Abstract

Toll like receptors (TLRs) recognize specific microbial products and elicit innate immune signals to activate specific transcription factors that induce protective proteins, such as interferon. TLR3 recognizes double-stranded (ds) RNA, generated by virus infected or apoptotic cells. TLR3 has been genetically linked to several human diseases, including some without viral etiology. Unlike other TLRs, TLR3 requires phosphorylation of two specific tyrosine residues, in its cytoplasmic domain, to initiate signaling. Here, we demonstrate that the two protein tyrosine kinases, the epidermal growth factor receptor ErbB1 and Src, bind sequentially to dsRNA-activated TLR3 and phosphorylate the two tyrosine residues, which is required for the recruitment of the adaptor protein, TRIF. Thus, these results reveal a connection between antiviral innate immunity and cell growth regulators.

INTRODUCTION

From Drosophila to human, innate immune defense against infectious agents and other harmful stresses is triggered by Toll or Toll-like receptors (TLR) (1, 2). Mammalian TLRs are trans-membrane proteins, which recognize specific microbial products to trigger cellular innate immune defense and shape adaptive immune responses against the respective infectious agents (2, 3). They also recognize other stress signals, such as cellular apoptosis, that may not be of microbial origin, thus broadening their roles in engaging the immune system to maintain homeostasis (4). The nucleic acid recognizing TLRs reside in endosomal membranes and among them TLR3 recognizes dsRNA (5, 6), which is produced by virus-infected cells as well as cells undergoing apoptosis. Consequently genetic evidence indicates the importance of TLR3 in not only viral diseases but human diseases of non-viral etiology as well (7–9). Although TLR3 can be present in different cellular membranes, it signals from the early endosomes (10), where endocytosed dsRNA binds to TLR3 within the lumen and causes dimerization and conformational changes in TLR3 (11, 12). TLR3 signaling, which leads to the induction of genes such as those encoding interferons, has unique characteristics not shared with other TLRs. Upon activation by dsRNA, the adaptor protein TRIF (Toll-interleukin-1 receptor domain-containing adapter protein inducing interferon beta), instead of MyD88 (Myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88) is recruited to TLR3 through the Toll/interleukin-1 receptor (TIR) domain (13). TRIF acts as a platform to recruit signaling molecules such as TRAF3 (TNF Receptor-Associated Factor 3), TBK1 (TANK-Binding Kinase 1), IKKε (Inhibitor of KappaB Kinase epsilon), TRAF2 (TNF receptor-associated factor 2), TRAF6 (TNF receptor-associated factor 6), to activate downstream transcription factors, IRF-3 (Interferon Regulatory Factor-3) and NF-κB (Nuclear Factor Kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells) (2, 5). Unlike other TLRs, phosphorylation of Tyr759 and Tyr858 in the cytoplasmic domain of TLR3 is required to activate downstream TLR3 signaling, which includes recruitment of TRIF and activation of IFR-3 and NF-κB (14–16). The protein tyrosine kinase that phosphorylates the Tyr residues in TLR3 remains to be identified. Although the tyrosine kinase Src binds to TLR3, it does not appear to be the kinase that phosphorylates these Tyr residues because apparently Src binding follows, rather than precedes, the recruitment of TRIF to TLR3 (10). Here, we report that the recruitment of another tyrosine kinase, the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), by dsRNA-bound TLR3 is an early event of the signaling process which is followed by Src recruitment, TLR3 Tyr phosphorylation, TRIF recruitment and the rest of the signaling process.

RESULTS

EGFR is essential for TLR3-signaling

To identify the specific protein tyrosine kinase responsible for phosphorylation of TLR3, we screened protein tyrosine kinase inhibitors using an antiviral assay against a green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV). When VSV replicates, virally encoded GFP is produced in high quantity; consequently the cells which support VSV replication appear green. Thus, the strength of the GFP signal is directly proportional to the efficiency of the virus replication. Treatment of cells with dsRNA activates TLR3 signaling, causing induction of antiviral genes and inhibition of VSV replication. Hence, inhibition of virus replication is a readout of the efficacy of the TLR3 signaling. AG1478, which inhibits the protein tyrosine kinase activity of EGFR, blocked the dsRNA-triggered inhibition of VSV replication in HT1080 cells (Fig. 1A). dsRNA treatment of MDA-MB-453 cells (17), which lack functional EGFR, did not inhibit VSV replication, an effect that was restored by ectopic expression of the ErbB1 isoform of EGFR (Fig. 1B). dsRNA treatment reduced virus yield by more than 99% as determined by plaque assays of VSV replication, an effect that was eliminated by the EGFR inhibitor (Fig 1C). dsRNA treatment of MDA-MB-453 cells did not induce P60 and P56, the products of two IRF-3 driven genes, unless EGFR was present (Fig. 1D). However, EGFR was not needed for gene induction in MDA-MB-453 cells by transfected dsRNA, a process that uses the cytoplasmic RIG-I-like helicases (18–20) (Fig. 1E). Under our experimental conditions of adding dsRNA to the culture medium, gene induction was mediated solely by TLR3 and not the cytoplasmic helicases because IPS-1, the adaptor for RIG-I-like helicases, was needed to respond to transfected dsRNA, but not added dsRNA (fig. S1A) and EGFR activity was needed for TLR3 stimulation by dsRNA (fig. S1A), but not for RIG-I stimulation by Sendai virus infection (fig. S1, B and C). The requirement for EGFR activity in TLR3 signaling was also necessary for dsRNA to trigger gene expression in primary bone marrow-derived dendritic cells and macrophages (fig. S1, D and E). The generality of the need for EGFR in TLR3 signaling was confirmed by ablating EGFR expression in two human cell lines, Wt11 (HEK293 cells expressing Flag-tagged wild-type TLR3) and HT1080 (Fig. 1, F and G). Expression profiling by microarray analysis confirmed that IRF-3 or NF-κB-dependent genes were induced by TLR3 activation in the absence of EGFR (Fig. 1H and table S1). A major dsRNA-induced gene encodes interferon (IFN) β, and the microarray profile showed that it was not induced in the absence of active EGFR (highlighted in table S1), a conclusion that was confirmed by RT-PCR for IFNB1 mRNA (Fig. 1I) and ELISA for secreted IFN (Fig. 1J). Treating cells with EGF to activate the protein tyrosine kinase activity of EGFR enhanced P56 gene induction by a limiting amount of dsRNA (Fig. 1K) indicating that the protein tyrosine kinase activity of EGFR correlated to TLR3 signaling. In the next series of experiments, we investigated the various stages of TLR3 signaling, to identify the specific target of EGFR. The block in signaling was at an early stage because TLR3 activation by dsRNA did not cause IRF-3 phosphorylation (21, 22) or its nuclear translocation in MDA-MB-453 cells, although TLR3 and its adaptor protein TRIF were present (Fig. 2, A and B). Indeed, TRIF recruitment to TLR3 in response to dsRNA treatment did not occur in MDA-MB-453 cells without ectopic EGFR expression (Fig. 2C).

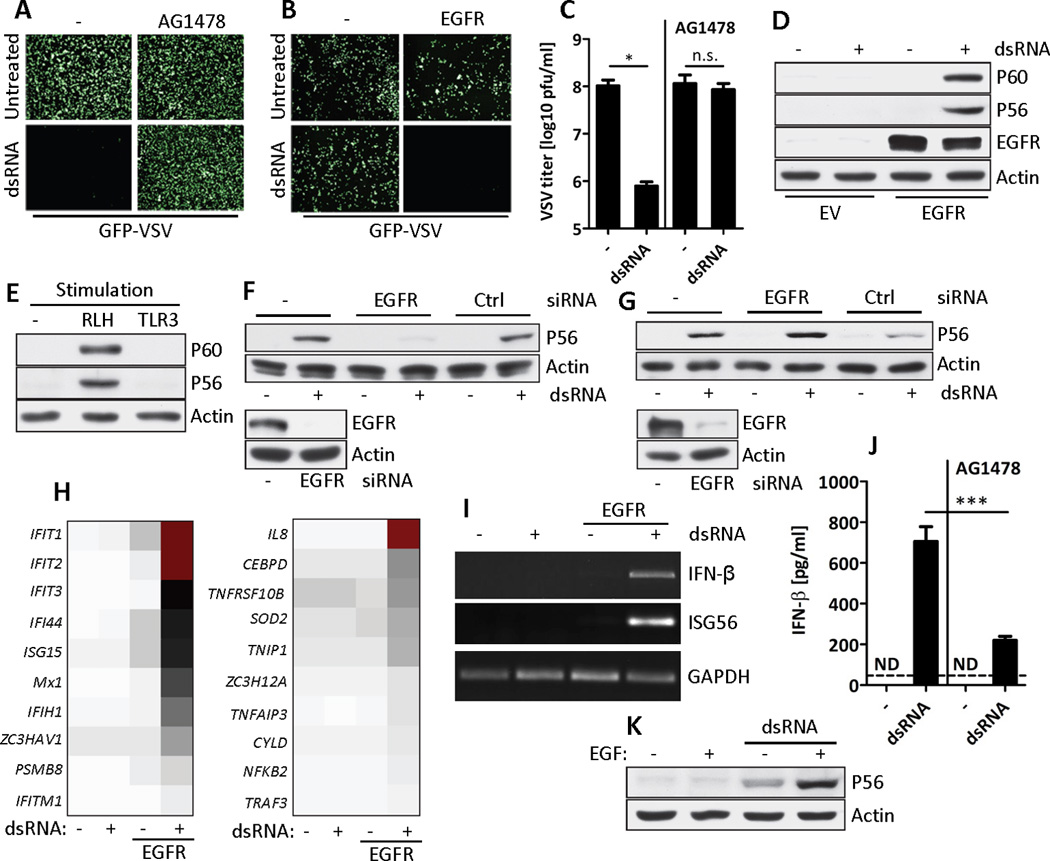

Fig. 1. EGFR is essential for TLR3 signaling.

(A and B) Antiviral effect of TLR3 signaling (dsRNA) was tested in GFP-VSV infected HT1080 cells in the presence of EGFR inhibitor (AG1478) (A) or EGFR-reconstituted MDA-MB-453 (EGFR) cells (B). (C) WT VSV titers were determined by plaque assay from VSV-infected HT1080 cells before and after TLR3 signaling (dsRNA) in the presence or the absence of AG1478, n=3, *, p=0.0124, n.s., not significant. (D) Western Blot analysis of the induction of P60 and P56 by TLR3 signaling (dsRNA) in EGFR-reconstituted MDA-MB-453 cells. (E) Western Blot analysis for the induction of P60 and P56 by TLR3 and RLH signaling in MDA-MB-453 cells. (F and G) Western Blot analysis for the induction of P56 by TLR3 signaling (dsRNA) in EGFR-knockdown Wt11 (F) or HT1080 (G) cells (upper panel). Cell lysates were immunoblotted for EGFR and actin (lower panel). (H) Microarray analysis of total RNA from parental or EGFR-reconstituted MDA-MB-453 cells after TLR3 signaling (dsRNA). Representative subsets of IRF-3 (left) and NF-κB-dependent (right) genes, in descending order of signal intensity (represented by the color), are shown. (I) RT-PCR for IFNB1, IFIT1 (which encodes P56) and GAPDH mRNAs from parental or EGFR-reconstituted MDA-MB-453 cells before and after TLR3 signaling (dsRNA). (J) Murine IFN-β concentrations were quantified in the supernatant of primary BMDMs before and after TLR3 signaling in the absence or the presence of AG1478, n=3,***, p=0.0004. ND, not detected. (K) EGF treatment enhances the induction of P56 by a limited amount of dsRNA in Wt11 cells. Data is a representative of at least two independent experiments.

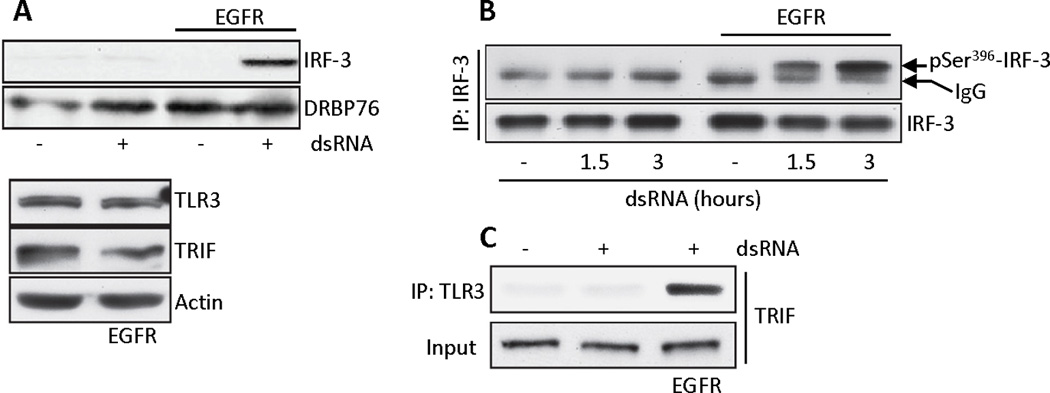

Fig. 2. EGFR is required for activation of IRF-3 and recruitment of TRIF by TLR3.

(A) Parental or EGFR-reconstituted MDA-MB-453 cells were treated with dsRNA, nuclear fractions were isolated and immunoblotted for IRF-3 and DRBP76 (a nuclear marker) (upper panel). Cell lysates were immunoblotted for TLR3, TRIF and actin (lower panel). (B) Parental or EGFR-reconstituted MDA-MB-453 cells were treated with dsRNA for the indicated times, cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-IRF-3 and the immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted for phospho-Ser396-IRF-3. (C) Co-immunoprecipitation of TRIF with TLR3 in EGFR-reconstituted MDA-MB-453 cells expressing Flag-TLR3. Cell lysates were immunoblotted for TRIF (input). Blots shown are representative of three independent experiments.

EGFR interacts with TLR3

We examined whether TLR3 interacts with EGFR. Because TLR3 signals from the early endosomal membrane (10) and endosomal membranes are rich in EGFR (23, 24), this possibility was reasonable. Indeed, under our assay conditions of culturing cells in the presence of serum, substantial amounts of EGFR were present in the early endosomes of cells before dsRNA-treatment, as evidenced by the co-localization of EGFR and EEA1, a marker for the early endosomes (Fig. 3A). Leucine-rich repeat kinase 1 (LRRK1) is required for the transit of EGFR from the early endosomes to the late endosome (25) and the absence of this protein (fig. S2A, lower panel) did not affect gene induction by TLR3 (fig. S2A, upper panel) because it did not affect the localization of EGFR in the early endosomes of HT1080 cells (fig. S2B). Co-immunoprecipitation experiments demonstrated that endogenous ErbB1 (an EGFR isoform) bound to both ectopically expressed TLR3 in Wt11 cells (Fig. 3B, left panel) and endogenous TLR3 in HT1080 cells (Fig. 3B, right panel). The binding was dependent on ligand-activation of TLR3 and transient. For the ErbB1-TLR3 interaction, the Tyr residues of TLR3 were not needed (Fig. 3C) indicating that the interaction of EGFR with TLR3 did not occur through recognition of its phosphotyrosine residues. Similarly, TRIF was not required for EGFR binding to TLR3 (Fig. 3D). Another isoform of EGFR, ErbB2 (26), also bound to TLR3 (Fig. 3E); however its ablation by siRNA did not affect gene induction by TLR3 signaling (Fig. 3F).

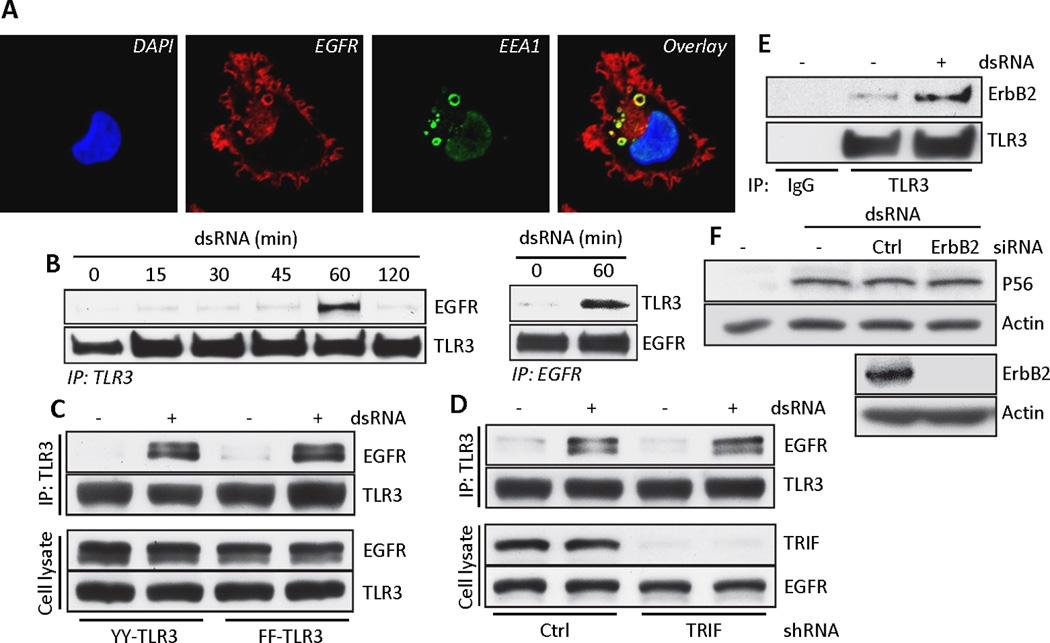

Fig. 3. EGFR interaction with TLR3 is independent of TLR3 tyrosine residues and TRIF.

(A) Confocal microscopy of HT1080 cells, immuno-labeled for endogenous EGFR (red) and EEA1 (green), an early endosomal marker. Yellow rings in the overlay show their co-localization. (B) Co-immunoprecipitation of EGFR with ectopic TLR3 from dsRNA-stimulated Wt11 cells (left panel) and co-immunoprecipitation of endogenous TLR3 with EGFR from dsRNA-stimulated HT1080 cells (right panel). (C) Co-immunoprecipitation of EGFR with TLR3 in HEK293 cells expressing the YY (Tyr759, Tyr858, FFYFY) or FF (FFFFF) mutants of TLR3. Cell lysates were immunoblotted for EGFR and TLR3. (D) Co-immunoprecipitation of EGFR with TLR3 in Wt11 cells transfected with TRIF shRNA. Cell lysates were immunoblotted for TRIF and EGFR. (E) Co-immunoprecipitation of ErbB2 with TLR3 from Wt11 cells upon TLR3 signaling. (F) Western Blot analysis for the induction of P56 by dsRNA in Wt11 cells transfected with ErbB2 siRNA. Data presented are representative of at least three independent experiments.

Src binding to TLR3 is EGFR-dependent

The protein tyrosine kinase Src is activated upon binding to TLR3 after dsRNA-activation (10). We investigated the requirement for Src-binding to TLR3. Src bound to endogenous TLR3 only after dsRNA-stimulation (Fig. 4A). This interaction did not require the kinase activity of Src (Fig. 4B), its SH2 domain (Fig. 4C) or the Tyr residues of TLR3 (Fig. 4D), thus ruling out phosphorylated Tyr-SH2 domain association as the basis for the interaction. The TLR3-specific adaptor protein TRIF has been suggested to mediate the interaction between TLR3 and Src (10). However, our results revealed that TRIF was not required for the Src-TLR3 interaction either in mouse cells (Fig. 4E) or in human cells (fig. S3A); it was also not required for Src activation (Fig. 4F). Similarly, the adaptor protein TRAF3 (27), which is recruited to the TLR3-TRIF complex and needed for signaling, was not required for phosphorylation of Src (Fig. 4G). In contrast to previous suggestions (10), these data indicate that the Src-TLR3 interaction was not mediated by the adaptor proteins that bind to TLR3. Our observations with EGFR (Figs. 1 to 3) prompted us to examine whether Src and EGFR binding to TLR3 were interdependent. Indeed, EGFR was required for Src-binding to TLR3 both in mouse cells (Fig. 4H and fig. S3B) and human cells (Fig 4I). In contrast, Src was not required for EGFR binding to TLR3 (Fig. 4, J and K and fig. S3C). These results demonstrated that after dsRNA-stimulation, TLR3 binds EGFR before Src does.

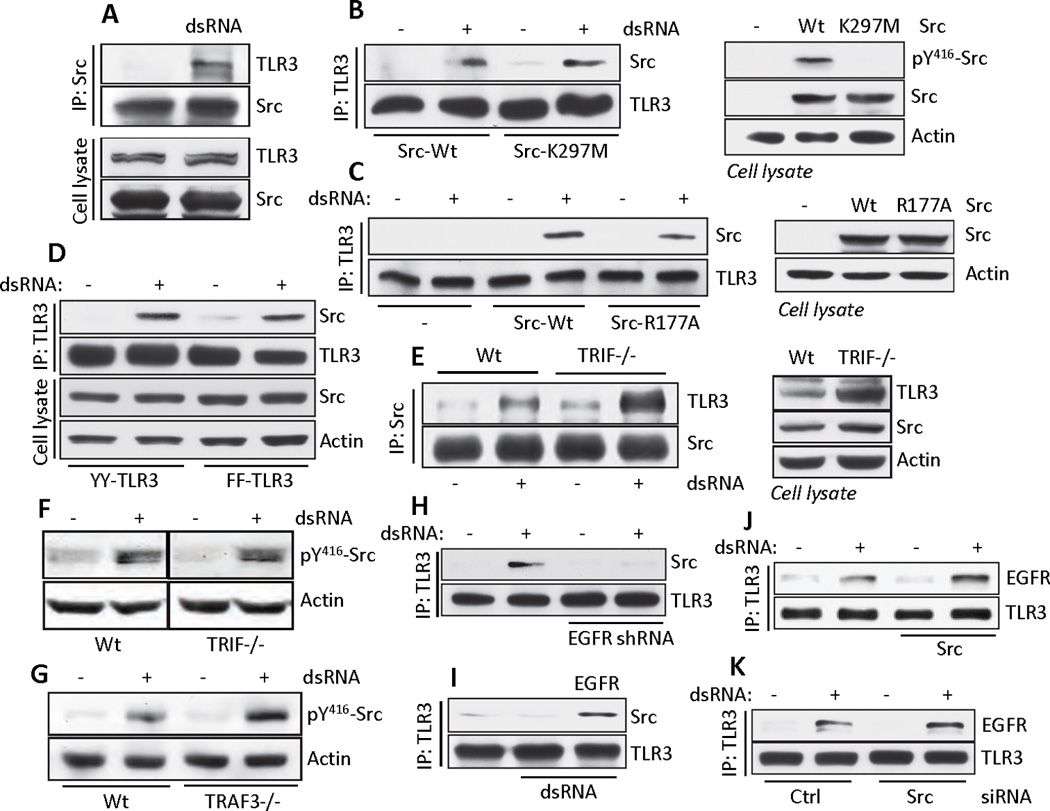

Fig. 4. Src interaction with TLR3 is independent of TRIF and TRAF3, but dependent on EGFR.

(A) Co-immunoprecipitation of endogenous TLR3 with Src in HT1080 cells upon TLR3 signaling. Cell lysates were immunoblotted for TLR3 and Src. (B and C) Co-immunoprecipitation of Src with TLR3 from TLR3-expressing SYF−/− MEFs reconstituted with wild-type or kinase dead mutant (K297M) Src (B) or wild-type or SH2 domain inactive mutant (R177A) Src (C) (left panels). Cell lysates were immunoblotted for phospho-Src, total Src and actin (right panels). (D) Co-immunoprecipitation of Src with TLR3 in HEK293 cells expressing the YY or FF TLR3 mutants. Cell lysates were immunoblotted for Src and actin. (E) Co-immunoprecipitation of TLR3 with Src in WT or Ticam1−/− MEFs upon TLR3 signaling (dsRNA, left panel). Cell lysates were immunoblotted for TLR3, Src and actin (right panel). (F) Western Blot analysis of phospho-Src in WT or TRIF−/− MEFs upon TLR3 signaling (dsRNA). (G) Western Blot analysis of phospho-Src in WT or TRAF3−/− MEFs after activation of TLR3 signaling (dsRNA). (H and I) Co-immunoprecipitation of Src with TLR3 in TLR3−/− MEFs expressing EGFR shRNA and Flag-TLR3 (H) or parental or EGFR-reconstituted MDA-MB-453 cells (I). (J and K) Co-immunoprecipitation of EGFR with TLR3 in SYF−/− MEFs reconstituted with Src (J) or in Wt11 cells transfected with Src siRNA (K). Data presented are representative of at least three independent experiments.

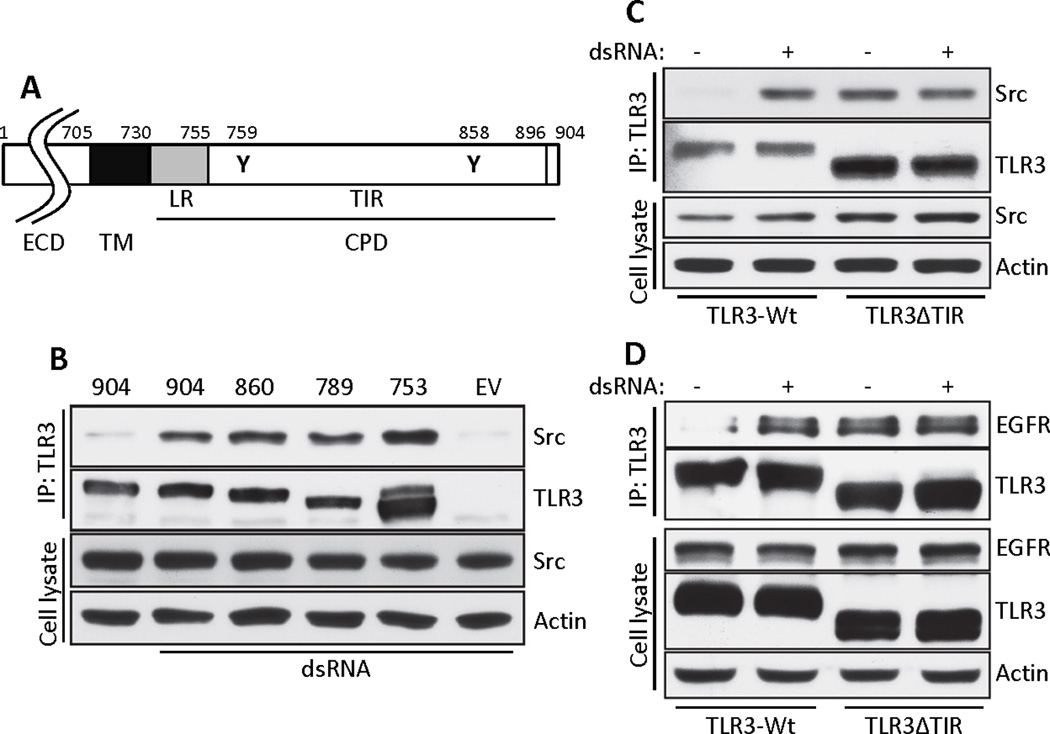

To map the region of TLR3 that is required for the recruitment of the protein tyrosine kinases, we expressed in HEK293 cells (which lack endogenous TLR3) a nested set of deletion mutants of TLR3 which contained decreasing lengths of the cytoplasmic domain of TLR3 (Fig. 5A). All of the mutants bound Src, including ΔTIR, which contains only the linker region of the cytoplasmic domain of TLR3 (1-753aa) (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, this mutant bound Src constitutively, unlike wild-type TLR3 which bound Src in a ligand-dependent manner (Fig. 5C). EGFR-binding to TLR3 had also the same characteristics as Src-binding, namely that the linker region of TLR3 was sufficient and binding was ligand-independent in the absence of the TIR domain (Fig. 5D). Taken together, these results suggest that in unstimulated cells, the TIR domain of TLR3 prevents EGFR binding to the linker region and the conformational change of TLR3 (11) that follows dsRNA binding makes the linker region accessible for interaction with EGFR and consequently Src.

Fig. 5. The TIR domain of TLR3 is not required for its interaction with Src and EGFR.

(A) Schematic representation of human TLR3. LR: linker region, ECD: ectodomain, TM: transmembrane domain, CPD: cytoplasmic domain. The locations of the two critical Tyr residues are noted by residue numbers. (B) The TLR3-Src interaction was tested by co-immunoprecipitation from HEK293 cells expressing progressive C-terminal deletion mutants of YY-TLR3. The C-terminal residue numbers are shown on the top. Cell lysates were immunoblotted for Src and actin. (C) Co-immunoprecipitation of Src with TLR3 in HEK293 cells expressing WT or the ΔTIR mutant of TLR3. Cell lysates were immunoblotted for Src and actin. (D) Co-immunoprecipitation of EGFR with TLR3 in HEK293 cells expressing WT or the ΔTIR mutant of TLR3. Cell lysates were immunoblotted for EGFR, TLR3 and actin. Data presented are representative of at least three independent experiments.

Src and EGFR are required for phosphorylation of Tyr759 and Tyr858 in TLR3

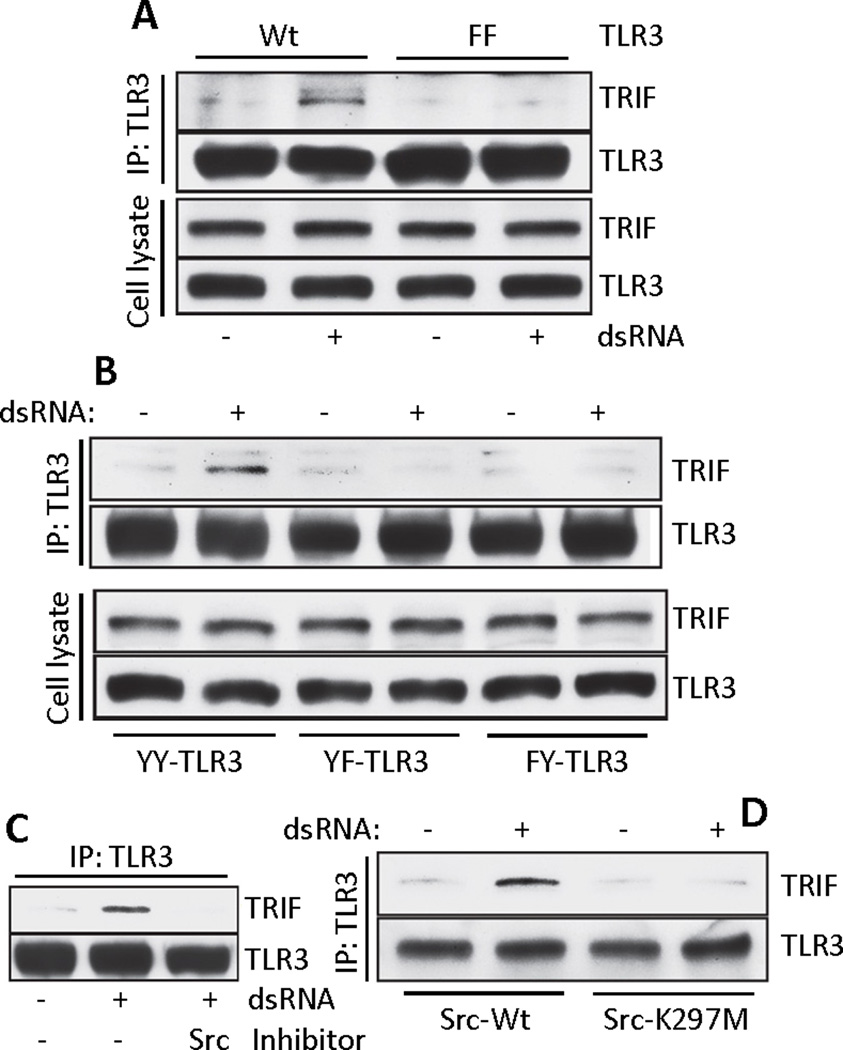

We assessed the effect of phosphorylation of TLR3 on TRIF recruitment to TLR3. TRIF was not recruited to a form of TLR3 in which all five Tyr residues in the cytoplasmic domain of TLR3 had been mutated (the FF mutant) (Fig. 6A). We have shown before that, two tyrosine residues of TLR3 cytoplasmic domain (Tyr759 and Tyr858) are sufficient for downstream signaling ((15, 16)). Consistent with this conclusion, a signal-competent mutant (YY-TLR3), in which Tyr759 and Tyr858 remained but the other three Tyr residues had been mutated to Phe, could recruit TRIF (Fig. 6B). Individual contribution of the two tyrosine residues was further investigated by mutating them in the context of YY-TLR3. Our results indicate that the presence of both Tyr residues was needed for TRIF recruitment because forms of TLR3 with Phe substitutions of all Tyr residues except Tyr759 (YF-TLR3) or all Tyr residues except Tyr858 (FY-TLR3) did not bind to TRIF (Fig. 6B). TRIF recruitment was also dependent on the kinase activity of Src. TRIF was not recruited in cells treated with a chemical inhibitor of Src (Fig. 6C) or expressing a kinase-dead mutant of Src (28) (Fig. 6D). These results suggested that Src and EGFR phosphorylated the two Tyr residues of TLR3 which are required for TRIF recruitment and subsequent signaling.

Fig. 6. Tyrosine phosphorylation of TLR3 is required for recruitment of TRIF.

(A) Co-immunoprecipitation of TRIF with TLR3 in WT- or FF-TLR3 expressing HEK293 cells. Cell lysates were immunoblotted for TRIF and TLR3. (B) Co-immunoprecipitation of TRIF with TLR3 from HEK293 cells expressing YY, YF or FY mutants of TLR3. Cell lysates were immunoblotted for TRIF and TLR3. (C) Co-immunoprecipitation of TRIF with TLR3 in Wt11 cells in the absence or the presence of the Src inhibitor PP2. (D) Co-immunoprecipitation of TRIF with TLR3 from Flag-TLR3 expressing SYF−/− MEFs reconstituted with WT Src or the kinase dead mutant (K297M). Blots shown here are representative of at least three independent experiments.

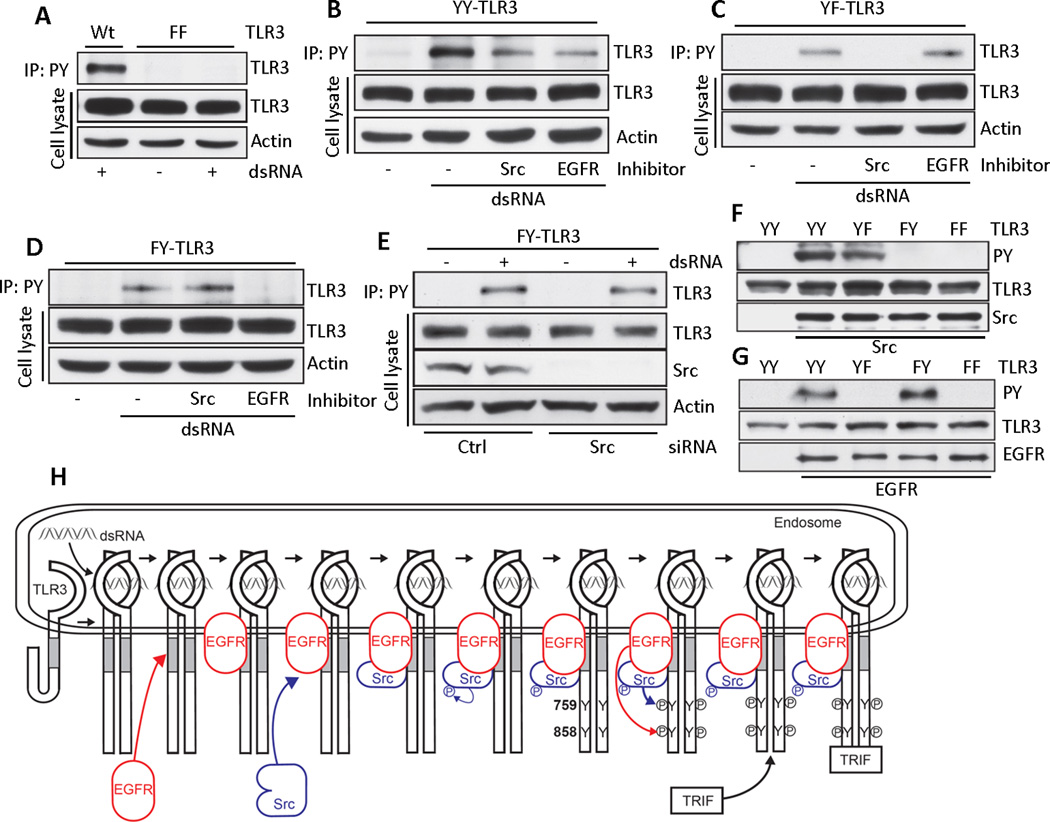

To analyze Tyr phosphorylation of TLR3, immunoprecipitations were done under conditions that ensured disruption of TLR3 interaction with other phosphotyrosine containing proteins, such as Src (Fig. 7A). Both Src and EGFR inhibitors partially blocked Tyr phosphorylation of wild-type TLR3 (fig. S4A) or YY-TLR3 (Fig. 7B). Similar results were obtained in cells expressing kinase-dead Src (fig. S4B). The requirement of both EGFR and Src raised the possibility that each targets different essential Tyr residues of TLR3. To test this idea, we used the YF and FY mutants of TLR3. Src kinase activity was required for Tyr759 phosphorylation (Fig. 7C and fig. S4C), whereas EGFR kinase activity was required for Tyr858 phosphorylation (Fig. 7D and fig. S4D), which occurred in the absence of Src (Fig. 7E).

Fig. 7. Src and EGFR are required for phosphorylation of Tyr759 and Tyr858 in TLR3.

(A) WT- or FF-TLR3 expressing HEK293 cells were treated with dsRNA. Anti-phosphotyrosine antibody (PY) immunoprecipitates from these cells were immunoblotted for TLR3. Cell lysates were immunoblotted for TLR3 (Flag) and actin. (B-D) YY, YF or FY-TLR3 expressing HEK293 cells were treated with dsRNA in the absence or the presence of inhibitors of Src (PP2) or EGFR (AG1478). Anti-P-Tyr (PY) immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted for TLR3. Cell lysates were immunoblotted for TLR3 and actin. (E) Anti-P-Tyr (PY) immunoprecipitates from FY-TLR3 expressing, Src knockdown HEK293 cells were immunoblotted for TLR3. Cell lysates were immunoblotted for TLR, Src and actin. (F and G) In vitro kinase reactions were performed using recombinant active Src (F) or active EGFR (G) and recombinant cytoplasmic domains of mutants of TLR3. Reaction mixtures were analyzed by Western Blot. (H) A model depicting the early steps of TLR3 signaling. Data presented are representative of at least two independent experiments.

EGFR and Src directly phosphorylate the essential Tyr residues of TLR3

Protein kinases often function by phosphorylating cascades of proteins. We used an in vitro phosphorylation assay to determine whether the two Tyr residues of TLR3 were direct targets of the two Tyr kinases. The cytoplasmic domains of wild-type and mutant TLR3 were expressed as polyhistidine tagged proteins in bacteria and purified. They were tested, in vitro, as substrates of active EGFR and Src individually, and Tyr phosphorylation was detected by immunoblotting for phosphotyrosine. YY-TLR3 and YF-TLR3 (which has a Phe substitution at Tyr858), but not FY-TLR3 (which has a Phe substitution at Tyr759) or FF-TLR3 (which has Phe substitutions at Tyr759 and Tyr858), were phosphorylated by Src (Fig. 7F). In contrast, EGFR phosphorylated YY-TLR3 and FY-TLR3, but not YF-TLR3 or FF-TLR3 (Fig. 7G). From the above results, it is reasonable to conclude that EGFR directly phosphorylates Tyr858 and Src directly phosphorylates Tyr759 and phosphorylation of both residues is needed for TRIF recruitment to TLR3.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we established that EGFR is essential for TLR3 signaling. This requirement was observed in all cell types that we tested, including several human and mouse lines and primary mouse fibroblasts, dendritic cells and macrophages. EGFR was not required for the dsRNA-recognizing RIG-I-like cytoplasmic receptors, which mechanistically do not need protein tyrosine kinases to signal. Nucleic acid-recognizing TLRs signal from membranes of internal organelles; for example, TLR3 signals from early endosomal membranes (10). dsRNA is endocytosed from the culture medium and when it reaches the lumen of early endosomes, it binds to TLR3 to start the signaling process. We found that these membranes also contain EGFR, even in cells not exposed to dsRNA (Fig. 3A). Because we routinely culture our cells and perform all experiments in the presence of 10% fetal bovine serum, it is possible that the presence of EGFR in internal membranes was stimulated by the presence of EGF in the culture medium; indeed, exogenously added EGF enhanced TLR3 signaling (Fig. 1K). Our results also indicated that the late endosomes, which can also contain EGFR and TLR3, are not the signaling platform because when we ablated the expression of LRRK1, a protein required for the transit of EGFR from the early to the late endosome (25), TLR3 signaling was unaffected (fig. S2). Our results provide a clearer picture of the early events of TLR3 signaling (Fig. 7H). dsRNA binding to TLR3 in the early endosomal lumen leads to its dimerization and conformational changes (11, 12) that expose the linker region of its cytoplasmic domain from masking by the TIR. EGFR docks to the linker region domain and brings in Src; the two protein tyrosine kinases phosphorylate Tyr858 and Tyr759 respectively, which is followed by TRIF recruitment, assembly of the signaling complex, activation of the transcription factors, gene induction and antiviral effects. These findings revealed several new features of TLR signaling from the endosomal membrane to the cytoplasm. The involvement of protein tyrosine kinases in TLR signaling is unique to TLR3; these protein tyrosine kinases are abundant in endosomal membranes (29) because EGFR is a transmembrane protein and Src is attached to the membrane by its myristoylation modification. The requirement of phospho-Tyr in TLR3 for TRIF recruitment to the receptor has not been reported for other TLRs and because TRIF does not have any recognizable SH2 domain, the biochemical basis of TLR3-recognition by TRIF remains to be determined. We have previously reported that phosphoinositide-3 kinase (PI3K) binds to TLR3 and is required for the full activation of IRF-3 and NF-κB (15, 16). In the light of the results reported here, it will be important to investigate in the future whether PI3K binds directly to TLR3 or to EGFR or Src, recruited by TLR3. Finally, our observations revealed unexpected connections between innate immunity and protein tyrosine kinases that regulate both normal and abnormal cell growth. Such connections may have unanticipated implications; for example, one would predict that cross regulation of the activities of TLR3, Src and EGFR would alter viral innate immune responses of cancer patients being treated with antagonists of EGFR or Src (30).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and Reagents

HEK293 cells, MDA-MB-453 cells (ATCC, Vanassas, VA, USA), HT1080 cells, Traf3-/− MEFs (Xiaoxia Li, Lerner Research Institute, Cleveland Clinic, OH), SYF−/− MEFs [which are deficient in Src, Yes and Fyn (ATCC, Vanassas, VA, USA)], Ticam1−/− MEFs (Katherine Fitzgerald, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA, USA), Mavs−/− MEFs (Robert Silverman, Cleveland Clinic, OH),wild-type or mutant Src-restored SYF−/− MEFs, Tlr3−/−− MEFs, their corresponding wild-type MEFs, were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS (Atlanta Biologicals, Lawrenceville, GA, USA), 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin (complete media). HEK293 cells expressing Flag-tagged wild-type TLR3 (Wt11) were described elsewhere (15). HEK293 cells lentivirally expressing wild-type or mutants of TLR3 were maintained in 1 µg/ml puromycin-containing complete media. Anti-Flag M2 antibody, anti-Flag M2 affinity gel, anti-actin antibody, and human recombinant EGF were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). Antibodies against Src, phospho-Tyr416-Src and LRRK1 were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA) and Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA), respectively; anti-human TLR3 (ab13915) and anti-mouse TLR3 (ab53424) were from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA); anti-human TRIF (4596), anti-EGFR, anti-ErbB2, and anti-phospho-Ser396 IRF-3 were from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA, USA); anti-mouse TRIF (LS-C749/22434) were from LifeSpanBioSciences (Seattle, WA, USA); antibodies against IRF-3, His, and GST were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology; anti-phosphotyrosine (4G10 platinum) was from Millipore (Billerica, MA, USA); antibodies against P54, P56, P60, and DRBP76 were raised in our laboratory. Poly(I:C) (dsRNA) was purchased from GE Healthcare (Piscataway, NJ, USA). GFP-VSV virus was kindly provided by Curt Horvath (Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, USA). A cDNA encoding mouse Src gene was obtained from George Stark (Lerner Research Institute, Cleveland Clinic, OH, USA). EGFR cDNA was purchased from Millipore. AG1478 (used at 50 µM) and PP2 (used at 1 µM) were from EMD Biosciences (San Diego, CA, USA).

TLR3, Src, and EGFR plasmids

Flag-tagged wild-type human TLR3 cDNA construct has been described previously (15). The TLR3 cytoplasmic domain tyrosine mutants, YY-TLR3 (FFYFY), YF-TLR3 (FFYFF), FY-TLR3 (FFFFY), and FF-TLR3 (FFFFF) were generated by the mega-primer PCR method using Flag-tagged wild-type TLR3 cDNA as the template. The deletion mutants of YY-TLR3 containing amino acid 1-860, 1-789, or 1-753 (ΔTIR) were generated by PCR-based method using Flag-YY TLR3 as the template. All mutations were confirmed by sequencing, and subcloned into pLVX-IRES-puro vector (Clontech, Mountain view, CA, USA) for lentiviral expression. Mouse Src in lentiviral vector, pLVX-IRES-Puro (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA) was used as a template to generate kinase-dead (K297M) Src (28, 31), inactive SH2 domain (R177A) Src (32) by the mega-primer PCR method. All mutations were confirmed by sequencing. Cells were lentivirally transduced with wild-type or mutant Src. EGFR mutant (K721R) was generated by the mega-primer PCR method using pUSEamp EGFR (wild-type) plasmid as template; the mutation was confirmed by sequencing. MDA-MB-453 cells were transfected with wild-type or K721R (kinase dead) EGFR plasmid by the calcium phosphate method.

Antiviral assay and virus titration

Cells were either left untreated or treated with poly(I:C) for 16 hours, the cells were washed with PBS and infected with VSV expressing GFP (GFP-VSV) or wild-type VSV (Indiana) at MOI of 10. For virus infection, the cells were incubated with the virus in infection medium (DMEM supplemented with 2% serum) for 1 hour with occasional agitation. The virus was removed, and cells were washed with DMEM (twice) and the cells were placed in complete media until they were harvested. To quantify the infectious virus particles, wild-type VSV-infected HT1080 cells were frozen and thawed 8 hours post infection, and viral titers were determined by plaque assay on Vero cells.

RNAi-mediated knockdown

ShRNA plasmids pLKO.1-puro targeting human EGFR (TRCN0000010329, TRCN0000121067, and TRCN0000121202), pLKO.1-puro targeting mouse EGFR (TRCN0000055218, TRCN0000055219, TRCN0000055220, TRCN0000055221, and TRCN0000055222), pLKO.1-puro targeting human TRIF (TRCN0000123199, TRCN0000123200, TRCN0000123201, and TRCN0000123203), and non-targeting control shRNA plasmid (SHC002) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA), and the mixture of lentivirus media was used. Target cells were transduced lentivirally in the presence of polybrene (8 µg/ml) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Sixteen hours post infection, the media were removed, and cells were allowed to recover in complete growth media for 36–48 hours before using the selection media containing puromycin (1 µg/ml). EGFR and TRIF knockdown were confirmed by Western Blot. For Src knockdown, ON-TARGET plus SMART pool SRC and non-targeting control pool were purchased from Thermo Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). The siRNA pool was transfected using DharmaFECT 1 following the manufacturer’s instructions. After 72 hours of transfection, co-immunoprecipitation experiments were performed. Src knockdown was confirmed by Western Blot. For LRRK1 knockdown, HT1080 cells were transfected with ON-TARGET plus SMART pool siRNA (Thermo Scientific) using DharmaFECT 4; 48 hours later, cells were used for experiments.

Western Blot and immunoprecipitation

Western Blotting was performed as described elsewhere (15). For immunoprecipitations, cells were lysed in buffer containing 20 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 150 mMNaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM DTT, 2 mM EGTA, 10 mM NaF, 12.5 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM Na3VO4, 0.5% (v/v) Triton X-100 and protease inhibitors (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Cell lysates were precleared with mouse IgG agarose (Sigma, St. Louse, MO, USA) for 1 hour, and precleared lysates were incubated overnight with anti-Flag M2 beads (Sigma). After incubation, beads were washed, boiled with SDS-PAGE buffer, analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blot. Nuclear fractions were prepared as described previously (15).

Tyr phosphorylation of TLR3

Cell lysates were precleared with mouse IgG agarose for 1 hour. The precleared lysates were incubated with anti-phosphotyrosine Ab (Platinum 4G10, Millipore) for 1 hour, followed by incubation with Protein A/G PLUS Agarose (Santa Cruz) overnight. After incubation, beads were washed with cell lysis buffer containing 500 mM NaCl, 1% SDS, and 1% Triton X-100, boiled with SDS-PAGE buffer and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western Blot. Tyr phosphorylated TLR3 was detected by Western Blot with anti-Flag Ab.

In vitro kinase assay

Recombinant proteins containing the TLR3 cytoplasmic domain (CPD) (amino acids 726 to 904) with or without Tyr substitution with Phe, were generated using full length YY-TLR3 as a template and cloned into pHIS-parallel2 vector (33). TLR3 CPD plasmids were transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) and protein expression was induced by 1mM isopropyl β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) for 8 hours at 30°C. His-tagged TLR3 proteins were purified using Ni-NTA superflow beads (Qiagen) as described previously (34) and used for in vitro phosphorylation reactions using active Src or EGFR (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) in reaction buffer (20 mM MOPS/NaOH pH7.0, 1 mM EDTA) with 0.1 mM cold ATP at 30°C for 10 min. Tyrosine phosphorylation of TLR3 was detected by Western Blot with phosphotyrosine antibody (4G10 Platinum®, Millipore).

Microarray analysis and RT-PCR

For quantitative profiling of mRNA abundance by microarray, parental or EGFR-reconstituted 453 cells were stimulated with 100 µg/ml poly(I:C) for 6 hours, RNA extraction was carried out by TRIzol (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After RNA extraction, samples were treated with recombinant DNase I (Ambion) for 1 hour. The enzyme was inactivated and the RNA was further purified by using the RNAeasy kit (Qiagen). RNA was then analyzed in an Illumina Human Ref-8 gene array and the data analysis was carried out by using Illumina Genome Studio V2009.2. For RT-PCR, reverse transcription (RT) of the RNA was performed with the Superscript III kit (Invitrogen); PCRs were driven by Hot Start Taq polymerase (Denville). The RT-PCR primers used were as follows: IFN-β: 5′-ACCAACAAGTGTCTCCTCCA, and 3′-GAGGTAACCTGTAAGTCTGT; ISG56: 5′- TCTCAGAGGAGCCTGGCTAAG, and 3′- GTCACCAGACTCCTCACATTTGC; GAPDH: 5′- AAAATCAAGTGGGGCGATGCT, and 3′- GGGCAGAGATGATGACCCTTT.

IFN-β ELISA

Primary mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) were stimulated with dsRNA in the absence or the presence of EGFR inhibitor (AG1478) for 16 hours. IFN-β was quantified in supernatants by ELISA (PBL).

Confocal microscop

Cells were grown on glass coverslips; after fixation and permeabilization with 4% paraformaldehyde and 0.2% Triton X-100, 20 min each, objects were blocked with 5% normal goat serum and labeled with anti-EGFR (C74B9, Cell Signaling) and goat-anti-rabbit-AlexaFluor-647 (Invitrogen). Endosomes were stained with FITC-conjugated anti-EEA1 (BD Transduction Labs). Objects were mounted on glass slides in VectaShield/DAPI, images were taken by confocal laser scanning microscopy (Leica TCS-SP/DM RXE-7) and overlaid using Leica LCS software.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance of differences between two groups was tested by two-tailed t-test using Prism 5 software (GraphPad).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Katherine Fitzgerald, George Stark, Rakesh Kumar, Xiaoxia Li, Robert Silverman, Phil Howe for important reagents and Ying Zhang for technical assistance. Funding: This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant PO1 CA062220.

Footnotes

Author contributions: M.Y., S.C., V.F., P.S., and G.C.S. conceived and designed the experiments, M.Y., S.C., V.F., P.S., and J.L.W. performed the experiments, M.Y., S.C., V.F., P.S., and G.C.S. analyzed data and interpreted results, M.Y., and G.C.S. wrote the manuscript. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Janeway CA, Jr., Medzhitov R. Innate immune recognition. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:197–216. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.083001.084359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kawai T, Akira S. Toll-like receptors and their crosstalk with other innate receptors in infection and immunity. Immunity. 2011;34:637–650. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Severa M, Fitzgerald KA. TLR-mediated activation of type I IFN during antiviral immune responses: fighting the battle to win the war. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2007;316:167–192. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-71329-6_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cavassani KA, Ishii M, Wen H, Schaller MA, Lincoln PM, Lukacs NW, Hogaboam CM, Kunkel SL. TLR3 is an endogenous sensor of tissue necrosis during acute inflammatory events. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2609–2621. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vercammen E, Staal J, Beyaert R. Sensing of viral infection and activation of innate immunity by toll-like receptor 3. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2008;21:13–25. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00022-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iwakiri D, Zhou L, Samanta M, Matsumoto M, Ebihara T, Seya T, Imai S, Fujieda M, Kawa K, Takada K. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-encoded small RNA is released from EBV-infected cells and activates signaling from Toll-like receptor 3. J Exp Med. 2009;206:2091–2099. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kleinman ME, Yamada K, Takeda A, Chandrasekaran V, Nozaki M, Baffi JZ, Albuquerque RJ, Yamasaki S, Itaya M, Pan Y, Appukuttan B, Gibbs D, Yang Z, Kariko K, Ambati BK, Wilgus TA, DiPietro LA, Sakurai E, Zhang K, Smith JR, Taylor EW, Ambati J. Sequence- and target-independent angiogenesis suppression by siRNA via TLR3. Nature. 2008;452:591–597. doi: 10.1038/nature06765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cole JE, Navin TJ, Cross AJ, Goddard ME, Alexopoulou L, Mitra AT, Davies AH, Flavell RA, Feldmann M, Monaco C. Unexpected protective role for Toll-like receptor 3 in the arterial wall. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:2372–2377. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018515108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang Z, Stratton C, Francis PJ, Kleinman ME, Tan PL, Gibbs D, Tong Z, Chen H, Constantine R, Yang X, Chen Y, Zeng J, Davey L, Ma X, Hau VS, Wang C, Harmon J, Buehler J, Pearson E, Patel S, Kaminoh Y, Watkins S, Luo L, Zabriskie NA, Bernstein PS, Cho W, Schwager A, Hinton DR, Klein ML, Hamon SC, Simmons E, Yu B, Campochiaro B, Sunness JS, Campochiaro P, Jorde L, Parmigiani G, Zack DJ, Katsanis N, Ambati J, Zhang K. Toll-like receptor and geographic atrophy in age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:145–1463. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnsen IB, Nguyen TT, Ringdal M, Tryggestad AM, Bakke O, Lien E, Espevik T, Anthonsen MW. Toll-like receptor 3 associates with c-Src tyrosine kinase on endosomes to initiate antiviral signaling. Embo J. 2006;25:3335–3346. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leonard JN, Ghirlando R, Askins J, Bell JK, Margulies DH, Davies DR, Segal DM. The TLR3 signaling complex forms by cooperative receptor dimerization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:258–263. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710779105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Bouteiller O, Merck E, Hasan UA, Hubac S, Benguigui B, Trinchieri G, Bates EE, Caux C. Recognition of double-stranded RNA by human toll-like receptor 3 and downstream receptor signaling requires multimerization and an acidic pH. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:38133–38145. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507163200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamamoto M, Sato S, Hemmi H, Hoshino K, Kaisho T, Sanjo H, Takeuchi O, Sugiyama M, Okabe M, Takeda K, Akira S. Role of adaptor TRIF in the MyD88-independent toll-like receptor signaling pathway. Science. 2003;301:640–643. doi: 10.1126/science.1087262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sarkar SN, Smith HL, Rowe TM, Sen GC. Double-stranded RNA signaling by Toll-like receptor 3 requires specific tyrosine residues in its cytoplasmic domain. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:4393–4396. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200655200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sarkar SN, Peters KL, Elco CP, Sakamoto S, Pal S, Sen GC. Novel roles of TLR3 tyrosine phosphorylation and PI3 kinase in double-stranded RNA signaling. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:1060–1067. doi: 10.1038/nsmb847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sarkar SN, Elco CP, Peters KL, Chattopadhyay S, Sen GC. Two tyrosine residues of Toll-like receptor 3 trigger different steps of NF-kappa B activation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:3423–3427. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600226200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lupu R, Colomer R, Zugmaier G, Sarup J, Shepard M, Slamon D, Lippman ME. Direct interaction of a ligand for the erbB2 oncogene product with the EGF receptor and p185erbB2. Science. 1990;249:1552–1555. doi: 10.1126/science.2218496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoneyama M, Fujita T. Structural mechanism of RNA recognition by the RIG-I-like receptors. Immunity. 2008;29:178–181. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loo YM, Gale M., Jr. Immune signaling by RIG-I-like receptors. Immunity. 2011;34:680–692. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakhaei P, Genin P, Civas A, Hiscott J. RIG-I-like receptors: sensing and responding to RNA virus infection. Semin Immunol. 2009;21:215–222. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Servant MJ, Grandvaux N, tenOever BR, Duguay D, Lin R, Hiscott J. Identification of the minimal phosphoacceptor site required for in vivo activation of interferon regulatory factor 3 in response to virus and double-stranded RNA. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:9441–9447. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209851200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mori M, Yoneyama M, Ito T, Takahashi K, Inagaki F, Fujita T. Identification of Ser-386 of interferon regulatory factor 3 as critical target for inducible phosphorylation that determines activation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:9698–9702. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310616200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sorkin A, Goh LK. Endocytosis and intracellular trafficking of ErbBs. Exp Cell Res. 2008;314:3093–3106. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.07.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stahl PD, Barbieri MA. Multivesicular bodies and multivesicular endosomes: the "ins and outs" of endosomal traffic. Sci STKE. 2002;2002:pe32. doi: 10.1126/stke.2002.141.pe32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hanafusa H, Ishikawa K, Kedashiro S, Saigo T, Iemura S, Natsume T, Komada M, Shibuya H, Nara A, Matsumoto K. Leucine-rich repeat kinase LRRK1 regulates endosomal trafficking of the EGF receptor. Nature communications. 2011;2:158. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coussens L, Yang-Feng TL, Liao YC, Chen E, Gray A, McGrath J, Seeburg PH, Libermann TA, Schlessinger J, Francke U, et al. Tyrosine kinase receptor with extensive homology to EGF receptor shares chromosomal location with neu oncogene. Science. 1985;230:1132–1139. doi: 10.1126/science.2999974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hacker H, Redecke V, Blagoev B, Kratchmarova I, Hsu LC, Wang GG, Kamps MP, Raz E, Wagner H, Hacker G, Mann M, Karin M. Specificity in Toll-like receptor signalling through distinct effector functions of TRAF3 and TRAF6. Nature. 2006;439:204–207. doi: 10.1038/nature04369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kamps MP, Taylor SS, Sefton BM. Direct evidence that oncogenic tyrosine kinases and cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase have homologous ATP-binding sites. Nature. 1984;310:589–592. doi: 10.1038/310589a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murphy JE, Padilla BE, Hasdemir B, Cottrell GS, Bunnett NW. Endosomes: a legitimate platform for the signaling train. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:17615–17622. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906541106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Woodburn JR. The epidermal growth factor receptor and its inhibition in cancer therapy. Pharmacol Ther. 1999;82:241–250. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(98)00045-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kamps MP, Sefton BM. Neither arginine nor histidine can carry out the function of lysine-295 in the ATP-binding site of p60src. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6:751–757. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.3.751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Waksman G, Shoelson SE, Pant N, Cowburn D, Kuriyan J. Binding of a high affinity phosphotyrosyl peptide to the Src SH2 domain: crystal structures of the complexed and peptide-free forms. Cell. 1993;72:779–790. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90405-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sheffield P, Garrard S, Derewenda Z. Overcoming expression and purification problems of RhoGDI using a family of "parallel" expression vectors. Protein expression and purification. 1999;15:34–39. doi: 10.1006/prep.1998.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Terenzi F, Saikia P, Sen GC. Interferon-inducible protein, P56, inhibits HPV DNA replication by binding to the viral protein E1. Embo J. 2008;27:3311–3321. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.