Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Student counseling centers are responsible for physical, mental and social health of university students. Therefore, this study was conducted to assess the key stakeholders’ opinions on different aspects of the activities performed in these centers.

METHODS:

This qualitative study used focus group discussion. Key stakeholders including university students and key informants from nine randomly selected medical universities participated in the study. After data saturation, thematic analysis was conducted. Themes were drawn out through constant comparative method.

RESULTS:

Based on 243 extracted codes and through comparative analysis, four categories were determined, namely students’ need for students counseling centers, successes and limitations of student counseling centers, student counseling services priorities, and suggestions for service promotion.

CONCLUSIONS:

According to stakeholders’ opinions, youth participation in needs assessment and priority setting processes in real-based situations leads to better performance of counseling services. Empowering the counselors is another point required for better outcomes. In addition, strategic planning and monitoring, along with evaluation of programs, could promote the provided services.

KEYWORDS: Opinion, Stakeholders, University, Counseling

Changes in social, cultural and other aspects of life structure alongside the evolution and expansion of communication network may lead to stressful conditions, especially for the youth. In such circumstances, consulting should play a main helping role in achieving the essential knowledge and skills for a comprehensive understanding of various aspects of problem solving.1 Providing attractive services especially designed for university students could cover a large number of youth groups who may need help.

Student counseling centers (SCCs) provide appropriate counseling and supporting services for clients.2 Considering the important role of these centers, SCCs have been established in universities of medical sciences in Iran since 1995.3 More than three million students are graduated from Iranian public and private universities every year.4 Findings of previous studies emphasized the role of counseling center services in compliance of medical students with their identity in the different dimensions of health.5 Like any other group of young people university students are at risk and therefore individual or group counseling and peer group techniques are proposed as the most effective method to improvement of providing counseling services.6,7 It is noteworthy that since the success of these centers depends on the evidence-based practice documents, the key stakeholders’ opinion could be considered as useful related evidence.

A national study in Iran showed that 87% of students emphasized on the necessity of peer education and counseling meanwhile half of them believed that they needed a specialist group for complicated situations.8 In another study, 6% of students mentioned that they did not have anyone to rely on in difficult conditions.9

Three general categories of problems lead the students toward SCCs including mental and social problems (55%), economic problems (28%), and educational problems (17%).10

Currently, SCCs services offer guidance to social affairs, but there is a need to promote their performance according to students’ real needs.11 Considering the abovementioned issues, we have conducted a qualitative study to explore the key stakeholders’ opinions about challenges and success of SCCs for promotion of future performance.

Methods

This qualitative study collected the data via focus group discussions with participation of service users (students) and service providers (key informants/managers) as an interactive qualitative technique for eliciting new ideas.12 All Iranian universities of medical sciences were divided into three clusters (based on educational level). Three universities were randomly selected to be included in each cluster. Cluster one (type1universities) included Tehran, Shahid Beheshti and Iran Universities of Medical Sciences. Cluster 2 (type 2 universities) consisted of Baghiyatallah, Welfare and Rehabilitation and Qazvin Universities of Medical Sciences. Finally, cluster 3 (type 3 universities) included Uremia, Bushehr and Shahre Kord Universities of Medical Sciences. Service providers with five years of experience in counseling centers and also sophomores or students of higher semesters in all medical fields were studied. Four sessions of focus group discussion (FGD) with managers (two sessions with managers in cluster 1 and one session with each of the other two clusters) were implemented in the Research and Technology Office. Twelve sessions of FGD with students (four sessions in each cluster) were conducted. The FGD sessions were held in the corresponding universities. In addition, medical science students were chosen through random sampling. Since the participants would be more comfortable sharing ideas in a same-gender group,13 each cluster consisted of two male and two female focus groups of 5-8 participants. To obtain homogenous groups and enhance group dynamics,14 in each FGD session, the moderator was the main researcher and the observer and notetakers were trained persons who had related experience. Moreover, FGD sessions were conducted in a quiet room in a neutral location. Two guide questionnaires, one for the students and one for the managers, were used to collect data. Each guide questionnaire consisted of ten main questions that covered the study objectives. For students, the FGD session started with an oral presentation of the scenario of a student who had decided to marry and he/she needed advice. The discussion started with a question related to the case: “What does he/she do for taking advice?”. All guide questionnaires included four main subjects, namely students need for counseling services, successes and limits of student counseling centers, priorities of services offered at student counseling centers, and suggestions for service promotion.

Content analysis was used to analyze the data. The focus group interviews were transcribed and then analyzed manually. The transcripts were read with the intention of deriving ‘meaning units’. The coding scheme was derived theoretically according to the framework of the study. On the other hand, the themes and subthemes were identified from transcripts, providing a basis for generating new codes or modifying the codes developed by induction.

Credibility, dependability, conformability, and transferability are used to describe various aspects of trustworthiness in qualitative methods.15,16 To enhance credibility, we selected participants with different positions (students and key persons/managers). To address conformability, we shared summarized interview findings with the participants at the end of the group discussion (respondent validation). Transferability was considered by attempting to clearly detail methods of data collection, analysis, added quotes, and meaning units. To assess dependability, peer checking was performed by an experienced colleague to re-analyze some of the data. Consistency checks between colleagues were also performed throughout the coding process.17

The participants were informed about the confidentiality of data. They were also informed that participation was voluntary and that they could withdraw at any time during the study. The nature and purpose of the study were explained to each participant before written consents were taken. Permission to audiotape the interview sessions was sought orally prior to the interviews. The results of research were presented to stakeholders. In addition, the process of conducting FGD sessions was approved by the Cultural and Student Affair Offices at each university.

Results

Using content analysis, 243 codes were extracted according to the framework of the study. The identified themes and subthemes founded the basis of new codes inductively. For better understanding, the final results of analyses are presented as four main domains, namely students need for counseling centers, successes and limitations of student counseling centers, priorities of student counseling services, and suggestions for promoting student counseling services.

Students’ need for counseling centers

All participants in key informants FGD sessions agreed on the necessity of student counseling services, especially for students at risk. One of the participants said: “where active centers were known and confidant for the students, their frequent references justified these centers requirement.” (Counselor, Cluster 2). Moreover, most key informant participants mentioned that cooperation of private sector with student counseling centers provides accessibility to various specialists and motivates the students to use these services.

Most participants in the student groups emphasized the need for counseling centers, especially as confidant references for sharing experiences and receiving help in problem solving. Although some others, did not feel such a need and believed that they were mature enough to solve their own problems. In some cases lack of efficacy and unsuccessful previous experiences led to such a belief as one student (female, cluster 1) said: “Counseling is only a motto and could not give you anything more.”.

Successes and limitations of student counseling centers

Participants in key informant groups believed that although SCCs have been relatively successful in achieving their short time goals, they faced serious difficulties in realizing long time goals. “Counseling centers perform acceptable activities considering their available resources, but there are some problems we cannot do anything about. For instance, we cannot help the students with their frustration about future employment and many other serious problems.” stated a counseling center staff member in cluster 1.

In addition, the majority of participants in these groups agreed that cultural problems, such as considering counseling as a taboo, make students unwilling to refer to counseling centers. “The society considers counseling a cultural taboo, thus the output of centers decreases noticeably.” said a counselor in cluster 3.

Weakness in advocacy, poor information, lack of confidence in some centers, structural and organizational problems, and also inefficient use of available potentials were some other weak points discussed by the members of these groups.

Key informant participants mentioned that predicted tasks for student counseling services do not match the existing structure of offices. “The situation of universities is not considered realistically but only idealistically.” declared a counseling center staff member in cluster 3.

A counselor from cluster 2 stated that “Ignoring many important motivator factors for the counselors such as enough financial support and employment improvement, definitely affects their offered services.”.

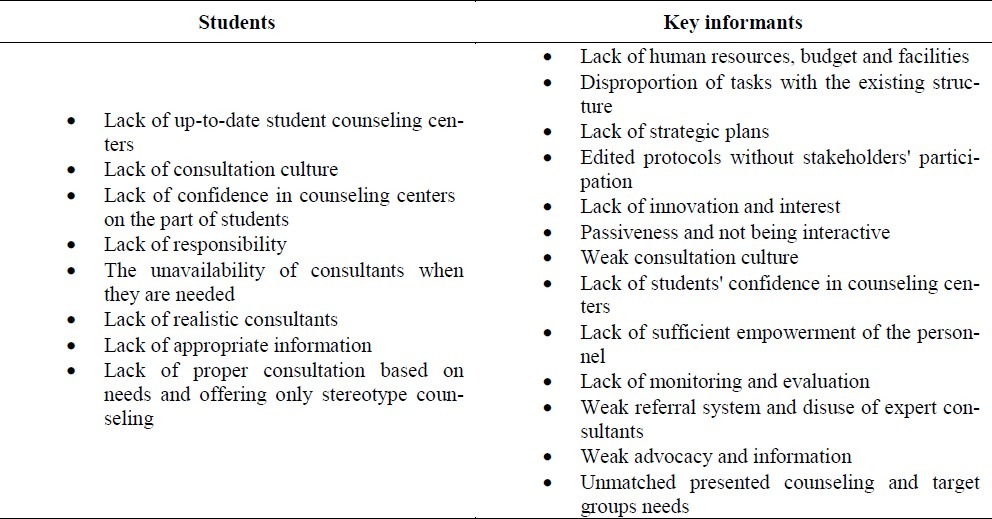

On the other hand, the students believed that improvements must be done in order for SCCs to be successful. Table 1 presents the limitations students face in counseling centers. As it is seen, they considered stereotype counseling, repeated advices, lack of confidence, poor information, and cultural weakness were the main barriers for successful practice of student counseling centers.

Table 1.

Limitation of student counseling services based on key stakeholders opinion.

Student counseling services priorities

The majority of key informant participants indicated the most common problems leading the students to the counseling centers as academic problems, depression and anxiety, frustration and malaise, psychological damage caused by risky behaviors, marriage, interpersonal relationships, financial problems, concerns about the future, employment, and cultural conflicts. As a counselor in cluster 2 said “The students never talk about their real problem at first.” which could be due to lack of confidence, cultural barriers, shame, and fear of official outcomes of the problems.

In the students groups however, the participants introduced mental health, motivation and targeted, financial problems, employment, marriage, and interpersonal relationships as the most common problems they would refer to an SCC for.

Suggestions for promoting student counseling services

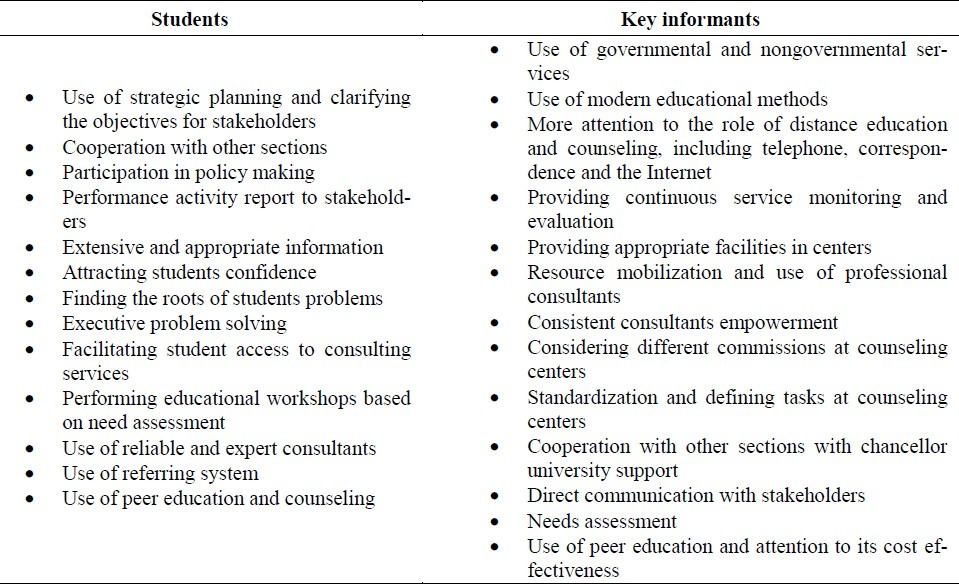

The comments provided by the participants are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Suggested strategies for promoting student counseling services.

The key informants pointed out peer education and peer counseling services must be strengthened in universities since they are available and effective channels with many advantages such as prevention of mental problems and possibility of early intervention. However, they also expressed that some criteria such as popularity, trustworthiness, and academic success must be exactly detected in selection of volunteer peers. “Peers can be effective, but the training is essential in three fields including identification, screening and referring. In addition, the domain of their intervention should be determined.” stated a counseling center staff member in cluster 1. Another counseling center staff member declared that “An SCC would be able to offer better service if it selects appropriate personnel.”. A counselor in cluster 2 also mentioned that “For successful planning some essential factors such as defined indicators, evaluation process, and participatory planning must be considered. Moreover, financial and human resources and other facilities should be provided based on participatory need assessments.”.

Students believed that as peer groups have a common understanding of the situations, they could be more effective. “Everyone who trusts his friend certainly accepts his guidance more than others’.” stated a female student in cluster 4.

They also emphasized the necessity of the presence of an accurate peer trainer and consultants selection process.

The main ideas the student groups presented were as follows:

“Participation of more professional counselors and promotion of interested relationship lead to increasing the efficacy of services.” (Male student, cluster 1).

“The counseling services must be very wide and active. They should recognize potential client students, try to attract them and their confidence, and finally detect and solve their problems.” (Male student, cluster 2).

“If someone's problem is solved effectively, it will be the best propaganda for the center.” (Female student, cluster 3).

Discussion

SCCs, as a part of universities student administration, ultimately aim to promote different aspects of students health such as physical, psychological and social health. The most essential tasks in such services include providing appropriate conditions for students personality development, educational improvement, capacity building and growing compatibility with familial, social, occupational and intellectual situations.18 In the present study, we specifically focused on the participation university students and key informants.

It is noteworthy that both the key informants and students emphasized the absolute and urgent need for SCCs among students. Such results were also found in other similar studies.19

Strengths and weaknesses of student counseling services was another subject discussed in this study. Most participants from all groups believed that capacity building and improvement of counseling centers are the most important points for service promotion. Key informants considered policy making and organizational problems as the most challenging tasks. They mentioned ignoring existing potential and lack of participatory planning as the main management problems.

A challenge emphasized by most participants in all student groups was lack of mutual confidence between clients and counselors. This problem has been emphasized in many other studies which proposed that safe and confident conditions as the first health requirement.20 In another study, young participants also cited cultural problems including negative attitude towards counseling and cultural taboo as the most noticeable problems.21

Our findings were in agreement with a similar research indicating the necessity of basing each health operational planning on a comprehensive need assessment.22 In the present study, student participants introduced need assessment as the first and most reliable method to set priorities in counseling services.

Mental health was a priority mentioned by both key informants and students. Based on professional experiences of key informants “a significant percentage of students refer to SCCs because of depression, anxiety and despair” which was also confirmed in other studies.10–12 Meilman et al., and Lucas and Berkel showed that thinking of suicide, fear, anxiety, and depression were the most common major problems in students referred to the emergency consultation centers.23,24 Another study indicated that students’ mental health needed more attention, better planning, more power investment, and more expert participations.25

Similar to previous related studies,8 we found interpersonal communication skills as another priority mentioned by all student and key informant groups. This issue is currently covered by during school life skill training.

Main ideas students proposed for improving student counseling services were strategy planning, resource mobilization, needs assessment and priority setting, and participatory decision making. Another study highlighted the importance of interrelationships between various service providing sectors, stakeholders’ participation, considering cultural beliefs, and trying different methods for promoting health training.25 Peer group education and counseling were the noticeable suggestions expressed by another researcher.8,26

Due to the vision and design of the present study, it only represents the basic and fundamental views of the challenges SCCs face. It also offers suggestions for better health which should be followed by complimentary detailed researches.

In conclusion, the results of this study indicate that the undeniable need for SCCs should be provided through wide and comprehensive advocacy. Moreover, participatory planning based on systematic needs assessment and priority setting should be considered as the foundation of students’ health promotion.

We finally suggest some key points that lead to SCCs promotion according to the findings of the present study:

Reviewing the objectives, tasks and instructions of SCCs by the Department of Cultural and Student Affairs at the Ministry of Health and Medical Education with the participation of key stakeholders.

Strategic planning for SCCs in each university according to their situation analyses.

Internal and external monitoring and evaluation of the SCCs.

Needs assessment and priority setting of the SCCs.

Participatory interaction with other stakeholders.

Authors’ Contributions

N.P, F.RT, HM and Sh.Dj carried out the design, coordinated the study, participated in most experiments, and prepared the manuscript. MBE provided assistance in the design of the study, coordinated and carried out all experiments, and participated in manuscript preparation. All authors have read and approved the content of the manuscript.

Acknowledgement

This project has been led by the Deputy of Research and Technology, Ministry of Health and Medical Education of IRAN. It was financially supported by United Nations Fund for Population Activities (UNFPA). The authors gratefully thank the Family Planning Society and all participants for their cooperation. We also thank the research team, especially Dr Zeynab Hashemi, for their devoted time.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interests Authors have no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Kaveh M. Text book of public health. 1st ed. Tehran: Ministry of Health and Medical Education, Research and Technology Department, the Committee being computerized medicine and health; 2008. The part of Health counseling; p. 237. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wright PJ, McKinley CJ. Mental health resources for LGBT collegians: a content analysis of college counseling center Web sites. J Homosex. 2011;58(1):138–47. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2011.533632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ministry of Health & Medical Education. Ministry of Health Activities Report: Report of 30 Years Activities of Ministry of Health & Medical Education [Online] 2009. Apr 21, [cited 2010 Apr 20]. Available from: URL: http://behdasht.gov.ir/uploads/final-virayesh%20aval_8602.pdf .

- 4.Statistical Center of Iran. National Statistical Information: Selected Statistical Information [Online] 2010. Apr 2, [cited 2010 Apr 20]. Available from: URL: http://www.sci.org.ir/portal/faces/public/sci/sci.gozide .

- 5.Rodolfa E, Chavoor S, Velasquez J. Counseling services at the University of California, Davis: helping medical students cope. JAMA. 1995;274(17):1396–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.274.17.1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salminen M, Vahlberg T, Ojanlatva A, Kivela SL. Effects of a controlled family-based health education/counseling intervention. Am J Health Behav. 2005;29(5):395–406. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2005.29.5.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Senderowitz J, Hainsworth G, Solter C. A rapid assessment of youth friendly reproductive health services. Pathfinder International. 2003;(4) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramezanitehrani F, Malekafzali H, Peikari N, Djalalinia Sh, Hejazi F. Turkey, Istanbul: 2006. May 3–6, Peer education of reproductive health among youth. Poster session presented at: 9th ESC Congress ‘Improving Life Quality through Contraception and Reproductive Health Care’. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yasamy MT, Shahmohammadi D, Bagheri Yazdi SA, Layeghi H, Bolhari J, Razzaghi EM, et al. Mental health in the Islamic Republic of Iran: achievements and areas of need. East Mediterr Health J. 2001;7(3):381–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tamini BK, Mohammadi Far MA. Mental health and life satisfaction of Iranian and Indian students. Journal of Indian Academy of Applied Psychology. 2009;35(1):137–41. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peykari N, Ramezani Tehrani F, Malekafzali H, Hashemi Z, Djalalinia Sh. An Experience of Peer Education Model among Medical Science University Students in Iran. Iranian Journal of Public Health. 2011;40(1):68–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jeon YH. The application of grounded theory and symbolic interactionism. Scand J Caring Sci. 2004;18(3):249–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2004.00287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parsons M, Greenwood J. A guide to the use of focus groups in health care research: Part 1. Contemp Nurse. 2000;9(2):169–80. doi: 10.5172/conu.2000.9.2.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kitzinger J. Qualitative research.Introducing focus groups. BMJ. 1995;311(7000):299–302. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7000.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lincoln YS, Guba EG. 1st ed. London: Sage Publications; 1985. Naturalistic Inquiry. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24(2):105–12. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rolfe G. Validity, trustworthiness and rigour: quality and the idea of qualitative research. J Adv Nurs. 2006;53(3):304–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin J, Romas M, Medford M, Leffert N, Hatcher SL. Adult helping qualities preferred by adolescents. Adolescence. 2006;41(161):127–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bost ML. A descriptive study of barriers to enrollment in a collegiate Health Assessment Program. J Community Health Nurs. 2005;22(1):15–22. doi: 10.1207/s15327655jchn2201_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kefford CH, Trevena LJ, Willcock SM. Breaking away from the medical model: perceptions of health and health care in suburban Sydney youth. Med J Aust. 2005;183(8):418–21. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2005.tb07107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pledge DS, Lapan RT, Heppner PP, Kivlighan D, Roehlke HJ. Stability and severity of presenting problems at a university counseling center: A 6-year analysis. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 1998;29(4):386–9. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simbar M, Tehrani FR, Hashemi Z. Reproductive health knowledge, attitudes and practices of Iranian college students. East Mediterr Health J. 2005;11(5-6):888–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meilman PW, Hacker DS, Kraus-Zeilmann D. Use of the mental health on-call system on a university campus. J Am Coll Health. 1993;42(3):105–9. doi: 10.1080/07448481.1993.9940824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lucas MS, Berkel LA. Counseling needs of students who seek help at a University Counseling Center: A closer look at gender and multicultural issues. Journal of College Student Development. 2005;46(3):251–66. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sepahvand MA. The study of emotional, behavioral, familial, and personality Problems referred to Lorestan University Student Counseling Center in the 2000-1. Journal of Science and Psychology. 2000;7(1-2):141–50. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peykari N, Ramezani Tehrani F, Malekafzali H. A peer-based study on adolescence nutritional health: A lesson learned from Iran. JPMA. 2011;61(6):549–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]