SUMMARY

AU-rich elements (AREs), present in mRNA 3′-UTRs, are potent posttranscriptional regulatory signals that can rapidly effect changes in mRNA stability and translation, thereby dramatically altering gene expression with clinical and developmental consequences. In human cell lines, the TNFα ARE enhances translation relative to mRNA levels upon serum starvation, which induces cell-cycle arrest. An in vivo crosslinking-coupled affinity purification method was developed to isolate ARE-associated complexes from activated versus basal translation conditions. We surprisingly found two microRNP-related proteins, fragile-X-mental-retardation-related protein 1 (FXR1) and Argonaute 2 (AGO2), that associate with the ARE exclusively during translation activation. Through tethering and shRNA-knockdown experiments, we provide direct evidence for the translation activation function of both FXR1 and AGO2 and demonstrate their interdependence for upregulation. This novel cell-growth-dependent translation activation role for FXR1 and AGO2 allows new insights into ARE-mediated signaling and connects two important post-transcriptional regulatory systems in an unexpected way.

INTRODUCTION

Posttranscriptional modulation of gene expression in the cytoplasm involves RNA sequences that collaborate with trans-acting factors to regulate mRNA localization, translation, and stability (Valencia-Sanchez et al., 2006; Gray and Wickens, 1998). The AU-rich element (ARE) is a well-studied signal present in the 3′-UTR of many clinically relevant messages, including those of cytokines, oncogenes, and growth factors, whose deregulation can lead to immune disorders and cancer (Balkwill, 2002; Wilusz et al., 2001; Brewer, 2002). AREs are best known as decay elements (Wilusz et al., 2001; Bakheet et al., 2001), but they also regulate translation and mRNA export (Espel, 2005; Kontoyiannis et al., 1999).

The cytokine tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα), which is normally expressed in stimulated lymphocytes, is critical for inflammatory responses and malignancies (Balkwill, 2002). When circulating monocytes become adherent during the process of extravasation into inflamed tissues or in proangiogenic tumor infiltration, cell growth arrests with rapid changes in cytokine expression (Haskill et al., 1988), including that of TNFα, which further upregulates other cytokines necessary for maturation into macrophages (Jeoung et al., 1995; Moneo et al., 2003; Pomorski et al., 2004). This response can be recapitulated in cell culture by serum starvation (Haskill et al., 1988; Sirenko et al., 1997).

The 3′-UTR of TNFα mRNA is highly conserved among mammals with several important posttranscriptional regulatory elements, including a 34 nt ARE (Figure 1A). In mice, deletion of the TNFα ARE results in misregulated TNFα translation in macrophages, monocytes, and neutrophils (Kontoyiannis et al., 1999). In vitro, monocytic cell lines such as THP-1 respond to phorbol esters to regulate TNFα translation or to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) to regulate TNFα mRNA stability, both of which are mediated by the ARE (Andersson and Sundler, 2000; Brooks et al., 2004).

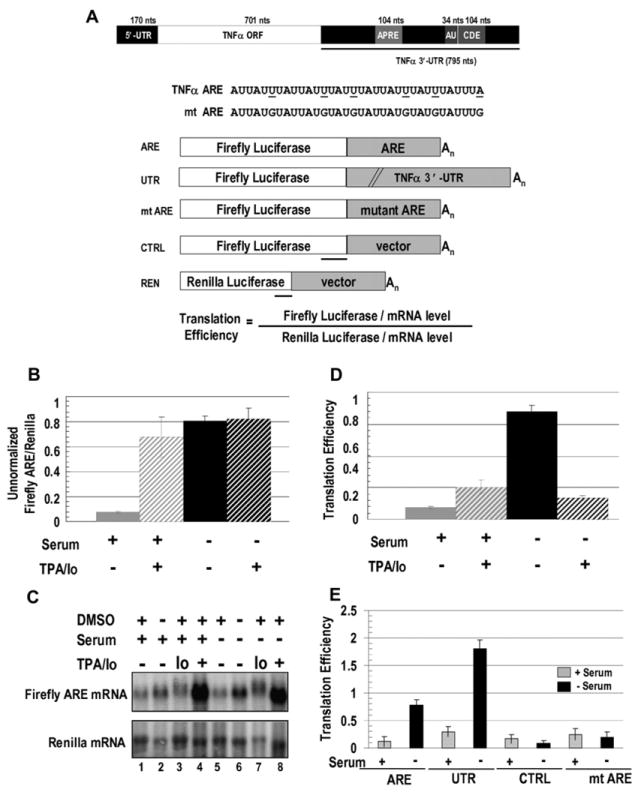

Figure 1. In Vivo Assay for ARE-Regulated Translation.

(A) TNFα mRNA with conserved regions, including a splicing regulator (APRE; Osman et al., 1999), the ARE (AU), and a constitutive decay element (CDE; Stoecklin et al., 2003) are shown. Firefly luciferase reporter constructs with the 34 nt TNFα ARE (ARE), the 795 nt TNFα 3′-UTR (UTR), the 34 nt mutant ARE (mt ARE), or a 34 nt vector sequence (CTRL) were cotransfected with a Renilla luciferase reporter (REN). Mutations in mt ARE and regions protected by the probes used in RNase protection assays (RPAs) are underlined.

(B) HEK293 cells were transfected with the ARE and REN reporters and 18 hr later were switched to serum-containing (+) or serum-lacking (−) medium containing either TPA/Io (see Experimental Procedures) or the DMSO solvent. Eighteen hours later, firefly and Renilla luciferase activities were assayed. The values in panels (B), (D), and (E) are averages from at least three transfections ± SD.

(C) Northern blots show ARE- and REN-reporter levels in ± serum, with TPA/Io, Io alone, and/or the solvent DMSO as indicated. Table S2 shows the RNA values.

(D) Luciferase values (B) were normalized to the mRNA levels (C) to obtain translation efficiencies (defined in Figure 1A; see Figure S1 and Tables S1 and S2). Since similar changes upon serum starvation without TPA/Io were observed without normalizing for RNA levels (B), normalization does not artificially produce an apparent increase in translation.

(E) Comparison of translation efficiencies of the ARE and UTR reporters relative to the control reporters, CTRL, and mt ARE in response to the presence or absence of serum without DMSO is shown.

ARE-binding proteins affect mRNA stability, but their contributions to translation control remain less well understood (Wilusz et al., 2001; Stoecklin et al., 2000; Brewer, 2002). Factors that bind the TNFα and other AREs in response to signaling pathways and that affect stability or translation include HuR (Brennan and Steitz, 2001; Mazan-Mamczarz et al., 2003), the Tristetraprolin (TTP) family of proteins (Carballo et al., 1998; Stoecklin et al., 2000), and FXR1. FXR1 exists as seven spliced isoforms that are highly conserved in mammals (Kirkpatrick et al., 1999, 2001) and that are associated with microRNAs and the RNAi machinery in both Drosophila (Caudy et al., 2002) and HeLa cells (Jin et al., 2004). FXR1 knockout and conditional knockout mice exhibit muscle wasting, decreased growth rate, and neonatal death with translational upregulation of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNFα (Mientjes et al., 2004; Garnon et al., 2005).

Several studies suggest the involvement of microRNPs as regulators of ARE-bearing mRNAs. First, RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), the functional microRNP, includes two ARE-associated proteins: PAI-RBP1 and FXR1 (Caudy et al., 2002); FXR1 interacts via Argonaute 2 (AGO2; Jin et al., 2004; Xu et al., 2004). AGO2 is the essential functional effector of the microRNP—the slicer in microRNA-mediated decay (Meister et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2004) or the repressor in microRNA-mediated translational repression (Pillai et al., 2004). Second, microRNAs have been localized to the same cytoplasmic bodies (Jakymiw et al., 2005; Liu et al., 2005a; Pillai et al., 2005) as ARE-binding proteins (Kedersha et al., 2005; Stoecklin et al., 2004). Third, miR16-1 regulates the level of a TNFα 3′-UTR-containing reporter RNA through TTP, which also interacts with RISC via AGO2 (Jing et al., 2005).

The goal of this study was to establish an in vivo system to study TNFα-ARE-mediated translation control and to determine the molecular nature of the ARE-associated regulators. We first show that the TNFα ARE upregulates translation in response to cell-cycle arrest in HEK293 cells and in THP-1 monocytes when induced by serum starvation or other treatments. This upregulation is physiologically relevant since cell-cycle arrest accompanies the differentiation of monocytes into macrophages in vivo. We then developed an affinity-purification scheme to isolate in vivo ARE-associated complexes from various translation conditions. Surprisingly, we find that FXR1 and AGO2, which previously were considered effectors of translation repression, associate with TNFα ARE and function as translation activators in response to serum starvation.

RESULTS

An In Vivo Assay for Translation Regulation by the TNFα ARE

We constructed firefly luciferase reporters containing either the minimal TNFα ARE (34 nt; ARE in Figure 1A) or the entire 3′-UTR (795 nt; UTR, Figure 1A) and transfected them into HEK293 and monocytic THP-1 cells. In all luciferase assays, the following controls were included: a co-transfected Renilla reporter bearing a vector sequence in its 3′-UTR (REN, Figure 1A) to normalize for extract concentrations, transfection efficiency, and overall translation status and a firefly luciferase construct with either a mutated ARE (mt ARE, Figure 1A) or vector sequence of the same size (CTRL, Figure 1A). To distinguish translational output from mRNA turnover, most luciferase assays were normalized to luciferase-reporter RNA levels to obtain the translation efficiency (defined in Figures 1A and S1).

The TNFα ARE Regulates Translation in Response to Serum

Translational upregulation of TNFα had previously been observed in response to phorbol esters (Andersson and Sundler, 2000; Garnon et al., 2005). The above reporters were therefore tested for luciferase expression after treatment with 12-O-tetradecanoyl-phorbol-13-acetate (TPA) and Ionomycin (Io) in serum-grown, as well as serum-starved cells (to avoid inhibitors potentially present in serum).

When HEK293 cells previously transfected with the ARE reporter were grown without TPA/Io in serum-containing media, a low basal level of translation (Figure 1B) as well as a low level of the reporter RNA (Figure 1C, lanes 1 and 2) were observed. However, after 18 hr in serum-starved conditions, firefly luciferase activity increased ~8-fold (Figure 1B) without a corresponding increase in RNA levels (Figure 1C, lanes 5 and 6; see Table S2 for quantitation of the RNA levels) or in the Renilla values used for normalization (Figure S1, compare graphs A and B; Tables S1 and S2). In contrast, as previously noted by Stoecklin et al. (2003), in the presence of TPA/Io with or without serum, the TNFα-ARE-reporter RNA level increased at least 10-fold (Figure 1C, lanes 4 and 8). Thus, the drug-induced increase in translation (Figure 1B) reflects mostly stabilization of the mRNA rather than a true translation effect.

Consequently, two translation conditions without TPA/Io (and its DMSO solvent) were chosen for all further studies, and luciferase values were normalized to RNA levels (Figures 1D and S1). (1) In serum-growth conditions, basal translation reflects low mRNA levels. (2) In serum-starved conditions, translation is enhanced without a significant change in mRNA levels, indicating translation activation. Similar results were obtained with the ARE reporter in monocytic THP-1 cells (not shown) and with the 3′-UTR reporter (UTR, Figure 1E), which confirms that the activity of the TNFα ARE is the same in its natural cellular and molecular contexts. Importantly, the translation efficiency of the mt ARE reporter was unchanged between serum-grown and -starved conditions (Figure 1E) even though its RNA abundance was higher than the ARE reporter (Figure S2). Thus, an intact TNFα ARE bears sufficient information to execute regulated translation, and mutating the ARE results in a loss of translation control.

Cell-Cycle Arrest Causes TNFα ARE Translation Upregulation

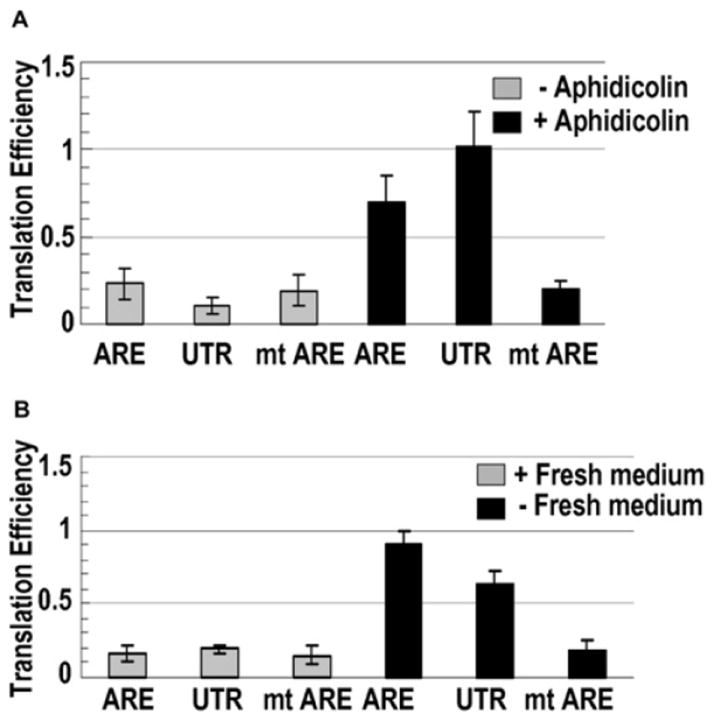

Serum-responsive translation regulation could result from direct effects of serum deprivation or from serum-starvation-induced cell-cycle arrest. We manipulated the cell cycle in ways that avoided removal of serum. First, aphidicolin, a G1/S phase inhibitory drug that induces growth arrest (Jeoung et al., 1995), was added to actively growing HEK293 cells transfected with our reporter constructs for 36 hr. A 3- to 5-fold increase in the translation efficiency of the ARE and UTR reporters, but not of the mt ARE reporter, resulted (compare Figures 2A and 1E). Second, we allowed the cells to grow to saturation, whereupon they arrested the cell cycle (Boonstra, 2003); then, the growth-arrested cells were either maintained or replated in fresh media to induce cell-cycle progression. The arrested cells exhibited a 3- to 5-fold increase in translation efficiency of the ARE and UTR reporters compared to both the mt ARE reporter and the same reporters in cycling cells (compare Figure 2B to Figures 1E and 2A; Table S3 shows the raw numbers). In these two situations, as well as in serum-starved cells, western blots that were probed for Ki67, a cell-cycle marker, revealed the expected decreased level (Figure S3A; Schafer, 1998). Translation activation upon G1/G0 growth arrest (Figures 1, 2, and S3A) and not G2 arrest (Figure S3B) indicates that the TNFα ARE responds to specific cell-cycle cues.

Figure 2. Cell-Cycle Arrest Increases Translation Mediated by the TNFα ARE.

(A) Eighteen hours after transfection as in Figure 1, HEK293 cells were treated with aphidicolin dissolved in DMSO or with DMSO alone for 36 hr before measuring luciferase activities and mRNA levels by RPA. The values in panels (A) and (B) are averages from at least three transfections ± SD.

(B) After transfection, cells were grown for 66 hr to saturation. Then, one set was replated in fresh media; six hours later, luciferase and mRNA levels were assessed. Cell-cycle arrest was validated by western blotting for Ki67 (Figure S3 and Table S3).

Isolation of ARE-Associated, Translation-Activating, and Basal Translation Complexes

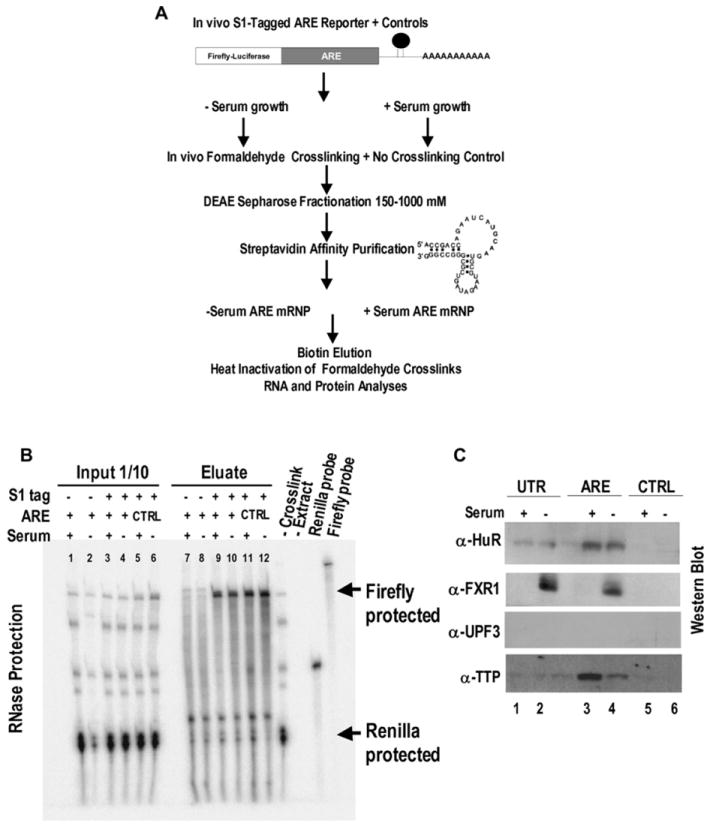

The next step was to compare the composition of the serum-regulated ARE-associated complexes. There are at least two major problems. First, AREs are dynamically bound by factors, some with very rapid off rates that lead to loss upon purification (Park-Lee et al., 2003). Second, during cell-extract preparation, abundant nonspecific RNA-binding proteins can compete off the limiting, endogenous ARE-bound proteins (Mili and Steitz, 2004). Therefore, we used in vivo formaldehyde crosslinking to “freeze” ARE-associated mRNP complexes (Niranjanakumari et al., 2002). Purification of the extracts on streptavidin beads then selected only S1-aptamer-tagged mRNPs (Srisawat and Engelke, 2002; Figure 3A). After reversal of the formaldehyde crosslinks, RNA components of the complexes were examined by RNase protection (Figure 3B), while proteins were identified by mass spectrometry (Figure S4B; Table S4) and western blotting (Figure 3C).

Figure 3. Purification of mRNP Complexes.

(A) After in vivo formaldehyde crosslinking, the S1-tagged ARE construct was purified as described in Experimental Procedures. An S1-tagged CTRL construct, an untagged ARE reporter, and uncrosslinked controls were examined in parallel.

(B) RPA demonstrates enrichment of the ARE and CTRL S1-tagged RNAs (lanes 9–12) in the biotin eluates compared to the nontagged ARE reporter (lanes 7 and 8) and the cotransfected REN internal control. Unmarked bands are heat-induced degradation products of the firefly ARE reporter. –Crosslink (uncrosslinked extract) and –Extract (no sample) served as RPA controls.

(C) Proteins present in crosslinked eluates from the S1-tagged UTR, ARE, and CTRL constructs in the basal translation serum-grown conditions (lanes 1, 3, and 5) were compared to those in the activated serum-starved conditions (lanes 2, 4, and 6) by western blot analysis. α-UPF3 served as control. The unlabeled lane between lanes 2 and 3 was from a TPA-treated UTR sample.

This strategy was applied to both translation conditions for the TNFα ARE and UTR reporters after we confirmed that aptamer tagging did not alter the regulated translation exhibited by untagged reporters in Figures 1, 2, and S4A. Figure 3B shows recovery of about 20% of the aptamer-bearing ARE reporter in the initial HEK293 cell extract in the biotin eluate from the streptavidin beads, whereas untagged reporters and the cotransfected Renilla (untagged) RNA were not selected. Experiments without formaldehyde crosslinking or with the aptamer-tagged CTRL reporter detected nonspecific proteins (Figure S4B).

FXR1 Solubility and mRNA Association Are Regulated by Serum

Western blot analyses revealed the selective enrichment of ARE-binding proteins HuR and TTP in mRNPs formed under both serum conditions on the ARE and UTR compared to CTRL reporters (Figure 3C). In addition, we detected a 65 kDa isoform (a or b in Figure S5A) of FXR1, a recently identified TNFα-ARE-binding and putative translation factor (Garnon et al., 2005), exclusively in ARE-specific complexes (on the ARE or UTR reporter) in cells that had been subjected to serum starvation (Figure 3C). FXR1 was also present in ARE mRNPs that had been isolated from THP-1 monocytes (data not shown). Moreover, antibodies against FXR1 coimmunoprecipitated endogenous TNFα mRNA from crosslinked extracts of monocytes that had been cultured under serum-starved, but not serum-grown, conditions, as revealed by RT-PCR using three primer sets (Figure S6A). Thus, the endogenous TNFα mRNP complex contains FXR1 in a serum-regulated manner identical to our reporters in HEK293 cells.

The presence of FXR1 in the ARE mRNP could reflect serum regulation of its cellular levels. Western blotting revealed multiple isoforms (due to either splicing or modification) of FXR1 in soluble extracts of HEK293 cells, but only when serum starved (Figure 4A, lane 6 versus lane 5). Yet, FXR1 was equally abundant in sonicated whole-cell lysates from serum-grown or -starved conditions (Figure 4A, lower panel), which suggests an alteration in solubility rather than expression. Similar regulation of solubility was previously reported for an FXR1 isoform during muscle differentiation, a process mimicked by serum starvation (Mazroui et al., 2002; Hofmann et al., 2006; Dube et al., 2000).

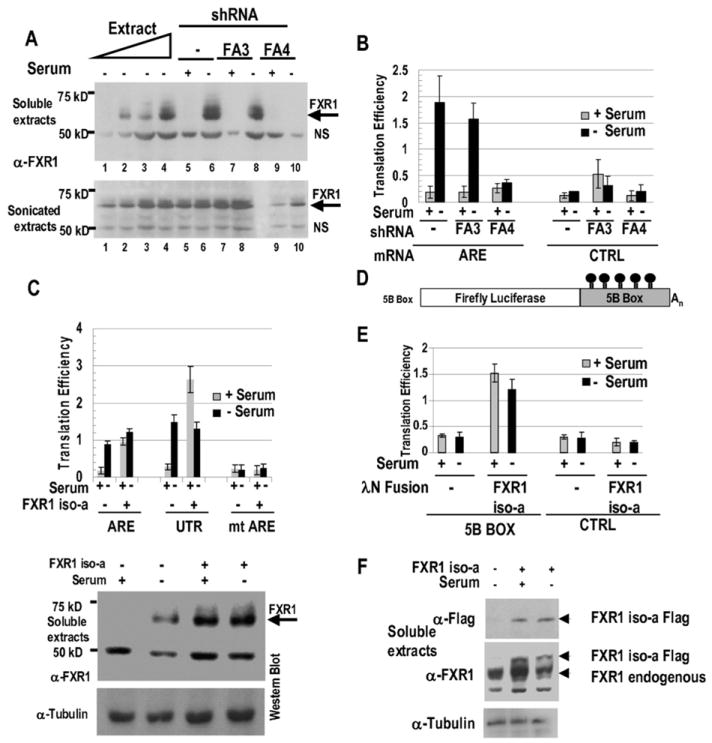

Figure 4. FXR1 Is Required for TNFα-ARE-Mediated Translation Upregulation in Response to Serum Starvation.

(A) Knockdown of FXR1 by shRNA FA4, predicted to target FXR1 iso-a (see Figure S5A), is shown. Western blotting (α-FXR1; described in Jin et al., 2004) reveals FXR1 in the soluble fraction only in serum-starved conditions (upper panel, lanes 1–4, 6, and 8) compared to sonicated total extracts from the same cells (lower panel). Two-fold titrations of the serum-starved extract (lanes 1–4) are compared with extracts (the same amount as in lane 4) from cells grown with serum (+ lanes) or without serum (− lanes) that were either untreated (lanes 5 and 6) or exposed to either shRNA FA3 (lanes 7 and 8) or shRNA FA4 (lanes 9 and 10). NS is a nonspecific band or breakdown product recognized by the anti-FXR1 polyclonal antibody.

(B) Knockdown of FXR1 by shRNA FA4 leads to loss of translation activation of the ARE relative to the CTRL reporter in serum-starved conditions. The values in panels (B), (C), and (E) are averages from at least three transfections ± SD.

(C) Exogenous expression of the isoform, FXR1 iso-a (the most abundant isoform in our cells), increases the translation efficiency of the ARE and UTR reporters but not of the mt ARE in serum-grown conditions. Western blotting (below) demonstrates that exogenous expression of iso-a generates FXR1 in the soluble fraction of serum-grown cells (+ lanes). The band at 50 kDa is nonspecific and is described in (A). Anti-tubulin provided a loading control.

(D) The 5B Box tethering site of 343 nt (Baron-Benhamou et al., 2004) replaces the ARE in the firefly ARE reporter.

(E) Flag-tagged FXR1 iso-a tethered by the λN peptide to the 5B Box reporter activates translation in both serum conditions compared to the CTRL reporter or the empty λN vector.

(F) Western blotting as in (C) reveals similar expression of the λN-peptide- and Flag-tagged FXR1 iso-a in soluble extracts from serum-grown and -starved cells. The middle panel discriminates the Flag-tagged and endogenous FXR1 isoforms. Comparable results were obtained with cells grown to saturation (quiescence).

FXR1 Functions as a Translation Activator

To ask whether FXR1 is essential for translation activation under serum-starvation conditions, we designed two shRNAs (Figure S5A). shRNA FA4 (but not shRNA FA3) knocked down the multiple FXR1 isoforms in serum-starved HEK293 soluble cell extracts by over 75% (arrow in Figure 4A), which suggests that the predominant form present in our cells is FXR1 iso-a. This produced a loss of translation activation of the ARE reporter, while the translation efficiency of the CTRL reporter was unaffected (Figure 4B). Importantly, this effect was rescued by exogenous expression of FXR1 from a clone bearing silent mutations at the shRNA target site (Figure S5B).

Conversely, exogenous expression of FXR1 iso-a (Figure 4C) stimulated translation of both the ARE and UTR reporters compared to mt ARE, but in serum-grown conditions. This unexpected result correlates with the increased levels of soluble FXR1 upon exogenous expression in serum-grown cells (Figure 4C, lower panel). Since soluble FXR1 is already abundant in serum-starved cells, perhaps exogenous expression cannot further enhance translation.

To confirm translation stimulation by FXR1, FXR1 iso-a was fused to a λN peptide to anchor it to the 5B Box luciferase reporter (Figure 4D; Baron-Benhamou et al., 2004); a Flag tag distinguished the λN-fused from endogenous FXR1. Coexpressing the doubly tagged FXR1 iso-a yielded over a 4-fold increase in translation efficiency for the 5B Box reporter compared to the λN vector in both serum-starved and -grown cells (Figure 4E). The λN-tagged FXR1 was equally expressed in soluble extracts in both conditions (Figure 4F). The CTRL reporter was unresponsive to the presence of the λN-tagged FXR1, and cotransfection did not alter RNA levels (Figure S5C). These results confirm a translation upregulatory activity for FXR1 iso-a.

FXR1 Interacts with the MicroRNP Factor, AGO2, under Both Translation Conditions

Drosophila dFMR1 interacts with dAGO1 genetically (Jin et al., 2004) and with dAGO2 biochemically (Caudy et al., 2002; Ishizuka et al., 2002), while interactions with human FXR1 protein have been reported for hAGO1 and hAGO2 (Jin et al., 2004). We therefore asked whether FXR1 and AGO2 proteins interact in vivo in activated versus basal translation conditions. Strikingly, ~30% of AGO2 was recovered in stringently washed α-FXR1 immunoprecipitates from sonicated extracts of cells grown under both serum conditions after formaldehyde cross-linking (Figure 5A, lanes 5 and 6 versus 7 and 8). The interaction was reproducible with RNase (data not shown) and in soluble extracts of serum-starved cells, while in serum-grown soluble extracts FXR1 is discarded during clarification (see Figure 4A), thereby precluding interaction analysis. Additionally, the λN-tagged FXR1 iso-a, which activated translation when tethered to a reporter (Figure 4D), coimmunoprecipitated endogenous AGO2 (Figure 5A, lanes 9 and 10), arguing that the λN tag does not interfere with the protein’s normal associations. These results indicate that FXR1 and AGO2 associate with each other under both serum-grown and -starved conditions.

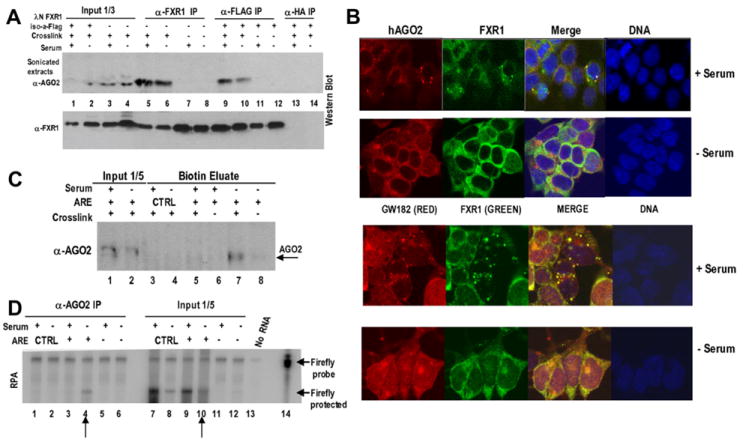

Figure 5. AGO2 Is Present in the ARE Translation Activation Complex.

(A) FXR1 interacts with AGO2 in serum-grown and -starved HEK293 cells. In vivo formaldehyde crosslinking of cells that were untransfected or transfected with the λN-FXR1 iso-a-Flag vector was followed by sonicated cell-extract preparation. Immunoprecipitation of the untransfected sample (lanes 3–8) with α-FXR1 (lanes 5–8) and of the λN-FXR1 iso-a-Flag-transfected sample (lanes 1, 2, and 9–14) with either α-Flag (lanes 9–12) or α-HA (lanes 13 and 14, negative control) was followed by stringent washing. Western blotting (α-AGO2 antibody; Upstate) revealed AGO2 coimmunoprecipitation with α-FXR1 (lanes 5 and 6) or α-Flag (lanes 9 and 10) from crosslinked samples only (lanes 7 and 8 for α-FXR1 IP and lanes 11 and 12 for α-Flag IP-uncrosslinked). The absence of reporters (this Figure) or the presence of ARE, 5B Box, or control reporters did not alter the interaction (data not shown). No RNase (this Figure) or RNase-treated extracts (RNase A and RNase One, data not shown) showed similar interactions.

(B) Confocal immunofluorescence imaging was performed with fixed samples of serum-grown and -starved HEK293 cells stained with α-AGO2, α-FXR1, or α-GW182. TO-PRO-3 (Invitrogen) identified DNA in the nuclei. FXR1 staining was identical using polyclonal antibody from S. Warren or monoclonal antibody (6GB10) from G. Dreyfuss. Standard controls using single antibodies and no primary antibody ensured no artifactual channel overlap/staining (data not shown). Magnified images and details are in Figures S7–S8.

(C) RNPs formed on the S1-tagged ARE and CTRL reporters were isolated as in Figure 3A, which was followed by western analysis of the eluates (lanes 3–8) with α-AGO2. AGO2 appeared specifically in translation activation conditions (compare lanes 5 [serum +] and 7 [serum −]). The extracts (input) from noncrosslinked cells serve as negative controls (lanes 6 and 8), as do eluates from the S1-tagged CTRL reporter (lanes 3 and 4). (D) Anti-AGO2 immunoprecipitates the S1-tagged ARE reporter exclusively from translation activation (serum-starved) conditions (lane 4 versus lane 3). Immunoprecipitation was performed as in (A) on extracts of crosslinked cells. The immunoprecipitates (lanes 1–6) and inputs (extracts, lanes 7–12) were analyzed by RPA. Cells expressing the CTRL (lanes 1 and 2) reporter served as a negative control.

Subcellular Colocalization of FXR1 and AGO2

AGO2 is known to localize to P bodies (Liu et al., 2005a), GW bodies (Jakymiw et al., 2005), and stress granules (Leung et al., 2006), which are cytoplasmic granules associated with translation silencing and mRNA decay. FXR1 has also been reported in cytoplasmic granules (Mazroui et al., 2002; Hofmann et al., 2006). To ask whether these are the same bodies, we performed immunofluorescence studies with antibodies to AGO2 and to FXR1 (Figures 5B, S7, and S8). A significant fraction of FXR1 and AGO2 appeared in the same or closely associated foci in HEK293 cells in the translationally basal serum-grown conditions (Figures 5B, top panels, and S7A–S7C). These particular bodies did not colocalize with hDCP1A (Figures S7F and S7G), a P-body marker (Kedersha et al., 2005; Andrei et al., 2005); this is consistent with recent reports that only up to 1.3% of AGO2 is present in P bodies (Leung et al., 2006). Interestingly, the FXR1/AGO2 bodies do partially colocalize with GW182 (Figures 5B, lower panels, and S8A–S8D), a protein previously reported to interact with AGO2 (Jakymiw et al., 2005; Liu et al., 2005b). GW bodies are cell-cycle regulated, and they grow in size and number through the cell cycle but disappear upon mitosis or in quiescent or growth-arrest conditions (Yang et al., 2004; Lian et al., 2006).

In contrast, in serum-starved cells, FXR1 and AGO2 were diffusely distributed throughout the cytoplasm or appeared in very small bodies (Figures 5B, – serum, S7D, and S7E), while the P-body marker hDCP1A remained in large bodies (Figure S7G). The disappearance of these distinct FXR1/AGO2 bodies that partially overlap with GW bodies interestingly coincides with translation activation. The absence of discrete bodies and the diffuse cytoplasmic colocalization of FXR1 and AGO2 under serum-starved conditions may be important for ARE-directed translation upregulation.

AGO2 Is a Component of the TNFα ARE-RNP in Serum-Starved Conditions

Interaction and cytoplasmic colocalization of FXR1 and AGO2 suggested that AGO2 may be present not only in microRNPs (Valencia-Sanchez et al., 2006) but also in the TNFα ARE-mRNP under translation activation conditions. We used western analysis to probe for AGO2 in the S1 aptamer-purified in vivo crosslinked complexes from serum-grown and -starved cells (Figure 5C). Significantly, AGO2 was present in the ARE complex exclusively from serum-starved conditions (lane 7). RNPs that formed on the CTRL mRNA did not contain AGO2 (lanes 3 and 4), nor did the ARE mRNPs that were isolated from serum-grown cells (lane 5) or without crosslinking (lane 8).

Specific association of AGO2 with the TNFα ARE-RNP was confirmed by anti-AGO2 coimmunoprecipitation of the TNFα ARE reporter from serum-starved, but not from serum-grown, cell extracts (Figure 5D, lane 4 versus lane 3). The CTRL (non-ARE-containing) reporter (lanes 1 and 2) was not precipitated. Furthermore, anti-AGO2 coimmunoprecipitated the endogenous TNFα mRNA from crosslinked extracts of monocytes grown under serum-starved (but not serum-grown) conditions, as analyzed by RT-PCR using three primer sets (Figure S6B). Together, these results argue for a role for AGO2 in ARE-directed translation activation.

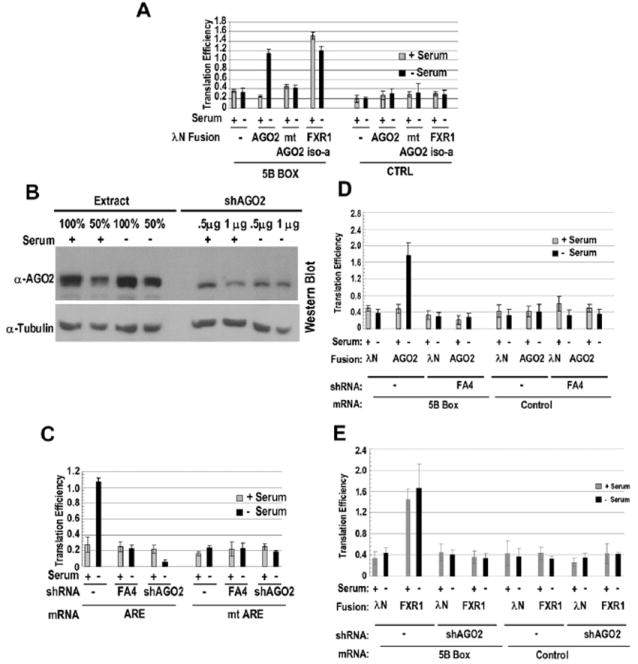

AGO2 Is a Translation Activator in Serum-Starved Conditions

To test whether AGO2 has a direct serum-starvation-specific role in translation upregulation, we tethered AGO2 via a fused λN peptide to the luciferase reporter containing 5B Boxes (see Figure 4D). Assays of translation efficiency in both serum-grown and -starved conditions revealed a 5-fold upregulation of translation (Figure 6A) in only serum-starved cells, which is consistent with AGO2’s interaction with FXR1 (Figure 5A). In contrast, in serum-grown cells, tethering AGO2 produced a moderate 1.8-fold repression, as previously reported (Liu et al., 2005b; Pillai et al., 2004). Tethering a mutant AGO2 protein (mt AGO2), which is unable to effect translation repression (Pillai et al., 2004), did not increase translation efficiency (Figure 6A). RNase-protection analyses demonstrated that the reporter RNA levels were unchanged (Figure S5C; Pillai et al., 2004). We conclude that AGO2 functions as a translation activator in response to serum starvation, mediating translation upregulation when tethered to an mRNA reporter.

Figure 6. AGO2 Activates Translation Mediated by TNFα ARE in Response to Serum Starvation and Requires FXR1 to Function as a Translation Activator.

(A) Tethering AGO2 upregulates translation in response to serum starvation. A mutant form of AGO2 (mt AGO2; Pillai et al., 2004) and the CTRL reporter (Figure 1A) without the 5B Boxes provided negative controls. FXR1 iso-a (Figure 4E) served as a positive control. The values in panels (A), (C), (D), and (E) are averages from at least three transfections ± SD.

(B) Western blot done using α-AGO2 of soluble HEK293 extracts to assess knockdown by two shRNAs used together at either 0.5 μg or 1.0 μg plasmid DNA (shAGO2; see Experimental Procedures) is shown. Two extract concentrations and α-tubulin antibody provided controls.

(C) Comparison of the effects of no shRNA (−), FXR1 shRNA (FA4), or AGO2 shRNA (shAGO2) on the translation efficiencies of the ARE and mt ARE reporters under serum+ and serum– conditions shows that both FXR1 and AGO2 are required for upregulation.

(D) FXR1 is essential for translation upregulation mediated by tethered AGO2. AGO2 or the λN-tag vector (as a control) was tethered to the firefly reporter in control or FXR1 shRNA (FA4)-treated cells under serum-grown and -starved conditions.

(E) AGO2 is essential for translation upregulation mediated by tethered FXR1. λN-tagged FXR1 iso-a or the λN-tag vector was transfected with the firefly reporter bearing 5B Boxes in control (−) or AGO2 shRNA (shAGO2)-treated cells under serum-grown and -starved conditions. Comparable results were obtained with cells grown to saturation (quiescence).

To confirm that AGO2 is essential for translation activation via the TNFα ARE, we performed shRNA knockdown of AGO2 followed by luciferase assays with our ARE reporters in serum-grown and -starved conditions. AGO2 levels do not change with serum conditions and, unlike FXR1 levels, are similar in sonicated and gently clarified soluble extracts (Figure 6B), although we do centrifuge out a considerable amount when preparing polysome extracts (Figure 7B). Upon partial reduction of AGO2 levels with shAGO2 (Figure 6B), 5-fold lower translation efficiency was observed for the TNFα ARE reporter (Figure 6C). Loss of translation stimulation was similar for the ARE and UTR reporters (data not shown), which suggests that the TNFα ARE mediates AGO2 recruitment to the 3′-UTR and that AGO2 is essential for translation upregulation.

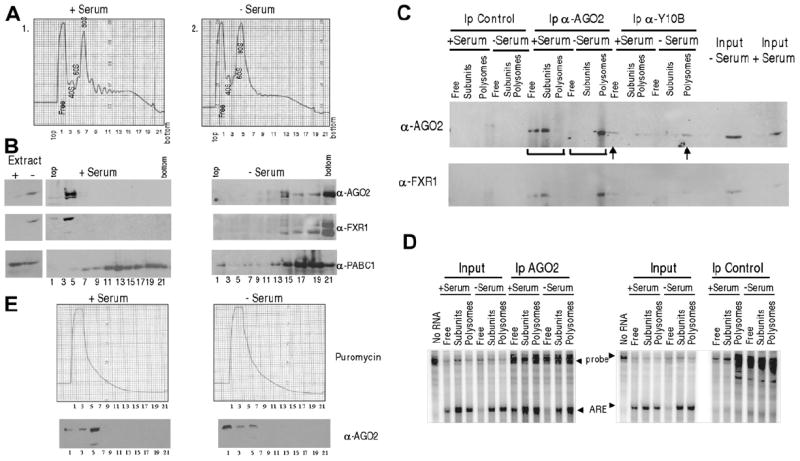

Figure 7. Serum Starvation Activates Translation by Relocalization of AGO2-Bound mRNPs to Polysomes.

(A) Polysome profiles of extracts from (1) serum-grown or (2) serum-starved cells transfected with the TNFα ARE are shown.

(B) Western analysis of fractions across the profiles using antibodies against AGO2, FXR1, and PABC1 as a control is shown. FXR1 mobility becomes heterogeneous (modifications or protein degradation) upon serum starvation. Since the lysates were clarified, the majority of FXR1 and AGO2 in +serum are removed as large complexes, including those in large foci (Figures 5B and S7–S8), prior to gradient analysis (verified by the Extract lanes marked +serum and −serum).

(C) Anti-AGO2 (marked by brackets) and Y10B (arrows) immunoprecipitations were performed on the Free RNP (fractions 1–2), subunits (fractions 3–9, including monosomes), and polysomes (fractions 10–22), followed by western analyses using α-AGO2 and -FXR1 antibodies.

(D) RPA for the ARE-reporter RNA was performed on the pooled fraction as in (C).

(E) Western analysis of polysome profiles from serum-grown and -starved cells demonstrates a complete shift of AGO2 from polysomes (compare with B, −Serum lanes) to a single slowly sedimenting peak upon 1 mM puromycin treatment for 3 hr at 37°C. Puromycin causes an equal proportion of AGO2 to be clarified from extracts of both serum conditions.

To determine whether an interaction between FXR1 and AGO2 is necessary for serum-starvation-regulated translation activation by tethered AGO2, we first performed the AGO2-tethering experiment in an FXR1 knockdown background. If FXR1 recruits AGO2 directly or indirectly to the ARE-containing message, then the tethered AGO2 should exhibit serum-starvation-regulated translation activation even in the absence of FXR1. However, as shown in Figure 6D, 75% knockdown of FXR1 (data not shown) led to a loss of translation activation by tethered AGO2 under serum-starvation conditions, which indicates either that interaction between FXR1 and AGO2 is necessary for translation activation or that FXR1 is required at a downstream step. Conversely, knockdown of AGO2 decreased translation activation by tethered FXR1 (Figure 6E). These data suggest that AGO2 and FXR1 function together to activate translation in response to growth arrest.

Serum Starvation Activates Translation by Relocalization of AGO2-Bound mRNPs to Heavy Polysomes

To demonstrate that the ARE-reporter RNA is bound by AGO2 when recruited to polysomes in translation activation conditions, we performed sucrose gradient analyses of soluble extracts from cells grown in serum or with serum starvation (Figure 7). For two reasons, the cells were not exposed to cycloheximide, a reagent commonly used to freeze polysomes: Mazroui et al. (2002) showed that FXR1 granules (Figure 5B) are disrupted by cycloheximide, and Kedersha et al. (2005) observed a decrease in P-body and stress-granule formation, which suggests that cycloheximide may affect the normal distribution of AGO2. We examined individual fractions from the gradients or pooled them into Free RNP (fractions 1–2), subunits (fractions 3–9), and polysomes (fractions 10–22) and assessed the distribution of AGO2, FXR1, and the reporter RNA both with and without puromycin treatment.

Figure 7D (left panel) reveals that the TNFα ARE reporter coimmunoprecipitated by anti-AGO2 indeed shifts down in the gradient to concentrate in heavy polysomes in serum-starved versus -grown cells. There is less AGO2 and FXR1 in the total profile (Figure 7B; Extract, compare + with – lanes) of serum-grown cells, likely due to the removal of large complexes by clarification, as observed earlier for FXR1 (Figure 4A); both proteins concentrate in the Free RNP fractions (left panels). In serum-starved cells, the amounts of AGO2 and FXR1 are higher, which correlates with the absence of foci and the solubility of FXR1 (Figure 4A). Figure 7C (upper and lower panels marked by brackets) shows that FXR1 also coimmuno-precipitates with anti-AGO2 in the polysome fraction of serum-starved cells, while an antibody that interacts with ribosomal RNA (Y10B; Lerner et al., 1981) confirms that this AGO2 is ribosome associated (Figure 7C, arrows). Puromycin treatment, which has been demonstrated to increase both P bodies and stress granules (Kedersha et al., 2005), released AGO2 from polysomes along with collapsing the polysomes from both serum-starved and -grown conditions (Figure 7E); note that the detection of comparable low amounts of AGO2 suggests that an equal portion was clarified from extracts of serum-grown versus -starved cells treated with puromycin. We conclude that the mechanism of translation activation by the FXR1/AGO2 ARE complex involves recruitment of the TNFα mRNP to heavy polysomes upon serum starvation.

DISCUSSION

We set out to elucidate how AREs regulate translation by examining RNPs assembled in vivo on the TNFα ARE under conditions where the translation output relative to mRNA levels was enhanced. We first established that the TNFα ARE—but not a mutant ARE—mediates upregulation of translation efficiency upon serum starvation in response to cell-cycle cues. Affinity purification surprisingly revealed the presence of two proteins, FXR1 and AGO2, which were previously considered to be repressive, in the ARE-mRNP formed under serum-starved conditions. Their interdependent translation stimulatory activity was confirmed both by reducing their cellular levels and by tethering them to a luciferase reporter in the absence of the ARE. Our results underscore the versatility of RNA-binding proteins in effecting both positive and negative outcomes in response to different cellular environments.

The TNFα ARE Functions as a Translation Upregulatory Element by Recruiting FXR1 and AGO2

The ability of AREs to regulate both translation and mRNA stability (Espel, 2005; Kontoyiannis et al., 1999) may result primarily from differences in the signals received. How might the TNFα ARE respond to such signals? Two possible molecular models exist: the ARE may recruit distinct complexes to produce alternate outcomes or a common ARE-binding complex may be modulated by the addition or deletion of specific effectors. Our data support the latter model since ARE-stability factors such as TTP and HuR are present in all conditions, but FXR1 and AGO2 are recruited only upon serum starvation (Figures 3C and 5C).

Recently, both HuR and TTP were implicated in microRNP-mediated translation repression through mRNA relocalization into P bodies (Bhattacharyya et al., 2006) or through interactions with AGO2 that induce mRNA decay (Jing et al., 2005). HuR was further suggested to be an agent alleviating microRNA-mediated repression in a stress response to amino-acid starvation (Bhattacharyya et al., 2006). In contrast, we find that tethering HuR to our 5B Box reporter increases translation efficiency less than 2-fold (Figure S9), arguing that the upregulation studied here is distinct. Only upon serum starvation does FXR1 interaction with AGO2 remodel the ARE complex to enhance rather than repress translation (Figures 6A, 6D, and 6E; Jin et al., 2004).

FXR1 Is a Cell-Cycle-Sensitive Translation Regulator

Since translation activation can be achieved either by serum starvation leading to FXR1 association with the ARE or by tethering FXR1 to the mRNA (Figures 3-4), mRNA association may be the decisive switch that converts FXR1 into a translation activator. The ability of FXR1 to associate with the TNFα ARE (Garnon et al., 2005) could be regulated by either its modification or that of other ARE-bound factors. Exogenous expression of FXR1, which—like tethering—activates translation irrespective of the signals present (Figure 4C), correlates with an increase in soluble FXR1 (Figures 4C, lower panel, and 4F). Thus, FXR1 solubility may be critical in altering the translation outcome in response to serum starvation.

In serum-grown cells, FXR1 appears in cytoplasmic bodies (Figures 5B and S7–S8) that are reported to be associated with translation silencing (Mazroui et al., 2002; Hofmann et al., 2006). The nature of these bodies is currently unclear, but it seems unlikely that they are P bodies because they do not completely colocalize with the P-body marker hDCP1A (Figures S7F and S7G). Although P bodies and GW bodies overlap and have been considered the same bodies, there is growing evidence for distinct subsets (Eystathioy et al., 2003). GW bodies are cell-cycle-regulated and disappear on growth arrest (Yang et al., 2004; Lian et al., 2006), as we observe for FXR1 bodies (Figures 5B and S8, compare +serum with −serum), while P bodies remain (Figure S7G). Interestingly, AGO proteins were recently shown to colocalize with GW bodies in a similar cell-cycle-regulated manner (Ikeda et al., 2006).

Under serum-grown conditions, FXR1 may function as a translation repressor through its interaction with AGO proteins (Figure 5A; Liu et al., 2005a; Caudy et al., 2002). Indeed, macrophages from FXR1 knockout mice exhibit increased translation of a TNFα ARE reporter when compared to those from wild-type mice (Garnon et al., 2005).

AGO2 Activates Translation in Response to Serum Starvation

AGO2 (also called eIF2C2) was originally identified as an enhancer of in vitro translation through stimulation of ternary complex formation and stability (Zou et al., 1998; Roy et al., 1988). Aubergine, a Drosophila member of the PIWI subfamily of Argonaute-related proteins, is a translation repressor and RNAi factor during early oogenesis but later acts as a translation activator (Wilhelm and Smibert, 2005). Tethering AGO2 yields a moderate 1.8-fold repression in HEK293 cells in serum-grown conditions (Figure 6A), which is similar to observations in HeLa cells (Liu et al., 2005b). Up to 5-fold repression was reported by Pillai et al. (2004), but using 5-fold more AGO2 plasmid and the transfection reagent Lipofectamine, which has recently been observed to induce toxicity and alter expression (unpublished data; Barreau et al., 2006).

Tethering AGO2, unlike FXR1, upregulates translation only in the absence of serum (Figure 6A), which suggests that AGO recruitment to the mRNA is not the step that decides outcome. Since AGO2 tethering failed to activate translation in an FXR1 knockdown background (Figure 6D) and vice versa (Figure 6E), interaction between FXR1 and AGO2 (direct or indirect) is required for translation activation.

FXR1 and AGO2 associate with cytoplasmic foci that partially colocalize in serum-grown conditions (Figures 5B and S7A–S7C). Under serum-starvation conditions, where AGO2 and FXR1 become bound to the ARE-containing message (Figures 3C and 5C–5D), they are more diffusely present in the cytoplasm or in smaller foci, which possibly accounts for their transformation into translation upregulatory effectors (Figures 5B, –Serum panels, S7D, S7E, S7G, and S8, lower panels of A, B, and D).

Jing et al. (2005) previously demonstrated that AGO2 interacts with TTP and miR16-1 to induce decay of a TNFα 3′-UTR reporter mRNA. The interaction involved an AU-rich nonamer present elsewhere in the TNFα 3′-UTR, not the canonical 34 nt ARE studied here. We confirmed that their complex is distinct in that miR16 does not associate specifically with our ARE mRNP (Figure S10A), nor does miR16 knockdown affect translation (Figures S10B and S10C). The involvement of a microRNA in translation activation remains to be explored. Our data indicate that AGO2, like FXR1, plays a dual role on the TNFα 3′-UTR and exerts translation regulation through the ARE or microRNA-mediated decay through a distinct 3′-UTR element (Jing et al., 2005).

Mechanism of ARE-Mediated Translation Regulation

Polysome profile analyses of soluble cytoplasmic extracts revealed that translation upregulation correlates with a shift of the FXR1/AGO2 ARE mRNP complex from the free/subunit fractions to heavier polysomes (Figures 7B–7E) upon serum starvation. In this condition, most of the AGO2 and FXR1 appear diffuse or are present in small foci (Figure 5B) that sediment to the bottom of the gradient. Conversely, in serum-grown cells, most FXR1 and AGO2 are removed by extract clarification (demonstrated by the Extract lanes, Figure 7B), presumably because they exist in larger insoluble complexes that include the foci observed in Figures 5B and S7–S8. The polysome experiments (Figure 7) were performed without agents, like cycloheximide, that appear to disrupt or diminish these foci (Mazroui et al., 2002; Kedersha et al., 2005) and might alter AGO2 localization. In contrast, recent studies demonstrate AGO proteins and microRNP complexes on polysomes in growing cells (Nelson et al., 2004; Nottrott et al., 2006; Maroney et al., 2006) using cycloheximide or emetine. Our results suggest that growth arrest decreases GW/FXR1/AGO2 foci and promotes ARE-specific polysome association of the AGO2-bound mRNP complex. The molecular basis for transformation of the ARE mRNP into a translation activator complex that enables upregulated expression of cytokine messages such as TNFα remains to be elucidated.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

For detailed procedures see Supplemental Data.

Cell Culture

HEK293 cells and THP-1 monocytes that were maintained in DMEM or RPMI, respectively, with 10% FBS were transfected with Trans-It 293 kit (MirusBio) for HEK293 or Nucleofector (Amaxa) for THP-1 per the manufacturer’s instructions.

Extract Preparation and Purification of S1-Tagged mRNP

Cells transfected with the S1-tagged constructs and grown in various serum conditions (Figure 3) were incubated with 0.2% formaldehyde in PBS for 10 min at 37°C (Niranjanakumari et al., 2002). Cells were lysed (150 mM KCl, 10 mM Hepes 7.4, 3 mM MgCl2, 2 mM DTT, 10% glycerol, and 0.5% NP-40) for 10 min on ice, sonicated and clarified by centrifugation at 2000 g for 5 min, precleared with avidin beads, followed by DEAE sepharose fractionation (150–1000 mM KCl). The 1 M fraction, which was enriched for the firefly RNA, was then bound to streptavidin for 4 hr; washed ten times with a salt gradient up to 300 mM KCl in the binding buffer with tRNA, glycogen, and 2% NP-40; and eluted for 1 hr with 5 mM biotin (Srisawat and Engelke, 2002). After heat inactivation at 65°C for 45 min (Niranjanakumari et al., 2002), the RNA and proteins were assayed.

Immunofluorescence

Laser-scanning confocal immunofluorescence imaging was performed using an inverted Axiovert 200 LSM 510 Meta confocal microscope (Zeiss) at the Yale Cell and Confocal Microscopy and Imaging Facility. Briefly, cells were fixed with 2% formaldehyde, permeabilized with methanol or 0.1% Tween 20, blocked, incubated, and washed with 1% normal goat serum in PBS.

RNA Analyses

Northern blots were performed on 10 μg total RNA, run on a 1% formaldehyde gel, and probed with 32P-labeled RNAs complementary to the 3′ end of the coding region of firefly (−330 nt from the stop codon) or of Renilla (−90 nt from the stop codon; Figure 1). For all other figures, RPA was performed using the same probes, and the protected samples were run on 6% PAGE, dried, and quantitated by a Storm 840 phosphorimager (Molecular Dynamics).

Translation Assays

Luciferase activities were measured using a TD 20/20n (Turner BioSystems) and the Dual Luciferase Assay System (Promega) per manufacturers’ instructions. The firefly to Renilla luciferase ratio was further normalized for RNA levels (see Figures 1A and S1; Tables S1–S3).

Polysome analysis was performed as described in Ceman et al. (2003).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to S. Warren, G. Dreyfuss, Jens Lykke-Andersen, E.W. Khandjian, and M. Hentze for reagents. We thank A. Alexandrov, N. Kolev, K. Tycowski, and V. Fok for their review of the manuscript and A. Miccinello for secretarial assistance. This work was supported by NIH grant GM26154 to J.A.S. J.A.S. is an investigator of Howard Hughes Medical Institute. S.V. is supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Cancer Research Institute.

Footnotes

Supplemental Data include ten figures, four tables, Experimental Procedures, and References and can be found with this article online at http://www.cell.com/cgi/content/full/128/6/1105/DC1/.

References

- Andersson K, Sundler R. Signalling to translational activation of tumour necrosis factor-alpha expression in human THP-1 cells. Cytokine. 2000;12:1784–1787. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2000.0784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrei MA, Ingelfinger D, Heintzmann R, Achsel T, Rivera-Pomar R, Luhrmann R. A role for eIF4E and eIF4E-transporter in targeting mRNPs to mammalian processing bodies. RNA. 2005;11:717–727. doi: 10.1261/rna.2340405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakheet T, Frevel M, Williams BR, Greer W, Khabar KS. ARED: human AU-rich element-containing mRNA database reveals an unexpectedly diverse functional repertoire of encoded proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:246–254. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balkwill F. Tumor necrosis factor or tumor promoting factor? Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2002;13:135–141. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(01)00020-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Benhamou J, Gehring NH, Kulozik AE, Hentze MW. Using the lambdaN peptide to tether proteins to RNAs. Methods Mol Biol. 2004;257:135–154. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-750-5:135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barreau C, Dutertre S, Paillard L, Osborne B. Liposome-mediated RNA transfections should be used with caution. RNA. 2006;12:1790–1793. doi: 10.1261/rna.191706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya SN, Habermacher R, Martine U, Closs EI, Filipowicz W. Relief of microRNA-mediated translational repression in human cells subjected to stress. Cell. 2006;125:1111–1124. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boonstra J. Progression through the G1-phase of the on-going cell cycle. J Cell Biochem. 2003;90:244–252. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan CM, Steitz JA. HuR and mRNA stability. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2001;58:266–277. doi: 10.1007/PL00000854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer G. Messenger RNA decay during aging and development. Ageing Res Rev. 2002;1:607–625. doi: 10.1016/s1568-1637(02)00023-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks SA, Connolly JE, Rigby WF. The role of mRNA turnover in the regulation of tristetraprolin expression: evidence for an extracellular signal-regulated kinase-specific, AU-rich element-dependent, autoregulatory pathway. J Immunol. 2004;172:7263–7271. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.12.7263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carballo E, Lai WS, Blackshear PJ. Feedback inhibition of macrophage tumor necrosis factor-alpha production by tristetraprolin. Science. 1998;281:1001–1005. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5379.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caudy AA, Myers M, Hannon GJ, Hammond SM. Fragile X-related protein and VIG associate with the RNA interference machinery. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2491–2496. doi: 10.1101/gad.1025202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceman S, O’Donnell WT, Reed M, Patton S, Pohl J, Warren ST. Phosphorylation influences the translation state of FMRP-associated polyribosomes. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:3295–3305. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube M, Huot ME, Khandjian EW. Muscle specific fragile X related protein 1 isoforms are sequestered in the nucleus of undifferentiated myoblast. BMC Genet. 2000;1:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espel E. The role of the AU-rich elements of mRNAs in controlling translation. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2005;16:59–67. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eystathioy T, Jakymiw A, Chan ELK, Seraphin B, Cougot N, Fritzler M. The GW182 protein colocalizes with mRNA degradation associated proteins hDcp1 and hLsm4 in cytoplasmic GW bodies. RNA. 2003;9:1171–1173. doi: 10.1261/rna.5810203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnon J, Lachance C, Di Marco S, Hel Z, Marion D, Ruiz MC, Newkirk MM, Khandjian EW, Radzioch D. Fragile X-related protein FXR1P regulates proinflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor expression at the post-transcriptional level. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:5750–5763. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401988200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray NK, Wickens M. Control of translation initiation in animals. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1998;14:399–458. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.14.1.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haskill S, Johnson C, Eierman D, Becker S, Warren K. Adherence induces selective mRNA expression of monocyte mediators and proto-oncogenes. J Immunol. 1988;140:1690–1694. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann I, Casella M, Schnolzer M, Schlechter T, Spring H, Franke WW. Identification of the junctional plaque protein plakophilin 3 in cytoplasmic particles containing RNA-binding proteins and the recruitment of plakophilins 1 and 3 to stress granules. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:1388–1398. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-08-0708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda K, Satoh M, Pauley KM, Fritzler MJ, Reeves WH, Chan EK. Detection of the argonaute protein Ago2 and micro-RNAs in the RNA induced silencing complex (RISC) using a monoclonal antibody. J Immunol Methods. 2006;317:38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2006.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizuka A, Siomi MC, Siomi H. A Drosophila fragile X protein interacts with components of RNAi and ribosomal proteins. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2497–2508. doi: 10.1101/gad.1022002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakymiw A, Lian S, Eystathioy T, Li S, Satoh M, Hamel JC, Fritzler MJ, Chan EK. Disruption of GW bodies impairs mammalian RNA interference. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:1267–1274. doi: 10.1038/ncb1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeoung DI, Tang B, Sonenberg M. Effects of tumor necrosis factor-alpha on antimitogenicity and cell cycle-related proteins in MCF-7 cells. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:18367–18373. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.31.18367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin P, Zarnescu DC, Ceman S, Nakamoto M, Mowrey J, Jongens TA, Nelson DL, Moses K, Warren ST. Biochemical and genetic interaction between the fragile X mental retardation protein and the microRNA pathway. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:113–117. doi: 10.1038/nn1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing Q, Huang S, Guth S, Zarubin T, Motoyama A, Chen J, Di Padova F, Lin SC, Gram H, Han J. Involvement of microRNA in AU-rich element-mediated mRNA instability. Cell. 2005;120:623–634. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kedersha N, Stoecklin G, Ayodele M, Yacono P, Lykke-Andersen J, Fitzler MJ, Scheuner D, Kaufman RJ, Golan DE, Anderson P. Stress granules and processing bodies are dynamically linked sites of mRNP remodeling. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:871–884. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200502088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick LL, McIlwain KA, Nelson DL. Alternative splicing in the murine and human FXR1 genes. Genomics. 1999;59:193–202. doi: 10.1006/geno.1999.5868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick LL, McIlwain KA, Nelson DL. Comparative genomic sequence analysis of the FXR gene family: FMR1, FXR1, and FXR2. Genomics. 2001;78:169–177. doi: 10.1006/geno.2001.6667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontoyiannis D, Pasparakis M, Pizarro TT, Cominelli F, Kollias G. Impaired on/off regulation of TNF biosynthesis in mice lacking TNF AU-rich elements: implications for joint and gut-associated immunopathologies. Immunity. 1999;10:387–398. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80038-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner EA, Lerner MR, Janeway CA, Jr, Steitz JA. Monoclonal antibodies to nucleic acid-containing cellular constituents: Probes for molecular biology and autoimmune disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:2737–2741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.5.2737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung AK, Calabrese JM, Sharp PA. Quantitative analysis of Argonaute protein reveals microRNA-dependent localization to stress granules. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:18125–18130. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608845103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian S, Jakymiw A, Eystathioy T, Hamel JC, Fritzler MJ, Chan EK. GW bodies, microRNAs and the cell cycle. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:242–245. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.3.2410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Carmell MA, Rivas FV, Marsden CG, Thomson JM, Song JJ, Hammond SM, Joshua-Tor L, Hannon GJ. Argonaute2 is the catalytic engine of mammalian RNAi. Science. 2004;305:1437–1441. doi: 10.1126/science.1102513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Valencia-Sanchez MA, Hannon GJ, Parker R. MicroRNA-dependent localization of targeted mRNAs to mammalian P bodies. Nat Cell Biol. 2005a;7:719–723. doi: 10.1038/ncb1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Rivas FV, Wohlschlegel J, Yates JR, III, Parker R, Hannon GJ. A role for the P-body component GW182 in microRNA function. Nat Cell Biol. 2005b;7:1161–1166. doi: 10.1038/ncb1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maroney PA, Yu Y, Fisher J, Nilsen TW. Evidence that microRNAs are associated with translating messenger RNAs in human cells. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:1102–1107. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazan-Mamczarz K, Galban S, De Silanes IL, Martindale JL, Atasoy U, Keene JD, Gorospe M. RNA-binding protein HuR enhances p53 translation in response to ultraviolet light irradiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:8354–8359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1432104100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazroui R, Huot ME, Tremblay S, Filion C, Labelle Y, Khandjian EW. Trapping of messenger RNA by Fragile X Mental Retardation protein into cytoplasmic granules induces translation repression. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:3007–3017. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.24.3007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meister G, Landthaler M, Patkaniowska A, Dorsett Y, Teng G, Tuschl T. Human Argonaute2 mediates RNA cleavage targeted by miRNAs and siRNAs. Mol Cell. 2004;15:185–197. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mientjes EJ, Willemsen R, Kirkpatrick LL, Nieuwenhuizen IM, Hoogeveen-Westerveld M, Verweij M, Reis S, Bardoni B, Hoogeveen AT, Oostra BA, Nelson DL. Fxr1 knockout mice show a striated muscle phenotype: implications for Fxr1p function in vivo. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:1291–1302. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mili S, Steitz JA. Evidence for reassociation of RNA-binding proteins after cell lysis: implications for the interpretation of immunoprecipitation analyses. RNA. 2004;10:1692–1694. doi: 10.1261/rna.7151404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moneo V, del Valle GM, Link W, Carnero A. Overex-pression of cyclin D1 inhibits TNF-induced growth arrest. J Cell Biochem. 2003;89:484–499. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson PT, Hatzigeorgiou AG, Mourelatos Z. miRNP:mRNA association in polyribosomes in a human neuronal cell line. RNA. 2004;10:387–394. doi: 10.1261/rna.5181104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niranjanakumari S, Lasda E, Brazas R, Garcia-Blanco MA. Reversible cross-linking combined with immunoprecipitation to study RNA-protein interactions in vivo. Methods. 2002;26:182–190. doi: 10.1016/S1046-2023(02)00021-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nottrott S, Simard MJ, Richter JD. Human let-7a miRNA blocks protein production on actively translating polyribosomes. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:1108–1114. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman F, Jarrous N, Ben Asouli Y, Kaempfer R. A cis-acting element in the 3′-untranslated region of human TNF-alpha mRNA renders splicing dependent on the activation of protein kinase PKR. Genes Dev. 1999;13:3280–3293. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.24.3280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park-Lee S, Kim S, Laird-Offringa IA. Characterization of the interaction between neuronal RNA-binding protein HuD and AU-rich RNA. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:39801–39808. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307105200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillai RS, Artus CG, Filipowicz W. Tethering of human AGO proteins to mRNA mimics the miRNA-mediated repression of protein synthesis. RNA. 2004;10:1518–1525. doi: 10.1261/rna.7131604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillai RS, Bhattacharyya SN, Artus CG, Zoller T, Cougot N, Basyuk E, Bertrand E, Filipowicz W. Inhibition of translational initiation by Let-7 MicroRNA in human cells. Science. 2005;309:1573–1576. doi: 10.1126/science.1115079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomorski P, Watson JM, Haskill S, Jacobson KA. How adhesion, migration, and cytoplasmic calcium transients influence interleukin-1beta mRNA stabilization in human monocytes. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 2004;57:143–157. doi: 10.1002/cm.10159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy AL, Chakrabarti D, Datta B, Hileman RE, Gupta NK. Natural mRNA is required for directing Met-tRNA(f) binding to 40S ribosomal subunits in animal cells: involvement of Co-eIF-2A in natural mRNA-directed initiation complex formation. Biochemistry. 1988;27:8203–8209. doi: 10.1021/bi00421a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer KA. The cell cycle: a review. Vet Pathol. 1998;35:461–478. doi: 10.1177/030098589803500601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirenko OI, Lofquist AK, DeMaria CT, Morris JS, Brewer G, Haskill JS. Adhesion-dependent regulation of an A+U-rich element-binding activity associated with AUF1. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:3898–3906. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.7.3898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srisawat C, Engelke DR. RNA affinity tags for purification of RNAs and ribonucleoprotein complexes. Methods. 2002;26:156–161. doi: 10.1016/S1046-2023(02)00018-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoecklin G, Ming XF, Looser R, Moroni C. Somatic mRNA turnover mutants implicate tristetraprolin in the interleukin-3 mRNA degradation pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:3753–3763. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.11.3753-3763.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoecklin G, Lu M, Rattenbacher B, Moroni C. A constitutive decay element promotes tumor necrosis factor alpha mRNA degradation via an AU-rich element-independent pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:3506–3515. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.10.3506-3515.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoecklin G, Stubbs T, Kedersha N, Wax S, Rigby WF, Blackwell TK, Anderson P. MK2-induced tristetraprolin: 14–3-3 complexes prevent stress granule association and ARE-mRNA decay. EMBO J. 2004;23:1313–1324. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valencia-Sanchez MA, Liu J, Hannon GJ, Parker R. Control of translation and mRNA degradation by miRNAs and siRNAs. Genes Dev. 2006;20:515–524. doi: 10.1101/gad.1399806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm JE, Smibert CA. Mechanisms of translational regulation in Drosophila. Biol Cell. 2005;97:235–252. doi: 10.1042/BC20040097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilusz CJ, Wormington M, Peltz SW. The cap-to-tail guide to mRNA turnover. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:237–246. doi: 10.1038/35067025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu K, Bogert BA, Li W, Su K, Lee A, Gao FB. The fragile X-related gene affects the crawling behavior of Drosophila larvae by regulating the mRNA level of the DEG/ENaC protein pick-pocket1. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1025–1034. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.05.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Jakymiw A, Wood MR, Eystathioy T, Rubin RL, Fritzler MJ, Chan EK. GW182 is critical for the stability of GW bodies expressed during the cell cycle and cell proliferation. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:5567–5578. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou C, Zhang Z, Wu S, Osterman JC. Molecular cloning and characterization of a rabbit eIF2C protein. Gene. 1998;211:187–194. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00107-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.