Abstract

Proteases play prominent roles in many physiological processes and the pathogenesis of various diseases, which makes them interesting drug targets. To fully understand the functional role of proteases in these processes, it is necessary to characterize the target specificity of the enzymes, identify endogenous substrates and cleavage products as well as protease activators and inhibitors. The complexity of these proteolytic networks presents a considerable analytic challenge. To comprehensively characterize these systems, quantitative methods that capture the spatial and temporal distributions of the network members are needed. Recently, activity-based workflows have come to the forefront to tackle the dynamic aspects of proteolytic processing networks in vitro, ex vivo and in vivo. In this review, we will discuss how mass spectrometry-based approaches can be used to gain new insights into protease biology by determining substrate specificities, profiling the activity-states of proteases, monitoring proteolysis in vivo, measuring reaction kinetics and defining in vitro and in vivo proteolytic events. In addition, examples of future aspects of protease research that go beyond mass spectrometry-based applications are given.

Keywords: Dynamic proteomics, mass spectrometry, proteases, proteolytic networks, stable isotope labeling

INTRODUCTION

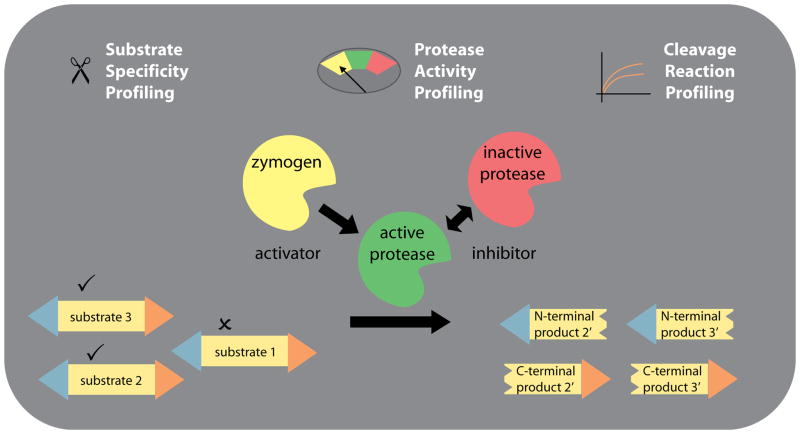

In the emerging post-reductionist era of biochemistry, proteins are considered members of complex dynamic networks [1]. Proteolytic enzymes that process and degrade proteins are mediators of protein dynamics and are themselves organized in networks. Genomic studies have identified more than 550 human proteases and their role has been described in diverse physiological processes including apoptosis, blood clotting and hormone signaling [2]. Despite the biological importance of proteases, the systems biology of proteolytic networks is still under-characterized. Proteolytic networks are minimalistically comprised of proteases, substrates, cleavage products and modulators of protease activities such as activators and inhibitors (Figure 1). Their interplay is dynamic, both spatially and temporally, and protease function is influenced by environmental factors (e.g., local changes of pH, influx of calcium ions). Ultimately, the goal of post-reductionist protein science is to study proteins in situ and gain insights into the influence of the cellular context. Classical proteomics experiments often yield long, indiscriminate lists of identified molecules. Activity-based proteomics experiments that focus on the analysis of protein dynamics approximate in vivo conditions and can thereby help to prioritize results based on their physiological relevance. The concept of protein dynamics – the spatiotemporal distribution and interplay of network members in the context of a cell - can be considered a subcategory of systems biology. Studying protein dynamics gives a holistic view of biological processes, helps establishing functional relationships between proteolytic network components and increases our understanding of their physiological and pathological roles.

Figure 1. Profiling proteolytic networks.

Most proteolytic enzymes are expressed as inactive zymogens and need to be activated before they can cleave substrates. Protease inhibitors further regulate the activities of proteases. Protease activity profiling methods determine the net activity of proteases. Substrate specificity profiling methods determine which substrates are recognized by proteases. Cleavage reaction profiling methods analyze the temporal aspects of substrate-to-product conversions.

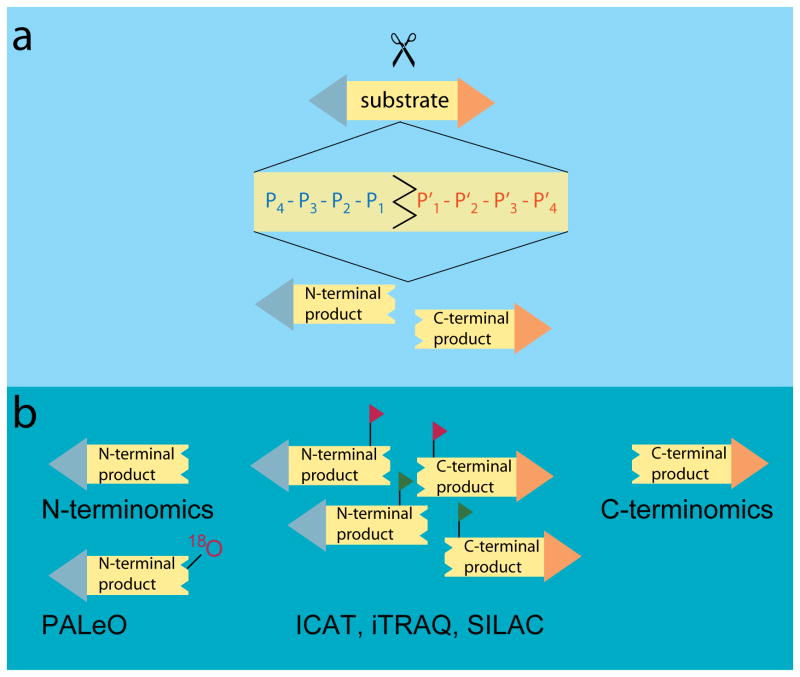

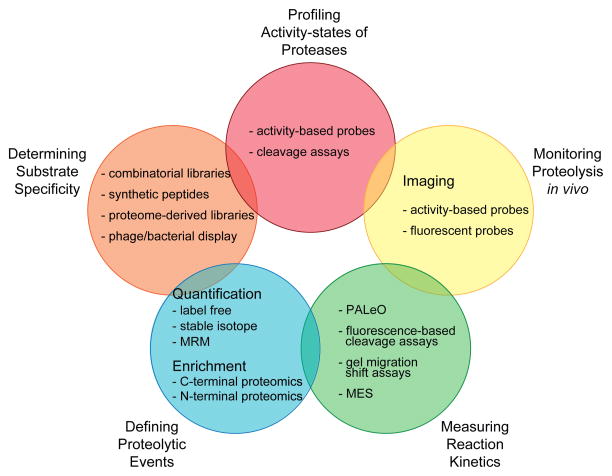

Interactions between proteases and their substrates are central to our understanding of proteolysis. Determining the cleavage preference of a protease is the logical first step to define the functional relationships between members of a proteolytic network. The architecture of the active site is the primary determinant of protease specificity due to its ability to recognize amino acid sequences flanking the scissile peptide bond on the substrate molecule. The amino acid residues surrounding the cleavage site are denoted P4-P3-P2-P1-↓-P1′-P2′-P3′-P4′ based on the nomenclature introduced by Schechter and Berger [3] with cleavage occurring at the peptide bond between residues P1 and P1′ (Figure 2a). The contribution to selectivity by individual residues within the recognition site can vary. Other factors that also influence protease-substrate interactions are exosites located outside of the active sites, overall protein structure and the local structural presentation of the cleavage site. Accordingly, a wide range of specificity levels has been observed for proteases, ranging from the promiscuous cutting preference of digestive proteases to the narrow and finely tuned specificities of signaling peptidases. From an analytical standpoint, it would be ideal to simultaneously take all contributing factors that regulate protease specificity into consideration, however this still constitutes an insurmountable technical challenge. Recent MS-technology developments, however, indicate that the transition from reductionist to more holistic, systems-biology oriented studies is well under way (Figure 3). In this review, we highlight how these methods explore the contextual influence on protease-substrate interactions.

Figure 2. (a) Schematic representation of a proteolytic cleavage site and (b) MS-based strategies for identifying N- and C-terminal cleavage products.

(a) Substrate cleavage occurs at the scissile bond between residues P1 - P1′ in the Schechter and Berger representation of the protease recognition site. (b) Reaction products can be identified using N- and C-terminomics approaches that enrich terminal cleavage products; isotopic labeling methods (ICAT, iTRAQ, SILAC) allow for the quantification of peptide products; PALeO labels newly formed N-terminal cleavage products with 18O-atoms during proteolysis.

Figure 3. Overview of MS-based technologies utilized in protease research.

The complex and dynamic nature of proteolytic networks requires the application of multiple analytic strategies. MS-based methods are being used to determine substrate specificities, profile the activity-states of proteases, monitor proteolysis in vivo, measure the kinetics of proteolytic cleavage reactions and define in vitro and in vivo proteolytic events.

In vitro protease specificity profiling with substrate libraries

The overall substrate preferences of proteases are typically established by true reductionist approaches, in which purified proteases are exposed to libraries of peptide/protein substrates. Several substrate library formats have been developed. Combinatorial chemistry has been used to generate diverse peptide repertoires, in which fluorescent-based moieties report on cleavages [4, 5]. Positional scanning libraries have been developed to fine probe the subsite preference of proteases by altering one residue at a time [6, 7]. Fluorogenic peptides have been presented in microarrays to enable the direct assessment of individual peptide sequences by measuring fluorescent spot intensities [8]. An iterative approach that establishes protease specificity using peptide libraries with increasingly constrained amino acid sequences has also been designed [9]. Since the overall protein structure influences protease-substrate interactions as well, phage [10] and bacterial display [11] technologies have been developed to present substrates in the context of entire proteins. While most of these library approaches are scalable, they are incapable of presenting the entire combinatorial space encoded by amino acids. Therefore, libraries that focus on a biologically relevant sequence space are interesting alternatives. MS-based screening of proteome-derived peptide libraries (e.g., generated by digestion of cell lysates) can increase the proportion of physiological substrates by harnessing the natural peptide sequence diversity [12].

Taken together, the library approaches summarized here yield a comprehensive, in vitro catalogue of protease substrates. Bioinformatical tools such as WebLogo [13] and iceLogo [14] help identifying amino acid sequence conservations at positions flanking the cleavage site. The probability calculation by iceLogo takes into account small experimental sample sets and further improves the visualization of consensus sequences by allowing for custom reference sets.

However, these consensus recognition sequences are abstract depictions of amino acid preferences and may not properly represent the preference of proteases under physiological conditions. Without taking the biochemical context into consideration, few insights into environmental influences on protease specificity and the underlying biology are gained. Nonetheless, in vitro protease specificity profiles can increase the confidence in candidate substrates identified in corroborating cell-contextual cleavage experiments.

Approximating in vivo cleavage sites with terminal proteomics

To overcome the shortcomings of in vitro substrate library approaches, terminal proteomics techniques have been developed that focus on the elucidation of proteolytic cleavage sites in complex biological backgrounds, thereby approximating the in vivo state. Terminal proteomics, also known as terminomics and positional proteomics, reveals proteolytic processing sites by mapping the flanking N- or C-terminal peptides produced as the result of proteolytic cleavage [15–19]. These emergent neo-termini contain the prime and non-prime sites of the protease recognition sequence (Figure 2). Since protein substrates are presented in their natural structural conformation, terminal proteomics studies assemble catalogues of biologically relevant protease substrate inventories. To define protease cleavage specificity, the amino acid sequences surrounding the scissile peptide bond are determined directly from the MS-data or are derived by bioinformatics. Typically, the proteolytic enzymes of interest will process only a small portion of proteins in complex biological matrices. Therefore, enrichment schemes that focus the analysis on cleavage products are useful approaches to increase sensitivity and selectivity. Enrichment strategies can generally be categorized into positive and negative selection schemes for N- and C-terminal cleavage products. In N-terminal positive selection workflows, lysine side chains are blocked (e.g., by guanidination) and free α-amines generated during proteolysis are specifically labeled with affinity reagents using either chemical [20, 21] or enzymatic [22] reactions. After digestion (typically with trypsin), labeled peptides are affinity-purified and their sequences determined by LC-MS/MS. In N-terminal negative selection workflows, less informative, internal peptides that were generated during the tryptic protein digestion step are captured using chemical means [16, 23, 24] or are sorted out by combined fractional diagonal chromatography (COFRADIC) [25]. C-terminal proteomics is more challenging due to the lower chemical reactivity of the α-carboxyl group. The recent introduction of a negative enrichment strategy for C-terminal peptides by Schilling et al. may open new possibilities [26].

Negative enrichment schemes have a strategic advantage over positive enrichment methods, since they do not rely as heavily on the efficiency of the chemical derivatization step, as only a relative enrichment and reduction of sample complexity are sought. Nevertheless, a general shortcoming of terminal enrichment methods is the necessity for multiple sample processing steps prior to MS analysis that could introduce bias. For example, it has been reported that positive-selection techniques have a bias regarding the amino acid composition of the P1′ site [17]. To date, no bias for particular terminal amino acid residues has been reported in the literature for negative-selection techniques.

From a bioinformatic standpoint, target identifications frequently rely on single peptide matches, which render terminal proteome experiments by definition prone to low identification rates. Since the peptides that are formed in these experiments are not exclusively of tryptic origin, additional cleavage specificities have to be added to MS-database search parameters, which effectively increases the sequence search space and raises significance thresholds. False-discovery rates can be estimated on the global level [27] or for individual peptide identifications using the PeptideProphet tool [28]. Post processing tools such as Peptizer can be used to actively constraint acceptable results based on user-configured parameters (peptide sequence length, fragment ion coverage, etc.) [29]. The number of correctly identified peptides can also be increased by iProphet [30], a recent addition to the Trans-Proteomics Pipeline data analysis suite [31], which allows combining peptide identification evidence across different spectra, experiments, precursor ion charge states and peptide modification states, as well as integrating results from multiple search engines [32].

Terminal proteomics studies can only approximate in vivo proteolysis. By focusing on the amino acid regions directly flanking the cleavage site, the perspective on the fate of the entire protein substrate is often lost. On their own, terminal approaches provide little information on the spatiotemporal distributions of protease substrates. Normal protein maturation processes (e.g., N-terminal methionine excision, leader peptide removal) are proteolytic in nature and contribute to the diversity of terminal protein sequences. The presence of additional, endogenous proteases can also lead to considerable unspecific background signals that need to be accounted for. Knowledge of the in vitro specificity of a protease under investigation can help differentiating the origin of cleavage products. A further increase in the specificity of terminal proteomics experiments and improvement of the identification of biologically relevant substrates can be achieved by the application of differential and quantitative labeling techniques, as described in the following section.

Adding quantitative MS-measurements to reveal proteolytic events

While MS-based terminomics experiments yield the identities of members of proteolytic networks, they provide on their own little information about the kinetics of cleavage reactions and factors such as protein structure that influence the interplay of proteases and substrates. Furthermore, one of the challenges that emerges from terminomics studies is how to prioritize the ever-increasing number of network components. Differentiating cleavage products based on their physiological relevance will help define key targets in proteolytic pathways. Up-and-coming MS-based quantitation strategies based on isotope dilution and label-free technologies enable comparative analyses [33]. Isotope labels can be introduced by chemical derivatization, metabolic incorporation or during the digestion step by exogenous proteases. All major labeling approaches have now been employed in protease research. In the simplest scenario, these workflows can be used to identify potential substrates as those having altered protein expression levels in response to protease transfection. Isotope-coded affinity tag (ICAT) labeling, which is based on a cysteine-specific binary labeling strategy, has been used to identify targets of the human membrane type 1-MMP [34] and MMP-2 [35]. Kleifeld et al. determined the MMP-2 substrate repertoire by isotopically encoding formaldehyde to differentially label amino groups prior to negative enrichment [32]. Van Damme et al. used 16O/18O-based differential labeling and COFRADIC-based N-terminal peptide enrichment to differentiate proteolytic cleavage products from apoptotic and living cells [36]. These initial quantitative approaches typically used binary comparison strategies (absence/presence of catalytically active protease) to define protease substrate repertoires, but often failed to pinpoint the precise sites of cleavages. The next generation of approaches addressed this shortcoming by combining isotope-labeling techniques with terminal proteomics strategies. For example, Enoksson et al. used isobaric tag for relative and absolute quantitation (iTRAQ) reagents to label the N-termini emerging from cleavage reactions to define the substrate repertoire of caspase-3 [37]. The recently extended iTRAQ-labeling chemistry now enables multiplexed quantification of up to eight samples. Since iTRAQ-based quantitation occurs in MS/MS mode, an increase in spectral complexity is avoided, which makes this approach attractive for the analysis of complex biological samples. Prudova et al. used an iTRAQ-based four-plex approach to compare the substrate repertoire of MMP-2 and -9 [38]. The multiplexing capability of iTRAQ was also used in a study by Dean et al. that monitored the flux of cleavage products by determining the relative expression levels of protease targets across multiple time points [39].

Stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture (SILAC) is a promising, metabolic labeling technique that circumvents the need for chemical derivatization [40]. Therefore, SILAC is less subject to technical variation caused by sample processing. Gioia et al. used SILAC and N-terminal negative enrichment to reveal the substrate repertoire of MMP-2 in human breast cancer cells [41]. Van Damme et al. used SILAC in conjunction with the COFRADIC N-terminal enrichment strategy to compare human and murine substrates of Granzyme B [42]. Plasman et al. encoded three incubation periods of a proteolytic reaction with SILAC and used the N-terminal COFRADIC enrichment procedure to monitor the flux of cleavage products and determine sites efficiently cleaved by human Granzyme B [43].

While stable isotope-based labeling approaches offer higher accuracy, label-free approaches are becoming increasingly popular alternative methods to estimate protein abundances. Gupta et al. used label-free MS in conjunction with the MS-Proteolysis tool to retrospectively map endogenous proteolytic cleavages that are distinct from cuts induced by tryptic digestion [44]. In vivo cleavage site positions were confirmed by comparing the results obtained from digests using additional exogenous proteases (e.g., Glu-C, chymotrypsin). This approach has been used to detect proteolytic events that are related to protein maturation, such as the excision of N-terminal methionines by methionine aminopeptidases and the removal of signal peptides by signal peptidases. Xu et al. also used a label-free quantitative shotgun proteomics approach to identify novel MMP-9 cleavage targets in cancer cell lines [45]. While label-free and SILAC methodologies side-step some of the sample processing steps necessary in other quantitation workflows, few of the published studies have been able to analyze sufficient time points to capture the dynamics of proteolytic processing. Adding temporal aspects to these quantitation techniques will ultimately enhance comparative studies that, for example, investigate the effect of perturbations on proteolytic networks.

Analyzing dynamics of proteolysis by measuring gel migration shifts

Gel-based approaches that monitor the shifts of protein migration in response to protease exposure are a technically accessible way for identifying proteolytic cleavages on the intact protein level. This approach has been used in 1-D- and 2-D-formats using colloidal Coomassie [46], ruthenium [47] or silver staining [48]. DIGE-fluorophore labeling allows for the identification of protease substrates in the same gel [49]. Quantitation is provided by densitometry, protein identities are determined by MS and cleavage kinetics are analyzed by sampling different time points in 1-D gels. The ease and flexibility makes gel-based approaches a common validation tool for proteomics-based studies [50], however by themselves these techniques suffer from limited resolution and sensitivity. The hyphenation of gel-based approaches with Edman sequencing or MS-based workflows enables a more detailed determination of cleavage sites. For example, the PROTOMAP-approach is a 1-D gel-LC-MS/MS hybrid approach that uses MS-based protein sequence coverage data to ballpark cleavage site locations and label-free MS spectral counts to estimate protein expression levels. PROTOMAP has been used to determine proteolytic events that occur during apoptosis [51] and the rupture of Plasmodium falciparum from host erythrocytes [52]. The simplicity of the method and the small sample requirements allow for the comparison of different time points, as well as the analysis of altered proteolytic processing in response to protease inhibition. Adding upstream subcellular fractionation steps to the workflow can assist in determining the cellular localization of proteolytic events. Similar to other gel-based approaches, limitations of the PROTOMAP technique include the fact that precise determination of proteolytic cleavage sites depends on sequence coverage and that the overall resolution of gel electrophoresis may be insufficient to detect small mass shifts.

Translating sequence specificity knowledge into cleavage assays

Gel-based and terminal proteomics approaches can only provide a limited view of the dynamics of proteolytic processing due to the finite number of time points that can be analyzed. In order to design or screen for novel protease inhibitors, solid kinetic information on proteolytic cleavage reactions is needed. Fluorescence-based cleavage assays that rely on the activation or dequenching of fluorophores upon proteolytic cleavage are the gold standard to measure kinetics of proteolytic reactions. Unlike the proteomics methodologies described above that are focused on discovery, cleavage assays require prior knowledge of the cleavage reactions, so peptide constructs can be synthesized that specifically report on substrate-to-product conversions. While cleavage assays perform well in typical in vitro experiments, potential overlapping substrate profiles make the analysis of complex proteolytic networks that encompass multiple enzymes challenging. Therefore, it is crucial to define the specificity of cleavage assays before they are employed to measure enzymatic activities in vivo.

Label-free protease assays are slowly becoming an alternative to fluorescence-based cleavage assays. For example, multiple-reaction monitoring (MRM) allows for the targeted quantification of peptides in complex biological matrices. MRM assays, typically performed on triple quadrupole instruments, determine peptide abundances by measuring the intensities of characteristic MS/MS fragment ions that provide strong, interference-free signals. Compared to other MS-techniques, MRM assays provide higher sensitivity and specificity and can be used in conjunction with stable isotope-labeled peptides for absolute quantitation [53]. Like other MS-based approaches, MRM-assays allow to simultaneously measure the abundances of multiple substrate and cleavage products. However, not unlike fluorescence-based assays, MRM experiments require considerable assay development effort upfront to optimize LC and MS conditions for each analyte. So far little of the potential that MRM assays could have in protease research has been realized. Notable exceptions are the utilization of MRM-assays to measure the abundances of vasoactive peptides in plasma in response to the injection of ACE-inhibitors [54] and the absolute quantitation of protease inhibitors in patient samples [55].

An interesting alternative method for the label-free monitoring of enzymatic reactions is MS-assisted enzyme screening (MES), in which endogenous proteases are captured from biological samples using functionalized beads. Captured enzymes are subsequently incubated with substrates, whose degradation fates are monitored by MS. By fractionating enzymes from the biological matrices, interfering compounds are removed and defined amounts and combinations of substrates can be used for the temporal analysis step [56]. Other methods for monitoring enzymatic reactions by MS have been reviewed by Liesener and Karst [57] and Schlüter et al. [58]. It is noteworthy to point out that label-free protease assays do not necessarily have to rely on MS, as shown by the recent development of a supramolecular tandem protease assay that relies on indicator-replacement technology [59].

Assessing proteolysis more directly with peptidomics workflows

Terminal proteomics and gel-based techniques are focused on the analysis of the proteolytic processing of large protein substrates. These workflows require additional experimental steps (e.g., tryptic digestion) that convert proteins to peptides that in turn can be detected and identified by MS/MS. However, large proteins are not the exclusive targets of proteolytic reactions, instead many proteases are specialized in processing biologically active peptides such as bradykinin, angiotensin and endothelin. Due to their smaller size, bioactive peptides are innately more suitable to MS-based analysis than proteins. Peptide extraction and sample processing workflows are simple and realized in a few steps, which allow for repeated data acquisition and a more direct measurement of the dynamic composition of the peptidome. Over the last decade, MS-based peptidomics studies have identified a vast repertoire of endogenous peptides and particular attention has been given to neuropeptides that participate as messenger molecules in many physiological processes [60, 61]. Relative abundances of peptides can be determined by a range of stable isotope tags including iTRAQ and other amine reactive labels [62–65] or by label-free approaches [66, 67]. By comparing differences in the peptidome in response to genetic knockouts or pharmaceutical inhibition of particular proteases, it is possible to define the endogenous substrate and cleavage product profiles of the enzymes [66, 68]. Given the correlation of aberrant proteolysis with many diseases [69], proteolytic profiles are also emerging as potential biomarkers. For example, Villanueva et al. identified peptide signatures that are indicative of cancer related proteolytic activities [70]. In these ex vivo experiments, endogenous and exogenous substrates are incubated with co-collected proteases for extended periods of time and MS is used to monitor cleavage products. The PALeO method (protease activity labeling employing 18O-enriched water) has been developed to increase the specificity of these peptidomics experiments by providing a distinctive signal against the complex background encountered in biological samples such as serum [71]. In a PALeO experiment, proteolytic reactions are carried out in the presence of 18O-enriched water. Peptide bond hydrolysis results in the concomitant incorporation of solvent 18O-atoms into the C-termini of nascent cleavage products. The characteristic 18O-isotope signature can readily be detected by MS allowing for the positive identification of cleavage products and the disregarding of background signals. We recently applied the PALeO-technique to survey in vivo targets of proteases in interstitial fluid collected from the microenvironment of oral cancers [72].

Interestingly, monitoring proteolytic reactions in the presence of H218O revealed that certain proteases (e.g., the serine protease trypsin) rebind cleavage products, which results in the incorporation of a second 18O-atom upon hydrolysis of the acyl-enzyme intermediate [73]. 18O-based strategies such as PALeO can therefore provide unique information about protease specificity. Since peptidomics studies focus only on the low-molecular weight fraction, their direct analytical approach can capture the dynamic aspects of these networks. To further improve quantitative measurements, non-degradable peptides (e.g., all D-amino acid peptides) can be included to serve as internal quantitation standards [74]. Furthermore, stable-isotopically labeled peptides can be used as defined protease substrates to track their degradation in complex mixtures.

Activity-based probes to assess protease activities

Instead of measuring the turnover of substrates, it is also possible to assess the proteolytic potential by directly measuring the activity states of proteases. Due to their physiological importance and the irreversible nature of their actions, the cellular activities of proteases are tightly regulated. Among the multilayered control mechanisms for proteolytic activities are zymogen activation, posttranslational modifications and the co-expression of endogenous protease inhibitors. Spatial (e.g., subcellular compartmentalization) and temporal distribution as well as chemical activation induced by ions or pH can also alter the net activity of proteases. As consequence of these regulatory mechanisms, measuring solely the overall abundance of a protease is a poor estimate of its actual biological activity. Furthermore, proteases are typically low abundant molecules, which hampers their identification and functional characterization. Zymograms are simple, sensitive and quantifiable assays for protease activities, in which proteins are separated by electrophoresis in gels containing co-polymerized substrates. After incubation, enzyme activities are revealed as clear bands against substrate backgrounds [75]. Zymography does not directly provide the identity of the detected enzyme activities. To this end activity-based probes (ABPs) have been developed, whose reactive groups are directed at the active sites of mechanistically related enzymes. ABPs have been developed for serine hydrolases, cysteine proteases, metallohydrolases, aspartyl proteases and the proteasome [76]. General design features of ABPs include a reactive group, a spacer or binding group and a reporter tag. A variety of reporter moieties can be used for visualization (e.g., fluorophores such as rhodamine) and enrichment (e.g., biotin) of probe-labeled enzymes. Enriched proteases are subsequently identified by MS-based workflows. Additional experimental flexibility can be achieved by the utilization of click chemistry-based alkyne- and azide tags that allow for the in vitro conjugation of reporter moieties after the profiling of in vivo protein activities [77]. The modular structure of ABPs makes them versatile tools to profile all major classes of proteases and utilize them in various experimental applications ranging from the discovery of protease inhibitors using competitive ABP-profiling [78] to biomarker discovery [79] and the real time monitoring of protease activities in living cells [80].

Moving beyond mass spectrometry: validation of proteolysis in vivo

Advances in mass spectrometry will help to shift the analytical focus of protease research from static to dynamic measurements and assist the transition from identification to activity-based workflows. However, as pointed out in the preceding paragraphs, there are limits to what can be achieved by MS-based technologies. Therefore, it is prudent to combine MS-based approaches with other analytical strategies that are better suited for the biochemical validation of proteolytic reactions in vivo. Classically, in vivo validation has been based on immunological assays [36, 37]. The adaptation of ABPs as tools for imaging enzyme activities in vivo can serve as role model for efforts that go beyond measuring basic aspects of proteolytic reactions. For example, optically quenched, near-infrared fluorescence imaging probes that are activated in situ by proteases, have been used to localize tumors [81]. Other milestone include the introduction of stable, non-cytotoxic, near-infrared fluorescent proteins [82] and recent work on nanoparticles that uses a mechanism called second harmonic generation to convert near-infrared light to visible light [83]. The development of these noninvasive imaging tools indicate that future in vivo protease activity probes may even move beyond fluorescence-based technology.

Conclusions and future directions

The holy grail of protease research is the study of the dynamics of proteolytic processes in situ. Activity-based MS technologies continue to play an integral part in achieving this goal. Some challenges however remain. For example, most quantitative MS strategies are limited to small sample numbers, which renders them less suitable to temporal studies. Targeted MRM-assays can increase throughput, but do so at the cost of the discovery research component. Currently, MS-based techniques are by themselves incapable of measuring proteolysis directly in living organisms. Therefore, careful integration with other technologies is necessary, as exemplified by the application of ABPs and other live imaging probes. The role of MS in such studies is likely to be at the front end, where target molecules are identified and their in vitro and ex vivo functional relationships are explored. For example, MS-based substrate discovery assays can be used to detect overlapping substrate specificities that are a common problem in the development of cleavage assays.

In order to make a meaningful contribution to the interdisciplinary protease research effort, it is crucial that the plethora of MS-data emerging from these experiments is properly compiled and disseminated. Web sites dedicated to protease research such as MEROPS (http://merops.sanger.ac.uk) [84], the Proteolysis Map (PMAP; [85]), the TopFIND knowledgebase (http://clipserve.clip.ubc.ca/topfind/) [86] and the Mammalian Degradome Database [87] are leading the way in this effort and already constitute valuable resources to investigators. Some of the challenges that these aggregators of protease information face are how to unify data acceptance criteria and reduce false-positive identifications. Standardizing the validation procedure will streamline the process of prioritizing biochemically important proteolytic events from background noise. It is foreseeable, how future iterations of these protease database compilations will incorporate kinetic information to differentiate, for example, the efficiency of cleavage sites. Such move from qualitative to quantitative analysis of proteolysis will help eliminate false-positive identifications, improve predictive algorithms and increase overall utility to the research community. Already, there are several promising tools that can predict cleavage sites for proteases such as caspases [88–91]. Accurate cleavage predictions would allow for the in silico design of fluorescence- and MRM-based cleavage assays. Likewise, it would be possible to “reverse analyze” proteolysis and use the presence of signature cleavage products to determine which protease is most likely to be responsible for an observed cleavage reaction. Such an approach would be an interesting methodology to detect the presence and activity of elusive, low-abundant proteases.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by a grant from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (R01 DE 019796) to Markus Hardt.

Standard abbreviations

- 1-D

one-dimensional

- 2-D

two-dimensional

- ABPs

activity-based probes

- COFRADIC

combined fractional diagonal chromatography

- ICAT

isotope-coded affinity tag

- iTRAQ

isobaric tag for relative and absolute quantitation

- LC

liquid chromatography

- MES

mass spectrometry-assisted enzyme screening

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinase

- MRM

multiple-reaction monitoring

- MS

mass spectrometry

- MS/MS

tandem mass spectrometry

- PALeO

protease activity labeling employing 18O-enriched water

- PMAP

proteolysis map

- PROTOMAP

protein topography and migration analysis platform

- SILAC

stable isotope labeling with amino acids in cell culture

Footnotes

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Gierasch LM, Gershenson A. Post-reductionist protein science, or putting Humpty Dumpty back together again. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:774–777. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Puente XS, Sánchez LM, Overall CM, López-Otín C. Human and mouse proteases: a comparative genomic approach. Nat Rev Genet. 2003;4:544–558. doi: 10.1038/nrg1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schechter I, Berger A. On the size of the active site in proteases. I. Papain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1967;27:157–162. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(67)80055-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diamond SL. Methods for mapping protease specificity. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2007;11:46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harris JL, Backes BJ, Leonetti F, Mahrus S, et al. Rapid and general profiling of protease specificity by using combinatorial fluorogenic substrate libraries. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:7754–7759. doi: 10.1073/pnas.140132697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Backes BJ, Harris JL, Leonetti F, Craik CS, Ellman JA. Synthesis of positional-scanning libraries of fluorogenic peptide substrates to define the extended substrate specificity of plasmin and thrombin. Nat Biotech. 2000;18:187–193. doi: 10.1038/72642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rano TA, Timkey T, Peterson EP, Rotonda J, et al. A combinatorial approach for determining protease specificities: application to interleukin-1beta converting enzyme (ICE) Chem Biol. 1997;4:149–155. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(97)90258-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salisbury CM, Maly DJ, Ellman JA. Peptide microarrays for the determination of protease substrate specificity. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:14868–14870. doi: 10.1021/ja027477q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turk BE. Mixture-based peptide libraries for identifying protease cleavage motifs. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;539:79–91. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-003-8_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matthews DJ, Wells JA. Substrate phage: selection of protease substrates by monovalent phage display. Science. 1993;260:1113–1117. doi: 10.1126/science.8493554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boulware KT, Daugherty PS. Protease specificity determination by using cellular libraries of peptide substrates (CLiPS) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:7583–7588. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511108103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schilling O, Overall CM. Proteome-derived, database-searchable peptide libraries for identifying protease cleavage sites. Nat Biotech. 2008;26:685–694. doi: 10.1038/nbt1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crooks G, Hon G, Chandonia J, Brenner S. WebLogo: a sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 2004;14:1188–1190. doi: 10.1101/gr.849004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Colaert N, Helsens K, Martens L, Vandekerckhove J, Gevaert K. Improved visualization of protein consensus sequences by iceLogo. Nat Methods. 2009;6:786–787. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1109-786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakazawa T, Yamaguchi M, Okamura TA, Ando E, et al. Terminal proteomics: N- and C-terminal analyses for high-fidelity identification of proteins using MS. Proteomics. 2008;8:673–685. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McDonald L, Robertson DHL, Hurst JL, Beynon RJ. Positional proteomics: selective recovery and analysis of N-terminal proteolytic peptides. Nat Methods. 2005;2:955–957. doi: 10.1038/nmeth811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Impens F, Colaert N, Helsens K, Plasman K, et al. MS-driven protease substrate degradomics. Proteomics. 2010;10:1284–1296. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200900418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schilling O, Overall CM. Proteomic discovery of protease substrates. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2007;11:36–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agard NJ, Wells JA. Methods for the proteomic identification of protease substrates. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2009;13:503–509. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu G, Shin SBY, Jaffrey SR. Global profiling of protease cleavage sites by chemoselective labeling of protein N-termini. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:19310–19315. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908958106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Timmer JC, Enoksson M, Wildfang E, Zhu W, et al. Profiling constitutive proteolytic events in vivo. Biochem J. 2007;407:41–48. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mahrus S, Trinidad JC, Barkan DT, Sali A, et al. Global sequencing of proteolytic cleavage sites in apoptosis by specific labeling of protein N termini. Cell. 2008;134:866–876. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mikami T, Takao T. Selective isolation of N-blocked peptides by isocyanate-coupled resin. Anal Chem. 2007;79:7910–7915. doi: 10.1021/ac071294a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McDonald L, Beynon RJ. Positional proteomics: preparation of amino-terminal peptides as a strategy for proteome simplification and characterization. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:1790–1798. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gevaert K, Goethals M, Martens L, van Damme J, et al. Exploring proteomes and analyzing protein processing by mass spectrometric identification of sorted N-terminal peptides. Nat Biotech. 2003;21:566–569. doi: 10.1038/nbt810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schilling O, Barré O, Huesgen PF, Overall CM. Proteome-wide analysis of protein carboxy termini: C terminomics. Nat Methods. 2010;7:508–511. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elias JE, Gygi SP. Target-decoy search strategy for increased confidence in large-scale protein identifications by mass spectrometry. Nat Methods. 2007;4:207–214. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keller A, Nesvizhskii AI, Kolker E, Aebersold R. Empirical statistical model to estimate the accuracy of peptide identifications made by MS/MS and database search. Anal Chem. 2002;74:5383–5392. doi: 10.1021/ac025747h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Helsens K, Timmerman E, Vandekerckhove J, Gevaert K, Martens L. Peptizer, a tool for assessing false positive Peptide identifications and manually validating selected results. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2008;7:2364–2372. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800082-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shteynberg D, Deutsch EW, Lam H, Eng JK, et al. iProphet: Multi-level integrative analysis of shotgun proteomic data improves peptide and protein identification rates and error estimates. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2011 doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.007690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deutsch EW, Mendoza L, Shteynberg D, Farrah T, et al. A guided tour of the Trans-Proteomic Pipeline. Proteomics. 2010;10:1150–1159. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200900375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kleifeld O, Doucet A, Auf dem Keller U, Prudova A, et al. Isotopic labeling of terminal amines in complex samples identifies protein N-termini and protease cleavage products. Nat Biotech. 2010;28:281–288. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xie F, Liu T, Qian WJ, Petyuk VA, Smith RD. Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry-based Quantitative Proteomics. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:25443–25449. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R110.199703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tam EM, Morrison CJ, Wu YI, Stack MS, Overall CM. Membrane protease proteomics: Isotope-coded affinity tag MS identification of undescribed MT1-matrix metalloproteinase substrates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:6917–6922. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305862101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dean RA, Butler GS, Hamma-Kourbali Y, Delbé J, et al. Identification of candidate angiogenic inhibitors processed by matrix metalloproteinase 2 (MMP-2) in cell-based proteomic screens: disruption of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)/heparin affin regulatory peptide (pleiotrophin) and VEGF/Connective tissue growth factor angiogenic inhibitory complexes by MMP-2 proteolysis. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:8454–8465. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00821-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Damme P, Martens L, van Damme J, Hugelier K, et al. Caspase-specific and nonspecific in vivo protein processing during Fas-induced apoptosis. Nat Methods. 2005;2:771–777. doi: 10.1038/nmeth792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Enoksson M, Li J, Ivancic MM, Timmer JC, et al. Identification of proteolytic cleavage sites by quantitative proteomics. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:2850–2858. doi: 10.1021/pr0701052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prudova A, Auf dem Keller U, Butler GS, Overall CM. Multiplex N-terminome analysis of MMP-2 and MMP-9 substrate degradomes by iTRAQ-TAILS quantitative proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2010;9:894–911. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M000050-MCP201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dean RA, Overall CM. Proteomics discovery of metalloproteinase substrates in the cellular context by iTRAQ labeling reveals a diverse MMP-2 substrate degradome. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2007;6:611–623. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600341-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ong SE, Blagoev B, Kratchmarova I, Kristensen DB, et al. Stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture, SILAC, as a simple and accurate approach to expression proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2002;1:376–386. doi: 10.1074/mcp.m200025-mcp200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gioia M, Foster LJ, Overall CM. Cell-based identification of natural substrates and cleavage sites for extracellular proteases by SILAC proteomics. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;539:131–153. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-003-8_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van Damme P, Maurer-Stroh S, Plasman K, van Durme J, et al. Analysis of protein processing by N-terminal proteomics reveals novel species-specific substrate determinants of granzyme B orthologs. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2009;8:258–272. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800060-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Plasman K, van Damme P, Kaiserman D, Impens F, et al. Probing the efficiency of proteolytic events by positional proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2011;10:M110.003301. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M110.003301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gupta N, Hixson KK, Culley DE, Smith RD, Pevzner PA. Analyzing protease specificity and detecting in vivo proteolytic events using tandem mass spectrometry. Proteomics. 2010;10:2833–2844. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200900821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xu D, Suenaga N, Edelmann MJ, Fridman R, et al. Novel MMP-9 substrates in cancer cells revealed by a label-free quantitative proteomics approach. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2008;7:2215–2228. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800095-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guo L, Eisenman JR, Mahimkar RM, Peschon JJ, et al. A proteomic approach for the identification of cell-surface proteins shed by metalloproteases. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2002;1:30–36. doi: 10.1074/mcp.m100020-mcp200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ambort D, Stalder D, Lottaz D, Huguenin M, et al. A novel 2D-based approach to the discovery of candidate substrates for the metalloendopeptidase meprin. FEBS J. 2008;275:4490–4509. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee AY, Park BC, Jang M, Cho S, et al. Identification of caspase-3 degradome by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight analysis. Proteomics. 2004;4:3429–3436. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200400979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bredemeyer AJ, Lewis RM, Malone JP, Davis AE, et al. A proteomic approach for the discovery of protease substrates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:11785–11790. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402353101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Timmer JC, Zhu W, Pop C, Regan T, et al. Structural and kinetic determinants of protease substrates. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dix MM, Simon GM, Cravatt BF. Global mapping of the topography and magnitude of proteolytic events in apoptosis. Cell. 2008;134:679–691. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bowyer PW, Simon GM, Cravatt BF, Bogyo M. Global profiling of proteolysis during rupture of Plasmodium falciparum from the host erythrocyte. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2011;10:M110.001636. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M110.001636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Domon B, Aebersold R. Options and considerations when selecting a quantitative proteomics strategy. Nat Biotech. 2010;28:710–721. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lortie M, Bark S, Blantz R, Hook V. Detecting low-abundance vasoactive peptides in plasma: progress toward absolute quantitation using nano liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Anal Biochem. 2009;394:164–170. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2009.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lu S, Jiang K, Qin F, Lu X, Li F. Simultaneous quantification of enalapril and enalaprilat in human plasma by high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry and its application in a pharmacokinetic study. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2009;49:163–167. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2008.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schlüter H, Jankowski J, Rykl J, Thiemann J, et al. Detection of protease activities with the mass-spectrometry-assisted enzyme-screening (MES) system. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2003;377:1102–1107. doi: 10.1007/s00216-003-2211-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liesener A, Karst U. Monitoring enzymatic conversions by mass spectrometry: a critical review. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2005;382:1451–1464. doi: 10.1007/s00216-005-3305-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schlüter H, Hildebrand D, Gallin C, Schulz A, et al. Mass spectrometry for monitoring protease reactions. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2008;392:783–792. doi: 10.1007/s00216-008-2213-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ghale G, Ramalingam V, Urbach AR, Nau WM. Determining protease substrate selectivity and inhibition by label-free supramolecular tandem enzyme assays. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:7528–7535. doi: 10.1021/ja2013467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hummon AB, Amare A, Sweedler JV. Discovering new invertebrate neuropeptides using mass spectrometry. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2006;25:77–98. doi: 10.1002/mas.20055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fricker LD, Lim J, Pan H, Che FY. Peptidomics: identification and quantification of endogenous peptides in neuroendocrine tissues. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2006;25:327–344. doi: 10.1002/mas.20079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Che FY, Fricker LD. Quantitative peptidomics of mouse pituitary: comparison of different stable isotopic tags. J Mass Spectrom. 2005;40:238–249. doi: 10.1002/jms.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wardman JH, Zhang X, Gagnon S, Castro LM, et al. Analysis of peptides in prohormone convertase 1/3 null mouse brain using quantitative peptidomics. J Neurochem. 2010;114:215–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06760.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hardt M, Witkowska HE, Webb S, Thomas LR, et al. Assessing the effects of diurnal variation on the composition of human parotid saliva: quantitative analysis of native peptides using iTRAQ reagents. Anal Chem. 2005;77:4947–4954. doi: 10.1021/ac050161r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brockmann A, Annangudi SP, Richmond TA, Ament SA, et al. Quantitative peptidomics reveal brain peptide signatures of behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:2383–2388. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813021106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tagore DM, Nolte WM, Neveu JM, Rangel R, et al. Peptidase substrates via global peptide profiling. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:23–25. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Quintana LF, Campistol JM, Alcolea MP, Bañon-Maneus E, et al. Application of label-free quantitative peptidomics for the identification of urinary biomarkers of kidney chronic allograft dysfunction. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2009;8:1658–1673. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M900059-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tinoco AD, Kim YG, Tagore DM, Wiwczar J, et al. A peptidomics strategy to elucidate the proteolytic pathways that inactivate Peptide hormones. Biochemistry. 2011;50:2213–2222. doi: 10.1021/bi2000033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.López-Otín C, Bond JS. Proteases: multifunctional enzymes in life and disease. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:30433–30437. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800035200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Villanueva J, Shaffer DR, Philip J, Chaparro CA, et al. Differential exoprotease activities confer tumor-specific serum peptidome patterns. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:271–284. doi: 10.1172/JCI26022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Robinson S, Niles RK, Witkowska HE, Rittenbach KJ, et al. A mass spectrometry-based strategy for detecting and characterizing endogenous proteinase activities in complex biological samples. Proteomics. 2008;8:435–445. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hardt M, Lam D, Dolan J, Schmidt B. Surveying proteolytic processes in human cancer microenvironments by microdialysis and activity-based mass spectrometry. Protomics Clin Appl. 2011;5:636–643. doi: 10.1002/prca.201100015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yao X, Afonso C, Fenselau C. Dissection of proteolytic 18O labeling: endoprotease-catalyzed 16O-to-18O exchange of truncated peptide substrates. J Proteome Res. 2003;2:147–152. doi: 10.1021/pr025572s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Villanueva J, Nazarian A, Lawlor K, Tempst P. Monitoring peptidase activities in complex proteomes by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:1167–1183. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Leber TM, Balkwill FR. Zymography: A Single-Step Staining Method for Quantitation of Proteolytic Activity on Substrate Gels. Anal Biochem. 1997;249:24–28. doi: 10.1006/abio.1997.2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cravatt BF, Wright A, Kozarich J. Activity-based protein profiling: from enzyme chemistry to proteomic chemistry. Annu Rev Biochem. 2008;77:383–414. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.101304.124125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Speers AE, Cravatt BF. Profiling enzyme activities in vivo using click chemistry methods. Chem Biol. 2004;11:535–546. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Leung D, Hardouin C, Boger DL, Cravatt BF. Discovering potent and selective reversible inhibitors of enzymes in complex proteomes. Nat Biotech. 2003;21:687–691. doi: 10.1038/nbt826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jessani N, Humphrey M, McDonald WH, Niessen S, et al. Carcinoma and stromal enzyme activity profiles associated with breast tumor growth in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:13756–13761. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404727101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Blum G, von Degenfeld G, Merchant MJ, Blau HM, Bogyo M. Noninvasive optical imaging of cysteine protease activity using fluorescently quenched activity-based probes. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:668–677. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Weissleder R, Tung CH, Mahmood U, Bogdanov A. In vivo imaging of tumors with protease-activated near-infrared fluorescent probes. Nat Biotech. 1999;17:375–378. doi: 10.1038/7933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Filonov GS, Piatkevich KD, Ting LM, Zhang J, et al. Bright and stable near-infrared fluorescent protein for in vivo imaging. Nat Biotech. 2011;8:703–704. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cohen BE. Biological imaging: Beyond fluorescence. Nature. 2010;467:407–408. doi: 10.1038/467407a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rawlings ND, Barrett AJ, Bateman A. MEROPS: the peptidase database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D227–233. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Igarashi Y, Heureux E, Doctor KS, Talwar P, et al. PMAP: databases for analyzing proteolytic events and pathways. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D611–618. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lange PF, Overall CM. TopFIND, a knowledgebase linking protein termini with function. Nat Methods. 2011;8:703–704. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Quesada V, Ordóñez GR, Sánchez LM, Puente XS, López-Otín C. The Degradome database: mammalian proteases and diseases of proteolysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D239–243. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Boyd SE, Pike RN, Rudy GB, Whisstock JC, Garcia de la Banda M. PoPS: a computational tool for modeling and predicting protease specificity. J Bioinform Comput Biol. 2005;3:551–585. doi: 10.1142/s021972000500117x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lohmuller T, Wenzler D, Hagemann S, Kiess W, et al. Toward computer-based cleavage site prediction of cysteine endopeptidases. Biol Chem. 2003;384:899–909. doi: 10.1515/BC.2003.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Garay-Malpartida HM, Occhiucci JM, Alves J, Belizário JE. CaSPredictor: a new computer-based tool for caspase substrate prediction. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(Suppl 1):i169–176. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Song J, Tan H, Shen H, Mahmood K, et al. Cascleave: towards more accurate prediction of caspase substrate cleavage sites. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:752–760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]