Infant leukemia, diagnosed in the first 12 months of life, is extremely rare in the United States; the overall annual incidence is estimated to be approximately 37 cases per million infants (1). Certain demographic information with respect to incidence may provide important clues regarding etiology. White infants experience about a 50% higher risk than black infants, and females about a 50% higher risk than males (1). The observation of a higher risk in infant females is particularly notable given the overall higher risk of leukemia (≈30%) in male children under the age of 15 as compared with female children (2).

With the exception of in utero exposure to radiation and prior chemotherapy treatments, little is known about the causes of childhood leukemia (reviewed in ref. 2). This paucity of information is likely attributable largely to the heterogeneity of the disease and to insufficient study power to test hypotheses within more homogenous subgroups. In particular, age at diagnosis and/or biologically distinct subgroups are likely reflective of different etiologic mechanisms.

Several epidemiologic studies have observed specific risk factors that are fairly consistently associated with younger children who develop leukemia (reviewed in refs. 2 and 3). These include (i) a birth weight in excess of 4,000 g [a 2-fold increased risk associated with both acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) in children under the age of 2]; (ii) maternal alcohol consumption during pregnancy (a 1.5-fold increased risk associated with infant AML); and (iii) maternal history of miscarriage or stillbirth (2- to 5-fold excess risks of infant AML and ALL).

Biologically, infant leukemias represent a distinct group for the epidemiologic study of hematopoietic neoplasms. The majority of infant cases (including about 80% of infants with ALL and 65% of infants with AML) have rearrangements involving the MLL gene on chromosome band 11q23 in their leukemia cells (4–6). This finding is in contrast to children diagnosed after 1 year of age, where the frequency of MLL rearrangements is about 5% (7). For infants, there is strong molecular evidence that these MLL abnormalities occur in utero (8, 9). Intriguingly, identical MLL gene rearrangements have been observed in treatment-related leukemia (most often, AML) that can develop in children and adults after therapy for a primary cancer (10, 11). This form of treatment-related leukemia is associated with drugs that inhibit DNA topoisomerase II, including the epipodophyllotoxins, etoposide and teniposide. The involvement of epipodophyllotoxins in DNA topoisomerase II inhibition is postulated to be directly related to the MLL abnormalities observed in the secondary AMLs.

Based on the findings from treatment-related leukemias, and the biological evidence that infant leukemia likely occurs in utero, we hypothesized that maternal exposure to DNA topoisomerase II inhibitors during pregnancy could be associated with an increased risk of infant leukemia (12). Natural and synthetic DNA topoisomerase II inhibitors include (i) the flavonoids, e.g., quercetin (found in certain fruits and vegetables) and genistein (soy); (ii) catechins (found in tea, wine, and chocolate); (iii) caffeine; (iv) the quinolones (found in certain medications used to treat urinary and respiratory tract infections); (v) thiram (an agricultural fungicide); (vi) specific derivatives of benzene; and (vii) Chinese herbal medicines (12–13). Our preliminary epidemiologic study suggested that increased maternal consumption during pregnancy of foods that contain dietary topoisomerase II inhibitors is positively associated with infant AML only, similar to the observations in the treatment-related leukemias (14). However, these findings were cautiously interpreted, in part, because of the lack of available biological data in our study regarding MLL involvement in the infants with leukemia and also because of a lack of evidence in the literature that supported the following necessary assumptions: (i) dietary constituents that inhibit DNA topoisomerase II can have a direct effect on the MLL gene, and (ii) these compounds can cross the placenta and reach the fetus.

Strick et al. (15) wished to determine whether bioflavonoids that mothers might consume from foods or supplements during pregnancy directly target the MLL gene. [In support of their study, they cite recent evidence from an animal study suggesting that flavonoids do cross the placenta (16).] In a series of elegantly conducted experiments, Strick and colleagues (15) demonstrate that several of the bioflavonoids available in the diet can induce cleavage of the MLL gene in human myeloid and lymphoid progenitor cells and in cell lines. Importantly, they found that the site of cleavage colocalizes with cleavage sites induced by chemotherapeutic agents known to inhibit DNA topoisomerase II. These findings provide evidence that dietary flavonoids may be directly involved in causing genetic damage, as is the case with dietary exposure to aflatoxins and specific p53 mutations observed in liver cancer (17). Furthermore, Strick et al. demonstrate rapid reversibility of the cleavable complex after removal of the bioflavonoids. These illuminating data mandate further work to characterize the potential role of dietary flavonoids in leukemia. In particular, several questions need to be addressed.

(i) Are the molecular events leading to infant AML with an MLL rearrangement different from those leading to infant ALL? Strick et al. evaluated the occurrence of MLL breaks caused by DNA topoisomerase II inhibitors in myeloid and lymphoid progenitors and observed similar results in both. However, very few therapy-related ALLs are associated with epipodophyllotoxin use; in almost all cases, the leukemias are myeloid in type. Moreover, our preliminary data with respect to maternal ingestion of dietary topoisomerase II inhibitors suggest a relationship with infant AML but not ALL (14). However, nearly 80% of infants with ALL have MLL involvement as compared with about 65% of infants with AML. Therefore, although MLL is a critical gene involved in leukemogenesis, the mechanisms leading to the disruption of the gene in lymphoid and in myeloid cells may be different. This hypothesis needs to be evaluated in additional biological and population-based studies.

(ii) Could the mechanism of flavonoid-induced MLL breaks be important in adult leukemias as Strick et al. suggest? Although this is possible, the occurrence of MLL abnormalities in adult de novo leukemia is quite low, with estimates suggesting only about 5% of cases affected (18). Also, no epidemiologic data support an important role of diet in adult AML, although this has not been studied to any great extent. Hematopoietic stem cells seem to display ontogenetic age-dependent differences in growth properties. For example, there is a notably decreased clonogenic potential and proliferative responsiveness in mixed lymphocyte reaction assays observed in adult hematopoietic stem cells as compared with stem cells isolated from fetal bone marrow (19). Because proliferating cells express higher levels of DNA topoisomerase II as compared with quiescent cells (20), a fetus, who has periods of rapid cell turnover, may be more susceptible than an adult to the effect of dietary DNA topoisomerase II inhibitors. Perhaps one way to approach this question is to determine whether the flavonoids (and other DNA topoisomerase II inhibitors) can cause cleavage of other genes (such as AML-1 on chromosome 21) that are associated with de novo leukemia in older children and adults and also with DNA topoisomerase II inhibitor chemotherapies (21).

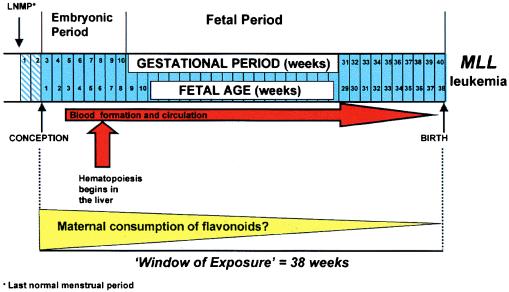

(iii) Given the ubiquity of the dietary exposure, why is leukemia in infancy so rare? To answer this question, we must consider several factors, including the timing of exposures and the inherent genetic susceptibility of individuals. For some birth defects, critical times for development have been established. For instance, a critical time point for neural tube development is in the third week of life (22), and, therefore, the importance of folate supplementation immediately before conception to prevent neural tube defects has been established (23). For infant leukemia, it is unclear when the fetus might be most vulnerable. The formation of blood cells occurs in the yolk sac by the third week of fetal life and then gradually shifts to the liver, which becomes the predominant site of hematopoiesis by the sixth week of fetal life (22) (Fig. 1). We have learned from the therapy-related leukemias that frequent (weekly) exposure to DNA topoisomerase II inhibitor drugs may increase risk (21). In utero, there may be a critical interval when exposure to high levels of flavonoids and increased hematopoietic cell proliferation can lead to recombinations involving MLL; given the timing of development of hematopoiesis, this exposure may be more critical earlier in fetal life (Fig. 1). This event must, however, be strongly influenced by other factors, including the capacity for DNA repair and individual variations in the capacity to metabolize particular flavonoids. Current molecular epidemiologic studies of infant leukemia in the United States and Europe are designed to address some of these questions.

Figure 1.

A possible pathway to infant leukemia.

(iv) Finally, do common flavonoids cross the placental barrier in humans? Strick et al. cite a study conducted by Schroder-van der Elst et al. (16), in which a radioactive synthetic flavonoid was injected into pregnant rats. All fetal tissues investigated demonstrated the presence of the flavonoid, suggesting that it crossed the placental barrier. However, further studies are needed to determine whether ingestion of common dietary flavonoids by humans results in a similar phenomenon.

Given the small time window of exposure, infants represent an ideal population for epidemiologic studies of diet and leukemia. Strick et al.'s study provides another important piece of the puzzle that supports the hypothesis that maternal exposure to dietary DNA topoisomerase II inhibitors may be associated with an increased risk of infant leukemia. The above observations highlight the complexity of exposure–disease relationships and underscore the importance of collaborations among several scientific disciplines in forming tenable hypotheses. As Strick et al. note, in most epidemiologic studies of human cancers, increased consumption of foods that contain flavonoids is associated with a decreased risk of adult malignancies (including prostate, colon, and lung). Because cell cycling is a dynamic process, it should be remembered that what might be beneficial at one point in time could be harmful at another.

Acknowledgments

I thank Drs. Les Robison, Stella Davies, John Perentesis, and John Potter for their insightful comments over the years as this hypothesis has developed. I would also like to thank Ms. Catherine Moen for editorial assistance. This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute (R01CA42479, R01CA49450, R01CA58051, T3209607, R01CA79940, and R01CA75169) and the Children's Cancer Research Fund at the University of Minnesota.

Footnotes

See companion article on page 4790.

References

- 1.Gurney J G, Ross J A, Wall D A, Bleyer W A, Severson R K, Robison L L. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1998;19:428–432. doi: 10.1097/00043426-199709000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ross J A, Davies S M, Potter J D, Robison L L. Epidemiol Rev. 1994;16:243–272. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ross J A, Perentesis J P, Robison L L, Davies S M. Cancer Causes Control. 1996;7:500–506. doi: 10.1007/BF00051889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen C-S, Sorensen P H B, Domer P H, Reaman G H, Korsmeyer S J, Heerema N A, Hammond G D, Kersey J H. Blood. 1993;81:2386–2393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sorensen P H B, Chen C-S, Smith F O, Arthur D C, Domer P H, Bernstein I D, Korsmeyer S J, Hammond G D, Kersey J H. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:429–437. doi: 10.1172/JCI116978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cimino G, Lo Coco F, Biondi A, Eilia L, Luciano A, Croce C M, Masera G, Mandelli F, Canaani E. Blood. 1993;82:544–546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taki T, Ida K, Bessho F, Hanada R, Kikuchi A, Yamamoto K, Sako M, Tsuchida M, Seto M, Ueda R, Hayashi Y. Leukemia. 1996;10:1303–1307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ford A M, Ridge S A, Cabrera M E, Mahmoud H, Steel C M, Chan L C, Greaves M. Nature (London) 1993;363:358–360. doi: 10.1038/363358a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gale K B, Ford A M, Repp R, Borkhardt A, Keller C, Eden O B, Greaves M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:13950–13954. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Felix C A, Hosler M R, Winick N J, Masterson M, Wilson A E, Lange B J. Blood. 1995;85:3250–3256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cimino G, Raponotti M C, Biondi A, Elia L, Lo Coco F, Price C, Rossi V, Rivolta A, Canaani E, Croce C M, et al. Cancer Res. 1997;57:2879–2883. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ross J A, Potter J D, Robison L L. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;86:1678–1680. doi: 10.1093/jnci/86.22.1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greaves M F. Lancet. 1997;349:344–349. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)09412-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ross J A, Potter J D, Reaman G H, Pendergrass T, Robison L L. Cancer Causes Control. 1996;7:581–590. doi: 10.1007/BF00051700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strick R, Strissel P L, Borgers S, Smith S L, Rowley J D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:4790–4795. doi: 10.1073/pnas.070061297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schroder-van der Elst J P, van der Heide D, Rokos H, Morreale de Escobar G, Kohrle J. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:E253–E256. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1998.274.2.E253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hussain S P, Harris C C. Mutat Res. 1999;428:23–32. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(99)00028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Macintyre E, Bourquelot P, Leboeuf D, Rimokh R, Archimbaud E, Smetsers T, Zittoun R. Blood. 1997;89:2224–2226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu A G, Michejda M, Maumder A, Meehan K R, Menendez F A, Tchabo J-G, Slack R, Johnson M P, Bellanti J A. Pediatr Res. 1999;46:163–169. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199908000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zandvliet D W, Hanby A M, Austin C A, Marsh K L, Clark I B, Wright N A, Poulsom R. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1307:239–247. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(96)00063-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Felix C A. In: Multiple Primary Cancers. Neuget A I, Meadows A T, Robison E, editors. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1999. pp. 137–164. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moore K L, Persaud T V N, editors. The Developing Human: Clinically Oriented Embryology. 6th Ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Locksmith G J, Duff P. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:1027–1034. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00060-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]