Summary

Background and objectives

The extent to which racial and socioeconomic disparities in access to kidney transplantation are related to not being assessed for transplant suitability before or shortly after the time of initiation of dialysis is not known. The aims of this study were to determine whether there were disparities based on race, ethnicity, or type of insurance in delayed assessment for transplantation and whether delayed assessment was associated with lower likelihood of waitlisting and kidney transplantation.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

This retrospective cohort study used data from the US Renal Data System and included 426,489 adult patients beginning dialysis in the United States between January 1, 2005 and September 30, 2009 without prior kidney transplant.

Results

Overall, 12.5% of patients had reportedly not been assessed for transplantation. Patients without private insurance were more likely to be reported as not assessed (multivariable adjusted odds ratio=1.33, 95% confidence interval=1.28–1.40 for Medicaid), with a pronounced racial disparity but no ethnic disparity among patients aged 18 to <35 years (odds ratio=1.27, 95% confidence interval=1.13–1.43; P<0.001 for interaction with age). Not being assessed for transplant around the time of dialysis initiation was associated with lower likelihood of waitlisting in multivariable analysis (hazard ratio=0.59, 95% confidence interval=0.57–0.62 in the first year) and transplantation (hazard ratio=0.46, 95% confidence interval=0.41–0.51 in the first year), especially within the first 2 years.

Conclusions

Racial and insurance-related disparities in transplant assessment potentially delay transplantation, particularly among younger patients.

Introduction

For patients with ESRD, kidney transplantation is associated with longer survival and better quality of life than dialysis (1–4). However, disparities in transplantation rates based on black race and neighborhood poverty have been consistently documented (2,5–8). Investigations into the possible reasons for racial disparities indicate inequality at nearly every step in the process, starting with referral for transplantation and continuing through placement on the kidney transplant waiting list and eventual receipt of a renal allograft (4,6,9–11). Although lower socioeconomic status and lack of insurance may explain some of the disparity, black race is associated with lower rates of transplantation even after adjusting for these parameters (7). Personal and cultural beliefs and preferences may also be factors (12,13). One study showed that black individuals had less conviction that kidney transplantation would improve their health than whites (12). However, among patients who wanted a transplant, black patients remained less likely than white patients to be referred for evaluation, be placed on a waiting list, and receive a transplant within 18 months after the start of dialysis. A study of physician-related factors found that physicians were less likely to believe that transplantation improves survival for black than white patients (14).

Until recently, there has been no source of national data that could be used to determine whether there are any disparities in the rate or timing of nephrologists’ assessment of patients for their transplant suitability and potential referral for formal transplant evaluation. However, in 2005, the Medical Evidence Report (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services [CMS] Form CMS-2728) was modified to record information about whether incident dialysis patients were informed of kidney transplant options. We examined the extent to which report of not informed about transplant options because not assessed on Form CMS-2728 was associated with patient race, ethnicity, and insurance status. We focused our analyses on nonassessment as the reason for not being informed about transplant options, because universal early assessment is theoretically possible and would be a key step to achieving the Healthy People 2020 goal “to increase the proportion of dialysis patients waitlisted and/or receiving a deceased donor kidney transplant within 1 year of ESRD start (among patients under 70 years of age)” (15). We hypothesized that there would be differences in reported nonassessment based on race, ethnicity, and insurance. We also hypothesized that being reported as not having been assessed for transplant around the time of dialysis initiation would be associated with lower likelihood of waitlisting for transplantation and receipt of a kidney transplant.

Materials and Methods

Study Subjects and Data Sources

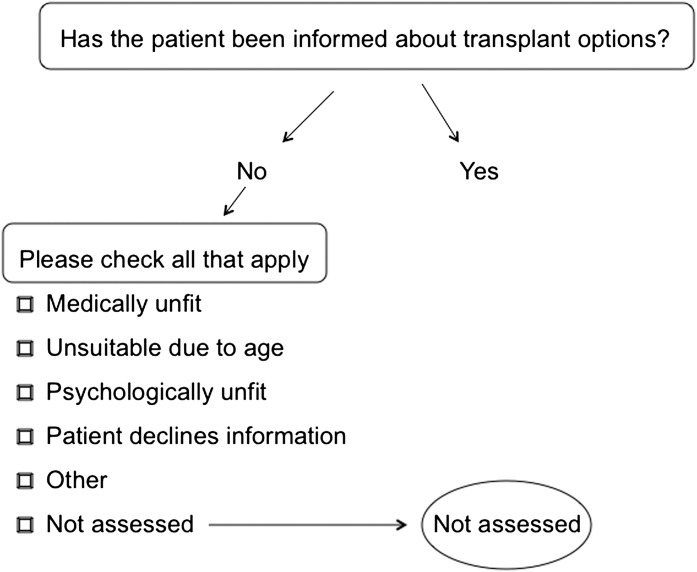

Data were abstracted from the US Renal Data System MEDEVID05 and Waitlist Standard Analysis Files. Completion of Form CMS-2728 by the chronic dialysis facility is required when a patient receives his or her first outpatient dialysis treatment. Since June of 2005, the form has included a question that asks, “Has patient been informed of kidney transplant options?” In addition, for patients who have not been informed about transplant options, Form CMS-2728 requests all applicable reasons from the following list: patient declines information, medically unfit, psychologically unfit, patient has not been assessed, unsuitable because of age, and other. We focused our analyses on reported nonassessment. There has been no specific validation of these Form 2728 kidney transplant items, and there may be variability in the personnel providing data and the accuracy of the information. We adopted the conservative strategy of comparing patients who were reported as not assessed with patients reported informed of transplant options and patients reported not informed for a reason other than not assessed (Figure 1). Black or white patients ages 18 years and older who started dialysis from January of 2005 to September of 2009 were identified (n=449,518). Patients whose 2728 forms were not completed within 2 months of starting dialysis were excluded (n=21,547), because our hypotheses concerned assessment for transplantation around the time of dialysis initiation rather than at a later date. In addition, 1482 patients reported as both not assessed and having a specific reason for not being informed about transplant were excluded, because it was unclear whether they had or had not been assessed. The analytic cohort, thus, contained 426,489 patients.

Figure 1.

Diagram of determination of which patients were not assessed for transplantation. Text inside the rectangles indicates the questions on Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Form 2728.

Data on predictor variables and covariates were also based on information from the 2728 form, including sex, race, ethnicity, type of insurance (private, Medicaid, Medicare, none, or other), employment status (employed or student versus other), dialysis modality, current smoking, body mass index (kg/m2), comorbidity (alcohol dependence, amputation, atherosclerotic heart disease, congestive heart failure, history of cerebrovascular accident or transient ischemic attack, diabetes, drug dependence, hypertension, other cardiac disorder, or peripheral vascular disease), functional status (inability to walk, inability to transfer, or need for assistance with activities of daily living), whether institutionalized, early nephrology care (seen by a nephrologist before starting dialysis), and region of the country. Thus, race and ethnicity were according to the provider report.

Statistical Methods

Patients in the study cohort were stratified into five age categories for analyses: 18–34, 35–49, 50–64, 65–79, and 80 years and older. We performed logistic regression analysis for each of the five age categories with whether the patient was reported as not assessed for transplantation as the outcome variable, accounting for race, ethnicity, and insurance type as covariates.

Cox proportional hazards models were estimated to examine the association of nonassessment with placement on the waiting list and kidney transplantation, with censoring at death or the end of study follow-up (September 30, 2009). Patients who had been preemptively waitlisted were assigned a value of 0 time to waitlisting. For these analyses, patients were split into three categories: those patients who were not informed of transplant options because of unsuitability, those patients who were not informed because they were not assessed, and those patients who were informed.

We hypothesized that patients who were informed about transplantation would be more likely to be waitlisted and subsequently transplanted than those patients not assessed. Conversely, those patients not informed for a reason other than nonassessment would be less likely to be waitlisted or transplanted than those patients who had not yet been assessed, because some patients who are initially not assessed may eventually be assessed and found to be suitable candidates. All potential explanatory variables were included in the models. Patients with missing data for covariates (19%) were excluded. These patients did not differ substantially from the patients included in the analyses. On completion of these models, we determined that the proportional hazards assumption was violated for our predictor variable (assessment). We, therefore, generated separate models for 1, 2, 3, and ≥4 years after dialysis initiation.

Results

Characteristics of the study population are as reported in Table 1. Briefly, the median age (interquartile range) was 65 (53–75) years, 56% were male, 30% were black, and 53% had diabetes. There were small differences in the characteristics of patients reported as not assessed and others, but as expected, there was no clear pattern of sicker patients not being assessed. Overall, 12.5% of patients were reported not to have been assessed for transplantation around the time of initiating dialysis. In the younger age categories (less than age 65 years), nonassessment was more common than being reported not suitable for kidney transplantation. However, specific reasons were cited more often in the older age categories (unsuitable because of age and medically unfit being most common). Table 2 shows the racial, ethnic, insurance, and early nephrology care characteristics of the patients reported as not assessed by age category. The percentages of black, Hispanic, and uninsured patients were higher among the younger age groups, and the percentage who received nephrology care before dialysis was lower among younger patients.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics by nonassessment status

| Variable | Not Informed of Transplant Options Because Not Assessed (n=53,205) | Informed of Transplant Options or Not Informed for a Reason Other Than Not Assessed (n=373,284) |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years (mean [SD]) | 62.6 (14.2) | 63.3 (15.4) |

| Male sex (%) | 56.1 | 56.0 |

| Black race (%) | 31.8 | 30.0 |

| Hispanic ethnicity (%) | 13.7 | 13.8 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | ||

| <20 | 7.7 | 7.9 |

| 20–25 | 26.6 | 27.6 |

| 25–30 | 28.3 | 28.7 |

| ≥30 | 37.5 | 35.8 |

| Hemodialysis (%) | 97.7 | 93.4 |

| Comorbidity (%) | ||

| diabetes | 56.3 | 53.0 |

| hypertension | 84.0 | 84.6 |

| atherosclerotic heart disease | 18.7 | 22.2 |

| congestive heart failure | 32.9 | 33.3 |

| other cardiac conditions | 16.7 | 16.2 |

| peripheral vascular disease | 13.4 | 14.5 |

| amputation | 3.4 | 3.1 |

| CVA or TIA | 9.2 | 9.7 |

| Habits (%) | ||

| alcohol dependence | 2.0 | 1.6 |

| drug dependence | 1.7 | 1.4 |

| tobacco use | 7.6 | 6.2 |

| Functional status (%) | ||

| inability to ambulate | 6.0 | 6.8 |

| inability to transfer | 2.6 | 3.3 |

| needs assistance in daily activities | 10.1 | 11.2 |

| institutionalized | 7.2 | 7.6 |

| Employed or student (%) | 8.3 | 11.3 |

| Insurance (%) | ||

| private | 21.6 | 25.9 |

| Medicare | 48.3 | 47.8 |

| Medicaid | 12.8 | 11.0 |

| other | 8.3 | 7.9 |

| none | 9.1 | 7.4 |

| Nephrology care before dialysis | 59.1 | 66.0 |

CVA, cerebrovascular accident; TIA, transient ischemic attack. P values for all variables by assessment categories are <0.001 except 0.77 (male sex), 0.30 (Hispanic ethnicity), 0.07 (congestive heart failure), 0.003 (other cardiac conditions), and 0.003 (institutionalized).

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients reported not assessed for transplantation by age category

| Age (years) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤18 to <35 (n=1978) | 35 to <50 (n=6753) | 50 to <65 (n=17,142) | 65 to <80 (n=18,822) | ≥80 (n=5598) | |

| Black (%) | 49.7 | 47.2 | 36.4 | 24.7 | 16.7 |

| Hispanic (%) | 21.9 | 16.5 | 15.6 | 11.7 | 7.6 |

| Insurance (%) | |||||

| Medicaid | 31.0 | 26.6 | 19.6 | 2.8 | 1.5 |

| Medicare | 9.0 | 17.8 | 27.6 | 73.8 | 77.9 |

| none | 28.4 | 22.2 | 12.9 | 1.2 | 0.6 |

| other | 10.1 | 9.1 | 11.5 | 5.4 | 5.8 |

| private | 21.5 | 24.3 | 28.3 | 16.8 | 14.2 |

| Nephrology care before dialysis (%) | 41.2 | 49.5 | 57.8 | 64.6 | 62.9 |

In univariate analysis, black patients were 5% more likely to be reported as not assessed (odds ratio [OR]=1.05, 95% confidence interval [CI]=1.03–1.08), but Hispanic patients were not more likely (OR=0.99, 95% CI=0.96–1.01). The disparity among black individuals was related, in part, to insurance status, and it was not uniform across the age spectrum. Table 3 and Supplemental Table 1 show the multivariable odds ratios of being not assessed for transplantation for black race, Hispanic ethnicity, insurance status, and whether the patients received early nephrology care across age categories. The overall OR for black race was 1.05 (95% CI=1.04–1.07), but significant differences were seen only in the younger age groups (e.g., 1.27, 95% CI=1.13–1.43 for ages 18–35 years; P<0.001 for interaction between race and age). Overall, Hispanic patients were less likely to be reported as not assessed (OR=0.94, 95% CI=0.91–0.97), but this finding was not the case for the youngest group of Hispanic patients (OR=1.08, 95% CI=0.93–1.24; P<0.001 for interaction between ethnicity and age). Insurance status was strongly associated with the odds of not being assessed for transplantation after adjusting for race and ethnicity, with patients with Medicare, Medicaid, other insurance, and no insurance at a substantial disadvantage compared with privately insured individuals, particularly among younger patients. Having no insurance was particularly disadvantageous, with OR=1.51 (95% CI=1.30–1.75) and OR=1.62 (95% CI=1.49–1.76) for not being assessed among patients 18–34 and 35–49 years, respectively. Of note, disparities based on black race and nonprivate insurance persisted among the youngest patients even after adjustment for whether patients had been seen by a nephrologist before starting dialysis.

Table 3.

Odds ratios for being reported not assessed for transplantation

| Age (years) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Ages (n=355,738) | ≤18 to <35 (n=16,794) | 35 to <50 (n=49,402) | 50 to <65 (n=111,280) | 65 to <80 (n=124,842) | ≥80 (n=43,420) | |

| Black race | 1.05 (1.02, 1.07) | 1.27 (1.13, 1.43) | 1.02 (0.96, 1.09) | 1.00 (0.97, 1.04) | 1.02 (0.98, 1.06) | 0.99 (0.91, 1.08) |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 0.94 (0.91, 0.97) | 1.08 (0.93, 1.24) | 0.88 (0.81, 0.96) | 0.90 (0.86, 0.95) | 0.93 (0.88, 0.98) | 0.99 (0.88, 1.12) |

| Insurance | ||||||

| private (reference) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Medicare | 1.21 (1.18, 1.24) | 1.38 (1.13, 1.70) | 1.58 (1.45, 1.73) | 1.36 (1.30, 1.43) | 1.11 (1.06, 1.16) | 1.05 (0.96, 1.14) |

| other | 1.23 (1.18, 1.28) | 1.37 (1.11, 1.68) | 1.31 (1.17, 1.47) | 1.25 (1.17, 1.33) | 1.16 (1.06, 1.26) | 1.10 (0.94, 1.28) |

| Medicaid | 1.33 (1.28, 1.38) | 1.39 (1.20, 1.61) | 1.55 (1.43, 1.67) | 1.39 (1.32, 1.47) | 1.16 (1.03, 1.31) | 1.09 (0.80, 1.47) |

| none | 1.38 (1.33, 1.44) | 1.51 (1.30, 1.75) | 1.62 (1.49, 1.76) | 1.42 (1.34, 1.51) | 1.18 (1.00, 1.39) | 1.03 (0.67, 1.59) |

| Nephrology care before dialysis | 0.77 (0.75, 0.78) | 0.62 (0.56, 0.69) | 0.67 (0.64, 0.71) | 0.73 (0.70, 0.75) | 0.81 (0.78, 0.84) | 0.86 (0.81, 0.92) |

Results are reported as odds ratio (95% confidence interval); n=355,738 with complete data for all variables.

Overall, 10% of patients were waitlisted within 1 year (29% of patients ages 18 to <35 years), and 14.3% of patients were waitlisted by the end of follow-up. After 1 year, 1.8% of patients had received a kidney transplant, and by the end of the follow-up, 4.4% of patients had been transplanted. Cox proportional hazards modeling was performed to estimate the likelihood (hazard) of waitlisting and transplantation among patients not assessed for transplantation around dialysis initiation after adjustment for other potential predictors of waitlisting. As we hypothesized, the hazard ratios (HRs) for waitlisting and transplantation were lowest for the patients who were reported not informed about transplant, because they were not suitable (HR=0.28, 95% CI=0.26–0.30 for waitlisting and HR=0.26 and 95% CI=0.22–0.29 for transplantation), and also, HRs were significantly lower among patients who were reported as not assessed compared with those patients who were informed about transplant options (HR=0.68, 95% CI=0.66–0.71 for waitlisting and HR=0.61, 95% CI=0.57–0.65 for transplantation). However, the models violated the proportional hazards assumptions for several key predictor variables, including assessment and race, and therefore, we constructed separate models by year (Tables 4 and 5). For waitlisting, the associations of nonassessment with delay were stronger in the first year and became weaker over time (Table 4). In fact, beyond year 4, there was no longer a lower hazard of waitlisting among those patients who were reported as not assessed around dialysis initiation. Black race and nonprivate insurance were associated with lower chance of waitlisting in the first 2 years after adjusting for clinical and demographic factors as well as whether patients had been seen by a nephrologist before starting dialysis. Hispanic ethnicity was not associated with likelihood of waitlisting in the first year but was associated with increased likelihood thereafter. For transplantation, similar patterns emerged for assessment, race, and insurance status, except that the significant differences persisted for the entire follow-up period (Table 5). Unlike for waitlisting, Hispanic patients were less likely to be transplanted after adjustment for the other factors.

Table 4.

Multivariable adjusted hazard ratios for transplant waitlisting by year since starting dialysis

| Variable | Year 1 (Hazard Ratio) | Year 2 (Hazard Ratio) | Year 3 (Hazard Ratio) | Year 4+ (Hazard Ratio) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Informed about transplant options | ||||

| informed (reference) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| not informed because not assessed | 0.59 (0.57, 0.62) | 0.89 (0.84, 0.94) | 0.77 (0.69, 0.86) | 1.15 (0.95, 1.39) |

| not informed for other reasons | 0.21 (0.20, 0.23) | 0.40 (0.36, 0.45) | 0.43 (0.35, 0.52) | 0.57 (0.41, 0.81) |

| Age category (years) | ||||

| 18 to <35 (referent) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 35 to <50 | 0.73 (0.71, 0.76) | 0.79 (0.74, 0.85) | 0.82 (0.72, 0.93) | 0.85 (0.68, 1.07) |

| 50 to <65 | 0.53 (0.51, 0.55) | 0.57 (0.53, 0.61) | 0.60 (0.53, 0.68) | 0.56 (0.45, 0.71) |

| 65 to <80 | 0.21 (0.20, 0.22) | 0.20 (0.18, 0.22) | 0.18 (0.15, 0.21) | 0.15 (0.11, 0.20) |

| ≥80 | 0.01 (0.007, 0.01) | 0.01 (0.007, 0.01) | 0.01 (0.33, 0.02) | 0.01 (0.001, 0.04) |

| Male sex | 1.13 (1.11, 1.16) | 1.20 (1.16, 1.25) | 1.17 (1.08, 1.26) | 1.21 (1.05, 1.39) |

| Black race | 0.71 (0.69, 0.73) | 0.92 (0.88, 0.96) | 1.06 (0.97, 1.15) | 1.12 (0.96, 1.31) |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 0.98 (0.95, 1.01) | 1.20 (1.13, 1.27) | 1.52 (1.38, 1.69) | 1.34 (1.10, 1.63) |

| Hemodialysis (versus peritoneal dialysis) | 0.68 (0.66, 0.69) | 0.82 (0.77, 0.87) | 0.77 (0.68, 0.86) | 0.74 (0.59, 0.91) |

| Diabetes | 0.65 (0.64, 0.67) | 0.89 (0.86, 0.93) | 0.97 (0.90, 1.05) | 0.95 (0.83, 1.10) |

| Employed or student | 1.52 (1.48, 1.56) | 1.39 (1.32, 1.46) | 1.35 (1.23, 1.48) | 1.44 (1.21, 1.71) |

| Insurance | ||||

| private (reference) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Medicare | 0.63 (0.61, 0.65) | 0.66 (0.62, 0.70) | 0.69 (0.62, 0.77) | 0.66 (0.53, 0.80) |

| Medicaid | 0.52 (0.50, 0.54) | 0.61 (0.57, 0.65) | 0.67 (0.60, 0.75) | 0.63 (0.51, 0.79) |

| other | 0.77 (0.74, 0.80) | 0.88 (0.82, 0.94) | 0.90 (0.79, 1.02) | 0.92 (0.72, 1.17) |

| none | 0.42 (0.41, 0.44) | 0.80 (0.75, 0.85) | 0.84 (0.75, 0.94) | 0.77 (0.62, 0.95) |

| Nephrology care before dialysis | 2.12 (2.06, 2.17) | 1.40 (1.34, 1.46) | 1.42 (1.31, 1.54) | 1.51 (1.30, 1.76) |

Results are reported as hazard ratio (95% confidence interval); n=345,266 with complete data for all variables. Model also adjusted for sex, race, ethnicity, type of insurance (private, Medicaid, Medicare, none, or other), employment status (employed or student versus other), current smoking, body mass index (kg/m2), other comorbidities (alcohol dependence, amputation, atherosclerotic heart disease, congestive heart failure, history of cerebrovascular accident or transient ischemic attack, drug dependence, hypertension, other cardiac disorder, or peripheral vascular disease), functional status (inability to walk, inability to transfer, or need for assistance with activities of daily living), whether institutionalized, nephrology care before dialysis, and region of the country.

Table 5.

Multivariable adjusted hazard ratios for transplantation by year since starting dialysis

| Variable | Year 1 (Hazard Ratio) | Year 2 (Hazard Ratio) | Year 3 (Hazard Ratio) | Year 4+ (Hazard Ratio) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Informed about transplant options | ||||

| informed (reference) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| not informed because not assessed | 0.46 (0.41, 0.51) | 0.66 (0.59, 0.73) | 0.78 (0.68, 0.89) | 0.75 (0.61, 0.94) |

| not informed for other reasons | 0.20 (0.16, 0.25) | 0.26 (0.21, 0.33) | 0.29 (0.22, 0.38) | 0.45 (0.31, 0.65) |

| Age category (years) | ||||

| 18 to <35 (referent) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 35 to <50 | 0.55 (0.51, 0.59) | 0.63 (0.58, 0.68) | 0.68 (0.60, 0.77) | 0.79 (0.66, 0.96) |

| 50 to <65 | 0.33 (0.30, 0.35) | 0.40 (0.37, 0.43) | 0.51 (0.45, 0.57) | 0.55 (0.45, 0.67) |

| 65 to <80 | 0.13 (0.11, 0.14) | 0.18 (0.17, 0.21) | 0.19 (0.17, 0.23) | 0.22 (0.17, 0.29) |

| ≥80 | 0.01 (0.004, 0.01) | 0.01 (0.005, 0.02) | 0.002 (0.0, 0.01) | 0.00 (0.0a) |

| Male sex | 1.10 (1.04, 1.15) | 1.20 (1.13, 1.27) | 1.23 (1.14, 1.33) | 1.29 (1.14, 1.47) |

| Black race | 0.29 (0.27, 0.31) | 0.41 (0.39, 0.44) | 0.55 (0.50, 0.60) | 0.61 (0.53, 0.70) |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 0.59 (0.54, 0.64) | 0.67 (0.61, 0.73) | 0.82 (0.73, 0.92) | 0.79 (0.65, 0.95) |

| Hemodialysis (versus peritoneal dialysis) | 0.92 (0.86, 0.98) | 0.75 (0.70, 0.81) | 0.75 (0.68, 0.83) | 0.72 (0.61, 0.86) |

| Diabetes | 0.69 (0.66, 0.73) | 0.84 (0.79, 0.89) | 0.85 (0.78, 0.92) | 0.74 (0.65, 0.85) |

| Employed or student | 1.64 (1.55, 1.74) | 1.57 (1.48, 1.68) | 1.45 (1.32, 1.58) | 1.41 (1.22, 1.62) |

| Insurance | ||||

| private (reference) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Medicare | 0.53 (0.49, 0.58) | 0.62 (0.57, 0.67) | 0.68 (0.60, 0.76) | 0.61 (0.51, 0.75) |

| Medicaid | 0.40 (0.36, 0.44) | 0.49 (0.45, 0.55) | 0.57 (0.49, 0.65) | 0.60 (0.49, 0.74) |

| other | 0.78 (0.72, 0.85) | 0.82 (0.78, 0.90) | 0.95 (0.84, 1.08) | 1.05 (0.85, 1.28) |

| none | 0.30 (0.26, 0.34) | 0.57 (0.52, 0.63) | 0.67 (0.59, 0.76) | 0.66 (0.54, 0.82) |

| Nephrology care before dialysis | 2.31 (2.16, 2.48) | 1.68 (1.57, 1.80) | 1.78 (1.62, 1.95) | 1.52 (1.32, 1.76) |

Results are reported as hazard ratio (95% confidence interval); n=345,266 with complete data for all variables. Model also adjusted for sex, race, ethnicity, type of insurance (private, Medicaid, Medicare, none, or other), employment status (employed or student versus other), current smoking, body mass index (kg/m2), other comorbidities (alcohol dependence, amputation, atherosclerotic heart disease, congestive heart failure, history of cerebrovascular accident or transient ischemic attack, drug dependence, hypertension, other cardiac disorder, or peripheral vascular disease), functional status (inability to walk, inability to transfer, or need for assistance with activities of daily living), whether institutionalized, nephrology care before dialysis, and region of the country.

Large standard error results in large upper bound.

Discussion

We found that 12.5% of patients starting dialysis in 2005–2009 had reportedly not been assessed for transplantation. This group is particularly worthy of scrutiny, because unlike older age or medical unsuitability, lack of assessment is potentially addressable. All patients should be assessed for transplantation and have transplant options discussed if there are no contraindications. Furthermore, our analyses showed that not being assessed was associated with reduced likelihood of being placed on the waiting list or receiving a transplant.

A recent analysis in the article by Kucirka et al. (16) reported a 53% lower relative rate of waitlisting among patients reported not to be informed of transplant options. Our focus on patients reported not to be assessed complements their findings and highlights additional disparities. Specifically, black race was associated with decreased likelihood of assessment for transplantation around the time of dialysis initiation even after adjustment for insurance type, particularly among younger patients. Hispanic ethnicity was associated with lower rates of nonassessment among older patients after adjustment for type of insurance. Insurance status was strongly associated with transplant assessment, with privately insured patients substantially less likely to be not assessed. Lack of assessment for transplantation around the time of dialysis initiation was associated with decreased likelihood of transplant waitlisting, particularly in the first 2 years of follow-up, and lower chance of transplantation over up to 5 years of follow-up after adjusting for other factors, including race, ethnicity, insurance status, and medical factors. Although limited access to care is a logical potential contributor to lower rates of transplant assessment and waitlisting among minority and underinsured patients, the associations of race and insurance with transplant assessment and waitlisting for a transplant were independent of type of insurance and whether the patient was seen by a nephrologist before dialysis initiation. Interestingly, older Hispanic patients were less likely than non-Hispanic patients to be reported not assessed for transplant after adjustment for insurance status and predialysis nephrology care, suggesting that perhaps access to care is an important driving factor of disparities among Hispanic individuals.

The disparities that we observed primarily affected younger patients, for whom early referral may be the most important, because younger patients’ life expectancy may be increased to a greater extent than older patients’ life expectancy by receipt of a kidney transplant (1). These disparities in reported assessment may be important not because they explain the overall disparities in transplantation based on race and income but because their contribution to delayed transplantation could be addressed through policy interventions. One such intervention was implemented in January of 2010, when a new Medicare benefit was added for patients with stage 4 CKD that reimburses healthcare providers for education about treatment choices for ESRD, including transplantation. Other policy changes are under consideration to increase the rate of timely assessment and referral for formal transplant evaluation or mitigate the effects of any delays in assessment and referral. CMS is developing an ESRD Quality Incentive Program, under which reimbursement for dialysis centers will be partly based on how those centers achieve certain performance goals, with implementation slated for January of 2012. Although transplant assessment is not among the currently proposed quality metrics, the United Network for Organ Sharing Kidney Transplant Committee is considering the possibility of recommending the inclusion of a standard based on appropriate referral for kidney transplantation in an effort to achieve more uniform, earlier assessment and referral from dialysis facilities. Changes in the allocation of available cadaveric kidneys for transplantation are also being considered. Currently, patients’ waiting time, a major determinant of priority for transplantation, begins at the time of placement on the waiting list by a transplant center. United Network for Organ Sharing has been considering a proposal that includes changing the time of waiting to start at the time of dialysis initiation rather than the time of placement on the waiting list. Such a change would not be likely to increase timely assessment by dialysis centers, but it would eliminate delays in transplantation related to delayed assessment and referral. Our results suggest that such a change in waiting time calculation would help to mitigate disparities based on race and insurance type.

A strength of this study is that all black and white patients starting dialysis and not previously transplanted in the study period were included, resulting in a large sample size and data that reflect practice in the whole of the United States. A limitation of our study is that information about whether patients were assessed for transplantation was collected only from providers’ point of view and could be susceptible to inflation. Furthermore, it is likely that there is variability surrounding which members of the dialysis healthcare team actually complete this portion of the Medical Evidence Report. Although our analysis strategy might result in misclassifying some nonassessed patients as assessed, the alternative misclassification is unlikely. We expect that the number of patients who were not assessed was underestimated. A third limitation is the lack of information about the quality of information conveyed to patients when discussion did take place or patients’ perceptions and level of comprehension of the risks and benefits of transplantation. However, Form 2728 provides no specific criteria for what constitutes informing patients about transplant options, and the level of assessment that occurs when a reason for unsuitability is provided remains unknown. Thus, although a 12.5% rate of nonassessment could be viewed by some as acceptable, there may have been a tendency for providers to overreport that patients were informed of kidney transplant options. Furthermore, not being assessed was associated with lower likelihood of waitlisting for transplantation, suggesting that no patient should go unassessed within 60 days of dialysis initiation.

In conclusion, there is considerable room for improvement in assessment of patients for transplantation, because providers reported that 12.5% of patients had not been assessed for suitability for referral for transplantation at the time of completion of the Medical Evidence Report after dialysis initiation. Racial and insurance-related disparities in transplant assessment were evident among the youngest patients, potentially delaying referral for formal transplant evaluation among patients who may stand to benefit the most from transplantation. New Medicare benefits have been introduced in an effort to address the deficits in discussion of ESRD treatment options. The extent to which these benefits increase overall levels and quality of pre-ESRD discussion of treatment options and mitigate existing racial and insurance-related disparities should be systematically evaluated.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of support were National Institutes of Health Contract HHSN267200715004C and NIH Administrative Database Contract N01-DK-7-5004.

The interpretation and reporting of the data presented here are the responsibility of the authors and in no way should be seen as an official policy or interpretation of the US government.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.13151211/-/DCSupplemental.

See related editorial, “Reducing Disparities in Assessment for Kidney Transplantation,” on pages 1378–1381.

References

- 1.United States Renal Data System : USRDS Annual Data Report. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease, Bethesda, MD, National Institutes of Health, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolfe RA, Ashby VB, Milford EL, Ojo AO, Ettenger RE, Agodoa LY, Held PJ, Port FK: Comparison of mortality in all patients on dialysis, patients on dialysis awaiting transplantation, and recipients of a first cadaveric transplant. N Engl J Med 341: 1725–1730, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Evans RW, Manninen DL, Garrison LP, Jr, Hart LG, Blagg CR, Gutman RA, Hull AR, Lowrie EG: The quality of life of patients with end-stage renal disease. N Engl J Med 312: 553–559, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Epstein AM, Ayanian JZ, Keogh JH, Noonan SJ, Armistead N, Cleary PD, Weissman JS, David-Kasdan JA, Carlson D, Fuller J, Marsh D, Conti RM: Racial disparities in access to renal transplantation—clinically appropriate or due to underuse or overuse? N Engl J Med 343: 1537–1544, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolfe RA, Ashby VB, Milford EL, Bloembergen WE, Agodoa LY, Held PJ, Port FK: Differences in access to cadaveric renal transplantation in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis 36: 1025–1033, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alexander GC, Sehgal AR: Barriers to cadaveric renal transplantation among blacks, women, and the poor. JAMA 280: 1148–1152, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Satayathum S, Pisoni RL, McCullough KP, Merion RM, Wikström B, Levin N, Chen K, Wolfe RA, Goodkin DA, Piera L, Asano Y, Kurokawa K, Fukuhara S, Held PJ, Port FK: Kidney transplantation and wait-listing rates from the international Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). Kidney Int 68: 330–337, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stolzmann KL, Bautista LE, Gangnon RE, McElroy JA, Becker BN, Remington PL: Trends in kidney transplantation rates and disparities. J Natl Med Assoc 99: 923–932, 2007 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keith D, Ashby VB, Port FK, Leichtman AB: Insurance type and minority status associated with large disparities in prelisting dialysis among candidates for kidney transplantation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 3: 463–470, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alexander GC, Sehgal AR: Why hemodialysis patients fail to complete the transplantation process. Am J Kidney Dis 37: 321–328, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patzer RE, Perryman JP, Schrager JD, Pastan S, Amaral S, Gazmararian JA, Klein M, Kutner N, McClellan WM: The role of race and poverty on steps to kidney transplantation in the southeastern United States. Am J Transplant 12: 358–368, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ayanian JZ, Cleary PD, Weissman JS, Epstein AM: The effect of patients’ preferences on racial differences in access to renal transplantation. N Engl J Med 341: 1661–1669, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boulware LE, Meoni LA, Fink NE, Parekh RS, Kao WH, Klag MJ, Powe NR: Preferences, knowledge, communication and patient-physician discussion of living kidney transplantation in African American families. Am J Transplant 5: 1503–1512, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ayanian JZ, Cleary PD, Keogh JH, Noonan SJ, David-Kasdan JA, Epstein AM: Physicians’ beliefs about racial differences in referral for renal transplantation. Am J Kidney Dis 43: 350–357, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.US Department of Health and Human Services : 2020 Topics and Objectives. HealthyPeople.gov, US Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, DC, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kucirka LM, Grams ME, Balhara KS, Jaar BG, Segev DL: Disparities in provision of transplant information affect access to kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant 12: 351–357, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.