Abstract

Microbial pathogens utilize complex secretion systems to deliver proteins into host cells. These effector proteins target and usurp host cell processes to promote infection and cause disease. While secretion systems are conserved, each pathogen delivers its own unique set of effectors. The identification and characterization of these effector proteins has been difficult, often limited by the lack of detectable signal sequences and functional redundancy. Model systems including yeast, worms, flies, and fish are being used to circumvent these issues. This technical review details the versatility and utility of yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae as a system to identify and characterize bacterial effectors.

The Awesome Power of Yeast Genetics and Genomics

There are many advantages to working with the yeast, S. cerevisiae. It is easy to grow in the laboratory, genetically tractable, and has been used as a model system for studying eukaryotic cellular processes for over 50 years. These studies have provided insights into fundamental eukaryotic processes, including transcription, translation, RNA processing, cell signaling, cytoskeletal dynamics, and vesicle trafficking. Presently, over 75% of yeast ORFs have known or predicted functions, and much of this information is easily accessible in a variety of databases on the world wide web (see Table 1 for a listing of the sites).

Table 1.

Useful Databases and Resources

| Saccharomyces Genome Database (SGD) | http://www.yeastgenome.org | SGD is an organized collection of genetic and molecular biological information about annotated yeast ORFs |

| The Yeast Proteome Database (YPD) | https://www.proteome.com/proteome | This is a commercial comprehensive database of information regarding annotated yeast ORFs |

| Comprehensive Yeast Genome Database (CYGD-MIPS) |

http://mips.gsf.de/genre/proj/yeast/index.jsp | CYGD presents information on the molecular structure and functional network of S. cerevisiae |

| Biomolecular Interaction Network Database (BIND) |

http://bind.ca | BIND is a database designed to store full descriptions of interactions, molecular complexes and pathways |

| Yeast GFP Fusion Localization Database | http://yeastgfp.ucsf.edu | This database is a repository for localization of GFP fusion proteins in yeast |

| Yeast Protein Localization Database (YPL) | http://ypl.uni-graz.at/pages/home.html | This database is a repository for global analyses of localization studies in yeast |

| Virtual Library—Yeast | http://www.yeastgenome.org/VL-yeast.html | Source for general information regarding yeast as an experimental model |

| Open Biosystems |

http://www.openbiosystems.com/ GeneExpression/Yeast |

Commercial source for yeast deletion and overexpressor strain collections |

| Euroscarf: European Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Archive for Functional Analyses |

http://web.uni-frankfurt.de/fb15/mikro/euroscarf/index.html | Source of yeast deletion stains as well as other useful yeast strains and expression plasmids |

| Invitrogen | http://clones.invitrogen.com/cloneinfo.php?clone=yeastgfp | Commercial source for both yeast deletion strain and yeast GFP clone collections |

Many tools and resources are available for designing and executing both genome-wide (discovery-driven) and smaller-scale (hypothesis-driven) experiments. In addition to comprehensive yeast DNA (DeRisi et al., 1997) and protein microarrays (Zhu et al., 2000), several isogenic strain collections are available where each strain carries a genetically altered version of one of the ~6200 annotated ORFs. These alterations include targeted gene deletions for use in phenotypic assays (Giaever et al., 2002), fusions of each ORF to GFP for subcellular localization studies (Huh et al., 2003), tandem affinity tags for protein expression and coimmunoprecipitation assays (Ghaemmaghami et al., 2003), and fusions to the GAL4-binding domain for two-hybrid assays (Uetz et al., 2000). Strain collections that conditionally overexpress each of the annotated yeast ORFs also exist (Gelperin et al., 2005; Sopko et al., 2006).

The utilization of yeast in the study of pathogenic microbes relies on the observation that bacterial effector proteins often target eukaryotic cellular processes conserved between yeast and mammals. Currently, Agrobacterium tumefaciens, a plant pathogen, is the only pathogen known to be capable of delivering proteins directly through the yeast cell wall into the cytoplasm via its specialized type IV secretion system (Piers et al., 1996). Thus, rather than studying effector proteins in the context of an infection, individual effector proteins are expressed de novo in yeast. For this reason, the yeast system is particularly applicable for studying proteins thought to act within host cells. In addition, since this system only requires DNA, it provides a valuable resource for studying effector proteins from pathogens that are difficult to grow or genetically manipulate. Expression of effector proteins can lead to a variety of discernable phenotypes in yeast (discussed below) that can lead to testable hypotheses regarding their functions and/or their roles in pathogenesis. Once generated, hypotheses can be pursued in yeast as well as in physiologic models of disease.

Expression of Bacterial Effector Proteins in Yeast

There is increasing evidence that yeast growth inhibition due to the expression of bacterial proteins is a sensitive and specific indicator of the activity of effector proteins that perturb conserved cellular processes. Effector proteins from both plant and animal pathogens–including Pseudomonas syringae (Munkvold et al., 2008), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Rabin and Hauser, 2003; Sato et al., 2003; Stirling and Evans, 2006), Shigella flexneri (Alto et al., 2006; Slagowski et al., 2008), Salmonella typhimurium (Aleman et al., 2005; Lesser and Miller, 2001; Rodriguez-Pachon et al., 2002), Legionella pneumophila (Campodonico et al., 2005; Derre and Isberg, 2005), Chlamydia trachomatis (Sisko et al., 2006), enteropathogenic E. coli (Hardwidge et al., 2005; Rodriguez-Escudero et al., 2005), and Yersinia species (Lesser and Miller, 2001; Nejedlik et al., 2004; Von Pawel-Rammingen et al., 2000)–have been observed to inhibit growth when expressed in yeast. In contrast, expression of very few nontranslocated proteins affects yeast growth (Campodonico et al., 2005; Slagowski et al., 2008).

Since a priori it is not known whether expression of the proteins will be toxic to yeast, it is best to first express an effector protein under the control of an inducible promotor. This is most commonly accomplished by use of the GAL1/10 promotor, a strong promotor whose activity is regulated by the carbon source in the media. However, this promotor is slightly leaky under repressing conditions, and expression of extremely toxic effector proteins can be difficult in this system (Slagowski et al., 2008; Stirling and Evans, 2006). Alternatively, effector proteins can be placed under the control of the weaker MET3 (Von Pawel-Rammingen et al., 2000) and CUP1 (Arnoldo et al., 2008) promotors. In these cases, expression is controlled by the presence of methionine or copper in the media, respectively. Another option is the tightly controlled tetracycline-responsive tetO promotor (Belli et al., 1998; Skrzypek et al., 2003). This is not an endogenous yeast promotor, and modified yeast strains that encode a tetR repressor must be used to tightly control expression.

The copy number of the genes encoding the effector proteins will also influence protein levels in yeast. It is easiest to either encode the effector protein on centromere-containing (copy number 1–3) or 2 micron (copy number 40–60) plasmids, although targeted homologous recombination can be used to introduce a single copy of a gene into the yeast genome. Studies with Shigella effector proteins suggest that the sensitivity and specificity of growth inhibition as an indicator of effector proteins is optimized when the proteins are expressed from low copy-number plasmids (Slagowski et al., 2008). However, it is possible that effector proteins from other pathogens will not be as well expressed in yeast, and in these cases it might prove fruitful to express the effector proteins from high copy-number plasmids.

Another variable to consider when expressing effector proteins in yeast is the addition of an epitope tag. Evidence exists that fusion of effector proteins to GFP can influence growth inhibition due to their expression (Slagowski et al., 2008). In the majority of cases, fusion to GFP results in increased growth inhibition, presumably due to increased expression and/or stability of the effector proteins (March et al., 2003). However, there are also examples of where fusion to GFP decreased toxicity of the effector proteins, presumably due to steric interference. If the location of the secretion signal of the effector protein is known, fusing to GFP to this domain is presumably less likely to interfere with the activity of the effector protein, since this domain is thought to be unstructured.

There are numerous options available for monitoring yeast growth inhibition due to expression of an effector protein. One relatively simple assay for detecting qualitative differences in growth is to plate serial dilutions of saturated yeast cultures on inducing media (Lesser and Miller, 2001; Sisko et al., 2006). Quantitative measurements of growth inhibition can be achieved by measuring the optical density of liquid cultures in conventional growth assays or in 96-well liquid growth assays (Slagowski et al., 2008). Similarly, growth can be monitored using dyes that monitor cellular respiration (Sisko et al., 2006). In addition, growth on solid media can be quantified (Dudley et al., 2005).

Growth is usually measured under standard laboratory conditions. However, effector proteins targeting cellular processes that are not normally rate-limiting for growth will not be detected under these conditions. To address this, “stressors” can be introduced into the growth media at doses that do not perturb growth of wild-type yeast (Sisko et al., 2006; Slagowski et al., 2008). For example, expression of Shigella OspB only inhibits growth when caffeine is added to the media (Slagowski et al., 2008). In addition to identifying additional candidate effector proteins, conditional sensitivity to a particular stressor can provide clues as to the cellular pathway targeted by the effector protein. For example, sensitivity to high salt can be due to targeting of a variety of cellular processes including mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways, while sensitivity to nocodazole suggests a perturbation in microtubules.

There are several potential situations that might limit yeast as a model system to study specific effector proteins. For example, since the effector proteins are normally delivered as preformed toxins directly into host cells, proteins that require bacteria-specific modifications might not function in yeast. Similarly, the topology of effector proteins that are directly inserted into host cell membranes might not be maintained in yeast. To circumvent this latter issue, an option is to express soluble domains of effector proteins. This strategy proved fruitful in studying the Chlamydia trachomatis Inc proteins, a subset of Chlamydia effector proteins that are membrane associated (Sisko et al., 2006).

Significance of Growth Inhibition as a Reporter for Effector Proteins

There is growing evidence to suggest that yeast growth inhibition is a sensitive and specific reporter of effector proteins. A survey of the behavior of effector proteins and bacterial-confined proteins encoded on the Shigella virulence plasmid revealed that almost half of twenty effector proteins inhibit yeast growth when expressed from a low copy-number plasmid. A molecular mechanism was already known for seven of these proteins, five of which target conserved cellular processes. Notably, expression of only these five effectors inhibited yeast growth. Expression of the other two, which interact with proteins not found in yeast, did not affect yeast growth. Expression of only 1 of 20 bacterial-confined proteins, a bacterial toxin, severely inhibited growth. Notably, coexpression of the bacterial antitoxin suppressed yeast toxicity (Slagowski et al., 2008). Other bacterial toxin-antitoxin systems have also been observed to behave similarly in yeast (Picardeau et al., 2003; Kristoffersen et al., 2000). Presumably, these toxins target cellular processes conserved among prokaryotes and yeast.

Since some bacterial housekeeping proteins are involved in cellular processes conserved from yeast to prokaryotes, their expression also can interfere with yeast growth. For example, expression of Legionella sterol desaturase, a homolog of S. cerevisiae ERG25, an essential protein involved in ergosterol biosynthesis, presumably inhibits yeast growth by perturbing membrane synthesis (Campodonico et al., 2005). However, several high-throughput studies suggest that yeast growth inhibition due to the expression of bacterial housekeeping proteins is rare. For example, only 2 of 371 essential Pseudomonas aeruginosa proteins severely inhibit yeast growth (Arnoldo et al., 2008). Similarly, a screen that covered ~60% of the Legionella pneumophilia genome identified only six bacterial-confined proteins that inhibit yeast growth (Campodonico et al., 2005). And, lastly, expression of only 3 of ~1100 Francisella tularenesis proteins, two-thirds of the Francisella proteome, reproducibly but minimally, inhibit growth (Slagowski et al., 2008). In the case of the Pseudomonas and Legionella screens the proteins were expressed from a high copy-number plasmid while the Francisella proteins were expressed from a low copy-number plasmid. Thus, growth inhibition due to expression of bacterial-confined proteins appears to be rare, and when it does occur it appears that it is often to due to conserved targeting of cellular processes and not a nonspecific effect due to overexpression of a heterologous protein in yeast.

Subcellular Localization Patterns of Effector Proteins in Yeast Can Yield Clues to Effector Protein Function

Accumulating evidence suggests that subcellular localization patterns of effector proteins expressed de novo in yeast accurately reflect their localization when injected into host cells during the course of an infection. This includes localization to the plasma membrane, nucleus, and the actin cytoskeleton (Benabdillah et al., 2004; Lesser and Miller, 2001; Sisko et al., 2006; Skrzypek et al., 2003). This targeting presumably reflects conserved interactions with eukaryotic structures and/or proteins. However, we have observed that bacterial proteins that normally never contact host cells often localize to specific yeast cellular compartments, including the nucleus and endoplasmic reticulum, presumably due to fortuitous sequences encoded within the bacteria proteins (data not shown). Thus, localization to specific yeast subcellular compartments is not as sensitive or specific an indicator of effector proteins as growth inhibition.

The simplest way to determine the localization of an effector protein in yeast is to fuse the protein to a fluorescent tag such as GFP. Alternatively, one can conduct indirect immunofluorescence studies on fixed cells. To determine whether an effector protein localizes to specific yeast subcellular compartments, cells expressing the protein can be stained with DNA-binding dyes like DAPI (nucleus), fluorescently labeled rhodamine (actin), Mitotracker (mitochondria), or antibody markers for particular compartments. In addition, yeast reporter strains that constitutively express a series of mRFP fusion proteins that localize to specific structures are available and can be used in colocalization studies (Table 2) (Huh et al., 2003).

Table 2.

mRFP Reporter Strains for Colocalization Studies

| Strain | Localization |

| mRFP-Sac6 | actin |

| mRFP-Cop1 | early Golgi |

| mRFP-Snf7 | endosome |

| mRFP-Sec13 | ER to Golgi vesicle |

| mRFP-Anp1 | Golgi apparatus |

| mRFP-Chc1 | late Golgi/clathrin |

| mRFP-Erg6 | lipid particle |

| mRFP-Sik1 | nucleolus |

| mRFP-Nic96 | nuclear periphery |

| mRFP-Pex3 | peroxisome |

| mRFP-Spc42 | spindle pole |

Localization patterns of bacterial effector proteins in yeast can provide valuable insights regarding the molecular mechanism of the proteins. For example, when expressed in yeast, Salmonella SipA (SspA) colocalizes with the actin cytoskeleton, where it disrupts the normal yeast actin cytoskeletal polarity and prevents turnover of actin cables (Lesser and Miller, 2001). This was the first demonstration of an in vivo interaction of SipA and actin. Subsequent work in mammalian systems demonstrated that SipA bundles actin filaments by tethering actin subunits in opposing strands (Galkin et al., 2002). These activities reflect the role of SipA in promoting the formation of membrane ruffles that mediate the uptake of Salmonella into host cells.

Novel insights into pathogenesis strategies can also be gleaned from localization patterns. For example, when Sisko and colleagues screened a library of Chlamydia trachomatis ORFs fused to GFP in yeast, they observed that four putative C. trachomatis effector proteins colocalized with RFP-Erg6, a protein that localizes to yeast lipid droplets (Sisko et al., 2006). The investigators subsequently demonstrated that C. trachomatis recruits lipid droplets to the cytoplasmic surface of Chlamydia containing vacuoles and that this activity is important for the survival and replication of Chlamydia within the host cells (Kumar et al., 2006).

Expression of Effector Proteins Can Mediate Alterations in Morphology of Yeast Cytoskeleton and Organelles

The previous sections of this review describe unbiased approaches to identify and characterize effector proteins. Another approach is to screen for effector proteins that target specific eukaryotic cellular processes. For example, many pathogens manipulate the host actin cytoskeleton during the course of infection. Intracellular pathogens like Shigella and Salmonella deliver effector proteins that promote the formation of membrane ruffles that mediate their uptake into normally nonphagocytic cells (Cossart and Sansonetti, 2004; Ly and Casanova, 2007). Enteropathogenic E. coli delivers proteins into host cells that result in the formation of membrane pedestals that allow them to adhere to host cells (Hayward et al., 2006). In contrast, Yersinia species deliver effector proteins into host cells that disrupt the actin cytoskeleton and prevent their uptake by macrophages (Viboud and Bliska, 2005).

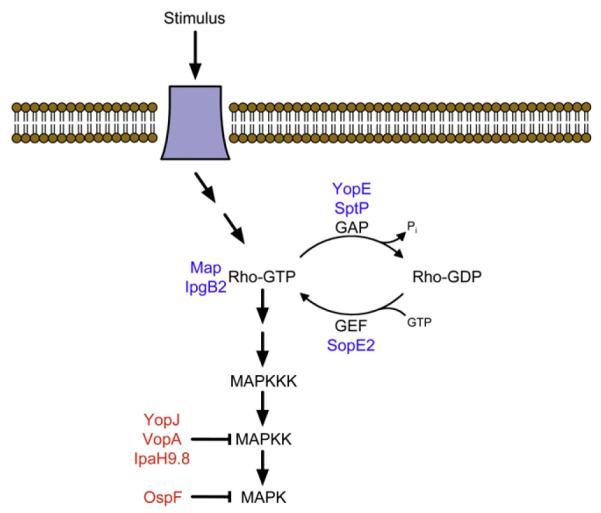

Rho GTPases are highly conserved molecular switches that regulate the dynamics of the actin cytoskeleton of both yeast and mammals (Etienne-Manneville and Hall, 2002). These proteins are activated by GEFs (GTP exchange factors) and inactivated by GAPs (GTPase-activating proteins). Effector proteins that mimic GAPs, GEFs, and activated GTPases have all been identified (Figure 1; Table 3). Although the specific responses to these proteins differ when introduced into in yeast and mammalian cells, they have been observed to exhibit analogous molecular activities when expressed in the different cell types.

Figure 1. Bacterial Effector Proteins Target Conserved Eukaryotic Signaling Pathways.

The intersection of a MAPK signaling pathway and Rho-GTPase cycling is illustrated along with the effector proteins from bacteria that target these pathways. Effector proteins with functions that mimic a mammalian protein are displayed in blue, while those that modify and deactivate mammalian proteins are displayed in red.

Table 3.

Summary of Effector Proteins that Target Rho GTPases and MAPKs

| Effector Protein | Molecular Activity (Yeast References) |

|---|---|

| Yersinia YopE | Rho GAP (Lesser and Miller, 2001; Von Pawel-Rammingen et al., 2000) |

| Shigella IpgB2 | Rho mimic (Alto et al., 2006) Salmonella SptP Rho GAP (Rodriguez-Pachon et al., 2002) |

| Salmonella SopE2 | Rho GEF (Rodriguez-Pachon et al., 2002) |

| E. coli Map | Cdc42 mimic (Alto et al., 2006) |

| Yersinia YopJ | MAPKK acetyltransferase (Yoon et al., 2003) |

| Vibrio VopA | MAPKK acetyltransferase (Trosky et al., 2007) |

| Shigella OspF | MAPK phosphothreonine lyase (Kramer et al., 2007) |

| Shigella IpaH9.8 | MAPKK (STE7) ubiquitin E3 ligase (Rohde et al., 2007) |

Expression of Yersinia YopE, a Rho GAP, inhibits the formation of actin stress fibers in mammalian cells and inhibits polarity of the yeast actin cytoskeleton (Lesser and Miller, 2001; Von Pawel-Rammingen et al., 2000). In contrast, expression of Salmonella SopE2, a Rho GEF that activates Cdc42, results in the formation of membrane ruffles in mammalian cells and causes yeast to filament, a phenotype associated with activation of the filamentous growth pathway, a MAPK pathway regulated by Cdc42 (Rodriguez-Pachon et al., 2002). Expression of E. coli Map, a functional mimic of activated Cdc42, results in the formation of filopodia in mammalian cells and results in the formation of large unbudded yeast cells with a depolarized yeast actin cytoskeleton (Rodriguez-Escudero et al., 2005). Unexpectedly, this phenotype resembles that of yeast expressing a dominant-negative, rather than a constitutively active, Cdc42 allele. One possible explanation for these results is that Map may be binding Cdc42-interacting proteins such that the endogenous yeast Cdc42 is unable to recruit proteins required to promote polarization.

Expression of E. coli EspG disrupts polarity of the yeast actin cytoskeleton (Rodriguez-Escudero et al., 2005) as well as inhibits the formation of microtubules (Hardwidge et al., 2005). Expression of both EspG and its Shigella homolog, VirA, severely inhibits yeast growth (Rodriguez-Escudero et al., 2005; Slagowski et al., 2008). In addition, both proteins bind mammalian tubulin and destabilize microtubules in in vitro assays (Hardwidge et al., 2005; Yoshida et al., 2002). Thus, effector proteins that target microtubules are also amenable to analyses in yeast.

Morphology of yeast organelles, such as the vacuole, can also provide clues to effector protein function. Sato and colleagues observed that expression of Pseudomonas aeruginosa ExoU was not only severely toxic to yeast but also resulted in a vacuole fragmentation phenotype. Based on this observation the investigators hypothesized that expression of ExoU either blocked vacuole biogenesis or disrupted vacuolar membranes. They went on to demonstrate that ExoU is a phospholipase whose activity is responsible for ExoU toxicity in both yeast and mammalian cells (Sato et al., 2003).

Yeast as a Model to Identify Proteins that Target MAPK-Signaling Cascades

MAPK-signaling cascades are ubiquitous eukaryotic cellular processes that are often targeted by effector proteins. In mammals, as in yeast, these signaling pathways regulate a variety of cellular activities. Numerous pathogens have been demonstrated to target this pathway in order to regulate the host innate immune response (Shan et al., 2007). Although the outputs of these signaling cascades differ from yeast to mammals, the signaling components of these pathways are highly conserved. These pathways are characterized by a phosphorelay of three kinases that act to transduce and amplify a variety of signals in both yeast and mammals (Figure 1). These pathways can be activated through diverse receptors and signaling molecules, including the Rho GTPases described above.

Yeast encode four well-characterized MAPK signaling pathways: the mating pathway, the filamentous growth pathway, the cell wall integrity (CWI) pathway, and the hyperosmotic growth/glycerol (HOG) pathway (Chen and Thorner, 2007). The basal activity of each of these MAPK signaling cascades is very low when yeast is grown under standard laboratory conditions. Experimental conditions exist to activate each pathway, i.e., exposure to mating factor induces the mating and filamentous growth pathways, osmotic stressors (high salt) induce the HOG pathway, and heat stress or hypo-osmotic shock induces the CWI integrity pathway. By measuring the activity of the MAPK signaling pathways in the presence and absence of the inducers, it is possible to screen for effector proteins that either activate or inhibit the pathways.

The activity of the MAPK pathways can be monitored in a variety of assays. First, transcriptional reporters for activation of all four pathways are available (Jung et al., 2002; Madhani and Fink, 1997; Tatebayashi et al., 2006; Trueheart et al., 1987). Second, mammalian phosphospecific p42/44 MAPK antibodies detect activated yeast MAPKs in the CWI, mating, and filamentous growth pathways while phospho p38 antibodies recognize the terminal MAPK in the HOG pathway. Third, one can monitor the activity of specific MAPK pathways by screening for phenotypes associated with their activation or inactivation. For example, inhibition of the mating pathway results in a complete or partial sterile phenotype, which can be detected by quantitative mating assays or by monitoring resistance to alpha factor (Hoffman et al., 2002; Sprague, 1991).

As summarized in Table 3 and outlined in Figure 1, many of the bacterial effector proteins target MAPK signaling pathways. All but one of these effector proteins exhibits the same activity in both yeast and mammalian cells. The one exception is IpaH9.8, an E3 ubiquitin ligase that targets the mating pathway MAPKK (STE7), but not its mammalian homologs, for degradation (Rohde et al., 2007). Nevertheless, the yeast studies were instrumental in determining a function for a large family of effector proteins that was previously unknown.

Analyses conducted to identify the yeast cellular target of IpaH9.8 demonstrated how the specific step in a pathway targeted by an effector protein can be identified using a variety of readily available tools (Rohde et al., 2007). Rohde and colleagues initially determined that IpaH9.8 targets the mating cascade when they observed that yeast expressing IpaH9.8 were insensitive to mating factor, a condition that normally arrests growth of haploid yeast. They next demonstrated that IpaH9.8 prevented the activation of a mating pathway transcriptional reporter when the mating pathway was activated by either mating factor or a constitutively active MAPKKK allele. In this way, they were able to determine that IpaH9.8 acts downstream of the MAPKKK. Next, using commercially available antibodies, they demonstrated that IpaH9.8-expressing yeast had greatly diminished levels of STE7 (MAPKK) but normal levels of Fus3 (MAPK). Thus, using widely available tools they were able to determine that IpaH9.8 acts at the level of the MAPKK.

The investigators did not identify the mammalian target of IpaH9.8 despite screening for alterations in the levels of at least two MAPKKs in cells infected with Shigella. Nevertheless, they were able to demonstrate that another member of this well-conserved family of effector proteins, a Salmonella homolog, does target a mammalian protein for degradation. Thus, while the studies in yeast did not clearly identify the host cell target for IpaH9.8, these studies were instrumental in determining the molecular mechanism of this family of effector proteins. Until the actual host cell target of IpaH9.8 is identified, the significance of the ubiqutination of STE7 will remain unclear as IpaH9.8 may target a mammalian protein that shares homology with STE7, including those mammalian MAPKKs not previously investigated by the investigators.

Yeast as a System to Identify Proteins that Perturb Vesicle Trafficking

Other conserved cellular pathways commonly targeted by effector proteins include those involved in vesicle trafficking. While some intracellular pathogens escape from endocytic vacuoles and survive freely in the cytoplasm, others survive within membrane-bound compartments that they modify to promote their own survival as well as to avoid fusion with lysosomes. At least two Legionella pneumophila proteins, RalF and LidA, play a role in modifying the Legionella-containing vacuole and inhibit growth when expressed in yeast (Campodonico et al., 2005; Derre and Isberg, 2005). Both of these proteins target eukaryotic proteins conserved from yeast to mammals. Expression of LidA interferes with the processing of carboxypeptidase Y (CPY), a protein that is modified as it is processed from the ER to the Golgi to the vacuole. Thus, LidA likely inhibits yeast growth by interfering with vesicular trafficking (Derre and Isberg, 2005).

An elegant yeast screen previously used to identify yeast strains impaired in the transport of proteins to the vacuole was adapted to screen for Legionella pneumophila effector proteins that specifically target this trafficking pathway. As described above, CPY is a vacuolar protein that is normally transported from the ER-Golgi vacuole. The fusion of the terminal 50 amino acids of CPY to invertase (Inv), a protein that breaks down sucrose, is sufficient to target Inv to the yeast vacuole, where it is degraded. However, when the vacuole transport pathway is disrupted, the fusion protein is missorted to yeast cell surface, where it is secreted. The secreted invertase is functional, and its activity can be detected in a simple overlay assay. A genomic library of L. pneumophila chromosomal DNA fragments under the control of the constitutive yeast ADH1 promotor was introduced into the CPY-Inv reporter strain and screened for those proteins that perturb vesicle trafficking. Three previously unknown Legionella effector proteins were subsequently identified (Shohdy et al., 2005). LidA and RalF were not detected in this screen, presumably due to their toxicity to yeast. This screen should be applicable to screening ORFs from a variety of bacterial pathogens.

Yeast Functional Genomic Screens Provide Unique Insights into the Host Cell Processes Targeted by Effector Proteins

The previous sections of this review all describe relatively straightforward strategies for identifying the cellular targets in yeast of the effector proteins. Since these targets are often conserved, studies in yeast can provide valuable insights regarding the roles of these proteins in pathogenesis. Functional genomics provides a powerful alternative approach. Given its relatively small genome, genetic tractability and well-developed functional genomic tools, S. cerevisiae is an ideal model organism for multidisciplinary systems-biology studies. Since over 75% of the yeast genome is functionally annotated, systematic identification of genes or proteins that modulate a phenotype can identify pathways and processes involved in that phenotype, which, in turn, can provide insights into the phenotype’s etiology.

Yeast functional genomic screens have recently been used to characterize the functions of two Shigella effector proteins, IpgB2 and OspF. In both cases, the effector protein under the control of the inducible GAL1/10 promotor was introduced into the complete set of ~4800 yeast haploid deletion strains, each deleted for a nonessential annotated yeast ORF. The two studies demonstrate different approaches that can be undertaken to identify host cell processes targeted by effector proteins. For IpgB2, Alto and colleagues screened for and identified three deletion strains that suppress the lethal yeast phenotype associated with expression of this protein (Alto et al., 2006). In the case of OspF, Kramer and colleagues systematically screened for and identified 78 yeast deletion strains hypersensitive to expression of OspF (Kramer et al., 2007). While the suppressor screens specifically identified deletion strains that counteracted the effects of expression of IpgB2, the hypersensitivity screens identified deletion strains that exacerbated the OspF growth phenotype.

Remarkably, both functional genomic screens suggested that IpgB2 and OspF were targeting the yeast cell wall integrity pathway, a highly conserved MAPK signaling pathway. IpgB2 toxicity was alleviated when proteins essential for the integrity of this signal pathway were deleted. In contrast, many of the deletion strains hypersensitive to expression of OspF were observed to be involved in processes that required the presence of an intact cell wall. In parallel with the genome-wide phenotypic screens, both laboratories used microarray technology to identify genome-wide alterations in the expression of yeast mRNAs due to expression of the effector proteins. In both cases, expression patterns of genes normally regulated by the CWI pathway were disrupted. In the case of IpgB2 the pathway was constitutively activated, while in the case of OspF the pathway was repressed. These functional genomic studies, in part, resulted in the classification of IpgB2 as a founding member of a new family of effector proteins that mimic activated Rho GTPases and OspF as a member of a newly established class of MAPK phosphatases, phosphothreonine lyases.

Although both the screens described above were conducted with the yeast deletion strain collection, similar approaches can be undertaken by systematically examining the effects of expressing effector proteins in one of the available collections of yeast strains that conditionally overexpress each of the annotated yeast ORFs (Gelperin et al., 2005; Sopko et al., 2006).

Suppression of Yeast Growth Inhibition Provides a Novel Assay for Detection of Small Molecule Inhibitors

As described earlier, expression of effector proteins can result in severe yeast growth inhibition. If these effector proteins play a major role in virulence, then one can potentially identify new antivirulence molecules by screening for compounds that inhibit the effector protein activity. This strategy was recently undertaken to screen a library of 56,000 small molecules for those that inhibit yeast growth inhibition due to expression of Pseudomonas aeruginosa ExoS (Arnoldo et al., 2008). Six compounds were identified, one of which, exosin, also protects mammalian cells from the toxic effects of ExoS, an effector protein that exhibits both RhoGAP and ADP-ribosyltransferase activity (ADPRT). Interestingly, exosin specifically targets the ExoS ADPRT activity, which appears to be sufficient to both suppress ExoS yeast toxicity as well as to prevent the induction of apoptosis of host cells due to infection of P. aeruginosa. One could also use this approach to screen for compounds that inhibit the activity of essential bacterial proteins whose expression severely inhibits yeast growth.

There are several advantages of conducting screens for small molecule inhibitors in yeast. First, since the screens are conducted outside of the context of an infection, they are conducted under Biosafety Level 1 conditions. Second, since small molecules are being screened for alleviation of growth inhibition and the readout is restoration of growth, toxic compounds that target conserved eukaryotic cellular pathways will likely be screened out. Lastly, since compounds that restore yeast growth are presumably able to penetrate both the yeast cell wall and plasma membrane, small molecule screens conducted in yeast should enrich for compounds that can be taken up by mammalian cells. Of note, yeast strains that no longer express proteins involved in mediating pleiotrophic drug resistance (Pdr1, Pdr3, and Snq2) as well as proteins involved in synthesis of the plasma membrane (Erg6) can be used to potentially increase the intracellular concentrations of the small molecules being screened.

Conclusions

This review describes many approaches using S. cerevisiae that numerous laboratories studying plant and human pathogens are undertaking to both identify and characterize bacterial proteins involved in virulence. Notably, even though this relatively simple eukaryote does not encode an immune system, effector proteins involved in modulating the host immune response like Yersinia YopJ and Shigella OspF are amenable to analyses in yeast because they target highly conserved MAPK signaling pathways. The yeast system should prove fruitful in identifying effector proteins that play roles in modulating other processes unique to multicellular organisms that are also regulated by conserved signaling pathways.

The verdict is still out on the general utility of the yeast system for studying bacterial effector proteins. It has been clearly demonstrated that a variety of effector proteins target GTPases and MAPK signaling cascades in both yeast and mammals, and, as reviewed above, targeted assays can now be used to screen for such proteins. Although this review focused on common functional themes shared among virulence factors, effector proteins have been observed to target a variety of cellular processes conserved from yeast to mammals (for review, see Valdivia, 2004). For example, P. aeruginosa ExoS is an ADPRT that targets members of Ras family in both yeast and mammalian cells, Salmonella SipA (SspA) colocalizes and decreases the turnover of actin filaments in both yeast and mammalian cells, and numerous plant effector proteins inhibit programmed cell death of both yeast and plant cells (Abramovitch et al., 2006; Jamir et al., 2004). Thus, it seems likely that the yeast model system will prove useful in identifying additional functions for a variety of effector proteins, especially when unbiased genetic approaches are undertaken.

The main advantage of studying bacterial pathogens in yeast as opposed to other model systems like Caenorhabditis elegans or Drosophila melanogaster is the relative simplicity of this system. The simplicity may also be an Achilles heel, though, as some effector proteins undoubtedly target host proteins unique to mammals. Indeed, some effector proteins known to target nonconserved eukaryotic proteins do not visibly affect growth when expressed in yeast. Furthermore, although bacterial effector proteins are known to work in concert, all studies so far have focused on individual effector proteins outside of the context of an infection. Yet, coexpression of multiple effector proteins in yeast is quite feasible and should be a fruitful undertaking in the future. The relative ease of working with S. cerevisiae and the wealth of available experimental tools coupled with the high conservation of many eukaryotic cellular processes make this system a very powerful one in which to study mechanisms of bacterial pathogenesis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Roie Levy, Alexa Schmitz, and Sarah Paglioni Fankhauser for helpful discussions. We also thank Bindu Sukumaran, Seth Maleri, Roger Kramer, Jason Heindl, Manish Sagar, and an anonymous reviewer for critically reading the manuscript. The NIH (AI068924) funds our work, and C.F.L. is a Charles E. Culpeper Medical Scholar of Goldman Philanthropic Partnerships, supported by the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, and Goldman Philanthropic Partnerships.

REFERENCES

- Abramovitch RB, Janjusevic R, Stebbins CE, Martin GB. Type III effector AvrPtoB requires intrinsic E3 ubiquitin ligase activity to suppress plant cell death and immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:2851–2856. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507892103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aleman A, Rodriguez-Escudero I, Mallo GV, Cid VJ, Molina M, Rotger R. The amino-terminal non-catalytic region of Salmonella typhimurium SigD affects actin organization in yeast and mammalian cells. Cell. Microbiol. 2005;7:1432–1446. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alto NM, Shao F, Lazar CS, Brost RL, Chua G, Mattoo S, McMahon SA, Ghosh P, Hughes TR, Boone C, et al. Identification of a bacterial type III effector family with G protein mimicry functions. Cell. 2006;124:133–145. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnoldo A, Curak J, Kittanakom S, Chevelev I, Lee VT, Sahebol-Amri M, Koscik B, Ljuma L, Roy PJ, Bedalov A, et al. Identification of small molecule inhibitors of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Exoenzyme S using a yeast phenotypic screen. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000005. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belli G, Gari E, Piedrafita L, Aldea M, Herrero E. An activator/ repressor dual system allows tight tetracycline-regulated gene expression in budding yeast. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:942–947. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.4.942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benabdillah R, Mota LJ, Lutzelschwab S, Demoinet E, Cornelis GR. Identification of a nuclear targeting signal in YopM from Yersinia spp. Microb. Pathog. 2004;36:247–261. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2003.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campodonico EM, Chesnel L, Roy CR. A yeast genetic system for the identification and characterization of substrate proteins transferred into host cells by the Legionella pneumophila Dot/Icm system. Mol. Microbiol. 2005;56:918–933. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen RE, Thorner J. Function and regulation in MAPK signaling pathways: lessons learned from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2007;1773:1311–1340. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cossart P, Sansonetti PJ. Bacterial invasion: the paradigms of enteroinvasive pathogens. Science. 2004;304:242–248. doi: 10.1126/science.1090124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeRisi JL, Iyer VR, Brown PO. Exploring the metabolic and genetic control of gene expression on a genomic scale. Science. 1997;278:680–686. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5338.680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derre I, Isberg RR. LidA, a translocated substrate of the Legionella pneumophila type IV secretion system, interferes with the early secretory pathway. Infect. Immun. 2005;73:4370–4380. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.7.4370-4380.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudley AM, Janse DM, Tanay A, Shamir R, Church GM. A global view of pleiotropy and phenotypically derived gene function in yeast. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2005;1:2005–0001. doi: 10.1038/msb4100004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etienne-Manneville S, Hall A. Rho GTPases in cell biology. Nature. 2002;420:629–635. doi: 10.1038/nature01148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galkin VE, Orlova A, VanLoock MS, Zhou D, Galan JE, Egelman EH. The bacterial protein SipA polymerizes G-actin and mimics muscle nebulin. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2002;9:518–521. doi: 10.1038/nsb811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelperin DM, White MA, Wilkinson ML, Kon Y, Kung LA, Wise KJ, Lopez-Hoyo N, Jiang L, Piccirillo S, Yu H, et al. Biochemical and genetic analysis of the yeast proteome with a movable ORF collection. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2816–2826. doi: 10.1101/gad.1362105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaemmaghami S, Huh WK, Bower K, Howson RW, Belle A, Dephoure N, O’Shea EK, Weissman JS. Global analysis of protein expression in yeast. Nature. 2003;425:737–741. doi: 10.1038/nature02046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giaever G, Chu AM, Ni L, Connelly C, Riles L, Veronneau S, Dow S, Lucau-Danila A, Anderson K, Andre B, et al. Functional profiling of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome. Nature. 2002;418:387–391. doi: 10.1038/nature00935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardwidge PR, Deng W, Vallance BA, Rodriguez-Escudero I, Cid VJ, Molina M, Finlay BB. Modulation of host cytoskeleton function by the enteropathogenic Escherichia coli and Citrobacter rodentium effector protein EspG. Infect. Immun. 2005;73:2586–2594. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.5.2586-2594.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward RD, Leong JM, Koronakis V, Campellone KG. Exploiting pathogenic Escherichia coli to model transmembrane receptor signalling. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2006;4:358–370. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman GA, Garrison TR, Dohlman HG. Analysis of RGS proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Methods Enzymol. 2002;344:617–631. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)44744-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh WK, Falvo JV, Gerke LC, Carroll AS, Howson RW, Weissman JS, O’Shea EK. Global analysis of protein localization in budding yeast. Nature. 2003;425:686–691. doi: 10.1038/nature02026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamir Y, Guo M, Oh HS, Petnicki-Ocwieja T, Chen S, Tang X, Dickman MB, Collmer A, Alfano JR. Identification of Pseudomonas syringae type III effectors that can suppress programmed cell death in plants andyeast. Plant J. 2004;37:554–565. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung US, Sobering AK, Romeo MJ, Levin DE. Regulation of the yeast Rlm1 transcription factor by the Mpk1 cell wall integrity MAP kinase. Mol. Microbiol. 2002;46:781–789. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer RW, Slagowski NL, Eze NA, Giddings KS, Morrison MF, Siggers KA, Starnbach MN, Lesser CF. Yeast functional genomic screens lead to identification of a role for a bacterial effector in innate immunity regulation. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e21. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristoffersen P, Jensen GB, Gerdes K, Piskur J. Bacterial toxin-antitoxin gene system as containment control in yeast cells. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000;66:5524–5526. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.12.5524-5526.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar Y, Cocchiaro J, Valdivia RH. The obligate intracellular pathogen Chlamydia trachomatis targets host lipid droplets. Curr. Biol. 2006;16:1646–1651. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.06.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesser CF, Miller SI. Expression of microbial virulence proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae models mammalian infection. EMBO J. 2001;20:1840–1849. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.8.1840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ly KT, Casanova JE. Mechanisms of Salmonella entry into host cells. Cell. Microbiol. 2007;9:2103–2111. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.00992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madhani HD, Fink GR. Combinatorial control required for the specificity of yeast MAPK signaling. Science. 1997;275:1314–1317. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5304.1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- March JC, Rao G, Bentley WE. Biotechnological applications of green fluorescent protein. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2003;62:303–315. doi: 10.1007/s00253-003-1339-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munkvold KR, Martin ME, Bronstein PA, Collmer A. A survey of the Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 type III secretion system effector repertoire reveals several effectors that are deleterious when expressed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2008;21:490–502. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-21-4-0490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nejedlik L, Pierfelice T, Geiser JR. Actin distribution is disrupted upon expression of Yersinia YopO/YpkA in yeast. Yeast. 2004;21:759–768. doi: 10.1002/yea.1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picardeau M, Le Dantec C, Richard GF, Saint Girons I. The spirochetal chpK-chromosomal toxin-antitoxin locus induces growth inhibition of yeast and mycobacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2003;229:277–281. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00848-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piers KL, Heath JD, Liang X, Stephens KM, Nester EW. Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation of yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:1613–1618. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.4.1613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabin SD, Hauser AR. Pseudomonas aeruginosa ExoU, a toxin transported by the type III secretion system, kills Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Infect. Immun. 2003;71:4144–4150. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.7.4144-4150.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Escudero I, Hardwidge PR, Nombela C, Cid VJ, Finlay BB, Molina M. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli type III effectors alter cytoskeletal function and signalling in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiology. 2005;151:2933–2945. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28072-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Pachon JM, Martin H, North G, Rotger R, Nombela C, Molina M. A novel connection between the yeast Cdc42 GTPase and the Slt2-mediated cell integrity pathway identified through the effect of secreted Salmonella GTPase modulators. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:27094–27102. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201527200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohde JR, Breitkreutz A, Chenal A, Sansonetti PJ, Parsot C. Type III secretion effectors of the IpaH family are E3 ubiquitin ligases. Cell Host Microbe. 2007;1:77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato H, Frank DW, Hillard CJ, Feix JB, Pankhaniya RR, Moriyama K, Finck-Barbancon V, Buchaklian A, Lei M, Long RM, et al. The mechanism of action of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa-encoded type III cytotoxin, ExoU. EMBO J. 2003;22:2959–2969. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan L, He P, Sheen J. Intercepting host MAPK signaling cascades by bacterial type III effectors. Cell Host Microbe. 2007;1:167–174. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shohdy N, Efe JA, Emr SD, Shuman HA. Pathogen effector protein screening in yeast identifies Legionella factors that interfere with membrane trafficking. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:4866–4871. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501315102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisko JL, Spaeth K, Kumar Y, Valdivia RH. Multifunctional analysis of Chlamydia-specific genes in a yeast expression system. Mol. Microbiol. 2006;60:51–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skrzypek E, Myers-Morales T, Whiteheart SW, Straley SC. Application of a Saccharomyces cerevisiae model to study requirements for trafficking of Yersinia pestis YopM in eucaryotic cells. Infect. Immun. 2003;71:937–947. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.2.937-947.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slagowski NL, Kramer RW, Morrison MF, LaBaer J, Lesser CF. A functional genomic yeast screen to identify pathogenic bacterial proteins. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e9. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0040009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sopko R, Huang D, Preston N, Chua G, Papp B, Kafadar K, Snyder M, Oliver SG, Cyert M, Hughes TR, et al. Mapping pathways and phenotypes by systematic gene overexpression. Mol. Cell. 2006;21:319–330. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprague GF., Jr. Assay of yeast mating reaction. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:77–93. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94008-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stirling FR, Evans TJ. Effects of the type III secreted pseudomonal toxin ExoS in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiology. 2006;152:2273–2285. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28831-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatebayashi K, Yamamoto K, Tanaka K, Tomida T, Maruoka T, Kasukawa E, Saito H. Adaptor functions of Cdc42, Ste50, and Sho1 in the yeast osmoregulatory HOG MAPK pathway. EMBO J. 2006;25:3033–3044. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trosky JE, Li Y, Mukherjee S, Keitany G, Ball H, Orth K. VopA inhibits ATP binding by acetylating the catalytic loop of MAPK kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:34299–34305. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706970200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trueheart J, Boeke JD, Fink GR. Two genes required for cell fusion during yeast conjugation: evidence for a pheromone-induced surface protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1987;7:2316–2328. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.7.2316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uetz P, Giot L, Cagney G, Mansfield TA, Judson RS, Knight JR, Lockshon D, Narayan V, Srinivasan M, Pochart P, et al. A comprehensive analysis of protein-protein interactions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature. 2000;403:623–627. doi: 10.1038/35001009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdivia RH. Modeling the function of bacterial virulence factors in Saccharmoyces cerevisiae. Eukaryot. Cell. 2004;3:827–834. doi: 10.1128/EC.3.4.827-834.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viboud GI, Bliska JB. Yersinia outer proteins: role in modulation of host cell signaling responses and pathogenesis. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2005;59:69–89. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.59.030804.121320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Pawel-Rammingen U, Telepnev MV, Schmidt G, Aktories K, WolfWatz H, Rosqvist R. GAP activity of the Yersinia YopE cytotoxin specifically targets the Rho pathway: a mechanism for disruption of actin microfilament structure. Mol. Microbiol. 2000;36:737–748. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon S, Liu Z, Eyobo Y, Orth K. Yersinia effector YopJ inhibits yeast MAPK signaling pathways by an evolutionarily conserved mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:2131–2135. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209905200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida S, Katayama E, Kuwae A, Mimuro H, Suzuki T, Sasakawa C. Shigella deliver an effector protein to trigger host microtubule desta-bilization, which promotes Rac1 activity and efficient bacterial internalization. EMBO J. 2002;21:2923–2935. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H, Klemic JF, Chang S, Bertone P, Casamayor A, Klemic KG, Smith D, Gerstein M, Reed MA, Snyder M. Analysis of yeast protein kinases using protein chips. Nat. Genet. 2000;26:283–289. doi: 10.1038/81576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]