Abstract

Wilms tumors (WT) have provided broad insights into the interface between development and tumorigenesis. Further understanding is confounded by their genetic, histologic, and clinical heterogeneity, the basis of which remains largely unknown. We evaluated 224 WT for global gene expression patterns; WT1, CTNNB1, and WTX mutation; and 11p15 copy number and methylation patterns. Five subsets were identified showing distinct differences in their pathologic and clinical features: these findings were validated in 100 additional WT. The gene expression pattern of each subset was compared with published gene expression profiles during normal renal development. A novel subset of epithelial WT in infants lacked WT1, CTNNB1, and WTX mutations and nephrogenic rests and displayed a gene expression pattern of the postinduction nephron, and none recurred. Three subsets were characterized by a low expression of WT1 and intralobar nephrogenic rests. These differed in their frequency of WT1 and CTNNB1 mutations, in their age, in their relapse rate, and in their expression similarities with the intermediate mesoderm versus the metanephric mesenchyme. The largest subset was characterized by biallelic methylation of the imprint control region 1, a gene expression profile of the metanephric mesenchyme, and both interlunar and perilobar nephrogenic rests. These data provide a biologic explanation for the clinical and pathologic heterogeneity seen within WT and enable the future development of subset-specific therapeutic strategies. Further, these data support a revision of the current model of WT ontogeny, which allows for an interplay between the type of initiating event and the developmental stage in which it occurs.

Introduction

The initiation and progression of the most common adult cancers result from a stepwise accumulation of multiple genetic events within a finite number of pathways occurring over many years. In contrast, the initiation of neoplasia in children results from one to two genetic events that occur over the course of months rather than years. These events usually involve genes responsible for normal development and result in tumors that closely resemble cells within the developing embryo. They are also often the same genetic events that participate in the development of adult tumors. Therefore, pediatric embryonal neoplasms provide invaluable insights into normal development and into both adult and childhood neoplasia. The investigation of Wilms tumor (WT), one of the most common tumors of childhood, is a remarkable illustration of this. This unique success is due in part to the fact that WT is the only embryonal neoplasm that arises within precursor lesions known as nephrogenic rests, of which there are two predominant types: perilobar and intralobar [1]. WTs are also capable of showing a striking spectrum of appearances ranging from undifferentiated “blastemal” tumors to “teratoid” tumors composed of a mixture of differentiated skeletal muscle, chondroid, and a variety of epithelial cell types. This heterogeneity implies a complexity to the underlying causes of WT that has fascinated investigators for decades.

Two genetic loci have consistently been associated with the pathogenesis of WT, the WT1 gene at 11p13, and the WT2 locus at 11p15. WT1 encodes a transcription factor important in multiple phases of normal renal, gonadal, and cardiac development [2,3]. Germline mutations of WT1 result in syndromes, including Denys-Drash and Wilms tumor-aniridia-genitourinary malformation-mental retardation: both are characterized by an increased risk of WT and abnormal genitourinary development [4–6]. Somatic mutations of WT1 are seen in 10% to 20% of sporadic WT [7–9]. Frequently accompanying WT1 mutation is canonical Wnt activation, most commonly due to activating mutation of β-catenin (CTNNB1) [10,11]. Inactivating mutations of WTX, a protein that contributes to β-catenin degradation, may also occur in 15% to 20% of patients with WT, regardless of their WT1 mutation status [12–15]. While canonical Wnt- activating mutations likely occur subsequent to WT1 mutation [16,17], whether or not Wnt activation is required for tumor development after WT1 mutation is not clear. Nor is the role of Wnt activation in WT that lack WT1 mutation known.

The WT2 chromosomal region came to scientific attention with the observations of 11p15 loss of heterozygosity (LOH) or loss of imprinting (LOI) in a large proportion of sporadic WT [18], and 11p15 uniparental disomy (UPD) or duplication in patients with Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome (BWS), which carries an increased risk of WT and developmental abnormalities including organ and limb overgrowth [19–22]. 11p15 methylation abnormalities resulting in WT are accompanied by aberrant methylation at imprint control region 1 (ICR1), resulting in biallelic expression of IGF2, a gene normally expressed only from the paternally inherited allele [21,23]. Although 11p15 clearly plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of WT, the observation of 11p15 LOH in normal tissue from some WT patients [24] and the lack of tumors arising in mutant mice with ICR1 LOI [25] imply that biallelic expression of IGF2 alone is insufficient for tumor development.

Other loci implicated in WT infrequently are the familial predisposition loci FWT1 at 17q12–q21 and FWT2 at 19q13.4 [26,27]. The documented association between relapse and LOH for 1p and 16q [28] is being used to stratify patients within the current Children's Oncology Group therapeutic protocols. The critical genes within these regions are not known.

In summary, despite the wealth of knowledge that the investigation of WT has provided, much remains unknown and further progress is made difficult by the genetic, histologic, and clinical heterogeneity that characterizes WT. The goal of this study was to investigate patterns of global gene expression and known genetic and epigenetic changes in a large number of prospectively identified WTs to identify and characterize distinctive subsets that may merit therapeutic stratification or respond to specific therapies. In addition, the recent availability of large data sets of gene expression patterns identified in microdissected samples of different embryologic stages and in different cell types during normal renal development [29,30] offers a unique opportunity to place each of these WT subsets within their developmental context. We have accomplished this, and here we provide a revised ontogenic model for the development of WT.

Materials and Methods

Clinical Samples

Samples were taken from a case-cohort sampling previously described [31]. Briefly, all patients with Favorable Histology Wilms Tumor (FHWT) registered on the National Wilms Tumor Study 5 for whom pretreatment tumor tissues were available were identified. From the resulting 1451 patients, all those known to have relapsed and a random sample including approximately 30% of the remaining were identified. The resulting 600 patients were randomly divided into two groups of 300 patients each. The use of case-cohort sampling allows for the resource-efficient investigation of clinical outcome in a tumor characterized by a low relapse rate. Institutional review board approval and informed consent were obtained for all tumor specimens. Frozen sections of each sample confirmed more than 80% viable cellular tumor. Pathologic features (diagnosis, local stage, histologic pattern, skeletal muscle quantification, presence, and type of nephrogenic rests) were recorded prospectively at the time of central pathology review. Skeletal muscle quantification represents the estimated proportion of the tumor volume containing cells with cross striations.

Gene Expression Analysis

Samples were hybridized to Affymetrix U133A arrays, scanned, subjected to quality control standards, and normalized as previously described [32]. Gene expression patterns were identified through unsupervised analysis using average linkage clustering with CLUSTER and displayed with TreeView (http://rana.lbl.gov/EisenSoftware.htm) [33]. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis v.2.5 (GSEA) was used to identify those gene lists that best define the different tumor subsets. GSEA ranks the expression of each gene based on its correlation with one of two phenotypes being compared. It then determines the presence and ranking of each gene within available independent gene lists queried. From this ranking, it calculates an enrichment score that reflects the degree to which genes in the independent gene list are overrepresented. The normalized enrichment score (NES) takes into account the number of genes within the independent gene set. Leading-edge genes are those that account for the gene set's enrichment signal.

Loss of Heterozygosity for 1p, 16q

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) microsatellite analysis was performed prospectively during National Wilms Tumor Study 5 as previously described in detail [28].

Methylation Analysis at 11p15 ICR1 and ICR2

Methylation of the paternally methylated ICR1 (controlling H19 and IGF2 expression) and the maternally methylated ICR2 (KvDMR1, whose methylation is independent of ICR1) was determined using specific restriction sites recognized by methylation-sensitive enzymes as previously described [34]. Retention of imprinting (ROI) was defined as 30% to 70% methylation of both ICR1 and ICR2, LOI was defined as 80% to 100% methylation of ICR1 and 30% to 70% methylation of ICR2, and LOH was defined as 80% to 100% methylation of ICR1 and 0% to 20% methylation of ICR2. Tumors with values outside these ranges were not classified.

11p15 Copy Number Analysis

Samples with 11p15 LOH were analyzed for 11p15 copy number using multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) to assess for UPD (two identical copies of 11p15) using four probe sets to loci on 11p15, as previously described [34].

Mutation Analysis for WT1, CTNNB1, and WTX

Tumor DNAs were assessed for WT1 point mutations by analysis of PCR products from all 10 exons and for partial or complete deletion of WT1 by quantitative real-time PCR analysis using amplicons for the promoter/exon 1, exon 2/3, exon 4, exon 5, exon 6, exon 7, exon 8/9, and exon 10 of WT1, as previously described [14,34,35]. Tumor DNAs were analyzed for point mutations in CTNNB1 (exons 3, 7, and 8), as previously described [10,14]. To detect WTX mutations, the entire coding region was amplified as a single PCR product and sequenced. Quantitative PCR was performed to detect deletions, as previously described [14].

Results

Identification of Subsets of WT by Gene Expression Patterns

We first analyzed the global gene expression pattern of the 224 samples from the first group of 300 patients that passed quality control parameters. Unsupervised hierarchical clustering using the top 2000, 4000, and 10,000 most variable genes demonstrated two subsets (S1 and S2) that were stable in each analysis, identifying the same samples within each subset (Figure 1A, blue and red bars). S1 and S2 tumors were then removed, the most highly variable genes were reidentified from the remaining tumors, and hierarchical clustering was again performed. This did not reveal new subsets with consistent expression patterns.

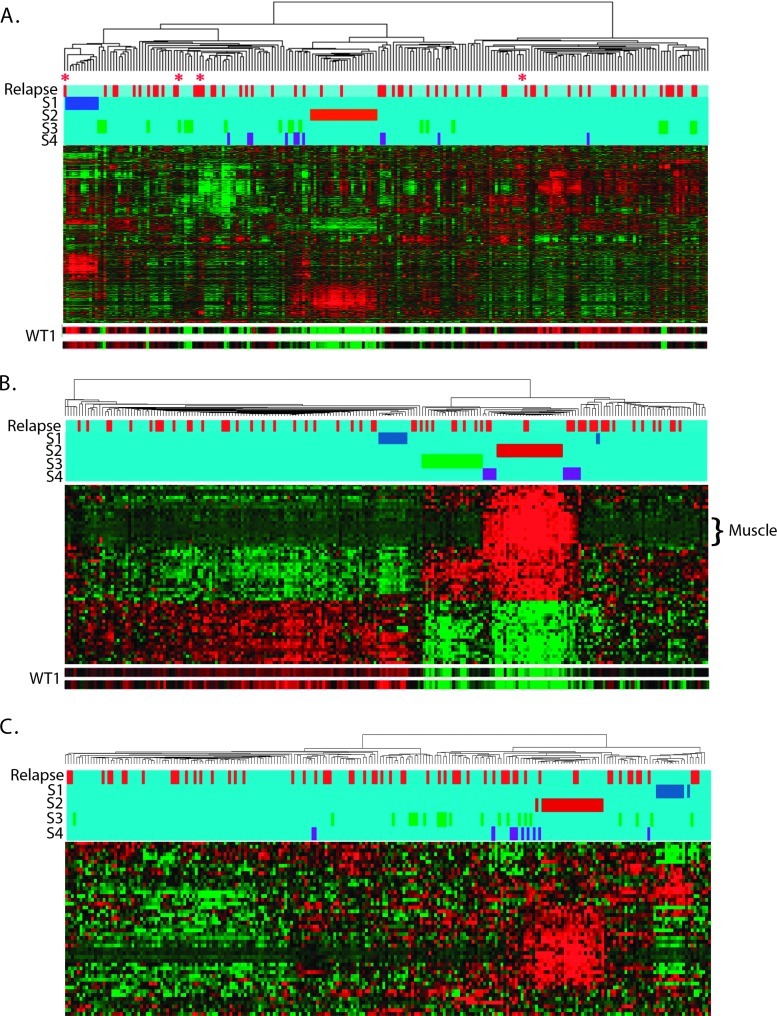

Figure 1.

Hierarchical analysis of 224 FHWT: (A) Unsupervised hierarchical analysis using the 4000 probe sets with the highest coefficient of variation. Two subsets are designated by the blue (S1) and red bars (S2). Also shown are the tumors identified in B in green (S3) and purple (S4). Tumors that relapsed are designated in red at the top of the dendrogram. Expression of genes, clustered on the y axis, is shown with levels ranging from high (red) to low (green). The expressions of the two WT1 probe sets are illustrated separately at the bottom. Four tumors outside S1 that show solely epithelial tubular differentiation are marked with a red asterisk. See Table W1 for the top 100 genes differentially expressed in S1 to S4 compared with S5. (B) Hierarchical analysis using the 54 genes with a Pearson correlation coefficient greater than 0.60 or less than -0.60 for both available WT1 alleles. S1 and S2 are readily identified (blue and red bars). Two additional subsets are now apparent, indicated by green (S3) and purple bars (S4). Genes associated with muscle differentiation are marked. (C) Hierarchical analysis of Wnt targets with a coefficient of variation greater than 0.06. S1 (blue) and S2 (red) clustered tightly together. Tumors in S3 (green) and S4 (purple) did not show evidence of strong Wnt activation and did not cluster.

A key gene differentially expressed in S2 tumors is WT1 (Figure 1A). To better assess the role of WT1 in the overall expression pattern, 54 unique genes were identified due to their Pearson Correlation Coefficient (PCC) scores of less than -0.6 or greater than 0.6 for both available WT1 probe sets compared with all probe sets on the array. Hierarchical analysis using these 54 genes again identifies S1 and S2 (Figure 1B, blue and red bars), as well as an additional subset, S3 (green bar in Figure 1B). Lastly, two small groups of tumors flank the S2 tumors and are grouped together as S4 (Figure 1B, purple bars). There is no evidence of clustering of the S3 and S4 tumors within the original unsupervised analysis (Figure 1A). Tumors outside of S1 to S4 (the majority of tumors) are classified as S5. The top 100 genes differentially expressed in each of S1, S2, S3, and S4 compared with S5 as determined by GSEA are provided in Table W1. The gene expression data are deposited in National Center for Biotechnology Information's Gene Expression Omnibus, accessible at GEO Series accession no. GSE31403 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE31403).

Clinical and Pathologic Features of FHWT Subsets

The features of WT within S1 to S4 are listed in Table 1, and these results are compared with the remaining S5 tumors in Table 2 and are summarized below:

Subset 1 tumors (n = 11) occur in infants and all have a distinctive epithelial tubular differentiated histologic pattern throughout. All lack both nephrogenic rests and skeletal muscle differentiation, and none relapsed.

Subset 2 tumors (n = 23) present at an early median age, have a mixed (triphasic) histology and commonly arise within intralobar nephrogenic rests (ILNRs). Of 22 evaluable S2 tumors, 9, 12, and 1 display muscle differentiation comprising 5% or less, 10% to 25%, and 80% of the tumor volume, respectively. Two relapses occurred, and two additional patients developed contralateral tumors after therapy.

Subset 3 tumors (n = 21) are pathologically similar to S2, with less skeletal muscle differentiation. Of 21 evaluable tumors, 13, 4, and 4 showed absent, 5% or less, and 10% to 25% skeletal muscle, respectively. Seven relapses occurred.

Subset 4 tumors (n = 11) are also pathologically similar to S2: skeletal muscle differentiation was identified in 6 of 10 evaluable S4 tumors, with 3, 2, and 1 showing 5% or less, 10%, and 40% skeletal muscle, respectively. Six patients relapsed.

Subset 5 tumors (n = 158): 70 triphasic (mixed), 76 blastemal predominant, 9 epithelial predominant, and 3 stromal predominant. Skeletal muscle is present in 27 (17%) of 156 evaluable tumors (24/27 with <5%, 2 with 5%–15%). Of 154 evaluable tumors, 38 (25%) contain perilobar nephrogenic rests (PLNR) and 5 of 38 also contain ILNRs. ILNRs alone are identified in 23 (15%) of 154 tumors. Five of the 224 patients in this study had bilateral WT at diagnosis, and all belong to S5. Fifty S5 patients relapsed. It should be noted that while the relapse rates in these five subsets show clear differences, they do not achieve statistical significance; the small sample size may contribute to this.

Table 1.

Features of Tumors in Subsets.

| Relapse | Stage | Histology (Weight) | Age (months) | Rests | 11p15 Status | 1p LOH | 16q LOH | Mutations | |||

| WT | CTNNB1 | WTX | |||||||||

| Subset 1 | |||||||||||

| WT00-082 | No | I | Epithelial (390 g) | 8 | None | ROI | NO | NO | No | No | No |

| WT00-269 | No | I | Epithelial (789 g) | 10 | None | ROI | NO | NO | No | No | No |

| WT00-177 | No | I | Epithelial (333 g) | 13 | None | ROI | NO | NO | No | No | No |

| WT00-175 | No | I | Epithelial (580 g) | 14 | None | ROI | NO | NO | No | No | No |

| WT00-054 | No | I | Epithelial (207 g) | 17 | None | ROI | NO | NO | No | No | No |

| WT00-002 | No | I | Epithelial (31 g) | 18 | None | ROI | NA | NA | No | No | No |

| WT00-173 | No | I | Epithelial (86 g) | 39 | None | ROI | NO | NO | No | No | No |

| WT00-167 | No | II | Epithelial (393 g) | 91 | None | LOI | NO | NO | No | No | No |

| WT00-153 | No | I | Epithelial (485 g) | 15 | None | ROI | NO | NO | No | No | No |

| WT00-086 | No | I | Epithelial (230 g) | 6 | None | ROI | NO | NO | No | No | No |

| WT00-185 | No | I | Epithelial (315 g) | 7 | NE | ROI | NO | NO | No | No | No |

| Subset 2 | |||||||||||

| WT00-196 | No | I | Mixed | 3 | ILNR | ROI | NO | NO | No | No | No |

| WT00-270 | No | I | Mixed | 14 | ILNR | LOH | NO | NO | No | No | No |

| WT00-171 | No | II | Mixed | 43 | None | LOH | LOH | NO | No | No | No |

| WT00-237 | No | III | Mixed | 11 | ILNR | LOH | NO | NO | No | No | Yes (XX) |

| WT00-216 | No | II | Mixed | 20 | ILNR | ROI | NO | NO | No | Exon 8 | No |

| WT00-264 | No | I | Mixed | 41 | None | LOI | NO | NO | No | Exon 8 | No |

| WT00-166 | No | I | Mixed | 37 | None | LOH | NO | NO | No | Exon 8 | Yes (XX) |

| WT00-128 | No | I | Mixed | 57 | ILNR | LOH | NO | NO | No | Exon 7 | Yes (XY) |

| WT00-074 | No | II | Mixed | 7 | ILNR | LOH | NA | NA | No | Exon 3 | No |

| WT00-290 | Yes | II | Mixed | 27 | ILNR | ROI | NO | NO | No | Exon 3 | No |

| WT00-027 | No | III | Stromal | 5 | ILNR | LOH | NO | NO | Yes | Exon 3 | No |

| WT00-232 | No | I | Mixed | 12 | ILNR | ROI | NO | NO | Yes | Exon 3 | No |

| WT00-152 | No | II | Mixed | 70 | ILNR | ROI | NO | NO | Yes | Exon 3 | No |

| WT00-254 | No | III | Mixed | 35 | None | ROI | NO | NO | Yes | Exon 3 | No |

| WT00-288 | No | II | Mixed | 8 | ILNR | LOH | NO | NO | Yes | Exon 3 | Yes* (XY) |

| WT00-156 | No | II | Mixed | 9 | ILNR | LOH | NO | NO | Yes | Exon 3 | No |

| WT00-061 | Yes | II | Stromal | 9 | ILNR | LOH | NO | NO | Yes | Exon 3 | No |

| WT00-072 | No | II | Mixed | 13 | ILNR | LOH | ND | ND | Yes | Exon 3 | No |

| WT00-113 | No | III | Stromal | 9 | ILNR | LOH | NO | NO | Yes | Exon 3 | No |

| WT00-244 | No | III | Mixed | 12 | ILNR | ROI | NO | NO | Yes | Exon 3 | No |

| WT00-064 | No | III | Mixed | 13 | None | LOH | NO | NO | Yes | Exon 8 | Yes (XY) |

| WT00-193 | No | II | Mixed | 111 | ILNR | LOH | ND | ND | Yes | Exon 7 | Yes (XY) |

| WT00-112 | No | III | Blastemal | 39 | None | ND | NO | LOH | ND | ND | ND |

| Subset 3 | |||||||||||

| WT00-110 | No | II | Mixed | 57 | None | LOI | NO | NO | No | No | No |

| WT00-285 | No | III | Mixed | 57 | ILNR | LOH | NO | NO | No | No | No |

| WT00-142 | No | III | Mixed | 55 | None | ROI | NO | NO | No | No | No |

| WT00-127 | No | I | Mixed | 17 | ILNR | LOI | NO | NO | No | No | No |

| WT00-135 | Yes | II | Mixed | 5 | ILNR | ROI | NO | NO | No | No | No |

| WT00-220 | No | II | Mixed | 36 | ILNR | LOH | LOH | LOH | No | No | No |

| WT00-277 | Yes | III | Mixed | 120 | NA | ROI | NO | NO | No | No | No |

| WT00-209 | No | III | Mixed | 35 | None | ROI | NO | NO | No | No | Yes (p.XX) |

| WT00-098 | No | II | Mixed | 41 | ILNR | LOI | NO | NO | No | No | Yes (p.XX) |

| WT00-291 | Yes | III | Mixed | 28 | ILNR | ROI | NO | NO | No | Exon 3 | No |

| WT00-205 | No | I | Mixed | 44 | ILNR | ROI | NO | NO | Yes | Exon 3 | Yes (p,XY) |

| WT00-214 | No | II | Mixed | 0.2 | ILNR | ROI | NO | NO | Yes | Exon 3 | No |

| WT00-038 | No | I | Mixed | 21 | ILNR | ROI | NO | NO | Yes | Exon 3 | No |

| WT00-145 | Yes | III | Mixed | 10 | ILNR | ROI | NO | NO | Yes | Exon 3 | No† |

| WT00-106 | Yes | I | Mixed | 10 | ILNR | LOH | NO | NO | Yes | Exon 3 | No |

| WT00-023 | No | I | Mixed | 11 | ILNR | LOH | LOH | LOH | Yes | Exon 3 | No |

| WT00-297 | No | II/IV | Mixed | 39 | ILNR | LOH | NO | NO | Yes | Exon 8 | No |

| WT00-192 | No | III | Blastemal | 36 | ILNR | ROI | NO | NO | Yes | No | Yes (XY) |

| WT00-121 | Yes | III/IV | Blastemal | 87 | ILNR | LOH | NO | NO | Yes | No | No† |

| WT00-052 | Yes | II | Blastemal | 53 | ILNR | LOI | NO | NO | Yes | No | Yes (XX) |

| WT00-122 | No | III | Mixed | 58 | None | LOH | NO | NO | Yes(p) | No | No |

| Subset 4 | |||||||||||

| WT00-026 | Yes | I | Mixed | 8 | ILNR | LOH | NO | NO | Yes | No | No |

| WT00-204 | Yes | IV | Mixed | 73 | None | ROI | NO | NO | No | Exon 8 | Yes (XX) |

| WT00-076 | No | III | Mixed | 72 | None | LOI | NO | NO | No | No | Yes (XY) |

| WT00-172 | No | II | Mixed | 38 | None | LOH | NO | NO | No | No | No |

| WT00-206 | Yes | III | Mixed | 65 | ILNR | LOH | NO | LOH | No | Exon 8 | No† |

| WT00-276 | No | I | Mixed | 20 | ILNR | LOH | NO | NO | No | Exon 3 | No |

| WT00-018 | No | II | Mixed | 56 | Incon | LOH | ND | ND | No | Exon 3 | No |

| WT00-021 | No | II | Mixed | 17 | None | LOI | NO | NI | No | Exon 8 | No |

| WT00-050 | Yes | I | Mixed | 15 | None | ROI | NO | NO | No | No | No |

| WT00-190 | Yes | II | Mixed | 73 | None | ND | NO | NO | ND | ND | ND |

| WT00-168 | Yes | IV | Blastemal | 37 | NE | LOI | NO | LOH | No | No | No |

ND indicates not done; NE, not evaluable; NI, not informative; p, partial.

Missense mutation, unknown significance.

Missense mutation, known single nucleotide polymorphism.

Table 2.

Summary of Features in Subsets.

| No. Patient (%*) | Nephrogenic Rests (%) | Pathologic Features | Clinical Features | ICR1, ICR2 Methylation (%) | 1p LOH (%) | 16q LOH (%) | Mutation (%) | ||||||||

| ILNR | PLNR | Predominant Histology | Skeletal Muscle (%) | Median Age (months) | No. Relapse (%*) | 11p15 LOH | 11p15 LOI | 11p15 ROI | WT1 | CTNNB1 Exon 3 | WTX | ||||

| S1 | 11 (6.2%*) | 0 | 0 | Epithelial | 0 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 91 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S2 | 23 (12.1%)* | 74 | 0 | Mixed | 87 | 13 | 2 (3%*) | 63.5 | 4.5 | 32 | 5 | 5 | 54 | 55 | 22 |

| S3 | 21 (9.4%*) | 76 | 0 | Mixed | 38 | 39 | 7 (11%*) | 33.3 | 19.1 | 47.6 | 9.5 | 9.5 | 52 | 33 | 24 |

| S4 | 11 (3.8%*) | 30 | 0 | Mixed | 60 | 38 | 6 (16%*) | 50.0 | 30.0 | 20.0 | 0.0 | 22.0 | 10 | 20 | 10 |

| S5 | 158 (68.5%*) | 15 | 25 | Variable | 17 | 43.5 | 50 (13%*) | 37.2 | 43.8 | 19.0 | 14.3 | 26.8 | ND | ND | ND |

| Validation subsets | |||||||||||||||

| SA | 5 | 0 | 0 | Epithelial | 0 | 10 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 80 | 0 | 0 | |||

| SB | 7 | 86 | 0 | Mixed | 100 | 28 | 1 | 86 | 0 | 14 | 0 | 0 | |||

| SC | 8 | 38 | 0 | Mixed | 40 | 23 | 5 | 57.1 | 28.6 | 14.3 | 0 | 16.7 | |||

| SD | 80 | 19 | 16 | Variable | 15 | 42 | 25 | 51 | 31 | 12 | 20 | 25 | |||

Percentage adjusted for case-cohort design.

Characterizing Subsets of FHWT Based on Gene Expression

GSEA was used to characterize the gene expression patterns in the different subsets using the gene lists provided in Table 3. S1 to S4 tumors were individually compared with S5 tumors; S3 and S4 tumors were also compared with S2 tumors. Those gene lists with a false discovery rate (FDR) of 20% or less and nominal P ≤ .05 are provided in Table W2. These are grouped into categories according to their common leading edge genes, and these categories are provided in Table 4. The results of the above analyses are summarized below, beginning with the largest group, S5. The expression patterns of illustrative genes (designated with an asterisk [*] in the text) are shown in Figure 2.

Table 3.

Gene Lists Analyzed by Gene Set Enrichment Analysis.

| Gene Lists | Reference |

| All lists in GSEA v 2.5 from Gene Ontology Biologic Processes with >50 genes (C5): 225 lists | www.broadinstitute.org/gsea |

| All lists in GSEA v 2.5 from curated canonical pathways with >50 genes (C2): 88 lists | www.broadinstitute.org/gsea |

| List comparing WT to fetal kidney (LI) | [36] |

| Lists comparing WT with and without WT1 mutation (TYCKO) | [42] |

| Lists comparing WT with and without CTNNB1 mutation (ZIRN) | [66] |

| STANFORD Wnt signaling | www.stanford.edu/~rnusse/wntwindow.html |

| 15 lists characterizing different stages and cell types within the developing kidney (Brunskill A-0) | [29] |

| List characterizing the intermediate mesoderm (LIN) | [30] |

Table 4.

GSEA of S1 to S4 Compared with S5.

| Subset 1 | Median NES: S1 vs S5 | Median NOM P: S1 vs S5 | Median FDR: S1 vs S5 | ||||

| (A) GO biologic processes | |||||||

| Mitosis/cell cycle | -1.65 | .03 | 0.07 | ||||

| DNA replication | -1.56 | -05 | 0.08 | ||||

| Metabolic processes | 1.67 | .004 | 0.08 | ||||

| (B) Curated and published lists | |||||||

| LI_FETAL_VS_WT_KIDNEY_DN | -1.64 | .02 | 0.02 | ||||

| LI_FETAL_VS_WT_KIDNEY_UP | 1.55 | .03 | 0.08 | ||||

| NOTCH_SIGNALING_PATHWAY | 1.78 | <.001 | <0.01 | ||||

| (C) Renal developmental lists | |||||||

| Brunskill A: Early MM | -1.41 | .03 | 0.17 | ||||

| Brunskill D: Renal vesical, S body | 1.56 | .03 | 0.09 | ||||

| Brunskill L: Epithelial differentiation | 1.5 | .05 | 0.07 |

| S2, S3, S4 | Median NES: S2 vs S5 | Median NOM P: S2 vs S5 | Median FDR: S2 vs S5 | Median NES: S3 vs S5 | Median NES: S4 vs S5 | Median NES: S3 vs S2 | Median NES: S4 vs S2 |

| (A) GO biologic processes | |||||||

| Muscle development | 1.75 | <.001 | 0.01 | NS | 1.62 | -1.74 | NS |

| Morphogenesis and development | 1.71 | <.008 | 0.02 | NS | 1.71 | .1.67 | NS |

| Regulation of catalytic activity | 1.61 | <.001 | 0.05 | NS | 1.43 | -1.54 | NS |

| Regulation of transferase/kinase | 1.46 | .001 | 0.02 | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Cell cycle | 1.49 | .012 | 0.12 | NS | NS | .1.47 | NS |

| Signal transduction | 1.77 | .002 | 0.01 | NS | 1.71 | .1.65 | NS |

| Metabolic process | 1.59 | .006 | 0.06 | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| (B) Curated and published lists | |||||||

| TYCKO_UP_IN_WT1_WILDTYPE_WT | -1.68 | <.001 | 0.01 | -1.71 | -1.55 | 1.50 | 1.51 |

| TYCKO_UP_IN_WT1_MUT_WT | 1.40 | .002 | 0.13 | 1.5 | 1.49 | -1.41 | -1.54 |

| ZIRN_UP_IN_CTNNB1_MUT_WT | 1.60 | <.001 | 0.03 | 1.58 | 1.74 | -1.49 | NS |

| ZIRN_DOWN_IN_CTNNB1_MUT_WT | -1.66 | .004 | 0.01 | -1.79 | NS | NS | NS |

| STANFORD_WNT_GENES_UP | 1.86 | <.001 | 0.01 | 1.92 | 1.76 | -1.67 | NS |

| NFATPATHWAY | 1.80 | <.001 | 0.06 | NS | 1.70 | -1.82 | NS |

| TGF_BETA_SIGNALING_PATHWAY | 1.51 | .02 | 0.18 | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| (C) Renal developmental gene lists | |||||||

| LIN intermediate mesoderm | 1.6 | .004 | 0.004 | NS | 1.66 | -1.64 | NS |

| Brunskill A: Early MM | 1.58 | .003 | 0.03 | NS | 1.60 | -1.57 | NS |

| Brunskill M, N, O: interstitium | 1.66 | .003 | 0.03 | NS | 1.59 | -1.62 | NS |

Categories of gene lists with an FDR of 20% or less and nominal P ≤ .05.

Individual gene lists and their leading-edge genes are provided in Table W2.

FDR indicates false discovery rate (median of all gene lists in category); NES, nominal enrichment Score (median of all gene lists in category); NOM, nominal P value (median of all gene lists in category);

NS, not significant (P > .05 or FDR > 0.20).

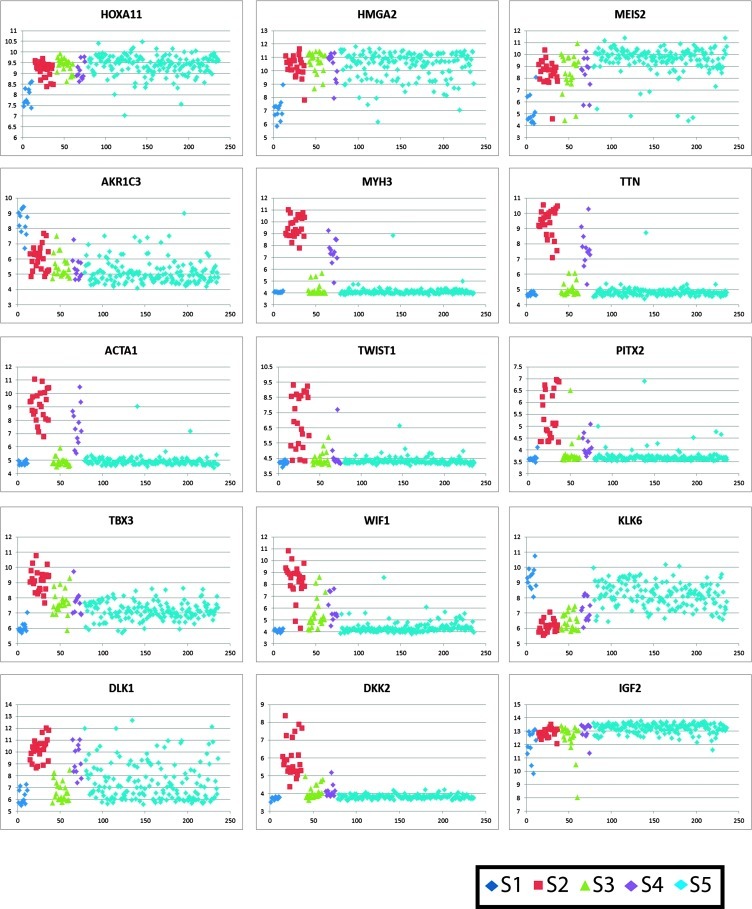

Figure 2.

Patterns of gene expression within the different subsets of FHWT: The log expression levels (low to high) of selected genes are plotted on the y axis. The x axis reflects an arbitrary tumor number, grouping the different tumor types starting with S1 in blue, followed S2 in red, S3 in green, S4 in purple, and the remaining tumors (S5) in turquoise.

S5 tumors, the comparison group for this study, show a pattern of expression previously reported by others in WT [32,36,37]. This includes expression of SIX1, PAX2, EYA1, SALL2, HOXA11*, HOXA9, MEOX1, MEIS2*, PRAME, NNAT, CRABP2, FZD7, COL2A1, GPR64, WASF, HMGA2*, UCHL1, and CCND2, most of which are known to be expressed within the early metanephric mesenchyme (MM). S5 shows gene expression heterogeneity (Figure 1A); however, no expression patterns are sufficiently stable to enable identification or validation. When analyzed alone, S5 tumors did not cluster based on 11p15 methylation, 1p or 16q LOH, nephrogenic rest, presence of muscle differentiation, histologic pattern, or relapse status.

S1 tumors show significantly decreased expression levels of the above renal developmental genes expressed in S5, and negative enrichment of genes expressed in WTs compared with fetal kidney (LI) and genes expressed in the preinduction MM (Brunskill A), illustrated by HMGA2*, MEIS2*, and HOXA11*. Instead, genes expressed subsequent to mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (Brunskill groups D and L) are enriched in S1. Several metabolic processes are significantly enriched in S1 tumors, largely driven by AKR1C3*, a gene expressed in the maturing epithelial component of the developing kidney [29,38]. Similarly, the Notch signaling pathway, key to renal epithelial differentiation, is significantly enriched in S1 tumors. To evaluate whether S1 gene expression was driven solely by epithelial differentiation, four non-S1 tumors with the same histologic pattern were identified from all 224 tumors. They demonstrated different gene expression patterns (red asterisks in Figure 1A), were older at diagnosis (56, 58, 71, and 85 months), and presented at higher stages (one stage I, one stage II, and two stage III tumors) when compared with S1. Two were associated with nephrogenic rests, two of four relapsed, and all demonstrated LOI at 11p15. These features all differ from those of S1 and indicate that the S1 expression profile is not simply a function of epithelial differentiation.

Subset 2 tumors show enrichment of a very large number of GO Biologic Processes gene lists, many of which have in common early muscle development genes, including MYH3* (myosin), TTN* (titin), and ACTA1* (actin), to name a few. Notably, the degree of expression of these muscle-related genes far exceeded the histologic evidence of muscle differentiation in most tumors, which was often quite focal. A wide variety of processes involved in the morphogenesis of other cell types is also enriched. Noteworthy is the increased expression of transcription factors TWIST1* and PITX2*. Both cell proliferation and programmed cell death gene lists are enriched, largely driven by TBX3*, MYC, LGALS1, PLAGL1, FABP7, and IGF1. Signal transduction was likewise enriched, particularly Ras signaling, driven by IGF1. Of the curated canonical pathways, NFAT and TGFB signaling were enriched in S2. This supports the premise previously proposed that WT1 loss may lead to TGFB activation, resulting in NFAT induction, which in turn mediates the switch of TGFB from growth inhibitor to growth promoter [39,40]. The genes differentially expressed between WTs with and without WT1 mutation (TYCKO) are concordantly differentially expressed in S2 tumors, including striking up-regulation of WIF1* and down-regulation of HAS2 and KLK6*. Genes differentially expressed in WT with CTNNB1 mutation (ZIRN) are likewise enriched. Lastly, S2 tumors show significant enrichment of genes normally expressed before induction (LIN intermediate mesoderm, Brunskill group A) and in the renal interstitium (Brunskill groups M, N, and O). Taken together, S2 tumors show evidence of loss of WT1 expression, Wnt activation, and divergent mesenchymal differentiation, all occurring quite early in renal development.

Subset 3 tumors show an overall expression pattern similar to that of S5 (Figure 1A). This is supported by the absence of enrichment of C5 gene ontology biologic processes, C2-curated canonical pathway gene lists, and renal development gene lists analyzed when comparing S3 to S5 (Table 4). However, there are significant differences between S3 and S5. More than 95% of the top genes differentially expressed between S3 and S5 tumors are also coordinately differentially expressed when comparing S2 to S5 (Table W1). Similarly, the gene lists differentially expressed in both WT1 (TYCKO) and CTNNB1 (ZIRN) mutant WT and the Stanford Wnt targets showed the same pattern in S3 and S2 tumors. These observations are consistent with the fact that S3 tumors were identified based on genes coordinately expressed with WT1 and with the observed down-regulation of WT1 in S3 tumors (Figure 1B). Direct comparison of S3 with S2 tumors reveals negative enrichment of most of the same GO categories, canonical pathways, and renal developmental categories previously identified when comparing S2 with S5. In particular, this includes a low expression of genes involved with skeletal muscle differentiation in S3 (Figure 1B), as well as NFAT, TGFB, and Ras signaling. Lastly, whereas S3 tumors show greater canonical Wnt activation than S5 tumors do (NES = 1.9, nominal P < .001, FDR = 1%), there is negative enrichment of Stanford Wnt targets in S3 compared with S2 (NES = -1.67, nominal P < .001, FDR = 0.03). In summary, while similarities between S2 and S3 point toward low WT1 expression, the differences lie in decreased canonical Wnt activation and decreased divergent mesenchymal differentiation in S3 tumors and disruption of S3 tumors later in renal development than that of S2 tumors.

S4 tumors show an overall gene expression pattern quite similar to that of S2 (Figure 1B), and none of the biologic processes, canonical pathways, or renal developmental gene lists are significantly enriched in the comparison of S2 with S4. The one list that differed included genes differentially expressed in tumors with WT1 mutation, which were downregulated in S4 (TYCKO; Table 4). Comparing S4 to S5, more than 95% of the top differentially expressed genes are also concordantly differentially expressed in S2, and S4 shows significant enrichment of many of the same gene lists enriched in S2 compared with S5, including one of two Wnt signaling gene lists (Table 4). Wnt activation was not evident in Figure 1. In summary, the S4 gene expression pattern is quite similar to S2, supporting an origin very early in renal development, although with somewhat less evidence of Wnt activation and WT1 loss.

WT1, CTNNB1, and WTX Mutation Analysis

S1 to S5 show differences in expression of genes associated with WT1 loss and Wnt activation. Therefore, mutation analysis was performed for WT1, CTNNB1, and WTX within S1 to S4 tumors (Table 1). S1 lacks mutations in any of these genes. Whereas ∼50% of S2 and S3 tumors contain abnormalities of WT1, only 10% of S4 tumors contain WT1 genetic events, corresponding to the different enrichment pattern seen in the TYCKO gene lists. The documentation of WT1 mutation in only ∼50% of S2 to S4 tumors that show loss of WT1 expression suggests that other mechanisms for WT1 mRNA loss exist. S2 to S4 show variable evidence of CTNNB1 exon 3 mutations (those known to stabilize β-catenin); the highest frequency is seen in S2, and the lowest, in S4. This parallels the Wnt target expression patterns in these subsets. WTX mutation is identified in 13 (24%) of 53 S2 to S4 tumors and did not vary significantly across these subsets. As previously reported, WTX mutation was associated with CTNNB1 exon 7, 8 mutations [41]. Comparison of gene expression patterns did not show detectable differences when comparing those S2 to S4 tumors with and without WTX mutations (data not shown).

Canonical Wnt Activation

To further investigate Wnt signaling and to determine whether mutation analysis was merited for S5, hierarchical analysis was performed using the Stanford Wnt targets (Figure 1C). S1 tumors cluster together because of increased expression of targets such as LEF1 and FZD2 and decreased expression of CCND1 and JAG1. S2 tumors show strong expression of a large number of canonical Wnt targets including those involved in muscle differentiation (PITX*, ISLR) and extracellular inhibitors of Wnt signaling (WIF1*, DKK1, and DKK2*). Overexpression of these inhibitors has been attributed to cellular resistance to feedback inhibition in the setting of constitutive Wnt activation [42]. Three S2 tumors lacking CTNNB1 or WTX mutations show strong evidence of Wnt activation, suggesting the presence of other mechanisms for canonical Wnt activation, as reviewed previously [43]. S3 and S4 tumors show no clear evidence of canonical Wnt activation and relative decrease in the expression of Wnt inhibitors WIF1*, DKK1, and DKK2*, suggesting insufficient constitutive Wnt activation to trigger this feedback inhibition. S5 lacks overt patterns of differential expression of Wnt targets in these analyses.

11p15 Analysis

Methylation analysis of ICR1 and ICR2 was performed on 205 of 224 tumors with sufficient remaining frozen tissue (Tables 1 and 2). This confirms the presence of tumors with the biallelic paternal but not maternal methylation patterns (Figure 3A). The considerable majority of S1 tumors retain the normal methylation pattern. LOI is rare in S2 and increases in both S3 and S4. In contrast, LOH is high in S2 and decreases in S3. All of the S2 to S4 tumors with 11p15 LOH are disomic by copy number analysis, consistent with UPD. Lastly, the majority of S5 tumors show biallelic methylation of ICR1 resulting from either 11p15 LOH(37.2%) or LOI (43.8%). This does not result in a significant differential expression of IGF2 because IGF2* is highly expressed in virtually all tumors outside S1.

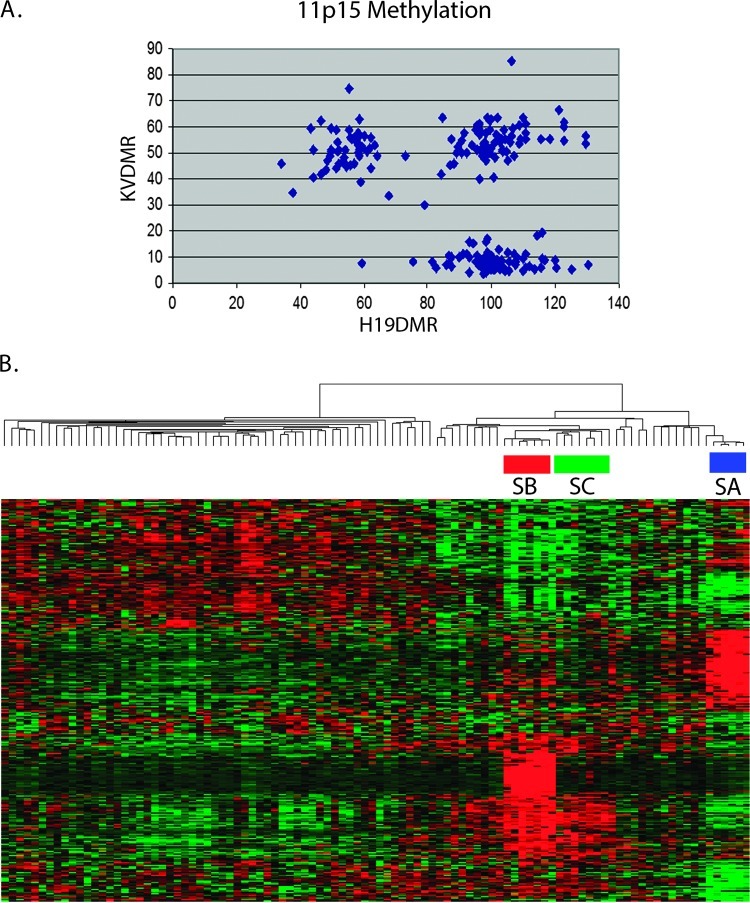

Figure 3.

11p15 methylation and subset validation. (A) ICR1 and ICR2 methylation: Three patterns of methylation were identified: 11p15 LOH (80%–100% methylation of ICR1 and 0%–20% methylation of ICR2), 11p15 LOI (80%–100% methylation of ICR1 and 30%–70% methylation of ICR2), and 11p15 ROI (30%–70% methylation of both ICR1 and ICR2). Tumors with values outside these ranges were not classified. (B) Validation with an independent set of 100 FHWT: Hierarchical analysis was performed using the top genes from Table W1. This demonstrates three subsets of FHWT with the same clinical and pathologic features of S1, S2, and S3 of the training set.

Because 11p15 LOH is usually copy neutral in WT due to UPD, the gene expression consequences of 11p15 LOH and 11p15 LOI are presumed to be largely the same. This is supported by a comparison of S5 tumors with 11p15 LOH versus those with LOI. Significant differential expression of only a few genes was identified, one of which is CDKN1C (fold change [FC] = 0.5, P = 2 x 10-6), whose expression is controlled by ICR2 (with biallelic methylation in LOH). Other genes controlled by ICR2 (PHLDA2, SLC22A1L, KCNQ1DN, KCNQ1, and MTR1) were not significantly differentially expressed, and no other genes of biologic relevance were identified.

1p and 16q LOH

The considerable majority of tumors showing LOH at these two regions reside in S5. S5 tumors did not cluster according to 1p and 16q LOH status.

Validation of Subsets in an Independent Tumor Set

Gene expression and 11p15 methylation analysis were performed on an independent set of 100 tumors from the second group of 300 samples. Hierarchical analysis using the top genes provided in Table W1 demonstrates three subsets of tumors, classified as SA, SB, and SC (Figure 3B). The clinical, pathologic, and 11p15 methylation features of these three subsets, and of the remaining 80 tumors (classified as SD), are provided in Table 2. Subsets A, B, C, and D show the same gene expression and 11p15 methylation patterns, and the same clinicopathologic features as S1, S2, S3, and S5, respectively. An exception is the difference in median age noted between S2 and S3, which was not observed in SB and SC. This is likely a reflection of the broad age ranges seen in S2 and S3 combined with the smaller number of tumors in the validation set (Table 1). Because the top gene lists for S2 and S4 in Table W1 are very similar, it is possible that the above analysis using these lists would not adequately differentiated S2 and S4. To better evaluate for the presence of S4-like tumors within the validation set, we clustered the initial 224 samples combined with the 100 validation samples using the 54 genes associated with WT1 expression (the analysis that detected S4 tumors originally). This resulted in clustering of all SA, SB, and SC tumors with S1, S2, and S3 tumors, respectively (data not shown). None of the validation tumors clustered with S4.

Discussion

Wilms tumors (WT), like most pediatric embryonal neoplasms, have been postulated to arise from cells undergoing differentiation during organogenesis. WT commonly display a triphasic histology remarkably similar to cells at different stages of differentiation of the normal MM: blastemal cells similar to early-stage MM, stromal cells, and epithelialized cells arranged in duct-like structures. This histology and the known clonality of these tumors imply that a cell from which a tumor arises is not only very plastic in its differentiation capacity but that progeny cells can exhibit very different cell fates. The current study has been able to delineate, based on gene expression analysis, distinct subsets of tumors with different molecular, clinical, and pathologic features. These subsets exhibit different mutation patterns as well as different gene expression profiles characteristic of different stages of differentiation. This suggests that tumor subset identity is a result of the interplay of the type of initiating event, the stage of differentiation of the tumor cell of origin, and also its cellular context.

The genitourinary system develops from the intermediate mesoderm, from which the gonads, the mesonephros, and the metanephros (including both the ureteric bud and the primitive MM) develop. Reciprocal interactions between the ureteric bud and the MM are responsible for induction within the MM, which occurs through canonical Wnt signaling. After initiation of induction, mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition begins, enabling the formation of the nephron [44]. Epithelial segmentation, mediated largely by Notch signaling, leads to the development of the glomerular pole proximally and the tubular pole distally. As has been reported previously for WT, most WTs in our study (those of S5) express genes that characterize the MM [32,36,37]. Because the current study analyzes a very large panel of relapse enriched but otherwise unselected WTs for which substantial clinical and molecular information is available, we were able to identify additional subsets of WT with different clinical and pathologic features that show evidence of disruption at different times during normal development. S1 tumors show gene expression patterns similar to the late postinduction epithelial phase of renal development. The gene expression patterns of S2 and S4 show similarities to the intermediate mesoderm or very early MM. S3 and S5, while displaying unique gene expression patterns, do share a profile similar to the MM. To arrive at the ontogeny of WT, these developmental profiles need to be analyzed in conjunction with the genetic events known to be pathogenetically important in WT.

WT1 in Renal Development and in WT

As demonstrated by the Wt1-/- mouse, WT1 expression is low but essential for cell survival within the intermediate mesoderm [2,45]. This is followed by increased WT1 expression in the MM. Somatic ablation of Wt1 in mice soon after nephrogenesis commences results in a block in the formation of epithelial structures [25], consistent with its critical role in the mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition [46]. The expression of WT1 within the different tumor subsets reflects the changing role of WT1 during development as well as the phenotypic effects after its loss, often through mutation. WT1 is highly expressed in S5, in keeping with its expression within the MM, where WT1 is normally highly expressed. WT1 is also highly expressed in S1, in keeping with high WT1 expression normally seen within early epithelial elements. S2 to S4 tumors show low WT1 expression (often because of mutation), which is frequently associated with stromal elements. This is consistent with experimental data demonstrating that loss of WT1 disrupts the normal differentiation of epithelial nephronic elements but has no salient effect on stromal development [25].

Canonical Wnt Activation in Renal Development and in WT

Within the MM, canonical Wnt activation is required for the mesenchymal to epithelial transition to occur; however, subsequent Wnt down-regulation is also required to allow the fully epithelial state of the renal vesicle to develop [47–49]. S1 to S5 tumors show variation in canonical Wnt activation concordant with the timing of their developmental arrest or secondary to genetic changes. No evidence of Wnt activation using these analytic tools is identified in S5, in keeping with their origin around the time of induction. Similarly, S1 tumors show evidence of the canonical Wnt down-regulation required for full epithelial differentiation. Strong constitutive canonical Wnt activation is identified in S2 tumors, with only weak Wnt activation in S3 and S4 tumors, correlating with the incidence of CTNNB1 exon 3 mutation in the subsets (55%, 33%, and 20%, respectively). Canonical Wnt signaling is required for mesenchymal stem cell self-renewal and several of the Wnt pathway genes overexpressed in S2 tumors are mesenchymal stem cell markers, including MET and LGR5 [50,51]. Therefore, for cells of the intermediate mesoderm or early MM that have lost WT1 (and are therefore unable to complete epithelial differentiation as outlined above), constitutive Wnt activation would be predicted to result in the continued blastemal and mesenchymal cell proliferation and development of S2 tumors. WT1 loss somewhat later in development (after the normal reduction of canonical Wnt activation) may be less sensitive to CTNNB1 mutation and require a different secondary genetic event to achieve abnormal proliferation sufficient to result in tumor development, as discussed further below. It is important to note that Wnt signaling is a remarkably complex and cell type- and stage-dependent. Therefore, the above studies do not fully evaluate canonical or noncanonicalWnt signaling in any of the subsets described.

11p15 Alterations in Renal Development and WT

IGF2 expression is high in the undifferentiated MM. After induction, IGF2 is dramatically reduced in the epithelial cells but remains high in the stromal cells [52]. Therefore, the patterns of expression of IGF2 and WT1 during renal development are complementary, and differences in S1 to 5 tumors would therefore be expected. S1 shows retention of the normal methylation pattern at 11p15 and lower IGF2 expression, in keeping with postinduction epithelium. In contrast, S5 tumors show high IGF2 expression, consistent with the very high prevalence of biallelic methylation of ICR1 (81%). S2 to S4 tumors require more careful consideration: 49% of S2 to S4 tumors show evidence of copy neutral 11p15 LOH, known as UPD. UPD occurs when one chromosome (or part thereof) is lost and the second copy is duplicated, usually due to chromosome loss and reduplication or mitotic recombination. In cells that sustain a WT1 mutation in one allele, UPD for chromosome 11 represents a common mechanism for losing the remaining normal WT1 allele. UPD (LOH) at 11p15 will also occur in this situation as an epiphenomenon. Because WTs displaying LOH invariably lose the maternally derived chromosome/chromosome segment [53], WT1 mutant tumors often therefore carry two copies of all paternally imprinted genes. In contrast, the mechanisms that cause 11p15 LOI are confined to 11p15 and can be independent of 11p13 and the WT1 gene. S2 to S4 tumors show an increasing prevalence of 11p15 LOI (4.5%, 19%, and 30%, respectively). LOI was identified in 6 of 16 S2 to S4 tumors lacking CTNNB1 mutations, but in none of the 21 S2 to S4 tumors with CTNNB1 exon 3 mutations. These observations suggest that 11p15-biallelic methylation (either LOH or LOI) may be a second genetic event in the pathogenesis of at least some S2 to S4 tumors and may functionally substitute for CTNNB1 mutations with regard to malignant development. This provides support to a previous study that carefully detailed the 11p15 copy number and methylation analysis, WT1 mutation parameters, and the CTNNB1 status of 36 WT with WT1 alterations provided by Haruta et al. [54]. Interestingly, a mouse model was recently reported that required the introduction of both WT1 mutation and IGF2 overexpression to produce murine WT [25].

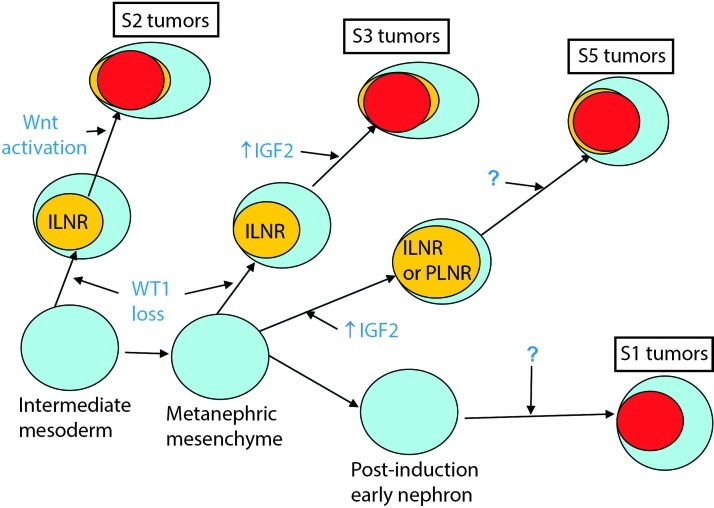

A Revised Model for WT Ontogeny

The most prevalent model for WT development is bifurcated. In one arm, biallelic WT1 mutation results in the development of an ILNR followed by additional genetic changes (e.g., Wnt-activating mutations), resulting in WT development. In the second arm, genetic or epigenetic changes result in biallelic 11p15 ICR1 methylation and development of a PLNR, followed perhaps by additional genetic changes leading to WT development. The data presented in our study confirms these two groups but supports additional heterogeneity that requires revision of this model, as described below (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Revised model for WT ontogeny. See text for description.

Subset 1 tumors are characterized by 1) enrichment of genes expressed in the renal epithelium after induction, 2) high WT1 expression, 3) decreased IGF2 expression, and 4) decreased expression of Wnt targets. They lack WT1, CTNNB1, and WTX mutations, retain heterozygosity for 1p, and 16q, and retain the normal imprinting pattern at 11p15. We propose that S1 tumors arise in the late postinduction MM within a cell characterized by high expression of WT1, low expression of IGF2, and repression of canonicalWnt signaling. S1 tumors do not arise within nephrogenic rests, and the responsible genetic event(s) has not been identified.

Subset 2 tumors show 1) enrichment of genes expressed in the intermediate mesoderm and early MM, 2) loss of WT1 expression often due to WT1 mutation, 3) canonical Wnt activation accompanied by a high CTNNB1-exon 3 mutation frequency, and 4) divergent mesenchymal differentiation, previously attributed to WT1 loss and/or canonical Wnt activation [41,55–58]. In addition, 25% of tumors showed WTX mutation, which has been associated with expansion of early mesenchymal precursors within the developing kidney [59]. We propose that S2 tumors arise within cells of the intermediate mesoderm or early MM after inactivation of one WT1 allele followed by loss of the second WT1 allele, commonly through chromosomal mechanisms resulting in UPD for 11p13. (Incidental UPD for 11p15 also occurs; however, during this developmental window, biallelic expression of IGF2 would not be expected to be as significant because the IGF2 levels are already quite high.) Loss of WT1 perturbs normal nephron development with preferential expansion of mesenchymal elements (which do not require WT1), resulting in an ILNR. Within the ILNR, an additional genetic event (such as CTNNB1 or WTX mutation) results in Wnt activation accompanied by continued proliferation of primitive mesenchymal cells and increased diversion into alternate pathways, including muscle differentiation. The mixed histology observed in S2 tumors supports an origin before the delineation of nephron- or stroma-fated compartments occurs.

Subset 3 tumors show similarities with S2 tumors owing to their common primary pathogenetic feature (low WT1 expression). However, they differ by their decreased evidence of canonical Wnt activation and decreased divergent mesenchymal differentiation. In addition, S3 tumors lack enrichment of genes expressed in the intermediate mesoderm and instead show the same expression of MM genes seen in S5 tumors. We therefore propose that S3 tumors show a similar sequence of genetic events to S2, although these events occur in cells of the MM later in development, at a time when WT1 expression is increasing and IGF2 expression is decreasing. In addition, the different timing is associated with a different sensitivity to (or requirement for)Wnt-activating mutations and therefore to differences in divergent mesenchymal differentiation. Our study provides data supporting the hypothesis previously reported that 11p15 ICR1 biallelic methylation may represent an alternative second event [54].

S4 tumors have a gene expression pattern similar to S2, although they have a lower incidence of WT1, CTNNB1, and WTX mutations (and corresponding expression patterns) and a high incidence of biallelic methylation of ICR1 (80%) similar to S5. Nonetheless, they are defined by their WT1-associated gene expression pattern. These tumors may therefore have alternative genetic/epigenetic abnormalities up- or downstream to WT1. The small number of tumors within this subset and our inability to validate this subset suggests caution is needed with regard to S4. The intriguing clinical and genetic differences, particularly the high relapse rate, support the continued retention of this subset pending further knowledge.

S5 tumors display the gene expression pattern of the MM and a high frequency of biallelic methylation of ICR1 at 11p15. This supports assertions that approximately 70% of WT arise, in part, due to abnormal expression of normally imprinted 11p15 genes [21,23]. It also corroborates an association between an older age at presentation, histologic pattern, and 11p15 LOI in WT [60]. S5 is notable for being the only subset in which PLNRs were observed, although ILNRs were also seen and some tumors contained both. Patients with BWS are known to develop both ILNRs and PLNRs [1]. This suggests that factors such as the cell type or the timing of the initial genetic event may determine the type of nephrogenic rest and the heterogeneous WT histology that results. We propose that S5 tumors arise within cells of the MM at a time when IGF2 expression is diminishing. Biallelic methylation of ICR1 during this developmental window results in increased IGF2 expression and the development of a nephrogenic rest. If biallelic methylation of ICR1 occurs before induction, the persistent elevation of IGF2 causes preferential mesenchymal proliferation and prevents nephron development, resulting in an ILNR. If manifested after induction within early nephronic cells, persistent IGF2 elevation prevents terminal epithelial differentiation, resulting in the development of a PLNR. This is supported by the presence of high WT1 and IGF2 expression in primitive epithelial structures of WT, whereas IGF2 expression is low in normal terminally differentiated epithelial renal elements [52]. Within the resulting nephrogenic rest (be it ILNR or PLNR), a second genetic event likely occurs resulting in tumor development. The absence of tumor development in a mutant mouse strain with biallelic Igf2 expression, but no other genetic alteration, would suggest that a second event is required [25], although the nature of this putative second event in S5 is still unknown.

An important question that remains is whether S5 is a unique entity or simply a conglomeration of tumors that failed to cluster within S1, S2, S3, or S4. Our study accumulates evidence supporting the unity of S5, as outlined below:

More than 80% of S5 tumors show somatic biallelic methylation of ICR1, a constitutional abnormality seen in patients with BWS, which is associated with WT development.

The clinical and pathologic features of tumors arising in patients with BWS (including precursor lesions) are the same as those identified in S5 tumors that are not associated with BWS.

We could not identify other clusters within S5 based on gene expression, even when S1 to S4 were removed.

S5 tumors did not show subclusters based on any clinical or pathologic parameter analyzed in this study.

We have considerable experience observing the variation of gene expression within pathogenetically homogeneous populations of tumors, contrasted with the differences in expression between different tumor types, even when they are histologically similar [31,32,61–63]. The S5 tumors show the range of variation that is expected within a group of tumors that share an underlying pathogenesis.

In summary, while we cannot exclude the presence of biologically distinctive subsets within the larger group of S5 tumors, in our opinion, the prevailing evidence supports the hypothesis that S5 tumors represent a single entity united by their underlying pathogenesis.

Significance

The categorization by gene expression analysis of prospectively identified WTs resulted in the delineation of biologically unique subsets with distinctive mutational spectra and clinical outcomes. Not only does this provide insight into the pathogenesis of these subsets and an explanation for their heterogeneity, but more importantly, defining subsets driven by different genetic events may allow for both subset-specific and targeted therapeutic strategies. Our data suggest that therapies targeting the IGF receptor may be broadly applicable to WT outside S1, whereas the use of therapies involving the Wnt, TGFB, and NFAT pathways, when available, may have activity restricted to particular subsets. The future therapy of infants with low-stage disease will be particularly affected by subset-specific strategies for reducing chemotherapy. Currently, patients younger than 24 months with stage I FHWT weighing less than 550 g are defined as very low risk WT (VLRWT) and are treated with surgery alone. S1 seems to be responsible for approximately 30% of VLRWT who did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy [34,60,64]. In the current study, S1 tumors also occurred in patients older than 24 months, with nephrectomy weights more than 550 g, yet still retained an excellent survival. This may allow for the removal of the arbitrary age and tumor weight restrictions for S1 tumors, thereby expanding the number of patients able to be treated with nephrectomy alone. S2 tumors (likewise common in infants) had an excellent outcome in the current study (in which all patients received adjuvant chemotherapy). In our previous study of VLRWT, when such patients did not receive chemotherapy, there was an increased risk of relapse [34,65], suggesting they may benefit from chemotherapy. Therefore, these studies provide the opportunity to define groups of VLRWT with different relapse risks using appropriate biologic markers that are now being validated using samples from the current protocol.

More globally, our findings illustrate that while pediatric embryonal tumors have a restricted number of genetic events, they cannot be characterized solely by activation of a single gene or pathway. Rather, the clinical and biologic phenotype may be determined in part by the developmental context in which genetic lesions are introduced. In particular, our study highlights considerable complexity with regard to the role of WT1. The impact of WT1 loss seems to change depending on the developmental timing and/or cell of origin of its occurrence, as is seen in S2 and S3 tumors. We provide further evidence suggesting that activation of key signaling pathways (NFAT, TGFB, Ras) is restricted to those subsets arising through loss of WT1 expression quite early in development (S2 and S4). Lastly, our study points toward mechanisms of WT1 loss of expression other than mutation that need to be identified. All these observations are of broad interest, as the critical role of WT1 is increasingly demonstrated to play an important and broad role in development and disease that extends well beyond the kidney [46].

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the technical expertise of Patricia Beezhold and Donna Kersey.

Abbreviations

- WT

Wilms tumor

- ICR1

imprint control region 1

- ICR2

imprint control region 2

- MM

metanephric mesenchyme

- LOI

loss of imprinting

- LOH

loss of heterozygosity

- ROI

retention of imprinting

- UPD

uniparental disomy

Footnotes

This work is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health: U10CA42326 (N.B., D.M.G., E.J.P.). U10CA98543 (J.S.D., P.E.G., E.J.P.), UO1CA88131 (E.J.P., C.C.H.), CA34936 (V.H.), DK069599 (V.H.), CA16672 (V.H.), RP100329 (V.H.), and RP110324 (V.H.).

This article refers to supplementary materials, which are designated by Tables W1 and W2 and are available online at www.neoplasia.com.

References

- 1.Beckwith JB, Kiviat NB, Bonadio JF. Nephrogenic rests, nephroblastomatosis, and the pathogenesis of Wilms' tumor. Pediatr Pathol. 1990;10:1–36. doi: 10.3109/15513819009067094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kreidberg JA, Sariola H, Loring JM, Maeda M, Pelletier J, Housman D, Jaenisch R. WT-1 is required for early kidney development. Cell. 1993;74:679–691. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90515-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scharnhorst V, van der Eb AJ, Jochemsen AG. WT1 proteins: functions in growth and differentiation. Gene. 2001;273:141–161. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00593-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pelletier J, Bruening W, Kashtan CE, Mauer SM, Manivel JC, Striegel JE, Houghton DC, Junien C, Habib R, Fouser L. Germline mutations in the Wilms' tumor suppressor gene are associated with abnormal urogenital development in Denys-Drash syndrome. Cell. 1991;67:437–447. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90194-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Call KM, Glaser T, Ito CY, Buckler AJ, Pelletier J, Haber DA, Rose EA, Kral A, Yeger H, Lewis WH. Isolation and characterization of a zinc finger polypeptide gene at the human chromosome 11 Wilms' tumor locus. Cell. 1990;60:509–520. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90601-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gessler M, Poustka A, Cavenee W, Neve RL, Orkin SH, Bruns GA. Homozygous deletion in Wilms tumours of a zinc-finger gene identified by chromosome jumping. Nature. 1990;343:774–778. doi: 10.1038/343774a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Varanasi R, Bardeesy N, Ghahremani M, Petruzzi MJ, Nowak N, Adam MA, Grundy P, Shows TB, Pelletier J. Fine structure analysis of the WT1 gene in sporadic Wilms tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:3554–3558. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.3554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gessler M, Konig A, Arden K, Grundy P, Orkin S, Sallan S, Peters C, Ruyle S, Mandell J, Li F, et al. Infrequent mutation of the WT1 gene in 77 Wilms' tumors. Hum Mutat. 1994;3:212–222. doi: 10.1002/humu.1380030307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huff V. Wilms tumor genetics. Am J Med Genet. 1998;79:260–267. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19981002)79:4<260::aid-ajmg6>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maiti S, Alam R, Amos CI, Huff V. Frequent association of β-catenin and WT1 mutations in Wilms tumors. Cancer Res. 2000;60:6288–6292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koesters R, Ridder R, Kopp-Schneider A, Betts D, Adams V, Niggli F, Briner J, von Knebel DM. Mutational activation of the β-catenin protooncogene is a common event in the development of Wilms' tumors. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3880–3882. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Major MB, Camp ND, Berndt JD, Yi X, Goldenberg SJ, Hubbert C, Biechele TL, Gingras AC, Zheng N, Maccoss MJ, et al. Wilms tumor suppressor WTX negatively regulates WNT/β-catenin signaling. Science. 2007;316:1043–1046. doi: 10.1126/science/1141515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rivera MN, Kim WJ, Wells J, Driscoll DR, Brannigan BW, Han M, Kim C, Feinberg AP, Gerald WL, Vargas SO, et al. An X chromosome gene, WTX, is commonly inactivated in Wilms tumor. Science. 2007;315:642–645. doi: 10.1126/science.1137509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ruteshouser EC, Robinson SM, Huff V. Wilms tumor genetics: mutations in WT1, WTX, and CTNNB1 account for only about one-third of tumors. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2008;47:461–470. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perotti D, Gamba B, Sardella M, Spreafico F, Terenziani M, Collini P, Pession A, Nantron M, Fossati-Bellani F, Radice P. Functional inactivation of the WTX gene is not a frequent event in Wilms' tumors. Oncogene. 2008;27:4625–4632. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fukuzawa R, Heathcott RW, More HE, Reeve AE. Sequential WT1 and CTNNB1 mutations and alterations of β-catenin localisation in intralobar nephrogenic rests and associated Wilms tumours: two case studies. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60:1013–1016. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2006.043083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Uschkereit C, Perez N, de Torres C, Kuff M, Mora J, Royer-Pokora B. Different CTNNB1 mutations as molecular genetic proof for the independent origin of four Wilms tumours in a patient with a novel germ line WT1 mutation. J Med Genet. 2007;44:393–396. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2006.047530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rainier S, Johnson LA, Dobry CJ, Ping AJ, Grundy PE, Feinberg AP. Relaxation of imprinted genes in human cancer. Nature. 1993;362:747–749. doi: 10.1038/362747a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ping AJ, Reeve AE, Law DJ, Young MR, Boehnke M, Feinberg AP. Genetic linkage of Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome to 11p15. Am J Hum Genet. 1989;44:720–723. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weksberg R, Shen DR, Fei YL, Song QL, Squire J. Disruption of insulin-like growth factor 2 imprinting in Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome. Nat Genet. 1993;5:143–150. doi: 10.1038/ng1093-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ogawa O, Eccles MR, Szeto J, McNoe LA, Yun K, Maw MA, Smith PJ, Reeve AE. Relaxation of insulin-like growth factor II gene imprinting implicated in Wilms' tumour. Nature. 1993;362:749–751. doi: 10.1038/362749a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ohlsson R, Nystrom A, Pfeifer-Ohlsson S, Tohonen V, Hedborg F, Schofield P, Flam F, Ekstrom TJ. IGF2 is parentally imprinted during human embryogenesis and in the Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome. Nat Genet. 1993;4:94–97. doi: 10.1038/ng0593-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steenman MJ, Rainier S, Dobry CJ, Grundy P, Horon IL, Feinberg AP. Loss of imprinting of IGF2 is linked to reduced expression and abnormal methylation of H19 in Wilms' tumour. Nat Genet. 1994;7:433–439. doi: 10.1038/ng0794-433. Erratum in Nat Genet 1994;8:203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chao LY, Huff V, Tomlinson G, Riccardi VM, Strong LC, Saunders GF. Genetic mosaicism in normal tissues of Wilms' tumour patients. Nat Genet. 1993;3:127–131. doi: 10.1038/ng0293-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu Q, Gao F, Tian W, Ruteshouser EC, Wang Y, Lazar J, Strong L, Behringer RR, Huff V. Wt1 ablation and Igf2-up-regulation in mice result in Wilms tumors with elevated ERK1/2 phosphorylation. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:174–183. doi: 10.1172/JCI43772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rahman N, Abidi F, Ford D, Arbour L, Rapley E, Tonin P, Barton D, Batcup G, Berry J, Cotter F, et al. Confirmation of FWT1 as a Wilms' tumour susceptibility gene and phenotypic characteristics of Wilms' tumour attributable to FWT1. Hum Genet. 1998;103:547–556. doi: 10.1007/pl00008708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.MacDonald JM, Douglass EC, Fisher R, Geiser CF, Krill CE, Strong LC, Virshup D, Huff V. Linkage of familial Wilms' tumor predisposition to chromosome 19 and a two-locus model for the etiology of familial tumors. Cancer Res. 1998;58:1387–1390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grundy PE, Breslow NE, Li S, Perlman E, Beckwith JB, Ritchey ML, Shamberger RC, Haase GM, D'Angio GJ, Donaldson M, et al. Loss of heterozygosity for chromosomes 1p and 16q is an adverse prognostic factor in favorable-histology Wilms tumor: a report from the National Wilms Tumor Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7312–7321. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.2799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brunskill EW, Aronow BJ, Georgas K, Rumballe B, Valerius MT, Aronow J, Kaimal V, Jegga AG, Yu J, Grimmond S, et al. Atlas of gene expression in the developing kidney at microanatomic resolution. Dev Cell. 2008;15:781–791. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin SA, Kolle G, Grimmond S, Zhou Q, Doust E, Little MH, Aronow BJ, Ricardo SD, Pera MF, Bertram JF, et al. Subfractionation of differentiating human embryonic stem cell populations allows the isolation of a mesodermal population enriched for intermediate mesoderm and putative renal progenitors. Stem Cells Dev. 2010;19:1637–1648. doi: 10.1089/scd.2010.0017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang CC, Gadd S, Breslow NB, Cutcliffe C, Sredni S, Helenowski IB, Dome JS, Grundy PE, Green DM, Fritsch MK, et al. Predicting relapse in favorable histology Wilms tumor using gene expression analysis. A report from the renal tumor committee of the Children's Oncology Group. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:1770–1778. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang CC, Cutcliffe C, Coffin C, Sorensen PH, Beckwith JB, Perlman EJ. Classification of malignant pediatric renal tumors by gene expression. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2006;46:728–738. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eisen MB, Spellman PT, Brown PO, Botstein D. Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression patterns. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:14863–14868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perlman EJ, Grundy PE, Anderson JR, Jennings LJ, Green DM, Dome JS, Shamberger RC, Ruteshouser EC, Huff V. WT1 mutation and 11P15 loss of heterozygosity predict relapse in very low-risk Wilms tumors treated with surgery alone: a Children's Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:698–703. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.5192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huff V, Jaffe N, Saunders GF, Strong LC, Villalba F, Ruteshouser EC. WT1 exon 1 deletion/insertion mutations in Wilms tumor patients, associated with di- and trinucleotide repeats and deletion hotspot consensus sequences. Am J Hum Genet. 1995;56:84–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li CM, Guo M, Borczuk A, Powell CA, Wei M, Thaker HM, Friedman R, Klein U, Tycko B. Gene expression in Wilms' tumor mimics the earliest committed stage in the metanephric mesenchymal-epithelial transition. Am J Pathol. 2002;160:2181–2190. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61166-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dekel B, Metsuyanim S, Schmidt-Ott KM, Fridman E, Jacob-Hirsch J, Simon A, Pinthus J, Mor Y, Barasch J, Amariglio N, et al. Multiple imprinted and stemness genes provide a link between normal and tumor progenitor cells of the developing human kidney. Cancer Res. 2006;66:6040–6049. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Azzarello JT, Lin HK, Gherezghiher A, Zakharov V, Yu Z, Kropp BP, Culkin DJ, Penning TM, Fung KM. Expression of AKR1C3 in renal cell carcinoma, papillary urothelial carcinoma, and Wilms' tumor. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2009;3:147–155. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dey BR, Sukhatme VP, Roberts AB, Sporn MB, Rauscher FG, III, Kim SJ. Repression of the transforming growth factor-β 1 gene by the Wilms' tumor suppressor WT1 gene product. Mol Endocrinol. 1994;8:595–602. doi: 10.1210/mend.8.5.8058069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Singh G, Singh SK, Konig A, Reutlinger K, Nye MD, Adhikary T, Eilers M, Gress TM, Fernandez-Zapico ME, Ellenrieder V. Sequential activation of NFAT and c-Myc transcription factors mediates the TGF-β switch from a suppressor to a promoter of cancer cell proliferation. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:27241–27250. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.100438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fukuzawa R, Anaka MR, Weeks RJ, Morison IM, Reeve AE. Canonical WNT signalling determines lineage specificity in Wilms tumour. Oncogene. 2009;28:1063–1075. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li CM, Kim CE, Margolin AA, Guo M, Zhu J, Mason JM, Hensle TW, Murty VV, Grundy PE, Fearon ER, et al. CTNNB1 mutations and overexpression of Wnt/β-catenin target genes in WT1-mutant Wilms' tumors. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:1943–1953. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63246-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Corbin M, de Reynies A, Rickman DS, Berrebi D, Boccon-Gibod L, Cohen-Gogo S, Fabre M, Jaubert F, Faussillon M, Yilmaz F, et al. WNT/β-catenin pathway activation in Wilms tumors: a unifying mechanism with multiple entries? Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2009;48:816–827. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schwab K, Patterson LT, Aronow BJ, Luckas R, Liang HC, Potter SS. A catalogue of gene expression in the developing kidney. Kidney Int. 2003;64:1588–1604. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moore AW, McInnes L, Kreidberg J, Hastie ND, Schedl A. YAC complementation shows a requirement for Wt1 in the development of epicardium, adrenal gland and throughout nephrogenesis. Development. 1999;126:1845–1857. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.9.1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miller-Hodges E, Hohenstein P. WT1 in disease: shifting the epithelial-mesenchymal balance. J Pathol. 2012;226:229–240. doi: 10.1002/path.2977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Park JS, Valerius MT, McMahon AP. Wnt/β-catenin signaling regulates nephron induction during mouse kidney development. Development. 2007;134:2533–2539. doi: 10.1242/dev.006155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Iglesias DM, Hueber PA, Chu L, Campbell R, Patenaude AM, Dziarmaga AJ, Quinlan J, Mohamed O, Dufort D, Goodyer PR. Canonical WNT signaling during kidney development. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;293:F494–F500. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00416.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schmidt-Ott KM, Masckauchan TN, Chen X, Hirsh BJ, Sarkar A, Yang J, Paragas N, Wallace VA, Dufort D, Pavlidis P, et al. β-Catenin/TCF/Lef controls a differentiation-associated transcriptional program in renal epithelial progenitors. Development. 2007;134:3177–3190. doi: 10.1242/dev.006544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Etheridge SL, Spencer GJ, Heath DJ, Genever PG. Expression profiling and functional analysis of wnt signaling mechanisms in mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2004;22:849–860. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.22-5-849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lindsley RC, Gill JG, Kyba M, Murphy TL, Murphy KM. Canonical Wnt signaling is required for development of embryonic stem cell-derived mesoderm. Development. 2006;133:3787–3796. doi: 10.1242/dev.02551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yun K, Molenaar AJ, Fiedler AM, Mark AJ, Eccles MR, Becroft DM, Reeve AE. Insulin-like growth factor II messenger ribonucleic acid expression in Wilms tumor, nephrogenic rest, and kidney. Lab Invest. 1993;69:603–615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schroeder WT, Chao LY, Dao DD, Strong LC, Pathak S, Riccardi V, Lewis WH, Saunders GF. Nonrandom loss of maternal chromosome 11 alleles in Wilms tumors. Am J Hum Genet. 1987;40:413–420. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Haruta M, Arai Y, Sugawara W, Watanabe N, Honda S, Ohshima J, Soejima H, Nakadate H, Okita H, Hata J, et al. Duplication of paternal IGF2 or loss of maternal IGF2 imprinting occurs in half of Wilms tumors with various structural WT1 abnormalities. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2008;47:712–727. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schumacher V, Schneider S, Figge A, Wildhardt G, Harms D, Schmidt D, Weirich A, Ludwig R, Royer-Pokora B. Correlation of germ-line mutations and two-hit inactivation of the WT1 gene with Wilms tumors of stromal-predominant histology. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3972–3977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Miyagawa K, Kent J, Moore A, Charlieu JP, Little MH, Williamson KA, Kelsey A, Brown KW, Hassam S, Briner J, et al. Loss of WT1 function leads to ectopic myogenesis in Wilms' tumour [letter] Nat Genet. 1998;18:15–17. doi: 10.1038/ng0198-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fukuzawa R, Breslow NE, Morison IM, Dwyer P, Kusafuka T, Kobayashi Y, Becroft DM, Beckwith JB, Perlman EJ, Reeve AE. Epigenetic differences between Wilms' tumours in white and East-Asian children. Lancet. 2004;363:446–451. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15491-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fukuzawa R, Heathcott RW, Sano M, Morison IM, Yun K, Reeve AE. Myogenesis in Wilms' tumors is associated with mutations of the WT1 gene and activation of Bcl-2 and the Wnt signaling pathway. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2004;7:125–137. doi: 10.1007/s10024-003-3023-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Moisan A, Rivera MN, Lotinun S, Akhavanfard S, Coffman EJ, Cook EB, Stoykova S, Mukherjee S, Schoonmaker JA, Burger A, et al. The WTX tumor suppressor regulates mesenchymal progenitor cell fate specification. Dev Cell. 2011;20:583–596. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ravenel JD, Broman KW, Perlman EJ, Niemitz EL, Jayawardena TM, Bell DW, Haber DA, Uejima H, Feinberg AP. Loss of imprinting of insulin-like growth factor-II (IGF2) gene in distinguishing specific biologic subtypes of Wilms tumor. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:1698–1703. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.22.1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cutcliff C, Kersey D, Huang CC, Hasan C, Walterhouse D, Perlman EJ. Clear cell sarcoma of the kidney: up-regulation of neural markers with activation of the sonic hedgehog and Akt pathways. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:7986–7994. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gadd S, Beezhold P, Jennings L, George D, Leuer K, Huang CC, Huff V, Tognon C, Sorensen PH, Triche T, et al. Mediators of receptor tyrosine kinase activation in infantile fibrosarcoma: a Children's Oncology Group study. J Pathol. doi: 10.1002/path.4010. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gadd S, Sredni ST, Huang CC, Perlman EJ. Rhabdoid tumor: gene expression clues to pathogenesis and potential therapeutic targets. Lab Invest. 2010;90:724–738. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2010.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]