Abstract

OBJECTIVES: Forty percent of women with ovarian carcinoma have circulating free neoplastic DNA identified in plasma. Angiogenesis is critical in neoplastic growth and metastasis. We sought to determine whether circulating neoplastic DNA results from alterations in the balance of angiogenesis activators and inhibitors. METHODS: Sixty patients with invasive ovarian carcinomas with somatic TP53 mutations that had been characterized for circulating neoplastic DNA had carcinoma analyzed for microvessel density using immunohistochemistry with CD31 and for the expression of VEGF, ANGPT1, ANGPT2, PTGS2, PLAU, THBS1, CSF1, PIK3CA, HIF1A, IL8, MMP2, and MMP9 message by real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction. The expression of each gene was calculated relative to GAPDH expression for each neoplasm. Patient plasma had been tested for circulating neoplastic DNA using a ligase detection reaction. RESULTS: MMP2 expression was significantly correlated with free plasma neoplastic DNA (P = .007). Microvessel density was not correlated with plasma neoplastic DNA or BRCA1/2 mutation status. The expression pattern of other angiogenic factors did not correlate with plasma neoplastic DNA but correlated with each other. BRCA1/2 mutated carcinomas had significantly different expression profiles of angiogenesis activators and inhibitors in comparison to sporadic carcinomas. CONCLUSIONS: MMP2 expression is associated with the presence of circulating neoplastic DNA in women with ovarian carcinoma. These data are consistent with the proinvasive properties of MMP2 and suggest that the presence of circulating neoplastic DNA indicates a more aggressive malignant phenotype. Carcinomas with germ line BRCA1/2 mutations had a lower angiogenic profile than those without mutations.

Introduction

Ovarian carcinoma is the most common cause of death among women with a gynecologic cancer in the United States [1]. Most women present with an advanced stage of disease and have lymph node or intraperitoneal metastasis at the time of diagnosis. The 5-year survival for advanced-stage disease (i.e., stage III–IV) ranges from 18% to 40% [2].

Circulating cell-free neoplastic DNA has been identified in the plasma of 17% to 44% of patients with ovarian carcinoma [3–5]. The origin of neoplastic DNA in the circulation is unknown. Several hypotheses have been advanced to explain this phenomenon, including lysis of circulating neoplastic cells or micrometastases, tumor necrosis, apoptosis, or spontaneous active release of DNA by the malignancy into the bloodstream [6]. The presence of free neoplastic DNA in the plasma of women with ovarian carcinoma has been linked to poor outcome and diminished survival [3,4,7,8].

The pattern of metastases in ovarian, peritoneal, and fallopian tube carcinoma is different from that of other solid malignancies. Ovarian carcinomas spread predominantly by direct dissemination in the peritoneal cavity or through local lymphatic channels and rarely by hematogenous spread [9]. The role of various proinvasive proteolytic enzymes and angiogenesis activators and inhibitors has been studied in ovarian carcinomas, including matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), a large family of zinc-dependant endopeptidases capable of degrading extracellular matrix and basement membrane components [10]. MMPs have been implicated in neoplastic growth, invasion, and metastasis [11,12]. Expression of MMP2, a protease responsible for the control of various collagens (including the degradation of type IV collagen) that make up the extracellular matrix, is elevated in ovarian carcinoma compared to borderline or benign ovarian neoplasms, suggesting a role in carcinogenesis [13,14]. Overexpression of MMP2 in neoplastic cells of peritoneal implants in ovarian cancer patients has been associated with an increased risk of death [13].

Angiogenesis is also critical in neoplastic growth and metastasis. VEGF is a cytokine that functions to increase microvascular permeability and stimulate endothelial cell growth and angiogenesis [15,16]. Increased production of VEGF has been implicated in tumorigenesis, metastasis, and the production of malignant effusions by increasing vascular permeability [16,17]. Rudlowski et al. [18] associated enhanced VEGF expression in ovarian carcinoma ascites with reduced progression-free and overall survival. Increased microvessel density (MVD), another marker of angiogenesis, is also associated with worse prognosis in most studies in ovarian carcinomas [19].

We sought to determine whether the presence of circulating neoplastic DNA is associated with alterations in the balance of angiogenesis activators and inhibitors in ovarian carcinoma. In addition, we correlated the expression of angiogenesis genes in the carcinoma with the presence of germ line BRCA1 and BRCA2 (BRCA1/2) mutations to assess for possible differences among this cohort. There have been many studies that report improved survival in patients with BRCA1/2-associated ovarian carcinoma in comparison to patients with sporadic ovarian carcinoma [20–24]. We wanted to assess the angiogenic profile in BRCA1/2-mutated carcinomas that might explain a potential survival advantage and afford insight into possible treatment strategies.

Materials and Methods

Patients and Specimens

Blood, neoplastic tissue, clinical information, and follow-up data were collected by the University of Washington Gynecologic Oncology Tissue Bank as approved by the Human Subjects Committee of the Institutional Review Board. Ovarian carcinomas that had been previously sequenced for somatic TP53 mutations and characterized for circulating neoplastic DNA were identified. Platinum resistance was defined as less-than-a-complete response to chemotherapy or relapse within 6 months of completing chemotherapy. Carcinomas were surgically staged according to the International Federation of Obstetrics and Gynecology (FIGO) criteria [25]. Optimal surgical debulking was defined as no residual neoplasm greater than 1 cm in diameter. Overall survival was defined as the interval between diagnosis and death or diagnosis and last observation. Data were censored at the last follow-up. BRCA1/2 mutations were characterized using targeted selection and massively parallel genomic sequencing as previously reported [26].

DNA Sequencing and Ligase Detection Reaction

DNA had previously been extracted using the QIAamp DNA Mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) as previously described, and plasma DNA was quantified after extraction with the PicoGreen dsDNA Quantification Kit (Molecular Probes, Inc, Eugene, OR) [3,27]. Sequencing using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplified for all TP53 coding exons (4–10) and flanking regulatory regions had also been performed. Finally, the sensitive ligase detection reaction previously reported was used to evaluate the target TP53 sequence [3].

Immunohistochemistry

Sixty ovarian carcinomas were analyzed for MVD using immunohistochemistry with CD31 as previously described [19]. MVD at 400x magnification was stratified into high (>15 vessels/high-power field) versus low (≤15 vessels/high-power field) counts.

Angiogenic Marker Expression

Quantitative messenger RNA expression of VEGF, ANGPT1, ANGPT2, PTSG2, PLAU, THBS1, CSF1, HIF1A, IL8, MMP2, and MMP9 was assessed using real-time quantitative reverse transcription-PCR. Reverse transcription-PCR was performed using complementary DNA, TaqMan probes (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA), and the TaqMan Universal PCR Kit (Applied Biosystems) and run on the ABI Prism7900 sequence detection system(Applied Biosystems). Expression was calculated relative to GAPDH expression for each neoplasm.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with StatView (SAS, Cary, NC) and Prism 4 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Contingency tables were evaluated with Fisher exact test or Pearson χ2 test. Two-sided Student's t test with P < .05 was used to determine statistical significance, and the Cox proportional hazards model was used for multivariate analysis. Overall survival was calculated according to the methods of Kaplan and Meier.

Results

Study Population

Sixty patients with ovarian carcinoma were identified with known somatic TP53 mutations. Characteristics of the study subjects are detailed in Table 1. Twenty-three patients (38.3%) had free neoplastic DNA identified in plasma using the ligase chain reaction for their specific somatic TP53 mutation as previously reported [3]. Nine patients (14.8%) had identified germ line BRCA1/2 mutations (four BRCA1 and five BRCA2).

Table 1.

Case Characteristics.

| Characteristics | Total (N = 60) | Plasma DNA+ (n = 23) | Plasma DNA- (n = 37) |

| Age, years | |||

| Median | 57 | 55 | 64 |

| Range | 28–88 | 28–88 | 37–88 |

| Survival, months | |||

| Mean | 39 | 35 | 39 |

| Range | 1–118 | 1–89 | 4–118 |

| FIGO stage, n (%) | |||

| I | 2 (3.3) | 0 | 2 (5.4) |

| II | 1 (1.7) | 1 (4.3) | 0 |

| III | 48 (80) | 17 (73.9) | 31 (83.8) |

| IV | 9 (15) | 5 (21.7) | 4 (10.8) |

| Histologic diagnosis, n (%) | |||

| Serous | 42 (70) | 14 (60.9) | 28 (75.7) |

| Adenocarcinoma NOS | 11 (18.3) | 5 (21.7) | 6 (16.2) |

| Clear cell | 1 (1.7) | 0 | 1 (2.7) |

| Endometrioid | 2 (3.3) | 1 (4.3) | 1 (2.7) |

| Carcinosarcoma | 2 (3.3) | 2 (8.7) | 0 |

| Other | 2 (3.3) | 1 (4.3) | 1 (2.7) |

| Grade, n (%) | |||

| 1 | 1 (1.7) | 0 | 1 (2.7) |

| 2 | 1 (1.7) | 1 (4.3) | 0 |

| 3 | 58 (96.7) | 22 (95.6) | 36 (97.3) |

| Optimal, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 32 (53.3) | 15 (65.2) | 18 (48.6) |

| No | 28 (46.7) | 8 (34.8) | 19 (51.4) |

| TP53 mutation, n (%) | |||

| Missense | 44 (73.3) | 17 (73.9) | 27 (73) |

| Null | 15 (25) | 5 (21.7) | 10 (27) |

| Splice | 1 (1.7) | 1 (4.3) | 0 |

| BRCA1/2 mutation, n (%) | |||

| Total | 9 (14.8) | 6 (26.1) | 3 (8.1) |

| BRCA1 | 4 (6.7) | 3 (13.0) | 1 (2.7) |

| BRCA2 | 5 (8.3) | 3 (13.0) | 2 (5.4) |

Most patients had advanced-stage disease, 80% presenting with stage III. Most subjects (97%) had grade 3 carcinomas and serous histologic diagnosis (70%). Slightly more than half (53%) were optimally debulked. All but three patients received adjuvant chemotherapy. Of those receiving chemotherapy, 54 patients (90%) received a platinum-taxane combination. One patient had an unknown chemotherapeutic regimen. Of the three who did not receive adjuvant therapy, one had stage IA and two refused (one with stage IIIB and one with stage IIIC disease). All patients had a preoperative CA-125 level greater than 35 U/ml.

Association of Neoplastic DNA in Plasma and Known Prognostic Factors

The presence of neoplastic plasma DNA was not associated with known prognostic factors including BRCA1/2 mutation status, lymph node metastasis (odds ratio = 0.70, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.24–2.04, P = .59), stage IV disease (OR = 2.48, 95% CI = 0.63–9.73, P = .30), suboptimal cytoreduction (OR = 0.64, 95% CI = 0.29–1.44, P = .32), or platinum resistance (37% vs 43%, P = .78). However, there was a borderline association of detectable circulating neoplastic DNA and the likelihood of complete response to initial chemotherapy (86% vs 61%, P = .07). Two patients (8.7%) with circulating neoplastic DNA developed brain metastases versus one patient (2.7%) in the group without free neoplastic DNA. Whereas the association of circulating neoplastic DNA and brain metastases was not statistically significant (P = .57, OR = 2.97, 95% CI = 0.26–34.26), the incidence in both groups exceeded that predicted for ovarian cancer (<1%).

Association of Angiogenesis Activators and Inhibitors with Circulating Neoplastic DNA

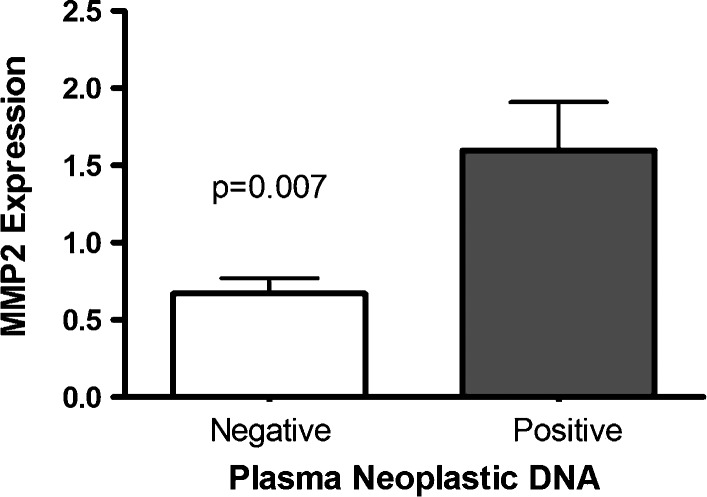

MMP2 expression was significantly correlated with circulating neoplastic DNA in plasma (P = .007; Figure 1). The expression of other angiogenic factors did not correlate with plasma neoplastic DNA but did significantly correlate with one another. Expression of MMP2 was thus significantly associated with expression of MMP9 and other angiogenesis activators. Expression of the various angiogenesis activators and inhibitors was not associated with MVD, and MVD was not associated with the presence of neoplastic DNA in plasma or BRCA1/2 mutation status. Increased MVD did not correlate with overall survival.

Figure 1.

Relative MMP2 expression in ovarian carcinomas was significantly higher in women with circulating neoplastic DNA compared to those without detectable circulating neoplastic DNA.

Carcinomas with Germ Line BRCA1/2 Mutations Have a Different Expression Profile of Angiogenesis Activators and Inhibitors

Ovarian carcinomas with known germ line BRCA1/2 mutations had expression profiles of angiogenesis activators that differed significantly from those of neoplasms without these mutations. Relative expression of the following proangiogenesis modulators was decreased in carcinomas with BRCA1/2 mutations: VEGF (P = .008), PLAU (P = .01), and CSF1 (P = .008) (Figure 2). The relative expression of the proangiogenesis factors MMP2 (P = .09), MMP9 (P = .21), PTGS2 (P = .06), and IL8 (P = .09) was also decreased in BRCA1/2-positive neoplasms, but the findings did not reach statistical significance. In further analysis of angiogenesis activators and inhibitors in BRCA1/2-mutated carcinomas, the relative expression of VEGF was significantly decreased in BRCA2 carcinomas in comparison to those with BRCA1 mutations (P = .03). One case had a somatic BRCA1 mutation (3593 delT) and had a higher angiogenic profile consistent with the wild-type sporadic carcinomas.

Figure 2.

Expression of proangiogenesis modulators in sporadic ovarian carcinomas compared to those with germ line BRCA1/2 mutations. (A) Relative VEGF expression was significantly lower in cases with BRCA1/2 mutations. (B) Relative PLAU expression was significantly lower in cases with BRCA1/2 mutations. (C) Relative CSF1 expression was significantly lower in cases with BRCA1/2 mutations.

Discussion

In our series, increased MMP2 expression was associated with circulating neoplastic DNA in plasma, consistent with our hypothesis that specific angiogenesis factors would influence the presence of circulating, cell-free neoplastic DNA and result in a more aggressive malignant phenotype. Modulators of MMP2 expression such as MMP14, TIMP2, and MMP7 are upregulated in ovarian carcinomas, as is MMP2 expression itself [14,28]. MMP2 cleavage of extracellular matrix proteins is believed to enhance adhesion of malignant cells to the peritoneum and thereby promote metastasis and invasion [29]. MMP2 overexpression has been correlated with elevated histologic grade and advanced stage in ovarian carcinoma and is thus considered a potential marker for proliferation, invasiveness, and metastasis [30]. Although several studies have suggested that overexpression of MMP2 in ovarian carcinoma is associated with poor survival, we did not detect a significant difference in survival among patients with a high expression of MMP2, but this was too small a cohort to detect moderate survival effects [13,31,32].

We and others have previously demonstrated that circulating tumor-derived DNA in the plasma of women with ovarian carcinoma portends for worse overall survival [3,4,7]. The current literature also suggests that cell-free neoplastic DNA may be associated with decreased progression-free survival and poor response to chemotherapy, in particular if elevated levels are detected after the initial treatment [8]. In accordance with that observed in the literature, 38.3% of our cohort had circulating neoplastic DNA identified in plasma. These patients did not demonstrate increased incidence of lymph node metastasis, stage IV disease, or suboptimal cytoreduction. In our cohort, there were three patients who developed brain metastasis, and although the results did not reach statistical significance, the incidence of brain metastasis (8.7%) was tripled in women with detectable cell-free neoplastic DNA in plasma, suggesting that cases with free neoplastic DNA in plasma may exhibit more hematogenous spread. We suggest that increased MMP2 expression may be the common link underlying worse prognosis and more aggressive spread patterns in cases with circulating neoplastic DNA.

Although MMP2 expression correlated with circulating neoplastic DNA, the expression of other angiogenesis activators did not. The expression of all the angiogenic factors did correlate highly with each other, and in carcinomas with high levels of MMP2 activity, levels of the various other angiogenic factors were also elevated. These data suggest that an aggressive malignant phenotype is mediated through a complex interplay of proteolytic enzymes and angiogenesis-promoting growth factors but that MMP2 may be the driving force that allows neoplastic DNA into the circulation.

Interestingly, ovarian carcinomas with germ line BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations have a lower expression profile of angiogenesis activators. Levels of VEGF, PLAU, and CSF1 were all significantly lower in carcinomas from women with germ line BRCA1/2 mutations, and there was a trend toward lower values of all other studied angiogenesis activators, including MMP2. These data are the first report of decreased expression of angiogenesis-promoting growth factors and proinvasive proteolytic enzymes in ovarian carcinomas associated with germ line BRCA1/2 mutations. Interestingly, the one case with a somatic BRCA1 mutation had a higher angiogenic profile, suggesting that germ line and somatic BRCA1/2 mutations may not be equivalent in relation to an angiogenic phenotype. In comparing BRCA1 and BRCA2 carcinomas, VEGF expression was significantly lower in BRCA2-mutated cases. A recent analysis by Bolton et al. [20], demonstrates improved survival in patients with BRCA1/2 carcinomas compared to sporadic controls with the best prognosis for women with BRCA2 mutations. Other smaller studies have reported similar findings [21–24]. Most authors have attributed increased survival in women with BRCA1/2-mutated ovarian carcinoma to improved response to platinum-based therapy; a less angiogenic phenotype could represent an alternative or supplementary explanation. The decreased level of VEGF expression in ovarian carcinomas with germ line BRCA2 mutations could contribute to a less aggressive phenotype in this subgroup. The number of BRCA1/2-mutated carcinomas in our cohort was small (nine patients), and these findings should be confirmed in a larger cohort as they could have therapeutic implications with regard to the use of angiogenesis inhibitors in different patient subsets.

In conclusion, our data suggest that cell-free neoplastic DNA gains access to plasma at least in part due to MMP2 overexpression. MMP2 overexpression, in addition to circulating neoplastic DNA, may thus be a marker for a more aggressive neoplastic phenotype. Levels of various angiogenesis activators were diminished in carcinomas with germ line BRCA1/2 mutations and may thus indicate a less aggressive phenotype, although this warrants verification in a larger patient cohort.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Ovarian Cancer Research Foundation, the National Institutes of Health (grant R01CA131965), and the Wendy Feuer Ovarian Cancer Research Fund.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Ward E, Brawley O, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2011: the impact of eliminating socioeconomic and racial disparities on premature cancer deaths. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:212–236. doi: 10.3322/caac.20121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holschneider CH, Berek JS. Ovarian cancer: epidemiology, biology, and prognostic factors. Semin Surg Oncol. 2000;19:3–10. doi: 10.1002/1098-2388(200007/08)19:1<3::aid-ssu2>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Swisher EM, Wollan M, Mahtani SM, Willner JB, Garcia R, Goff BA, King MC. Tumor-specific p53 sequences in blood and peritoneal fluid of women with epithelial ovarian cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:662–667. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dobrzycka B, Terlikowski SJ, Kinalski M, Kowalczuk O, Niklinska W, Chyczewski L. Circulating free DNA and p53 antibodies in plasma of patients with ovarian epithelial cancers. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:1133–1140. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Otsuka J, Okuda T, Sekizawa A, Amemiya S, Saito H, Okai T, Kushima M. Detection of p53 mutations in the plasma DNA of patients with ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2004;14:459–464. doi: 10.1111/j.1048-891x.2004.014305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stroun M, Maurice P, Vasioukhin V, Lyautey J, Lederrey C, Lefort F, Rossier A, Chen XQ, Anker P. The origin and mechanism of circulating DNA. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;906:161–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamat AA, Baldwin M, Urbauer D, Dang D, Han LY, Godwin A, Karlan BY, Simpson JL, Gershenson DM, Coleman RL, et al. Plasma cell-free DNA in ovarian cancer: an independent prognostic biomarker. Cancer. 2010;116:1918–1925. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Capizzi E, Gabusi E, Grigioni AD, De Iaco P, Rosati M, Zamagni C, Fiorentino M. Quantification of free plasma DNA before and after chemotherapy in patients with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer. Diagn Mol Pathol. 2008;17:34–38. doi: 10.1097/PDM.0b013e3181359e1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pickel H, Lahousen M, Stettner H, Girardi F. The spread of ovarian cancer. Baillieres Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 1989;3:3–12. doi: 10.1016/s0950-3552(89)80036-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Overall CM, Kleifeld O. Tumour microenvironment—opinion: validating matrix metalloproteinases as drug targets and anti-targets for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:227–239. doi: 10.1038/nrc1821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nelson AR, Fingleton B, Rothenberg ML, Matrisian LM. Matrix metalloproteinases: biologic activity and clinical implications. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:1135–1149. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.5.1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vihinen P, Kahari VM. Matrix metalloproteinases in cancer: prognostic markers and therapeutic targets. Int J Cancer. 2002;99:157–166. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perigny M, Bairati I, Harvey I, Beauchemin M, Harel F, Plante M, Tetu B. Role of immunohistochemical overexpression of matrix metalloproteinases MMP-2 and MMP-11 in the prognosis of death by ovarian cancer. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:226–231. doi: 10.1309/49LA9XCBGWJ8F2KM. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sakata K, Shigemasa K, Nagai N, Ohama K. Expression of matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-2, MMP-9, MT1-MMP) and their inhibitors (TIMP-1, TIMP-2) in common epithelial tumors of the ovary. Int J Oncol. 2000;17:673–681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Senger DR, Van de Water L, Brown LF, Nagy JA, Yeo KT, Yeo TK, Berse B, Jackman RW, Dvorak AM, Dvorak HF. Vascular permeability factor (VPF, VEGF) in tumor biology. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1993;12:303–324. doi: 10.1007/BF00665960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagy JA, Masse EM, Herzberg KT, Meyers MS, Yeo KT, Yeo TK, Sioussat TM, Dvorak HF. Pathogenesis of ascites tumor growth: vascular permeability factor, vascular hyperpermeability, and ascites fluid accumulation. Cancer Res. 1995;55:360–368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferrara N. Vascular endothelial growth factor. Eur J Cancer. 1996;32A:2413–2422. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(96)00387-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rudlowski C, Pickart AK, Fuhljahn C, Friepoertner T, Schlehe B, Biesterfeld S, Schroeder W. Prognostic significance of vascular endothelial growth factor expression in ovarian cancer patients: a long-term follow-up. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006;16(suppl 1):183–189. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2006.00307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rubatt JM, Darcy KM, Hutson A, Bean SM, Havrilesky LJ, Grace LA, Berchuck A, Secord AA. Independent prognostic relevance of microvessel density in advanced epithelial ovarian cancer and associations between CD31, CD105, p53 status, and angiogenic marker expression: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;112:469–474. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bolton KL, Chenevix-Trench G, Goh C, Sadetzki S, Ramus SJ, Karlan BY, Lambrechts D, Despierre E, Barrowdale D, McGuffog L, et al. Association between BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations and survival in women with invasive epithelial ovarian cancer. JAMA. 2012;307:382–390. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang D, Khan S, Sun Y, Hess K, Shmulevich I, Sood AK, Zhang W. Association of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations with survival, chemotherapy sensitivity, and gene mutator phenotype in patients with ovarian cancer. JAMA. 2011;306:1557–1565. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chetrit A, Hirsh-Yechezkel G, Ben-David Y, Lubin F, Friedman E, Sadetzki S. Effect of BRCA1/2 mutations on long-term survival of patients with invasive ovarian cancer: the national Israeli study of ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:20–25. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.6905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cass I, Baldwin RL, Varkey T, Moslehi R, Narod SA, Karlan BY. Improved survival in women with BRCA-associated ovarian carcinoma. Cancer. 2003;97:2187–2195. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boyd J, Sonoda Y, Federici MG, Bogomolniy F, Rhei E, Maresco DL, Saigo PE, Almadrones LA, Barakat RR, Brown CL, et al. Clinicopathologic features of BRCA-linked and sporadic ovarian cancer. JAMA. 2000;283:2260–2265. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.17.2260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pecorelli S, Benedet JL, Creasman WT, Shepherd JH. FIGO staging of gynecologic cancer. 1994–1997 FIGO Committee on Gynecologic Oncology. International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1999;65:243–249. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(99)00070-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walsh T, Casadei S, Lee MK, Pennil CC, Nord AS, Thornton AM, Roeb W, Agnew KJ, Stray SM, Wickramanayake A, et al. Mutations in 12 genes for inherited ovarian, fallopian tube, and peritoneal carcinoma identified by massively parallel sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:18032–18037. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115052108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sozzi G, Conte D, Mariani L, Lo Vullo S, Roz L, Lombardo C, Pierotti MA, Tavecchio L. Analysis of circulating tumor DNA in plasma at diagnosis and during follow-up of lung cancer patients. Cancer Res. 2001;61:4675–4678. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang FQ, So J, Reierstad S, Fishman DA. Matrilysin (MMP-7) promotes invasion of ovarian cancer cells by activation of progelatinase. Int J Cancer. 2005;114:19–31. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kenny HA, Lengyel E. MMP-2 functions as an early response protein in ovarian cancer metastasis. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:683–688. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.5.7703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kamel H, Abdelazim I, Habib SM, El Shourbagy MA, Ahmed NS. Immunoexpression of matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) in malignant ovarian epithelial tumours. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2010;32:580–586. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)34527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davidson B, Goldberg I, Gotlieb WH, Kopolovic J, Ben-Baruch G, Nesland JM, Berner A, Bryne M, Reich R. High levels of MMP-2, MMP-9, MT1-MMP and TIMP-2 mRNA correlate with poor survival in ovarian carcinoma. Clin Exp Metastasis. 1999;17:799–808. doi: 10.1023/a:1006723011835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu X, Li H, Kang L, Li L, Wang W, Shan B. Activated matrix metalloproteinase-2—a potential marker of prognosis for epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2002;84:126–134. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2001.6477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]