Abstract

The embryonic – abembryonic (Em–Ab) axis of the mouse blastocyst has been found in several studies to align orthogonal to the first cleavage plane, raising the possibility that a developmental prepattern already exists at the two-cell stage. However, it is also possible that such alignment is not due to any developmental disparity between the two-cell stage blastomeres, but rather is caused by an extrinsic mechanical constraint that is conferred by an irregular shape of the zona pellucida (ZP). Here, we conducted a series of experiments to distinguish between these possibilities. We showed that the shape of the ZP at the two-cell stage varied among embryos, ranging from near spherical to ellipsoidal, and that the ZP shape did not change until the blastocyst stage. In those embryos with an ellipsoidal ZP, the Em–Ab axis tended to lie orthogonal to the first cleavage plane, while in those embryos with a near spherical ZP, there was no such relationship. The clonal boundary between the descendants of the two-cell stage blastomeres tended to lie orthogonal to the Em–Ab axis when the rotation of the embryo within the ZP was experimentally prevented, while the control embryos did not exhibit such tendency. These results support the possibility that an apparent correlation between the first cleavage plane and the blastocyst axis can be generated by the mechanical constraint from the ZP but not by a developmental prepattern. Moreover, recent reports indicate that the vegetal blastomere of the four-cell stage embryo that had undergone a specific type of second cleavages is destined to contribute to the abembryonic side of the blastocyst. However, our present study shows that in spite of such specific second cleavages, the vegetal blastomere did not preferentially give rise to the abembryonic side. This result implicates that the lineage of the four-cell stage blastomere is not restricted even when embryos undergo a specific type of second cleavages.

Keywords: embryonic–abembryonic axis, prepattern, cell lineage, zona pellucida, alginate gel, time-lapse videomicroscopy

INTRODUCTION

The first critical event for mouse embryo development is the formation of the blastocyst. The blastocyst is composed of two types of morphologically and functionally distinct cells: inner cell mass (ICM) and trophectoderm (TE). TE forms an epithelial layer, surrounding the blastocyst cavity, while ICM, as an aggregate of cells, is asymmetrically located in the blastocyst cavity by attaching to the inner surface of TE (Fig. 1A). The association with ICM is critical for the further differentiation of TE, as the signals from ICM induce the adjacent TE, called polar TE, to give rise to the extraembryonic ectoderm, which is the precursor of the trophoblast of the placenta. A population of ICM cells differentiates into the primitive endoderm on the side facing the blastocyst cavity, while the remaining ICM cells give rise to the epiblast, which is the sole precursor of all the fetal tissues. Thus, the asymmetric localization of ICM within the blastocyst cavity sets the embryonic–abembryonic (Em–Ab) axis, which corresponds to the proximal–distal axis of the egg cylinder embryo after implantation (reviewed in Beddington and Robertson, 1999; Tam et al., 2006; Yamanaka et al., 2006).

Fig. 1.

A: A blastocyst develops within the zona pellucida (ZP), and is composed of two distinct cell populations, that is, inner cell mass (ICM) and trophectoderm (TE). The embryonic–abembryonic axis of the blastocyst is defined based on the location of ICM relative to the blastocyst cavity. B: A schematic diagram depicting how the mechanical constraint model can explain some of the observations which the prepattern model is based on (see text for details). C: The orientations of the second cleavages are categorized into meridional (M) and equatorial (E) with respect to the animal–vegetal axis (see text for details).

The fundamental question is whether the Em–Ab axis, that is, the asymmetric localization of ICM within the blastocyst cavity, is specified by a pattern that may exist in the preceding developmental stages, or is merely a result of random attachment of ICM to TE. The former scenario is referred to as “the prepattern model,” and has been the focus of intensive studies in the past several years (reviewed in Hiiragi et al., 2006; Zernicka-Goetz, 2006). The reports from several groups (Gardner, 2001; Piotrowska et al., 2001; Fujimori et al., 2003) indicate that the plane of the first cleavage (i.e., boundary between the two-cell stage blastomeres) tends to align orthogonal to the Em–Ab axis of the early blastocyst. An implication of these observations is that one blastomere in the two-cell stage embryo contributes mainly to the embryonic half and the other blastomere to the abembryonic half of the blastocyst. By contrast, this prepattern model is contradictory to the reports from several other groups (Alarcón and Marikawa, 2003; Chroscicka et al., 2004; Motosugi et al., 2005), as they observed no significant correlation between the lineages of the two-cell stage blastomeres and the Em–Ab axis of the early blastocyst.

To resolve such discrepancy, “the mechanical constraint model” (Fig. 1B) has been proposed (Alarcón and Marikawa, 2003; Motosugi et al., 2005). In this model, the zona pellucida (ZP), particularly when its shape is ellipsoidal, imposes physical restriction on the orientation of the two-cell stage embryo and on the position of the blastocyst cavity at the early blastocyst stage. Namely, the two blastomeres of the two-cell stage embryo are likely to line up along the longest diameter of the ZP, and the blastocyst cavity is more stably situated at one end of the long axis of the embryo. As a result, the first cleavage plane tends to align orthogonal to the Em–Ab axis of the early blastocyst. If physical constraints upon the embryo lead to preferential orientation of embryos at the two-cell and blastocyst stages, the descendants of the two blastomeres “appear” to segregate between the embryonic and abembryonic halves (Fig. 1B). Thus, the mechanical constraint model is consistent with the observations that the prepattern model is based on (Gardner, 2001; Piotrowska et al., 2001; Fujimori et al., 2003), and also with the studies showing that the developmental lineages of the two-cell stage blastomeres have no relationship with the Em–Ab axis (Alarcón and Marikawa, 2003; Chroscicka et al., 2004; Motosugi et al., 2005).

The mechanical constraint model, however, has also been criticized (Gardner, 2005, 2006, 2007). In some cases, even when the shapes of embryos are significantly constricted, the alignment of the Em–Ab axis across the first cleavage plane is not as prominent as in less constricted embryos. This was pointed out as the examples against the mechanical constraint model (Gardner, 2001, 2005). In another study (Gardner, 2007), the sites of the ZP that pass along the first cleavage plane were marked with oil droplets at the two-cell stage. When the embryos reached the morula stage, a cell near the oil marks was labeled with a fluorescent dye. The descendants of the labeled cell tended to be found at the blastocyst stage near the boundary between the embryonic and abembryonic halves, supporting the orthogonal relationship between the first cleavage plane and the Em–Ab axis. Importantly, the tendency of the labeled cell to contribute to the equatorial region of the blastocyst was also observed even when the ZP was softened or removed after labeling. This implicates that the mechanical constraint from the overlying ZP was not necessary for the blastocyst cavity to form at the location orthogonal to the first cleavage plane (Gardner, 2007). In addition, it has been suggested that the contradictory observations among investigators on the lineages of the two-cell stage blastomeres may be due to differences in the mouse strains, differences in the quality of embryos, or possible inaccuracy of the observation methods (discussed in Rossant and Tam, 2004; Zernicka-Goetz, 2004; Gardner, 2005, 2006; Hiiragi et al., 2006), although none of these have been demonstrated to be the cause of the contradictions. In the present study, to evaluate the validity of the mechanical constraint model, we conducted several experiments, which involve the measurement of the ZP shape, the time-lapse recording of developing embryos, and the lineage tracing of two-cell stage blastomeres that are embedded in alginate gel. While this study was on-going, a report was published that also addressed the validity of the mechanical constraint model with similar experimental approaches (Kurotaki et al., 2007). As described in Discussion Section, our results are totally consistent with those of Kurotaki et al. (2007). Such consistency and reproducibility of experimental data among different research groups are particularly vital in light of the current controversy in the field.

Also, in the present study, we examined the applicability of the scenario that was recently proposed by a research group as an elaboration of the prepattern model (Piotrowska-Nitsche and Zernicka-Goetz, 2005; Piotrowska-Nitsche et al., 2005; Torres-Padilla et al., 2007). In this particular scenario, a blastomere in the four-cell stage embryo that has undergone a specific pattern of second cleavages almost exclusively contributes to the mural TE, a group of TE that is located in the abembryonic half of the blastocyst. Typically, the second cleavages, that is, the cell divisions from the two-cell to four-cell stages, are asynchronous between the two blastomeres. Also, the orientation of the second cleavages may occur in two different ways. One is meridional, which runs parallel to the animal–vegetal axis, and the other is equatorial, which runs perpendicular to the animal–vegetal axis (Fig. 1C). When the earlier second cleavage is meridional and the later second cleavage is equatorial, the blastomere that is located at the vegetal side in the resulting four-cell stage embryo is most likely to contribute to the mural TE (Piotrowska-Nitsche et al., 2005). While other groups showed that the temporal order of the second cleavages had no significant correlation with the Em–Ab axis of the early blastocyst (Gardner, 2001; Fujimori et al., 2003; Alarcón and Marikawa, 2005; Motosugi et al., 2005; Waksmundzka et al., 2006), the orientation of the second cleavages was not investigated in those studies. Thus, to assess the validity of the above scenario, it is essential to examine both the timing and orientation of the second cleavages with respect to the Em–Ab axis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and Embryos

F1 (C57BL/6 × CBA), F1 (C57BL/6 × DBA/2) and CD-1 female mice (National Cancer Institute, Frederick, MD; Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) were superovulated by intraperitoneal injections of pregnant mare serum gonadotropin and human chorionic gonadotropin (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA), and mated with F1 (C57BL/6 × DBA/2) or CD-1 males. Animals were maintained according to the guidelines of the Laboratory Animal Services at the University of Hawaii and by the Committee for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Research Council (Committee to Revise the Guide, Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources Council, Commission on Life Sciences, National Research Council, 1996). The protocol of animal handling and treatment was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Two-cell stage embryos were flushed from the oviducts with FHMPVA medium (Alarcón and Marikawa, 2003) or EmbryoMax FHM HEPES Buffered Medium (Millipore, Billerica, MA), and were cultured in mKSOMAA medium (Alarcón and Marikawa, 2003) or EmbryoMax KSOM with Amino Acids, Glucose and Phenol Red (Millipore) under mineral oil at 37°C in 5% CO2 humidified air. To measure the diameters of the ZP at the two-cell stage, each embryo was held with a holding pipet and reoriented relative to the positions of the first cleavage plane and the second polar body, using a glass needle that was attached to a Model MWO-202 micromanipulator (Narishige, Tokyo, Japan) and Axiovert200 inverted microscope (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY).

Time-Lapse Videomicroscopy

For time-lapse recording of early development from the two-cell to the early blastocyst stages, up to 20 embryos were cultured in a 20 µL drop of the culture medium on a poly-d-lysine-coated coverslip (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA), which was placed in a Petri dish and covered with mineral oil. The Petri dish was placed in Heating Insert P (PeCon, Erbach, Germany), whose temperature and CO2 concentration were regulated by Tempcontrol 37-2 and CO2-Controller (PeCon), respectively. The Heating Insert P was enclosed in Incubator XL-3 (PeCon), attached to the inverted microscope with Hoffman Modulation Contrast optics. When plated dispersedly on a culture dish, most of the two-cell stage embryos tended to settle in such a way that the two blastomeres aligned parallel to the bottom of the dish. If not, a glass needle attached to the micromanipulator was used to reorient embryos. Images were captured every 20 min using AxioCam MRm, controlled by the AxioVision software (Carl Zeiss).

Cell Lineage Analysis and Filling the Perivitelline Space With Alginate Gel

The lipophilic, fluorescent dye DiI (1,1′-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) was used to label the plasma membrane of a blastomere, as previously described (Alarcón and Marikawa, 2003). Embryo rotation within the ZP was prevented by filling the perivitelline space with alginate gel (Gardner, 2004). DiI-labeled, two-cell stage embryos were incubated in mKSOMAA, containing 0.5% [w/v] sodium alginate (low viscosity; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 60 min at 37°C in 5% CO2 humidified air. The embryos were then briefly rinsed by serial transfers in drops of FHMPVA and were placed for 15 min in FHMPVA containing 10 mM CaCl2 to induce the solidification of alginate. Embryos were washed several times in FHMPVA, and cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2 humidified air until they reached the early blastocyst stage. Solidification of alginate after the CaCl2 treatment was confirmed by digesting the ZP of several embryos in 0.5% Pronase in FHMPVA and observing an encapsulation around the embryos.

RESULTS

The Ellipsoidal Shape of the ZP Persists Throughout Early Development

The mechanical constraint model is based on the presumption that the ellipsoidal shape of the ZP persists throughout early development to influence the orientations of the two-cell stage embryo and the Em–Ab axis of the early blastocyst (Alarcón and Marikawa, 2003; Motosugi et al., 2005). To assess whether this is the case, we measured the internal diameters of the ZP with respect to the orientation of the two-cell stage embryos, and monitored the shape of the ZP during early development by time-lapse videomicroscopy. For each two-cell stage embryo, the diameters of the ZP were measured in three different directions relative to the first cleavage plane and the location of the second polar body. The first diameter passes through the centers of both blastomeres and is perpendicular to the first cleavage plane, the second diameter is parallel to the first cleavage plane and passes through the polar body, and the third diameter is perpendicular to the first and second diameters (Fig. 2A). The lengths of the second and third diameters were normalized by that of the first diameter for each embryo, and the mean ± standard deviation of these values and their ranges are plotted on the graph (Fig. 2B). On average (n = 46), the second and third diameters, that is, those that are parallel to the first cleavage plane, were shorter than the first diameter, indicating that the shape of the ZP tended to be ellipsoidal. However, it is important to note that the extent of the ellipsoidal ZP shape varied significantly among embryos. In some embryos, the third diameter was shorter than the first diameter by over 15% (Fig. 2B). By contrast, the ZP of some other embryos was almost spherical, such that the differences among the three diameters were smaller than 5% (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Persistence of the ellipsoidal ZP shape throughout early development. A: The internal diameters of ZP are measured in three ways relative to the first cleavage plane and the position of the second polar body, as depicted in the figures. B: Mean, standard deviation (SD), and range of the ratios between the internal diameters of the ZP in the embryos examined (n = 46). C: Examples of embryos that were monitored by time-lapse videomicroscopy (n = 50). Images at the two-cell, four-cell, eight-cell, and morula stages are shown. The inner surface of the ZP for each embryo is highlighted with a white broken line. Note that the shape of the ZP persists regardless of the developmental stages of the embryos.

We then observed the shape of the ZP in time-lapse recordings from the two-cell to the blastocyst stage. The culture condition on the microscope stage was optimized so that the efficiency of embryo development, based on the timings of cell divisions, compaction, and blastocyst cavity formation, was indistinguishable from that of the control embryos in a conventional culture incubator. None of the embryos (n = 50) that we examined displayed a detectable change in the shape of the ZP from the two-cell to early blastocyst stage (Fig. 2C). After the blastocyst cavity significantly expanded and the perivitelline space disappeared, the ZP was stretched out by the embryo. Thus, the shape of the ZP, whether ellipsoidal or spherical, persisted throughout early development.

The Em–Ab Axis of the Early Blastocyst Lies More Orthogonal to the First Cleavage Plane When the Shape of the ZP Is More Ellipsoidal

The mechanical constraint model predicts that the Em–Ab axis of the early blastocyst would lie orthogonally to the first cleavage plane only when the persistent shape of the ZP is significantly ellipsoidal. Conversely, when the shape of the ZP is close to spherical, there would be no mechanical constraint to influence the position of the blastocyst cavity, and the Em–Ab axis would be positioned randomly relative to the first cleavage plane. To test whether this is the case, we analyzed by time-lapse videomicroscopy the relationships among the first cleavage plane, the shape of ZP, and the Em–Ab axis at the early blastocyst stage.

For this analysis, the shape of the ZP was measured as the ratio between the two internal diameters, that is, one passing through the first cleavage plane and the other running through the centers of both blastomeres (Fig. 3A–D). When an embryo reached the early blastocyst stage, we drew a line that was parallel to the floor of the blastocyst cavity, and then measured the angle between the line along the cavity floor and the first cleavage plane (Fig. 3B–D’). The angle and the shape of ZP for individual embryos were plotted on the graph (Fig. 3E, Table 1). When the ratio between the two ZP diameters was smaller than 0.95 (i.e., the circumference of ZP on the horizontal plane was more ellipsoidal), those embryos (n = 25) tended to exhibit the orthogonal relationship of the Em–Ab axis to the first cleavage plane. Specifically, the angle between the cavity floor and the first cleavage plane was between 0° and 30° in 60% of the embryos (15/25), between 31° and 60° in 36% of the embryos (9/25), and between 61° and 90° in 4% of the embryos (1/25). This is significantly different from what is expected when embryos are randomly assigned to the three angle categories (Chi-square test, P < 0.005). By contrast, when the ratio between the two ZP diameters was larger than 0.95 (i.e., the circumference of ZP was closer to circular), the angular relationship between the Em–Ab axis and the first cleavage plane varied markedly with no apparent bias in those embryos (n = 16; P > 0.9). These results are consistent with the prediction from the mechanical constraint model that is described above.

Fig. 3.

Relationship among the ZP shape, the first cleavage plane, and the Em–Ab axis. A: The shape of ZP is evaluated at the two-cell stage based on the ratio between the two internal diameters: one (a) is perpendicular to and the other (b) passes through the first cleavage plane. B: The angle (θ) between the first cleavage plane and the blastocyst cavity floor is measured at the early blastocyst stage. C,C’,D,D’: Two embryos are shown as examples of those (n = 41) that were monitored by time-lapse videomicroscopy. E: A scatter plot of the ZP shape (b/a) and the angle (θ). The data are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Relationship Among the ZP Shape, First Cleavage Plane, and Em–Ab Axis

| Number of embryos with a given angle (θ)b |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| ZP diameter ratio (b/a)a | 0°–30° | 31°–60° | 61°–90° |

| <0.95 | 15 | 9 | 1 |

| ≥0.95 | 6 | 5 | 5 |

The ratio between two internal diameters of the ZP at the two-cell stage, as described in the text and Figure 3A.

The definition of θ is described in the text and Figure 3B. A total of 56 embryos were monitored by time-lapse video-microscopy. Fifteen embryos were excluded from the analysis because they either moved away from the original position during time-lapse recording (6/15), or the blastocyst cavity floor could not be outlined due to its irregular shape (9/15).

Prevention of Embryo Rotation Within the ZP Increases the Incidence of Lineage Segregation Between the Embryonic and Abembryonic Halves

While the Em–Ab axis tended to lie orthogonally to the first cleavage plane in the embryos with an ellipsoidal ZP (Fig. 3E), several studies showed that the clonal boundary between the two-cell stage blastomeres did not correlate with the Em–Ab axis (Alarcón and Marikawa, 2003; Chroscicka et al., 2004; Motosugi et al., 2005). The mechanical constraint model predicts that the clonal boundary would align with the first cleavage plane only when the embryo does not significantly rotate within an ellipsoidal ZP (Fig. 1B; discussed in Hiiragi et al., 2006). To test whether this is the case, we prevented the rotation of the embryo in the ZP by filling the perivitelline space with alginate gel, and examined the distribution of the clonal descendants of the two-cell stage blastomeres with respect to the Em–Ab axis using the cell lineage tracer DiI.

After one blastomere was labeled with DiI at the two-cell stage, the embryos were separated into two groups. One group of embryos was incubated in the culture medium containing alginate for 60 min to equilibrate the perivitelline space with it (Fig. 4A). After several rinses in regular culture medium, the embryos were briefly exposed to the culture medium containing high concentration of calcium ion to solidify the alginate in the perivitelline space. The other group of embryos, as a control, was incubated in the culture medium without alginate, rinsed, and exposed to the high calcium medium. These treatments did not significantly impair the efficiency of development, regarding the timings of cell divisions, compaction, and blastocyst cavity formation. When the embryos reached the early blastocyst stage, the clonal boundary between the labeled and nonlabeled cells was assessed, particularly with regards to its angular relationship with the plane that was parallel to the blastocyst cavity floor (Fig. 4A,B). The control group embryos (n = 44) exhibited no significant bias (Chi-square test, P > 0.15) on the angle between the clonal boundary and the cavity floor (Fig. 4C,D), consistent with our previous observation (Alarcón and Marikawa, 2003). By contrast, the embryos with alginate gel (n = 47) displayed significant bias (P < 0.001; Fig. 4C). Specifically, in about 60% of the embryos (28/47), the angle between the clonal boundary and the cavity floor was less than 30° (Fig. 4C). The bias towards the orthogonal relationship was also evident when the same data were analyzed by categorizing angles into six ranges (Fig. 4D). In addition, we confirmed by time-lapse videomicroscopy that alginate gel effectively diminished the movement of embryos within the ZP (Fig. 4E), consistent with the recent report by Kurotaki et al. (2007). These results suggest that the prevention of embryo rotation within the ZP increases the incidence of the orthogonal relationship between the Em–Ab axis and the clonal boundary of the two-cell stage blastomeres, further supporting the mechanical constraint model. Notably, such significant tendency of the orthogonal relationship is comparable to the cases reported by Piotrowska et al. (2001), raising the possibility that the rotation of embryos within the ZP was absent or minimum in their study.

Fig. 4.

The clonal boundary between the two-cell stage blastomeres tends to lie orthogonal to the Em–Ab axis when the rotation of the embryo within the ZP is prevented. A: A schematic diagram describing how to fill the perivitelline space of the DiI-labeled embryos with alginate gel (see text for details). B: Two examples of early blastocysts that were derived from alginate-filled, two-cell stage embryos. Left panels are bright field images, middle panels are fluorescence images showing the distribution of DiI-labeled cells, and right panels are overlay of the two images with projected lines for the blastocyst cavity floor (black broken line) and the boundary between the labeled and nonlabeled cells (white broken line). C: A graph showing the occurrence of angles (θ in A) in the alginate-filled embryos (gray bars; n = 47) and control embryos (white bars; n = 44). The angles are categorized into three ranges. D: The same data as presented in (C), with the angles categorized into six ranges. E: Examples of control (top two rows) and alginate-filled (bottom two rows) embryos to show that alginate gel diminishes the movement of embryos within the ZP. The embryo together with the attached polar body (arrowhead) tends to rotate within the ZP during early cleavages in control cases, while such rotation is markedly less in alginate-filled cases. From left to right, columns represent the two-cell, the early eight-cell, the late eight-cell, and the beginning of the blastocyst stages.

ME-Vegetal Blastomeres Are Not Inclined to Contribute to the Abembryonic Half of the Blastocyst

Recent studies (Piotrowska-Nitsche and Zernicka-Goetz, 2005; Piotrowska-Nitsche et al., 2005) reported that one blastomere in a specific type of four-cell stage embryos contributed almost exclusively to the abembryonic half of the early blastocyst, corroborating the existence of a prepattern in early embryos. Such specific type of four-cell stage embryos, which constituted about 40% of the population, was defined based on the timing and orientation of the second cleavages (Fig. 1C). In those embryos, the earlier second cleavage occurred meridionally (i.e., parallel to the animal–vegetal axis, judged by the location of the second polar body), and the later second cleavage occurred equatorially (i.e., perpendicular or oblique to the animal–vegetal axis). In most cases, the vegetal-most blastomere of the resultant four-cell stage embryos contributed only to the abembryonic half, particularly the mural TE, as shown by lineage tracing (Piotrowska-Nitsche and Zernicka-Goetz, 2005; Piotrowska-Nitsche et al., 2005). Here, we first examined whether such meridional-equatorial sequence of second cleavages (designated as ME) also occur in our population of embryos at a comparable frequency. We then examined whether the vegetal blastomere of the ME type of embryos (designated as ME-vegetal blastomere) contributes mainly to the abembryonic half of the early blastocyst.

Near the end of the two-cell stage, we started observing embryos at intervals of about 30 min to catch them at the three-cell stage. We then separated those embryos in which the earlier second cleavage ran along the animal–vegetal axis (compare Fig. 5A,B). Out of 115 embryos that we caught at the three-cell stage, 55 exhibited the meridional earlier second cleavage. When these embryos reached the four-cell stage, we further separated those embryos in which four blastomeres were arranged in a tetrahedral configuration as ME embryos. Forty-three of them exhibited a distinct tetrahedral configuration (Fig. 5C). Thus, 37.4% (43/115) of the embryos examined were identified as ME embryos. This figure is comparable to that reported in the previous studies (Piotrowska-Nitsche and Zernicka-Goetz, 2005; Piotrowska-Nitsche et al., 2005).

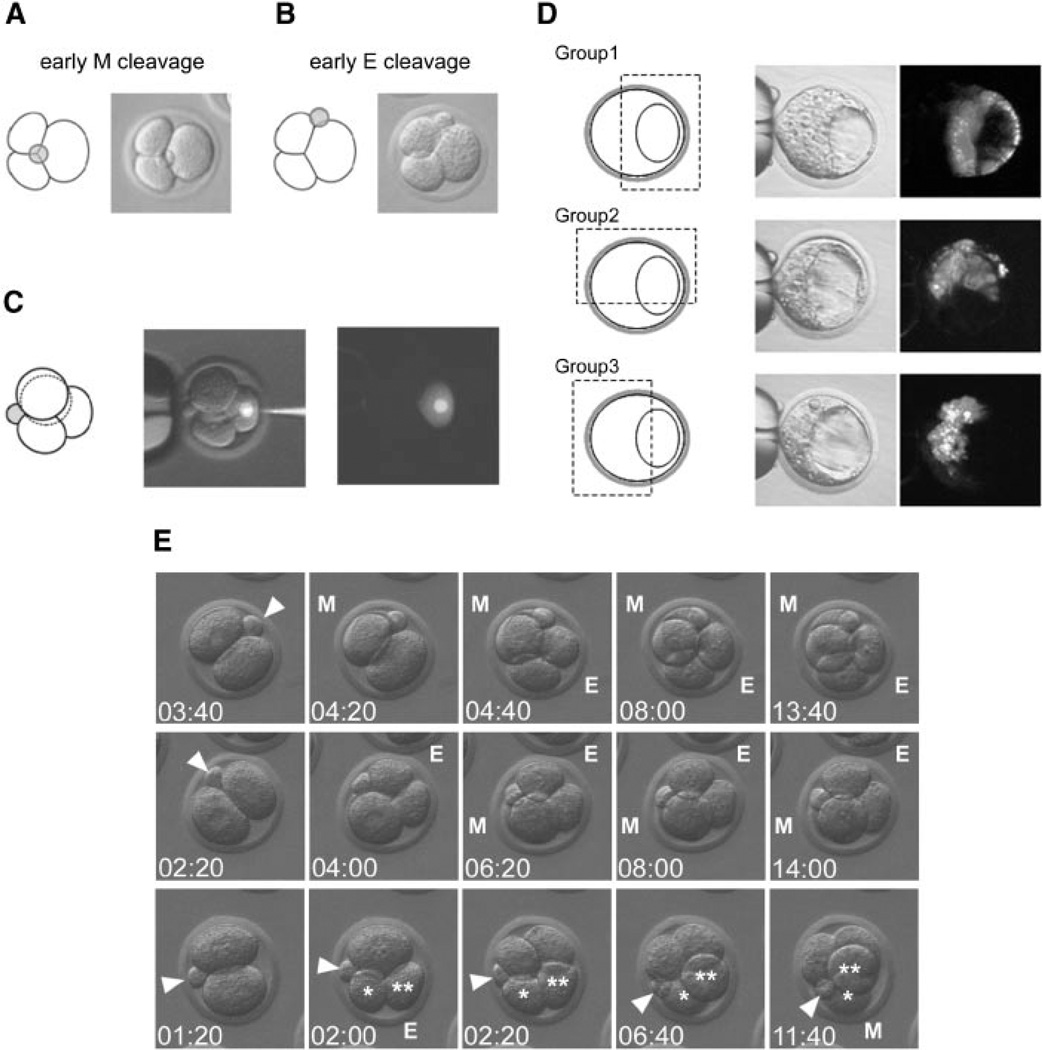

Fig. 5.

Lineage tracing of the vegetal blastomere of the ME-type of four-cell stage embryos. A: A three-cell stage embryo in which the early second cleavage had occurred in a meridional (M) orientation. B: A three-cell stage embryo in which the early second cleavage had occurred in an equatorial (E) orientation. C: The DiI-labeling of the vegetal blastomere in the four-cell stage embryo that had undergone the ME-type of second cleavages. D: The distribution of the descendants of the labeled ME-vegetal blastomere at the early blastocyst stage. The distribution patterns are categorized into three groups (see text for details) and are summarized in Table 2. E: Examples of embryos that were monitored by time-lapse video-microscopy from the two-cell to the late four-cell stages to demonstrate the position of the second polar body relative to the second cleavage planes. In each frame, time is given in hours:minutes after the start of the time-lapse recording. Embryo in the top row is undergoing ME-type of second cleavages, while embryo in the middle row is undergoing EM-type of second cleavages. Embryo in the bottom row shows the early equatorial cleavage producing blastomeres (*,**) that shifted position so that they appear as having undergone the meridional cleavage.

We then labeled with DiI the ME-vegetal blastomere of the ME-type four-cell stage embryos (Fig. 5C), and examined the distribution of its descendants at the early blastocyst stage. The distribution patterns of labeled cells were categorized into three groups with respect to the Em–Ab axis (Fig. 5D). In the first group, the labeled cells were mostly situated in the abembryonic half, which is the foremost situation expected based on the report by Piotrowska-Nitsche et al. (2005). It is critical to point out that this group of embryos can be clearly identified with a conventional fluorescence microscope, as the location of the mural TE is morphologically distinct at the early blastocyst stage. In the second group, the labeled cells were distributed in both the abembryonic and embryonic halves. In the third group, the labeled cells were mostly situated in the embryonic half. Out of 25 ME embryos analyzed, only 3 (12.0%) were categorized in the first group (Table 2), which appears to contradict the previous report by Piotrowska-Nitsche et al. (2005).

TABLE 2.

Distribution of the Descendants of the ME-Vegetal Blastomere in the Early Blastocyst

| Number of embryos with a given distribution patterna |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Labeled blastomere | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Unscoredb |

| ME-vegetal (n=25) | 3 (12%) | 13 (52%) | 7 (28%) | 2 (8%) |

| EM-vegetalc (n=22) | 4 (18%) | 11 (50%) | 5 (23%) | 2 (9%) |

The definitions of the three groups are described in the text and Figure 5D.

In these embryos, multiple blastocyst cavities were present at the early blastocyst stage and the Em–Ab axis was indistinct.

For comparison, we also traced the lineage of the vegetal blastomere of the four-cell stage embryos that had undergone the EM-type of second cleavages. The previous reports (Piotrowska-Nitsche and Zernicka-Goetz, 2005; Piotrowska-Nitsche et al., 2005) indicate that the EM-vegetal blastomere is not biased to contribute to the abembryonic half of the blastocyst.

To seek the source of such contradictory observations, we examined whether the second polar body in our embryos somehow moved more substantially during the second cleavages than the embryos in the previous study (Piotrowska-Nitsche et al., 2005), which may have invalidated the identification of ME embryos in our study. We monitored the location of the second polar body relative to both the early and later second cleavages from the start of the early second cleavage until the end of the four-cell stage (Fig. 5E). In 22 out of 30 embryos examined (73.3%), the second polar body maintained the same position relative to both the second cleavage planes (Fig. 5E, top and middle rows). By contrast, the position of the second polar body relative to the second cleavage planes was not maintained in eight embryos (26.7%). For example (Fig. 5E, bottom row), the early second cleavage was scored as Eat the three-cell stage, but it appeared as M at the late four-cell stage due to the shifting of the blastomeres. However, even when the shifting of the blastomeres is taken into account, the occurrence of the first group (Fig. 5D, Table 2) in our study was still significantly low. Specifically, if the exclusive contribution of the ME-vegetal cell to the abembryonic side is to occur in 80% of the cases based on the previous report (Piotrowska-Nitsche et al., 2005), and also if we are able to identify valid ME embryos at 73.3% of the cases (see above), then the expected occurrence of the first group in our study should be 58.6%, that is, 14 or 15 embryos out of 25 embryos examined. Nonetheless, the actual occurrence of the first group was 12.0%, that is, 3 out of 25 embryos (Table 2), which is significantly lower than what is expected (Chi-square test, P < 0.00001). Therefore, in contrast to the previous report, the ME-vegetal blastomere exhibited no tendency to contribute to the abembryonic half of the early blastocyst.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we showed that the two blastomeres of the two-cell stage embryos were positioned along the longest diameter of the ellipsoidal ZP, and that the Em–Ab axis of the early blastocyst tended to align with the longest diameter when the shape of the ZP was more ellipsoidal than spherical. We also showed that the lineages of the two-cell stage blastomeres correlated with the Em–Ab axis only when the rotation of the embryo within the ZP was blocked by alginate gel. Recently, Kurotaki et al. (2007) reported similar results that the Em–Ab axis of the blastocyst aligns with the ellipsoidal shape of the ZP but is not specified by the lineages of the two-cell stage blastomeres. They showed by time-lapse recording of developing embryos as well as by marking of the ZP, that the Em–Ab axis of the blastocyst tended to lie perpendicularly to the boundary between the two-cell stage blastomeres, that is, the first cleavage plane. However, they also showed by time-lapse recording of the positions of all nuclei from the two-cell to the blastocyst stages that the lineages of the two-cell stage blastomeres had no relationship with the Em–Ab axis. Kurotaki et al. (2007) demonstrated that the lineages of the two-cell stage blastomeres became segregated between the embryonic and abembryonic halves only when the embryos were embedded in alginate gel. The results of our present study are totally consistent with those of Kurotaki et al. (2007), further supporting the mechanical constraint model.

In our previous study (Alarcón and Marikawa, 2003), we reported that the clonal boundary between the descendants of labeled and nonlabeled two-cell stage blastomeres displayed no relationship with the Em–Ab axis of the blastocyst. Our conclusion was contradictory to the preceding study of another group, who showed that the clonal boundary tended to lie orthogonal to the Em–Ab axis, using a similar blastomere-labeling method (Piotrowska et al., 2001). Our previous study was criticized for potential flaws, which were implicated to be the reason why we would not be able to detect the orthogonal relationship between the clonal boundary and the Em–Ab axis (Zernicka-Goetz, 2004; Gardner, 2005; Piotrowska-Nitsche and Zernicka-Goetz, 2005). For example, we labeled the two-cell stage embryos only on one blastomere, instead of two, and assessed the clonal boundary at the blastocyst stage by conventional fluorescence microscopy, instead of confocal microscopy. In spite of such criticisms, the present study confirms that our method is adequate enough to detect the orthogonal relationship if such a relationship indeed exists, as in the cases when embryos are embedded in alginate gel (Fig. 4). This indicates that the lack of confocal analysis or simultaneous labeling of two blastomeres cannot be attributed to the reason why we did not observe any relationship in our previous study, and suggests that the contradictory observations on the lineages of the two-cell stage blastomeres are unlikely to be due to the differences in the labeling and observation techniques.

Instead, the source of contradictions is more likely to be the differences in the extent of embryo rotation within the ZP, as discussed by Hiiragi et al. (2006). When the embryos do not rotate significantly within the ZP, the clonal boundary of the two-cell stage blastomeres appears to lie orthogonal to the Em–Ab axis, as shown by the alginate experiments (Fujimori et al., 2003; Kurotaki et al., 2007; the present study). The extent of embryo rotation may vary depending on the mouse strains or culture conditions. The embryos of the Pathology Oxford (PO) strain do not rotate significantly within the ZP (Gardner, 2001, 2006), which may be due to a matrix called the cortical granule envelope (CGE) occupying the perivitelline space (Hoodbhoy et al., 2001). On the other hand, Motosugi et al. (2005) and Kurotaki et al. (2007) reported significant rotation of embryos within the ZP for different mouse strains, which did not exhibit the orthogonal relationship between the clonal boundary and the Em–Ab axis. It is important to note that in the mechanical constraint model, the ellipsoidal shape of the ZP biases the orientation of the two-cell stage embryo and the location of the blastocyst cavity, but it does not affect the extent of embryo rotation within the ZP (Fig. 1B). Whether an embryo rotates significantly or not appears to be affected by other factors, as listed above. Such factors may be different among research groups and may be the source of apparent contradictions.

Mechanical constraints that are applied exogenously can also influence the orientation of the Em–Ab axis. When embryos were compressed by agar gels from the two-cell to the blastocyst stages, the blastocyst cavity almost always formed at one end of the elongated shape of embryos, regardless of the location of the first cleavage plane (Motosugi et al., 2005). In unmanipulated embryos, the ellipsoidal ZP is likely to exert weaker but significant mechanical constraint to influence the Em–Ab axis, as shown by Kurotaki et al. (2007) and in the present study. On the other hand, Gardner (2007) showed that the correlation between the first cleavage plane and the Em–Ab axis still existed even after the ZP had been removed at the morula stage. Although this observation was presented as evidence against the mechanical constraint model, it is possible that the ellipsoidal ZP, particularly with the CGE in the PO strain, may have already molded an elongated shape in the embryo by the morula stage, which later led to the localized formation of the blastocyst cavity.

Another case against the mechanical constraint model is that the alignment of the Em–Ab axis across the first cleavage plane is not always prominent even when the shapes of embryos are significantly constricted (Gardner, 2001, 2005). Specifically, examples of two embryos were presented by Gardner (2005), in which one embryo displayed a less orthogonal relationship between the first cleavage plane and the Em–Ab axis compared to the other embryo, even though the former had a more conspicuous constriction than the latter. However, it is not clear how often these types of embryos were observed in the study. A mechanical constraint is likely to bias, but not determine, the location of the blastocyst cavity. Thus, the tendency to display the orthogonal relationship relative to the extent of constriction can only be revealed by statistical analyses of sufficient numbers of embryos. In this respect, it is possible to pick out some examples even in our embryos (Fig. 3E and Table 1), which are similar to the situation presented by Gardner (2005). Namely, among 25 constricted embryos (i.e., ZP diameter ratio was <0.95), 10 embryos exhibited a less orthogonal relationship (i.e., they were in the 31°–60° or 61°–90° angle categories). Among 16 nonconstricted embryos (i.e., ZP diameter ratio was ≥0.95), 6 embryos exhibited a more orthogonal relationship (i.e., they were in the 0°–30° angle category). Nevertheless, when all the examined embryos are analyzed statistically, it is evident that the ellipsoidal shape of ZP significantly correlates with the orthogonal relationship.

In the present study, we also evaluated the lineage of the ME-vegetal blastomere of the four-cell stage embryos. The previous report of another group indicated that the ME-vegetal blastomere almost exclusively contributed to the mural TE of the blastocyst (Piotrowska-Nitsche et al., 2005). However, our result shows that the lineage of the ME-vegetal blastomere was not biased toward the mural TE, but rather randomly with respect to the Em–Ab axis. Importantly, the ME embryos in both studies were identified by similar procedures, that is, the order of cleavages was determined by observing embryos at intervals of 20–40 min, and the orientations of cleavages were determined relative to the position of the second polar body (Piotrowska-Nitsche et al., 2005). Also, similarly, the ME-vegetal blastomere was recognized as the blastomere in ME embryos that is located furthest away from the polar body (Piotrowska-Nitsche et al., 2005). Nonetheless, the outcome of the two studies is immensely different. While the cause of such discrepancy is unclear, the restricted lineage of the ME-vegetal blastomere towards the mural TE is unlikely to be a universal rule for all mouse embryos. Thus, any further studies on the molecular and biochemical properties of the ME-vegetal blastomere (e.g., Torres-Padilla et al., 2007) should be accompanied by concomitant lineage analyses in order to acquire information of biological significance.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Takashi Hiiragi and Toshihiko Fujimori for helpful advice on time-lapse videomicroscopy of live mouse embryos. We also thank Toshihiko Fujimori for sharing his data with the authors before publication. We are grateful to Yoshio Masui for critical discussion on embryonic development. This study was supported by the NIH grants (HD050475 and P20RR016467 to V.B.A. and HD040208 to Y.M.).

REFERENCES

- Alarcón VB, Marikawa Y. Deviation of the blastocyst axis from the first cleavage plane does not affect the quality of mouse postimplantation development. Biol Reprod. 2003;69:1208–1212. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.018283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alarcón VB, Marikawa Y. Unbiased contribution of the first two blastomeres to mouse blastocyst development. Mol Reprod Dev. 2005;72:354–361. doi: 10.1002/mrd.20353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beddington RSP, Robertson EJ. Axis development and early asymmetry in mammals. Cell. 1999;96:195–209. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80560-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chroscicka A, Komorowski S, Maleszewski M. Both blastomeres of themouse 2-cell embryo contribute to the embryonic portion of the blastocyst. Mol Reprod Dev. 2004;68:308–312. doi: 10.1002/mrd.20081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Committee to Revise the Guide, Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources Council, Commission on Life Sciences, National Research Council. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. 7th edition. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Fujimori T, Kurotaki Y, Miyazaki J, Nabeshima Y. Analysis of cell lineage in two- and four-cell mouse embryos. Development. 2003;130:5113–5122. doi: 10.1242/dev.00725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner RL. Specification of embryonic axes begins before cleavage in normal mouse development. Development. 2001;128:839–847. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.6.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner RL. Application of alginate gels to the study of mammalian development. Methods Mol Biol. 2004;254:383–392. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-741-6:383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner RL. The case for prepatterning in the mouse. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today. 2005;75:142–150. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.20038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner RL. Weaknesses in the case against prepatterning in the mouse. Reprod BioMed Online. 2006;12:144–149. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)60853-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner RL. The axis of polarity of the mouse blastocyst is specified before blastulation and independently of the zona pellucida. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:798–806. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiiragi T, Alarcón VB, Fujimori T, Louvet-Vallée S, Maleszewski M, Marikawa Y, Maro B, Solter D. Where do we stand now? Mouse early embryo patterning meeting in Freiburg, Germany, (2005) Int J Dev Biol. 2006;50:581–586. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.062181th. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoodbhoy T, Dandekar P, Calarco P, Talbot P. p62/p56 are cortical granule proteins that contribute to the formation of the cortical granule envelope and play a role in mammalian preimplantation development. Mol Reprod Dev. 2001;59:78–89. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurotaki Y, Hatta K, Nakao K, Nabeshima Y, Fujimori T. Blastocyst axis is specified independently of early cell lineage but aligns with the ZP shape. Science. 2007;316:719–723. doi: 10.1126/science.1138591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motosugi N, Bauer T, Polanski Z, Solter D, Hiiragi T. Polarity of the mouse embryo is established at blastocyst and is not prepatterned. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1081–1092. doi: 10.1101/gad.1304805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piotrowska K, Wianny F, Pedersen RA, Zernicka-Goetz M. Blastomeres arising from the first cleavage division have distinguishable fates in normal mouse development. Development. 2001;128:3739–3748. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.19.3739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piotrowska-Nitsche K, Zernicka-Goetz M. Spatial arrangement of individual 4-cell stage blastomeres and the order in which they are generated correlate with blastocyst pattern in the mouse. Mech Dev. 2005;122:487–500. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2004.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piotrowska-Nitsche K, Perea-Gomez A, Haraguchi S, Zernicka-Goetz M. Four-cell stage mouse blastomeres have different developmental properties. Development. 2005;132:479–490. doi: 10.1242/dev.01602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossant J, Tam PPL. Emerging asymmetry and embryonic patterning in early mouse development. Dev Cell. 2004;7:155–164. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam PPL, Loebel DAF, Tanaka SS. Building the mouse gastrula: Signals, asymmetry and lineages. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2006;16:419–425. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Padilla ME, Parfitt DE, Kouzarides T, Zernicka-Goetz M. Histone arginine methylation regulates pluripotency in the early mouse embryo. Nature. 2007;445:214–218. doi: 10.1038/nature05458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waksmundzka M, Wisniewska A, Maleszewski M. Allocation of cells in mouse blastocyst is not determined by the order of cleavage of the first two blastomeres. Biol Reprod. 2006;75:582–587. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.106.053165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka Y, Ralston A, Stephenson RO, Rossant J. Cell and molecular regulation of the mouse blastocyst. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:2301–2314. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zernicka-Goetz M. First cell fate decisions and spatial patterning in the early mouse embryo. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2004;15:563–572. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zernicka-Goetz M. The first cell-fate decisions in the mouse embryo: Destiny is a matter of both chance and choice. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2006;16:406–412. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]