Abstract

In recent years, various international organizations have raised awareness regarding psychosocial risks and work-related stress. European stakeholders have also taken action on these issues by producing important documents, such as position papers and government regulations, which are reviewed in this article. In particular, 4 European models that have been developed for the assessment and management of work-related stress are considered here. Although important advances have been made in the understanding of work-related stress, there are still gaps in the translation of this knowledge into effective practice at the enterprise level. There are additional problems regarding the methodology in the evaluation of work-related stress. The European models described in this article are based on holistic, global and participatory approaches, where the active role of and involvement of workers are always emphasized. The limitations of these models are in the lack of clarity on preventive intervention and, for two of them, the lack of instrument standardization for risk evaluation. The comparison among the European models to approach work-related stress, although with limitations and socio-cultural differences, offers the possibility for the development of a social dialogue that is important in defining the correct and practical methodology for work stress evaluation and prevention.

Keywords: Workplace, Stress psychological, Risk assessment

Introduction

Work-related psychosocial risks concern aspects of work design, management, and the social and organizational contexts that can cause psychological or physical harm. Work-related stress is among the most commonly reported causes of workrelated illness, affecting more than 40 million individuals across the Eropean Union (EU) [1].

In recent years various international organizations have set initiatives in motion to raise awareness regarding the psychosocial risks of work-related stress. In 1999, the European Parliament urged the European Commission to analyze additional problems that were not covered by existing legislation, such as stress, fatigue, and aggression [2]. The World Health Organization, in its Ministerial Conference on Mental Health in 2005, emphasized the importance of mental health, well-being and prevention, treatment, care and rehabilitation for mental health problems; these issues were referred to the context of the workplace, and acknowledged the important role of research. In addition, European social partners have started to take action, by first publishing important relevant documents. The objectives of this paper are: 1) to review the main European documents and directives concerning work-related stress; and 2) to examine four models, developed by European countries, for the assessment and management of work-related stress.

Some European Documents and Directive Concerning Work-Related Stress

In 1989, the European Commission Council Framework Directive provided its first significant approach towards the prevention of work-related stress and the management of psychosocial risks in the document, Introduction of Measures to Encourage Improvements in the Safety and Health of Workers at Work (89/391/EEC) [3]. This Directive was based on the principles of prevention and concerned all types of risk for workers' health [4]. Following this directive, all employers have a legal obligation to protect the occupational safety and health of workers. This duty applies to problems of work-related stress and is reflected in the labour legislation of many European-member states. Based on this legislation, a new culture for psychosocial risk prevention has been established in Europe, combining legislation, social dialogue, the promotion of best practices, and corporate social responsibility [4].

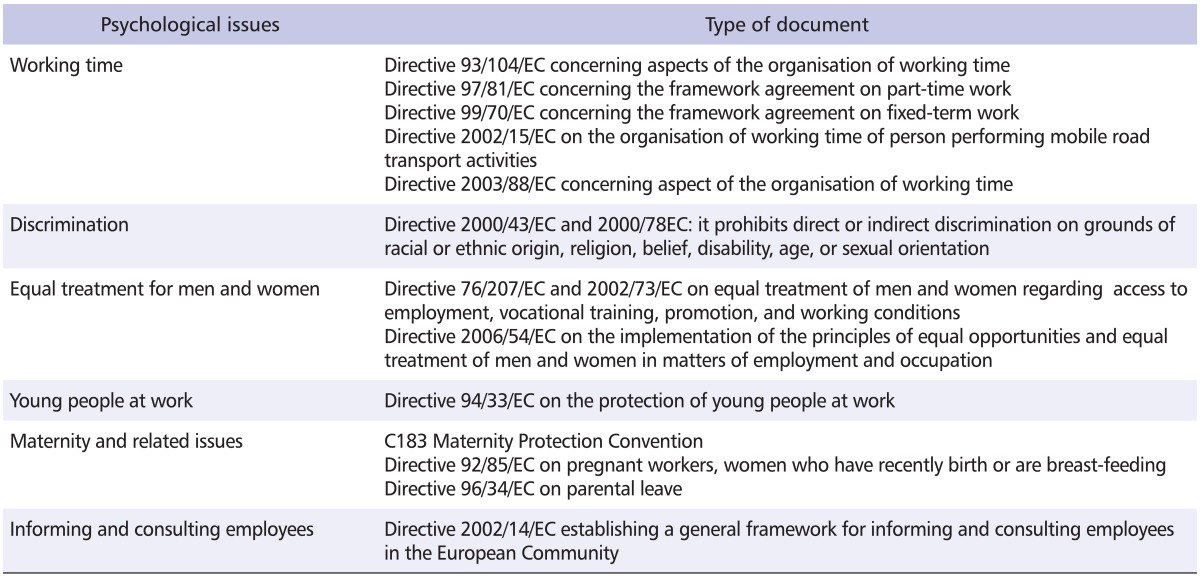

An important document concerning work-related stress was published in 2000 by the European Commission; the "Guidance on Work-Related Stress" [5], in which stress was defined as "a pattern of emotional, cognitive, behavioral and physiological reactions to adverse and noxious aspects of work content, work organization and work environment." The main causes of stress were listed as the following: over- and under workloads; lack of recognition; no opportunity to voice complaints; excess responsibilities with little authority; lack of a clear job description; uncooperative or unsupportive superiors; co-workers or subordinates; lack of control on the job; job insecurity; exposure to prejudice (based on age, gender, etc.); exposure to violence, threats, or bullying; unpleasant or hazardous physical work conditions; and no opportunity to utilize personal abilities. Organizational improvements were recommended in the following areas, as stress prevention measures: work schedule, participation/control, workload, task content, roles and social environment. The European document outlined important prevention steps: i) identification of work-related stress factors, their causes and health consequences; ii) analysis of the characteristics of exposures in relation to the outcomes; iii) design and implementation of intervention strategies by stakeholders; and iv) evaluation of short- and long-term results of interventions. In the same years, the International series of the Standard ISO 10075, part 1 and 2 related to mental work load [6] have been adopted and published as European Standards. Mental stress is defined as: "the total of all assessable influences impinging upon a human being from external sources and affecting it mentally." Mental strain is correspondingly defined as the "immediate effect of mental stress within the individual (not the long-term effect) depending on his/her individual habitual and actual preconditions, including individual coping styles". According to the European Standards, the consequences of mental strain included boredom and feelings of being overloaded, which are not dealt with in the Standard, "due to large individual variation, or to as yet inconclusive results of research." The document lists 29 task features that influence the intensity of mental workload and are sources of fatigue (e.g., ambiguity of task goals, complexity of task requirements, adequacy of information, ambiguity of information, signal discrimination). The Standard point out that mental workload is not a one-dimensional concept, however that there are different qualitative aspects leading to different qualitative effects; additional guidelines concerning fatigue, monotony, reduced vigilance, and mental satiation are provided. In October 2004, the framework agreement on work-related stress was signed [7]. In this document stress is described as a state that is accompanied by physical, psychological or social complaints or dysfunctions. The aim of the agreement was, as stated in the document, "to increase the awareness and understanding of employers, workers and workers' representatives on the causes of work-related stress, and to draw their attention to signs that could indicate problems of work-related stress". It provided employers and workers with a framework to identify and to prevent or manage problems of work-related stress. Furthermore it provided a non-exhaustive list of potential stress factors which can help to identify eventual problems: high absenteeism or staff turnover, frequent interpersonal conflicts or complaints by workers are identified as relevant signs that may indicate a problem of work-related stress. The agreement highlights a number of collective and individual measures that can be considered as specific towards the identification of stress factors or as part of an integrated stress policy that encompasses both preventive and responsive measures. The agreement stated: "to identify a problem of work-related stress involves an analysis of factors, such as work organization and processes (work time arrangements, degree of autonomy, match between workers' skills and job requirements, workload, etc.), working conditions and environment (exposure to abusive behaviour, noise, heat, dangerous substances, etc.), communication (uncertainty about what is expected at work, employment prospects, or forthcoming change, etc.) and subjective factors (emotional and social pressures, feeling unable to cope, perceived lack of support, etc.)". Other significant directive concerning work conditions, are reported in Table 1 [8].

Table 1.

Directive related to psychosocial risks at work [8] (from PRIMA-EF)

PRIMA-EF: Psychosocial Risk Management Excellence Framework.

The Implementation of the European Framework Agreement on Work-related Stress

The implementation of the European framework on work-related stress was scheduled to have been carried out within three years after the date of signing the agreement. The report by the European Social Partners [9], adopted on June 2008, described the activities of the European states, the choice of instruments and strategies to implement the European agreement, the challenges encountered in implementation and the link to concrete implementation and dissemination results, for each state. In most EU-member states, implementation started with the translation of the agreement followed by dissemination actions, such as campaigns to raise awareness that involved websites, brochures, guides, and training schemes. In addition, the Implementation is reflected in many member states' labour legislation. In some cases social partners have agreed that the issue of stress at work was already covered in existing national legislation (Norway, Denmark); in other cases existing legislation was amended to take into account the European framework agreement. For example, as reported by the Implementation Document, in the Czech Republic the content of the European agreement was integrated via amendments into the new labour code (Law number 262/0226 Coll. of April 21, 2006 in force since January 1, 2007) [10], which obliged employers to create safe working conditions and to adopt measures for assessing, preventing, and eliminating risks. In Belgium, the Royal Decree of May 2007 [11] concerning the prevention of psychosocial burdens caused at work extended, the application of the 1999 [12] inter-professional collective agreement on management and prevention of work-related stress to the public sector. The Royal Decree obliged every employer to analyse and identify all situations that might entail a psychosocial burden. In the Slovak Republic, the efforts to implement the framework agreement found their expression in new labour legislation; in particular the Labour Code (Law 311/2001), the Health and Safety at Work Law, the Labour Inspection Law, as well as several sectorial legal regulations. The Labour Code requires that employers take measures to protect the life and health of employees at work and create a safe labour environment for employees. According to the experts, the Polish law provides several relevant provisions. In Hungary, the Parliament amended the Health and Safety at Work Act (Act CLXI of 2007), which includes stress the health risks at work as a psychosocial hazard and define it. The amendments became effective on January 1, 2008. In Italy, the public and private employers are called to assess their employees' level of health-risks related to the stress. In this regard, according to the European Framework Agreement and to the legislative decree number 81/2008, specific guidelines were set up. The article 28, paragraph 1, of legislative decree number April 9, 2008, number 81 (legislative decree number 81/2008) [13] stated that the risk assessment must cover all risks, including specifically those linked to work-related stress, those concerning pregnant workers, and those linked to differences in gender, age, and nationality. An important document that contain the recommendations for stress assessment is the Circular Letter dated November 18 2010 - Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs - General Directorate of the Protection of Working Conditions; this will be described in the next chapters.

Models for Assessment and Management of Psychosocial Risks in Some European Countries

After an examination of the models developed in some European-member states, we selected four that are oriented to a holistic approach aimed towards preventing occupational psychosocial risks: the Management Standard for work-related stress (United Kingdom), START (Germany), the Screening, Observation, Analysis, Expertise (SOBANE, Belgium), and National Institute for Prevention and Safety at Work (INAIL-ISPESL) model (Italy).

United Kingdom: the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) Management Standard approach

The Management Standards approach, developed by HSE [14] requires that managers, employees, and employees' representatives work together to improve certain aspects of work, described in the Standards, which will have a positive effect on employee well-being. The method is divided into main steps, while there is also a preparatory stage involving setting up and communicating the process in order to gain support from stakeholders.

Step 1- Identify the risks

The model identifies six areas of work that can have a negative impact on employee health if not properly managed. These areas ("Management Standard") are: Demands (includes workload, work patterns and the work environment); Control (is the amount of 'say' an individual considers they have in how their work is carried out); Support (encouragement, sponsorship and resources provided by the organisation, management and colleagues); Role (whether people understand their role within the organisation and whether the organisation ensures that they do not have conflicting roles); Change (how organisational change is managed and communicated in the organization); and Relationships (promoting positive working to avoid conflict and dealing with unacceptable behaviour).

Step 2- Decide who might be at risk and how

The second step requires specific data to indentify potential target subjects. Typical data to collect include: sickness absence data, staff turnover rates, number of referrals to occupational health and information from existing staff forums. The model suggests that these data are to be integrated with those collected through the HSE Management Standards Indicator Tool, a 35-item questionnaire, which examines employees' view.

Step 3- Evaluate the risk

After the analysis of the results from Step 2, along with the indicator tool results, is it possible to identify priority and problematic areas that should be discussed with employees. Then, the model requests a check of the results of the analysis with the employees. Focus groups are a good tool to ensure that employees and their representatives are involved in discussions. The outcomes of the focus group discussions should be a set of suggested actions aimed at addressing specific issues.

Step 4- Record the findings

This step involves the development and implementation of action plans suggested by the focus groups. The planning of interventions involves the definition of objectives, priorities, roles, and resources according to the results of the risk-stress evaluation, especially in relation to critical areas.

Step 5- Monitor and review

In this phase, evaluators have to monitor the actions in the plan (to ensure they are having the desired effect in the appropriate timescale) and to think about what is possible to do in the future to prevent the problems identified. It is also important to explain to managers that good stress management is not about a survey, but is an ongoing process of continuous improvement.

Germany: the START procedure

The 'START process' [15] falls in the area of preventive health measures. The process enables workplace practitioners to evaluate psychological stress and, by deriving corresponding measures, to reduce or even do away with sources of stress [16].

The cyclical sequence of risk management of the START process includes the following steps: 1) information and participation of workers (training measures); 2) identification of workplace risks (using the START questionnaires, that is composed by 50 items, divided in 13 areas, and a checklist for on-site analysis); 3) evaluation of the risks identified; 4) derivation and implementation of measures to improve occupational health and safety; 5) documentation of results; 6) monitoring of effectiveness of the measures taken; and 7) repetition at regular intervals and whether or not there are changes.

Belgium: SOBANE

The SOBANE [17] is a strategy of risk prevention that includes four levels of intervention; it involves the active participation of staff in screening for potential safety risks and in finding solutions. The 4 steps, as described by the European Working Conditions Observatory [18], are: 1) Screening: the workers and their management detect the risk factors and implement obvious; 2) Observation: each of the remaining problems are examined in more detail, and the reasons and solutions are discussed; 3) Analysis: when necessary, an occupational health practitioner is asked to carry out appropriate measurements to develop specific solutions; 4) expertise: in complex and rare cases, the assistance of an expert is called on to solve a particular problem.

Italy: the INAIL-ISPESL model

In order to provide a practical tool for the assessment of work-related stress, the INAIL-ISPESL ad hoc research group carried out a benchmarking analysis of the various models to manage work stress problems adopted by EU countries. This model chose to apply and implement the HSE Management Standards approach in the Italian context, and considered the indications of the Circular Letter by the Italian Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs and the Legislative Decree 81/2008. The Circular Letter (November 18 2010) stated that stress assessment has to be divided into two steps. A preliminary one, in which objective parameters must be considered, as pertaining to three distinct areas:

Sentinel events such as: injury rates, sick leave, turnover, procedures and sanctions, reports of physicians and specific and frequent formal complaints by workers.

Work content factors such as: work environment and equipment, workloads, working hours and shifts; match between worker skills and professional qualifications required.

Contextual factors of work such as: role in the organization, decision-making autonomy and control, interpersonal conflicts at work, development and career development, communication.

If the preliminary assessment provides no evidence of work-related stress the employer is only required to give account in the document of risk assessment (document of risk evaluations, DVR) and provide a monitoring plan. Otherwise, if there are elements of stress risk, it is necessary to plan and to adopt appropriate corrective actions; if these actions are ineffective, the evaluation should be continued. The detailed evaluation includes the assessment of subjective perceptions of workers through questionnaires, focus groups and semi-structured interviews. This phase refers to homogeneous groups of workers in respect to the problems detected.

The INAIL-ISPESL model is composed of the following phases

1) Preparatory phase: this phase, before the evaluation, is the preparation of the key element of all the evaluation process (establishment of the group for the stress assessment; development of a communication strategy and staff involvement, development of risk assessment plan); 2) Preliminary evaluation: the model propose a checklist, to evaluate three areas of indicators: sentinel events (10 indicators); work content factors (4 areas) and contextual factors of work (6 areas). Each indicator is assigned a score that contributes to the overall score of the area. The scores of the 3 areas are added, so that the level of risk could be defined. If the level of risks is low, the process of stress evaluation is completed; if the risks results medium or high, it is necessary to carry out corrective actions (e.g., organizational, technical, procedural, communication, training); if these action, after a monitoring conducted with the same "checklists", are ineffective, there is the third phase; 3) Detailed evaluations: it consists in the assessment of workers' subjective perceptions, through the administration of the HSE Management Standards Indicator Tool.

Discussion

There is evidence in Europe that work plays an important role in relation to mental health [4]. Important laws and agreements have been elaborated upon by European stakeholders in order to share a common set of regulations across Europe. Although important progress has been made to advance the knowledge in relation to these issues, there are still gaps in the translation of this knowledge into effective practice at the enterprise level [4]. Among the reasons for this delay is the lack of awareness across the European countries, which is often associated with a lack of expertise, research, and appropriate infrastructure [19].

Another important problem concerns the methodology of stress evaluation. The identification of a valid methodology for the evaluation of work-related stress is difficult, because of the many potential co-factors. The European models for stress evaluation described in this article follow a holistic, global and participatory approach: the active role and the necessity of workers' involvement are always emphasized.

The comparison between the European models, although limited due to socio-cultural differences, offers a model of social dialogue to approach work stress assessment and prevention. In this context, the Italian legislation has introduced the mandatory assessment of work stress for each employer. A limitation of this approach is represented by the predominant relevance given to the assessment of objective factors in the first steps of the evaluation. Subjective assessment is considered only in a second phase, whereas the EU Framework underlines the importance of the subjective component in each step: i) definition phase (articles 1-3), ii) methodology (article 4), iii) assessment of the effects of stress on workers' health (article 3). Furthermore, several studies and reviews have pointed out the importance of collecting subjective and objective data in work-related stress assessment [20-22]. Nevertheless, this normative is a very important because the first example at the EU level of a mandatory approach to work-related stress for both public and private sectors.

The use of objective measures can contribute to a clearer linkage between subjective perception and the environmental conditions and can indicate what aspects should be modified by preventive interventions. On the other hand, subjective measures are needed because the impact of exposure varies substantially among individuals; moreover, they examine cognitive and emotional processing. Therefore, the best approach to measure work-related stress is an integrated one, which involves the use of multiple subjective and objective assessment modalities.

In conclusion, despite the development of knowledge and activities on both the policy and practice levels in recent years, further work is still needed to harmonize stakeholder perceptions in this area within the EU member states [23]. However, it has been acknowledged that the initiatives that aim to promote workers' health have not resulted in a positive impact as anticipated by experts and policy makers [24]. The main reason for this is likely represented by the gap existing between policy and practice [25]. At the organisational level, there is a clear need for the implementation of systematic and effective prevention strategies, linked to companies' management practices [26].

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Parent-Thirion A, Macías EF, Hurley J, Vermeylen G European Foundation for the improvement of living and working conditions. Fourth European Working Conditions Survey [Internet] Dublin (UK): European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions; 2007. [cited 2010 Aug 23]. p. 139. Available from: http://www.eurofound.europa.eu/pubdocs/2006/98/en/2/ef0698en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Natali E, Rondinone B, Petyx C, Iavicoli S. PRIMA-EF, Guidance Sheets number 5 [Internet] Nottingham (UK): PRIMA-EF; 2008. [cited 2010 Aug 23]. The perception of psychosocial risk factors among European stakeholders; p. 2. Available from: http://prima-ef.org/Documents/05.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Council of the European Communities. Council Directive 89/391/EEC of 12 June 1989 on the introduction of measures to encourage improvements in the safety and health of workers at work. Off J Eur Communities. 1989;32:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leka S, Kortum E. A European framework to address psychosocial hazards. J Occup Health. 2008;50:294–296. doi: 10.1539/joh.m6004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levi L, Levi I. Guidance on work-related stress. Spice of life, or kiss of death? Luxembourg (Luxembourg): Office for Official Publications of the European Communities; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 6.European Committee for Standardization. Ergonomic principles related to mental work load-Part 1: General terms and definitions (EN ISO 10075-1) and Part 2: Design principles. Brussels (Belgium): CEN; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Framework agreement on work-related stress [Internet] Nottingham (UK): ETUC, UNICE, UEAPME, CEEP; 2004. [cited 2010 Aug 23]. Available from: http://www.etuc.org/IMG/pdf_Framework_agreement_on_work-related_stress_EN.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 8.European and International Standards Related to Psychosocial Risks at Work. Guidance Sheets number 7 [Internet] Nottingham (UK): PRIMA-EF; 2008. [cited 2010 Aug 23]. Available from: http://prima-ef.org/Documents/07.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Implementation of the European autonomous framework on work-related stress [Internet] Nottingham (UK): ETUC, BUSINESSEUROPE, UEAPME, CEEP; 2008. [cited 2010 Aug 23]. Available from: http://www.etuc.org/IMG/pdf_Final_Implementation_report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 10.The Czech Republic. Labour code (Law number 262/2006 Coll.). Article section 102 [Internet] 2006. [cited 2010 Aug 23]. Available from: http://www.mpsv.cz/files/clanky/3221/labour_code.pdf.

- 11.Federal Public Service Employment, Labour and Social Dialogue. Royal Decree of 2007 May 17 [Internet] 2007. [cited 2010 Aug 23]. Available from: http://www.emploi.belgique.be/moduleTab.aspx?id=2894&idM=102.

- 12.Convention collective de travail n° 72 du 30 mars 1999 concernant. La gestion de la prévention du stress occasionné par le travail (ratifiée par l'AR du 21 juin 1999 paru au MB du 9 juillet 1999) [Internet] 1999. [cited 2010 Aug 23]. Available from: http://www.ulb.ac.be/cgsp/CPPTULB/CONVENTIONCOLLECTIVEDETRAVAIL72.htm. French.

- 13.J Ital Repub no. 101, Ordinary Supplement. 2008. Apr 30, Italian Legislative Decree no. 81 of 9 April 2008. Safety Consolidation Act. Implementation of Article 1 of Law no. 123 of 3 August 2007 on the protection of health and safety at work. Italian. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Health and Safety Executive. Managing the causes of work related stress. A step-by-step approach using Management Standards. Nottingham (UK): Health and Safety Executive Books; 2007. p. 56. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Satzer R, Gerey M. Stress-Mind-Health, the START procedure for the risk assessment and risk management of workrelated stress. Arbeitspapier 174. Düsseldorf (Germany): Hans-Böckler-Stiftung; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marino D, Langhoff T. Stress-Psychology-Health: the START process fro assessing the risk posed by work-related stress. Mag Eur Agency Saf Health Work. 2008;11:42–45. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malchaire J, Malchaire J, D'Horre W, Stordeur S. The Sobane strategy applied to the management of psychosocial aspects. Direction Générale Humanisation du Travail; 2008. p. 35. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Risk management strategy tackles health and safety problems [Internet] European Working Conditions Observatory. 2007. [cited 2010 Aug 23]. Available from: http://www.eurofound.europa.eu/ewco/2007/12/BE0712019I.htm.

- 19.Leka S, Cox T, Kortum E, Iavicoli S, Zwetsloot G, Lindstrom K, Ertel M, Jain A, Hassard J, Hallsten L, Makrinov N. Towards the development of a european framework for psychosocial risk management at the workplace. Nottingham (UK): I-WHO Publications; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frese M, Zapf D. Methodological issues in the study of work stress: objective vs. subjective measurement of work stress and the question of longitudinal studies. In: Cooper C, Payne R, editors. Causes, coping and consequences of stress at work. Chichester (UK): Wiley; 1988. pp. 375–411. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hurrell JJ, Jr, Nelson DL, Simmons BL. Measuring job stressors and strains: where we have been, where we are, and where we need to go. J Occup Health Psychol. 1998;3:368–389. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.3.4.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Albini E, Zoni S, Parrinello G, Benedetti L, Lucchini R. An integrated model for the assessment of stress-related risk factors in health care professionals. Ind Health. 2011;49:15–23. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.ms948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iavicoli S, Natali E, Deitinger P, Maria Rondinone B, Ertel M, Jain A, Leka S. Occupational health and safety policy and psychosocial risks in Europe: the role of stakeholders' perceptions. Health Policy. 2011;101:87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leka S, Jain A, Zwetsloot G, Vartia M, Pahkin K. In: The European framework for psychosocial risk management: PRIMA-EF. Leka S, Cox T, editors. Nottingham (UK): I-WHO Publications; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leka S, Jain A, Iavicoli S, Vartia M, Ertel M. The role of policy for the management of psychosocial risks at the workplace in the European Union. Safety Sci. 2011;49:558–564. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leka S, Jain A, Zwetsloot G, Cox T. Policy-level interventions and work-related psychosocial risk management in the European Union. Work Stress. 2010;24:298–307. [Google Scholar]