Abstract

Through bioassay-guided fractionation of the extracts from the aerial parts of the Chinese herb Hypericum japonicum Thunb. Murray, Isojacareubin (ISJ) was characterized as a potent antibacterial compound against the clinical methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). The broth microdilution assay was used to determine the minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) and minimal bactericidal concentrations (MBCs) of ISJ alone. The results showed that its MICs/MBCs ranged from 4/16 to 16/64 μg/mL, with the concentrations required to inhibit or kill 50% of the strains (MIC50/MBC50) at 8/16 μg/mL. Synergistic evaluations of this compound with four conventional antibacterial agents representing different types were performed by the chequerboard and time-kill tests. The chequerboard method showed significant synergy effects when ISJ was combined with Ceftazidime (CAZ), Levofloxacin (LEV) and Ampicillin (AMP), with the values of 50% of the fractional inhibitory concentration indices (FICI50) at 0.25, 0.37 and 0.37, respectively. Combined bactericidal activities were also observed in the time-kill dynamic assay. The results showed the ability of ISJ to reduce MRSA viable counts by log10CFU/mL at 24 h of incubation at a concentration of 1 × MIC were 1.5 (LEV, additivity), 0.92 (CAZ, indifference) and 0.82 (AMP, indifference), respectively. These in vitro anti-MRSA activities of ISJ alone and its synergy with conventional antibacterial agents demonstrated that ISJ enhanced their efficacy, which is of potential use for single and combinatory therapy of patients infected with MRSA.

Keywords: anti-MRSA activity, Hypericum japonicum, Isojacareubin, MIC, synergy

1. Introduction

Presently, the global spread of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is of great concern in the treatment of Staphylococcal infections, since it has quickly acquired resistance to all clinical antibacterial agents. Even a glycopeptides resistant strain, i.e., Vancomycin resistant S. aureus (VRSA) has also been reported [1]. MRSA has become the most common cause of infections among many pathogenic bacteria, leading to many life-threatening diseases such as endocarditis, pneumonia and toxin shock syndrome. In our hospital, MRSA could be found in over 80 percent of sputum samples of pneumonia elderly patients in the intensive care unit (ICU). Therefore, the developing of agents with novel modes of action is vital for overcoming this troublesome pathogen. Synergy of photochemicals with antibiotics has been viewed as approaching a new generation of phytopharmaceuticals [2,3]. We are devoting effort to search for novel anti-MRSA agents from plant sources with use in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) in recent years [4–8].

Hypericum japonicum Thunb. ex Murray (Di-er-cao or Tian-ji-huang in Chinese; Guttiferae) was first recorded in Zhiwu Mingshi Tukao (or Illustrated Catalogue of Plants) which dates back to 1848 [9,10]. This medicinal plant has been used to treat viral hepatitis and other infectious diseases for over one hundred years. Bioassay-guided fractionation of the alcoholic extract of the aerial parts of Hypericum japonicum led us to identify an anti-MRSA xanthone Isojacareubin (ISJ). The present report investigates the anti-MRSA activity of this compound alone and its synergistic effects in combination with conventional antibacterial agents.

2. Results and Discussion

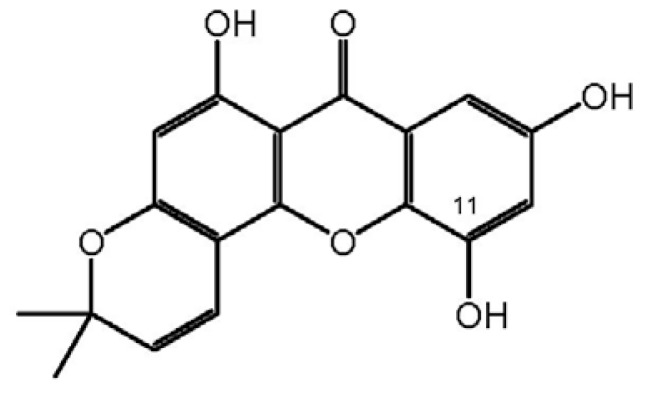

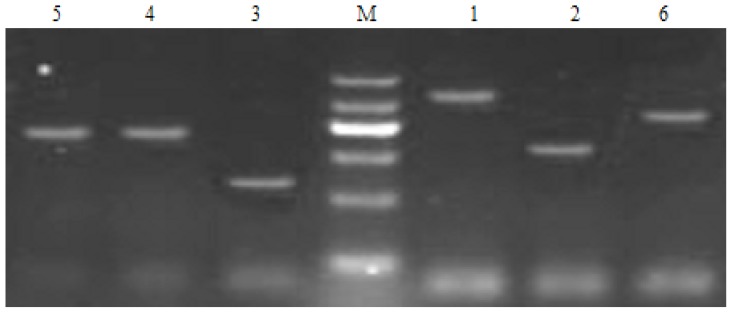

ISJ was isolated through bioassay-guided fractionation of extracts from H. japonicum (Table 1) [4]. Its structure was elucidated and identified mainly by spectral analysis and compared with a previous report (Scheme 1) [11]. Ten MRSA isolates, which were used for the evaluation of antibacterial activities, were characterized [4–8], and the presence of the mecA gene and SCCmec genotypes (Figure 1) was demonstrated through multiplex PCR experiments [12].

Table 1.

The screening results of different extraction parts (diameter of inhibition zone: mm)a.

| Strainsa | MSSA (ATCC25923) | MRSA 004 |

|---|---|---|

| Petroleum ether part | 29 | 23 |

| Ethyl acetate part | 22 | 23 |

| Sub-ethyl acetate fraction-A (Fr. A) | 17 | 23 |

| Sub-ethyl acetate fraction-B (Fr. B) | 20 | 15 |

| Sub-ethyl acetate fraction-C (Fr. C2) | 30 | 29 |

| n-Butanol part | 15 | 17 |

| Water part | 15 | 12 |

| Vancomycin | 30 | 30 |

Determined at a concentration of 30.0 mg/mL for the extracts and 1.0 mg/mL for Vancomycin;

MSSA: methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus; MRSA 004: A strain of methicillinresistant S. aureus.

Scheme 1.

The structure of Isojacareubin (ISJ).

Figure 1.

SCCmec III genotyping of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) genes (M: marker, 1: mecA, 2: CCRA1, 3: CCRA2, 4: CCRA3, 5: mec I, 6:IS1272).

The in vitro anti-MRSA activities of ISJ and four conventional antibacterial agents, i.e., Ampicillin (AMP), Ceftazidime (CAZ), Levofloxacin (LEV) and Azithromycin (AZM) both alone and combined, against the 10 clinical MRSA strains of SCCmec III type [12] are shown in Table 2. The ranges of minimal inhibitory concentrations/minimal bactericidal concentrations (MICs/MBCs, μg/mL) alone were 4~16/16~64 for ISJ, within the order of potency as ISJ (4~16/16~64) = LEV (4~16/8~64) > AMP (16~128/64~512) > CAZ (128~512/128~ >1024) >> AZM (>1024), so the potency of ISJ and LEV were nearly equivalent. In the control experiments, MICs and MBCs of Vancomycin and ISJ against the methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA, ATCC 25923) strain were 1/2 and 8/16 μg/mL, respectively.

Table 2.

MICs (/MBCs; μg/mL) and fractional inhibitory concentration indices (FICIs) of Isojacareubin in combination with four conventional antibacterial agents against 10 clinical isolates of SCCmec III type MRSA.

| Agents | ISJa | AMP | CAZ | LEV | AZM | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Alone | Alone | Combb | Alone | Comb | Alone | Comb | Alone | Comb | |

| Ranges of MIC (/MBC) (μg/mL)c | 4(/16)~ 16(/64) | 16(/64)~ 128(/512) | 4~16 + 1~4 | 128(/128)~ 512(/ex) + 32~128 | 32~128 + 1~4 | 4(/8)~ 16(/64) | 1~4 + 1~4 | ex | 512~1024 + 4~16 |

| MIC50c | 8 | 64 | 8 + 4 | 512 | 32 + 1 | 16 | 2 + 2 | - | 1024 + 8 |

| MIC90 | 16 | 128 | 16 + 4 | 512 | 64 + 4 | 16 | 4 + 4 | - | 1024 + 16 |

| Ranges of FICId | - | - | 0.37~0.62 | - | 0.25~0.5 | - | 0.25~0.5 | - | 1~1.5 |

| FICI50 | - | - | 0.37 | - | 0.25 | - | 0.37 | - | 1.5 |

| FICI90 | - | - | 0.62 | - | 0.37 | - | 0.37 | - | 1.5 |

| Effect (%)e | - | - | ad(30) sn(70) | - | sn(100) | - | sn(100) | - | id(100) |

ISJ, Isojacareubin; AMP, Ampicillin; CAZ, Ceftazidime; LEV, Levofloxacin; AZM, Azithromycin;

Comb, combined (the binate data are expressed as values of single antibacterial + ISJ);

MIC50, concentration of inhibition against 50% of MRSA strains; MIC90, concentration of inhibition against 90% of MRSA strains; ex, concentration of >1024 μg/mL;

FICI50, FICI of inhibition against 50% MRSA strains; FICI90, FICI of inhibition against 90% MRSA strains;

ad, additivity; id, indifference; sn, synergy.

Tested by the chequerboard method [13], ISJ showed synergy when it was combined with various antibacterials, with the values of 50% of the fractional inhibitory concentration indices (FICI50) at 0.37 (AMP), 0.25 (CAZ) and 0.37 (LEV), respectively. However, the ISJ and AZM combination showed indifference (FICI50 = 1.50). The combination of ISJ with CAZ was observed as the most effective, with their values of MIC50 (μg/mL) reduced from 8 (ISJ alone) and 512 (CAZ alone) to 1 + 32 (ISJ + CAZ). Combination of ISJ and LEV was observed as less effective, with their values of MIC50 (μg/mL) reduced from 8 (ISJ alone) and 16 (LEV alone) to both 2 (ISJ + LEV). According to the CLSI interpretive standard for Staphylococcus spp., these values were close to the MICs (μg/mL) of breakpoints of LEV (≤1 for susceptible and ≥4 for resistant) and CAZ (≤8 for susceptible and ≥32 for resistant), respectively, which demonstrated significant potentiation of anti-MRSA effects (or even reversion of the resistance of the corresponding antibacterial agents against MRSA) [14].

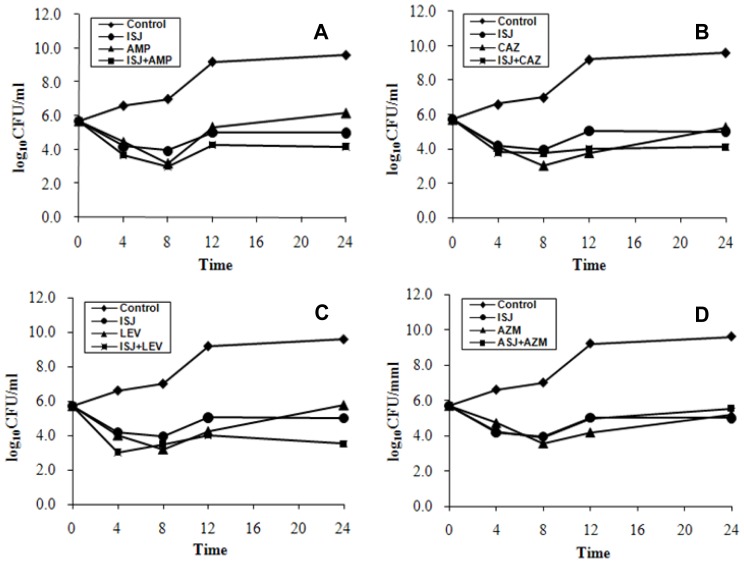

Time-kill curves (Figure 2) showed ISJ alone was the most effective at reducing the viable counts by 4.66 log10CFU/mL (−4.66, synergy) of MRSA at 24 h of incubation at the concentration of 1 × MIC, while the counts (log10CFU/mL) of combinations of ISJ with AMP (−0.82, indifference), CAZ (−0.92, indifference), LEV (−1.5, additivity) and AZM (+0.53, indifference) were also observed against MR004 (one of the ten isolates) (data not shown). Therefore, the combined bactericidal activities were not as potent as those of bacteriostatic at the concentration of 1 × MIC [15]. Concentrations of higher MIC times of ISJ might produce better combinatory bactericidal effects.

Figure 2.

Time-kill curves of the synergistic effect of the combination of Isojacareubin (ISJ) at 1 × MIC concentration with Ampicillin (AMP) (A); Ceftazidime (CAZ) (B); Levofloxacin (LEV) (C); and Azithromycin (AZM) (D); against MR004, a clinical MRSA strain of SCCmec III type.

H. japonicum is a Chinese herb used in TCM. Its 85% ethanol treated water extract was documented in Chinese Pharmacopoeia as an injection for the treatment of viral hepatitis [16]. In Europe, a plant of the same genus, i.e., H. perforatum is known by the name St John’s wort, which is a first-line herbal medicine used for mild to moderate depression [17]. These records demonstrated their safety of therapeutic properties. ISJ is a characteristic constituent in H. japonicum and was first found in the plant by Ishiguro et al. [11]. Although many xanthone derivatives have been studied for their antimicrobial (including anti-MRSA) activities, the limited distribution in plant resources has meant that ISJ remained as yet to be investigated to the best of our knowledge [18–20]. For the first time we studied its anti-MRSA activities in this report.

As the clinical MRSA which was originally called the “superbug” has been haunting us in recent years and has become an increasingly pressing clinical problem worldwide, anti-MRSA synergistic effects between plant natural compounds and conventional antibacterial agents has further been demonstrated here as a promising way of overcoming current antibiotic resistances [3].

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Plant Materials

The aerial parts of H. japonicum were purchased from the crude drug mart in Kunming, China. They were identified at the Botany Department, Kunming Institute of Botany (KIB), the Chinese Academy of Sciences. The voucher specimen is deposited at the herbarium of KIB.

3.2. Bacterial Strains and Media

MRSA strains (ten isolates with SCCmec III genotype) were obtained and characterized from the infectious sputum samples of critically ill patients in Kunming General Hospital [14,21,22]. The presence of mecA gene and SCCmec genotypes were determined by multiplex PCR method (Figure 1) [12]. ATCC 25923 was used as the control strain. Standard Mueller-Hinton agar and broth (MHA and MHB, Tianhe Microbial Agents Co., Hangzhou, China) were used as bacterial culture media. MHB was used for all susceptibility testing and time–kill experiments. Colony counts were determined using MHA plates.

3.3. Antibacterial Agents

Four antibacterial agents representing four conventional agents used in clinic were purchased from the manufacturers, i.e., Ampicillin (AMP) (North China pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Shijiazhuang, China), Ceftazidime (CAZ) (Jida pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Kunming, China), Azithromycin (AZM) and Levofloxacin (LEV) (Yangzhijiang pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Taizhou, China). Vancomycin (Eli Lilly Japan K. K., Seishin Laboratories) was used as the positive control agent. Standard Cefoxitin disks were purchased from Tiantan biological products Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China).

3.4. Bioassay-Guided Isolation and Identification of ISJ

Powdered aerial parts of H. japonicum (4.7 kg) were extracted with 80% ethanol and the extract (500 g) was successively fractionated between water and petroleum ether (P), ethyl acetate (E) and n-butanol to afford four fractions. The E fraction (90 g), which showed the most activity by the agar diffusion test described in Section 3.5 below (Table 1) [4], was subjected to column chromatography over silica gel (300–400 mesh; Qingdao, China) and eluted (200 mL/fraction) with ethyl acetate. TLC monitored the eluates and combined to afford three sub-fractions (Frs. A–C1-6), gradient elution of Fr. C2 with P-E-M (methanol) (4:1:0.2–1:1:0.5) to furnish 20 mg of pure ISJ: light-yellow powder; C18H14O6, ESI-MS: m/z 327 ([M + 1]+); 1H NMR (400 MHz) δ: 7.58 (1H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, H-8), 7.05 (1H, d, J = 10.0 Hz, H-4′), 6.92 (1H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, H-7), 6.15 (1H, s, H-2), 5.72 (1H, d, J = 10.0 Hz, H-3′), 1.44 (6H, s, 2′, 2Me); 13C NMR (100 MHz) δ: 162.8 (C-1), 98.8 (C-2), 160.2 (C-3), 102.7 (C-4), 51.7 (C-4a), 146.5 (C-4b), 132.9 (C-5), 152.9 (C-6), 115.4 (C-7), 116.6 (C-8), 113.3 (C-8a), 180.4 (C-9), 101.4 (C-9a), 78.6 (C-2′), 127.8 (C-3′), 113.8 (C-4′), 28.3 (C-2′-Me). All the spectral data were identical with the literature [11].

3.5. Susceptibility Testing

The inhibition zone diameters (IZDs, mm) of the extracts (30 mg/mL in dimethyl sulfoxide) were determined by the agar diffusion method on MHA plates with inoculums of 1.5 × 108 CFU/mL of the microorganisms following the previous report [5]. MICs/MBCs were determined by standardized broth microdilution techniques with the final inoculums of 5 × 105 CFU/mL in each well of the 96-well plate according to the CLSI guidelines and incubated at 35 °C for 24 h [23,24]. All the experiments were performed in duplicate, with concentrations ranging up to 1024 mg/L for AZM.

3.6. Synergy Testing

Potential anti-MRSA synergy was measured by FICIs from the chequerboard method and by time-kill curves as previous report [13]. The FIC of the combination was calculated by dividing the MIC of the ISJ-antibacterial agent combination by the MIC of ISJ or of the antibacterial agent used alone. The FICI was obtained by adding the FIC of the ISJ and that of the antibacterial agent. The FICI results were interpreted as follows: FICI ≤ 0.5, synergy; 0.5 < FICI ≤ 1, additivity; and 1 < FICI < 2, indifference (or no effect) and FICI ≥ 2, antagonism [13,25]. In the killing curves, synergy was defined as ≥2 log10 CFU/mL increase in killing at 24 h with the combination, in comparison with the killing by the most active single drug. Additivity was defined as a 1–2 log10 CFU/mL increase in kill with the combination in comparison with the most active single agent. Indifference was defined as ±1 log10 CFU/mL killing or growth. Combinations that resulted in >1 log10 CFU/mL bacterial growth in comparison with the least active single agent were considered to represent antagonism [15,26]. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

4. Conclusions

The in vitro anti-MRSA activities of Isojacareubin (ISJ) alone and its synergistic effects when used in combination with antibacterial agents demonstrated that ISJ may have potential clinical usage to enhance the efficacy of current antibacterials such as Ceftazidime and Levofloxacin, which warrants further pharmacological studies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC 81073126) and the supporting funds of Yunnan Provincial Science and Technology Department (2008PY001) and Medical Research Programme of Chengdu Military Region (MB09030) of China. We are also grateful to Kunming Institute of Botany (CAS) for spectral analysis.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Chang S., Sievert D.M., Hageman J.C., Boulton M.L., Tenover F.C., Downes F.P., Shah S., Rudrik J.T., Pupp G.R., Brown W.J., et al. Infection with vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus containing the vanA resistance gene. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:1342–1347. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa025025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wagner H., Ulrich-Merzenich G. Synergy research: Approaching a new generation of phytopharmaceuticals. Phytomedicine. 2009;16:97–110. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2008.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hemaiswarya S., Kruthiventi A.K., Doble M. Synergism between natural products and antibiotics against infectious diseases. Phytomedicine. 2008;15:639–652. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zuo G.Y., Wang G.C., Zhao Y.B., Xu G.L., Hao X.Y., Han J., Zhao Q. Screening of Chinese medicinal plants for inhibition against clinical isolates of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008;120:287–290. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zuo G.Y., Zhang X.J., Yang C.X., Han J., Wang G.C., Bian Z.Q. Evaluation of traditional Chinese medicinal plants for anti-MRSA activity with reference to the treatment record of infectious diseases. Molecules. 2012;17:2955–2967. doi: 10.3390/molecules17032955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zuo G.Y., Meng F.Y., Hao X.Y., Zhang Y.L., Wang G.C., Xu G.L. Antibacterial Alkaloids from Chelidonium majus Linn (Papaveraceae) against clinical isolates of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2008;11:90–94. doi: 10.18433/j3d30q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zuo G.Y., Li Y., Wang T., Han J., Wang G.C., Zhang Y.L., Pan W.D. Synergistic antibacterial and antibiotic effects of bisbenzylisoquinoline alkaloids on clinical isolates of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) Molecules. 2011;16:9819–9826. doi: 10.3390/molecules16129819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.An J., Zuo G.Y., Hao X.Y., Wang G.C., Li Z.S. Antibacterial and synergy of a flavanonol rhamnoside with antibiotics against clinical isolates of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) Phytomedicine. 2011;18:990–993. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tian-ji-huang. Selected Yunnan Traditional Chinese Herbs. I. Tianjin People’s Press; Tianjin, China: 1970. pp. 30–31. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Di-er-cao. Dictionary of Chinese Materia Medica. I. Shanghai Scientific Technical Press; Shanghai, China: 1977. pp. 813–814. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ishiguro K., Nagata S., Fukumoto H., Yamaki M., Isoi K., Oyama Y. An isopentenylated flavonol from Hypericum japonicum. Phytochemistry. 1993;32:1583–1585. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang K., McClure J.A., Elsayed S., Louie T., Conly J.M. Novel multiplex PCR assay for characterization and concomitant subtyping of staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec types I to V in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005;43:5026–5033. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.10.5026-5033.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu Z.Q., Zhao W.H., Asano N., Yoda Y., Hara Y., Shimamura T. Epigallocatechin gallate synergistically enhances the activity of carbapenems against methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents. Chemother. 2002;46:558–560. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.2.558-560.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing—17th Informational Supplement. CLSI; Wayne, PA, USA: 2007. Approved Standard M100-S17. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petersen P.J., Labthavikul P., Jones C.H., Bradford P.A. In vitro antibacterial activities of tigecycline in combination with other antimicrobial agents determined by chequerboard and time-kill kinetic analysis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2006;57:573–576. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Pharmacopoeia Committee of China. Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China (Part 1) Chemical Industry Press; Beijing, China: 1977. Tianjihuang zhusheye (Injectio Hyperici Japonici) pp. 199–200. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Di Carlo G., Borrelli F., Izzo A.A., Ernst E. St John’s wort: Prozac from the plant kingdom. Trends Pharmacol. Set. 2001;22:292–297. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01716-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chomnawang M.T., Surassmo S., Wongsariya K., Bunyapraphatsara N. Antibacterial activity of Thai medicinal plants against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Fitoterapia. 2009;80:102–104. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2008.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sukpondma Y., Rukachaisirikul V., Phongpaichit S. Antibacterial caged-tetraprenylated xanthones from the fruits of Garcinia hanburyi. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2005;53:850–852. doi: 10.1248/cpb.53.850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yasunaka K., Abe F., Nagayama A., Okabe H., Lozada-Perez L., Lopez-Villafranco E., Muniz E.E., Aguilar A., Reyes-Chilpa R. Antibacterial activity of crude extracts from Mexican medicinal plants and purified coumarins and xanthones. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005;97:293–299. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Disk Susceptibility Tests. CLSI; Wayne, PA, USA: 2006. Approved standard M02-A10. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kloos W.K., Bannerman T.L. Staphylococcus and Micrococcus. In: Murray P.R., Baron E.J., Pfaller M.A., Tenover F.C., Yolken R.H., editors. Manual of Clinical Microbiology. 7th ed. ASM Press; Washington DC, USA: 1999. pp. 264–282. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria that Grow Aerobically. 7th ed. CLSI; Wayne, PA, USA: 2006. Approved standard M7–A7. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) Methods for Determining Bactericidal Activity of Antimicrobial Agents. CLSI; Wayne, PA, USA: 1999. Document M26-A. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Orhan G., Bayram A., Zer Y., Balci I. Synergy tests by E test and chequerboard methods of antimicrobial combinations against Brucella melitensis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005;43:140–143. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.1.140-143.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chin J.N., Jones R.N., Sader H.S., Savage P.B., Rybak M.J. Potential synergy activity of the novel ceragenin, CAS-13, against clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, including multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2008;61:365–370. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]