Abstract

Tumors such as breast, lung, and prostate frequently metastasize to bone, where they can cause intractable pain and increase the risk of fracture in patients. When tumor cells metastasize to bone, they interact with the microenvironment to promote bone destruction primarily through the secretion of osteolytic factors by the tumor cells and the subsequent release of growth factors from the bone. Our recent data suggest that the differential rigidity of the mineralized bone microenvironment relative to that of soft tissue regulates the expression of osteolytic factors by the tumor cells. The concept that matrix rigidity regulates tumor growth is well established in solid breast tumors, where increased rigidity stimulates tumor cell invasion and metastasis. Our studies have indicated that a transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) and Rho-associated kinase (ROCK)–dependent mechanism is involved in the response of metastatic tumor cells to the rigid mineralized bone matrix. In this review, we will discuss the interactions between ROCK and TGF-β signaling, as well as potential new therapies that target these pathways.

Keywords: Bone metastasis, TGF-β, ROCK, Mechanotransduction, Breast cancer, Rigidity

Introduction

As breast cancer progresses, tumor cells frequently metastasize to bone where they become established and begin to produce factors that cause changes in normal bone remodeling. Consequently, nearly 70% of breast cancer patients with advanced disease develop bone metastases that can lead to serious skeletal events such as episodes of intractable bone pain, pathologic fracture, and hypercalcemia [1]. Patients presenting symptoms of tumor-induced bone disease are treated with nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates, such as zoledronic acid, to slow the progression of the disease. Across a broad array of tumor types, zoledronic acid (4 mg intravenously over 15 min every 3–4 weeks) decreased the frequency of skeletal-related events, delayed the time to a first skeletal-related event, and reduced pain [2]. Nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates can delay skeletal tumor growth by inhibiting osteoclast-mediated bone resorption [3] and may also inhibit tumor cell functions such as adhesion, invasion, and proliferation [4, 5]. However, whether nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates directly or indirectly affect tumor cells is a subject under current investigation. Thus, further study of the physical effects of the bone microenvironment on tumor cell gene expression is needed to develop novel therapies targeting both the tumor and the bone microenvironment [5].

Several cytokine products of breast cancers (eg, parathyroid hormone–related protein [PTHrP], interleukin-11, interleukin-8) have been shown to act upon host cells of the bone microenvironment to promote osteoclast formation, allowing for excessive bone resorption [6]. As osteoclasts degrade the surrounding bone, the release of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) from the bone matrix further stimulates secretion of PTHrP by the tumor cells, resulting in a positive feedback loop that accelerates bone resorption [7]. PTHrP is expressed at higher levels in bone metastases from breast cancers than in isolated primary tumors or soft tissue metastases [8, 9]. Other studies demonstrate that primary breast tumors expressing PTHrP display a less invasive phenotype and are therefore less likely to metastasize, suggesting that the regulation of PTHrP at the primary site is distinct from the bone resorption–stimulating action that favors bone metastasis [10]. Together, these findings suggest that environmental factors unique to the bone microenvironment induce tumor cells to express PTHrP after tumor cells become established in bone.

One of the most striking differences between bone and other non-mineralized tissues is that the bone extracellular matrix is approximately 105 to 106 times more rigid. In addition to its osteolytic function in metastatic bone disease, PTHrP also regulates smooth muscle tone in a variety of tissue types. Mechanical distention of the abdominal aorta [11], the uterus, and the bladder [12] has been shown to increase PTHrP expression and secretion in rats [13], suggesting that this molecule is responsive to mechanically transduced signaling. In this article, we review the roles of TGF-β signaling and matrix rigidity on the expression of osteolytic factors such as PTHrP and the establishment and progression of tumor-induced bone disease.

Matrix Rigidity Alters TGF-β Signaling in the Primary Site

Previous studies have shown that matrix rigidity regulates invasiveness at the primary site [14, 15]. Cells sense the rigidity of the matrix through adhesion sites, where integrins provide the mechanical link between the matrix and the cytoskeleton [16]. When cells encounter a rigid matrix, integrins become activated, which initiates trans-membrane signaling by activating focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and Src family kinases at adhesive sites [17]. FAK and Src consequently recruit and activate a number of downstream effectors, including members of the Rho family of small GTPases that stimulate actomyosin contractility and actin remodeling [18]. Blocking Rho GTPase signaling in tumor cells by treating with inhibitors of Rho-associated protein kinase (ROCK), a major downstream effector of RhoA, reduces tumor cell contractility and spreading, which underscores the importance of Rho signaling in cell force generation [19•]. Forces resulting from ROCK-generated contractility can drive cytoskeletal remodeling, resulting in a stiffening of the matrix surrounding the mammary tumor [15, 19•] that subsequently alters integrin-dependent signaling within the tumor cells [15]. This positive feedback loop driving matrix remodeling in mammary tumors can lead to a 10-to 100-fold increase in matrix rigidity [14]. In contrast, tumor cells in the mineralized bone microenvironment adhere to and directly interact with a rigid matrix (through integrin αvβ3[20]) that is at least 108-fold stiffer than the primary site (1.7–2.9×1010 Pa [21] for bone versus 1.5×102 Pa for breast tissue [22]).

In addition to their roles in mediating ROCK-generated contractility, integrins can also directly modulate TGF-β responses [23]. Integrin αvβ3 and Src interact with TGF-β to induce epithelial-mesenchymal transitions (EMTs) of mammary epithelial cells [17], which also requires Src-dependent phosphorylation of TGF-β type II receptor [24]. In addition, the ability of TGF-β to promote tumorigenesis and EMT has been suggested to proceed through the integration of Smad2/3 signaling with RhoA and mitogenactivated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways [25]. Although TGF-β is associated with EMT in mammary tumors, in bone metastases TGF-β stimulates secretion of PTHrP by the tumor cells. Thus, after tumor cells become established in the bone microenvironment, they respond differently to exogenous TGF-β. We hypothesized that the rigid mineralized bone matrix drives changes in cytoskeletal structure and cell contractility that alter TGF-β signaling within the tumor cells to initiate expression of factors required for bone resorption.

Responses of Cells to Mechanically Transduced Signals Are Regulated by ROCK

ROCK is well established as a regulator of mechanotransduction and integrin-mediated signaling. Activation of integrins resulting from cellular interactions with rigid matrices stimulates Rho GTPase-dependent actomyosin contractility. Consequently, blocking Rho GTPase signaling in tumor cells by treating with ROCK inhibitors reduces tumor cell contractility and spreading [19•]. In healthy (ie, non–tumor-bearing) bone tissue, extracellular matrix rigidity regulates differentiation of osteoprogenitor cells through activation of MAPK downstream of the RhoA–ROCK signaling pathway, and inhibition of ROCK delays osteogenesis [26••]. Interestingly, in this study expression of markers of osteoblastic differentiation (eg, alkaline phosphatase) was reported to increase with matrix rigidity. ROCK has also been implicated in breast cancer metastasis to bone, as evidenced by observations that ROCK expression is higher in metastatic human mammary tumors relative to non-metastatic tumors [27••]. Furthermore, molecular or pharmacologic inhibition of ROCK using the drug Y-27632 (BioSource, Carlsbad, CA), which inhibits the kinase activity of ROCK, decreased cell proliferation in vitro and metastasis to bone in vivo [27••]. In another recent study, single cell populations (SCPs) derived from MDA-MB-231 cells showed increased migration to proliferation when cultured on matrices with rigidities corresponding to the native rigidities of the organs where metastasis was observed [28••]. Thus, SCPs targeted specifically to bone proliferated faster and were more invasive on rigid tissue culture polystyrene compared with soft polyacrylamide (PAA) gels. These observations suggest that the differential rigidity of the mineralized bone microenvironment relative to soft tissue may regulate tumor cell fate.

The Differential Rigidity of the Bone Microenvironment Regulates Osteolytic Gene Expression by Tumor Cells

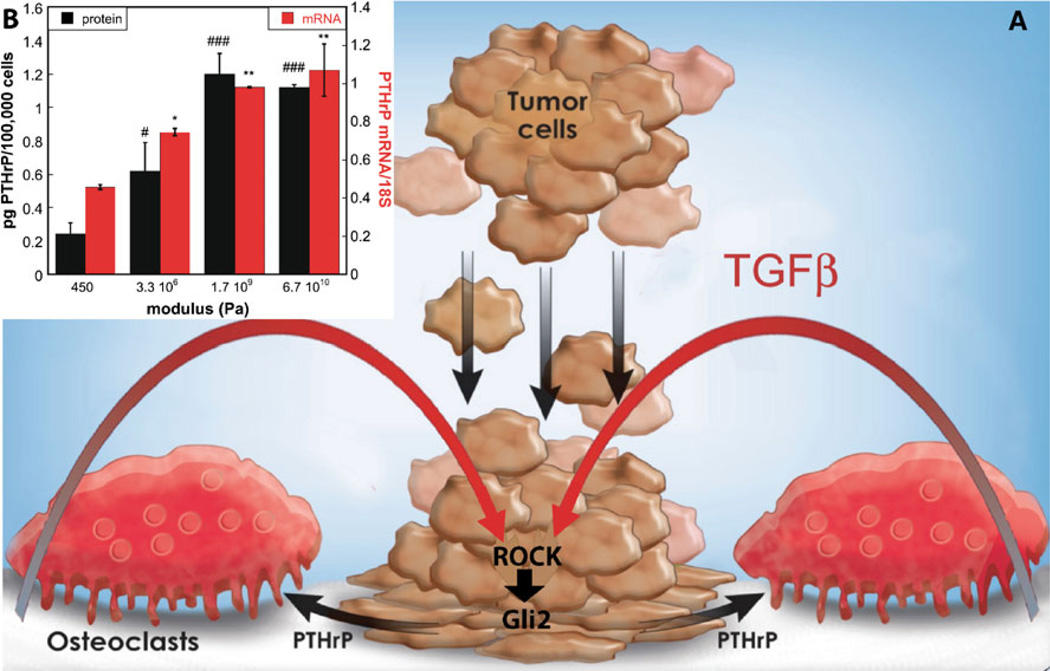

We have recently reported that Gli2 and PTHrP expression by MDA-MB-231 tumor cells is higher when the cells are cultured on rigid matrices with elastic moduli approximating that of bone (Fig. 1)[29••]. Furthermore, molecular or pharmacologic (using Y-27632) inhibition of ROCK blocks the ability of tumor cells to respond to rigid matrices, which inhibits the expression of Gli2 and PTHrP resulting in the blockade of bone destruction [29••]. To test our hypothesis that cytoskeleton-dependent forces mediated by ROCK regulate PTHrP expression in tumor cells, we designed a two-dimensional tumor cell monoculture system using matrices with tunable rigidities [29••]. Previous studies investigating the effects of matrix rigidity on cell migration, differentiation, and invasion have used in vitro two-dimensional cell culture on model substrates, such as Matrigel (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ) [30], cross-linked gelatin [31], and synthetic hydrogels [32]. However, the applicability of these substrates to the bone microenvironment is limited, due to the inability to achieve a sufficiently high elastic modulus that is relevant to mineralized bone tissue. The elastic moduli of several tissue types are listed in Table 1.

Figure 1.

a Schematic illustrating the effects of matrix rigidity on expression of osteolytic factors by metastatic tumor cells. Tumor cells attach to the mineralized bone extracellular matrix through integrins, resulting in increased Rho-associated kinase (ROCK)–generated contractility within the cells. Transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ) released from the extracellular matrix as a consequence of osteoclast-mediated bone resorption drives increased tumor cell Gli2 and parathyroid hormone–related protein (PTHrP) expression. b MDA-MB-231 cells cultured on two-dimensional substrates simulating tissues including breast (450 Pa), smooth muscle (3.3×106 Pa), trabecular bone (1.7×109 Pa), and cortical bone (6.7×1010 Pa) show increased expression of PTHrP with increasing substrate rigidity. *, # = P<0.05; **, ## = P<0.01; ***,### = P<0.005 compared with 450 Pa value

Table 1.

Rigidity of selected tissues

| Tissue type | Elastic modulus (Pa) |

|---|---|

| Brain | 102–104 |

| Lung | 4×102 |

| Breast | 8×102 |

| Muscle | 0.12–1.0×105 |

| Fat | 2×104 |

| Artery | 0.1–3.8×106 |

| Areolar connective tissue | 0.6–1.0×105 |

| Smooth muscle | 5×106 |

| Bone | 17.1–28.9×109 |

In our study, we prepared PAA hydrogels as a model for breast tissue (800 Pa) [19•], poly(ester urethane) films [33]as a model for tissues ranging from smooth muscle (5×106 Pa) to trabecular bone (8.7–11.4×109 Pa) [34], and glass (67×109 Pa) as a model for cortical bone (17.1–28.9× 109 Pa) [23]. We measured changes in gene expression by MDA-MB-231 tumor cells in response to the rigidity of the substrate. PTHrP expression was lowest on PAA hydrogels and increased with modulus for values up to 109 Pa, at which point it became constant (Fig. 1). Although the expression of Gli2 and PTHrP increased significantly on rigid matrices, many of the genes identified previously to be associated with metastasis [35] to bone showed minimal changes in expression [29••]. Interestingly, matrix rigidity was observed to regulate osteolytic gene expression by the tumor cells over a range of elastic modulus values exceeding that of areolar connective tissue and smooth muscle and approaching that of trabecular bone [29••]. Thus, the tumor cells responded to matrix rigidities in the 106 to 109 Pa range, which exceeds the modulus of gels previously used in mechanotransduction experiments by several orders of magnitude. This observation contrasts with previous studies suggesting that cells cultured on substrates having a modulus equal to or greater than that of stiff (eg, >105 Pa) gels are in a state of isometric contraction such that cells can no longer respond to increases in matrix rigidity [36].

ROCK Alters TGF-β Signaling in the Bone Microenvironment

TGF-β has long been established to be a critical factor in the positive feedback loop known as the vicious cycle associated with tumor-induced bone disease. Originally published by Mundy [37], this concept suggests that TGF-β released from the mineralized bone matrix during osteoclast-mediated resorption stimulates the expression of PTHrP by tumor cells, which in turn further stimulates resorption and the continuing release of TGF-β from the matrix [7]. Subsequent papers have elucidated the details of the TGF-β signaling pathways involved in the vicious cycle, indicating that both Smad and p38 MAPK signaling are required [38]. Despite the strong evidence for a predominant role of TGF-β in this process, the vicious cycle concept alone does not explain what occurs early in tumor establishment before bone resorption, nor does it explain why tumor cells in soft tissue sites (where TGF-β is also present) have not been shown to express PTHrP [8, 9]. Therefore, we suggest that both TGF-β and the rigid mineralized bone matrix are required for tumor-induced bone destruction, as illustrated by the pathway diagram in Fig. 1.

The mechanotransduction mediator ROCK has been demonstrated to be regulated by TGF-β signaling. For example, ROCK is downstream of TGF-β in vitreoretinal disease, and inhibition of ROCK can block TGF-β activity completely [39••]. Furthermore, it has been reported that ROCK is downstream of TGF-β and that p38 MAPK, ROCK, and Smads are required for TGF-β–mediated growth inhibition [40]. Due to the established role of ROCK in TGF-β signaling and mediating cellular responses to rigidity, we speculated that ROCK may be required for TGF-β to regulate PTHrP. To test our hypothesis, we investigated the effects of ROCK and TGF-β inhibition and stimulation using pharmacologic agents and genetically modified cells to identify the signaling pathways through which rigidity regulates gene expression. As recently published, we found that ROCK is required for tumor cells to respond to the rigid mineralized bone matrix and TGF-β [29••]. Specifically, MDA-MB-231 cells expressing a dominant-negative form of ROCK did not respond to stimulation by exogenous TGF-β. Similarly, expression of a dominant-negative form of the TGF-β type II receptor also blocked the ability of the cells to respond to rigid matrices. Thus, both TGF-β and ROCK are necessary for the increased expression of Gli2 and PTHrP on rigid matrices [29••].

Treatment of Osteolytic Bone Lesions

Bisphosphonates are currently the clinical standard of care for treating patients with bone metastases, and have been demonstrated in clinical trials to be safe and efficacious by reducing the risk of osteoporotic fractures [41•]. However, the recent discovery of clinical complications observed with long-term bisphosphonate treatments, including osteonecrosis of the jaw and atypical subtrochanteric fractures, has necessitated a search for new alternatives. Inhibitors of receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand (RANKL) have been shown to block osteoclast activity and improve bone density and strength in preclinical models [42]. Moreover, a highly specific human antibody against RANKL (denosumab) reduced bone turnover and increased bone density in clinical studies in osteoporosis and breast cancer patients [43]. Marketed as XGEVA (Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA), denosumab is indicated for prevention of skeletal-related events in patients with bone metastases from solid tumors [43]. However, denosumab may also present safety risks in some patients, including hypocalcemia and osteonecrosis of the jaw.

Both bisphosphonates and denosumab block bone resorption by directly inhibiting the activity of osteoclasts. Although blocking RANKL has been recently shown to have anticancer activity in mouse models [44], anticancer activity of denosumab has not yet been demonstrated in human patients. As an alternative strategy for blocking both tumor growth and bone resorption, TGF-β inhibitors have thus far been very successful in preclinical studies, with several groups demonstrating that inhibition of TGF-β reduces metastasis to soft tissues [45••] and bone [46••]. In healthy (ie, tumor-free) mice, treatment with the TGF-β inhibitors 1D11 (Genzyme, Cambridge, MA) and SD-208 (Scios, Inc., Sunnyvale, CA) increased bone density and biomechanical properties as well as numerous measures of bone quality (eg, trabecular bone architecture and mineral: collagen ratio) [47•]. Blocking TGF-β also increased the numbers of osteoblasts and decreased the numbers of osteoclasts in the bone marrow of healthy mice. However, despite their promising success in preclinical studies, TGF-β inhibitors exhibit biphasic effects that potentially limit their use in the clinic [48••]. Specifically, in genetic mouse models in which TGF-β signaling is stimulated, TGF-β inhibits formation of mammary tumors at early stages, but can promote metastasis of tumors at later stages [48••]. These observations suggest that although TGF-β inhibitors may block bone resorption in patients with bone metastases, they could increase tumor cell growth in the primary site. Therefore, treating human patients with TGF-β inhibitors would likely be challenging, especially those with a primary mass and multiple metastases.

The limitations of TGF-β inhibitors underscore the need for more specific inhibitors of tumor growth in bone. Inhibiting downstream molecules, such as ROCK or Gli2, could potentially be an alternative treatment strategy. The ROCK inhibitors Fasudil (Tocris Bioscience, Ellisville, MO) and Y-27632 have been used successfully in preclinical models of pulmonary and cardiac disease. Furthermore, clinical studies have shown that Fasudil is a safe and efficacious treatment for patients with severe pulmonary hypertension [49••]. Fasudil is currently being used clinically for the treatment of cerebral vasospasms, and is also being evaluated in clinical studies for other cardiovascular uses, indicating that the drug, which acts as a mechanotransduction inhibitor, is well tolerated by patients [50]. Considering that ROCK is required for Gli2 and PTHrP expression, as well as the clinical safety and efficacy of Fasudil in cardiovascular applications, the use of Fasudil to target tumors in bone may be a potential alternative strategy for treatment of tumor-induced bone disease.

Conclusions

Patients with tumor-induced bone disease are currently treated with drugs that block osteoclast-mediated bone resorption, such as bisphosphonates and RANKL inhibitors (denosumab). However, due to complications associated with these drugs there remains a compelling clinical need for therapies that specifically target tumor cells in bone. Although preclinical studies have shown that TGF-β inhibitors improve bone quality and slow the progression of metastatic bone disease, the clinical use of these drugs may be difficult due to their adverse effects on normal cells and the primary tumor. In vitro studies have shown that expression of Gli2 and PTHrP by osteolytic tumor cells is increased when cultured on rigid substrates with elastic moduli approaching that of bone, and that both ROCK and TGF-β signaling are required for the increased PTHrP expression observed on rigid matrices. Thus, inhibition of ROCK may more specifically block rigidity-mediated TGF-β signaling. Blocking the ability of the tumor cells to respond to the rigidity of the bone microenvironment is a potentially useful treatment strategy, since ROCK inhibitors such as Fasudil have been used clinically for other diseases without complications.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge financial support from the National Institutes of Health Breast Cancer SPORE (P50 CA098131), P01 CA040035, and Tumor Microenvironment Network (TMEN) (U54 CA126505) grants.

Footnotes

Disclosure Conflicts of interest: J.A. Sterling: none; S.A. Guelcher: has been a consultant and has received funding for his laboratory from Osteotech, Inc.

Contributor Information

Julie A. Sterling, Department of Veterans Affairs: Tennessee Valley Healthcare System (VISN 9), Nashville, TN, USA, Julie.sterling@vanderbilt.edu Department of Cancer Biology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, 1235 MRB IV, 2222 Pierce Avenue 37232, Nashville, TN 37235, USA; Center for Bone Biology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, USA.

Scott A. Guelcher, Center for Bone Biology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, USA Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, Vanderbilt University, 2400 Highland Avenue, 107 Olin Hall, Nashville, TN 37235–1604, USA, Scott.guelcher@vanderbilt.edu.

References

- 1.Guise T, Yin J, Taylor S, Kumagai Y, Dallas M, Boyce B, et al. Evidence for a causal role of parathyroid hormone-related protein in the pathogenesis of human breast cancer-mediated osteolysis. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:1544–1549. doi: 10.1172/JCI118947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith MR. Zoledronic acid to prevent skeletal complications in cancer: corroborating the evidence. Cancer Treat Rev. 2005;31(Suppl 3):19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stresing V, Daubine F, Benzaid I, Monkkonen H, Clezardin P. Bisphosphonates in cancer therapy. Cancer Lett. 2007;257:16–35. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Daubine F, Le Gall C, Gasser J, Green J, Clezardin P. Antitumor effects of clinical dosing regimens of bisphosphonates in experimental breast cancer bone metastasis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:322–330. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coleman RE, Lipton A, Roodman GD, Guise TA, Boyce BF, Brufsky AM, et al. Metastasis and bone loss: advancing treatment and prevention. Cancer Treat Rev. 2010;36:615–620. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sterling JA, Edwards JR, Martin TJ, Mundy GR. Advances in the biology of bone metastasis: how the skeleton affects tumor behavior. Bone. 2011;48:6–15. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yin JJ, Selander K, Chirgwin JM, Dallas M, Grubbs BG, Wieser R, et al. TGF-beta signaling blockade inhibits PTHrP secretion by breast cancer cells and bone metastases development. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:197–206. doi: 10.1172/JCI3523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Southby J, Kissin MW, Danks JA, Hayman JA, Moseley JM, Henderson MA, et al. Immunohistochemical localization of parathyroid hormone-related protein in human breast cancer. Cancer Res. 1990;50:7710–7716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Powell GJ, Southby J, Danks JA, Stillwell RG, Hayman JA, Henderson MA, et al. Localization of parathyroid hormone-related protein in breast cancer metastases: increased incidence in bone compared with other sites. Cancer Res. 1991;51:3059061. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henderson MA, Danks JA, Slavin JL, Byrnes GB, Choong PF, Spillane JB, et al. Parathyroid hormone-related protein localization in breast cancers predict improved prognosis. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2250–2256. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pirola CJ, Wang HM, Strgacich MI, Kamyar A, Cercek B, Forrester JS, et al. Mechanical stimuli induce vascular parathyroid hormone-related protein gene expression in vivo and in vitro. Endocrinology. 1994;134:2230–2236. doi: 10.1210/endo.134.5.8156926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamamoto M, Harm SC, Grasser WA, Thiede MA. Parathyroid hormone-related protein in the rat urinary bladder: a smooth muscle relaxant produced locally in response to mechanical stretch. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:5326–5330. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Philbrick WM, Wysolmerski JJ, Galbraith S, Holt E, Orloff JJ, Yang KH, et al. Defining the roles of parathyroid hormone-related protein in normal physiology. Physiol Rev. 1996;76:127–173. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1996.76.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paszek MJ, Zahir N, Johnson KR, Lakins JN, Rozenberg GI, Gefen A, et al. Tensional homeostasis and the malignant phenotype. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:241–254. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paszek MJ, Weaver VM. The tension mounts: mechanics meets morphogenesis and malignancy. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2004;9:325–342. doi: 10.1007/s10911-004-1404-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Geiger B, Bershaksky A. Exploring the neighborhood: adhesioncoupled cell mechanotransducers. Cell. 2002;110:139–143. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00831-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galliher AJ, Schiemann WP. Beta3 integrin and Src facilitate transforming growth factor-beta mediated induction of epithelialmesenchymal transition in mammary epithelial cells. Breast Cancer Res. 2006;8(4):R42. doi: 10.1186/bcr1524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arias-Salgado EG, Lizano S, Sarkar S, Brugge JS, Ginsberg MH, Shattil SJ. Src kinase activation by direct interaction with the integrin beta cytoplasmic domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:13298–13302. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2336149100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Butcher DT, Alliston T, Weaver VM. A tense situation: forcing tumour progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:108–122. doi: 10.1038/nrc2544.. This review highlights the role of mechanical forces in the invasion and progression of breast tumors.

- 20.Desgrosellier JS, Cheresh DA. Integrins in cancer: biological implications and therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:9–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc2748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galliher AJ, Schiemann WP. Src phosphorylates Tyr284 in TGF-beta type II receptor and regulates TGF-beta stimulation of p38 MAPK during breast cancer cell proliferation and invasion. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3752–3758. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schneider JG, Amend SR, Weilbaecher KN. Integrins and bone metastasis: integrating tumor cell and stromal cell interactions. Bone. 2011;48:54–65. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moore SW, Roca-Cusachs P, Sheetz MP. Stretchy proteins on stretchy substrates: the important elements of integrin-mediated rigidity sensing. Dev Cell. 2010;19:194–206. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumar S, Weaver VM. Mechanics, malignancy, and metastasis: the force journey of a tumor cell. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2009;28:113–127. doi: 10.1007/s10555-008-9173-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bakin AV, Rinehart C, Tomlinson AK, Arteaga CL. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase is required for TGFbeta-mediated fibroblastic transdifferentiation and cell migration. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:3193–3206. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.15.3193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Khatiwala CB, Kim PD, Peyton SR, Putnam AJ. ECM compliance regulates osteogenesis by influencing MAPK signaling downstream of RhoA and ROCK. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24:886–898. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.081240.. This study demonstrates that osteoblast differentiation is regulated by the rigidity of the extracellular matrix in bone through ROCK, and that blocking ROCK delays differentiation.

- 27. Liu S, Goldstein RH, Scepansky EM, Rosenblatt M. Inhibition of rho-associated kinase signaling prevents breast cancer metastasis to human bone. Cancer Res. 2009;69:8742–8751. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1541.. This study demonstrates that molecular or pharmacologic inhibition of ROCK blocks metastasis of breast tumors to bone, and overexpression of ROCK confers a metastatic phenotype to a non-metastatic cell line. It is also suggested that inhibition of ROCK could represent a novel therapy for treatment of breast cancer metastases.

- 28. Kostic A, Lynch CD, Sheetz MP. Differential matrix rigidity response in breast cancer cell lines correlates with the tissue tropism. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6361. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006361.. This study demonstrates that SCPs derived from MDA-MB-231 cells showed increased migration to proliferation when cultured on matrices with rigidities corresponding to the native rigidities of the organs where metastasis was observed. Thus, SCPs targeted specifically to bone proliferated faster and were more invasive on rigid tissue culture polystyrene compared with soft PAA gels.

- 29. Ruppender NS, Merkel AR, Martin TJ, Mundy GR, Sterling JA, Guelcher SA. Matrix Rigidity Induces Osteolytic Gene Expression of Metastatic Breast Cancer Cells. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15451. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015451.. This study demonstrates that osteolytic breast and lung tumor cells cultured on substrates with rigidities comparable to that of mineralized bone tissue show increased expression of Gli2 and PTHrP compared with cells cultured on soft substrates. Furthermore, both ROCK and TGF-β are required for the increased PTHrP expression on rigid substrates.

- 30.Zaman MH, Trapani LM, Sieminski A, MacKellar D, Gong H, Kamm RD, et al. Migration of tumor cells in 3D matrices is governed by matrix stiffness along with cell-matrix adhesion and proteolysis. PNAS. 2006;103:10889–10894. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604460103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alexander NR, Branch KM, Iwueke IC, Guelcher SA, Weaver AM. Extracellular matrix rigidity promotes invadopodia activity. Curr Biol. 2008;18:1295–1299. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.07.090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Engler AJ, Sen S, Sweeney HL, Discher DE. Matrix elasticity directs stem cell lineage specification. Cell. 2006;126:677–689. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guelcher SA, Dumas J, Srinivasan A, Didier JE, Hollinger JO. Synthesis, mechanical properties, biocompatibility, and biodegradation of polyurethane networks from lysine polyisocyanates. Biomaterials. 2008;29:1762–1775. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gibson LJ, Ashby MF. Cellular solids: structure and properties. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kang Y, Siegel PM, Shu W, Drobnjak M, Kakonen SM, Cordo’n-Cardo C, et al. A multigenic program mediating breast cancer metastasis to bone. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:537–549. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00132-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Discher DE, Janmey P, Wang YL. Tissue cells feel and respond to the stiffness of their substrate. Science. 2005;310:1139–1143. doi: 10.1126/science.1116995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mundy GR. Mechanisms of bone metastasis. Cancer. 1997;80:1546–1556. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19971015)80:8+<1546::aid-cncr4>3.3.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kakonen SM, Selander KS, Chirgwin JM, Yin JJ, Burns S, Rankin WA, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta stimulates parathyroid hormone-related protein and osteolytic metastases via Smad and mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:24571–24578. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202561200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kita T, Hata Y, Arita R, Kawahara S, Miura M, Nakao S, et al. Role of TGF-beta in proliferative vitreoretinal diseases and ROCK as a therapeutic target. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:17504–17509. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804054105.. This study elucidates the critical role of TGF-β in mediating cicatricial contraction in proliferative vitreoretinal diseases. ROCK, a key downstream mediator of TGF-β and other factors, might become a unique therapeutic target in the treatment of proliferative vitreoretinal diseases.

- 40.Kamaraju AK, Roberts AB. Role of Rho/ROCK and p38 MAP kinase pathways in transforming growth factor-beta-mediated Smad-dependent growth inhibition of human breast carcinoma cells in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:1024–1036. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403960200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Shane E. Evolving data about subtrochanteric fractures and bisphosphonates. N Engl J Med. 2010 May 13;362:1825–1827. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1003064.. Bisphosphonates, the major class of drugs used to treat osteoporosis, decrease osteoclast-mediated bone resorption and bone turnover markers and increase bone mineral density. They have been shown to be safe and reduce the risk of osteoporotic fractures.

- 42.McClung MR. Inhibition of RANKL as a treatment for osteoporosis: preclinical and early clinical studies. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2006;4:28–33. doi: 10.1007/s11914-006-0012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lipton A, Steger GG, Figueroa J, Alvarado C, Solal-Celigny P, Body JJ, et al. Extended efficacy and safety of denosumab in breast cancer patients with bone metastases not receiving prior bisphosphonate therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:6690–6696. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gonzalez-Suarez E, Jacob AP, Jones J, Miller R, Roudier-Meyer MP, Erwert R, et al. RANK ligand mediates progestin-induced mammary epithelial proliferation and carcinogenesis. Nature. 2010;468:103–107. doi: 10.1038/nature09495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ganapathy V, Ge R, Grazioli A, Xie W, Banach-Petrosky W, Kang Y, et al. Targeting the Transforming Growth Factor-beta pathway inhibits human basal-like breast cancer metastasis. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:122. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-122.. This study shows that TGF-β plays an important role in both bone and lung metastases of breast cancer. Furthermore, inhibiting TGF-β signaling shows a therapeutic effect that is independent of the tissue tropism of the metastatic tumor cells. Targeting TGF-β signaling is a potentially useful therapeutic approach for treating metastatic basal-like breast cancer.

- 46. Mohammad KS, Javelaud D, Fournier PG, Niewolna M, McKenna CR, Peng XH, et al. The Transforming Growth Factor-{beta} Receptor I Kinase Inhibitor SD-208 Reduces the Development and Progression of Melanoma Bone Metastases. Cancer Res. 2011;71:175–184. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2651.. This study demonstrates that therapeutic targeting of TGF-β may prevent the development of melanoma bone metastases and decrease the progression of established osteolytic lesions.

- 47. Edwards JR, Nyman JS, Lwin ST, Moore MM, Esparza J, O'Quinn EC, et al. Inhibition of TGF-β signaling by 1D11 antibody treatment increases bone mass and quality in vivo. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25:2419–2426. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.139.. This study demonstrates that blocking TGF-β with 1D11 increases the population of osteoblasts and decreases the population of active osteoclasts in the marrow, significantly increasing bone volume and quality.

- 48. Tan AR, Alexe G, Reiss M. Transforming growth factor-beta signaling: emerging stem cell target in metastatic breast cancer? Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;115:453–495. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0184-1.. This study demonstrates that in genetic mouse models in which TGF-β signaling is stimulated, TGF-β inhibits formation of mammary tumors at early stages, but can promote metastasis of tumors at later stages. These observations suggest that although TGF-β inhibitors may block bone resorption in patients with bone metastases, they could possibly increase tumor cell growth in the primary site.

- 49. Barman SA, Zhu S, White RE. RhoA/Rho-kinase signaling: a therapeutic target in pulmonary hypertension. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2009;5:663–671. doi: 10.2147/vhrm.s4711.. This paper reviews the extensive animal studies reporting that increased RhoA/ROCK signaling is important in the pathogenesis of pulmonary hypertension by stimulating enhanced construction and remodeling of the pulmonary vasculature. Both preclinical and clinical studies suggest that ROCK inhibitors are effective for treatment of severe pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) with minimal safety risk, which underscores the potential of ROCK inhibitors as a new class of drugs for treatment of PAH.

- 50.Olson MF. Applications for ROCK kinase inhibition. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20:242–248. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]