Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the radiotherapy treatment outcome of patients in stage IE and IIE nasal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma.

Materials and Methods

From August 1999 to August 2009, 46 patients with stage IE and IIE nasal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma were treated by definitive radiotherapy and chemotherapy. 33 patients were treated with chemotherapy followed by radiotherapy (CT + RT) and they received 50.4 Gy in 28 fractions. 13 patients were treated with concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT) and they received 40 Gy in 20 fractions.

Results

The median follow-up period was 4.6-137.6 months (median, 50.2 months) for all patients. The 4-year overall survival was 68.6% and 4-year disease free survival (DFS) was 61.9%. The 4-year locoregional recurrence free survival was 65.0%, and 4-year distant metastasis free survival (DMFS) was 66.2%. For patients treated with CT + RT, 15 patients (45.5%) achieved complete response after chemotherapy, and 13 patients (39.4%) achieved partial response. 13 patients (81.8%) achieved complete response after radiotherapy, and 6 patients (18.2%) achieved partial response. For patients treated with CCRT, 11 patients (84.6%) achieved complete response, and one patient (7.7%) achieved partial response. In univariate analysis, presence of cervical lymph node metastasis was only significant prognostic factor for DFS and DMFS.

Conclusion

This study did not show satisfactory overall survival rate and disease free survival rate of definitive radiotherapy and chemotherapy for stage IE and IIE nasal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma. For patients with cervical lymph node metastasis, further investigation of new chemotherapy regimens is necessary to reduce the distant metastasis.

Keywords: Nasal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma, Radiotherapy, Concurrent chemoradiotherapy

Introduction

Extranodal NK/T cell lymphoma (ENKTL), nasal type is a rare type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma frequently involving the facial midline including the nasal cavity. It usually develops in the nasal cavity, but it can occur anywhere on the upper aerodigestive tract [1]. The incidence rate differs depending on the race. While ENKTL, nasal type is rare in Western countries such as North America and Europe, it is more prevalent in Asia, Central and South America. Accordingly, many researches have been studied in Asian countries including Korea [2-5]. It is referred to as lethal midline granuloma, angiocentric lymphoma which shows tissue necrosis, vascular invasion and necrosis, but it is currently classified as ENKTL cell lymphoma, nasal type according to WHO classification [1,6]. Because it has a wide variety of cell types, immunohistochemistry such as CD56+, CD2+, CD3-, CD3ε+ is helpful in making the diagnosis. Also in most cases, it is associated with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection, therefore demonstration of EBV in the biopsy (by EBV-encoded small nuclear RNA by in situ hybridization) is necessary [1].

According to Ann Arbor staging system, more than half of the patients with ENKTL are diagnosed as Ann Arbor stage I/II confined to the nasal cavity or aerodigestive tract [2]. CHOP chemotherapy followed by involved field radiotherapy is known to be the standard treatment of Ann Arbor stage I/II non-Hodgkin lymphoma such as diffuse large B cell lymphoma [7]. ENKTL is relatively sensitive to radiation, and radiotherapy alone is an effective treatment [8-10]. However, it shows high local recurrence rate and distant metastasis within two years after treatment [3,4]. Furthermore, before radiotherapy, CHOP chemotherapy or CHOP-like chemotherapy does not significantly improve survival [5,11,12].

The combination of radiotherapy and chemotherapy is the mainstay of treatment for ENKTL, nasal type. Owing to its low incidence rate, most data concerning ENKTL are from retrospective analyses and devoid of randomized control trial. Thus there remains a lack of consensus on radiation field, optimal dose and chemotherapy regimen. Most studies have been retrospective and there are various treatment results in even one institution, and the treatment outcome reports on chemotherapy alone or radiotherapy alone are rare. Therefore, in the present study, we analyzed the treatment outcomes and prognostic factors in patients with ENKTL, nasal type of Ann Arber stage I/II treated with both chemotherapy and radiotherapy.

Materials and Methods

1. Patients eligibility and evaluation

Between August 1999 and August 2009, 72 patients diagnosed with ENKTL, nasal type were treated with radiotherapy. Among these patients, forty-six patients with Ann Arbor stage I/II who received chemotherapy were retrospectively analyzed of medical record. Twenty-six patients were excluded for the following reasons: 2 patients did not receive chemotherapy, 5 patients had recurrent disease, 9 patients were initially Ann Arbor stage III or IV, 4 patients did not complete radiotherapy, 4 patients were lost to follow-up just after treatment, 2 patients died within 1 year after treatment by other disease.

All patients were pathologically diagnosed with ENKTL by biopsy, and were staged according to physical examination, blood chemistry, endoscopy of the nasal and oral cavities, CT or MRI of head, neck, chest, and abdomen, and bone marrow aspiration.

2. Treatment

Radiotherapy was designed using computerized dosimetry and was given with a 6-MV. Our institution policy for patients with Ann Arbor stage I/II ENKTL, nasal type was chemotherapy followed by radiotherapy (CT + RT), but since 2006, some patients were enrolled multi-institution clinical trial and received concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT) followed by additional systemic chemotherapy [13]. Patients who were receiving CT + RT were treated with radiotherapy in daily fractions of 1.8 Gy, 5 days per week for a total dose of 50 Gy. Patients who were receiving CCRT were treated with radiotherapy in daily fractions of 2.0 Gy, 5 days per week for a total dose of 40 Gy.

The radiation field covered all involved areas including nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses, and other parts of the aerodisgestive tract such as nasopharynx, oropharynx and hypopharynx if it had tumor invasion. The field was extended to include the cervical region only when the regional lymph nodes were clinically involved.

Thirty-three patients were treated with CT + RT and among them, 22 patients (66.7%) received 3-4 cycles of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisolone (CHOP) and 9 patients (27.3%) received 3 or 6 cycles of ifosfamide, methotrexate, etoposide and prednisone (IMEP), and remaining 2 patients received other chemotherapy. Thirteen patients were treated with CCRT. All except one patient received weekly cisplatin during radiotherapy followed by three cycles of etoposide, ifosfamide, cisplatin, and dexamethasone (VIPD), and one patient received CHOP during radiotherapy.

3. Treatment response and statistical analysis

Treatment response was assessed by clinical symptoms, sign, and radiographic image according to WHO criteria [14]. Complete response (CR) was defined as disappearance of all previous lesions and absence of any new tumor lesions, and partial response (PR) was defined as a decrease of at least 50% in the product of two perpendicular diameters of each measurable lesion. Stable disease (SD) was defined as a decrease of less than 50% or an increase of less than 25% in tumor size, and progressive disease (PD) was defined as greater than 25% increase in tumor size. Local recurrences and distant metastasis were documented by biopsy or imaging studies. Overall survival (OS) was measured from the date of initial radiotherapy to death or to the last follow-up period. Disease-free survival (DFS) was calculated from the date of initial radiotherapy to the time of the first local or distant recurrence or to the last follow-up period or death for any reason. Complete physical exam, blood chemistry, laryngoscopy and CT or MRI of head and neck were performed after 1 months of completion of treatment and they were repeated every 3 to 6 months thereafter to monitor disease progression. OS and DFS were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method. Survival cures were compared by the log-rank test in univariate analysis. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS ver. 12.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), and p ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Prognostic factors included age, primary sites involvement (nasal cavity or sites outside nasal cavity in the upper aerodigestive tract), Ann Arbor stage, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), International Prognostic Index (IPI) score, local invasion, cervical lymph node involvement, timing of radiotherapy.

Results

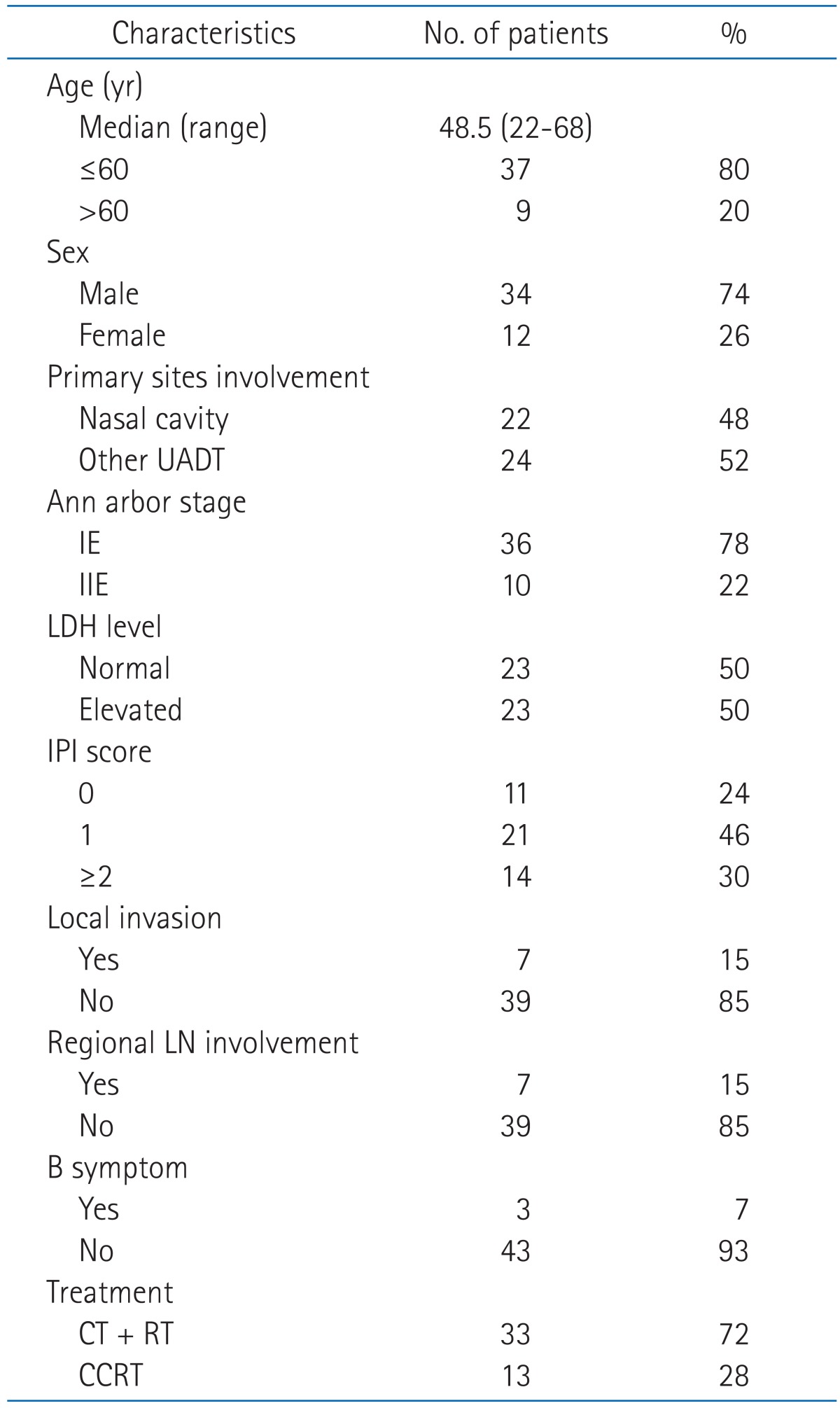

The median follow-up period was 50.2 months (range, 4.6 to 137.6 months) for all patients, but the treatment period was different between patients receiving CT + RT and CCRT, the median follow up period for patients receiving CT + RT was 68.1 months (range, 5.1 to 137.6 months) and for patients receiving CCRT was 28.5 months (range, 5.1 to 137.6 months). None of the patients showed Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status ≥2, and 3 patients (6.5%) appeared "B" symptom. Other patient characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics (n = 46)

UADT, upper aerodigestive tract; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; IPI, International Prognostic Index; LN, lymph node; CT, chemotherapy; RT, radiotherapy; CCRT, concurrent chemoradiotherapy.

Of those patients receiving CT + RT, 2 patients received radiotherapy <50 Gy and 3 patients received ≥55 Gy (range, 30 to 55.8 Gy; median, 50.4 Gy).

Thirty-one patients who received CT + RT underwent clinical response evaluation at the end of chemotherapy. Among these patients, 15 patients (45.5%) achieved CR, 13 patients (39.4%) achieved PR, 2 patients (6.1%) achieved SD, 1 patient showed disease progression. At the end of radiotherapy, 27 patients (81.8%) achieved CR and 6 patients (18.2%) achieved PR. Of 13 patients treated with CCRT, 11 patients (84.6%) achieved CR, 1 patient (7.7%) achieved PR and 1 patient (7.7%) showed disease progression. At the time of analysis, 31 patients (67.4%) were alive without evidence of disease, whereas 15 patients (32.6%) died from disease. The estimated 4-year OS and DFS rates were 68.6% and 61.9%, respectively (Fig. 1A).

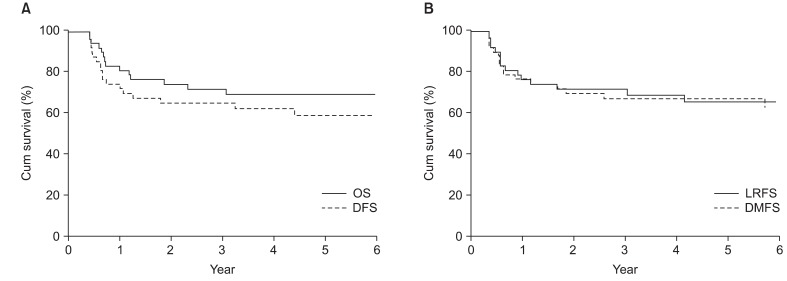

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of survival for all patients. (A) Kaplan-Meier estimates of disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS). (B) Kaplan-Meier estimates of locoregional recurrence free survival (LRFS) and distant metastases free survival (DMFS).

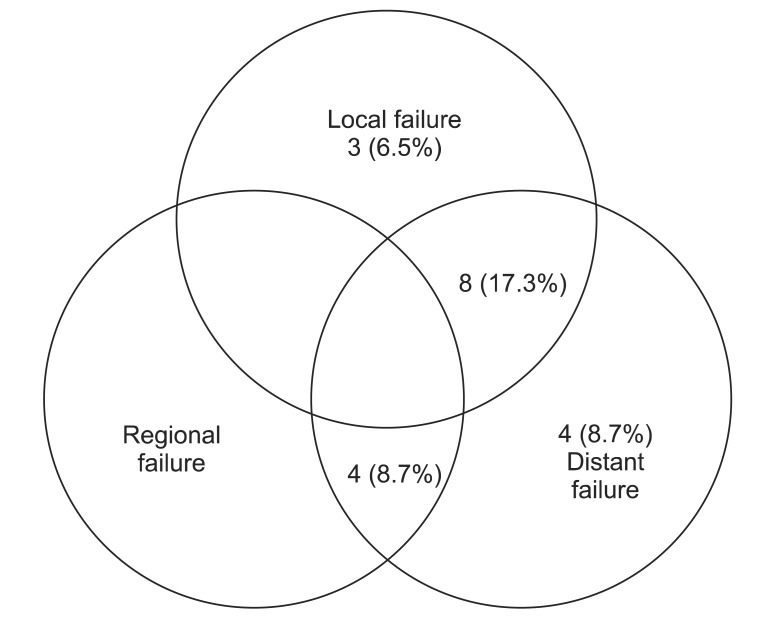

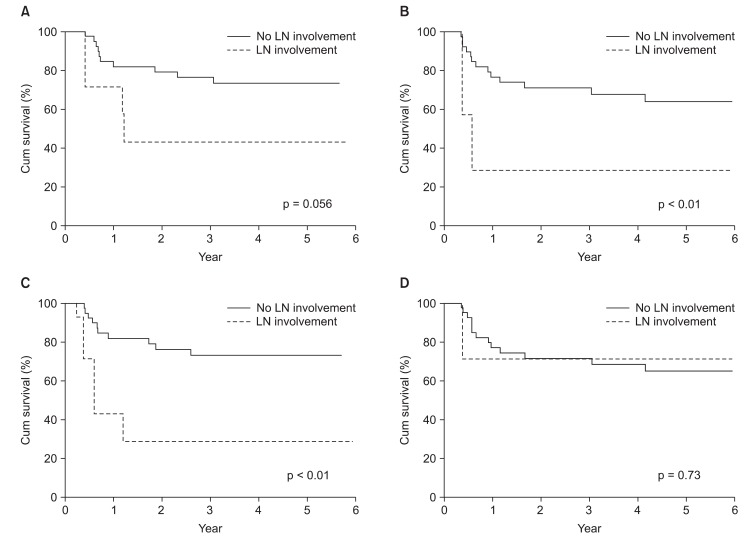

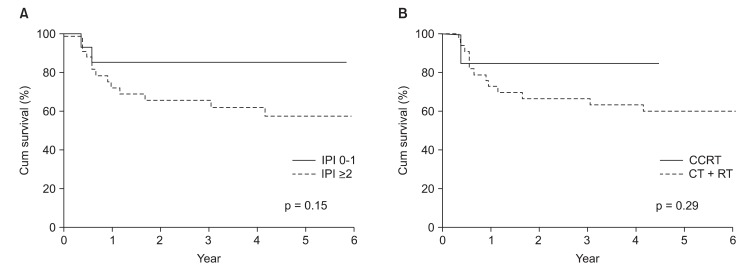

Nineteen patients (41.3%) of 40 patients experienced disease progression. Local relapse was found in only 3 patients (6.5%) and distant metastasis in 4 (8.7%). 8 patients (17.3%) experienced local relapse and distant metastasis and 4 patients (8.7%) experienced cervical lymph node relapse and distant metastasis (Fig. 2). Of the patients with cervical lymph node relapse, 1 patient initially had cervical lymph node involvement. Among fifteen patients with local relapse or cervical lymph node relapse, 4 patients showed local relapse outside of radiation field. The 4-year locoregional free survival (LRFS) and 4-year distant metastasis free survival (DMFS) rate were 65.0% and 66.2%, respectively (Fig. 1B). On univariate analysis, cervical lymph node involvement turned out to be a significant factor influencing both DFS (p < 0.01) and DMFS (p < 0.01), and showed a trend toward a better OS (p = 0.056) (Table 2, Fig 3). Although patients with IPI score of 0-1 receiving CCRT showed higher local control rate, it was not a statistically significant (Table 2, Fig 4).

Fig. 2.

Treatment failure patterns of all patients.

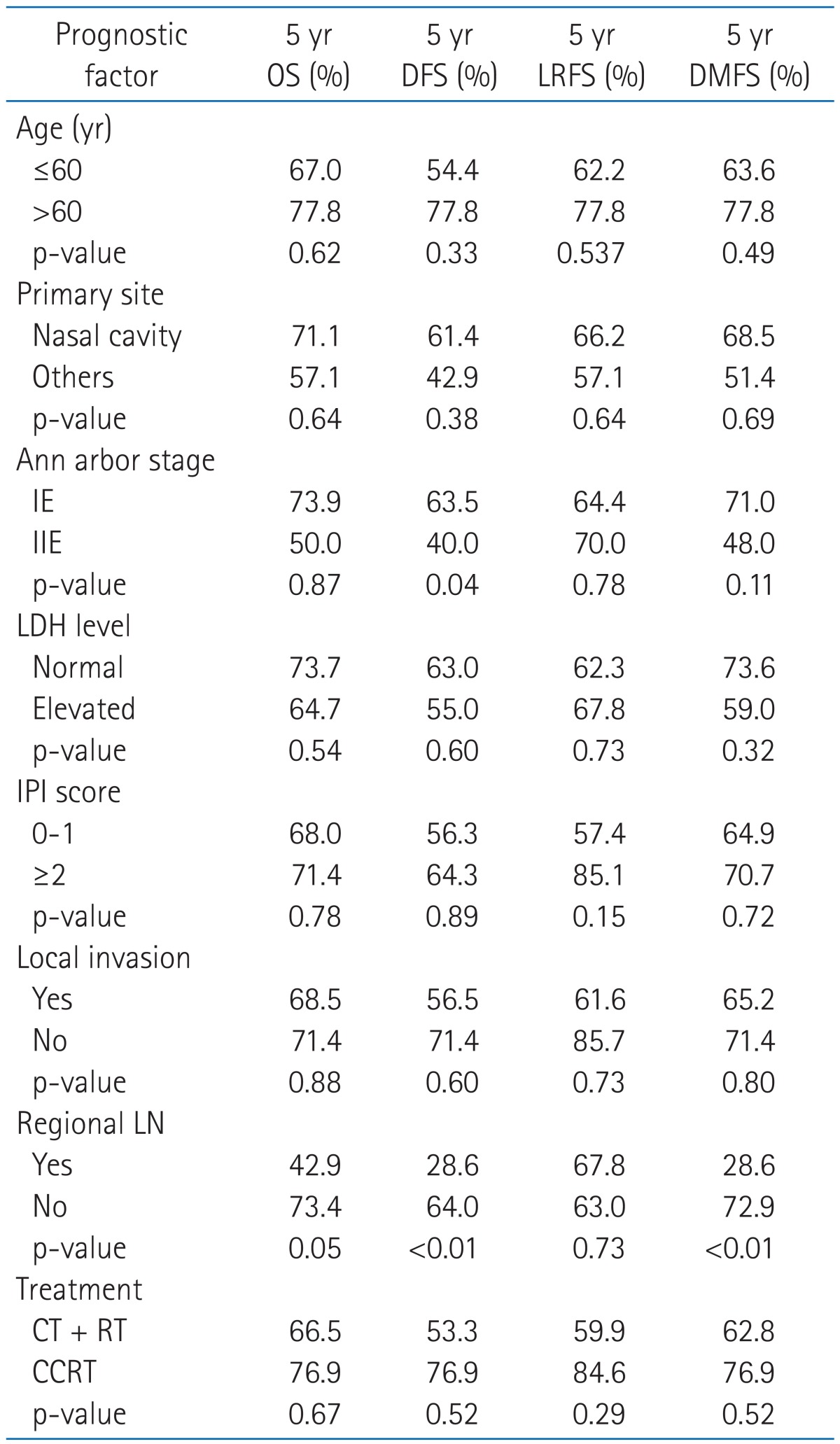

Table 2.

Univariate analysis for locoregional recurrence free survival, distant metastasis free survival, disease free survival and overall survival in all patients

OS, overall survival; DFS, disease free survival; LRFS, locoregional recurrence free survival; DMFS, distant metastasis free survival; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; IPI, International Prognostic Index; LN, lymph node; CT, chemotherapy; RT, radiotherapy; CCRT, concurrent chemoradiotherapy.

Fig. 3.

Survival rates according to regional lymph node (LN) involvement (A) overall survival rate (B) disease free survival rate (C) distant metastasis free survival (D) locoregional recurrence free survival rate.

Fig. 4.

Subgroup analysis of patients according to International Prognostic Index (IPI) score and timing of radiotherapy (A) locoregional recurrence free survival rate according to IPI score (B) locoregional recurrence free survival rate according to timing of radiotherapy. CT, chemotherapy; RT, radiotherapy; CCRT, concurrent chemoradiotherapy.

Discussion and Conclusion

Extranodal NK/T cell lymphoma, nasal type is an aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Although more than half of the patients are diagnosed as localized disease, the overall prognosis is poor. CHOP chemotherapy followed by involved field radiotherapy has become a standard treatment modality for localized disease of intermediate or high grade non-Hodgkin lymphoma [7,15], but CHOP or CHOP-like chemotherapy which is usually used to treat other non-Hodgkin lymphoma have little efficacy in patients with ENKTL. In the study of treatment outcome with similar treatment regimen to non-Hodgkin lymphoma, Kim et al. [12] reported that in patients who were treated with six cycles of CEOP-B chemotherapy including cyclophosphamide, epirubicin, vincristine and bleomycin followed by radiotherapy, CR was achieved in 44.2%, with a median survival of 26.87 months and a median disease free survival of 15.27 months. Kim et al. [5] reported that in 28 patients treated with CHOP or CHOPlike chemotherapy followed by radiotherapy, CR was achieved in 35.6% after chemotherapy, with 2-year disease free survival rate of 22.9% and 2-year overall survival of 44.2%. Wang et al. [16] reported that in patients treated with six cycles CHOP chemotherapy followed by radiotherapy, CR was achieved in 49.1% after chemotherapy, with a 2-year DFS of 61.8% and 2-year OS of 75.6%. This result is better than the previous one, but it is not satisfactory compared with other non-Hodgkin lymphomas. In this study, more than 60% of the patients treated with chemotherapy followed by radiotherapy used CHOP chemotherapy and their 3-year DFS and OS did not show good results either. Thus, the standard treatment of other non-Hodgkin lymphoma does not show satisfactory treatment outcome in ENKTL.

Many studies have reported that early or upfront radiotherapy is essential for good local control [8,9,13,17-19]. As a result of these studies, early applied or upfront radiotherapy showed better the CR rate and survival rate are better than radiotherapy used after chemotherapy [8,9,17,18]. In recent years, two phase II clinical studies about concurrent chemoradiotherapy for localized disease were published [13,19]. Two studies showed high CR rate and improved survival compared to historical studies of chemotherapy followed by radiotherapy. Especially they showed improved local control which local recurrence rate was 3.3-4%. In this study, patients receiving CT + RT had better CR rate, DFS, LRFS, and DMFS compared with patients receiving CCRT. These results imply that radiotherapy for ENKTL is crucial in achieving a good local control. Thus the delay in radiotherapy should be avoided.

Despite the fact that many patients with ENKTL are diagnosed with Ann Arber stage I/II, the pattern of disease progression is very various. Some patients with localized disease can be cured by only radiotherapy, but other patients show failure of local control and development of multi-organ failure during or after the treatment. Furthermore Ann Arbor stage and IPI score applied on non-Hodgkin lymphoma does not reflect the prognosis of ENKTL, so there are continuous efforts in finding new prognostic factor [20-22]. However, studies on the prognostic factor show IPI score such as performance status and LDH level still influence ENKTL [8,10,16-18]. Lee et al. [20] presented a new prognostic model involving cervical lymph node metastasis and Ann Arbor stage as prognostic factors. They divided Ann Arbor stage into stage I/II and stage III/IV, if we focused on only stage I/II patients, B symptom, LDH level and cervical lymph node metastasis can be regarded as influential prognostic factors. This study also shows that cervical lymph node metastasis is the only prognostic factor on disease free survival. Therefore patients who have cervical lymph node metastasis or high IPI score need intensive treatment.

In this study, radiotherapy added to chemotherapy did not show satisfactory improvement in survival rate and local control in the treatment of patients with Ann Arbor stage I/II ENKTL. Concurrent chemoradiotherapy could be helpful to improve local control, but drawing the conclusion is difficult due to small sample size and retrospective design. Cervical lymph node metastasis is an independent prognostic factor for DFS and DMFS. Selection or combination of new systemic chemotherapy agent needs to be investigated to prevent the systemic failure, particularly in patients with cervical lymph node metastasis. This study had some limitations; these include the retrospective design, the use of heterogenous chemotherapeutic regimens, and the small sample size. However, this study is meaningful in that we studied the treatment outcome of patients who received the same radiotherapy regimen in the single institution.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Jaffe ES, Chan JK, Su IJ, et al. Report of the Workshop on Nasal and Related Extranodal Angiocentric T/Natural Killer Cell Lymphomas: definitions, differential diagnosis, and epidemiology. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:103–111. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199601000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Au WY, Weisenburger DD, Intragumtornchai T, et al. Clinical differences between nasal and extranasal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma: a study of 136 cases from the International Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma Project. Blood. 2009;113:3931–3937. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-185256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim GE, Cho JH, Yang WI, et al. Angiocentric lymphoma of the head and neck: patterns of systemic failure after radiation treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:54–63. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.1.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li CC, Tien HF, Tang JL, et al. Treatment outcome and pattern of failure in 77 patients with sinonasal natural killer/T-cell or T-cell lymphoma. Cancer. 2004;100:366–375. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim BS, Kim TY, Kim CW, et al. Therapeutic outcome of extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma initially treated with chemotherapy: result of chemotherapy in NK/T-cell lymphoma. Acta Oncol. 2003;42:779–783. doi: 10.1080/02841860310010682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Diebold J, et al. World Health Organization classification of neoplastic diseases of the hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues: report of the Clinical Advisory Committee meeting-Airlie House, Virginia, November 1997. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:3835–3849. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.12.3835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller TP, Dahlberg S, Cassady JR, et al. Chemotherapy alone compared with chemotherapy plus radiotherapy for localized intermediate- and high-grade non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:21–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807023390104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.You JY, Chi KH, Yang MH, et al. Radiation therapy versus chemotherapy as initial treatment for localized nasal natural killer (NK)/T-cell lymphoma: a single institute survey in Taiwan. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:618–625. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li YX, Coucke PA, Li JY, et al. Primary non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the nasal cavity: prognostic significance of paranasal extension and the role of radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Cancer. 1998;83:449–456. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19980801)83:3<449::aid-cncr13>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li YX, Yao B, Jin J, et al. Radiotherapy as primary treatment for stage IE and IIE nasal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:181–189. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.2573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim WS, Song SY, Ahn YC, et al. CHOP followed by involved field radiation: is it optimal for localized nasal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2001;12:349–352. doi: 10.1023/a:1011144911781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim SJ, Kim BS, Choi CW, et al. Treatment outcome of frontline systemic chemotherapy for localized extranodal NK/T cell lymphoma in nasal and upper aerodigestive tract. Leuk Lymphoma. 2006;47:1265–1273. doi: 10.1080/10428190600565651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim SJ, Kim K, Kim BS, et al. Phase II trial of concurrent radiation and weekly cisplatin followed by VIPD chemotherapy in newly diagnosed, stage IE to IIE, nasal, extranodal NK/T-Cell Lymphoma: Consortium for Improving Survival of Lymphoma study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:6027–6032. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.8592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller AB, Hoogstraten B, Staquet M, Winkler A. Reporting results of cancer treatment. Cancer. 1981;47:207–214. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19810101)47:1<207::aid-cncr2820470134>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horning SJ, Weller E, Kim K, et al. Chemotherapy with or without radiotherapy in limited-stage diffuse aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group study 1484. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3032–3038. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang B, Lu JJ, Ma X, et al. Combined chemotherapy and external beam radiation for stage IE and IIE natural killer T-cell lymphoma of nasal cavity. Leuk Lymphoma. 2007;48:396–402. doi: 10.1080/10428190601059795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang MJ, Jiang Y, Liu WP, et al. Early or up-front radiotherapy improved survival of localized extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal-type in the upper aerodigestive tract. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;70:166–174. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.05.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheung MM, Chan JK, Lau WH, Ngan RK, Foo WW. Early stage nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma: clinical outcome, prognostic factors, and the effect of treatment modality. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;54:182–190. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)02916-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamaguchi M, Tobinai K, Oguchi M, et al. Phase I/II study of concurrent chemoradiotherapy for localized nasal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma: Japan Clinical Oncology Group Study JCOG0211. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5594–5600. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.8295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee J, Suh C, Park YH, et al. Extranodal natural killer T-cell lymphoma, nasal-type: a prognostic model from a retrospective multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:612–618. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim TM, Park YH, Lee SY, et al. Local tumor invasiveness is more predictive of survival than International Prognostic Index in stage I(E)/II(E) extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type. Blood. 2005;106:3785–3790. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-2056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim SJ, Kim BS, Choi CW, et al. Ki-67 expression is predictive of prognosis in patients with stage I/II extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:1382–1387. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]