Abstract

The sympathetic nervous system (SNS) arises from neural crest (NC) cells during embryonic development and innervates the internal organs of vertebrates to modulate their stress response. NRP1 and NRP2 are receptors for guidance cues of the class 3 semaphorin (SEMA) family and are expressed in partially overlapping patterns in sympathetic NC cells and their progeny. By comparing the phenotypes of mice lacking NRP1 or its ligand SEMA3A with mice lacking NRP1 in the sympathetic versus vascular endothelial cell lineages, we demonstrate that SEMA3A signalling through NRP1 has multiple cell-autonomous roles in SNS development. These roles include neuronal cell body positioning, neuronal aggregation and axon guidance, first during sympathetic chain assembly and then to regulate the innervation of the heart and aorta. Loss of NRP2 or its ligand SEMA3F impaired sympathetic gangliogenesis more mildly than loss of SEMA3A/NRP1 signalling, but caused ectopic neurite extension along the embryonic aorta. The analysis of compound mutants lacking SEMA3A and SEMA3F or NRP1 and NRP2 in the SNS demonstrated that both signalling pathways cooperate to organise the SNS. We further show that abnormal sympathetic development in mice lacking NRP1 in the sympathetic lineage has functional consequences, as it causes sinus bradycardia, similar to mice lacking SEMA3A.

Keywords: Neuropilin, Semaphorin, Neural crest cell, Sympathetic nervous system, Heart, Aorta, Mouse

Highlights

► NRP1 and NRP2 are co-expressed in sympathetic neurons and their precursors. ► SEMA3A signals through NRP1 to regulate sympathetic gangliogenesis and axon guidance. ► SEMA3F signals through NRP2 to regulate sympathetic axon guidance. ► SEMA3A/NRP1 and SEMA3F/NRP2 act synergistically in sympathetic nervous system patterning. ► Abnormal sympathetic innervation of the heart leads to bradycardia in NRP1 mutants.

Introduction

The sympathetic nervous system (SNS) innervates the internal organs of vertebrates to modulate their performance in response to stress. Within the cardiovascular system, it innervates the smooth muscle layers of blood vessels, cardiac muscles and nodes of the heart to control blood pressure and heart rate. The cell bodies of sympathetic neurons reside in ganglia; in the trunk, the ganglia are arranged in bilateral sympathetic chains parallel to the vertebral column and are joined to the cervical ganglia at their rostral end.

The sympathetic neurons arise from neural crest (NC) cells, which delaminate from the developing neural plate at cranial and trunk level to give rise to diverse cell types in appropriate locations (reviewed in Le Douarin and Kalcheim (1999)). In the trunk, three main waves of migrating NC can be distinguished, and their migratory path correlates with their differentiation potential (reviewed by Ruhrberg and Schwarz (2010)). The earliest wave of trunk NC cells travels ventromedially in the intersomitic furrow to seed the sympathetic ganglia at the dorsal aorta (Schwarz et al., 2009b). NC cells in the intermediate wave also migrate ventromedially, but they follow a path through the anterior sclerotome of each somite (e.g., Bronner-Fraser, 1986; Loring and Erickson, 1987; Rickmann et al., 1985). These cells either arrest in the somite to form the sensory neurons of the dorsal root ganglia (DRG) or continue towards the dorsal aorta to populate the sympathetic ganglia. Finally, the last wave of trunk NC migration follows a dorsolateral pathway close to the ectoderm and gives rise to the melanocytes in the skin (e.g., Erickson et al., 1992).

A diverse range of attractive and repulsive cues guide migrating trunk NC cells (reviewed by Ruhrberg and Schwarz (2010)). Amongst these, the class 3 semaphorins SEMA3A and SEMA3F are particularly important for NC cells with a neuroglial fate (Gammill et al., 2006; Roffers-Agarwal and Gammill, 2009; Schwarz et al., 2009a, 2009b). SEMA3A/NRP1 signalling controls the dorsoventral distribution of neuroglial NC cells. Thus, loss of SEMA3A or NRP1 allows neuroglial NC cells to migrate dorsolaterally onto the melanocytic pathway or ventrally into the intersomitic furrows, where they travel alongside blood vessels (Schwarz et al., 2009b). This abnormal migration results in disorganised DRGs and ectopic sympathetic neurons (Kawasaki et al., 2002; Schwarz et al., 2009b). However, it is not yet known if loss of NRP1 signalling in NC cells alone is responsible for ectopic sympathetic neuron placement, or if abnormal vascular patterning in NRP1 knockouts aggravates this defect by misguiding sympathetic NC cells.

At the dorsal aorta, sympathetic NC cells intermix along the rostrocaudal axis and aggregate into loose clusters of neuronal precursors, the primary sympathetic ganglia (Kasemeier-Kulesa et al., 2005; Yip, 1986a). Eventually, the cells in the primary ganglia migrate a short distance dorsally toward the ventral roots, where they form the secondary, i.e., definitive sympathetic ganglia, that receive synaptic input from preganglionic sympathetic axons (Kirby and Gilmore, 1976). As the sympathetic precursors differentiate into postmitotic neurons, they begin to express dopamine-beta hydroxylase (DBH) and tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) for noradrenaline synthesis and extend axons between them to form the sympathetic chains. Eventually, they also extend axons to their target organs, including, amongst others, the heart and aorta. The impact of NRP1 deficiency on sympathetic axon guidance and postnatal sympathetic innervation of the heart or other target organs has not yet been investigated due to the embryonic lethality of full Nrp1 knockouts. Yet, it is likely that NRP1 plays a major role, as loss of SEMA3A impairs myocardial innervation (Ieda et al., 2007).

In contrast to SEMA3A/NRP1 signalling, SEMA3F/NRP2 signalling regulates the anteroposterior distribution of NC cells. Thus, neuroglial NC cells migrate uniformly through both the anterior and posterior sclerotome in mice lacking SEMA3F or its receptor NRP2 (Gammill et al., 2006). By playing different roles in NC cell guidance, SEMA3A and SEMA3F act synergistically to ensure proper DRG segmentation (Roffers-Agarwal and Gammill, 2009; Schwarz et al., 2009a). In vitro, NRP2 also mediates the repulsive activity of SEMA3F on sympathetic axons (Chen et al., 1998; Giger et al., 2000, 1998). However, it is not known if NRP2 is expressed in sympathetic NC cells prior to their neuronal differentiation, or if SEMA3F signalling through NRP2 contributes to SNS assembly or axon guidance in vivo. Moreover, the early lethality of NRP1/NRP2 double knockouts prior to neuronal differentiation has hampered the investigation of whether NRP1 and NRP2 cooperate to control sympathetic patterning.

Using cell-type-specific gene targeting, we show here that NRP1 acts cell autonomously in the NC lineage to control sympathetic NC cell migration and axon guidance towards the heart and aorta, independently of its role in blood vessel patterning. We further show that NRP2 is co-expressed with NRP1 during SNS development and that mice lacking NRP2 or its ligand SEMA3F have mild SNS defects similar to each other, but different to those in mice lacking NRP1 or SEMA3A. Finally, we created compound mutants deficient in both neuropilins or both semaphorins to show that the SEMA3A/NRP1 and SEMA3F/NRP2 pathways synergistically pattern the SNS.

Materials and methods

Animals

To obtain mouse embryos of defined gestational ages, mice were mated in the evening, and the morning of vaginal plug formation was counted as 0.5 day post coitum (dpc). To stage-match embryos within a litter, or between litters from different matings, we compared somite numbers. Mice carrying a Sema3a-, Sema3f-, Nrp1- or Nrp2-null allele have been described (Giger et al., 2000; Kitsukawa et al., 1997; Sahay et al., 2003; Taniguchi et al., 1997). Conditional null mutants for Nrp1 Nrp1fl/fl; Gu et al., 2003) were mated to mice expressing CRE recombinase under the control of the endothelial-specific Tie2 promoter (Tie2-Cre; Kisanuki et al., 2001) or the neural crest-specific promoter Wnt1 (Wnt1-Cre; Jiang et al., 2000). Mouse husbandry was performed in accordance with UK Home Office and institutional guidelines. Genotyping protocols can be supplied on request.

Immunolabelling and in situ hybridisation

Samples were fixed in 4% formaldehyde in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and processed as wholemounts or cryosectioned at a thickness of 20 μm. The following primary antibodies were used: rabbit anti-p75 (gift of Dr G. Schiavo, Cancer Research UK, London; Schwarz et al., 2009b), rabbit anti-tyrosine hydroxylase (Millipore), mouse anti-MASH1 (BD Pharmingen), goat anti-NRP1 or NRP2 (R&D Systems) and rabbit anti-NRP1 (Epitomics). Secondary antibodies used were: Alexa488- or Alexa594-conjugated goat anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgGs (Invitrogen), Cy3-conjugated rabbit anti-goat and FITC-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG Fab fragments (Jackson). In some experiments, we used Cy3-conjugated anti-a-smooth muscle alpha actin (Sigma). Fluorescently labelled sections were mounted in Mowiol, imaged with the LSM510 or LSM710 laser scanning confocal microscope (Zeiss). For immunohistochemistry, TH primary antibody was detected by horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (DAKO) and diaminobenzidine and hydrogen peroxide (Sigma). In situ hybridisation was performed with digoxigenin-labelled riboprobes transcribed from cDNA encoding Mash1 (Cau et al., 1997), Isl1, Sema3a, Sema3f or Sox10 (Schwarz et al., 2008a, 2009a) and detected with alkaline phosphatase (AP)-conjugated anti-digoxigenin Fab fragment. HRP- or AP-labelled samples were visualised by conventional light microscopy, using an MZ16 microscope (Leica) equipped with a Micropublisher 3.3 camera (Q Imaging) and OpenLab software (Improvision). All images were processed with Adobe Photoshop CS4 software (Adobe Inc).

Quantitation of target organ innervation by sympathetic fibres

We determined the number of TH-positive fibres in the superficial myocardial wall (subepicardium; defined as a 45 μm-thick tissue region beneath the epicardium), the myocardial wall adjacent to the ventricular cavity (subendocardium; defined as a 45 μm-thick tissue region beneath the endocardium) and the intervening myocardium in 3 non-consecutive 20 μm cryosections and calculated the mean number of fibres per mm2. To determine the relative difference in subepicardial to subendocardial innervation, we divided the subendocardial fibre density by the subepicardial fibre density of each sample to obtain a normalised subendocardial innervation ratio and then compared the mean ratios of mutant and wild types. To determine the number of sympathetic axons in the aortic wall of each sample, we counted TH-positive fibres in 30 consecutive 20 μm cryosections and calculated the mean number of fibres per section and compared mutant and wild type values.

Electrophysiology studies

Mice were anaesthetised with 1.5% isoflurane and a lead II ECG was recorded and filtered between 0.5 and 500 Hz at a sampling rate of 2 kHz (Powerlab and Chart software; AD Instruments, Oxford). For each mouse, we obtained the mean R–R interval and other electrocardiography (ECG) parameters from a two-minute continuous recording.

Statistical analyses

To examine if the difference between two independent data sets was statistically significant, we carried out unpaired Student's T-tests with GraphPad Prism v4 (GraphPad Software).

Results and discussion

Expression pattern of NRP1 and NRP2 in NC cells and sympathetic neurons

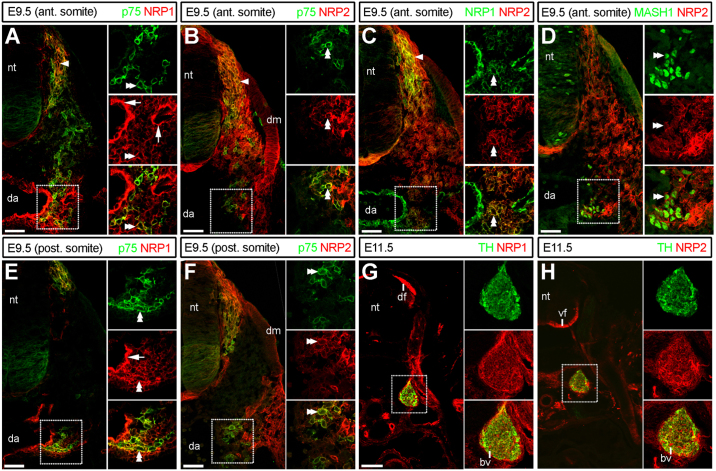

We recently reported that neuroglial NC cells in the intermediate wave express both NRP1 and NRP2 (Schwarz et al., 2009a, 2009b). Using double immunolabelling with antibodies for NRP1 and the NC marker p75 neurotrophin receptor, we now show that NRP1 expression is maintained in NC cells near the dorsal aorta at the level of both the anterior and posterior somite, supporting a cell-autonomous role for NRP1 in the sympathetic lineage (double arrowheads, Fig. 1A and E). NRP1 was also expressed in the p75-negative peri-aortic mesenchyme (Fig. 1A and E). Finally, NRP1 was expressed in the endothelial cells of the aorta and other blood vessels, raising the possibility that vascular NRP1 expression may also impact on sympathetic neuronal development (white arrows, Fig. 1A and E).

Fig. 1.

Co-expression of neuropilins in the NC lineage. (A–F) Transverse cryosections of E9.5 or E11.5 wild-type embryos at forelimb level, immunolabelled for NRP1 or NRP2 and markers for NC cells (p75), sympathetic precursors (MASH1) or sympathetic neurons (TH); half of each section is shown; areas in dashed boxes are shown in higher magnification as separate channels and overlays to the right of each panel. Sympathetic NC cells aggregating at the dorsal aorta were NRP1- and NRP2-positive at both anterior (double arrowheads; A–C) and posterior (double arrowheads; E and F) somite level; migratory intermediate wave NC cells were also NRP1- and NRP2-positive (arrowheads; A,B,C); NRP1-postive vascular endothelium is indicated (white arrows in A and E). (G and H) Sympathetic neurons in the definite sympathetic ganglia were NRP1- and NRP2-positive. Abbreviations: neural tube, nt; DRG anlagen, d; dermomyotome, dm; dorsal funiculus, df; ventral funiculus, vf; dorsal aorta, da; blood vessel, bp. Scale bars: A–F: 100 μm, G and H: 200 μm.

Similar to NRP1, NRP2 was expressed by p75-positive NC cells in the intermediate wave (double arrowheads, Fig. 1B) (Gammill et al., 2006; Schwarz et al., 2009a) and in a subset of p75-positive sympathetic NC cells at the aorta, both at the level of the anterior and posterior somite (double arrowheads, Fig. 1B and F). In addition, NRP2 was expressed in the somitic and peri-aortic mesenchyme and the dermomyotome (Fig. 1B and F). Double labelling with antibodies to NRP1 and NRP2 showed co-expression of both neuropilins in migratory NC cells and sympathetic precursors at the dorsal aorta (Fig. 1C, arrowhead and double arrowheads, respectively). Double labelling for the transcription factor MASH1 further confirmed that NRP2 was expressed in early sympathetic neuronal precursors at the aorta (double arrowheads, Fig. 1D). At E11.5, both NRP1 and NRP2 were expressed strongly in tyrosine hydroxylase (TH)-positive sympathetic neurons in the definite sympathetic ganglia (boxed areas, Fig. 1G and H), which at this stage are located further away from the dorsal aorta, near the spinal nerves (compare Fig. 1A and E with Fig. 1G and H). The process of secondary migration has therefore taken place by E11.5 in the mouse.

To delineate the expression pattern of the neuropilin ligands relative to sympathetic neuronal development, we performed in situ hybridisation on adjacent sections for Sema3a, Sema3f and the transcription factor Isl1 between E10.5 and E12.5 (Fig. S1). At E10.5, Sema3a was expressed in the dermomyotome, neural tube, forelimb and ventral to the aorta; in contrast, the area dorsal to the aorta, where sympathetic NC condense into the primary sympathetic ganglia, appeared to express lower levels of Sema3a (Fig. S1B; see Kawasaki et al., 2002). This expression pattern is consistent with a role for SEMA3A in guiding sympathetic NC to the aorta by surround repulsion. Sema3f was expressed in a similar pattern to Sema3a, except that it additionally appeared to be expressed weakly in the aortic wall (arrow in Fig. S1C). However, the observation that NRP2-positive NC cells contribute to the primary sympathetic ganglia suggests that SEMA3F-mediated repulsion from the aorta is not a significant regulator of sympathetic development at this stage. At E11.5 and E12.5, the sympathetic ganglia can be recognised by their expression of Isl1 (Fig. S1D and G). Consistent with a previous report (Kagoshima and Ito, 2001), SEMA3A and SEMA3F were strongly expressed ventral to the aorta, in the developing lung (Fig. S1H,I). In addition, low-level expression of Sema3a and Sema3f around the aorta was consistent with the idea that these semaphorins regulate sympathetic patterning after the period of primary gangliogenesis (black arrows in Fig. S1E,F and H,I). Together, the expression patterns of the neuropilins and their ligands raise the possibility that NRP1 and NRP2 synergise to control SNS development by acting as receptors for SEMA3A and SEMA3F, respectively.

SEMA3A signalling through NRP1 regulates sympathetic gangliogenesis and neurite extension

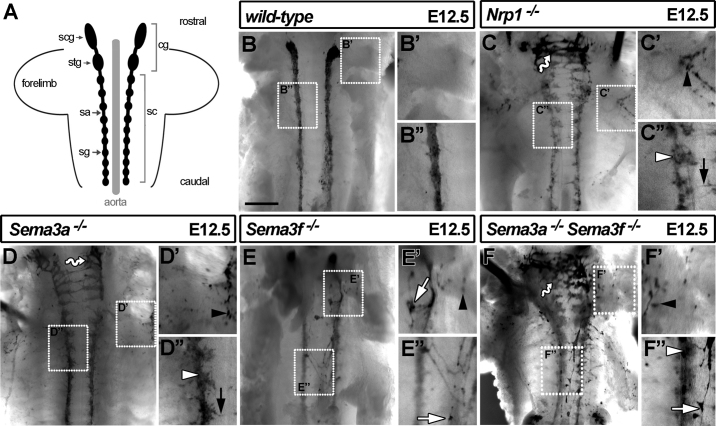

The sympathetic ganglia and interconnecting axon tracts (Fig. 2A) can be visualised after wholemount immunolabelling for TH in flatmount preparation (Fig. 2B; superior cervical ganglia were removed during dissection). Using this method, we confirmed a previous report (Kawasaki et al., 2002), which showed that the SNS in Nrp1-null mutants is disorganised at E12.5 (Fig. 2B and C), the latest time point at which these mutants are viable in the outbred CD1 background (in the inbred C57/Bl6 background, NRP1 loss leads to death by E10.5; Jones et al., 2008). We then extended the previous report by defining in more detail the SNS defects of Nrp1-null mutants and by comparing them to Sema3a-null mutants.

Fig. 2.

Loss of SEMA3A and SEMA3F disrupts SNS patterning. (A) Schematic of the SNS in a E12.5 mouse embryo; sympathetic neurons cluster into sympathetic ganglia (sg) that align either side of the aorta; they are connected by sympathetic axons (sa) into the trunk sympathetic chains (sc) and to the cervical ganglia (cg), including the stellate ganglia (stg) and superior cervical ganglia (scg). (B–F) Ventral view of the SNS in E12.5 embryos after wholemount TH immunolabelling and removal of the internal organs and scg; areas in dashed boxes are shown in higher magnification to the right of each panel. Whilst ganglia in wild-types (B) appeared compact, ganglia were more dispersed in Nrp1-null (C) and Sema3a-null (D) mutants (white arrowheads in C″ and D″); these genotypes also contained chains of medially placed neurons (wavy arrows in C,D), ectopic axons extending across the midline (black arrows in C″ and D″) and ectopic distal neurons (black arrowheads in C′ and D′). Sema3f-null mutants (E) contained ectopic neurons on top of the aorta (white arrows in E′ and E″) and extended aberrant axons on top of the aorta (E″). The ganglia of Sema3a/Sema3f-null mutants (F) were poorly compacted (white arrowhead in F″), and there were medially (wavy arrow in F) and distally displaced neurons (arrowhead in F′); ectopic neurons and axons were present on top of the aorta (white arrow in F″). Scale bar: 500 μm.

First, we observed that the sympathetic ganglia of Nrp1-null mutants were more loosely organised than the ganglia of wild-type littermates (white arrowhead, Fig. 2C′; compare Fig. 2B″ with C″). This phenotype was reminiscent of the reduced DRG compaction in Nrp1-null mutants (Kitsukawa et al., 1997). Second, ectopic neurons were present in a medial position, particularly at cervical level, and they were arranged in chain-like structures between the opposing sympathetic cords (wavy arrow, Fig. 2C). Third, ectopic sympathetic neurons were positioned distally to the main ganglia, particularly at the level of the stellate ganglia (arrowhead, Fig. 2C′). Fourth, neurites extended across the midline (black arrow, Fig. 2C″). Finally, as expected but not shown before, mutants lacking SEMA3A phenocopied the sympathetic defects of Nrp1-null mutants, including distal ectopic neurons, abnormal neurite extension across the midline and ectopic medial neurons at cervical level (Fig. 2D, D′,D″). SEMA3A signalling through NRP1 therefore controls cell body positioning, neuronal aggregation and neurite extension during SNS development.

The appearance of ectopic sympathetic neurons in distal locations is thought to be a direct consequence of defective ventral migration of sympathetic NC cells in the absence of SEMA3A or NRP1 (Schwarz et al., 2009a,b). In contrast, the medial displacement of neurons is better explained by defective migration of sympathetic precursors subsequent to NC cell guidance, either during rostrocaudal intermixing or, perhaps more likely, during the process of secondary migration, which positions the mature sympathetic ganglia in their final location adjacent to the vertebral column (Kirby and Gilmore, 1976). In agreement, medially displaced ganglia have also been described in compound mutants lacking two neuropilin co-receptors for semaphorin signalling, plexin (PLXN) A3 and PLXNA4, but NC migration is normal in these mutants (Waimey et al., 2008). Future studies may wish to examine whether a failure of normal secondary migration in the cervical area is linked to defective guidance of preganglionic sympathetic axons, as they have been proposed to alter the migration of sympathetic ganglion neurons (Yip, 1986a) and rely on region-specific guidance cues that are not present at thoracic or lumbar level (Yip, 1986b).

SEMA3F cooperates with SEMA3A to regulate sympathetic gangliogenesis and neurite guidance

It was previously reported that SEMA3F repels sympathetic axons extending from ganglionic explants (Giger et al., 2000). In support of these in vitro findings, the SNS of Sema3f-null mutants was mildly disorganised, with some distal and medial ectopic neurons as well as neurites that extended abnormally around the aorta (Fig. 2E; visible on top of the aorta in our flatmount preparations). These SNS defects were different to those of Sema3a- or Nrp1-null mutants, where neurites more typically extended towards the opposing sympathetic chain (compare Fig. 2C and D with 2E). Mutants lacking both SEMA3A and SEMA3F combined the SNS defects of the single mutants, with distal ectopic neurons and medially displaced ganglia at cervical level, as well as ectopic ganglia extending neurites on top of the aorta (Fig. 2F). These ectopic neurites may correspond to axons that have strayed from the sympathetic chain before the onset of target innervation, consistent with the finding that SEMA3F and SEMA3A repel sympathetic axons in vitro (Giger et al., 2000) and the observation that most postganglionic sympathetic dendrites develop only postnatally (Voyvodic, 1987). Alternatively, the ectopic neurites may represent dendrites that have extended prematurely and to the wrong targets in the absence of inhibitory semaphorin signalling.

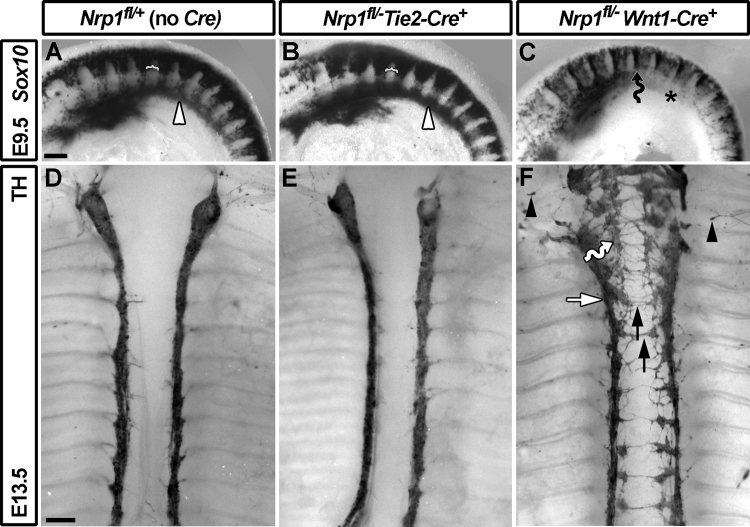

Cell-autonomous requirement for NRP1 in the sympathetic lineage

It was originally proposed that sympathetic chain disorganisation in Nrp1-null mutants is caused by abnormal neuronal progenitor migration rather than a NC defect (Kawasaki et al., 2002). We subsequently demonstrated that defective NC cell migration along blood vessels predates SNS disorganisation (Schwarz et al., 2009b). Yet, it has not previously been addressed whether sympathetic defects were aggravated by vascular defects, which are present in Nrp1-null mutants. To investigate a possible role for NRP1-mediated vessel patterning in SNS assembly, we inactivated a conditional Nrp1-null (floxed) allele with CRE recombinase expressed under the control of the endothelial-specific Tie2 promoter on a heterozygous Nrp1-null background (Nrp1fl/− Tie2-Cre mutants; Gu et al., 2003). However, intermediate wave NC streams containing sympathetic precursors migrated normally in mice lacking endothelial NRP1 (Fig. 3A and B) and their SNS was indistinguishable from that of wild-type littermates at E13.5 (Fig. 3D and E). Consistent with the lack of phenotype in endothelial Nrp1-null mutants, mice lacking the vascular NRP1 ligand VEGF164, a neuropilin-binding isoform of the vascular growth factor VEGF-A (Vegfa120/120 mutants; e.g., Ruhrberg et al., 2002), also assembled normal sympathetic chains at E13.5 (Fig. S2). The lack of a developmental SNS defect in these mutants contrasts with findings for SNS regeneration in adult rats, where VEGF-A signalling promotes sympathetic axon guidance (Marko and Damon, 2008).

Fig. 3.

Loss of NRP1 from the NC, but not endothelial cell lineage, disrupts sympathetic NC migration and sympathetic chain organisation. (A–C) Wholemount in situ hybridisation of E9.5 embryos for Sox10. In wild-types (A) and mutants lacking NRP1 in endothelial cells (B), NC cells migrated normally through the anterior somite, avoiding the posterior somite (white brackets) and aggregated into the primary sympathetic ganglia (white arrowhead). Mutants lacking NRP1 in the NC lineage (C) showed excessive NC cell migration through the intersomitic furrows (black wavy arrow) and delayed assembly of the primary sympathetic ganglia (asterisk). (D–E) Wholemount immunolabelling of E13.5 embryos for TH to visualise the sympathetic chains. In controls (D) and mutants lacking NRP1 in endothelial cells (E), the sympathetic chains appeared to be organised into tight ganglia. In the absence of NRP1 in the NC lineage (F), sympathetic ganglia appeared less compact (white arrow), with medially displaced ganglia (wavy arrow) and ectopic axon extension towards the midline (black arrows); ectopic sympathetic neurons were also present, particularly at cervical level (black arrowheads). Scale bars: A–C, 250 μm; D–F, 500 μm.

In contrast to endothelial Nrp1 mutants, E13.5 mice lacking Nrp1 in the NC lineage (Nrp1fl/− Wnt1-Cre) had SNS defects that were similar to those of full Nrp1 knockouts at E12.5 (Fig. 3C and F). The E13.5 analysis additionally demonstrated that medially displaced neurons aggregated into ectopic ganglia (wavy arrow, Fig. 3F), as in plexin mutants (Waimey et al., 2008). Ectopic neurite extension across the midline, between the sympathetic chains, was also more prominent at E13.5 than at the earlier stage (black arrows, Fig. 3F). This phenotype agrees with the finding that SEMA3A repels sympathetic axons in vitro (Chen et al., 1998; Giger et al., 1998, 2000), but had not previously been described due to the lethality of full Nrp1-null mutants at E12.5. Together, the analysis of tissue-specific Nrp1 mutants shows that NRP1 acts cell-autonomously in the sympathetic NC lineage to regulate cell body positioning, neuronal aggregation and axon guidance in the SNS.

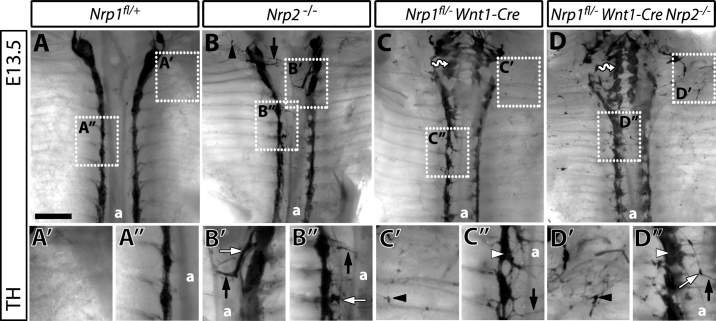

SEMA3F signalling through NRP2 patterns the SNS

It was previously reported that NRP2 is dispensable for SNS development (Waimey et al., 2008). However, we had observed NRP2 expression in sympathetic NC cells and their progeny at the aorta (Fig. 1) and identified an essential role for the NRP2 ligand SEMA3F in SNS patterning (Fig. 2). We therefore re-examined the possibility that NRP2 regulates SNS patterning in vivo by wholemount TH staining of Nrp2-null mutants at E13.5. Consistent with the phenotype of Sema3f-null mutants, Nrp2-null mutants contained some ectopic sympathetic neurons distal to the aorta (black arrowhead, Fig. 4B), ectopic neurites (black arrows, Fig. 4B, B′,B″) and ectopic neurons on top of the aorta (white arrow, Fig. 4B′). SEMA3F signalling through NRP2 is therefore essential for sympathetic axon guidance.

Fig. 4.

NRP1 and NRP2 cooperate to pattern the sympathetic chains. (A–D) Wholemount TH immunolabelling of E13.5 sympathetic chains in littermate embryos from matings of Wnt1-Cre Nrp1+/−Nrp2+/− with Nrp1fl/flNrp2+/− mice; the position of the aorta is indicated with (a); boxed areas are shown at high magnification in (A′–D″). In wild-types (A), areas distal to the chains were free from sympathetic neurons (A′) and chain ganglia were compact (A″). Nrp2-null mutants (B) contained a few ectopic neurons distal to the cervical ganglia (black arrowhead in B), some ganglia were disorganised at both cervical and trunk level (white arrows in B′ and B), and a few axons extended towards or on top of the aorta (black arrows in B,B″). Mutants lacking NRP1 in the NC lineage (C) contained ectopic ganglia in medial positions (wavy arrow in C), distal ectopic neurons (black arrowhead in C′), poorly compacted ganglia (white arrowhead in C″) and axons that projected across the midline (black arrow in C″). The SNS of mutants lacking both NRP2 and NRP1 in the sympathetic lineage (D) contained medial ganglia (wavy arrow in D), distal ectopic neurons (black arrowhead in D′) and dispersed ganglia (white arrowhead in D″), like other types of Nrp1 mutants; they also had ectopic ganglia that extended axons on top of the aorta (white arrow in D″). Scale bar: 500 μm.

To investigate the relationship of NRP1 and NRP2 signalling in SNS patterning, we examined mutants carrying the NC-specific Nrp1-null mutation on a Nrp2-null background. This strategy circumvented the lethality of full Nrp1/Nrp2-null mutants at E10.5 that is caused by insufficient yolk sac vascularisation (Takashima et al., 2002). Thus, E13.5 compound null mutants were recovered at the expected Mendelian ratio (observed frequency 3/40 Nrp1fl/− Wnt1-Cre+; Nrp2−/− in 6 litters, compared to the predicted frequency of 1:16, i.e., 3/48). As observed for compound Sema3a/Sema3f-null mutants, Nrp1fl/− Wnt1-Cre; Nrp2−/− combined the defects of single mutants (compare Fig. 4B, C with D). Specifically, Nrp1fl/− Wnt1-Cre; Nrp2−/− contained ectopic sympathetic neurites around the aorta like single Nrp2-null mutants (black arrow, Fig. 4D″), but also distal ectopic neurons that extended axons (black arrowheads, Fig. 4D′), poorly condensed ganglia (white arrowhead, Fig. 4D″) and medially positioned ganglia (wavy arrow, Fig. 4D), similar to Nrp1 Wnt1-Cre-null mutants.

The phenotype of compound NRP1 and NRP2 mutants suggests that these mutants do not act with partial redundancy to convey SEMA3A signals for SNS development, as they do during vomeronasal axon guidance (Cariboni et al., 2011). Rather, NRP1 and NRP2 have distinct but synergistic functions, similar to the sensory nervous system, where NRP1 conveys SEMA3A and NRP2 conveys SEMA3F signals to control different aspects of NC cell and axon guidance (Gu et al., 2003; Schwarz et al., 2009a, 2008a, 2008b).

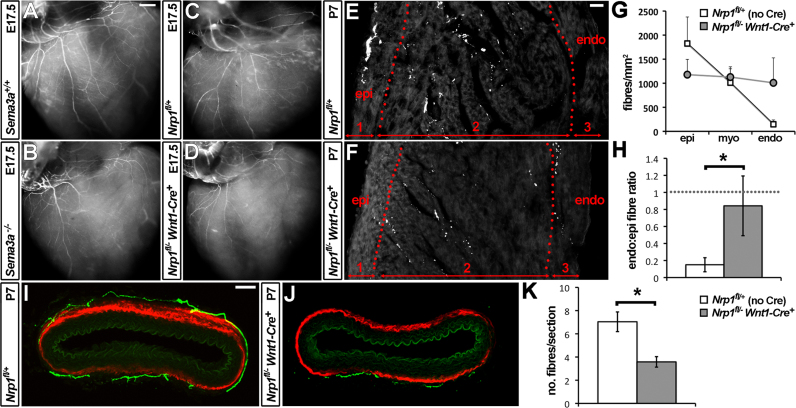

SEMA3A/NRP1 signalling controls sympathetic innervation of the myocardium and aorta

In contrast to full and endothelial specific Nrp1-null mutants, Nrp1fl/− Wnt1-Cre mutants survived embryonic development and were born at normal Mendelian ratios (Table 1). We were therefore able to examine the consequence of NRP1 loss on the sympathetic innervation of target organs. To innervate the heart, sympathetic axons extend from the stellate ganglia and, guided by SEMA3A, invade the working myocardium (Ieda et al., 2007). Accordingly, fewer TH-positive axons are visible on the wholemount heart of E17.5 Sema3a-null mutants compared to littermate wild-types (Fig. 5A and B). Consistent with NRP1 being the SEMA3A receptor in sympathetic axons, fewer TH-positive axons were also visible on the heart of E17.5 Nrp1fl/− Wnt1-Cre mutants (Fig. 5C and D).

Table 1.

Mendelian ratios of offspring from matings of Nrp1fl/fl and Nrp1+/− Wnt1-Cre+ mice.

| Genotype | Total no. | Observed (%) | Expected (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nrp1fl/+ (no Cre) | 29 | 23.4 | 25 |

| Nrp1fl/− (no Cre) | 32 | 25.8 | 25 |

| Nrp1fl/+Wnt1-Cre+ | 34 | 27.4 | 25 |

| Nrp1fl/−Wnt1-Cre+ | 29 | 23.4 | 25 |

| Total no. | 124 | 100 | 100 |

Fig. 5.

Abnormal target organ innervation in mice lacking NRP1 in the NC lineage. (A–D) TH immunolabelling of sympathetic fibres on the ventricular surface of E17.5 hearts. (E and F) TH immunolabelling of 20 μm cryosections through the P7 ventricular wall reveals the sympathetic fibre distribution between epicardium (epi) and endocardium (endo); double-headed red arrows indicate the width of the subepicardial (1) and subendocardial (3) areas and the intervening myocardial area (2) quantified in (G). (H) Mean sympathetic fibre density in the subendocardium of the indicated genotypes, normalised to fibre density in the subepicardium of the same genotype (set to a value of 1, indicated with a dashed line; n=4). (I and J) 100 μm transverse vibratome sections through P7 aorta, double immunolabelled for TH (green) and alpha smooth muscle actin (SMA, red). (K) Quantification of sympathetic fibres in 20 μm transverse cryosections through P7 aorta; n=4. Error bars: s.e.m.; the asterisks indicate a P-value <0.05. Scale bars: A–D 500 μm; E,F 20 μm; I,J 100 μm.

Quantitation of TH-positive fibres in immunolabelled sections through postnatal day (P) 7 hearts confirmed that sympathetic innervation of the subepicardium was reduced in Nrp1fl/− Wnt1-Cre mutants compared to littermate controls (Fig. 5E and F; number of subepicardial TH-positive fibres per mm2: Nrp1fl/+ 1814±426 vs. Nrp1fl/− Wnt1-Cre 1086±206; mean±s.e.m.). By contrast, innervation of the subendocardium was increased in mutants compared to controls (Fig. 5E and F; number of subendocardial TH-positive fibres per mm2: Nrp1fl/+ 173±35 vs. Nrp1fl/− Wnt1-Cre 800±286; mean±s.e.m.). As a consequence, the epicardial-to-endocardial innervation gradient was lost in mice lacking NRP1 in the NC lineage (Fig. 5G).

The innervation defect manifested itself as a significant difference in the ratio of endocardial to epicardial fibres (Fig. 5H). Specifically, there were 0.15 sympathetic fibres in the subendocardium for each fibre in the subepicardium of wild-type hearts, but 0.69 fibres in the subendocardium for each fibre in the subepicardium of Nrp1fl/− Wnt1-Cre mutant hearts (Fig. 5H; P<0.05). However, the total number of sympathetic axons was similar in the ventricular wall of mutants and wild-type littermates (total number of TH-positive fibres: Nrp1fl/+ 83.4±20.5, n=5, vs. Nrp1fl/− Wnt1-Cre 80.2±9.3, n=8; mean±s.e.m.). SEMA3A signalling through NRP1 is therefore not essential for sympathetic projection to the heart, but regulates the intracardial distribution of sympathetic axons.

Sympathetic axons have been reported to innervate the smooth muscle layer of the canine abdominal aorta, where they may contribute to the systemic control of blood pressure (Gerova et al., 1973). Immunolabelling of transverse sections through the P7 aorta of wild-type mice for TH and alpha-smooth muscle actin (SMA) revealed that the murine aorta is also innervated by sympathetic axons (Fig. 5I) and that their number is significantly reduced in Nrp1fl/− Wnt1-Cre mutants (Fig. 5J and K; mean number of TH-positive fibres: wild-types 7.0±0.8 vs. mutants 3.6±0.5; mean±s.e.m.; n=4 each; P<0.05). Thus, despite premature axon extension towards the aorta at earlier developmental stages, sympathetic innervation of the aorta is compromised at postnatal stages in mutants lacking NC-derived NRP1. Mice lacking NRP1 in the NC lineage may therefore provide a useful experimental model to study the contribution of sympathetic aortic innervation to blood pressure regulation under physiological conditions.

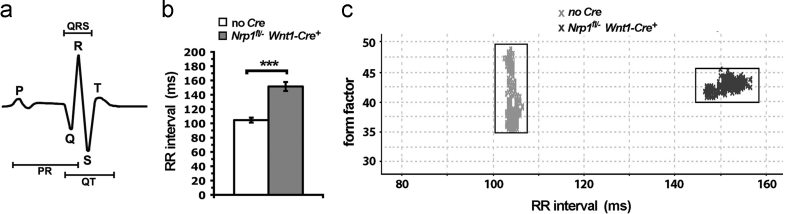

Sinus bradycardia in mice lacking NRP1 signalling in the sympathetic lineage

In vertebrates, the SNS innervates the heart to regulate its rate and force of contraction according to physiological demand. To investigate how abnormal sympathetic innervation affects heart rhythm, we performed electrocardiography (ECG) in anaesthetised adult Nrp1fl/− Wnt1-Cre mutants, which were viable (in contrast, Nrp2-null mutants fail to thrive after birth; (Yuan et al., 2002). In a normal mouse ECG, a single heart beat is resolved into: the P wave that originates from the pacemaker activity of the sinoatrial node and represents atrial depolarisation; the R wave that represents ventricular depolarisation; the PR interval that reflects the delay between atrial and ventricular depolarisation as signal spreads through the atrioventricular node and His-Purkinje system; the QRS complex that marks depolarisation of the ventricles; and the T wave that reflects repolarisation of the ventricles (Fig. 6A). We found that the ECG parameters for each individual heartbeat were similar between 4 Nrp1fl/− Wnt1-Cre mutants and 6 Nrp1fl/+ or Nrp1fl/− control littermates (for the controls, we pooled data from 2 Nrp1fl/+ and 4 Nrp1fl/− mice). For example, the average duration of the PR, QRS and QT intervals were similar for both groups (PR: Nrp1fl/− Wnt1-Cre 38.5±0.5 ms vs. controls 37.8±0.3 ms; QRS: Nrp1fl/− Wnt1-Cre, 9±0 ms vs. controls 9±0.1 ms; QT: Nrp1fl/− Wnt1-Cre 17.7±2 ms vs. control 19±9 ms; mean±s.e.m). This observation suggests that there are no gross structural abnormalities in the mutant heart.

Fig. 6.

Loss of NRP1-mediated SNS patterning leads to sinus bradycardia. (a) An idealised schematic representation of a mouse ECG trace; abbreviations: P, Q, R, S, T indicate the respective ECG waves; QRS, complex of the Q, R and S waves; QT or PR indicate intervals between the respective waves. (b) The RR interval, which is inversely related to heart rate, is significantly prolonged in Nrp1fl/−Wnt1-Cre mice compared to control Nrp1fl/+ and Nrp1fl/− littermates lacking Cre (*** indicates P<0.001). (c) Scatterplot of individual RR-intervals (crosses) in a 2-minute ECG recording from two representative littermate mice of Nrp1fl/− and Nrp1fl/−Wnt1-Cre genotypes; the squares indicate tight clustering of the values for each mouse. The form factor (Y axis) provides a measure of the consistency of QRS complex morphology; clustering around a specific RR-interval indicates a normal QRS complex.

Even though individual heartbeats appeared normal, the interval between two adjacent R waves was larger in the anaesthetised mutants compared to controls (Nrp1fl/− Wnt1-Cre 151.5±6 ms vs. controls 104.5±4 ms; mean±s.e.m). This difference in RR interval was highly significant (P<000.1) and translated to a reduction in heart rate from 574 beats per minute (bpm) in controls to only 396 bpm in the mutants (Fig. 6B). A scatterplot of individual RR-intervals in a 2-min ECG recording from a representative pair of Nrp1fl/− and Nrp1fl/− Wnt1-Cre littermates showed tight clustering of RR values for each mouse, indicating that bradycardia was persistent, but with normal QRS complex morphology (Fig. 6C). Together with similar findings in Sema3a-null mutants (Ieda et al., 2007), these observations demonstrate that SEMA3A/NRP1-regulated cardiac sympathetic innervation is important for a stable heart rhythm in mice.

Conclusions and future directions

We have shown here that NRP1 conveys SEMA3A signals cell-autonomously in the sympathetic lineage to facilitate normal SNS function in adults, and that this pathway synergises with SEMA3F/NRP2 signalling to control sympathetic neuronal development. Given the inability of neuropilins to convey class 3 semaphorin signals without a co-receptor (Nakamura et al., 1998) and phenotypic similarities of mutants lacking semaphorin signalling through both NRP1 and NRP2 and mutants lacking both PLXNA3 and PLXNA4 (Waimey et al., 2008), it is likely that these two plexins transduce SEMA3A/3F signals during secondary sympathetic neuron migration and axon guidance in the SNS. Consistent with this idea, the alternative neuropilin co-receptor VEGFR1 (also known as FLK1 or KDR) was not expressed at detectable levels in sympathetic neurons by immunostaining (K. D. and C. R., unpublished observation). In addition to defects in secondary sympathetic neuron migration and neurite extension, mutants lacking SEMA3A or NRP1 also contain scattered ectopic neurons in the periphery due to defective NC guidance. As PLXNA3 and PLXNA4 were reported to not be expressed during sympathetic NC migration and lack such scattered neurons (Waimey et al., 2008), the neuropilin co-receptors in sympathetic NC cells remain to be identified. Possible candidates include PLXNA1 and PLXNA2, as both bind NRP1 and convey SEMA3A signals in vitro (Rohm et al., 2000; Takahashi et al., 1999). Finally, the observation that the sympathetic chains still assemble in the absence of semaphorin signalling through NRP1 and NRP2 suggests that additional signalling pathways remain to be identified that synergise with NRP1 and NRP2 to guide SNS patterning.

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff of the Biological Resources Unit for mouse husbandry and the Imaging Facility of the UCL Institute of Ophthalmology for help with confocal microscopy. We are grateful to Laura Denti for help with genotyping, Alessandro Fantin for technical advice and helpful discussions and Matthew Golding for critical reading of the manuscript. This study was supported by a doctoral training account from the UK Medical Research Council (MRC) to C.M. (G070020), a project grant from the UK Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) to C.R. (BB/I008373/1), a programme grant from the UK British Heart Foundation to A. T. (RG/10/10/28447) and a training fellowship from the UK British Heart Foundation to J.G. (FS/07/031).

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.06.026.

Appendix A. Supplementary materials

Supplementary material

References

- Bronner-Fraser M. Analysis of the early stages of trunk neural crest migration in avian embryos using monoclonal antibody HNK-1. Dev. Biol. 1986;115:44–55. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(86)90226-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cariboni A., Davidson K., Rakic S., Maggi R., Parnavelas J.G., Ruhrberg C. Defective gonadotropin-releasing hormone neuron migration in mice lacking SEMA3A signalling through NRP1 and NRP2: implications for the aetiology of hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Hum Mol. Genet. 2011;20:336–344. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cau E., Gradwohl G., Fode C., Guillemot F. Mash1 activates a cascade of bHLH regulators in olfactory neuron progenitors. Development. 1997;124:1611–1621. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.8.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., He Z., Bagri A., Tessier-Lavigne M. Semaphorin-neuropilin interactions underlying sympathetic axon responses to class III semaphorins. Neuron. 1998;21:1283–1290. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80648-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson C.A., Duong T.D., Tosney K.W. Descriptive and experimental analysis of the dispersion of neural crest cells along the dorsolateral path and their entry into ectoderm in the chick embryo. Dev. Biol. 1992;151:251–272. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(92)90231-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gammill L.S., Gonzalez C., Gu C., Bronner-Fraser M. Guidance of trunk neural crest migration requires neuropilin 2/semaphorin 3F signaling. Development. 2006;133:99–106. doi: 10.1242/dev.02187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerova M., Gero J., Dolezel S., Blazkova-Huzulakova I. Sympathetic control of canine abdominal aorta. Circ. Res. 1973;33:149–159. doi: 10.1161/01.res.33.2.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giger R.J., Cloutier J.F., Sahay A., Prinjha R.K., Levengood D.V., Moore S.E., Pickering S., Simmons D., Rastan S., Walsh F.S., Kolodkin A.L., Ginty D.D., Geppert M. Neuropilin-2 is required in vivo for selective axon guidance responses to secreted semaphorins. Neuron. 2000;25:29–41. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80869-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giger R.J., Urquhart E.R., Gillespie S.K., Levengood D.V., Ginty D.D., Kolodkin A.L. Neuropilin-2 is a receptor for semaphorin IV: insight into the structural basis of receptor function and specificity. Neuron. 1998;21:1079–1092. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80625-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu C., Rodriguez E.R., Reimert D.V., Shu T., Fritzsch B., Richards L.J., Kolodkin A.L., Ginty D.D. Neuropilin-1 conveys semaphorin and VEGF signaling during neural and cardiovascular development. Dev. Cell. 2003;5:45–57. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00169-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ieda M., Kanazawa H., Kimura K., Hattori F., Ieda Y., Taniguchi M., Lee J.K., Matsumura K., Tomita Y., Miyoshi S., Shimoda K., Makino S., Sano M., Kodama I., Ogawa S., Fukuda K. Sema3a maintains normal heart rhythm through sympathetic innervation patterning. Nat. Med. 2007;13:604–612. doi: 10.1038/nm1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X., Rowitch D.H., Soriano P., McMahon A.P., Sucov H.M. Fate of the mammalian cardiac neural crest. Development. 2000;127:1607–1616. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.8.1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones E.A., Yuan L., Breant C., Watts R.J., Eichmann A. Separating genetic and hemodynamic defects in neuropilin 1 knockout embryos. Development. 2008;135:2479–2488. doi: 10.1242/dev.014902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagoshima M., Ito T. Diverse gene expression and function of semaphorins in developing lung: positive and negative regulatory roles of semaphorins in lung branching morphogenesis. Genes Cells. 2001;6:559–571. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2001.00441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasemeier-Kulesa J.C., Kulesa P.M., Lefcort F. Imaging neural crest cell dynamics during formation of dorsal root ganglia and sympathetic ganglia. Development. 2005;132:235–245. doi: 10.1242/dev.01553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki T., Bekku Y., Suto F., Kitsukawa T., Taniguchi M., Nagatsu I., Nagatsu T., Itoh K., Yagi T., Fujisawa H. Requirement of neuropilin 1-mediated Sema3A signals in patterning of the sympathetic nervous system. Development. 2002;129:671–680. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.3.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby M.L., Gilmore S.A. A correlative histofluorescence and light microscopic study of the formation of the sympathetic trunks in chick embryos. Anat. Rec. 1976;186:437–449. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091860309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisanuki Y.Y., Hammer R.E., Miyazaki J., Williams S.C., Richardson J.A., Yanagisawa M. Tie2-Cre transgenic mice: a new model for endothelial cell-lineage analysis in vivo. Dev. Biol. 2001;230:230–242. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.0106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitsukawa T., Shimizu M., Sanbo M., Hirata T., Taniguchi M., Bekku Y., Yagi T., Fujisawa H. Neuropilin-semaphorin III/D-mediated chemorepulsive signals play a crucial role in peripheral nerve projection in mice. Neuron. 1997;19:995–1005. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80392-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Douarin N.M., Kalcheim C. second ed. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1999. The Neural Crest. [Google Scholar]

- Loring J.F., Erickson C.A. Neural crest cell migratory pathways in the trunk of the chick embryo. Dev. Biol. 1987;121:220–236. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(87)90154-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marko S.B., Damon D.H. VEGF promotes vascular sympathetic innervation. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2008;294:H2646–H2652. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00291.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura F., Tanaka M., Takahashi T., Kalb R.G., Strittmatter S.M. Neuropilin-1 extracellular domains mediate semaphorin D/III-induced growth cone collapse. Neuron. 1998;21:1093–1100. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80626-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickmann M., Fawcett J.W., Keynes R.J. The migration of neural crest cells and the growth of motor axons through the rostral half of the chick somite. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol. 1985;90:437–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roffers-Agarwal J., Gammill L.S. Neuropilin receptors guide distinct phases of sensory and motor neuronal segmentation. Development. 2009;136:1879–1888. doi: 10.1242/dev.032920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohm B., Ottemeyer A., Lohrum M., Puschel A.W. Plexin/neuropilin complexes mediate repulsion by the axonal guidance signal semaphorin 3A. Mech. Dev. 2000;93:95–104. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(00)00269-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruhrberg C., Gerhardt H., Golding M., Watson R., Ioannidou S., Fujisawa H., Betsholtz C., Shima D.T. Spatially restricted patterning cues provided by heparin-binding VEGF-A control blood vessel branching morphogenesis. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2684–2698. doi: 10.1101/gad.242002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruhrberg C., Schwarz Q. In the beginning: generating neural crest cell diversity. Cell Adh. Migr. 2010:4. doi: 10.4161/cam.4.4.13502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahay A., Molliver M.E., Ginty D.D., Kolodkin A.L. Semaphorin 3F is critical for development of limbic system circuitry and is required in neurons for selective CNS axon guidance events. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:6671–6680. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-17-06671.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz Q., Maden C.H., Davidson K., Ruhrberg C. Neuropilin-mediated neural crest cell guidance is essential to organise sensory neurons into segmented dorsal root ganglia. Development. 2009;136:1785–1789. doi: 10.1242/dev.034322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz Q., Maden C.H., Vieira J.M., Ruhrberg C. Neuropilin 1 signaling guides neural crest cells to coordinate pathway choice with cell specification. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009;106:6164–6169. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811521106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz Q., Vieira J.M., Howard B., Eickholt B.J., Ruhrberg C. Neuropilin 1 and 2 control cranial gangliogenesis and axon guidance through neural crest cells. Development. 2008;135:1605–1613. doi: 10.1242/dev.015412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz Q., Waimey K.E., Golding M., Takamatsu H., Kumanogoh A., Fujisawa H., Cheng H.J., Ruhrberg C. Plexin A3 and plexin A4 convey semaphorin signals during facial nerve development. Dev. Biol. 2008;324:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T., Fournier A., Nakamura F., Wang L.H., Murakami Y., Kalb R.G., Fujisawa H., Strittmatter S.M. Plexin-neuropilin-1 complexes form functional semaphorin-3A receptors. Cell. 1999;99:59–69. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80062-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takashima S., Kitakaze M., Asakura M., Asanuma H., Sanada S., Tashiro F., Niwa H., Miyazaki Ji J., Hirota S., Kitamura Y., Kitsukawa T., Fujisawa H., Klagsbrun M., Hori M. Targeting of both mouse neuropilin-1 and neuropilin-2 genes severely impairs developmental yolk sac and embryonic angiogenesis. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002;99:3657–3662. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022017899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi M., Yuasa S., Fujisawa H., Naruse I., Saga S., Mishina M., Yagi T. Disruption of semaphorin III/D gene causes severe abnormality in peripheral nerve projection. Neuron. 1997;19:519–530. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80368-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voyvodic J.T. Development and regulation of dendrites in the rat superior cervical ganglion. J. Neurosci. 1987;7:904–912. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-03-00904.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waimey K.E., Huang P.H., Chen M., Cheng H.J. Plexin-A3 and plexin-A4 restrict the migration of sympathetic neurons but not their neural crest precursors. Dev. Biol. 2008;315:448–458. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip J.W. Migratory patterns of sympathetic ganglioblasts and other neural crest derivatives in chick embryos. J. Neurosci. 1986;6:3465–3473. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.06-12-03465.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip J.W. Specific innervation of neurons in the paravertebral sympathetic ganglia of the chick. J. Neurosci. 1986;6:3459–3464. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.06-12-03459.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan L., Moyon D., Pardanaud L., Breant C., Karkkainen M.J., Alitalo K., Eichmann A. Abnormal lymphatic vessel development in neuropilin 2 mutant mice. Development. 2002;129:4797–4806. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.20.4797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material