Abstract

Objectives

Intimate partner violence (IPV), commonly known as domestic violence is a problem throughout the world. An estimated 36% to 75% of employed abused woman are monitored, harassed and physically assaulted by their partners or ex-partners while trying to get to work and while at work. The objective of this research is to evaluate the effectiveness of interactive training to increase knowledge, change perceptions and develop an intention to address domestic violence that spills over into the workplace.

Methods

Community-based participatory research approaches were employed to develop and evaluate an interactive computer-based training (CBT) intervention, aimed to teach supervisors how to create supportive and safe workplaces for victims of IPV.

Results

The CBT intervention was administered to 53 supervisors. All participants reacted positively to the training, and there was a significant improvement in knowledge between pre- and post-training test performance (72% versus 96% correct), effect size (d) = 3.56. Feedback from focus groups was more productive than written feedback solicited from the same participants at the end of the training.

Conclusion

Effective training on the impacts of IPV can improve knowledge, achieving a large effect size, and produce changes in perspective about domestic violence and motivation to address domestic violence in the workplace, based on questionnaire responses.

Keywords: Domestic violence, Workplace, Occupational, Training, Intervention

Introduction

Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) is well established as a wide-spread problem with important negative health, social and cost consequences for the victims, perpetrators, the workplace and community. IPV commonly known as domestic violence is defined as threatened, attempted, or completed physical or sexual violence or emotional abuse by a current or former intimate partner [1-3]. Population-based self report surveys administered in 50 countries document that IPV is perpetrated against women from every populated continent. Between 3% and 5% of women report experiencing physical violence within a year before the survey, the variability due to differing definitions of violence and presumably cultural differences [4]. IPV is more extensively studied in developed countries. For example in the US, each year, IPV results in an estimated 1,200 deaths and 2 million injuries, and costs an estimated $5.8 billion [3]. This includes nearly $900 million in lost productivity [3]. From the National 2005 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) survey, 23.6% of women reported a lifetime history of IPV [1]. Reporting of health conditions and risk behaviors are significantly higher among women who experience IPV during their lifetimes compared with women who never experience [5-7]. While an estimated 2.9 million intimate partner assaults are committed against men each year, women's rates of injury (41.6% vs. 20%) are far greater [8].

Domestic violence and the workplace

Researchers, health care providers, domestic violence advocates, employers, and unions find that the spillover of IPV into the workplace affects the productivity, absenteeism, safety and well-being of all employees [9-12]. Studies of abused working women indicated that between 40% and 87% experienced stalking at their workplace by their abusers [8,13-15]. More women die because they are murdered on the job than die from any other cause at work, with 17% of these murders committed by a current or former intimate partner [16,17]. The workplace may be the one location that the abuser knows he can find his estranged partner after she has left the violent relationship. Because women are disproportionately the victims of IPV and have more severe outcomes, we developed an intervention, Domestic Violence and the Workplace, to focus on female workers as the victims of domestic violence.

States have searched for ways to protect IPV victims, who are often threatened with job loss when they seek time off to access services and resources to increase their safety. Increasingly, domestic violence advocates, policymakers and legal experts are working closely with businesses to increase their role in the coordinated community response to preventing IPV, including State laws to provide employment protection to victims of IPV. Since these laws are often not well known by employees, training interventions are needed to bring the seriousness of IPV and the importance of State laws and local domestic violence services to the attention of work supervisors and managers.

Computer-based training intervention

Workplace interventions typically employ training as the primary tool. Burke et al. [18] compared the effectiveness of different types of workplace interventions published in peer-reviewed literature between 1971 and 2003. Of the 95 studies that met the criteria of their meta-analysis, a mean effect size of 0.54 was seen for knowledge change for the less engaging methods such as videos, 0.79 for the moderately engaging methods such as interactive computer-based training, and 1.89 for the highly engaging methods such as in-person lectures with question-and-answer participation. Although, the highly engaging approaches are likely more effective in changing knowledge, they are not cost-effective approaches especially in smaller businesses. We therefore selected an interactive computer-based training (CBT) approach for the Domestic Violence and the Workplace intervention with small service organizations in Oregon.

Purpose of the study

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the acceptability and effectiveness of computer-based training in teaching the basic principles of responding to problems of intimate personal violence that spill over to the workplace and obtain feedback from supervisors. In prior training research [17,19], research staff met individually with pilot participants to obtain feedback on training programs. Alternatives to this time-consuming and thus expensive process were examined in the present study. In addition to measuring participant reaction and knowledge gained from Domestic Violence and the Workplace, the feedback from participant's written comments was compared to those of focus groups for identifying improvements needed in the CBT to prepare for the larger statewide training implementation. The intervention was developed for organizations in the state of Oregon in the US.

Materials and Methods

Assessment phase: development of the training content

The study team, community advisors, and community partners conducted focus groups and surveys to gain information on effective workplace intervention strategies from the perspectives of abused women, male abusers, workers, and supervisors sampled in the state of Oregon (US). The findings from surveys with abused women (n = 281) indicated that employed victims of IPV are vulnerable to violence in the workplace by an abusive partner or ex-partner. The abusive behaviors of their partners interfere with their ability to do their work, stay at work and keep their job. Additionally, the abusers report that their behavior impacts their own work performance and work productivity. Male abusers (n = 197) reported that they used workplace resources (e.g. phone, email, company cars and coworkers) to monitor and harass their partner or ex-partner at her workplace. They also reported experiencing support for enrollment in batterers treatment and time off from work for court dates from their supervisors, where victims reported that they are "a dime a dozen" and will be replaced if they "bring their problems to work" or challenge unsafe work conditions. Women reported limited/no access to information on domestic violence resources or support from supervisors for when they experience IPV or challenge potentially dangerous workplace policies (e.g., locked doors, no access to telephone, and late night shifts). Further, we conducted focus groups with workers and supervisors to develop strategies to provide IPV training and resources to supervisors [20-24]. We have used the findings from this assessment phase of the project to develop the Domestic Violence and the Workplace intervention with scenarios to provide information, support and resources to supervisors in order to improve their response to IPV victims and abusers as well as their co-workers.

The key findings from the assessment phase that were included in the intervention, are: 1) the broad (health, safety, employment) impact of IPV across population sectors (7 screens of training were devoted to this topic); 2) the multiple strategies abusers use to dominate and control their victims including examples of physical, sexual, emotional abuse and stalking (8 screens); 3) why abused victims stay in the relationship (1 screen); 4) examples of the impact of IPV on victims and abusers productivity, absenteeism and performance, such as over 50% of abusers and abused victims have missed or were unable to perform their work at times (6 screens); 5) costs to Oregon businesses have been estimated at $50 million per year, including health care costs and lost productivity (1 screen); 6) reports by victims of IPV of the type of support they want from supervisors/coworkers (7 screens); 7) steps supervisors can take to support victims and hold abusers accountable for behavior (13 screens); 8) employment law, with a specific focus on Oregon's 2007 protected leave law for victims of domestic violence, sexual assault and stalking (9 screens); 9) need for workplace domestic violence policy (content of the policy) and a sample template of a model workplace policy (6 screens); 10) community resources to assist supervisors (1 screen).

The training content we developed consisted of 56 "screens" of information, each with 1 or more pictures depicting the information. Interspersed in the training screens were 13 brief movie clips of background on the research study, stories of IPV and the impact on employment, available resources including domestic violence service providers, police and legal advocacy, and the Oregon law regarding employer responsibilities, such as protected leave. The 56 screens were divided into 10 "information set" groupings with 1-3 quiz questions of the total 17 quiz questions were presented at the end of each of the information sets.

Intervention phase: evaluation of the training intervention

The training was presented in cTRAIN [25], a computer-based training (CBT) program that was selected because it has: 1) Format based on effective behavioral education principles (e.g., self-pacing, frequent quizzes, interactive feedback, high accuracy criterion); 2) Clear system training instructions, so participants do not require coaching on how to use the program; 3) Icon-based navigation cues always on-screen, so there are no commands to remember; 4) Ready implementation of pictures and a movie on all screens. A pre-test, quiz questions in the training, and a post-test asked the same questions and had the same multiple choice answers, but each questions' answers were in a different order in the pre-test, training quiz questions and the post-test.

Procedures

The training was administered in a large open room with tables for up to 20 computer locations or in smaller conference rooms, overseen by 2-4 project staff (Fig. 1). Participants were given an OHSU IRB-approved consent form to sign and a demographic questionnaire, which sought information about background and occupational history and the degree to which participants had encountered IPV or the impact of IPV at their workplace. An evaluation questionnaire was given to participants at the end of the training, and participants were asked to enter written comments in the evaluation questionnaire and to participate in a subsequent focus group meeting. Focus Groups were conducted at the completion of the CBT in an available office or conference room adjacent to the training room. The questions on the evaluation questionnaire and in the focus groups related to the acceptability of the training format (e.g., was it easy to use, easy to understand) and the value of the content (e.g., did they learn from the training, were they motivated to make changes at their workplace). There were three openended questions: 1) Any comments; 2) How can the training be improved; 3) Further comments. Because training was started when people arrived in the testing room and because of the self-paced training, participants arrived in the focus groups at different times. Thus, up to four focus groups were run in each setting, and the size of the group was between 1 and 15 at any time. Pre-planned questions were asked of a sample of participants, but we did not attempt to ensure that all participants heard all questions.

Fig. 1.

Test room for participants from the City.

Results

Participants

Fifty-three participants (27 male, 26 female) completed the training in community locations from two occupational settings: 1) City - Gresham, Oregon (4th largest city in Oregon) city police & other city employees (n=31); and 2) Small Businesses - front line and upper level supervisors at a medium-sized bank in Gresham and the owner of a small insurance company (n = 22). Ten from Gresham city were active police force members according to their job titles. Based on employee records, the number of employees of the city was 461 and the bank had an estimated 70 employees; the insurance company had an estimated 50 employees based on observation at the time of the study. The mean age of the 53 participants was 46.0 years (range 25-62 years). Two were Asian, one was Native American and 50 were Caucasian. Three participants identified as Latino. Seven had high school diplomas, one had a GED following 11 years of school and the other 45 had completed one or more years of college. All but two participants (who did not complete the questions) indicated they spent in excess of 5 hours per week using a computer though only 3 indicated they spent more than 12 hours a week surfing the internet. Most participants identified as middle management/supervisor (64%) or owner/upper management (25%), followed by line worker/staff (8%); all identified as full-time employees. Of the 53, 20.8% identified as a member of a union, and 84.9% indicated they were supervisors who supervised between 1 and 106 employees.

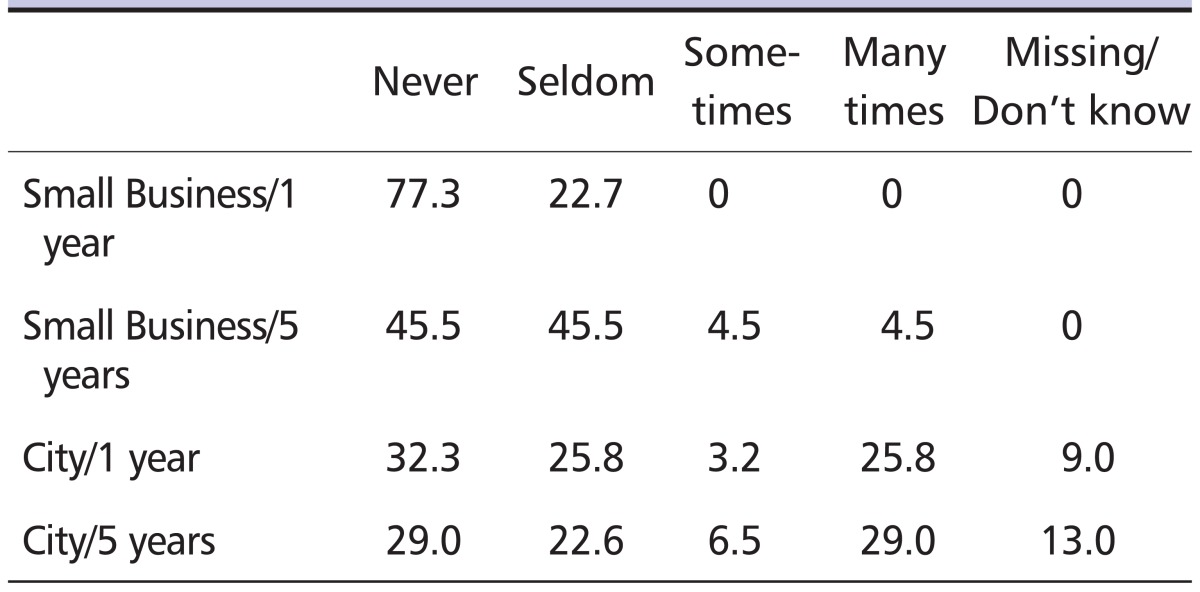

Participants' exposure to domestic violence issues at work

Just over half (50.9%) of participants reported that they had not encountered issues related to domestic violence at their work in the past year, but that percentage declined to 35.9% when the timeframe was extended to the last 5 years. Conversely, 15.1% reported encountering domestic violence in the workplace "many times" in the past year, and the percentage of such encounters rose to 18.9% for the longer time frame of the past 5 years. The City supervisors had a higher frequency of encountering workplace domestic violence than the Small Business supervisors, as seen in Table 1. However, 4.5% of the Small Business supervisors had encountered domestic violence in the workplace "many times" in the past 5 years and more than half (54.5%) of the small business supervisors had some contact (i.e. seldom, sometimes, many times) with domestic violence at their workplace in the past 5 years (Table 1).

Table 1.

Percentage of small business and city managers who reported encountering issues related to domestic violence at work at 1 and 5 years

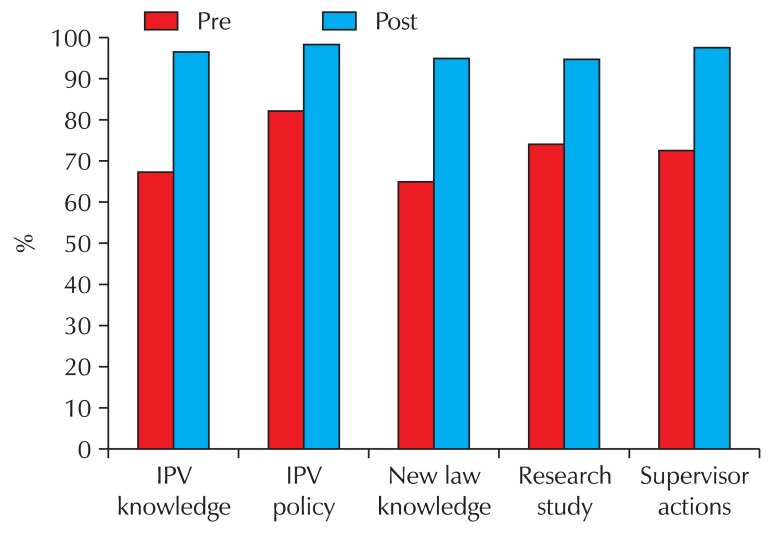

Knowledge

Prior to using the training, the mean percent correct on the knowledge of domestic violence and the workplace test was 71.8 (sd = 0.130). After completing the training, the mean percent correct rose to 96.1 (sd = 0.132) on the knowledge post-test. It took a mean of 11.9 min to complete the pre-test and 3.9 min to complete the post-test; it is typical for people to contemplate their answers to the pre-test but work quickly through the post-test when they know the answers. A two-way ANOVA with time (pre versus post) and group (City versus small business) as the independent variables and percent correct on the knowledge test as the dependent variable revealed that the improvement in knowledge from pre to post intervention was significant, p < 0.001, effect size (d) = 3.56. The intervention was equally effective for City and small businesses (group by time interaction, p = 0.401).

Test results also indicated a consistent level of pre-training knowledge about domestic violence in the workplace across 5 main topics of the training and consistently high knowledge after the training, as seen in Fig. 1. Paired t-tests found that supervisor's knowledge improved significantly in all five areas of training; IPV knowledge (p < 0.001, effect size = 2.29), IPV policy (p < 0.001, effect size = 0.63), new law (p < 0.001, effect size = 1.30), research study (p < 0.001, effect size = 1.12), and supervisor actions (p < 0.001, effect size = 1.12). The City supervisors knew slightly more about Oregon's protected leave law (70% vs. 60%) than the Small Business supervisors, reaching statistical significance by a t-test (p = 0.02) at pre-test. The differences disappeared at the post-test.

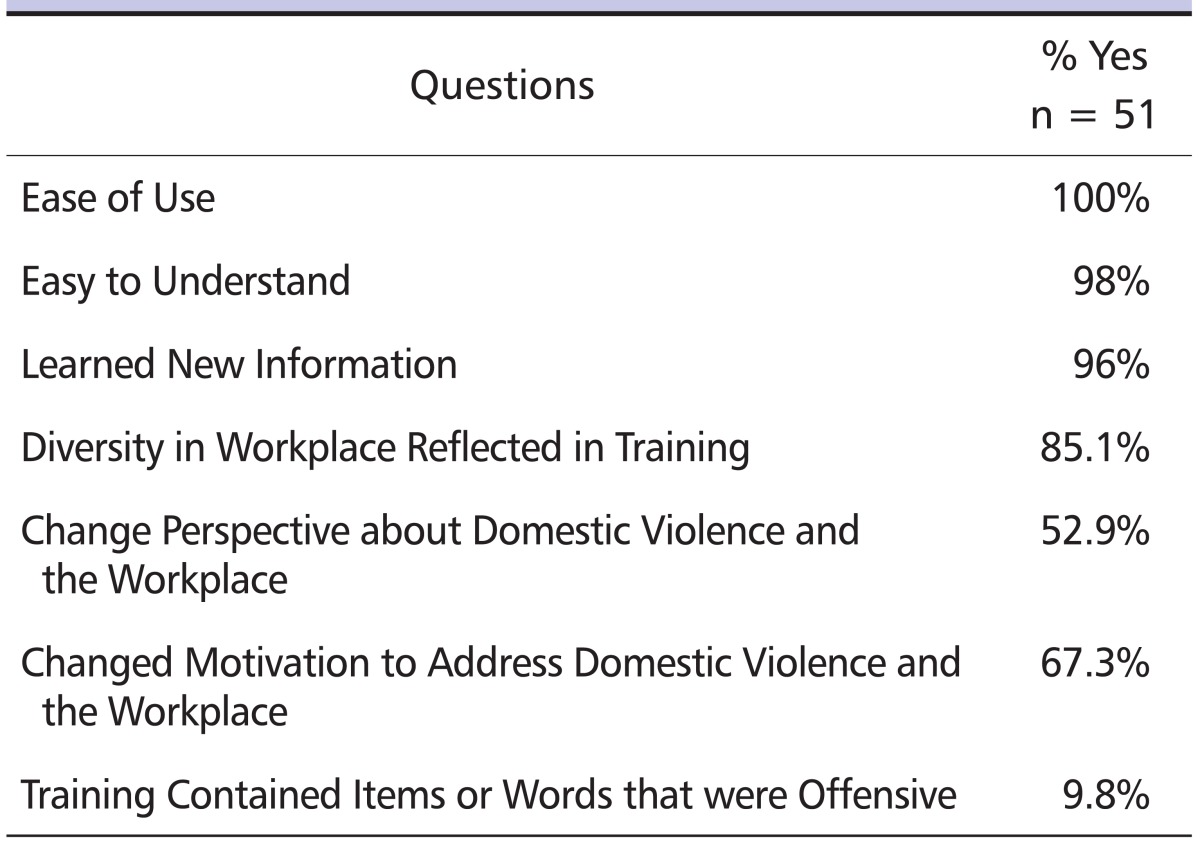

Objective training evaluation form: Yes-No questions

Responses on the objective evaluation questionnaire were obtained from 51 (96%) of participants (Table 2). Tabulations indicated that 100% of respondents found the "computerized training was easy to use" and 98% found the language "easy to understand," indicating that the training format and text facilitated learning the material. All but two participants (96%) indicated that they had learned new information from the training. Participants also found that the training reflected diversity in the workplace (85.1%), and 5 participants (9.8%) reported that the training contained items or words that were offensive. Two key questions addressed the impact of the information on participant thinking. Just over half the participants (52.9%) indicated that the training "changed their perspective about domestic violence and the workplace" and 67.3% indicated that the training "changed my motivation to address domestic violence in the workplace."

Table 2.

Training evaluation

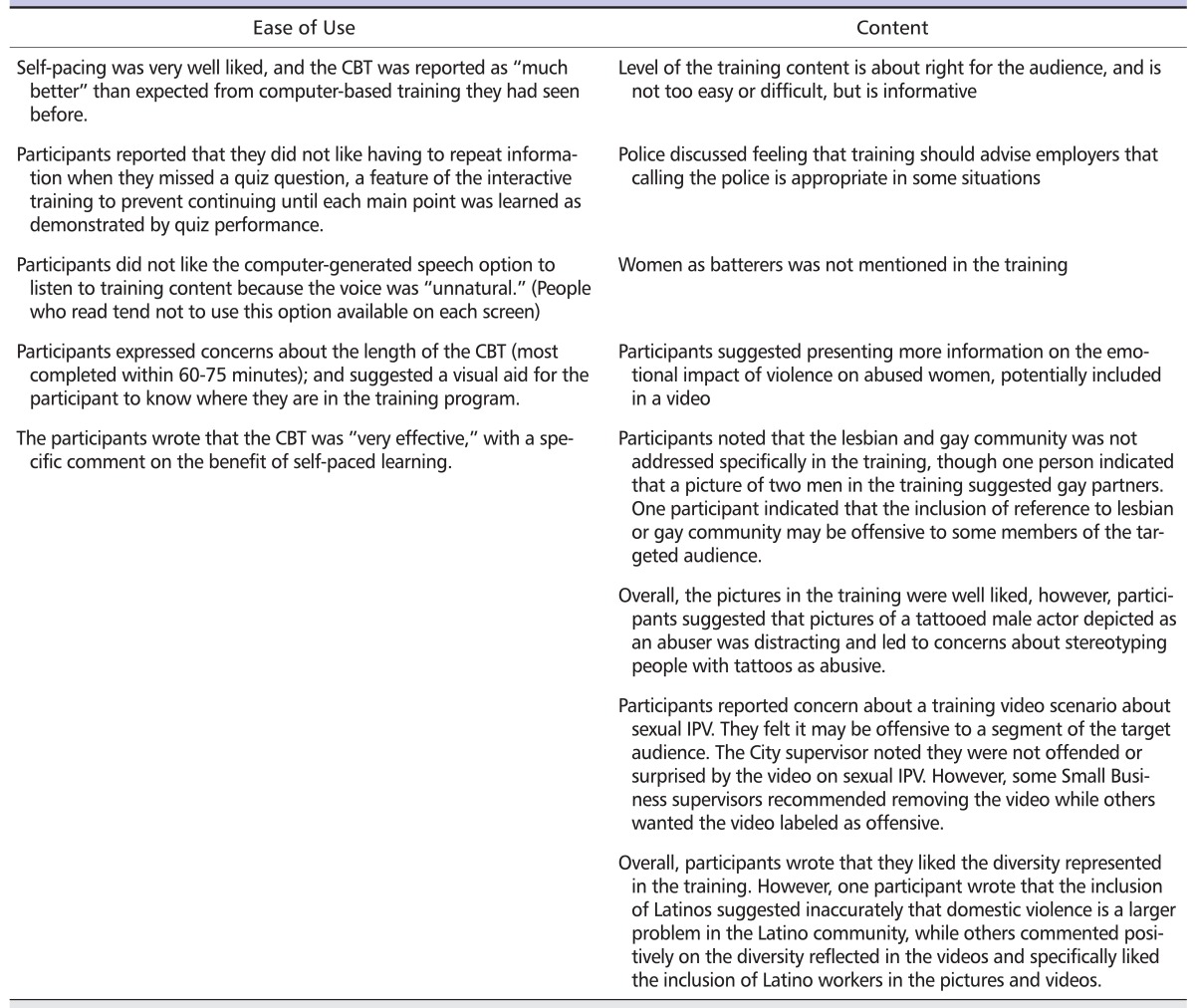

Objective training evaluation form: open-ended questions

The open-ended questions allowed the participants to enter comments without focusing their responses on specific issues considered important by the investigators. They are summarized on "ease of use" and "content" in Table 3.

Table 3.

Training evaluation: focus group and written comments

CBT: computer-based training, IPV: intimate partner violence.

Discussion and Conclusions

The 53 participants in this study reported exposure to IPV at the workplace, from the City supervisors (71% in the last 5 years) and in the Small Business participants (54.5% in the last 5 years). Prior to presenting the training intervention, the mean percent correct on the knowledge of IPV and the workplace test was 71.8 (sd = 0.130). After completing the training, the mean percent correct rose to 96.1 (sd = 0.132) on the knowledge post-test. An ANOVA revealed that this improvement was significant (p < 0.001), the effect size was 3.56, which is large (over 0.80) according to Cohen [26]. The Burke et al. [18] meta-analysis reported, for learning safety knowledge, an effect size of d = 0.55 for the least-engaging (e.g., booklet) methods, d = 0.74 for the moderately engaging (e.g., interactive computer-based training, such as used here) methods and d = 1.46 for the highly engaging methods (e.g., interactive lecture and discussion). The effect size in the present study of d = 3.56 is well above the mean of the most engaging methods and in fact this d was exceeded by only two of the studies reviewed by Burke and colleagues (2006). This indicates that the training in this study was highly effective in conveying information as measured by the post-test/pre-test improvement. The training changed the perspective of slightly more than half (52.9%) of participants about domestic violence and the workplace and increased motivation of the majority (67.3%) to address domestic violence by implementing some of the action options they learned from the training in their workplace. Thus, the training not only imparted knowledge effectively, that knowledge also led a majority of participants to at least verbally assert that they would take action to implement the training recommendations.

Both the written and focus group methods of obtaining feedback from supervisors completing the computer-based training (CBT) proved useful in identifying elements of the training that participants found incorrect, irrelevant, inappropriate or even offensive. However, the focus groups proved critical information for identifying which changes in the training were most important. Specifically, comments in the focus groups indicated that one video that identified an example of sexual IPV could potentially offend the targeted audience, work supervisors. Another important comment that was brought out in the focus groups was that the police participants considered the training to have an "anti-police" theme because we focused supervisors on working closely with the victim and trained domestic violence advocates to access support and resources. The police concerns were elicited from them by probing questions in the focus groups, as that opinion did not surface in written comments about the training but rather when the focus group facilitator queried the focus group participants. The focus groups discussion and probing of statements thus resulted in identifying additional issues for revisions, such as removing potential stereotypical images of abusers and anti-police references. Perhaps most telling, the focus groups revealed to the research staff the relative importance of the various comments made by participants. This was seen when some concerns were agreed to or expanded on by other participants of the focus group, and other comments were not followed by words but by body positions suggesting agreement (e.g., nodding 'yes'). This led to identifying specific text and pictures to revise for future large-scale interventions that we might not otherwise have identified for change due to a lack of multiple written comments. This effective use of focus groups suggests an efficient alternative to the more time-intensive process of one-on-one feedback sessions with participants that we had employed in past research or simply asking participants to provide written feedback on the training [17,19,27] and one that should be subjected to a systematic evaluation in future research.

Fig. 2.

Pre- and Post-training knowledge (percent correct) on the 5 main test topics regarding domestic violence and the workplace. IPV: intimate partner violence.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of the members of the community advisory committee and their organizations: Rebecca Hernandez, PhD, Hacienda CDC; Noelia Hernandez-Valdovinos, BS, Multnomah County Human Services; Kris Billhardt, Volunteers of America Home Free Program; Nanette Yragui, MS, Portland State University; Eric Mankowski, PhD, Portland State University; Gino Galvez, BS, Portland State University; Michael McGlade, PhD, Western Oregon University; Chiquita Rollins, PhD, Multnomah County Human Services; Maria Elena Ruiz, PhD, RN, Oregon Health & Science University. This project was funded by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Nursing Research (R01 NR008771). This report does not necessarily reflect the policies or views of the NIH or the National Institute of Nursing Research. The research protocol, training and consent forms were approved by the Institutional Review Boards (IRB) at Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU) and Johns Hopkins University.

Footnotes

Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU) and Dr Anger have a significant financial interest in Northwest Education Training and Assessment, LLC, a company that may have a commercial interest in the results of this research and technology. This potential conflict was reviewed and a management plan approved by the OHSU Conflict of Interest in Research Committee was implemented.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Adverse health conditions and health risk behaviors associated with intimate partner violence--United States, 2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57:113–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saltzman LE, Fanslow JL, McMahon PM, Shelley GA. Intimate partner violence surveillance: uniform definitions and recommended data elements. Atlanta (GA): National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 3.What is the burden of intimate partner violence in the United States? [Internet] Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2004. [cited 2007 Sep 18]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/omhd/Highlights/2004/HOct04.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Watts C, Zimmerman C. Violence against women: global scope and magnitude. Lancet. 2002;359:1232–1237. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08221-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glass N, Perrin N, Campbell JC, Soeken K. The protective role of tangible support on post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in urban women survivors of violence. Res Nurs Health. 2007;30:558–568. doi: 10.1002/nur.20207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell JC, Lewandowski LA. Mental and physical health effects of intimate partner violence on women and children. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1997;20:353–374. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70317-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell J, Jones AS, Dienemann J, Kub J, Schollenberger J, O'Campo P, Gielen AC, Wynne C. Intimate partner violence and physical health consequences. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1157–1163. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.10.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Prevalence, incidence, and consequences of violence against women: findings from the national violence against women survey. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice; 1998. p. 16. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Riger S, Raja S, Camacho J. The radiating impact of intimate partner violence. J Interpers Violence. 2002;17:184–205. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Riger S. Working together: challenges in collaborative research on violence against women. Violence Against Women. 1999;5:1099–1117. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Riger S, Ahrens C, Blickenstaff A. Measuring interference with employment and education reported by women with abusive partners: preliminary data. Violence Vict. 2000;15:161–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rothman EF, Hathaway J, Stidsen A, de Vries HF. How employment helps female victims of intimate partner violence: a qualitative study. J Occup Health Psychol. 2007;12:136–143. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.12.2.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cole LL, Grubb PL, Sauter SL, Swanson NG, Lawless P. Psychosocial correlates of harassment, threats and fear of violence in the workplace. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1997;23:450–457. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McFarlane J, Malecha A, Gist J, Schultz P, Willson P, Fredland N. Indicators of intimate partner violence in women's employment: implications for workplace action. AAOHN J. 2000;48:215–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tjaden PG, Thoennes N. Coworker violence and gender. Findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20:85–89. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00279-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moracco KE, Runyan CW, Loomis DP, Wolf SH, Napp D, Butts JD. Killed on the clock: a population-based study of workplace homicide, 1977-1991. Am J Ind Med. 2000;37:629–636. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0274(200006)37:6<629::aid-ajim7>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anger WK, Stupfel J, Ammerman T, Tamulinas A, Bodner T, Rohlman DS. The suitability of computer-based training for workers with limited formal education: a case study from the US agricultural sector. Int J Train Dev. 2006;10:269–284. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burke MJ, Sarpy SA, Smith-Crowe K, Chan-Serafin S, Salvador RO, Islam G. Relative effectiveness of worker safety and health training methods. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:315–324. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.059840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eckerman DA, Abrahamson K, Ammerman T, Fercho H, Rohlman DS, Anger WK. Computer-based training for food services workers at a hospital. J Safety Res. 2004;35:317–327. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2003.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glass N, Perrin N, Hanson G, Mankowski E, Bloom T, Campbell J. Patterns of partners' abusive behaviors as reported by Latina and non-Latina survivors. J Community Psychol. 2009;37:156–170. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galvez G, Mankowski ES, Braun MF, Glass N. Development of an iPod audio computer-assisted self-interview to increase the representation of low-literacy populations in survey research. Field Methods. 2009;21:407–415. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bloom T, Wagman J, Hernandez R, Yragui N, Hernandez-Valdovinos N, Dahlstrom M. Partnering with community-based organizations to reduce intimate partner violence. Hisp J Behav Sci. 2009;31:244–257. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mankowski ES, Galvez G, Glass N. Interdisciplinary linkage of community psychology and cross-cultural psychology: history, values, and an illustrative research and action project on intimate partner violence. Am J Community Psychol. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9377-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perrin NA, Yragui NL, Hanson GC, Glass N. Patterns of workplace supervisor support desired by abused women. J Interpers Violence. 2010 doi: 10.1177/0886260510383025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anger WK, Rohlman DS, Kirkpatrick J, Reed RR, Lundeen CA, Eckerman DA. cTRAIN: a computer-aided training system developed in SuperCard for teaching skills using behavioral education principles. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput. 2001;33:277–281. doi: 10.3758/bf03195377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Social Sciences. 1st ed. Hillsdale (MI): Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anger WK, Tamulinas A, Uribe A, Ayala C. Computer-based training for immigrant Latinos with limited education. Hispanic J Behavioral Sci. 2004;26:373–389. [Google Scholar]