Abstract

Retention index (RI) is useful for metabolite identification. However, when RI is integrated with mass spectral similarity for metabolite identification, many controversial RI threshold setup are reported in literatures. In this study, a large scale test dataset of 5844 compounds with both mass spectra and RI information were created from National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) repetitive mass spectra (MS) and RI library. Three MS similarity measures: NIST composite measure, the real part of Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT.R) and the detail of Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT.D) were used to investigate the accuracy of compound identification using the test dataset. To imitate real identification experiments, NIST MS main library was employed as reference library and the test dataset was used as search data. Our study shows that the optimal RI thresholds are 22, 15, and 15 i.u. for the NIST composite, DFT.R and DWT.D measures, respectively, when the RI and mass spectral similarity are integrated for compound identification. Compared to the mass spectrum matching, using both RI and mass spectral matching can improve the identification accuracy by 1.7%, 3.5%, and 3.5% for the three mass spectral similarity measures, respectively. It is concluded that the improvement of RI matching for compound identification heavily depends on the method of MS spectral similarity measure and the accuracy of RI data.

Keywords: Retention index threshold, Metabolite identification, Mass spectral similarity measure

1. Introduction

Gas chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry (GC/MS) is one of the most widely used analytical tools for metabolomics study, in which the compound identification is done by comparison of the experimental mass spectra (MS) data with well-collected reference spectral library. In spite of many commercial and academic spectral libraries [1, 2] and various measures of mass spectral similarity [3, 4] are available in recent decades, the existing identification methods generate a high rate of false-positive and false-negative identifications. At the American Society for Mass Spectrometry (ASMS) conference 2009, a survey among 600 participants revealed that metabolite identification is still the main bottleneck in analysis of metabolomics data [5].

Metabolomics Standards Initiative (MSI) has suggested that at least two independent data relative to an authentic compound analyzed under identical experimental condition need to be acquired [6]. In the GC/MS based metabolomics study, retention index (RI) [7, 8] in conjunction with the MS information is widely accepted as useful method for metabolite identification.

In “targeted” metabolomics, many successful metabolite identification applications using RI information have been reported [9, 10]. The global metabolomics studies, all metabolites present in a given sample need to be detected, regardless of their chemical class or character. In this way, a large MS library such as National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) MS library is needed. However, significant challenges remain in compound identification using RI in this field.

Two main problems prevent the wide usage of the RI data for global metabolomics. The first one is the incompleteness of RI data. Even though several RI libraries have been developed in recent years [11–13, 9], the severe deficiency of RI data makes the extensive applications impossible. For example, only 21,847 compounds have RI data in NIST 2008 MS library while 192,108 compounds have mass spectra. Even though Quantitative Structure Retention Relationships (QSRR) [14, 15] can be used to compensate the shortage of the RI data, most of the literature reported works only focus on the RI prediction of a small number of metabolites [16, 17], a few studies focused on large scale prediction of compound retention index. Stein et al. developed a RI prediction model based on chemical group contribution and released the predicted results with NIST MS library [18]. However, the accuracy of such a prediction model is not widely validated and therefore, the predicted results may be insufficient for metabolite identification. Mihaleva et al. used genetic algorithm (GA) coupled with support vector regression (SVR) to predict RI data, but the predicted RI data were not released and cannot be used by other laboratories for comparison [19]. The second problem is that the RI value of a compound is still affected by many experimental conditions. Such as the stationary phase of GC column [20, 21], column temperature [22] and intra and inter-laboratory variations [23].

Consequently, RI deviation window or threshold needs to be predefined in order to aid metabolite identification. A compound is considered as false-positive identification if the difference between experimental RI value and reference RI value is larger than the predefined threshold. For instance, the AMDIS software also provides RI filter interface as option. RI is also directly integrated with MS similarity measure to determine a composite score [24]. Consequently this may be a better way to improve true positive rate by changing the similarity score metric. However, the existing literatures reports are conflict to each other in determining the size of RI variation window. Software Massfinder [25] suggests 10 index unit (i.u.) variation window for a semi non-polar DB-5 column while Hiller et al. [24] set the threshold to a value between 2 and 10 i.u. In the MODELKEY project, the compounds with 20 i.u. variation were considered as true identification [26]. Strehmel et al. [27] suggested to use relative threshold.

Currently, there is no method developed to optimize the RI threshold and verify the identification ability of existing RI library using a large test dataset. In this work, a large scale test dataset was created from the existing NIST MS and RI library and three MS similarity measures were integrated with RI matching for compound identification. The three mass spectral similarity measures are: National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) spectral composite similarity measure [4], discrete Fourier transform (DFT) and discrete wavelet transform (DWT) [28]. The optimal RI threshold is explored in conjunction with three similarity measures using the test dataset.

All the methods were performed using the software Matlab R2008b. For the ease of description, the terms spectrum, metabolite and compound is used interchangeably throughout this paper.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Mass spectral reference library and test dataset with retention index

The NIST MS library has two electron ionization (EI) mass spectral libraries: main library (mainlib) and repetitive library (replib). All mass spectra (the main library contains 163,198 mass spectra and repetitive library contains 28,234 mass spectra) of the compounds are extracted from NIST MS library. To imitate the real identification experiments, the main library is used as reference MS library while the replicate spectra are used as test spectra dataset. A true identification can be recognized by comparing the Chemical Abstract Service (CAS) registry number of the test spectrum and the spectrum of the reference MS library.

We also extracted the RI data of the compounds with CAS numbers from the NIST RI library. The NIST RI library grouped the column stationary phase into three categories: standard non-polar (typical column is DB-1, 100% dimethylpolysiloxane), semi non-polar DB-5 ((5%-phenyl)-methylpolysiloxane, 95% dimethyl) and standard polar column (DB-WAX, polyethylene glycol (PEG)). In this study, we only focus on the semi non-polar column. One semi non-polar column RI value of a compound is randomly selected as the experimental RI value for the test dataset. Since the collected RI data is much smaller than the repetitive mass spectra data, only those compounds with RI information are chosen to create test dataset. Finally, a test dataset containing 5844 mass spectra with experimental RI value is created.

2.2. Mechanism of mass spectral library search and RI application

Mass spectral library search algorithms identify unknown compounds by matching their mass spectra with the mass spectra in reference library. In most cases, the algorithms find and rank reference compounds by their spectral similarity to the unknown compound. The higher the spectral similarity, the higher confidence in the identification. When the compound with high rank is not true identification, RI matching can be integrated with MS matching to decrease the rate of false identification. A simple RI comparison method is taken in this study as follows:

| (1) |

where Iexp is the RI value in test dataset, which represents experimental RI value, Iref is the median of the RI values of a candidate in the reference library. When NIST predicted RI is used for comparison, Iref is NIST predicted RI value of candidate compound. _I is RI threshold need to be setup. If the difference between experimental and reference RI is smaller than the threshold _Ithe identification is considered as a true identification. Otherwise, the identification is discarded and the process is repeated to the next compound based on its rank of spectrum similarity. In case a candidate compound matched by mass spectral matching does not have RI information in the RI reference library, the RI matching will not be performed and the candidate compound is preserved as a true identification.

2.3. Performance measurement

To measure the performance of compound identification via integrating mass spectral matching and RI matching, the accuracy, precision and recall are calculated. The accuracy is the proportion of the spectra identified correctly in query data. In other words, if the unknown and reference spectra have the same CAS number, the compound is considered as correct matching. Otherwise, the match is incorrect. Therefore, the accuracy of identification can be calculated by:

| (2) |

A threshold of the spectrum similarity is usually used to determine whether an identification is acceptable. If the similarity of a query spectrum and a reference spectrum is higher than the threshold, the identified compound is considered as positive identification. Otherwise, it is discarded as negative identification. The precision is the proportion of predicted positive cases that are correctly real positives and the recall is the proportion of real positive cases that are correctly predicted positive. The precision and recall are calculated as follows in this paper:

| (3) |

| (4) |

where TP is the number of matched spectrum pairs having the same compound CAS number, FP is the number of matched spectrum pairs having different compound CAS numbers, FN is the number of unmatched spectrum pairs having the same compound CAS number. For every threshold, the precision and recall can be calculated and precision–recall plot can be drawn by many thresholds.

3. Theoretical basis

3.1. Retention index

Two kinds of retention index systems, Kovats and Linear RI, use homologous alkane series as reference compounds [7, 8], where the retention index of an alkane with n carbons is defined as 100n. The Kovats RI is measured under isothermal condition and the Linear RI is measured under temperature-programmed condition. The Kovats RI and the Linear RI are calculated as follows:

| (5) |

| (6) |

where I and IT are the Kovats RI and Linear RI, respectively, tR(s) is the retention time of the target compound that elutes off the GC column between two adjacent n-alkane reference compounds with carbon numbers z and z + 1, respectively, tR(z) is the retention time of the alkane with z carbon atoms, and tR(z+1) is the retention time of the alkane with z + 1 carbon atoms.

3.2. Mass spectral similarity measures

Let two signals X = (x1, x2, …, xn) and Y = (y1, y2, …, yn) be the unknown and reference mass spectra, respectively. We only consider NIST similarity measure, Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT) and Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT) similarity measures in this paper.

Dot-product (cosine correlation)

Dot product is a measure of correlation between two signals using the cosine value of angle. The definition is:

| (7) |

where k = 1, 2, …, nsince all the intensities are non-negative, the similarity value is always greater than or equal to zero.

NIST composite similarity measure

Stein and Scott proposed a similarity measure of cosine correlation with weighted intensities [5]. Sw can be calculated by

| (8) |

where are the weighted intensities. is:

| (9) |

where zk is the m/z value of kth intensity. a and b represent the contribution of the m/z value and the peak intensity, respectively. Stein and Scott suggested the optimal value is taken as a = 3 and b = 0.5.

Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT) similarity measure

The DFT is a specific kind of discrete transform, which transforms the original time domain signals into a series of frequency domain signals. The original signal X = (x1, x2, …, xn) is transformed into by DFT according to the following formula:

| (10) |

where i is the imaginary unit. Eq. (10) can be converted into the following formula:

| (11) |

The real part of a signal X can be calculated by the following equation:

| (12) |

In this study, we only focus on the real part on DFT (DFT.R) of the signal X to create mass spectra similarity measure.

Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT) similarity measure

The DWT is a wavelet transform that converts a discrete time domain signal into a time-frequency domain signal. When a signal passes through a low-pass filter and a high-pass filter, two subsets of signals are formed: approximation and detail. The approximation and detail are defined as follows:

| (13) |

| (14) |

where g and h are low-pass and high-pass filters, respectively. The final approximation and detail DWTs of a signal X are converted as follows:

| (15) |

The detail DWTs (DWT.D) are used in this study to create similarity measure. In-depth theoretical background on these two similarity measures can be found in literature [28].

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Performance of spectral similarity measures

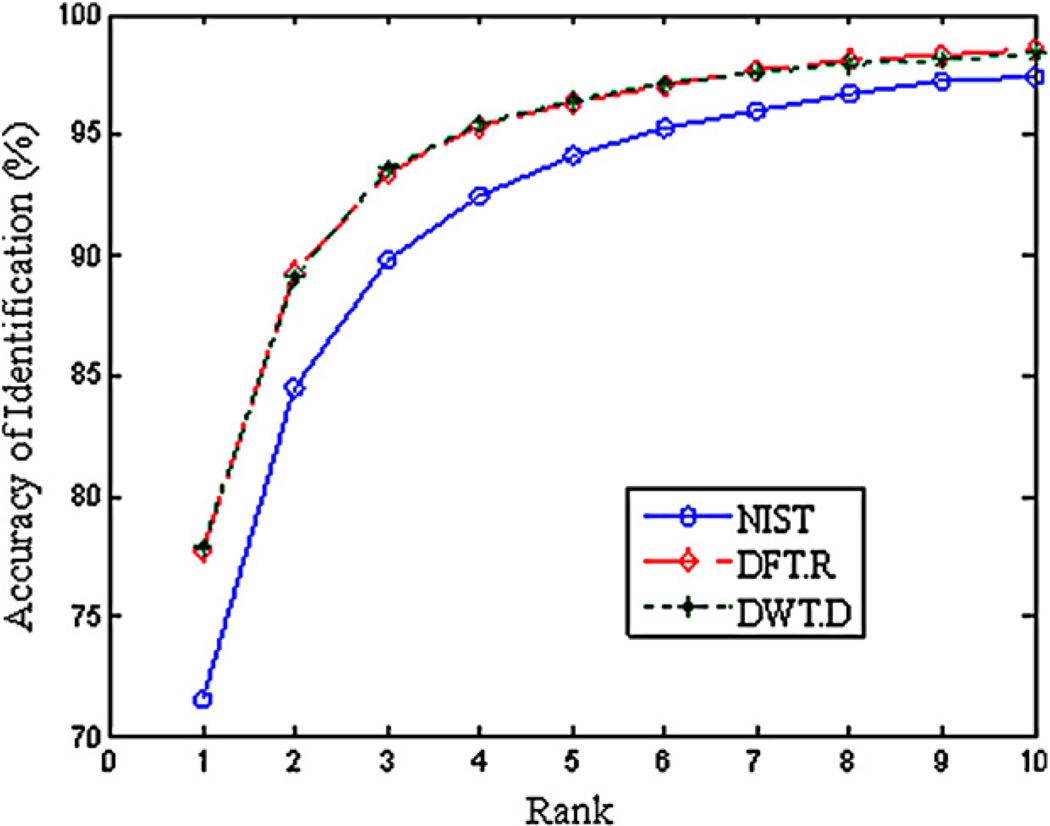

The identification results, expressed as percent correct identification as a function of the spectral similarity rank in the hit list, for the first three ranks of three similarity measures are given in Table 1. Fig. 1 depicts the relation of identification accuracy and the rank of spectral similarity measures. Since the reference MS library is the real NIST2008 library, the results are quite reliable. If only considering rank 1 results, NIST composite measure can only identify 71.5% of compounds. DFT.R and DWT.D achieve similar results with an accuracy of 77.7% and 77.9%, respectively. Taking into account ranks 1–3, the accuracy of NIST composite measure increased by approximately 18%, while the identification accuracy only increased by about 16% for DFT.R and DWT.D measures. Overall, DFT.R and DWT.D measures achieve much better performance than the NIST composite measure. The increased identification accuracy in DFT and DWT may accredit that both DFT and DWT are noise removal algorithms, which may remove a certain degree of noise from the original spectrum and improve the results of identification. This can also explain that these two spectral similarity measures achieve almost identical identification results.

Table 1.

Accuracy (%) of compound identication using the three mass spectral similarity measures.

| Similarity measure | Accuracy at rank (%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Rank 1 | Rank 1 + 2 | Rank 1 + 2 + 3 | |

| NIST | 71.5 | 84.4 | 89.8 |

| DFT.R | 77.7 | 89.2 | 93.4 |

| DWT.D | 77.9 | 89 | 93.6 |

Fig. 1.

Search accuracy–rank position plot for NIST composite, DFT.R and DWT.D measures, respectively. All 5844 spectra in the test dataset were used as query spectra and the NIST main MS library was used as the reference library. Each point gives the percentage of the number of spectra matched correctly among all spectra queried.

4.2. The ability of using RI separates true identification from false identification

To measure the ability of existing RI data in separating true identification from false identification, two group data were created from the top 30 spectral matching results based on NIST composite similarity measure: if two spectra have the same CAS number, the identified compound is recorded into a true identification group, otherwise, the identified compound is recorded to a false identification group. The difference between experimental and reference RI is calculated if those compounds’ reference RI are available. Fig. 2(A) shows two distributions of RI deviation. It can be seen that the distribution of true identification group is much narrower than the false identification group, demonstrating that using RI is able to separate some of the true identifications from the false identifications, i.e., reducing the rate of false identification. For example, red lines in Fig. 2 refer to RI deviation window (threshold) 90 i.u. To show the RI separation ability more clearly, Fig. 2(B) is empirical cumulative distribution of the absolute difference for these two groups. The compounds on the left of the red line are kept as true identification, while those on the right will be discarded and the RI match moves to the candidate compounds with the next highest spectral similarity rank for matching. By doing so, 80% of true identifications are confirmed and about 68% of the false identifications will re-match in the next rank. The proportion of the confirmed compounds by RI matching to the re-matching compounds will vary with the size of RI threshold.

Fig. 2.

The effects of using retention index threshold as a filter to separate the true identifications and the false identifications generated by mass spectral matching using the NIST composite spectral similarity measure. (A) The distribution curve of the difference between experimental and reference RI on the true identification and false identification groups. (B) Empirical cumulative distribution of the absolute difference between experimental and reference I on two groups. The red lines in (A) and (B) represent RI threshold. (C) The reference RI data are NIST predicted RI. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of the article.)

NIST predicted RI data also were used as reference RI to create Fig. 2(C). Obviously, NIST predicted RI data still has ability to separate the true identifications from the false identifications based on NIST composite similarity measure, even with a lower precision a large RI threshold.

4.3. The performance of identification by using RI

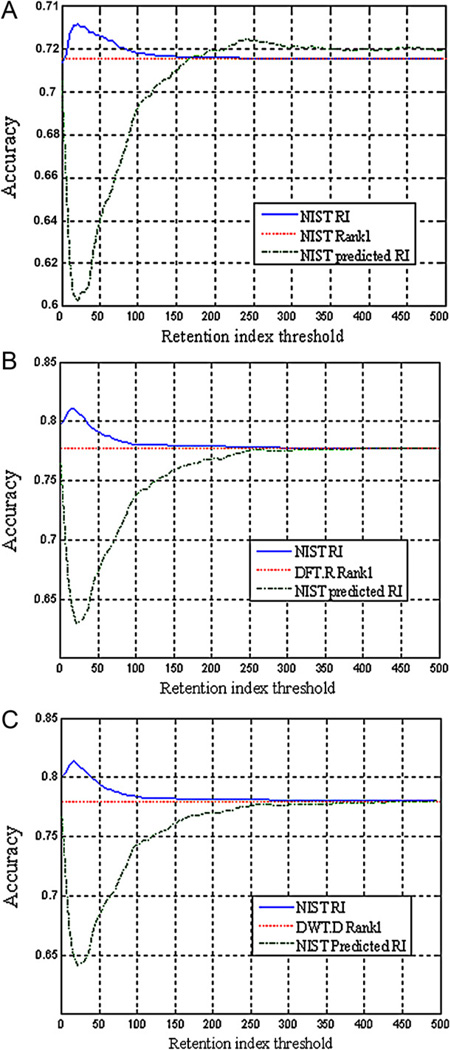

The performance of compound identification using RI matching in conjunction with mass spectral matching depends on two factors: the accuracy of RI values and the spectral similarity measure. The optimal RI threshold is determined by these two factors. If the accuracy of RI values is lower, the RI threshold needs to be set a large value and vice versa. Furthermore, RI threshold needs to be adjusted for different spectral similarity measures. In order to investigate contribution of RI matching to compound identification, the threshold of RI variation was set from 1 to 500 i.u. for each of the three spectral similarity measures. The real experimental RI data (median value of each compound from NIST RI library) and NIST predicted RI were used as reference RI for comparison. Fig. 3(A)–(C) depicts the identification results using the spectral similarity measure of NIST composite, DFT.R and DWT.D, respectively. For the RI data in the NIST RI reference library, the accuracy of identification initially increases with increase of retention index threshold. After the retention index threshold reaches to an optimal value, the accuracy begins to decrease. When the threshold is larger than a certain value, RI matching cannot improve the identification results of MS matching. The optimal RI thresholds for the three MS spectral measures are 22, 15, and 15 i.u. respectively, and the improvements of identification accuracy rate are 1.7%, 3.5%, and 3.5% for NIST, DFT.R and DWT.D similarity measures, respectively. If providing more RI data, more improvement in identification results would be achieved. It is interested that the use of NIST predicted RI values actually decreases the identification accuracy when the RI threshold was small in all the three spectral similarity measures. It only slightly improves the identification accuracy when the NIST composite spectral similarity is used and the RI threshold is set to larger than 175 i.u. The identification accuracy reaches to the maxima at the RI threshold of 241 i.u., where the identification accuracy is improved about 0.93%. Considering that most of the compounds have NIST predicted RI value (about 100,000 compounds), it is not easy to improve the identification results based on NIST predicted RI anymore (Table 2).

Fig. 3.

Retention index threshold–accuracy of compound identification using different spectral similarity measures. (A) NIST composite mass spectral similarity measure; (B) DFT.R mass spectral similarity measure; (C) DWT.D mass spectral similarity measure. The red line is the identification accuracy of the true compound was ranked as the top compound candidate, the blue line is that NIST RI library is used as the reference RI, while the green line is that the NIST predicted RI data are used as the reference RI. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of the article.)

Table 2.

The performance of integrating RI information and the three MS spectral similarity measures for compound identification at the optimal RI threshold.

| Reference RI | Similarity measure |

Rank 1 | Optimal accuracy |

Optimal RI threshold |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NIST RI library | NIST | 71.5% | 73.2% | 22 |

| DFT.R | 77.7% | 81.2% | 15 | |

| DWT.D | 77.9% | 81.4% | 15 | |

| NIST predicted RI | NIST | 71.5% | 72.4% | 241 |

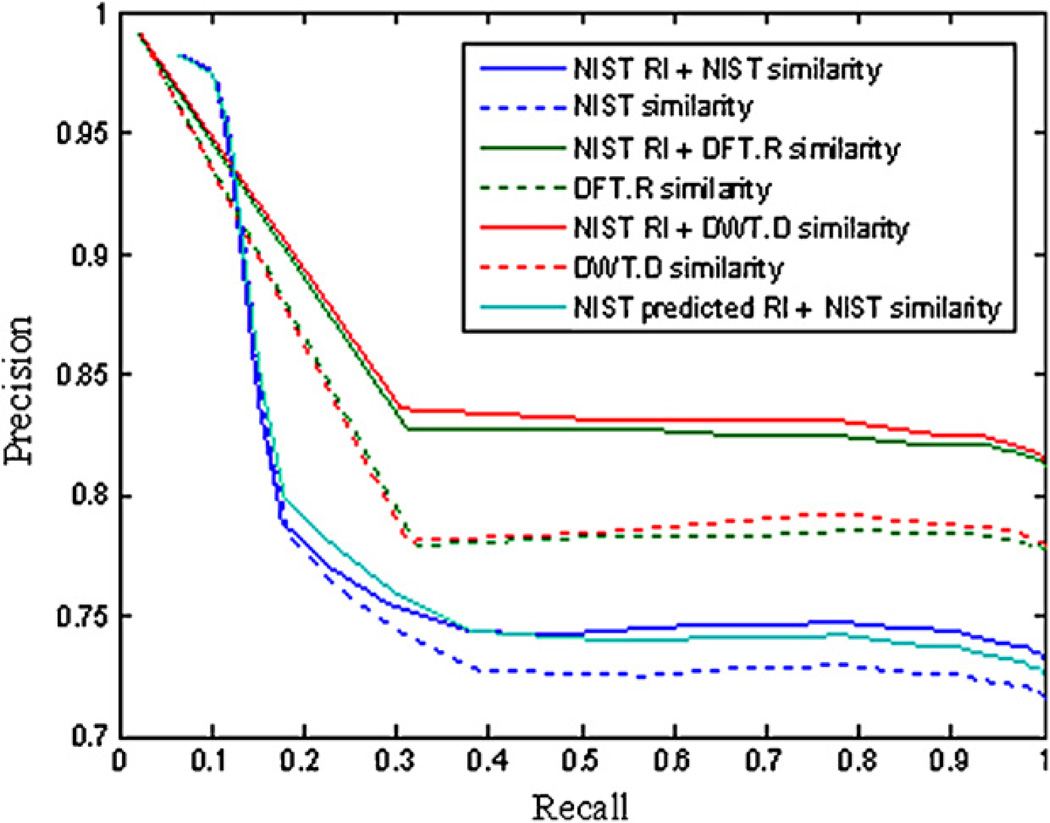

The precision–recall plot is depicted according to the different threshold of the spectral similarity between 0 and 1. The NIST RI library was used as reference RI to aid MS identification following the mass spectral matching using three MS similarity measures. The RI threshold was set at the optimal values, 22, 15, and 15 i.u. for NIST composite, DFT.R and DWT.R measures, respectively. To compare the identification results using NIST RI library, the identification results of the spectral similarity ranked as the top hit by three similarity measures are displayed in Fig. 4. The results of using NIST predicted RI and NIST spectral similarity measure are also plotted. It can be seen that the DFT.R and DWT.D measures perform better than the NIST composite similarity measure. The use the RI matching can significantly improve the identification precision of mass spectral matching calculated by DFT.R and DWT.D, and the identification results of DWT.D similarity is better than the DFT.R similarity. The RI from NIST library can improve the identified results of three MS similarity measures while the NIST predicted RI only slightly improves the identification results when the NIST composite similarity is used.

Fig. 4.

Relationship of precision and recall in compound identification by integrating RI data with three mass spectral similarity measures.

5. Conclusions

A large scale test dataset of 5844 compounds with both the mass spectra and RI information are created from NIST repetitive MS and RI library. To imitate the real identification experiment, NIST MS main library is employed as reference library. Three MS similarity measures: NIST composite, DFT.R and DWT.D are used to investigate the accuracy of compound identification using the test dataset. NIST composite spectral measure reaches a 71.5% of identification accuracy for the top ranked candidates while DFT.R and DWT.D achieve similar results: 77.7% and 77.9%, respectively. When the RI information of the NIST RI reference library is integrated with MS matching for compound identification, the optimal RI thresholds are 22, 15, and 15 i.u. for the NIST composite, DFT.R and DWT.D measures, respectively and the identification accuracy is improved by 1.7%, 3.5%, and 3.5%, respectively. The NIST predicted RI can improve the identification accuracy by 0.93% when the optimal RI threshold is set as 241 i.u and the maximal improvement of the identification is 0.93%. Currently, most RI research is based on NIST similarity measure. The optimal RI threshold obtained in this research is larger than previous study. Considering the large test dataset employed, the obtained RI threshold is potential useful for further study.

This study shows that RI prediction accuracy, RI threshold setup and MS similarity measure all play role to the final identification results when the RI information is integrated with MS similarity measures for compound identification. The improvement of RI matching for compound identification heavily depends on the method of MS similarity measure. The NIST RI library can be used to improve the accuracy of compound identification for all three spectral similarity measures. However, the optimal RI threshold is spectral similarity measure dependent.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grant 1RO1GM087735 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) within the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Natural Science Foundation of China under grant nos. 61032007 and 60803107, and Provincial Natural Science Research Program of Higher Education Institutions of Anhui Province under grant no. KJ2012A005.

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chroma.2012.06.036.

References

- 1.Horai H, Arita M, Kanaya S, Nihei Y, Ikeda T, Suwa K, Ojima Y, Tanaka K, Tanaka S, Aoshima K, Oda Y, Kakazu Y, Kusano M, Tohge T, Matsuda F, Sawada Y, Hirai MY, Nakanishi H, Ikeda K, Akimoto N, Maoka T, Takahashi H, Ara T, Sakurai N, Suzuki H, Shibata D, Neumann S, Iida T, Tanaka K, Funatsu K, Matsuura F, Soga T, Taguchi R, Saito K, Nishioka T. J. Mass Spectrom. 2010;45:703. doi: 10.1002/jms.1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schauer N, Steinhauser D, Strelkov S, Schomburg D, Allison G, Moritz T, Lundgren K, Roessner-Tunali U, Forbes MG, Willmitzer L, Fernie AR, Kopka J. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:1332. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stein SE. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 1994;5:316. doi: 10.1016/1044-0305(94)85022-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stein SE, Scott DR. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 1994;5:859. doi: 10.1016/1044-0305(94)87009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neumann S, Bocker S. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2010;398:2779. doi: 10.1007/s00216-010-4142-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sumner LW, Amberg A, Barrett D, Beale MH, Beger R, Daykin CA, Fan TWM, Fiehn O, Goodacre R, Griffin JL, Hankemeier T, Hardy N, Harnly J, Higashi R, Kopka J, Lane AN, Lindon JC, Marriott P, Nicholls AW, Reily MD, Thaden JJ, Viant MR. Metabolomics. 2007;3:211. doi: 10.1007/s11306-007-0082-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kovats E. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1958;41:1915. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dool Hvd, Kratz PD. J. Chromatogr. 1963;11:463. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)80947-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bianchi F, Careri M, Mangia A, Musci M. J. Sep. Sci. 2007;30:563. doi: 10.1002/jssc.200600393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mondello L, Salvatore A, Tranchida PQ, Casilli A, Dugo P, Dugo G. J. Chromatogr. A. 2008;1186:430. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2007.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Babushok VI, Linstrom PJ, Reed JJ, Zenkevich IG, Brown RL, Mallard WG, Stein SE. J. Chromatogr. A. 2007;1157:414. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2007.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kind T, Wohlgemuth G, Lee DY, Lu Y, Palazoglu M, Shahbaz S, Fiehn O. Anal. Chem. 2009;81:10038. doi: 10.1021/ac9019522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richmond R. J. Chromatogr. A. 1997;758:319. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heberger K. J. Chromatogr. A. 2007;1158:273. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2007.03.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaliszan R. Chem. Rev. 2007;107:3212. doi: 10.1021/cr068412z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fatemi MH, Baher E, Ghorbanzade’h M. J. Sep. Sci. 2009;32:4133. doi: 10.1002/jssc.200900373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katritzky AR, Chen K, Maran U, Carlson DA. Anal. Chem. 2000;72:101. doi: 10.1021/ac990800w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stein SE, Babushok VI, Brown RL, Linstrom PJ. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2007;47:975. doi: 10.1021/ci600548y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mihaleva VV, Verhoeven HA, de Vos RCH, Hall RD, van Ham RCHJ. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:787. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poole CF, Kollie TO, Poole SK. Chromatographia. 1992;34:281. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang J, Fang AQ, Wang B, Kim SH, Bogdanov B, Zhou ZX, McClain C, Zhang X. J. Chromatogr. A. 2011;1218:6522. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2011.07.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gorgenyi M, Dewulf J, Van Langenhove H. J. Chromatogr. A. 2006;1137:84. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2006.09.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zenkevich IG, Babushok VI, Linstrom PJ, White E, Stein SE. J. Chromatogr. A. 2009;1216:6651. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2009.07.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hiller K, Hangebrauk J, Jager C, Spura J, Schreiber K, Schomburg D. Anal. Chem. 2009;81:3429. doi: 10.1021/ac802689c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sparkman OD. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2007;18:1137. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weiss JM, Hamers T, Thomas KV, van der Linden S, Leonards PEG, Lamoree MH. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2009;394:1385. doi: 10.1007/s00216-009-2807-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kopka J, Strehmel N, Hummel J, Erban A, Strassburg K. J. Chromatogr. B. 2008;871:182. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2008.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koo I, Zhang X, Kim S. Anal. Chem. 2011;83:5631. doi: 10.1021/ac200740w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.