Abstract

Objectives:

The objectives of this study were to explore the perception of body weight among students in schools in Jeddah City and identify the main determinants of self-perceived obesity, weight management goals and practices.

Material and Methods:

Data were collected from a sample of Saudi school children of 42 boys’ and 42 girls’ schools in Jeddah city during the month of April 2000. Personal interviews were conducted to collect data on socio-demographic factors, food choices, perception of body weight, weight management goals and weight management practices, as well as the actual measurement of weight and height. Students were asked about their perception of their body weight [responses included: very underweight (thin), slightly underweight, about right weight, slightly overweight and grossly overweight (obese)]. Proportion, prevalence and 95% confidence intervals were calculated. Multiple logistic regression models were fitted to calculate the adjusted odds ratio (OR) for an attempt to lose weight and weight management practices.

Results:

The distribution of self-perception of body size was nearly similar to the measured body mass index (BMI) classification except for the overweight students, where 21.3% perceived themselves, as slightly overweight and 5.5% as very overweight although 13.4% were actually overweight and 13.5% were obese by BMI standards. Approximately half the students took at least 3 pieces of fruit or fruit juice servings, and a third ate at least 4 vegetable servings per day. A third of the students managed to lose weight. This coincides with the proportion of those actually overweight and obese. Around 28.0% of the students ate less food, fat or calories, 31.0% took exercise and 17.6% were engaged in vigorous exercise to lose weight or prevent weight gain. Staying for at least 24 hours without food which is a potentially harmful means of weight control was practiced by 10.0% of students. Females were less likely than males to be overweight and obese but more likely to perceive themselves as grossly overweight and more likely to try to lose weight. Factors associated with efforts to lose weight by eating less fat or fewer calories were older age, high social class, being actually obese and perceiving oneself as being obese. Staying for at least 24 hours without eating was mainly practiced by females, older age groups, and the actually obese. Exercise was done mainly by the older age groups, those with educated and highly educated mothers, obese and perceiving oneself as being obese. Vigorous exercise was mainly performed by males, younger age groups, taking < 3 pieces of fruit or fruit juice servings per day, eating < 4 vegetable servings per day, and those perceiving themselves as obese.

Conclusion:

Overweight and obesity are prevalent among our youth and not all obese have a correct image of their body size. Highly recommended are intervention programs of education on nutrition starting in childhood through school age to promote and ensure healthy food choices, improve student's awareness of ideal body size and clinical obesity, encourage physical exercise but discourage potentially harmful weight control measures.

Keywords: Overweight, perceived obesity, diet, physical activity, weight management, children, adolescents

INTRODUCTION

Obesity is associated with increased risk of morbidity and mortality1 related to a variety of diseases such as coronary heart diseases,2–4 hypertension,5,6 non-insulin dependent diabetes7–9 and some cancers.10 It appears to be traceable from childhood into adulthood. Overweight during late adolescence is most strongly associated with increased risk of overweight and obesity in adulthhod.11

Adolescence is a time of high nutritional requirements; nonetheless dieting by teenage girls in an effort to control body weight is well-documented.12 In fact, obesity phobia is so pervasive among female adolescents that it has been described as ‘a normative discontent’.13 This desire for thinness by girls as young as 9 years,14 has its origins in the ‘narrow hipped, thin ankle’ idea of female beauty depicted by society.15 By the age of nine, girls and boys already differ in their body shape and aspirations. Initiatives to reduce obesity should acknowledge these early strongly held views by the different genders or risk the promotion of unwarranted pursuit of thinness by girls.14

The consequences of restrained eating during the teenage years have raised many concerns. A lower intake of all micronutrients has been reported among dieting British girls aged 16-17 years compared with girls who were not dieting.16 Furthermore, in a 12-month follow-up study of 176 London schoolgirls aged 15 years, Patton et al17 reported that the relative risk of ‘dieters’ developing an eating disorder was eight times that of ‘non-dieters’. The effects of dieting on cognitive functioning have also been noted.18

Recommendations for the long-term treatment and prevention of obesity in adults include multi-component interventions that combine a healthy diet and exercise with behavior modifications designed to facilitate the maintenance of these lifestyle changes throughout life. The United States’ objectives for healthy dietary behavior and physical activity include increased consumption of fruits and vegetables, reduced consumption of dietary fat, performance of at least 30 minutes of moderate physical activity most days of the week, participation in vigorous physical activity that promotes the development of cardio-respiratory fitness for 20 or more minutes at least 3 days per week, and regular performance of physical activities that enhance and maintain muscular strength and flexibility.19,20 Therefore, declining physical activity, particularly incidental activity, is believed to be an important contributor to the burgeoning prevalence of obesity in Western nations.21 Increasing physical activity is therefore, viewed as an important component of attempts to control weight.21,22 Physical activity has been shown to complement dietary restriction or changes in diet composition undertaken for weight reduction.23 Importantly, physical activity aids the preservation of lean body tissue usually lost during dietary restriction, while the additional elevation of energy expenditure further enhances negative energy balance.22 Although weight loss attributable to increased physical activity may be small, it has been repeatedly shown to play an important role in the maintenance of weight loss. In addition, there is evidence to suggest that physical activity is important in preventing weight gain over time.24

Reduction of the disease burden of obesity in a population depends on identifying the risk factors that influence body weight. Obesity is an end result of many factors. The most important are the life-style factors and cultural perception of the ideal body weight. Food choice and physical activity assisted by behavior modification designed to facilitate these life style practices are believed to be the principal contributors to the prevalence of obesity.25–27 The cultural norms delineate the predominant perception of ideal body weight. Western culture has a prevailing perception that low body weight is attractive.28 In the past, overweight and obesity were perceived in Arab countries as signs of good health, wealth and authority. However, with advancing education, development of health care services and improvement of health awareness, this view has changed and people have become more concerned about being overweight. Considerably high proportions of Saudi youth that is, approximately 27.5% boys and 28.0% girls, were observed to be overweight and obese. No studies exploring the perception of body weight in Saudi Arabian adolescents have been done, to our knowledge, and the few available studies concentrate on adult women only.29 The objectives of this study were to explore the perception of body weight among school students in Jeddah city, and to identify the main determinants of perceived obesity. There is also a description of the demographic distribution of selected weight management goals and practices among Saudi students and the types of food choices associated with these weight management goals and practices.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Study population

Jeddah city, with a population of 2.1 million, is one of the largest cities in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. The last available Saudi population census, in the year 1993 indicates that it has a total of 692 government schools and 327 private schools, around half of which are for boys and half for girls.

Sample Selection

The sample of 42 boys’ schools and 42 girls’ schools was selected by stratified sampling technique with proportional allocation to type of school (government or private) and educational level during the month of April 2000. A large sample size was considered (2860 students) with an equal sample distribution in both sexes to ensure that the fourth year medical students were given enough exposure on how to conduct a field survey (interviewers). However, the prevalence of obesity by self-perception was unknown in our study population. One class from each educational level starting from the fourth grade upward was randomly chosen in the selected schools. All students in the selected class present during the study period were considered. Only students of Saudi nationality were considered for this study. A participation rate of around 99.0% was attained. Approval for the conduct of the field survey was obtained from the Ministry of Education and The General Presidency for Girl's Education in the Jeddah region. These letters of approval were given to each school principal to ensure cooperation.

Data Collection

Data were collected during April 2000 by 220 male and female fourth year medical students trained in interviewing skills, and directly supervised by the medical staff. The month prior to the data collection was spent on questionnaire development and a pilot study, and the correction of the questionnaire. Data were collected by personal interviews using a structured questionnaire, which included information on socio-demographic factors, food choices, perception of body weight, weight management goals and weight management practices, as well as, direct measurements of weight and height.

Although both variables were collected in the study, mother's rather than the father's educational level was used since mother's education was better for ranking (more variability) between children in the different social classes. They were classified into low (no school, primary and attended intermediate school), middle (completed intermediate and secondary schools) and high (attended or completed college and higher). Type of school was taken as a proxy measure for the social class status, since it is well known in Saudi society that private schools are mainly attended by the higher social class and governmental schools by the lower social class, and since only Saudis were selected for the study, it was assumed that this would be valid to a large extent.

Consumption of fruits and vegetables was measured using five separate questions on the form. It elicited information on the number of times the students had eaten fruit or drunk fruit juice, eaten green salad, carrots and other vegetables (excluding potatoes) during the last 7 days. Responses included: 0 times, 1-3 times per week, 4-6 times per week, one time per day, 2 times per day, 3 times per day and 4 or more times per day. Then both variables were classified into two levels according to their frequency distributions to minimize any misclassification. Students also were asked about their perception of their body weight [responses included: very underweight (thin), slightly underweight, about right weight, slightly overweight and grossly overweight (obese)]. The very underweight and slightly underweight categories were combined and seen as comparable to measured body mass index variable. This scale of five categories response options is mutually exclusive and inclusive of all possible responses on weight perception.

Weight was measured without shoes using Seca (model 777) personal scale to the nearest 0.1 kg and height was taken without shoes using the standard measuring tape to nearest 0.1 cm. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as the measured weight in kg/(measured height in m)2. The measured body mass indexes were classified into 5 categories according to age and gender thus: thin (< 5th percentile), underweight (≥ 5th percentile - < 15th), normal weight (≥15th - < 85th percentile), over weight (≥ 85th percentile to < 95th percentile) and obese (≥ 95th percentile). Reference BMI percentiles were derived from the first National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).30 This classification is in accordance with the recommendation of the expert committee on clinical guidelines for overweight in adolescence31 and World Health Organization (WHO) expert committee in overweight.32 Thin and underweight categories were combined in the analysis.

Weight management goals were assessed by asking students to report on what they were doing about their weight. Responses included: lose weight, gain weight, stay the same weight, not trying to do anything about weight. Their Weight management practices were assessed using the four separate questions mentioned above. The first three questions were: During the last 30 days, did you do any [exercise, eat less food, fewer calories or low fat food, stay without eating for 24 hours or more] to lose weight or try not to gain weight? (Responses included: no, yes). The fourth question was, excluding sports at schools, how often do you exercise vigorously enough to work up sweat? Responses included: never or rarely, 1-3 times per month, once per week, 2-4 times per week, 5-6 times per week, and daily.

Data entry and analysis

Data entry and analysis were done using SPSS for windows version 9.0. Proportions, prevalence, and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) were calculated. Multiple logistic regression models were fitted to calculate the adjusted Odds Ratio (OR) for being grossly overweight (obese) by self-perception, separatelyl for male and female students to determine the predictors of perceived obesity. In subsequent analyses, separate logistic regression models were used to determine the demographics and food choice behavior associated with specific weight management goals and practices. Differences between proportions and prevalence estimates were considered statistically significant if (95% CI) did not overlap, and adjusted odds ratios were considered statistically significant if (95% CI) did not include 1.0.

RESULTS

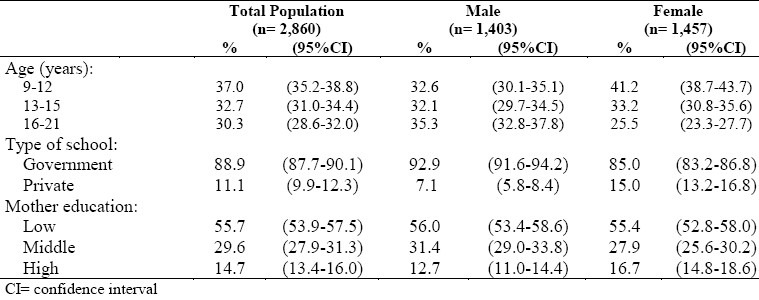

A total of 2,860 students of Saudi nationality were included in the study (Table 1). There were 49.1% males and 50.9% females. Their ages ranged from 9-21 years (mean=13.9, SD=2.8). The majority (88.9%) attended government schools and 14.7% of students’ mothers reached high level of education. Compared to females, males were older in age, more in government schools and their mothers were at the lower educational level.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of Saudi school students in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia 2000

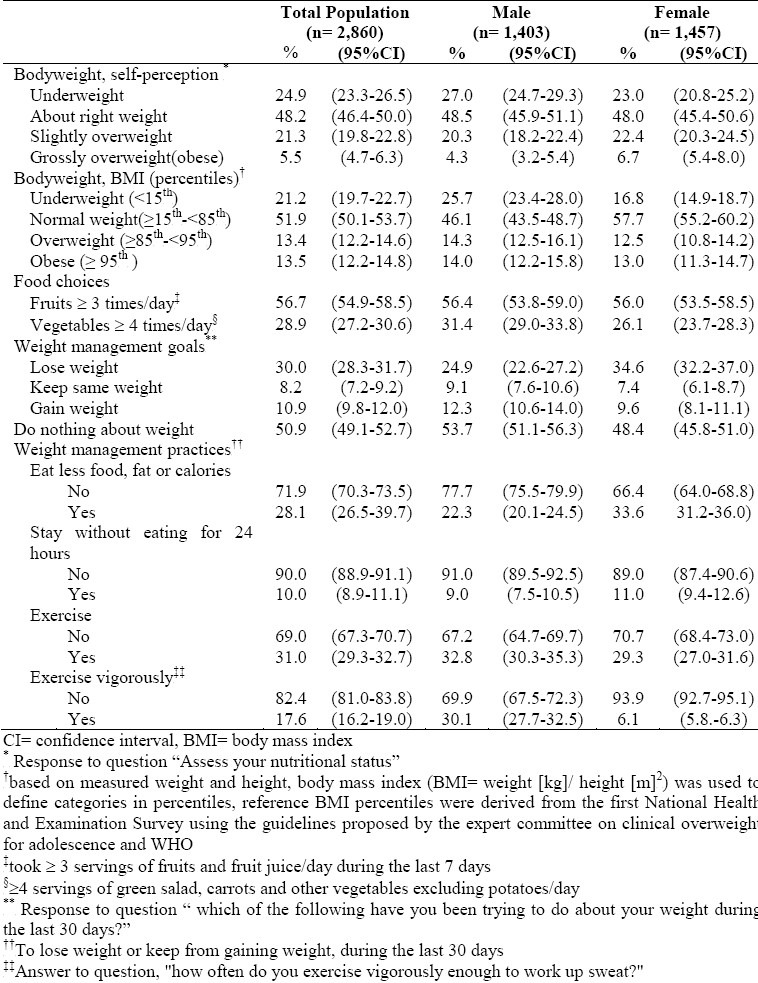

As shown in Table 2, the overall students’ perception of their body weight was nearly similar to their measured body mass index classification except in the group of overweight students, where 21.3% of the students perceived themselves as slightly overweight and only 5.5% as grossly overweight (obese), although 13.4% of students were actually classified by measured BMI as overweight and 13.5% as obese. Similar misclassifications of the overweight and obese were detected for both genders. Also, 56.7% took ≤ 3 fruit or fruit juice servings per day and similar proportions were detected for males and females. Only a third ate ≤ 4 vegetable servings per day, with males eating more vegetables than females. Around half of the students had no plans to do anything about their weight. The weight management goals differed by gender as males either tended to keep their weight or gain weight while females were keener to lose weight. Approximately, a third of the students reported that they ate less food, fat or fewer calories and 10.0% stayed without eating for at least 24 hours. Females were more likely to decrease their food, fat and calorie intake and stay for at least a day without eating than males. Among all students 31.0% did physical exercise and only 17.6% participated in vigorous physical activity. Female students were less likely than males to participate in physical exercise, especially vigorous exercise.

Table 2.

Perceived body weight, measured body weight (BMI), food choice and weight management goals and practices among Saudi school students by gender in Jeddah Saudi Arabia, 2000

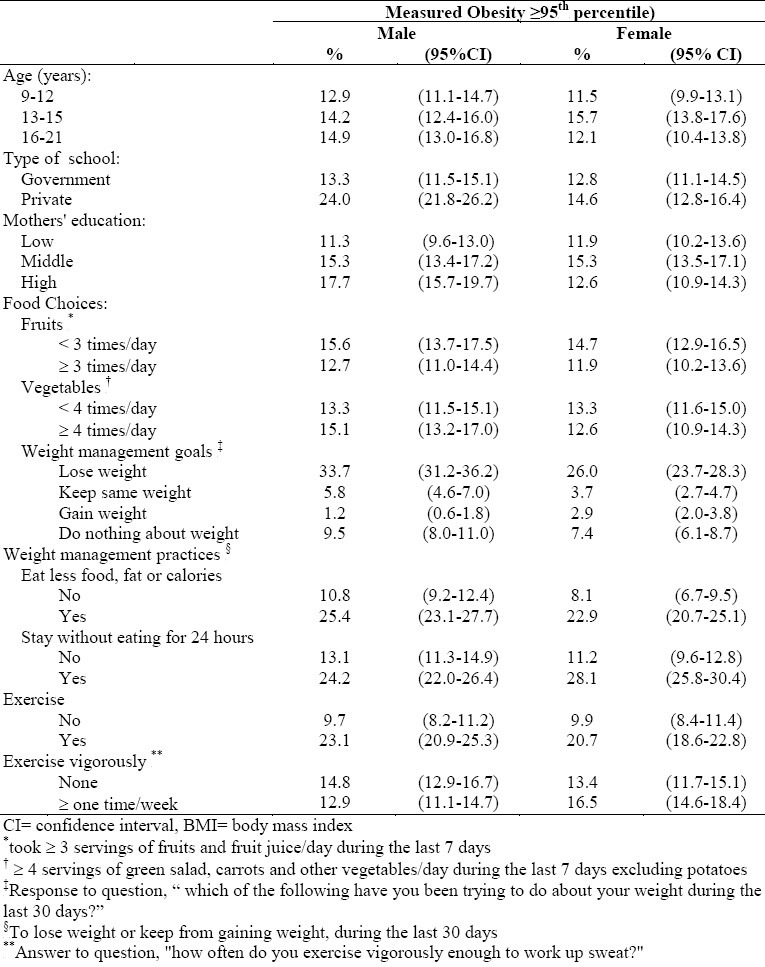

The bivariate analysis in (Table 3) contains the percent (prevalence) of measured obesity in each of the categories of a specific variable. It showed that the actually obese male students were those attending private schools, born to mothers of middle and high educational level, had the weight management goal to lose weight, had practiced weight management in the form of staying without eating for at least 24 hours, ate less food, fat or calories and exercised. Actually obese females were those in the 13-15 years old age group, who had weight management goals to lose weight, had practiced weight management in the form of staying without eating for at least 24 hours, ate less food fat or calories and had exercise.

Table 3.

Prevalence of measured obesity with demographic factors, food choice, weight management goals and practices among school students by gender in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia 2000

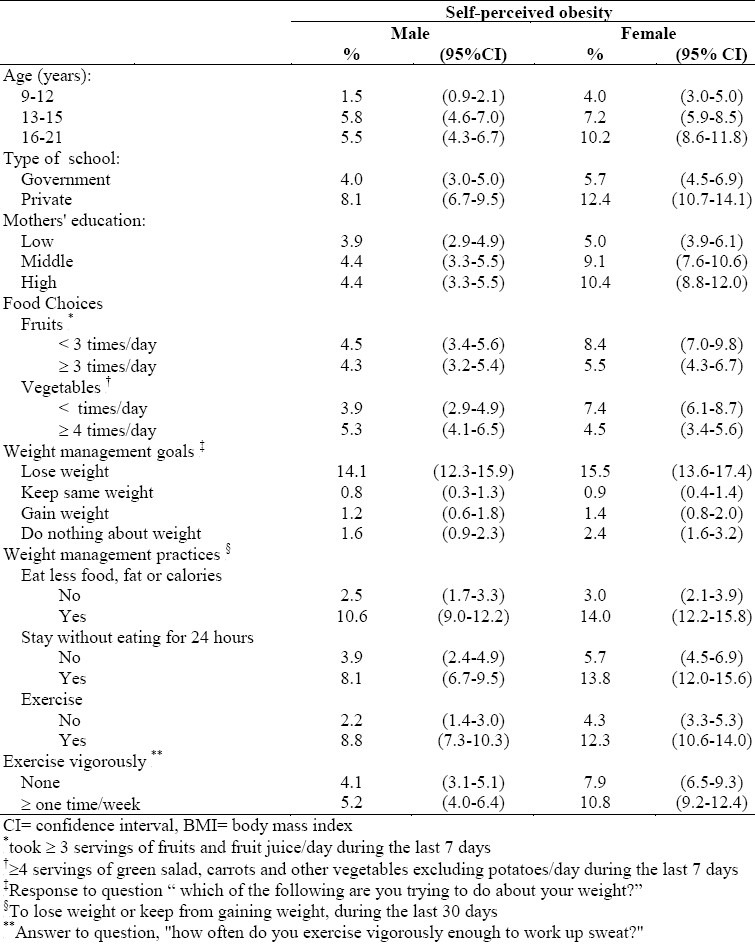

Self-perception of being grossly overweight (obese) is shown in Table 4. Older males aged 13-15 and 16-21 years compared to 9-12 years, and attending private schools, were those who perceived themselves as obese. Older females attending private schools, born to middle and highly educated mothers and taking less than three fruits or fruit juice servings and less than four vegetable servings daily were those who perceived themselves as obese. Both males and females who perceived themselves as obese intended to lose weight, ate less food, fat or calories, stayed for at least 24 hours without eating and had exercise.

Table 4.

Prevalence of perceived grossly overweight (obese) with demographic, food choice, weight management goals and practices among school students by gender in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia 2000

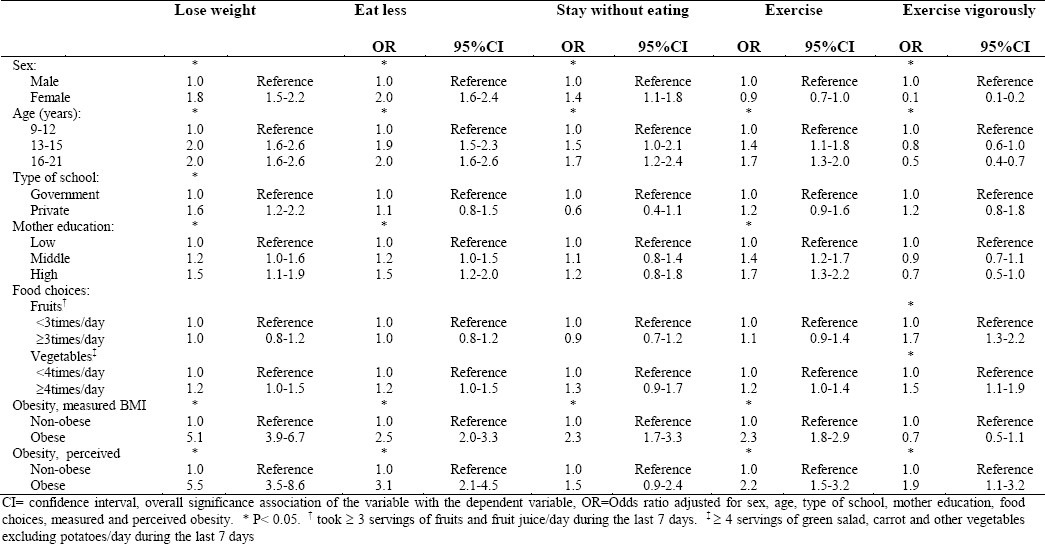

Multiple logistic regression models were fitted to examine the effect of various risk factors on trying to lose weight and weight management practices. As shown in Table 5, factors associated with trying to lose weight were being female, older in age, attending private school, born to highly educated mother, actually obese and perceiving oneself as obese. While for weight management practices, those who ate less food, fat or calories were the females, older, born to highly educated mothers, the actually obese and those who perceived themselves as obese. Still those who stayed for at least 24 hours without eating were the females, belonged to the older age groups, the actually obese and those who perceived themselves as obese. Physical activity in the form of exercise was associated with the older groups, those born to middle and highly educated mothers, the actually obese and those who perceived themselves as obese. Lastly, participation in vigorous exercise was mainly among males, the younger age groups, those who ate at least 3 fruit servings and at least 4 vegetable servings per day and those who perceived themselves as obese.

Table 5.

Adjusted odds ratio (OR) for trying to loose weight and weight management practices among school students by demographic characteristics, food choices, measured and perceived grossly overweight (obese) in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia 2000

DISCUSSION

The distribution of self perception of body size was similar to the classification of the measured body mass index except for those who perceived themselves as overweight. Although 13.4% of students were classified by measured body mass index into overweight and 13.5% as obese, 21.3% of students perceived themselves as slightly overweight and 5.5% as grossly overweight. This misclassification was reported by both genders. The meaning of “obesity” differs from the medical definition for many people, particularly pre-adolescence and adolescence age. Clinical and public health weight reduction programs, which do not take this into account, are unlikely to be successful, for the simple reason that those students who were actually obese may perceive themselves as slightly overweight or normal weight, and so do nothing to lose weight. Females were less likely than males to be overweight and obese but more likely to perceive themselves as grossly overweight (obese) and more likely to attempt to lose weight. Increasing age was the only risk factor that influences males to perceive themselves as obese. Among females, the risk factors associated with perceiving themselves as obese were increasing age, being in private schools and high maternal level of education. Age and gender differences in the perception of body weight have been previously described.33,34

Fruit and vegetable intake are very important measures to ensure healthy low calorie diet.25,26 Over half of the students reported that they took at least 3 fruits or fruit juice servings daily and third of them ate at least 4 vegetable servings daily. This large percentage of daily intake of fruits could be due to the high consumption of canned fruit juices rather than fresh fruits or fresh juices in this age group. French fries could be responsible for the high daily reported intake of vegetables. Students could have assumed that french fries could stand for ordinary potatoes which were specifically mentioned in the vegetables intake question, as a vegetable serving. This false level in the number of fruit and vegetable servings taken per day could explain the non-association found between the attempt to lose weight and weight management practices, (especially those concerning food intake) and daily intake of either vegetables or fruits. Similar findings were detected in previous studies.34 Before considering the implications of this finding, a methodological limitation in measuring dietary behaviors must be acknowledged. A multiple 24-hour dietary recalls or semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaires with extensive dietary food items would give a better estimation of fruits and vegetable intake. The goal of a third of students was to lose weight. This number agrees with the proportion of the actually overweight and obese. The figure was less than the figure of American undergraduate college students attempting to lose weight. Nearly half (46%) of the total number investigated were trying to lose weight although they were not as overweight and obese as the Saudi students.34 Around, 28.0% ate less food, fat or calories. Only 31.0% did exercise and 17.6% were engaged in vigorous exercise to lose weight or avoid gaining weight, which is low compared to American students, 50% of whom did normal exercise and 64% of whom were engaged in vigorous exercise.35 In our study, the lack of exercise was found to be even worse in females than in males. In a study done on Saudi women from an urban health center in the Eastern province in Saudi Arabia similar findings were obtained. In that study 75% of these women were either not exercising at all or doing so in frequently, a feature expected in the middle and lower social class group of women in this region.29 Females were more likely than males to try to lose weight. Besides, females were more likely than males to reduce their food, fat or calories intake but less likely to participate in vigorous exercise in an effort to lose weight or keep from gaining weight. These results confirm previous research findings showing that weight loss attempts were prevalent; that especially older age groups actively made the effort to lose weight or avoid gaining weight; that males were the ones who usually excercised;36–38 and that diet restriction was usually by females.37 Older students, especially females, were more likely to adopt regular, rather than vigorous exercise to lose weight since compared to the male schools, female schools were less likely to include exercise or physical activity in general in its program. Cultural barriers and societal restriction added more to the discrepancy since females in general in Saudi society do not exercise in public. Even the small number of female health clubs allowed to function in the Kingdom have a membership of women of high social class only. Potentially harmful weight control by abstaining from food for at least 24 hours was the practice of 10.0% of the students. Females were again more likely to employ potentially harmful measures to reduce their weight than males.

High social class, reflected by attendance at private schools and high maternal education, was another factor associated with perception of onself as obese especially among females. High social class was still associated with the desire to lose weight, eat less food, fat or calories and have exercise. These results emphasize the importance of education in general and maternal education in particular to combat overweight and obesity and the adoption of healthy weight management practices.

Overweight and obesity start as early as childhood and influence adult body size. Thus actions to combat these two conditions should start early in childhood. Schools provide an ideal forum for reaching large numbers of youngsters. More than 3.9 million students are currently enrolled in the Kingdom's 20,000 schools. The educational setting in schools provide numerous opportunities to positively influence physical activity and nutrition, increase students’ awareness of ideal body size and clinical obesity, strengthen weight management goals, and advocate healthy weight management practices, especially in adolescent females to prevent and treat overweight and obesity. There is a dearth of nutritional health education intervention programs in schools. These should be developed and implemented to encourage and ensure engagement in moderate physical activity (such as walking), especially among females and older adolescents. This can be an effective method of increasing caloric expenditure, promote fresh fruit and vegetable intake an important component of a nutritionally rich, low caloric diet; rather than canned fruit juices and french fries; discourage harmful weight control measures, and increase students’ awareness of ideal body size and clinical obesity.

In conclusion, many of our adolescents in schools are putting their health at risk through lifestyle choices that include insufficient physical activity and unhealthy food choices, resulting in a high prevalence of overweight and obesity. Not all obese adolescents have a correct image of their body size. Information from our cross-sectional survey provides the data base that can help in developing intervention programs which are recommended for use from childhood through school age to promote healthy food choices, encourage physical exercise and discourage potentially harmful weight control measures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Manson JL, Stampfer MI, Hennekens CH, Willett WC. Body weight and longevity: a reassessment. JAMA. 1987;257:353–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rimm EB, Stampfer M, Giovannucci E, Ascherio A, Spiegel-Man D, Colditz GA, Willet WC. Body size and fat distribution as predictors of coronary heart disease among middle-aged and older US men. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;141:1117–27. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Larsson B. Obesity, fat distribution and cardiovascular disease. Int J Obesity. 1991;15:53–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Despres JP, Moorjani S, Lupien PJ, Tremblay A, Nadeau A, Bouchard C. Regional distribution of body fat, plasma lipo- proteins, and cardiovascular disease. Arteriosclerosis. 1990;10:497–511. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.10.4.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stamler R, Stamler J, Ricdlinger WF, Algera G, Roberts RH. Weight and blood pressure: findings in hypertension screening of one million Americans. JAMA. 1978;240:1607–10. doi: 10.1001/jama.240.15.1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kannel WB, Brand N, Skinner JJJ, Dawber TR, McNamara PM. The relations of adiposity to blood pressure and development of hypertension. Ann Intern Med. 1967;67:48–59. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-67-1-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan JM, Rimm EB, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC. Obesity, fat distribution, and weight gain as risk factors for clinical diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1994;17:961–9. doi: 10.2337/diacare.17.9.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zimmet P, Dowse G, Finch C, Sergeantson S, King H. The epidemiology and natural history of NIDDM - lessons from the South Pacific. Diabetes Metab Rev. 1990;6:91–124. doi: 10.1002/dmr.5610060203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hartz AJ, Rupley DC, Jr, Kalkhoff RD, Rimm AA. Relationship of obesity to diabetes: influence of obesity and body fat distribution. Prev Med. 1983;12:351–7. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(83)90244-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pi-sunyer FX. Medical hazards of obesity. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:655–60. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-7_part_2-199310011-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guo SS, Roche AF, Chumlea WC, Gardner JD, Siervogel RM. The predictive value of childhood body mass index values for overweight at age 35 y. Am J Clin Nutr. 1994;59:810–9. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/59.4.810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hill AJ, Oliver S, Rogers PJ. Eating in the adult world: the rise of dieting in childhood and adolescence. Brit J Clin Psychol. 1992;31:95–105. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1992.tb00973.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wadden TA, Foster GD, Stunkard AJ, Linowitz JR. Dissatisfaction with weight and figure in obese girls: discontent but not depression. Int J Obes. 1989;13:89–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hill AJ, Draper E, Stack J. A weight on children's minds: body shape dissatisfaction at 9 years old. Int J Obes. 1994;18(6):383–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gortmaker SL, Must A, Perrin JM, Sobol AM, Dietz WH. Social and economic consequences of overweight in adolescence and young adulthood. New Engl J Med. 1993;329:1008–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309303291406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crawley HF, Shergill-Bonner R. The nutrient and food intakes of 16-17 year old female dieters in the UK. J Hum Nutr and Dietetics. 1995;8:25–34. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patton GC, Johnson-Sabine E, Wood K, Mann AH, Wakeling A. Abnormal eating attitudes in London schoolgirls-a prospective epidemiological study: outcome at twelve month follow-up. Psychol Med. 1990;20:382–94. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700017700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rogers PJ, Edwards S, Green MW, Jas P. Nutritional influences on mood and cognitive perfornance: the nenstrual cycle, caffeine and dieting. Proc Nutr Soc. 1992;51:343–51. doi: 10.1079/pns19920048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Atlanta. GA: US Dept of Health and Human Services; 1996. US Dept of Health and Human Services. Physical activity and health: a report of the Surgeon General. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pate RR, Pratt M, Blair SN, et al. Physical activity and public health: a recommendation from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Sports Medicine. JAMA. 1995;273:402–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.273.5.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Obesity, preventing and managing the global epidemic: Report of the WHO consultation on obesity. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1997. World Health Organization. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garrow JS, Summerbell CD. Meta-analysis: Effect of exercise, with or without dieting, on the body compostion of overweight subjects. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1995;49:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pavlou KN, Krey S, Steffee WP. Exercise as an adjunct to weight loss and maintenance in moderately obese subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 1989;49:1115–23. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/49.5.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saris WHM. Fit, fat and fat free: The metabolic aspects of weight control. Int J Obes. 1998;22:S15–S21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Obesity, preventing and managing the global epidemic: Report of the WHO consultation on obesity. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1997. World Health Organization. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’ Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults. Washington, DC: US Dept of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service. National heart, lung and blood institute; 1998. National Institutes of Health. [Google Scholar]

- 27.American Medical Association. Council on Scientific Affairs. Treatment of obesity in adults. JAMA. 1988;260(25):17–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nichter M, Nichter M. Hype and weight. Medical Anthropolol. 1991;13:249–84. doi: 10.1080/01459740.1991.9966051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rasheed P. Perception of body weight and self-reported eating and exercise behaviour among obese and non-obese women in Saudi Arabia. Public Health. 1998;112(6):409–14. doi: 10.1038/sj.ph.1900479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Must A, Dallal GE, Dietz WH. Reference data for obesity: 85th percentiles of body mass index (wt/ht2) and triceps skin fold thickness. Am J clin Nutr. 1991;53:839–46. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/53.4.839. Erratum: Am J clin Nutr 1991;54:773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Himes JH, Dietz WH. Guidelines of overweight and adolescent preventive services: Recommendation from an expert committee. Am J clin Nutr. 1994;59:307–16. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/59.2.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.WHO Physical Status; The use and interpretation of Anthropometry. WHO Technical Report 854. 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garner DM, Garfinkel PE, Schwartz D, Thompson M. Cultural expectations of thinness in women. Psychol Rep. 1980;47:483–91. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1980.47.2.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lowry R, Galuska DA, Fulton JE, Wechsler H, Kann L, Collins JL. Physical activity, Food Choice, and Weight Management Goals and Practices Among U.S. College Students. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18(1):18–27. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(99)00107-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kann L, Warren CW, Harris WA. Youth risk behavior surveillance - United States, 1995. In: CDC surveillance summaries, September 1996. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1996;45:1–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Timperio A, Cameron-Smith D, Buras C, Salmon J, Crawfird D. Physical activity beliefs and behaviours among adults attempting weight control. Int J obesity. 2000;24:81–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Crawford D, Owen N, Broom D, Worcester M, Oliver G. Weight-control practices of adults in a rural community. Aust NZ J Public Health. 1998;22:73–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.1998.tb01148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Levy AS, Heaton AW. Weight control practices of US adults trying to lose weight. Ann Intern Med. 1993;199:661–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-7_part_2-199310011-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]