Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Few studies have examined prediction of schizophrenia outcome in relation to brain MRI measures. In this study, remission status at the time of discharge was examined in relation to admission cortical thickness for childhood-onset schizophrenia probands. We hypothesized that total, frontal, temporal, and parietal gray matter thickness would be greater in patients who subsequently remit.

METHOD

The relationship between admission cortical brain MRI thickness and remission status at the time of discharge an average of 3 months later was examined for 56 individuals (32 males) ages 6 through 19 diagnosed with childhood-onset schizophrenia. Cortical thickness was measured across the cerebral hemispheres at admission. Discharge remission criteria were adapted from the 2005 Remission in Schizophrenia Working Group criteria.

RESULTS

Patients remitted at discharge (n=16 (29%)) had thicker regional cortex in left orbital-frontal, left superior and middle temporal and bi-lateral post-central and angular gyri (all p values ≤ 0.008).

CONCLUSION

Our results provide neuroanatomic correlates of clinical remission in schizophrenia and evidence that response to treatment may be mediated by these cortical brain regions.

Keywords: Childhood-onset Schizophrenia, MRI, Remission, Cortical thickness

Introduction

Childhood-onset schizophrenia (COS), defined as onset of psychosis before age 13, is a rare, severe form of the disorder1. True episodes are very rare in patients with COS and most experience an insidious illness onset and a chronic course. With respect to anatomic brain MRI findings, comparable abnormalities have been demonstrated in the adult onset version of the disorder (AOS) and COS2, 3. Specifically, AOS and COS cortical abnormalities include diminished total, frontal and temporal grey matter and increased lateral ventricles3–5. Based on the few studies examining baseline neuroanatomic predictors of schizophrenia outcome, the temporal lobe6, left prefrontal cortex7, and ventricle volumes8 have been found to be predictive of future symptomatic, functional, and diagnostic outcome, respectively. However, the literature is inconsistent with other studies reporting no relationships between baseline MRI and clinical outcome9–11.

A helpful addition to studying resilience in schizophrenia was provided by the Remission in Schizophrenia Working Group which established a set of symptom severity-based remission criteria12. These criteria consist of low to mild core symptom severity and encompass the three validated dimensions of schizophrenia (negative symptoms, disorganization, and psychoticism)12. Mild symptom severity criteria lasting at least six months were used because of previous failed efforts defining chronic illness remission as absence of symptoms, and remission in other psychiatric disorders such as anxiety disorders has been defined by mild, minimally impairing symptoms12. Reliable and valid symptom ratings scales (e.g., SAPS/SANS) were selected for the purposes of practicality and objectivity, and scale items which map onto both the above 3 dimensions and the DSM-IV schizophrenia diagnostic criteria were selected. Subsequent publications have supported the clinical validity of the work group’s taxonomy13 and have reported that remission status is predicted by negative symptoms, duration of untreated symptoms, early response to medication, marital status, education14, 15, baseline social functioning16, and baseline severity17.

While empirical investigations have addressed social and symptom predictors, there have been no investigations of cortical predictors of remission. Cortical grey matter is thinner in COS samples relative to healthy controls3, and grey matter thickness has been shown to be associated with intelligence18 and overall functioning in healthy siblings of patients with COS (e.g., cortical thickness was positively related to GAS scores in bilateral frontal and temporal cortices) 19. In this study, we examined admission total and regional cortical thickness in relation to discharge remission status for a group of 56 inpatients with COS.

We hypothesized that COS participants who remit would have greater baseline/admission overall, frontal, temporal, and parietal cortical thickness. Frontal and temporal regions were chosen based on their documented abnormality in schizophrenia, and parietal gray matter was hypothesized to be thicker in subjects with COS who remit as this region has been shown to normalize in COS during adolescence (i.e., parietal cortical thickness abnormalities diminish during adolescence)3. Our hypotheses involve groups classified according to the Working Group remission criteria without the six month duration criterion, as our participants are not typically hospitalized for six or more months.

Method

Participants

Since 1991, we have prescreened material from over 2000 referred cases and conducted over 300 in-person screenings. Ninety-four of these individuals met DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia with onset of psychosis before their 13th birthday. Further details of patient recruitment and selection are described elsewhere20,21. Fifty-six participants h(32 males)ad an admission MRI scan suitable for cortical thickness estimation (i.e., no excessive motion artifacts) and had clinical ratings reasonably close to their discharge date (mean difference between discharge date and date of rating was seven days (SD=11 days)). Exclusion criteria were a history of significant medical problems, substance abuse, or an IQ below 70 prior to the onset of psychosis. Most of the participants included in the current study were also used in previous imaging studies2,3,4.

Although our sample is followed longitudinally at two year intervals, the variability in follow-up treatment and environmental support received by participants makes it difficult to determine follow-up remission status in a homogeneous manner. We thus limited the current investigation to NIH discharge remission status, which precludes our ability to determine stability of remission over time but permits us some control over environment/therapeutic milieu, compliance, and quality of care when determining remission status.

Treatment

The duration of hospitalization lasted a mean of 17.9 weeks (SD= 5.7 weeks); for 44 (78.6%) of the 56 participants included in this paper, this entailed a trial of clozapine. Treatment consisted of medication adjustment, milieu treatment, regular family meetings, occupational and recreational therapy, and a two week drug free period in the first month of hospitalization. Weekly physician ratings, nurses notes, occupational and recreation therapy notes, and teacher notes were obtained during hospitalization. Most participants were admitted to one of three double blind medication studies: clozapine vs. haloperidol20, clozapine vs.olanzapine22 and aripiprazole v risperidone (Rapoport et al., unpublished data), and after the blind was broken, medications were adjusted, augmented, or changed on an individualized basis. Children were discharged when they were considered optimally stabilized. In addition to antipsychotic medications (see Table 1), children were also discharged on anticonvulsants (valproic acid(n=1), gabapentin(n=3), divalproex(n=3), levetiracetam(n=1)), benzodiazepines (clonazepam(n=2), lorazepam(n=1)), SSRIs (sertraline(n=9), escitalopram(n=1), citolopram(n=1), and stimulants (methylphenidate(n=3) dextroamphetamine (n=2)). Discharged medication differed from admission medication by dose and/or medication for all participants.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for remitted and non-remitted participants with childhood-onset schizophrenia

| Remitted (n=16) | Not Remitted (n=40) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Mean(SD) | Mean(SD) | t(df) or Mann- Whitney U z score | p | |

| Age at Psychosis Onset | 9.78(1.60) | 10.32(2.09 | z=1.53 | 0.12 |

| Years Ill at Scan | 3.83(2.28) | 3.80(2.01) | t=.05(52) | 0.96 |

| Age at Scan | 13.61(2.06) | 14.17(2.50) | t=0.79(54) | 0.43 |

| ASQ+ Score | 6.13(9.09) | 8.85(8.02) | z=1.38 | 0.17 |

| Socio Economic Status | 2.44(1.26) | 2.80(0.99) | z=1.02 | 0.31 |

| Full Scale IQ | 74.93(17.66) | 66.67(14.34) | z=1.28 | 0.20 |

| GAS++ at Admission | 32.44(8.48) | 30.60(10.66) | t=0.61(54) | 0.54 |

| GAS at Discharge | 51(9.82) | 42(7.57) | 3.72(53) | 0.0005 |

| Days from Scan to Discharge Rating | 99.19 (23.88) | 98.53 (42.66) | t=.074(48)* | 0.94 |

| Total Cerebral Volume (GM + WM + Lat. ventricles) | 1158.70(156.06) | 1116.02(118.69) | t=1.11(54) | 0.27 |

| Gray Matter | 700.04(86.53) | 667.88(75.82) | t=1.38(54) | 0.17 |

| Mean Cortical Thickness | 3.92(0.42) | 3.73(0.34) | t=1.79(54) | 0.08 |

|

| ||||

| Count | Count | Chi-Square(df) | p | |

|

| ||||

| Sex F:M | 7:9 | 17:23 | .007(df=1) | 0.93 |

| Admission Antipsychotic Meds** | ||||

| One atypical | 6 | 14 | na | exact p= 0.15 |

| Two atypicals | 0 | 9 | ||

| Typical | 6 | 11 | ||

| Both typical and atypical | 4 | 4 | ||

| No medications | 0 | 2 | ||

| Discharge Antipsychotic Medication | ||||

| clozapine | 11 | 31 | na | exact p =0.24 |

| clozapine + haloperidol | 0 | 2 | ||

| olanzapine | 4 | 4 | ||

| olanzapine + chlorpromazine | 1 | 0 | ||

| Other Atypical(quetiapine or risperidone) | 0 | 2 | ||

t for equal variances not assumed

Austism Screening Questionnaire

Children’s Global Assessment of Functioning Scale

Atypicals included clozpine(8), olanzapine(11), aripiprazole(4), ziprasidone (1), quetiapine (11), risperidone (11); typicals included haloperidol (8), thiothixine (3), thioridazine(1), chlorpromazine(4), perphenazine(1), flufenazine(2), pimozide(1), molindone (1), loxapine (1), trifluoperazine(2)

Materials/Assessments

We used age-appropriate versions of the Wechsler intelligence scales, including the WISC-R23, WISC-III24, WAIS-R25, WAIS-III26 and the WASI27 to measure intelligence, the Hollingshead scale28 to measure socio-economic status (SES) (higher scores reflect lower SES), the Autism Screening Questionnaire (ASQ) 29 to measure developmental delay, and the Children’s Global Assessment of Functioning score (GAS)30 to measure overall functioning.

Remission Criteria

The Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) and the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS), which assess positive and negative symptoms respectively, were the ratings scales used in determining remission. They consist of 34 (SAPS) and 25 (SANS) items, and ratings are made on a likert scale ranging from 0 (absence of symptom) to 5 (severe)31,32. Ratings were made by staff psychiatrists, and inter-rater reliability was required of all raters (ICC > 0.70). SAPS and SANS ratings closest to a participant’s discharge date from the NIH inpatient child psychiatric unit were used. In accordance with criteria set forth by the Remission in Schizophrenia Working Group (2005), we classified a child as remitted given mild severity (ratings ≤2) on SAPS item numbers 7 (global rating of hallucinations), 24 (repetitive or stereotyped behavior), 25 (global rating of bizarre behavior), and 34 (global rating of formal thought disorder), and SANS items 7 (lack of vocal inflections), 13(global rating of alogia), 17 (global rating of avolition-apathy), and 22 (global rating of anhedonia-asociality). Because the six-month duration criterion set forth by the Remission in Schizophrenia Working Group cannot be established for most of our participants, we can only assert non-sustained remission. For the purposes of simplicity, we will refer to this non-sustained remission as “remission” with the understanding that we can not determine sustained remission as our participants are not typically hospitalized for six or more months.

The research protocol was approved by the NIH institutional review board. Written informed consent was obtained from parents and patients over 18; written informed assent was obtained from minors.

MRI Acquisition and Image Analysis

Participants were typically scanned within two weeks following inpatient admission. T1-weighted images with contiguous 1.5-mm slices in the axial plane and 2.0-mm slices in the coronal plane were obtained with 3D spoiled gradient recalled echo in the steady state on a 1.5-T General Electric Signa scanner (Milwaukee, WI). Imaging parameters were echo time of 5 ms, repetition time of 24 ms, flip angle of 45°, number of excitations equals 1, and 24 cm field of view. The images were collected in a 192×256 acquisition matrix and were 0-filled in k space to yield an image of 256×256 pixels, resulting in an our effective voxel resolution of 0.9375 × 0.9375 × 1.5 cc. Head placement was standardized as previously described33. MRI scans were registered into standardized space using a linear transformation and corrected for non-uniformity artifacts34. Registered and corrected volumes were segmented with an advanced neural net classifier35 and gray and white matter surfaces were fitted with a surface deformation algorithm36,37. This algorithm first determines the white matter surface, then expands outward to find the gray matter-CSF intersection. As a result, gray and white matter surfaces with over 80,000 polygons each are fit and non-linearly aligned38 so each vertex of the white matter surface corresponds to a gray matter surface counterpart, thereby generating linked polygons on the gray and white matter surfaces. Cortical thickness can be defined as the distance between linked vertices of the gray and white matter boundaries. We used a 30mm surface based blurring kernel, as it has been found to maximize statistical power while minimizing false positives39, and cortical thickness was calculated in native space at 40,962 cortical points.

This cortical thickness extraction method has been validated using a phantom brain40, population simulation39, and through manual measurement using this 1.5T image acquisition and resolution in both child and adult populations 41,42. It has also been able to capture the established pattern of cortical degeneration within the medial temporal lobes in Alzheimer’s disease43. However, cortical thickness measurement for four regions (left and right insula, right cuneus, and right parahippocampus) did not meet validity criteria41 and thus are not addressed in this study.

Statistical Analysis

Demographics

We tested demographic differences between groups using t tests or Mann Whitney U tests (if the normality assumption was violated) for continuous variables, chi-square tests of independence for categorical variables, and exact tests for categorical variables if there was an expected cell count less than five.

Cross-cortex group comparisons

We performed a linear model at each of the 40,962 cortical points with gray matter thickness as the dependent measure and group membership (remitted v not-remitted) as the independent variable. We then projected t statistics onto corresponding cortical points on a template brain to visualize group differences. To account for increased risk of type I errors, we set a t threshold of 2.65 (corresponding to a p value of 0.01 given our degrees of freedom) as the lower limit for significance at each cortical point. We calculated mean cortical thickness by averaging values across all cortical points for each scan/participant.

Regional analyses

For each gyri (defined using a probabilistic atlas)38,44 with significant group differences (based on results from the cross-cortex group comparison), we selected only the statistically significant cortical points (p < .01). We then averaged these points within a gyri per scan/participant to represent summary values. We conducted t tests on these averaged values, and calculated Cohen’s ds (mean1- mean2 divided by the pooled standard deviation) to summarize significant group effects within each gyrus. Additionally, we conducted analyses of covariance which controlled for mean cortical thickness to determined if group differences on averaged thickness values would survive. Effect sizes for adjusted means were also calculated (adjusted mean1 –adjusted mean2 divided by the square root of the model mean square error). Finally, we conducted receiver operating characteristics (ROC) analyses and single predictor logistic regression analyses with remission status as the dependent variable and summary thickness values as the independent variables to examine the accuracy with which remission status can be determined based on admission cortical thickness. Data were screened for outliers and statistical assumptions were checked for demographic and regional thickness analyses. We set alpha at 0.01 for the cross-cortex group comparisons, and for all other tests, we used an alpha of 0.05. All statistical tests were 2-tailed. Statistical analyses were conducted using R, SPSS version 12.0 and SAS version 9.0.

Results

Sample Demographics

Twenty nine percent (n=16) of our sample met modified criteria for remission upon discharge. The two groups (participants who remitted vs. those who did not) were statistically comparable relative to age at scan, age at psychosis onset, years ill at scan, ASQ score, socio-economic status, sex, Full Scale IQ, admission GAS score, number of days between scan and discharge ratings, total cerebral volume, total grey matter, and average cortical thickness. As such, we did not include these variables as covariates in our primary analysis. There were no significant relationships between remission status at discharge and either admission or discharge antipsychotic medication. As expected, the discharge GAS scores were significantly higher in the group who remitted (see Table 1).

Group Cortical Thickness Differences

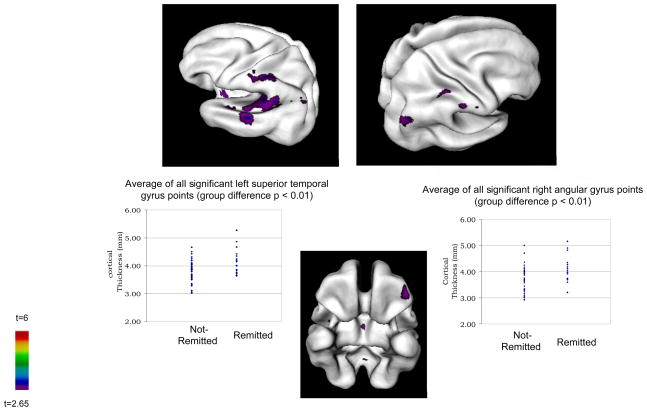

There was a trend for greater mean cortical thickness in the group of COS who remitted (p=.08) (see Table 1). Figure 1 shows that at the t cutoff of 2.65, the group of COS who remitted had several fairly circumscribed areas of significantly thicker cortex in frontal, temporal and parietal lobes. Specifically, significant differences were evident in the superior and middle left temporal gyri, the left orbital frontal gyrus, and bilateral angular and postcentral gyri. There were no points where the group of COS who remitted had significantly thinner cortex. Differences in the insula and inferior regions have not yet been validated and are not addressed here.

Figure 1.

Areas where participants who remitted at discharge (n=16) had significantly thicker cortex than non-remitters (n=40) at admission scan

Regional Differences

The number of cortical points that went into each average thickness measure ranged from 34 (right post central) to 158 (superior temporal). Table 2 contains the means, standard deviations, t and p values, and effect sizes for the significant points averaged within each gyri (i.e., for all scans, all significant points within a given gyrus were isolated and averaged to quantify significant group differences within a gyrus). Effect sizes fell in the large range (≥0.80). After covarying for mean cortical thickness, all group differences remained significant and effect sizes fell in the medium-large and large ranges.

Table 2.

Group differences: Adjusted and unadjusted statistics for significant points averaged within each gyri

| Unadjusted Model | Adjusted Model- Covariate= Mean Cortical Thickness | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| Remitted (n=16) | Not Remitted (n=40) | Remitted (n=16) | Not Remitted (n=40) | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Mean(SD) | Mean(SD) | t(df=54) | p | Effect Size | Adjusted Mean(SE) | Adjusted Mean(SE) | F(df=1,53) | p | Effect Size | |

| Left Frontal Orbital Gyrus | 4.07(0.51) | 3.70(0.41) | 2.89 | 0.005 | 0.85 | 3.94 (0.06) | 3.75(0.04) | 5.94 | 0.02 | 0.74 |

| Left Superior Temporal Gyrus | 4.16(0.46) | 3.79(0.39) | 3.08 | 0.003 | 0.91 | 4.03(0.05) | 3.84(0.03) | 8.42 | 0.005 | 0.88 |

| Left Middle Temporal Gyrus | 4.41(0.50) | 4.00(0.42) | 3.07 | 0.003 | 0.91 | 4.26(0.05) | 4.06(0.03) | 9.35 | 0.003 | 0.93 |

| Left Angular Gyrus | 3.87(0.41) | 3.51(0.38) | 3.13 | 0.003 | 0.93 | 3.75(0.05) | 3.56(0.03) | 8.75 | 0.005 | 0.90 |

| Left Post Central Gyrus | 3.46(0.40) | 3.13(0.35) | 3.10 | 0.003 | 0.92 | 3.37(0.07) | 3.17(0.04) | 6.19 | 0.02 | 0.76 |

| Right Angular Gyrus | 4.12(0.51) | 3.71(0.47) | 2.90 | 0.005 | 0.86 | 3.96(0.06) | 3.77(0.04) | 7.72 | 0.01 | 0.85 |

| Right Post Central Gyrus | 3.56(0.38) | 3.23 (0.35) | 3.13 | 0.003 | 0.93 | 3.45(0.054) | 3.27(0.03) | 7.65 | 0.008 | 0.85 |

Logistic Regression and ROC analyses

The seven single variable predictor logistic regression results indicated positive relationships between summary thickness values and remission status (all p values < .01), with larger thickness values significantly associated with greater likelihood of remission. Sensitivity levels were poor (18.8% to 37.5%) but specificity levels were all 90% and above, as most cases were classified into the largest group (not remitted). ROC analysis results indicated poor to fair categorization accuracy (area under the curve falling between .70 and .75 with .50 equivalent to chance) (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Results from single variable logistic regression analyses and single variable receiver operating characteristics (ROC) analyses classifying participants with childhood-onset schizophrenia who remitted after an inpatient hospitalization

| Significant points averaged within each gyri | Coefficient (SE) | Wald Chi-Square (df=1) | p | Odds Ratio* | Sensitivity (remitted correctly classified) | Specificity (not-remitted correctly classified) | Percent Correctly Classified Total (n=56) | ROC Analyses- Area Under the Curve Total (n=56) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left Orbital Frontal Gyrus | 1.90(0.79) | 5.70 | 0.017 | 6.66 | 18.8% | 95.0% | 73.2% | 0.70 |

| Left Superior Temporal Gyrus | 2.23(0.86) | 6.72 | 0.01 | 9.34 | 25.0% | 92.5% | 73.2% | 0.72 |

| Left Middle Temporal Gyrus | 2.07(0.77) | 7.15 | 0.007 | 7.92 | 37.5% | 95.0% | 78.6% | 0.71 |

| Left Angular Gyrus | 2.20(0.82) | 7.18 | 0.007 | 9.05 | 31.3% | 92.5% | 75.0% | 0.75 |

| Left Post Central Gyrus | 2.29(0.86) | 7.04 | 0.008 | 9.87 | 31.5% | 90.0% | 75.0% | 0.74 |

| Right Angular Gyrus | 1.76(0.70) | 6.35 | 0.012 | 5.83 | 18.8% | 95.0% | 73.2% | 0.73 |

| Right Post Central Gyrus | 2.51(0.94) | 7.06 | 0.008 | 12.28 | 25.0% | 92.5% | 73.2% | 0.74 |

Predicted change in odds of remitting for a unit increase in the predictor

Discussion

This is the first study to examine the relationship between cortical thickness at baseline (or any MRI measure) and subsequent remission status based on modified criteria proposed by Andreasen and colleagues (2005). Our results are consistent with prior reports of frontal and temporal volumes as predictors of AOS outcome (i.e., Milev et al., 2003) and provide greater regional resolution. Additionally, the current results coincide with prior GM abnormalities reported in COS relative to controls45, 2, 4 and spatially overlap with locations where the COS group as a whole had thinner cortex relative to controls3. Our findings indicate that participants with COS who remitted approximately three months (on average) after admission scan had defined areas of significantly thicker gray matter in left orbital-frontal, superior and middle temporal gyri, and bilateral angular and post-central parietal gyri. These results are associated with large effect sizes but are limited in terms of clinical predictive value (sensitivity under 40%, with prediction accuracy not much better than chance) as demonstrated by ROC and logistic regression results. Demographic variables such as age, IQ, sex, socio-economic status, and age of onset, and clinical variables such as admission functioning and scores on a measure of developmental delays (the ASQ) did not significantly differ between the groups.

Our results implicating frontal, temporal, and parietal involvement in remission are consistent with the schizophrenia imaging literature. Specifically, the left superior temporal gyrus is consistently found to be abnormal in schizophrenia46 and has been identified as having a role in auditory hallucinations47. Also, orbitofrontal abnormalities have been implicated in negative symptoms48–50. Bilateral frontal and temporal cortical thickness have also been found to positively relate to overall functioning in a sample of non-psychotic siblings of COS probands19. Thus, there appears to be accumulating evidence to suggest that pre-frontal and temporal cortices have an important role in illness, outcome and possibly functioning in general.

Relative to evidence supporting frontal and temporal involvement in schizophrenia, there is a dearth of information regarding parietal involvement46. However, results from a recently published COS study indicate that during adolescence superior parietal abnormalities normalize3. It is therefore possible that this normalization and/or treatment response may be linked by a common underlying mechanism. While the group of COS who remitted and the group of COS who did not remit did not significantly differ on mean cortical thickness, there was a statistical trend for increased overall gray matter thickness in the group who remitted. Total gray matter volume differences did not approach trend level significance, however. Because total gray matter volume is a function of thickness and surface area, this suggests that cortical surface area may be of interest to future studies of remission in relation to clinical follow-up status.

A major limitation to the current study is the individual variability in medication status, rendering medication effects on remission and cortical thickness too complicated to piece apart. However, because all of the participants were discharged on a tailored medication regimen, we speculate that this optimized medication combined with lengthy inpatient treatment contributed to our 29% remission rate. We also believe that that this remission rate overestimates good outcome frequency, and when participants are functioning with less support and increased demands, remission rates decline. Other limitations to this study include increased type I and type II error risks, and the less than six-month/non-sustained remission. Regarding the former, we were only powered to detect large effects, and thus have an increased type II error risk when assessing statistical significance for small and medium effect sizes associated with both cortical thickness and demographic variables. While our alpha level of 0.01 was liberal, a more conservative approach would have further reduced already relatively low power (for medium and small effect) and possibly eliminated our ability to detect large effects. Given the exploratory nature of the study, we thus decided to favor type I error risk over type II error risk when thresholding significance for cortical thickness analyses. Regarding remission duration criterion proposed by Andreasen and colleagues, the six-month time frame could not be established for our participants, as we do not typically hospitalize our participants for six or more months. As such, we technically do not meet criteria for the remission definition. However, this is not unprecedented, as a recent schizophrenia outcome study was also not able to meet the six month Working Group criterion but still found the amended remission definition useful in understanding outcome predictors51.

Circumscribed areas of gray matter in frontal, temporal, and parietal regions were significantly thicker for participants with COS who went on to remit approximately three months later (on average). Our results provide neuroanatomic correlates of the remission criteria set forth by Andreasen and colleagues and evidence for the localization of brain regions involved in resilience and/or treatment efficacy in schizophrenia. More attention is warranted to understand the relevance of gray matter correlates of clinical remission in COS.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Nicolson R, Rapoport JL. Childhood-onset schizophrenia: rare but worth studying. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;46(10):1418–1428. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00231-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thompson PM, Vidal C, Giedd JN, et al. Mapping adolescent brain change reveals dynamic wave of accelerated gray matter loss in very early-onset schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2001;98:11650–1165. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201243998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greenstein D, Lerch J, Shaw P, et al. Childhood-onset schizophrenia: cortical brain abnormalities as young adults. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47:1003–1012. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sporn AL, Greenstein DK, Gogtay N, et al. Progressive brain volume loss during adolescence in childhood-onset schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(12):2181–2189. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.12.2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rapoport JL, Addington AM, Frangou S. The neurodevelopmental model of schizophrenia: update. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10(5):434–449. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Milev P, Ho BC, Arndt S, Nopoulos P, Andreasen NC. Initial magnetic resonance imaging volumetric brain measurements and outcome in schizophrenia: a prospective longitudinal study with 5-year follow-up. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54(6):608–615. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00293-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prasad KMR, Sahni SD, Rohm BR, Keshavan MS. Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex morphology and short-term outcome in first-episode schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res: Neuroimaging. 2005;140(2):147–155. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2004.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeLisi LE, Stritzke P, Riordan H, et al. The timing of brain morphological changes in schizophrenia and their relationship to clinical outcome. Biol Psychiatry. 1992;31(3):241–254. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(92)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Haren NEM, Neeltje EM, Cahn W, et al. Brain volumes as predictor of outcome in recent-onset schizophrenia: a multi-center MRI study. Schizophr Res. 2003;64(1):41–52. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(03)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lieberman J, Chakos M, Wu H, et al. Longitudinal study of brain morphology in first episode schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;49(6):487–499. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01067-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeLisi LE, Sakuma M, Ge S, Kushner M. Association of brain structural change with the heterogeneous course of schizophrenia from early childhood through five years subsequent to a first hospitalization. Psychiatry Res: Neuroimaging. 1998;84(2–3):75–88. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4927(98)00047-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andreasen NC, Carpenter WT, Kane JM, Lasser RA, Marder SR, Weinberger DR. Remission in Schizophrenia: Proposed Criteria and Rationale for Consensus. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:441–449. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.3.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Os J, Drukker M, A Campo J, Meijer J, Bak M, Delespaul P. Validation of Remission Criteria for Schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:2000–2002. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.11.2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Emsley R, Oosthuizen PP, Kidd M, Koen L, Niehaus DJ, Turner HJ. Remission in first-episode psychosis: predictor variables and symptom improvement patterns. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(11):1707–1702. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Emsley R, Rabinowitz J, Medori R. Remission in early psychosis: Rates, predictors, and clinical and functional outcome correlates. Schizophr Res. 2007;89(1–3):129–139. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haro JM, Novick D, Suarez D, Alonso J, Lepine JP, Ratcliffe M. Remission and Relapse in the Outpatient Care of Schizophrenia: Three-year Results From the Schizophrenia Outpatient Health Outcomes Study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;26(6):571–578. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000246215.49271.b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Docherty JP, Bossie C, Lachaux B, et al. Patient-based and clinician-based support for the remission criteria in schizophrenia. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;22(1):51–55. doi: 10.1097/01.yic.0000224791.06159.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shaw P, Greenstein D, Lerch J, et al. Intellectual ability and cortical development in children and adolescents. Nature. 2006;440(7084):676–679. doi: 10.1038/nature04513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gogtay N, Greenstein D, Lenane M, et al. Cortical Brain Development in Nonpsychotic Siblings of Patients With Childhood-Onset Schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(7):772–780. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.7.772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumra S, Frazier JA, Jacobsen LK, et al. Childhood-onset schizophrenia. A double-blind clozapine-haloperidol comparison. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53(12):1090–1097. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830120020005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McKenna K, Gordon CT, Lenane M, Kaysen D, Fahey K, Rapoport JL. Looking for childhood-onset schizophrenia: the first 71 cases screened. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1994;33(5):636–44. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199406000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shaw P, Sporn AS, Gogtay N, et al. Childhood-Onset Schizophrenia: A Double-Blind, Randomized Clozapine-Olanzapine Comparison. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:721–730. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.7.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wechsler D. Manual for the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children—Revised. New York: Psychological Corporation; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wechsler D. Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children. 3. New York: Psychological Corporation; 1991. Manual. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale—Revised. New York: Psychological Corporation; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wechsler D. Manual for the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale—Third Edition. New York: Psychological Corporation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wechsler D. Weschler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence Manual. New York: Psychological Corporation; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hollingshead AB. Four-Factor Index for Social Status. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berument SK, Rutter M, Lord C, Pickles A, Bailey A. Autism Screening Questionnaire: Diagnostic Validity. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;175:444–451. doi: 10.1192/bjp.175.5.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shaffer D, Gould MS, Brasic J, et al. Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS) Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1983;40:1228–1231. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790100074010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Andreasen NC. Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) Iowa City: University of Iowa; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andreasen NC. Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) Iowa City: University of Iowa; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Castellanos FX, Geidd JN, Berquin PC, et al. Quantitative Brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Girls With Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(3):289–295. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.3.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sled JG, Zijdenbos AP, Evans AC. A nonparametric method for automatic correction of intensity nonuniformity in MRI data. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 1998;17(1):87–97. doi: 10.1109/42.668698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zijdenbos AP, Forghani R, Evans AC. Automatic “pipeline” analysis of 3-D MRI data for clinical trials: application to multiple sclerosis. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging. 2002;21(10):1280–1291. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2002.806283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.MacDonald D, Kabani N, Avis D, Evans AC. Automated 3-D Extraction of Inner and Outer Surfaces of Cerebral Cortex from MRI. NeuroImage. 2(3):340–356. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1999.0534. 20001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim JS, Singh V, Lee JK, et al. Automated 3-D extraction and evaluation of the inner and outer cortical surfaces using a Laplacian map and partial volume effect classification. Neuroimage. 2005;27(1):210–221. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Robbins S, Evans AC, Collins LD, Whitesides S, et al. Tuning and comparing spatial normalization methods. Med Image Analysis. 2004;8(3):311–323. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lerch JP, Evans AC. Cortical thickness analysis examined through power analysis and a population simulation. NeuroImage. 2005;24(1):163–173. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee JK, Lee JM, Kim JS, Kim IY, Evans AC, Kim SI. A novel quantitative cross-validation of different cortical surface reconstruction algorithms using MRI phantom. NeuroImage. 2006;31:572–584. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kabani N, LeGoualher G, MacDonald D, Evans AC. Measurement of Cortical Thickness Using an Automated 3-D Algorithm: A Validation Study. NeuroImage. 2001;13(2):375–380. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2000.0652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shaw P, Kabani NJ, Lerch JP, et al. Neurodevelopmental Trajectories of the Human Cerebral Cortex. J Neurosci. 2008;28:3586–3594. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5309-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lerch JP, Pruessner JC, Zijdenbos A, Hampel H, Teipel ST, Evans A. Focal decline of cortical thickness in alzheimer’s disease identified by computational Neuroanatomy. Cerebral Cortex. 2005;15(7):995–1001. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Collins DL, Holmes CJ, Peters TM, Evans AC. Automatic 3D model-based neuroanatomical segmentation. Human Brain Mapping. 1995;33:90–208. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rapoport JL, Giedd JN, Blumenthal J. Progressive cortical change during adolescence in childhood-onset schizophrenia: A longitudinal magnetic resonance imaging study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(7):649–654. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.7.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shenton ME, Dickey CC, Frumin M, McCarley RW. A review of MRI findings in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2001;49(1–2):1–52. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00163-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lawrie SM, Weinberger DR, Johnstone EC. Schizophrenia: From Neuroimaging to Neuroscience. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nakamura M, Nestor PG, McCarley RW. Altered orbitofrontal sulcogyral pattern in schizophrenia. Brain. 2007;130(3):693–707. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lacerda ALT, Hardan AY, Yorbik O, Vemulapali M, Prasad KM, Keshavan MS. Morphology of the orbitofrontal cortex in first-episode schizophrenia: Relationship with negative symptomatology. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2007;31(2):510–516. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2006.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gur RE, Cowell PE, Latshaw A, et al. Reduced Dorsal and Orbital Prefrontal Gray Matter Volumes in Schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:761–768. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.8.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lauronen E, Miettunen J, Veijola J, Karhu M, Jones PB, Isohanni M. Outcome and its predictors in schizophrenia within the Northern Finland 1966 Birth Cohort. Eur Psychiatry. 2007;22(2):129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]