfreda | 1995 | Incidence study (5 years) | Clinical assessment (including all institutionalised individuals) | ||||||||

| Hébert et al.a | 2000 | ||||||||||

| Yip et al. | 1997 | Ref. 49 | Taiwan: Ta-an district (urban) and Chin-shan Hsiang (rural) | Multiphase survey | Chinese MMSE | DSM-III-R | Random sample of community stratified by age | ≥65 | 1443 | 29 | C: relatively robust but different response rates, 90% vs 71% |

| ADL scales | |||||||||||

| Clinical assessment | |||||||||||

| Liu et al. | 1997 | Refs. 38,37 | Southern Taiwan | Two-phase screening Incidence study | Chinese MMSE | ICD-10-NA NINCDS-ADRDA | Random sample stratified by rurality | ≥65 | 2915 | 108 | B: reasonable design |

| Lin et al. | 1998 | Blessed Dementia Rating Scale | |||||||||

| Clinical assessment | |||||||||||

| Azzimondi et al. | 1998 | Ref. 30 | Sicily, Italy: Troina (isolated and rural) and S. Agata Militelo (a more developed small town) | Two-phase screening | Italian MMSE | DSM-III-R | 50% random sample | ≥75 | 693 | 196 | E: no power calculation and no statistical comparisons; clinical assessment only of sample of borderline cases, not all who screened negative |

| Clinical assessment | |||||||||||

| MRC CFASa | 1998 | MRC CFAS31,40,41 | UK: Four urban and two rural areas | Two-phase screening | GMS AGECAT | AGECAT | Stratified random community sample | ≥65 | 13 004 (prevalence) | 214 prevalent 630 incident | B: Robust design; unreported measures; 2-fold variation in prevalence reasonable |

| Matthews et al.a | 2005 | Incidence study (2 years) | MMSE | 7175 (incidence) | |||||||

| Brayne et al.a | 2006 | GMS Assessment CAMCOG | |||||||||

| Hendrie et al.a | 1995 | Ibadan–Indianapolis study36,42 | Ibadan, Nigerian and Indianapolis, USA | Two-phase screening | CSID | DSM-III-R and ICD-10 | Community-dwelling Yoruba or sample of African Americans living in the community or in 6 representative nursing homes | ≥65 | 4706 | 93 | A: robust identical methodologies |

| Ogunniyi et al.a | 2000 | Clinical assessment | |||||||||

| Hendrie et al.a | 2001 | Ibadan1–Indianapolis study35,43 | Ibadan, Nigeria and Indianapolis, USA | Incidence study (2 and 5 years) | CSID | DSM-III-R and ICD-10 | Community-dwelling Yoruba or African Americans | ≥65 | 4606 | 187 | A: robust identical methodologies |

| Ogunniyi et al.a | 2006 | Two-phase screening | Clinical assessment | ||||||||

| Zhang et al.a | 2005 | Refs. 46, 47 | Four regions of China | Two-phase screening | Chinese MMSE | DSM-IV | Stratified, multistage, cluster random sample from census | ≥55 | 34 807 | 1027 | B: thorough case-finding and 80–90% follow-up; crude prevalences reported |

| Zhang et al.a | 2006 | Clinical assessment | ICD-10 | ||||||||

| Re-examination at 6 months | |||||||||||

| Bermejo-Pareja et al.a | 2008 | Neurologic disorders in central Spain19 | Spain: Las Margaritas, greater Madrid (working class), Lista, central Madrid (professional class) and Arévalo (agricultural) | Two-phase screening | Spanish MMSE | Consensus | Census data for geographically defined areas | ≥65 | 5278 (prevalence) | 306 prevalent | A: robust methodology |

| Incidence study (3 years) | Pfeffer activities questionnaire | DSM-IV | 3891 (incidence) | 161 incident | |||||||

| Clinical assessment | |||||||||||

| Rodriguez et al.a | 2008 | 10/66 Dementia Research Group23,57 | Cuba, Dominican Republic, Mexico, Peru, Venezuela, China and India | Cross-sectional comprehensive one-phase surveys | – | 10/66 criteria | All residents in geographically defined catchment areas | ≥65 | 14 960 | Not stated | B: sreening difficulties possible; standardization between so many centres challenging |

| Sousa et al.a | 2009 | DSM-IV | |||||||||

| Arslantas et al. | 2009 | Ref. 21 | Eskisehir city, middle Anatolia, Turkey | Two-phase screening | Turkish MMSE | NINCDS-ADRDA NINDS-AIREN | Random cluster sample of geographically defined areas | ≥55 | 3100 | 262 | D: relatively robust methodology but 49.5% who failed MMSE declined further assessment and no one with MMSE >25 was assessed further |

| Clinical assessment |

aArticles also appear in another table.

NINCDS-ADRDA: National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association; NINDS-AIREN: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and Association Internationale pour la Recherché et l'Enseignement en Neurosciences; ADL: Activities of daily living; GDS: Geriatric Depression Scale.

Table 4.

Studies meeting inclusion criteria: regional comparisons

| Author | Year | Study | Setting | Methods | Measures | Diagnostic criteria | Participants | Ages (years) | Total number | Cases | Quality (A–E) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sulkava et al. | 1985 | Mini-Finland44,45 | Finland | Two-phase screening | Cattel’s G-factor test | DSM-III | Representative sample of Finnish population | ≥30 (≥75 for dementia project) | 8000 | 141 | B: robust design and representative sample. |

| Sulkava et al. | 1988 | Verbal memory test | |||||||||

| Clinical assessment | |||||||||||

| Jorm et al. | 1989 | Ref. 63 | Six Australian states | Death certificate data | – | ICD-9 | All deaths 1979–85 | Not defined | – | – | E: depends on dementia being reported |

| Zhang et al. | 1990 | Guam72 | Guam, Mariana Islands, NW Pacific, 1956–85 | Case register | Direct standardization of incidence rates using 1960 Chamorro population age distribution | Neuropathological and clinical criteria90 | All cases of parkinsonism-dementia complex | Not defined | Not stated | 340 | C: completeness of case register may vary with time and location |

| Imaizumi | 1992 | Ref. 20 | Japan | Death certificate data | – | ICD-9 | All AD deaths | ≥35 | Total population | 931 | E: relies on diagnosis being recorded |

| Canadian Study of Health and Aging Working Group | 1994 | Canadian Study of Health and Aging32,33,39 | Five Canadian provinces | Two-phase screening | 3MS | DSM-III | Random sample from community and institutionalized residents | ≥65 | 10 204 (1809) | 1125 (515) | B: robust design but ascertainment unclear; Ebly et al. (1994) only included over-85s—in brackets33 |

| Ebly et al. | 1994 | Clinical assessment (including all institutionalized individuals) | |||||||||

| Manfreda | 1995 | ||||||||||

| Hébert et al. | 2000 | Canadian Study of Health and Aging34 | All 10 Canadian provinces | Two-phase screening | 3MS | CSHA NINDS-AIREN DSM-III | Random sample from community and institutionalized residents | ≥65 | 5924 | 97 | B: robust design but ascertainment unclear |

| Incidence study (5 years) | Clinical assessment (including all institutionalized individuals) | ||||||||||

| White et al. | 1994 | Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly59 | USA: East Boston, Iowa and New Haven | One-phase survey | Short portable MSQ | SPMSQ ≥3 | Community population | ≥65 | 9174 | 1918 | E: methods unclear, comparability questionable |

| Incidence study (3 and 6 years) | ICD-9 | ||||||||||

| MRC CFAS | 1998 | MRC CFAS31,40,41 | UK: Four urban and two rural areas | Two-phase screening | GMS AGECAT | AGECAT | Stratified random community sample | ≥65 | 13 004 (prevalence) | 214 prevalent 630 incident | B: robust design; unreported measures; 2-fold variation in prevalence reasonable |

| Matthews et al. | 2005 | Incidence study (2 years) | MMSE | 7175 (incidence) | |||||||

| Brayne et al. | 2006 | GMS assessment | |||||||||

| Hendrie et al. | 1993 | Ref. 48 | Canada: Two Cree reserves in Northern Manitoba and Winnipeg | Two-phase screening | Initial interview | DSM-III-R | All registered Cree | ≥65 (over-sampling of ≥80 s in Winnipeg) | 468 | 31 | C: comprehensive Cree register and reasonably comparable population, though institutional sample included; screening sensitive |

| Clinical assessment (culturally adapted) | Winnipeg: age-stratified sample from Health Insurance database | ||||||||||

| Zhang et al. | 2005 | Ref. 46, 47 | Four regions of China | Two-phase screening | Chinese MMSE | DSM-IV | Stratified, multistage, cluster random sample from census | ≥55 | 34 807 | 1027 | B: thorough case-finding and 80–90% follow-up; crude prevalences reported |

| Zhang et al. | 2006 | Clinical assessment | ICD-10 | ||||||||

| Re-examination at 6 months | |||||||||||

| Laditka et al. | 2008 | Refs. 68–70 | South Carolina, USA | Case register | – | ICD-9-CM | AD cases | Not defined | US census | 33 754 (estimated) | B: very robust methodology but unclear when spatial analysis conducted (i.e. birth, adulthood etc.) |

| Laditka et al. | 2006 | ||||||||||

| Laditka et al. | 2006 | ||||||||||

| Figueroa et al. | 2008 | Ref. 60 | USA and Puerto Rico | Death certificate data | – | ICD-10 | All AD deaths | Not defined | Census | Not stated | E: relies on diagnosis being recorded |

| Bermejo-Pareja et al. | 2008 | Neurologic Disorders in Central Spain19 | Spain: Las Margaritas, greater Madrid (working class), Lista, central Madrid (professional class) and Arévalo (agricultural) | Two-phase screening | Spanish MMSE | DSM-IV | Census data for geographically defined areas | ≥65 | 5728 (prevalence) | 306 prevalent | A: robust methodology |

| Incidence study (3 years) | Pfeffer activities questionnaire | 3891 (incidence) | 161 incident | ||||||||

| Clinical assessment | |||||||||||

| Steenland et al. | 2009 | Ref. 29 | USA 1999–2004 | Death certificate data | – | ICD-10 | All AD deaths | Not defined | 1.7 billion | 336 232 | E: relies on diagnosis being recorded |

| Gillum et al. | 2011 | Ref. 65 | USA | Death certificate data | – | ICD-10 | All AD deaths 1999/2000 and 2005/06 | Not defined | Not stated | 555 904 dementia | E: relies on diagnosis being recorded |

| 211 386 AD (both 2005/06) |

Table 5.

Studies meeting inclusion criteria: town/city comparisons

| Author | Year | Study | Setting | Methods | Measures | Diagnostic criteria | Participants | Ages (years) | Total number | Cases | Quality (A–E) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gurland et al. | 1979 | US–UK Geriatric Community Study28 | New York and London | One-phase survey | MSQ | MSQ ≥8 | Random sample of elderly in institutions | Not defined | 321 | 117 (estimated) | C: reasonable methodology; small study |

| CARE interview (modified) | |||||||||||

| Ichinowatari et al. | 1987 | Ref. 53 | Japan: Sashiki village and Ikema Island, Okinawa | One-phase survey | Not stated | ICD-9 | Over 65s clinically diagnosed with dementia | ≥65 | 919 | 45 | A: clinical assessment of entire populations |

| One year of follow-up for confirmation | |||||||||||

| Copeland et al. | 1987 | US-UK Cross-National (Diagnostic) Project52 | New York and London | One-phase survey | GMS AGECAT | AGECAT | New York: random cluster sample | ≥65 | 841 | – | C: validity depends on AGECAT; DSM-III diagnosis confirms AGECAT diagnosis in London sample |

| DSM-III (London only) | London: random sample from 3000 GPs | ||||||||||

| Lobo | 1990 | Refs. 55, 56 | Zaragoza, Spain and Liverpool, UK | One-phase survey | GMS AGECAT | AGECAT | Random age-stratified sample from census (Spain) or GP lists (UK) | ≥65 | 2150 | 134 | D: unclear if comparison is an a priori hypothesis; random sampling subverted in Spain |

| Lobo et al. | 1992 | ||||||||||

| Hendrie et al. | 1995 | Ibadan–Indianapolis study36,42 | Ibadan, Nigeria and Indianapolis, USA | Two-phase screening | CSID | DSM-III-R and ICD-10 | Community-dwelling Yoruba (total population survey of geographically-defined area) or African Americans living in the community (60% sample) or in six representative nursing homes | ≥65 | 4706 | 93 | A: robust identical methodologies |

| Ogunniyi et al. | 2000 | Clinical assessment | |||||||||

| Hendrie et al. | 2001 | Ibadan–Indianapolis Study35,43 | Ibadan, Nigeria and Indianapolis, USA | Incidence study (2 and 5 years) | CSID | DSM-III-R and ICD-10 | Community-dwelling Yoruba or African Americans | ≥65 | 4606 | 187 | A: robust identical methodologies |

| Ogunniyi et al. | 2006 | Two-phase screening | Clinical assessment | ||||||||

| Artero et al. | 2003 | 3C Study58 | France: Bordeaux, Dijon and Montpellier | One-phase survey | Cognitive battery | DSM-IV | Random sample of non-institutionalized over 65s | ≥65 | 9294 | 637 (estimated) | C: reasonable methodology; in Dijon, screening estimated to be 87.5% sensitive and 78.8% specific |

| Incidence study (2 and 4 years) | Clinical assessment (sample in Dijon) |

Table 6.

Studies meeting inclusion criteria: small area comparisons

| Author | Year | Study | Setting | Methods | Measures | Diagnostic criteria | Participants | Ages (years) | Total number | Cases | Quality (A–E) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frecker | 1991 | Ref. 61 | Newfoundland, Canada | Death certificate data and case note scrutiny | – | Not stated | All deaths mentioning dementia 1985–1986 | Not defined | 7238 | 399 | C: relies on diagnosis being recorded or sufficient information in case notes; very robust otherwise including controls for sex and survival biases |

| Emard et al. | 1992 | Projet IMAGE66,67,71 | Saguenay-Lac- Saint-Jean territory, Québec, Canada | Case register | Reisberg GDS | Adapted NINCDS- ADRDA | AD cases | Not defined | 131 667 live births | 235 | C: dependent on quality of case register; case ascertainment and representativeness of sample unclear; differential mortality a potential bias |

| Perron et al. | 1993 | Screening | |||||||||

| Jean et al. | 1996 | Clinical assessment | |||||||||

| Huss et al. | 2009 | Ref. 62 | Switzerland | Death certificate data linked to census | – | ICD-10 | Community dwellers | ≥30 | 4.65 million | 37 516 | D: relies on diagnosis being recorded |

The studies included were conducted across the world, though predominantly in high-income countries (Europe, Canada and the USA). The studies ranged in size from 32128 to the entire population of the USA.29 Methodologies included multiple-phase population surveys (n = 1319,21,30–50), one-phase surveys (n = 1022,23,28,51–59), using death certificate data (n = 820,29,49,60–65,88) and case registers (n = 366–72). Eight studies included a longitudinal design allowing dementia incidence to be ascertained.19,31,34–35,38–41,43,58,59

Diagnostic criteria used included the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), 9th revision73 (n = 520,53,59,63,68–70) or ICD-1074 (n = 829,35–37,38,42,43,46,47,50,60,62,65), DSM-III75 or DSM-III-R76 (n = 830,32–36,39,42–45,48,49,52) or DSM-IV77 (n = 519,23,46,47,50,57,58). Three studies did not state the diagnostic criteria they used.22,61,64,88 Tests used included the Mini-Mental State Examination78 (MMSE) in various languages (n = 919,21,30,31,37,38,40,41,46,47,49–51), the modified MMSE79,80 (3MS; the Canadian Study of Health & Aging32–34,39), the Community Screening Instrument for Dementia81 (CSID; the Ibadan–Indianapolis study35,36,42,43), the cognitive part of the Cambridge Examination for Mental Disorders of the Elderly82 (CAMCOG; n = 231,40,41,50), the Comprehensive Assessment and Referral Evaluation (CARE) or short-CARE interview83 (n = 228,54) and the Mental Status Questionnaire84 (MSQ) or Short Portable MSQ85 (n = 228,59). Three studies31,40,41,52,55,56 used the Geriatric Mental Schedule (GMS) and the Automated Geriatric Examination for Computer Assisted Taxonomy86,87 (AGECAT). Thirteen studies included a clinical assessment of participants.19,21,30,32–39,42–49,50,58,66,67,71

The papers included in the review were divided into groups reflecting the scale of comparison. Each group will be considered, in turn, comparing rates between countries or nationwide surveys, rural and urban areas, regions, towns or cities and smaller areas.

Country-by-country comparisons or nationwide surveys

Table 2 summarizes the results of the studies identified which compared rates of dementia between countries. There were two main methodologies used at this scale: comparing mortality rates (of the whole population or a sample) between two or more countries and identifying the country of birth of individuals in a discrete area in a single country.

Age-adjusted Alzheimer disease (AD) mortality in 1999 was reported as 15.9% in the USA compared with 21.2% in Puerto Rico.60 Rates for 2004 were 20.9 and 32.4%, respectively. They conjectured that the increase in dementia rates might be explained by improved survival.

The ‘Colombo 2000’ project found disease-specific mortality rates for AD to be higher in Italy (9.8/10 000) than in Argentina (3.4/10 000), which has a large Italian immigrant population.64,88 Another study comparing random samples of the over 60s found that the proportion scoring less than 20 out of 30 on the MMSE was 4.5% in Argentina, 9.4% in Chile and 7.2% in Cuba.51 With a higher cut-off of 22 or less out of 30, the proportions were 8.4% in Argentina, 19.7% in Chile and 16% in Cuba.

The 10/66 Dementia Research Group focuses particularly on the under-researched (and therefore resource-poor) areas of the world.23,57 The authors found a much lower prevalence of dementia by DSM-IV than by 10/66 consensus criteria in India (rural and urban) and Peru (rural only) (Figure 2). Dementia prevalence was found to vary between countries, although the directly standardized prevalence rates differed with the diagnostic criteria used; compared with other sites, prevalence of dementia was higher in Cuba (10/66 criteria: 12.6%, 95% CI 10.4–14.9; DSM-IV: 6.3%, 95% CI 5.0–7.7) and the Dominican Republic (10/66 criteria: 9.8%, 95% CI 8.1–11.1; DSM-IV: 4.2%, 95% CI 3.3–5.1) and lower in rural China (10/66 criteria: 4.8%, 95% CI 3.1–6.4), rural Peru (DSM-IV: 0.4%, 95% CI 0.0–1.0) and both rural (DSM-IV: 0.3%, 95% CI 0.1–0.5) and urban (DSM-IV: 0.9%, 95% CI 0.3–1.6) India.

The remaining studies used the second methodology mentioned earlier—identifying the country of birth of individuals in a single area, thus providing insight into the effect of place of birth on the risk of developing dementia. The Islington study interviewed house to house and grouped the over 65s by country of birth.54 They found no relation between migration per se and dementia. However, the relative risk (RR) for developing dementia did vary by place of birth, being lower in the Irish population (RR: 0.36, 95% CI 0.15–0.87) and higher in the case of people born in Africa or the Caribbean (RR: 1.72, 95% CI 1.06–2.81) when compared with British-born residents. Another London-based study found a higher dementia prevalence in African–Caribbean-born residents of Haringey compared with the White UK-born population (OR = 3.07, 95% CI 1.28–7.32).50

Rural/urban comparisons

Table 3 outlines publications comparing rates of dementia in rural and urban areas. The rural/urban comparisons were quantitatively examined by meta-analysis where possible with the remaining studies being summarized narratively.

Papers that reported (or provided) sufficient prevalence21,23,30,37,40,42,47,49,67 or incidence19,34,40,43 data were meta-analysed using random-effects models, and results are shown in Figures 3 and 4, respectively. Urban areas form the reference group throughout. Out of the authors contacted, two replied providing data for inclusion in the meta-analysis.19,21 Two articles were excluded due to reporting insufficient data.20,22 The latest report from the 10/66 Dementia Research Group was excluded because it did not give sufficient data for inclusion despite reporting a slightly later stage of the study.57

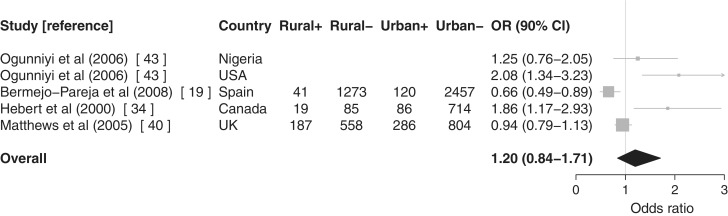

Figure 4.

Meta-analysis with forest plot of urban/rural differences in dementia incidence. Rural+: dementia cases in rural areas, Rural−: non-dementia cases in rural areas, Urban+: dementia cases in urban areas and Urban−: non-dementia cases in urban areas. Articles without case numbers reported ORs and 95% CIs rather than raw numbers. Urban areas form the referent

There was evidence of an association between rurality and prevalence of AD37,42,47,67 (OR = 1.50, 90% CI 1.33–1.69) but much less so for vascular dementia30,37,47 (OR = 1.09, 90% CI 0.65–1.83). Evidence was weaker for an association between rurality and non-specific dementia prevalence21,23,30,37,40,49 (OR = 0.91, 90% CI 0.57–1.45). Pooling all prevalence studies regardless of diagnostic subtype21,23,30,37,40,42,47,49,67 resulted in an intermediate risk of dementia (OR = 1.11, 90% CI 0.79–1.57).

Only one prevalence study classified participants according to more than one set of diagnostic criteria.23 Altering the criteria used had a substantial effect on the association between non-specific dementia and rurality: using DSM-IV criteria (OR = 0.91, 90% CI 0.57–1.45), using 10/66 consensus criteria (OR = 1.14, 90% CI 0.80–1.61) and excluding the four comparisons reported in this study (OR = 1.32, 90% CI 0.73–2.39). Combining all prevalence studies regardless of diagnostic subtype showed a similar pattern: DSM-IV (OR = 1.11, 90% CI 0.79–1.57); 10/66 criteria (OR = 1.26, 90% CI 0.97–1.65); and excluding the study (OR = 1.46, 90% CI 1.02–2.09).

Stratifying prevalence studies by quality reduced the association between rurality and dementia (studies rated D or better:21,23,37,40,42,47,49,67 OR = 1.16, 90% CI 0.80–1.68, C or better:23,37,40,42,47,49,67 OR = 1.03, 90% CI 0.80–1.32 and B or better:23,37,40,42,47 OR = 0.95, 90% CI 0.69–1.29) apart from the two comparisons from the one study rated A for quality,42 which captured early life rural living in which there was an increased association between rurality and AD (OR = 2.22, 90% CI 1.19–4.16).

There was evidence of an association between rurality and dementia incidence19,34,40,43 (OR = 1.20, 90% CI 0.84–1.71), stronger for AD43 (OR = 1.64, 90% CI 1.08–2.50) than for non-specific dementia19,40 (OR = 0.81, 90% CI 0.61–1.09). Restricting the meta-analysis to incidence studies rated A for quality19,43 (no incidence study was rated lower than B) had little effect on the association with rurality (OR = 1.17, 90% CI 0.66–2.06).

There was no evidence of publication bias on formal testing (regression test for funnel plot asymmetry: prevalence studies z = −1.34, P = 0.18; incidence studies z = 1.51, P = 0.13).19,43

Among the studies reporting insufficient data for meta-analysis, a study examining all Japanese death certificates from 1979 to 1990 found that the AD mortality was similar for rural and urban areas,20 and a study in Nigeria found that prevalence of ‘chronic brain syndrome’ did not vary between Yoruba villages and a nearby town in men (6%) but did in women (5% vs 9%).22

Regional comparisons

‘Region’ here refers to an area within a country larger than a town or city. Table 4 summarizes the results of studies identified, which compared rates of dementia between regions.

The Canadian Study of Health & Aging reported a similar prevalence of dementia across Canada but suggested that the relative prevalence of dementia subtypes varied across regions.32–34 Particularly low prevalence of dementia in Ontario men was explained by discrepancies in the use of diagnostic criteria.32 Another Canadian study concluded that dementia prevalence varies little across regions.39 They did note differences between community and institutional samples and noted that dementia prevalence was higher in areas of lower socio-economic status. In rural Manitoba, Canada, the prevalence of dementia among the Cree was found to be the same as a non-native sample in Winnipeg, but there was just one case of AD identified in the Cree (0.5%) compared with 20 in the Winnipeg sample (8.3%; age-adjusted rate: 3.5%, 95% CI 2.1–4.8; P < 0.001).48

A comparison of all dementia deaths in 1999/2000 and 2005/06 across the USA at the county level showed a pattern of marked variation in dementia and AD mortality different to that of cardiovascular disease and stroke.65 Three ‘co-operative longitudinal studies’ in the USA reported 6-year incidence rates of 29.8% in East Boston, 25.0% in New Haven and 20.4% in Iowa.59 Using stricter criteria reduced the variation between sites (East Boston 15.4%, New Haven 14.3% and Iowa 11.3%). Prevalence of AD in South Carolina showed ‘notable variation’ at a county level.68–70 However, it was unclear whether the location was where the individual was born or where they were lived as an adult. Clustering of AD deaths in the north-west and south-east of the USA, with a 4-fold difference in rates between the highest and lowest was identified over the period of 1999–2004.29 A study in Puerto Rico noted variation in mortality rates with dementia in the eight regions of the island.60

The amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/parkinsonism–dementia complex clusters in the Chamorro population of Guam (one of the Mariana Islands in the western Pacific Ocean) and elsewhere have been extensively studied.89 A representative study on Guam identified an incidence gradient, with higher prevalence in southern and central Guam and lower prevalence in northern and western Guam.72,90 More recent reports have not focused directly on the geographical spread of cases.91 There have been suggestions that this cluster could be related to the consumption of a palm, Cycas micronesica, but this has not been definitively proven.92 Similar clusters have been described on the Kii peninsula of Japan—with prevalence in two villages approximately one hundred times that in the rest of the country93—and in West New Guinea.94

Examination of Australian death certificates revealed a much higher prevalence of dementia at death in Tasmania and ‘senility’ in South Australia than the rest of the country.63 Dementia prevalence at death was predominantly related to place of death, but those who were born and died in Tasmania had the highest rate of all. In Tasmania, 43% of dementia death certificates were linked to a single practitioner.

A Japanese study found that AD mortality varied across the country, with Miyazaki prefecture approximately double and Okinawa approximately half the overall national rate.20 Across four areas of China, a north–south gradient in dementia prevalence, particularly for vascular dementia, and a less pronounced east–west gradient were identified.46,47

The Medical Research Council Cognitive Function and Ageing study concluded that there was no evidence of variation in incidence or prevalence of dementia in England and Wales.31,40,41 The incidence of dementia in a working class urban area of Spain was double that in both the agricultural and professional class urban areas.19 A Finnish study found a higher prevalence of AD in the north and east of the country than elsewhere.44,45

Town/city comparisons

Table 5 outlines the articles comparing rates of dementia between towns and cities.

The Ibadan–Indianapolis study identified a higher age-adjusted prevalence of dementia in Indianapolis, USA (4.82%) compared with Ibadan, Nigeria (2.29%; AD: 3.69% vs 1.41%).36,42 At follow-up, age-standardized annual dementia incidence rates were higher in Indianapolis (3.24%, 95% CI 2.11–4.38; Ibadan: 1.35%, 95% CI 1.13–1.56), as were age-standardized annual AD incidence rates (Indianapolis: 2.52%, 95% CI 1.40–3.64; Ibadan: 1.15%, 95% CI 0.96–1.35).35,43

The rates of dementia in the institutionalized elderly population with moderate or severe dementia in New York and London were found to be similar.28 A later study found that rates of organic illness were higher in New York for both men (5.7%; London 2.2%) and women (10.1%; London 5.4%).52

In Okinawa, there was some evidence of variation in rates of dementia between Sashiki village and Ikema island, but these were not formally compared and used as an idiosyncratic case classification.53

No difference in dementia prevalence was found between Zaragoza, Spain and Liverpool.55,56 Furthermore, they identified no sex or age differences. The 3C study found no differences in the distribution of cognitive test scores in three cities across France.58

Small area comparisons

Large-scale (or small area) comparisons are potentially the most informative with regard to identifying socio-environmental risk factors for dementia. Table 6 outlines the papers making such comparisons.

Death certificates for the over 70s were examined in Newfoundland, Canada and two areas had substantially higher dementia mortality rates.61 An excess of individuals born on the north shore of Bonavista Bay dying from dementia were identified (14.3%; south shore: 2.9%). This was not related to differential survival or sex distribution but may have been affected by kinship and migration. Projet IMAGE found no real variation in standardized prevalence rates of dementia in an area of Québec, Canada, despite a trend in two areas.66,67,71 A Swiss study identified a dose–response relationship between the length of time living within 50 m of a power line and developing AD.62

Discussion

Main findings

All published studies indicate that the prevalence and, in one case, incidence of dementia varied between countries, but the precision of estimates was not always clear. Comparing rural and urban areas, there was evidence for an association between rurality and prevalence and incidence of AD. The association with AD prevalence was increased in studies that captured early life rural living. There was less evidence for an association with prevalence or incidence of a general category of dementia. At a regional level, the findings were mixed with some,31–34,40,41 but not all,19 of the better quality studies suggesting that there is little evidence of variation in dementia prevalence or incidence. However, very few studies report data supporting their findings, limiting the certainty of conclusions.

There were fewer large-scale studies and therefore conclusions must be tentative. However, the best quality studies did find variation in dementia incidence between towns/cities.35,36,42,43 The 3C study58 did not but reported the distribution of cognitive test scores rather than actual diagnoses of dementia. At the most informative (i.e. largest) scale, there were fewest studies. However, all except for Projet IMAGE66,67,71 found evidence of variation in dementia prevalence. There were no studies of dementia incidence at this scale.

To summarize, there is evidence, at all scales, of geographical variation in the prevalence or incidence of dementia and, specifically, a higher risk of AD in rural areas. At first glance, the different patterns seen at different scales seem contradictory and confusing. However, this is a common finding with geographical data, the modifiable areal unit problem where, ‘if the spatial units in a particular study were specified differently, we might observe very different patterns and relationships’.95 Unfortunately, none of the included studies collected their data or conducted their analyses at more than one scale, which might shed some light on this ubiquitous problem of spatial data.

The definition of rurality

There was substantial heterogeneity in the studies comparing rural and urban areas. This is likely to be due, at least in part, to the notoriously difficult definition of ‘rurality’. A Japanese study defined an administrative unit as ‘rural’ if the population numbered 30 000 or fewer.20 In Sicily, the isolation of rural Troina (where the ‘economy is almost completely based on farming and grazing’) is contrasted with the urban area ‘connected by rail, sea, a regional road, and a motorway … [where] the economy is more diversified’.30 The 10/66 Dementia Research Group defined rural areas ‘by low population density, and traditional agrarian lifestyle’.96 Projet IMAGE defined a rural area as containing villages rather than cities.97,98 Nevertheless, it is surprising how many studies do not explicitly define rurality—e.g. neither Liu et al.38 nor investigators in the Canadian Study of Health and Aging32,34,99 provided a definition of rurality. This is easier to understand when comparing extremes, for example a large city and distant villages, when the difference is obvious. However, it becomes more difficult to make subtle distinctions. Indeed, a perfect definition may remain elusive, and the epidemiological importance may not lie in the contrast but, rather, in the optimum population density (as has been demonstrated for cardiovascular disease and stroke in men100) and access to health services and factors conducive to a healthy lifestyle.

Young onset dementia

Although studies purely examining young onset dementia were excluded from this review, there are a number of relevant studies that echo the findings in late onset dementia. A study in Israel—using country of birth as the spatial variable—found age- and sex-adjusted incidence rates for European–American-born individuals to be double that of African–Asian-born people.101 At a larger scale, a study in Edinburgh identified all 55 unrelated cases of young onset AD admitted to hospital and noted high prevalence in two geographical areas.102 A subsequent study of young onset dementia across the whole of Scotland looked at the geographical distribution of cases and found non-random distribution of cases of young onset AD but not vascular dementia.103–106 This pattern was partly, but not entirely, explained by kinship, suggesting that socio-environmental factors may also play a role in the aetiology of young onset dementia.104

Limitations of the review and risk of bias within and across studies

The methodology of this review was systematic and robust and the wide, professionally conducted search, and two independent reviewers are likely to have identified all the available literature.

There is the possibility that variation in dementia prevalence or incidence might be the result of chance, but this review includes a large number of studies, many of them methodologically robust, which have found variation, suggesting that chance is unlikely to be behind all of them. Furthermore, all the studies included in the review offer within-study comparisons minimizing the possibility that identified variations in prevalence or incidence are the result of methodological differences between studies.

The first and most profound limitation to and source of bias in this review is the lack of attention paid to epidemiological studies of dementia in large areas of the world,107 a point noted and beginning to be remedied by bodies such as the 10/66 Dementia Research Group,23,57 also recently highlighted in relation to studies in Eastern and Middle European countries.16 This is particularly important because it is predicted that increases in dementia prevalence will be larger in the developing world than elsewhere.107,108 Until there are good quality epidemiological studies across the world, no conclusions regarding the global variation of dementia can be any less than conjectural.

There are significant methodological difficulties involved when comparing epidemiological studies, such as the method and thoroughness of case finding,10 whether the entire population or a sample will be studied109 and the choice of study setting itself. These difficulties are compounded in studies of dementia by consideration of different diagnostic criteria and whether to include mild cases,10 let alone individuals with ‘mild cognitive impairment’. Further biases, such as differential survival and consequent differing age structures of populations, variation in diagnosis rates and reporting of dementia,63,110 screening non-participation and validation,111 access to health care and levels of health and education make conducting and interpreting such studies—even when they are methodologically identical—extremely difficult.11 These challenges are likely to have produced some bias in the studies and are reflected in the variation in quality ratings for the studies. One interesting finding from two studies51,59 is that geographical variation reduces with stricter diagnostic criteria, confirming Jorm’s assertion that the inclusion or exclusion of milder cases can have an important effect on the findings of quantitative studies of dementia.10

Considering diagnostic criteria in more detail, no studies investigated definitive neuropathological diagnoses, and therefore, differential rates of dementia subtypes must be considered no more certain than ‘probable’, in line with diagnostic criteria.112–116 Therefore, the possibility remains that the clinical diagnoses reported in these studies may not perfectly reflect neuropathology, as has been shown previously.117,118 The common neuropathological finding of mixed pathologies further complicates matters. This suggests that conclusions regarding specific dementia subtypes should be considered tentative.

A large number of studies rely on case registers or death certificate data. These methodologies are highly susceptible to bias in that the diagnosis has to be correctly made, recorded and transcribed into the appropriate record. Estimated rates of accurate dementia reporting on death certificates are 25–58%,110,119 but more recent studies suggest that this is improving, for example, in a cohort of 502 deceased individuals with probable AD, 359 (71.5%) had dementia correctly recorded as a cause of death.120 Furthermore, there is a potential spatial confounder in that clinical service provision or quality may vary with geography, resulting in variation of dementia prevalence as in one study where 43% of the cases in a cluster could be linked back to just one clinician, who presumably had a particular interest in dementia.63

Screening studies are more robust, particularly two-stage screening designs and especially when the whole population is screened rather than a sample. However, there is still a danger of selection bias creeping in.111 The best quality studies included were the Neurologic Disorders in Central Spain Study19 and, despite numerous methodological challenges—including estimating the ages of some of the Yoruba interviewed—the Ibadan–Indianapolis study.35,36,42,43 Both studies showed variation in dementia incidence and the latter showed variation in AD prevalence.

The cultural validity of the tests and the rating scales, even if translated, is often unclear. Furthermore, cultural factors related to ageing and functional decline are also highly relevant to variation and a source of bias. Different cultures react to and accommodate ageing in different ways and will treat symptoms of cognitive and functional decline differently. We must not ignore the implicit value-laden nature of many, if not all, diagnoses,121 even dementia—for example, what level of functioning can be expected at what age—and the variation of these values in different countries and different cultures. In fact, from a global perspective, the individual with dementia may not be a fixed kind of person but what Hacking describes as a ‘moving target’.122

Further potential confounders include differential survival or migration—for example, if individuals at a higher risk of developing dementia in an area die or move away, those remaining will have an artefactually low prevalence of dementia. Both migration61 and differential survival35,36,42,43,61 were considered by a small number of the studies. The methodology most susceptible to bias by migration is comparing country of birth of individuals living in a discrete geographical area. The finding that risk of dementia is increased in people born in Africa or the Caribbean50,54 is not matched by increased rates of dementia in these countries that suggests migration may have confounded the studies using this methodology. Similarly, genetic relatedness is a factor that must be taken into account and was estimated by some of the studies included.61,103,104,123

The spatial variable must also be recorded from a sufficiently early point in life to avoid reverse causality, for example mapping the location of death of people with dementia may merely identify the locations of care homes or hospitals with long-stay beds.110

The relative dearth of larger scale comparisons—for example regions, towns or postal districts—limits the precise assessment of any variation that might be found and thus the conclusions that can be drawn about possible socio-environmental exposures.

This review explicitly excluded papers comparing studies conducted independently or with different methodologies. Therefore, there are potentially further studies looking at rates of dementia in rural areas, but the methodological difficulties in combining these with separate studies preclude such a comparison. This criterion is unlikely to have introduced substantial bias but clearly reduces the data available substantially with a consequent impact on CIs for effect estimates.

Implications

Apart from implications for health service provision, the real interest in identifying variation in the prevalence and incidence of a disease is in identifying potentially modifiable risk factors. Many socio-environmental risk factors are likely to have their effect on dementia risk early in life,124–126 though not all studies confirm this association.127 Some of the studies included in the current review examined early life effects, for example place of birth61 or living in a rural area in childhood,42,43 but the majority measured their exposures at the time of the study. The rural/urban meta-analysis suggested that, although rural living may be associated with increased rates of AD, early life rural living may have an even greater effect. There are two possible implications of this finding: that exposure in early life has a greater effect or that duration of exposure determines the risk. Further research is required to clarify this finding.

However, any consideration of geographical variation of dementia must also include geographical variation of related conditions and risk factors. Cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases have been shown to vary in incidence across Scotland, and this variation is partly related to smoking (in both sexes), population density, deprivation, blood pressure and body mass index (in men).100 Temporal trends are also important. The possibility that changes in dementia incidence over time, and some geographical variation, might be related to improved survival following stroke has been raised.128,129 Detailed examination of secular trends in dementia, related conditions and risk factors is required.130

Given the early effects of some risk factors and the presence of pathological changes of AD decades before the clinical onset of dementia,131 any attempts at prevention will need to begin sufficiently early in life. A number of systematic reviews have shown that modifying risk factors in late life, for example lowering blood pressure132 or treatment with statins,133 are ineffective in preventing dementia, consistent with the evidence that many risk factors for dementia have their effects in mid-life or earlier.134–137

This need for sufficiently early intervention is reflected in the ideal methodology of dementia epidemiology studies and the importance of measuring risk factors—including location—at the most appropriate time point. Identification of any putative risk factors, at any geographical scale, requires their measurement to be at a sufficiently early stage for the findings to be clinically meaningful.

Conclusions

Though the extant evidence is far from consistent and varies in quality, prevalence and incidence of dementia do vary, at a number of scales and between countries, regions, towns and cities and small areas. There is weak evidence for variation in dementia incidence or prevalence between rural and urban areas but stronger evidence for AD. Furthermore, early exposure to rural living may have an increased effect on the association between rurality and AD.

Further work to provide higher quality evidence of geographical and temporal variation is required, and comparisons could usefully be made with the geographical distributions of related conditions, such as stroke and cardiovascular disease. The next question is whether the causes of this observed variation can be identified, and, if so, could they highlight modifiable socio-environmental risk factors, thus making dementia a preventable disease?

Supplementary Data

Supplementary Data are available at IJE online.

Funding

T.C.R. is supported by Alzheimer Scotland and employed in the UK National Health Service (NHS) by the Scottish Dementia Clinical Research Network, which is funded by the Chief Scientist Office (part of the Scottish Government Health Directorates). T.C.R. and J.M.S. are members of the Alzheimer Scotland Dementia Research Centre funded by Alzheimer Scotland. T.C.R., J.M.S. and G.D.B. are members of the University of Edinburgh Centre for Cognitive Ageing and Cognitive Epidemiology, part of the cross-council Lifelong Health and Wellbeing Initiative (G0700704/84698). Funding from the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, Economic and Social Research Council and Medical Research Council (MRC) is gratefully acknowledged. G.D.B. is a Wellcome Trust Fellow. During the preparation of this manuscript, G.H. was employed by NHS Fife and, latterly, NHS Lothian. C.F. is employed by the MRC Social and Public Health Sciences Unit.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Benito-León and Professor Özbabalık for providing additional data for the meta-analysis.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

KEY MESSAGES.

Identifying geographical variation in dementia prevalence and incidence could lead to the identification of potentially modifiable risk—or protective—factors.

This review identifies evidence, based on within-study comparisons, at a variety of scales of geographical variation of dementia.

Furthermore, there is evidence from meta-analysis of an association between rural living and AD, particularly for early life rural living.

References

- 1.Tobler W. A computer movie simulating urban growth in the Detroit region. Econ Geogr. 1970;46:234–40. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoffmann W, Terschueren C, Richardson DB. Childhood leukemia in the vicinity of the Geesthacht nuclear establishments near Hamburg, Germany. Environ Health Persp. 2007;115:947–52. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laurier D, Jacob S, Bernier MO, et al. Epidemiological studies of leukaemia in children and young adults around nuclear facilities: a critical review. Radiat Prot Dosim. 2008;132:182–90. doi: 10.1093/rpd/ncn262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosati G. The prevalence of multiple sclerosis in the world: an update. Neurol Sci. 2001;22:117–39. doi: 10.1007/s100720170011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ebers GC, Sadovnick AD. The geographic distribution of multiple sclerosis—a review. Neuroepidemiology. 1993;12:1–5. doi: 10.1159/000110293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Compston A. Genetic epidemiology of multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1997;62:553–61. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.62.6.553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewis G, David A, Andréassson S, Allebeck P. Schizophrenia and city life. Lancet. 1992;340:137–40. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)93213-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mortensen PB, Pedersen CB, Westergaard T, et al. Effects of family history and place and season of birth on the risk of schizophrenia. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:603–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199902253400803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clair DS, Xu M, Wang P, et al. Rates of adult schizophrenia following prenatal exposure to the Chinese famine of 1959-1961. JAMA. 2005;294:557–62. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.5.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jorm AF, Korten AE, Henderson AS. The prevalence of dementia: a quantitative integration of the literature. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1987;76:465–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1987.tb02906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ineichen B. The epidemiology of dementia in Africa: a review. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50:1673–77. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00392-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fratiglioni L, De Ronchi D, Aguero-Torres H. Worldwide prevalence and incidence of dementia. Drugs Aging. 1999;15:365–75. doi: 10.2165/00002512-199915050-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hofman A, Rocca WA, Brayne C, et al. The prevalence of dementia in Europe: a collaborative study of 1980–1990 findings. Int J Epidemiol. 1991;20:736–48. doi: 10.1093/ije/20.3.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lobo A, Launer LJ, Fratiglioni L, et al. Prevalence of dementia and major subtypes in Europe: a collaborative study of population-based cohorts. Neurology. 2000;54(11 Suppl 5):S4–S9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rocca WA, Hofman A, Brayne C, et al. Frequency and distribution of Alzheimer's disease in Europe: a collaborative study of 1980–1990 prevalence findings. Ann Neurol. 1991;30:381–90. doi: 10.1002/ana.410300310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kiejna A, Frydecka D, Adamowski T, et al. Epidemiological studies of cognitive impairment and dementia across Eastern and Middle European countries (epidemiology of dementia in Eastern and Middle European Countries) Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26:111–17. doi: 10.1002/gps.2511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Altman DG, Bland JM. Statistics notes: how to obtain the confidence interval from a P value. BMJ. 2011;343:d2090. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sterne JAC, Smith GD. Sifting the evidence—what's wrong with significance tests? Another comment on the role of statistical methods. BMJ. 2001;322:226–31. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7280.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bermejo-Pareja F, Benito-Leon J, Vega S, Medrano MJ, Román GC. Incidence and subtypes of dementia in three elderly populations of central Spain. J Neurol Sci. 2008;264:63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2007.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Imaizumi Y. Mortality rate of Alzheimer's disease in Japan: secular trends, marital status, and geographical variations. Acta Neurol Scand. 1992;86:501–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1992.tb05132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arslantas D, Ozbabalik D, Metintaş S, et al. Prevalence of dementia and associated risk factors in Middle Anatolia, Turkey. J Clin Neurosci. 2009;16:1455–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2009.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leighton AH, Lambo TA, Hughes CC, Leighton DC, Murphy JM, Macklin DB. Psychiatric Disorder Among the Yoruba: A Report From the Cornell-Aro Mental Health Research Project in the Western Region, Nigeria. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rodriguez JJ, Ferri CP, Acosta D, et al. Prevalence of dementia in Latin America, India, and China: a population-based cross-sectional survey. Lancet. 2008;372:464–74. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61002-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Viechtbauer W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J Stat Softw. 2010;36:1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lumley T. rmeta: Meta-Analysis. R package version 2.16, 2009. http://www.R-project.org (4 July 2012, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gurland B, Cross P, Defiguerido J. A cross-national comparison of the institutionalized elderly in the cities of New York and London. Psychol Med. 1979;9:781–88. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700034139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steenland K, MacNeil J, Vega I, Levey A. Recent trends in Alzheimer disease mortality in the United States, 1999 to 2004. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23:165–70. doi: 10.1097/wad.0b013e3181902c3e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Azzimondi G, D'Alessandro R, Pandolfo G, Feruglio FS. Comparative study of the prevalence of dementia in two Sicilian communities with different psychosocial backgrounds. Neuroepidemiology. 1998;17:199–209. doi: 10.1159/000026173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brayne C. Incidence of dementia in England and Wales: the MRC cognitive function and ageing study. Alzeimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2006;20:S47–51. doi: 10.1097/00002093-200607001-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Canadian Study of Health and Aging Working Group. Canadian Study of Health and Aging: study methods and prevalence of dementia. Can Med Assoc J. 1994;150:899–913. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ebly EM, Parhad IM, Hogan DB, Fung TS. Prevalence and types of dementia in the very old: results from the Canadian study of health and aging. Neurology. 1994;44:1593–600. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.9.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hébert R, Lindsay J, Verreault R, Rockwood K, Hill G, Dubois MF. Vascular dementia: incidence and risk factors in the Canadian Study of Health and Aging. Stroke. 2000;31:1487–93. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.7.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hendrie HC, Ogunniyi A, Hall KS, et al. Incidence of dementia and Alzheimer disease in 2 communities: Yoruba residing in Ibadan, Nigeria, and African Americans residing in Indianapolis, Indiana. JAMA. 2001;285:739–47. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.6.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hendrie HC, Osuntokun BO, Hall KS, et al. Prevalence of Alzheimer's disease and dementia in two communities: Nigerian Africans and African Americans. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:1485–92. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.10.1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin RT, Lai CL, Tai CT, Liu CK, Yen YY, Howng SL. Prevalence and subtypes of dementia in southern Taiwan: impact of age, sex, education, and urbanization. J Neurol Sci. 1998;160:67–75. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(98)00225-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu CK, Lin RT, Lai CL, Tai CT. Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia in Taiwan: prevalence and incidence of 2915 elderly community residents. In: Iqbal K, editor. Alzheimer's Disease: Biology, Diagnosis, and Therapeutics. Chichester: Wiley & Sons; 1997. pp. 21–31. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Manfreda J. The epidemiologic challenge: inter-regional and urban-rural differences. In: Wood T, editor. The Challenge of Dementia in Canada—From Research to Practice. Aylmer, Québec: Health Canada; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matthews F, Brayne C Medical Research Council Cognitive Function and Ageing Study Investigators. The incidence of dementia in England and Wales: findings from the five identical sites of the MRC CFA Study. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e193. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.MRC CFAS. Cognitive function and dementia in six areas of England and Wales: the distribution of MMSE and prevalence of GMS organicity level in the MRC CFA Study. The Medical Research Council Cognitive Function and Ageing Study (MRC CFAS) Psychol Med. 1998;28:319–35. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797006272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ogunniyi A, Baiyewu O, Gureje O, et al. Epidemiology of dementia in Nigeria: results from the Indianapolis-Ibadan study. Eur J Neurol. 2000;7:485–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1331.2000.00124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ogunniyi A, Hall KS, Gureje O, et al. Risk factors for incident Alzheimer's disease in African Americans and Yoruba. Metab Brain Dis. 2006;21:235–40. doi: 10.1007/s11011-006-9017-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sulkava R, Heliövaara M, Palo J, Wikström J, Aromaa A. Regional differences in the prevalence of Alzheimer's disease. In: Soininen H, editor. Proceedings of the International Symposium on Alzheimer's Disease, June 12–15, 1988, Kuopio, Finland: Department of Neurology, University of Kuopio. Finland: World Federation of Neurology Research Group on Dementia; 1988. p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sulkava R, Wikstrom J, Aromaa A, et al. Prevalence of severe dementia in Finland. Neurology. 1985;35:1025–29. doi: 10.1212/wnl.35.7.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang ZX, Zahner GE, Román GC, et al. Dementia subtypes in China. Arch Neurol. 2005;62:447–53. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.3.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang ZX, Zahner GE, Román GC, et al. Socio-demographic variation of dementia subtypes in China: methodology and results of a prevalence study in Beijing, Chengdu, Shanghai, and Xian. Neuroepidemiology. 2006;27:177–87. doi: 10.1159/000096131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hendrie HC, Hall KS, Pillay N, et al. Alzheimer's disease is rare in Cree. Int Psychogeriatr. 1993;5:5–14. doi: 10.1017/s1041610293001358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yip PK, Shyu YI, Liu SI, et al. The multidisciplinary project of dementia study in northern Taiwan (DSNT): background and methodology. Acta Neurol Taiwan. 1997;6:210–16. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Adelman S, Blanchard M, Rait G, Leavey G, Livingston G. Prevalence of dementia in African-Caribbean compared with UK-born White older people: two-stage cross-sectional study. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199:119–25. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.086405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Anzola-Perez E, Bangdiwala SI, De Llano GB, De La Vega ME, Dominguez O, Bern-Klug M. Towards community diagnosis of dementia: testing cognitive impairment in older persons in Argentina, Chile and Cuba. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1996;11:429–38. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Copeland JR, Gurland BJ, Dewey ME, Kelleher MJ. Is there more dementia, depression and neurosis in New York? A comparative study of the elderly in New York and London using the computer diagnosis AGECAT. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;151:466–73. doi: 10.1192/bjp.151.4.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ichinowatari N, Tatsunuma T, Makiya H. Epidemiological study of old age mental disorders in the two rural areas of Japan. Jpn J Psychiatry Neurol. 1987;41:629–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.1987.tb00419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Livingston G, Leavey G, Kitchen G, Manela M, Sembhi S, Katona C. Mental health of migrant elders—the Islington study. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;179:361–66. doi: 10.1192/bjp.179.4.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lobo A. The Liverpool-Zaragoza Study: background and preliminary data of a case-finding method for a population study on dementias. In: Dewey ME, Copeland JR, Hofman A, editors. Case Finding for Dementia in Epidemiological Studies. Liverpool, UK: Institute of Human Ageing; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lobo A, Dewey M, Copeland J, Día JL. The prevalence of dementia among elderly people living in Zaragoza and Liverpool. Psychol Med. 1992;22:239–43. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700032906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sousa RM, Ferri CP, Acosta D, et al. Contribution of chronic diseases to disability in elderly people in countries with low and middle incomes: a 10/66 Dementia Research Group population-based survey. Lancet. 2009;374:1821–30. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61829-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Artero S, Fourrier A, Alperovitch A, et al. Vascular factors and risk of dementia: Design of the Three-City Study and baseline characteristics of the study population. Neuroepidemiology. 2003;22:316–25. doi: 10.1159/000072920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.White L, Katzman R, Losonczy K, et al. Association of education with incidence of cognitive impairment in three established populations for epidemiologic studies of the elderly. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47:363–74. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Figueroa R, Steenland K, MacNeil JR, Levey AI, Vega IE. Geographical differences in the occurrence of Alzheimer's disease mortality: United States versus Puerto Rico. Am J Alzheimers Dis. 2008;23:462–69. doi: 10.1177/1533317508321909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Frecker MF. Dementia in Newfoundland: identification of a geographical isolate? J Epidemiol Community Health. 1991;45:307–11. doi: 10.1136/jech.45.4.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Huss A, Spoerri A, Egger M, Roosli M. Residence near power lines and mortality from neurodegenerative diseases: longitudinal study of the Swiss population. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169:167–75. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jorm AF, Henderson AS, Jacomb PA. Regional differences in mortality from dementia in Australia: an analysis of death certificate data. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1989;79:179–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1989.tb08585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Román GC. Gene-environment interactions in the Italy-Argentina “COLOMBO 2000” project. Funct Neurol. 1998;13:249–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gillum RF, Yorrick R, Obisesan TO. Population surveillance of dementia mortality. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2011;8:1244–57. doi: 10.3390/ijerph8041244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Emard JF, Thouez JP, Mathieu J, Boily C, Beaudry M. Repartition geographique de la maladie d'Alzheimer au Saguenay/Lac-Saint-Jean, Québec (Projet IMAGE): resultats preliminaires [Geographical distribution of Alzheimer's disease in Saguenay/Lac-Saint-Jean, Québec, IMAGE project: preliminary findings] Cah Geogr Que. 1992;36:61–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jean H, Emard JF, Thouez JP, et al. Alzheimer's disease: Preliminary study of spatial distribution at birth place. Soc Sci Med. 1996;42:871–78. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00185-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Laditka JN, Laditka SB, Cornman CB, Porter CN, Davis DR. 10th International Conference on Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders (ICAD 2006) Madrid, Spain: 2006. High variation in both Alzheimer's disease (AD) prevalence and factors associated with prevalence suggest a need for national AD surveillance in the United States. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Laditka JN, Laditka SB, Eleazer GP, Cornman CB, Porter CN, Davis DR. High-variation in Alzheimer's disease prevalence among South Carolina counties. J S C Med Assoc. 2008;104:215–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Laditka SB, Laditka JN, Cornman CB, Porter CN, Davis DR. 10th International Conference on Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders (ICAD 2006) Madrid, Spain: 2006. Age-specific prevalence of Alzheimer's disease in a U.S. state with high population risks: Is South Carolina a harbinger of future national prevalence? [Google Scholar]

- 71.Perron M, Veillette S, Emard JF, et al. Aspects of social epidemiology in the study of Alzheimer's disease in Saguenay (Québec)/IMAGE project. Can J Aging. 1993;12:382–98. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhang ZX, Anderson DW, Mantel N. Geographic patterns of parkinsonism-dementia complex on Guam: 1956 through 1985. Arch Neurol. 1990;47:1069–74. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1990.00530100031010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.World Health Organization. Mental Disorders: Glossary and Guide to Their Classification in Accordance With the Ninth Revision of the International Classification of Diseases. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 74.World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organisation; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 75.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 3rd. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 76.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-III-R. 3rd revised. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1987. [Google Scholar]