Abstract

Objective:

The purpose of this cross-sectional study was to determine the prevalence and potential significance of stroke symptoms among end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients without a prior diagnosis of stroke or TIA.

Methods:

We enrolled 148 participants with ESRD from 5 clinics. Stroke symptoms and functional status, basic and instrumental activities of daily living (ADL, IADL), were ascertained by validated questionnaires. Cognitive function was assessed with a neurocognitive battery. Cognitive impairment was defined as a score 2 SDs below norms for age and education in 2 domains. IADL impairment was defined as needing assistance in at least 1 of 7 IADLs.

Results:

Among the 126 participants without a prior stroke or TIA, 46 (36.5%) had experienced one or more stroke symptoms. After adjustment for age, sex, race, education, language, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease, participants with stroke symptoms had lower scores on tests of attention, psychomotor speed, and executive function, and more pronounced dependence in IADLs and ADLs (p ≤ 0.01 for all). After adjustment for age, sex, race, education, language, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease, participants with stroke symptoms had a higher likelihood of cognitive impairment (odds ratio [OR] 2.47, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.03–5.92) and IADL impairment (OR 3.86, 95% CI 1.60–9.28).

Conclusions:

Stroke symptoms are common among patients with ESRD and strongly associated with impairments in cognition and functional status. These findings suggest that clinically significant stroke events may go undiagnosed in this high-risk population.

Compared to the general population, the incidence of stroke is 6 to 10 times higher among patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) receiving maintenance dialysis.1 Despite frequent contact with health care professionals, patients with ESRD often present late after the onset of stroke symptoms and experience short-term mortality rates in excess of 35%, with very high rates of disability among survivors.2 Earlier recognition of stroke symptoms is essential in this high-risk population in order to reduce stroke-related morbidity and prevent future strokes.

Among patients with ESRD without a history of stroke, infarcts detected by MRI are present in up to 50%.3 In the general population, the presence of these so-called “silent” infarcts doubles the risk of subsequent stroke or dementia, highlighting the important long-term consequences of events presumed to be clinically silent.4 It is also possible that these events are not truly silent, but rather escape clinical detection. For example, in a large community cohort, a self-reported history of stroke symptoms was present in 18% of adults without a clinical history of stroke or TIA, and was associated with a higher prevalence of stroke risk factors and a higher prevalence of cognitive impairment.5,6 However, the prevalence and clinical significance of stroke symptoms in patients with ESRD is not well understood. Patients with ESRD often experience a large number of chronic symptoms that are often severe.7 They also have a high prevalence of conditions that may mimic stroke, such as peripheral neuropathies, retinopathy, hypoglycemia, and seizures. Certain vascular access complications can also mimic stroke symptoms. Thus transient neurologic symptoms suggestive of stroke may not reach the threshold required for clinical diagnosis or may be misdiagnosed as another condition.

The objective of the present study was to determine the prevalence of stroke symptoms and associated clinical correlates in an ambulatory cohort of patients with ESRD who lacked a clinical diagnosis of stroke or TIA. We also wished to determine the potential clinical significance of these symptoms by evaluating the association of stroke symptoms with cognitive function and functional status.

METHODS

Participants.

From March 2009 through October 2010, we recruited participants from 5 outpatient dialysis clinics in Northern California. Eligible participants were at least 21 years of age and receiving maintenance dialysis for at least 90 days. Participants were excluded if they were not fluent in English or Spanish, if they had an active psychiatric disorder including dementia, or if they had significant visual or hearing impairment. A total of 720 individuals were screened, and 477 were considered eligible for the study. We contacted 348 eligible individuals based on geographic proximity to our center, and 150 consented to participate in the study. Two participants were found to be ineligible and were subsequently withdrawn, resulting in a study sample of 148 participants. Eligible individuals who declined participation were older (63 ± 16 years vs 56 ± 15 years), less likely to be white (25% vs 43%), and received dialysis for a longer period of time compared to study participants (66 ± 41 months vs 40 ± 37 months).

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents.

The Committees on Human Research at Stanford University, Santa Clara Valley Medical Center, and the Palo Alto Veterans Affairs Health Care System approved the study and all participants provided informed consent.

Stroke symptoms.

Stroke or TIA was defined by self-report (“Were you ever told by a physician that you had a stroke?” and “Were you ever told by a physician that you had a TIA, mini-stroke, or TIA?”) or a recorded diagnosis in the dialysis chart. Experience of 6 different stroke symptoms was ascertained using the Questionnaire for Verifying Stroke Free Status (QVSFS) which assesses whether the respondent has ever experienced sudden onset of unilateral numbness, unilateral weakness, loss of ability to communicate, loss of ability to understand, loss of vision, and loss of half the visual field. The QVSFS is a validated questionnaire proposed as a screening instrument for identification of stroke-free individuals in a general population.8 A positive response to one or more symptoms on the QVSFS has been shown to be sensitive for detecting stroke and TIA as determined by neurologic interview and examination (sensitivity, 0.82–0.97), although specificity is only modest (specificity, 0.60–0.62).8,9 Presence of stroke symptoms was defined as answering yes to one or more symptoms.

Cognitive function and functional status.

We evaluated cognitive function with a neuropsychological battery assessing domains of global cognition, attention, psychomotor speed, executive function, verbal fluency, and verbal memory. Testing was conducted in a quiet room prior to a midweek dialysis session and administered by trained research staff. Global cognition was assessed with the Modified Mini-Mental State Examination (3MS). Attention was assessed with the Trail Making Test Part A (Trails A) and executive function with Part B (Trails B) as well as the Digit Symbol Substitution Test. Memory was assessed with the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT) immediate and delayed recall components, psychomotor speed in dominant and nondominant hands was assessed with the Grooved Pegboard Test, and verbal fluency was assessed among English-speaking participants only with the Controlled Oral Word Association Test (COWAT). Cognitive impairment was defined as a score at least 2 SD below normative values for age and education (where available) in 2 or more cognitive domains.10,11 If a test was not attempted, then the participant was classified as not impaired on this test. Functional status was measured by assessing the degree of assistance required in 7 instrumental activities of daily living (IADL)—telephone use, shopping for groceries, using transportation, meal preparation, housework, taking medications, and handling finances—and in 4 basic activities of daily living (ADL)—bathing, dressing, ambulating, and transferring from a chair.12,13 Each item on the 7-item IADL scale is rated from 0 to 2 and each item on the 4-item ADL scale ranges is rated from 0 to 3, with higher scores indicating higher functional status. IADL impairment was defined as needing assistance in any of the 7 IADLs, and ADL impairment was defined as needing assistance in any of the 4 ADLs.12

Covariates.

Participants completed a study questionnaire which assessed demographic, clinical, and psychosocial characteristics. Educational attainment was classified as less than high school graduate, high school graduate, or some college education. Diabetes was defined as self-report or chart history of diabetes or use of medications for diabetes. Hypertension was defined as self-report of hypertension or use of medications for hypertension. Cardiovascular disease was defined as coronary artery disease (self-report or chart history of a myocardial infarction, coronary angioplasty, or coronary stent placement) or peripheral arterial disease (self-report or chart history of lower extremity angioplasty or stent placement). Heart failure was defined as self-report or chart history. Depressive symptoms were defined as a score of 6 or more on the Geriatric Depression Scale short form.14 Laboratory results and use of erythropoiesis stimulating agents within 1 month of enrollment were abstracted from the dialysis chart. Blood pressure and weight were measured prior to the start of dialysis.

Statistical analysis.

The main analyses excluded participants with a diagnosis of prior stroke or TIA. We compared characteristics of those with no stroke symptoms to those with stroke symptoms using analysis of variance or the Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables and the χ2 test for categorical variables. We used linear regression to determine the association between the presence of stroke symptoms and scores on each cognitive test and functional status measure. In multivariable models, we adjusted for age, sex, race, education, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease (coronary or peripheral arterial disease). Next, we used logistic regression to determine the association, expressed as an odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) between stroke symptoms and cognitive impairment. We constructed 2 models: an unadjusted model and a parsimonious adjusted model that included age, sex, race, education, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. We then added additional covariates to the parsimonious model to determine whether their inclusion in the model changed the parameter estimate for stroke symptoms by more than 10%. We used a similar approach to model the association between stroke symptoms and IADL impairment. We were not able to construct adjusted models for the outcome of ADL impairment due to the low prevalence of this outcome. Analyses were performed using SAS v9.2 (www.sas.com).

RESULTS

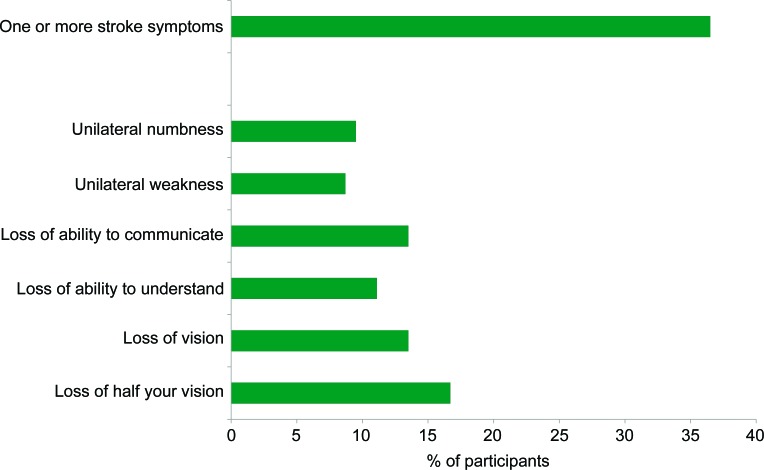

There were 22 participants with a prior diagnosis of stroke or TIA. Among the remaining 126 participants, there were 46 (36.5%) who reported one or more stroke symptoms (figure 1). Sudden unilateral weakness was the least commonly reported symptom (n = 11, 8.7%), and sudden loss of half the visual field was the most commonly reported symptom (n = 21, 16.7%). Sixteen participants (12.7%) experienced 1 symptom, 21 (16.7%) experienced 2 symptoms, and 9 (7%) experienced 3 or more stroke symptoms.

Figure 1. Prevalence and type of stroke symptoms among dialysis participants without a history of stroke or TIA.

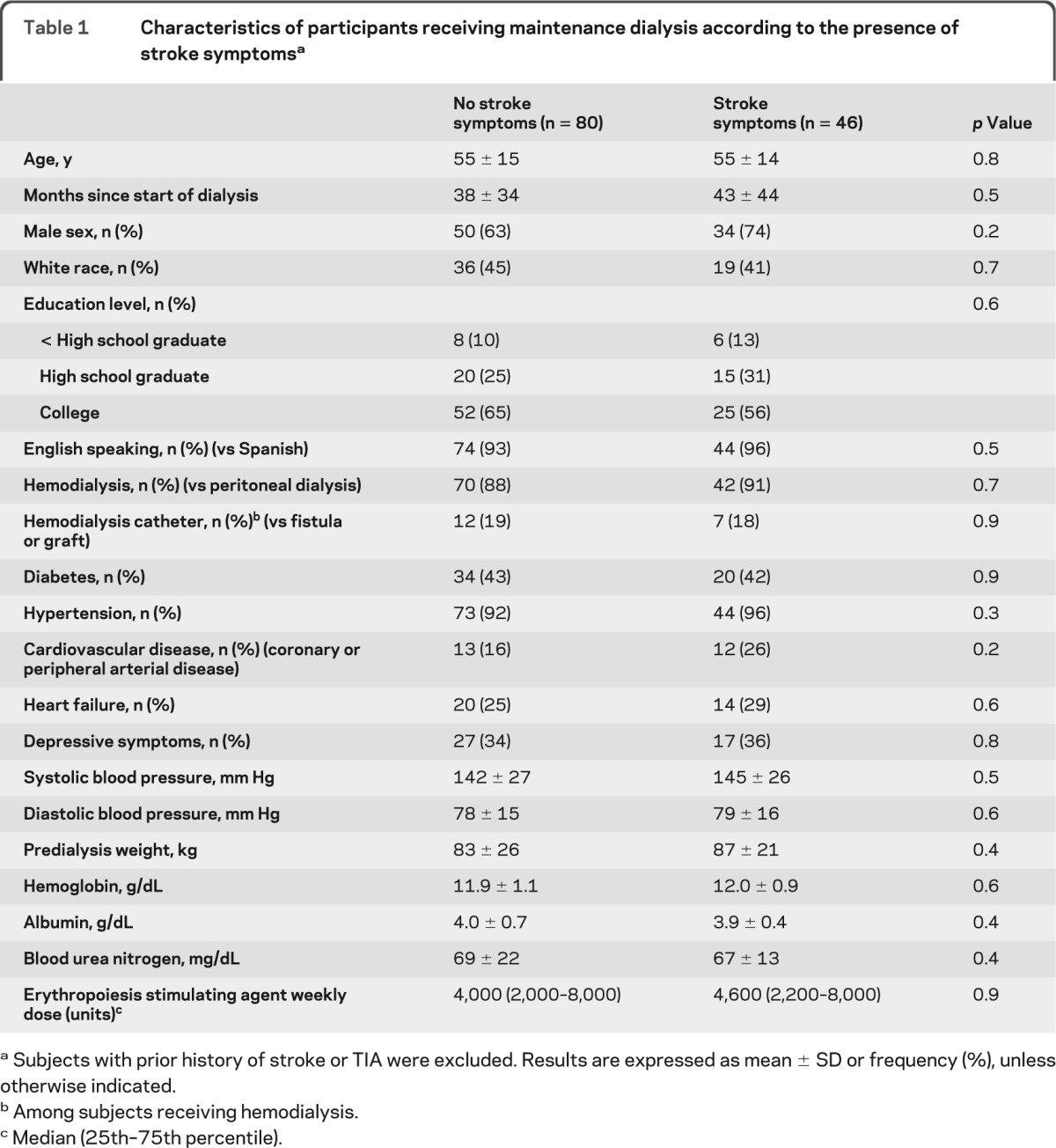

The clinical characteristics of participants with stroke symptoms were very similar to participants without stroke symptoms (table 1). As compared to participants without a prior diagnosis of stroke or TIA, participants with a prior diagnosis of stroke were more likely to be nonwhite and more likely to have cardiovascular disease (data not shown).

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants receiving maintenance dialysis according to the presence of stroke symptomsa

Subjects with prior history of stroke or TIA were excluded. Results are expressed as mean ± SD or frequency (%), unless otherwise indicated.

Among subjects receiving hemodialysis.

Median (25th–75th percentile).

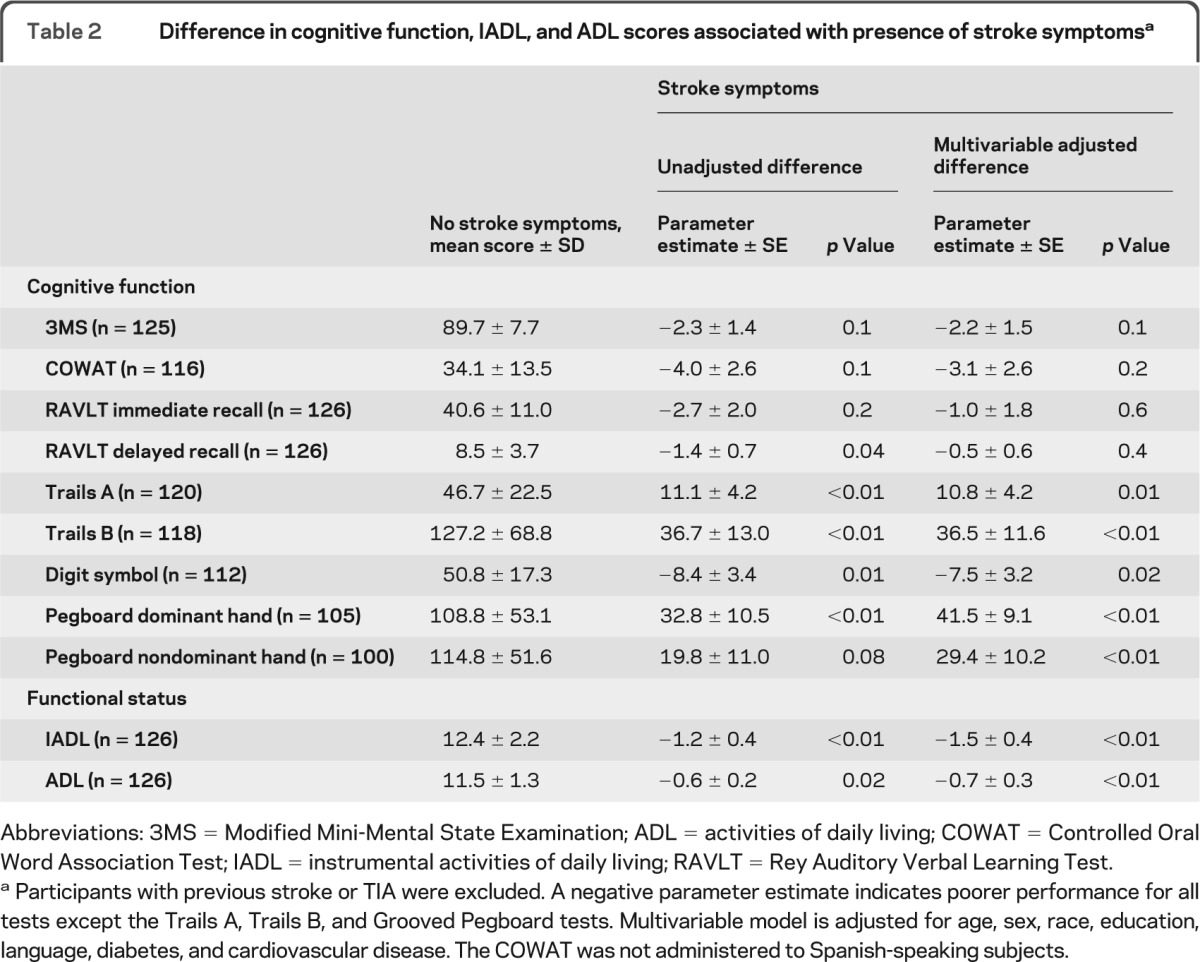

In unadjusted analyses, the presence of one or more stroke symptoms was associated with poorer cognitive function on 5 of the 9 cognitive function tests administered (table 2). After adjustment for demographics, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease, tests of global cognition, verbal fluency, and memory were not significantly associated with stroke symptoms. However, tests of attention, executive function, and psychomotor speed remained significantly associated with stroke symptoms. Similarly, the presence of one or more stroke symptoms was associated with poorer functional status, as indicated by lower scores on the IADL and ADL scales (table 2). These findings persisted after adjustment for demographics, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.

Table 2.

Difference in cognitive function, IADL, and ADL scores associated with presence of stroke symptomsa

Abbreviations: 3MS = Modified Mini-Mental State Examination; ADL = activities of daily living; COWAT = Controlled Oral Word Association Test; IADL = instrumental activities of daily living; RAVLT = Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test.

Participants with previous stroke or TIA were excluded. A negative parameter estimate indicates poorer performance for all tests except the Trails A, Trails B, and Grooved Pegboard tests. Multivariable model is adjusted for age, sex, race, education, language, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. The COWAT was not administered to Spanish-speaking subjects.

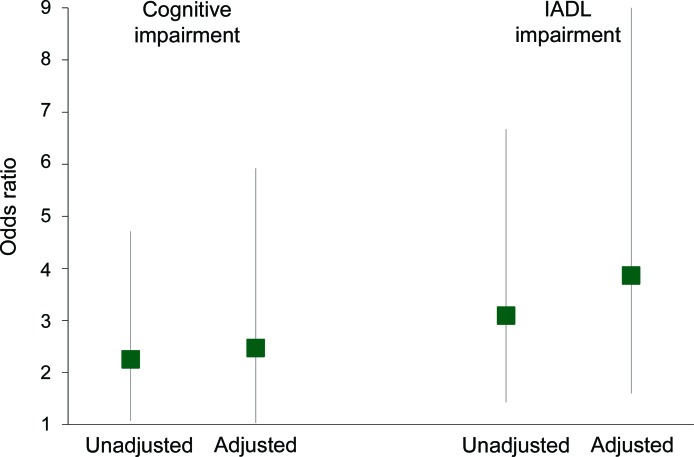

There were 58 participants (46.0%) who met the definition of cognitive impairment. In a parsimonious model adjusted for age, sex, race, education, language, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease, stroke symptoms were associated with a higher odds of cognitive impairment (OR 2.47, 95% CI 1.03–5.92) (figure 2). The inclusion of other comorbid conditions, depressive symptoms, blood pressure, or length of time on dialysis did not change this association. There were 66 participants (52.4%) who met the definition of IADL impairment. Stroke symptoms were associated with a 3-fold higher odds of IADL impairment (OR 3.86, 95% CI 1.60–9.28) after adjustment for age, sex, race, education, language, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease (figure 2). Additional adjustment for cognitive impairment did not change the findings (OR 3.47, 95% CI 1.43–8.42), nor did the inclusion of other comorbid conditions, depressive symptoms, blood pressure, or length of time on dialysis. There were 14 participants (11.1%) who met the definition of ADL impairment. Participants with stroke symptoms were more likely to have ADL impairment compared to participants without stroke symptoms (19.6% vs 6.3%, p = 0.02).

Figure 2. Association of stroke symptoms with cognitive impairment and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) impairment among dialysis participants.

The multivariable models are adjusted for age, sex, race, education, language, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Cognitive impairment adjusted model c = 0.75. IADL impairment adjusted model c = 0.69.

DISCUSSION

We found one-third of ESRD patients without a previously diagnosed stroke or TIA had experienced stroke symptoms. The presence of stroke symptoms was associated with a 2- to 3-fold higher odds of cognitive impairment, IADL impairment, and ADL impairment, independent of age, race, and other confounding factors. These findings suggest that clinically significant stroke events may go undiagnosed in this high-risk population.

The incidence of stroke is 6 to 10 times higher among patients with ESRD compared to the general population. Furthermore, patients with ESRD who have a stroke have high case-fatality rates and low rates of recovery. These poor outcomes may stem from late recognition of stroke symptoms. In a prospective study of 1,041 new dialysis patients, stroke occurred in 10% of the patients.2 Patients ultimately diagnosed with stroke presented a median of 8.5 hours after the onset of symptoms. The delay in recognition of stroke symptoms is particularly concerning given that the majority of dialysis patients have regular contact with medical professionals during their dialysis treatments. Our findings suggest that many patients with ESRD experience stroke symptoms that escape clinical detection. This may be because the symptoms are transient, or because they are misdiagnosed as another condition.

These results are consistent with recent reports from the REasons for Geographic And Racial Disparities in Stroke (REGARDS) study. In REGARDS, which also ascertained stroke symptoms using the QVSFS, stroke symptoms were present in 18% of community-dwelling adults with no prior history of stroke or TIA.15 In REGARDS, the incidence of stroke symptoms was higher among participants with chronic kidney disease (CKD) compared to participants with normal kidney function.16 Using a different methodology to ascertain stroke symptoms, the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study reported a stroke symptom prevalence of 13% among middle-aged adults.17 The prevalence of stroke symptoms observed in our study was 2- to 3-fold higher than that observed in REGARDS and ARIC. In addition, the prevalence of stroke or TIA in our cohort was 15%, comparable to the prevalence of stroke or TIA in 2 large ESRD cohorts,2,18 which would suggest that our results are not attributable to low ascertainment of previously diagnosed stroke.

In support of the idea that stroke symptoms represent undiagnosed strokes, we found that the odds of cognitive impairment, IADL impairment, and ADL impairment were 2 to 3 times higher in participants with stroke symptoms, independent of age and other factors. Furthermore, stroke symptoms were independently associated with impairment in attention, psychomotor speed, and executive function, cognitive domains strongly linked with small vessel cerebrovascular disease, but not with verbal fluency and verbal memory domains, which are often impaired in neurodegenerative diseases.

There is a high prevalence of cognitive impairment and disability in the ESRD population,10,19 and cerebrovascular disease is a recognized risk factor for these outcomes. However, our findings suggest that the extent to which cerebrovascular disease contributes to cognitive and functional impairment has been underappreciated. We did not perform neuroimaging in the current study; thus we were unable to determine whether neuroimaging markers of cerebrovascular disease correlated with stroke symptoms or with impairments in cognition and functional status. It is possible that these associations are not causal, but rather reflect confounding from illness severity. However, the magnitude of these associations, particularly for domains linked with vascular causes of cognitive impairment, and the absence of attenuation even after adjustment for several comorbid conditions would suggest that differences in underlying illness severity are not likely to fully explain the findings.

The reasons for elevated stroke risk among patients with ESRD are not fully understood. Patients with ESRD have a high prevalence of several traditional stroke risk factors, such as older age, black race, diabetes, and hypertension. Conversely, other traditional stroke risk factors, such as hyperlipidemia or atrial fibrillation, are not consistently associated with stroke risk in patients with ESRD.20 Factors related to ESRD or dialysis therapy are speculated to contribute to stroke risk. For example, in 2 large studies of patients with ESRD, stroke risk and stroke mortality were associated with markers of malnutrition such as low serum albumin and low body weight.18,21 Acute effects of the hemodialysis procedure, such as reductions in cerebral blood flow, have been suggested to correlate with stroke in some studies.22,23 Medications administered during hemodialysis, such as anticoagulants or erythropoiesis stimulating agents, may also contribute to stroke risk in patients with ESRD.24,25 With the exception of nonwhite race and preexisting cardiovascular disease, we did not find differences in clinical characteristics among ESRD participants with vs without prior stroke or TIA, or among ESRD participants with vs without stroke symptoms.

Patients with ESRD also have a high burden of small vessel cerebrovascular disease in the absence of diagnosed stroke. For example, in a sample of 123 hemodialysis patients without prior stroke or TIA, silent infarcts were present in almost 50% of the sample, a 5-fold higher prevalence compared to healthy control subjects.3 In the same cohort, silent infarcts were associated with a 7-fold higher risk for future stroke or cardiovascular events.26 Similar findings have been noted among persons with CKD not on dialysis.27,28 Given the costs of neuroimaging, prospective studies using the QVSFS or similar questionnaires may be an informative and efficient way to study stroke risk factors in this population.

There are several strengths of our study, including the racially diverse sample, ascertainment of stroke symptoms using a validated questionnaire, and the use of a neurocognitive battery to evaluate cognitive function. There are also several limitations. Our sample was drawn from a single geographic site and may not be generalizable to the larger ESRD population. We lacked neuroimaging, so we could not determine the sensitivity or specificity of stroke symptoms identified in our study. In particular, it is possible the specificity of the QVSFS is lower among patients with ESRD. We were unable to assess whether patients who reported stroke symptoms underwent any diagnostic investigations and what the outcomes of these investigations were. We relied on self-report to ascertain stroke symptoms and self-report or chart diagnosis to ascertain other comorbid conditions. These methods may be subject to ascertainment and recall bias related to cognitive impairment or poor health literacy. Because this is a cross-sectional study, we could not determine whether stroke symptoms were causally related to cognitive impairment and ADL or IADL impairment. Finally, it should be noted that the odds ratios reported here should not be interpreted as relative risks, since odds ratios overestimate the relative risk when the outcome is common.

Stroke symptoms were common among patients with ESRD without a previously diagnosed stroke or TIA, and were associated with a 2- to 3-fold higher odds of cognitive impairment and functional status impairment. Efforts to increase awareness and screening for stroke symptoms, especially among dialysis providers and patients, would seem warranted in order to reduce stroke-related morbidity and prevent future strokes.

Supplementary Material

GLOSSARY

- 3MS

Modified Mini-Mental State Examination

- ADL

activities of daily living

- ARIC

Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities

- CI

confidence interval

- CKD

chronic kidney disease

- COWAT

Controlled Oral Word Association Test

- ESRD

end-stage renal disease

- IADL

instrumental activities of daily living

- OR

odds ratio

- QVSFS

Questionnaire for Verifying Stroke Free Status

- RAVLT

Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test

- REGARDS

REasons for Geographic And Racial Disparities in Stroke

Footnotes

Editorial, page 960

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Dr. Kurella Tamura designed the study, obtained funding, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. Ms. Biada Meyer acquired the data, supervised the study, and contributed to interpretation of the data and revision of the manuscript content. Dr. Saxena contributed to coordination of the study and interpretation of the data and revision of the manuscript content. Dr. Huh contributed to interpretation of the data and revision of the manuscript content. Dr. Wadley contributed to interpretation of the data and revision of the manuscript content. Dr. Schiller contributed to coordination of the study and interpretation of the data and revision of the manuscript content.

DISCLOSURE

M. Kurella Tamura receives grant support from NIH and has served on a Scientific Advisory Board for Amgen. J. Biada Meyer reports no disclosures. A. Saxena has received honoraria from Wake Forest University. J.W.T. Huh reports no disclosures. V. Wadley receives grant support from Genzyme Therapeutics and NIH and has served on a Scientific Advisory Board for Amgen. B. Schiller is Chief Medical Officer of Satellite Healthcare, serves on the Scientific Advisory Boards for Affymax and NxStage, and as a Consultant to Takeda. Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1. Seliger SL, Gillen DL, Longstreth WT, Jr, Kestenbaum B, Stehman-Breen CO. Elevated risk of stroke among patients with end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int 2003; 64: 603– 609 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sozio SM, Armstrong PA, Coresh J, et al. Cerebrovascular disease incidence, characteristics, and outcomes in patients initiating dialysis: the Choices for Healthy Outcomes in Caring for ESRD (CHOICE) study. Am J Kidney Dis 2009; 54: 468– 477 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nakatani T, Naganuma T, Uchida J, et al. Silent cerebral infarction in hemodialysis patients. Am J Nephrol 2003; 23: 86– 90 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vermeer SE, Prins ND, den Heijer T, Hofman A, Koudstaal PJ, Breteler MM. Silent brain infarcts and the risk of dementia and cognitive decline. N Engl J Med 2003; 348: 1215– 1222 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wadley VG, McClure LA, Howard VJ, et al. Cognitive status, stroke symptom reports, and modifiable risk factors among individuals with no diagnosis of stroke or transient ischemic attack in the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study. Stroke 2007; 38: 1143– 1147 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Howard VJ, McClure LA, Meschia JF, Pulley L, Orr SC, Friday GH. High prevalence of stroke symptoms among persons without a diagnosis of stroke or transient ischemic attack in a general population: the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study. Arch Intern Med 2006; 166: 1952– 1958 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Weisbord SD, Fried LF, Arnold RM, et al. Prevalence, severity, and importance of physical and emotional symptoms in chronic hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 2005; 16: 2487– 2494 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jones WJ, Williams LS, Meschia JF. Validating the Questionnaire for Verifying Stroke-free Status (QVSFS) by neurological history and examination. Stroke 2001; 32: 2232– 2236 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sung VW, Johnson N, Granstaff US, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of stroke symptom questions to detect stroke or transient ischemic attack. Neuroepidemiology 2011; 36: 100– 104 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Murray AM, Tupper DE, Knopman DS, et al. Cognitive impairment in hemodialysis patients is common. Neurology 2006; 67: 216– 223 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Plassman BL, Langa KM, Fisher GG, et al. Prevalence of cognitive impairment without dementia in the United States. Ann Intern Med 2008; 148: 427– 434 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gill TM, Hardy SE, Williams CS. Underestimation of disability in community-living older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002; 50: 1492– 1497 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist 1969; 9: 179– 186 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lesher EL, Berryhill JS. Validation of the geriatric depression scale–short form among inpatients. J Clin Psychol 1994; 50: 256– 260 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Howard G, Safford MM, Meschia JF, et al. Stroke symptoms in individuals reporting no prior stroke or transient ischemic attack are associated with a decrease in indices of mental and physical functioning. Stroke 2007; 38: 2446– 2452 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Muntner P, Judd SE, McClellan W, Meschia JF, Warnock DG, Howard VJ. Incidence of stroke symptoms among adults with chronic kidney disease: Results from the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012; 27: 166– 173 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Toole JF, Lefkowitz DS, Chambless LE, Wijnberg L, Paton CC, Heiss G. Self-reported transient ischemic attack and stroke symptoms: methods and baseline prevalence: the ARIC Study, 1987–1989. 1996; Am J Epidemiol 144: 849– 856 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Delmez JA, Yan G, Bailey J, et al. Cerebrovascular disease in maintenance hemodialysis patients: Results of the HEMO study. Am J Kidney Dis 2006; 47: 131– 138 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cook WL, Jassal SV. Functional dependencies among the elderly on hemodialysis. Kidney Int 2008; 73: 1289– 1295 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Genovesi S, Vincenti A, Rossi E, et al. Atrial fibrillation and morbidity and mortality in a cohort of long-term hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 2008; 51: 255– 262 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Seliger SL, Gillen DL, Tirschwell D, Wasse H, Kestenbaum BR, Stehman-Breen CO. Risk factors for incident stroke among patients with end-stage renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2003; 14: 2623– 2631 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Toyoda K, Fujii K, Fujimi S, et al. Stroke in patients on maintenance hemodialysis: a 22-year single-center study. Am J Kidney Dis 2005; 45: 1058– 1066 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stefanidis I, Bach R, Mertens PR, et al. Influence of hemodialysis on the mean blood flow velocity in the middle cerebral artery. Clin Nephrol 2005; 64: 129– 137 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pfeffer MA, Burdmann EA, Chen CY, et al. A trial of darbepoetin alfa in type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 2009; 361: 2019– 2032 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Seliger SL, Zhang AD, Weir MR, et al. Erythropoiesis-stimulating agents increase the risk of acute stroke in patients with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2011; 80: 288– 294 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Naganuma T, Uchida J, Tsuchida K, et al. Silent cerebral infarction predicts vascular events in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int 2005; 67: 2434– 2439 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Khatri M, Wright CB, Nickolas TL, et al. Chronic kidney disease is associated with white matter hyperintensity volume: The Northern Manhattan Study (NOMAS). Stroke 2007; 38: 3121– 3126 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ikram MA, Vernooij MW, Hofman A, Niessen WJ, van der Lugt A, Breteler MM. Kidney function is related to cerebral small vessel disease. Stroke 2008; 39: 55– 61 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.