Abstract

As part of a study of 198 residents with low vision in 28 nursing homes, 91 participated in a low vision rehabilitation intervention. Among the rehabilitation participants, 78% received simple environmental modifications, such as lighting; 75% received low vision instruction; 73% benefited from staff training; and 69% received simple nonoptical devices. Because of the cognitive and physical fragility of many nursing home residents, the authors recommend an approach that centers on training nursing home staff and improving the environment of the facilities, especially in the area of illumination.

Visual impairment (that is, blindness or low vision) increases dramatically with age, such that an estimated 250,000 new cases are reported annually among persons aged 65 and older in the United States (Massof, 2002). Furthermore, in the United States, the prevalence of individuals with a visual acuity of worse than 20/40 is 2.76%, with increasing prevalence with age (Eye Diseases Prevalence Group, 2004). Individuals who are blind or have low vision encounter increased difficulty maintaining their independence in a variety of areas, including activities of daily living (ADLs) and mobility (Rubin, Roche, Prasada-Rao, & Fried, 1994; Watson, 2001). Although low vision is not correctable, rehabilitation services can improve functioning in those who have it. These services are not mandated by law, despite the great need. However, the increased prevalence of vision loss and the need for low vision rehabilitation prompted the U.S. National Institutes of Health (2000) to include low vision rehabilitation services as one of its goals for its program Healthy People 2010, which is a national health promotion and disease prevention initiative that challenges individuals, communities, and professionals to take specific steps to ensure increased quality and years of healthy life and eliminate health disparities among people in the United States.

If a community does not have low vision specialists, access to low vision rehabilitation is difficult for that community's older persons who may have to travel great distances for treatment. As the population ages and the number of nursing home residents with low vision rises, the rehabilitation needs of this population will increase (Horowitz, 1994; Mitchell, Hayes, & Wang, 1997). Federally funded programs, such as the Aid to the Independent Elderly Blind, which is intended to maintain the independence of elderly people in their current living situations, specifically exclude nursing home facilities. Services that do exist for nursing home residents with low vision are limited. An example of such a service is the Talking Book program of the National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped, Library of Congress, which some nursing home facilities use. Services may not be based on an assessment of the residents’ level of function and the tasks for which vision is needed.

The literature on the prevalence of low vision and the associated deficit of performance on ADLs by institutionalized adults describes the impact of low vision (De Winter, Hoyng, Froeling, Meulendijks, & Van der Wilt, 2004; Marx, Werner, Cohen-Mansfield, & Feldman, 1992). De Winter et al. compared the function of elderly nursing home residents who had low vision devices and those who did not have low vision devices, but the sample was too small to detect significant differences. Marx et al. surveyed 103 nursing home residents with good cognition and found that a significantly greater proportion of residents with low vision than of those with good vision were dependent on caregivers for performing ADLs. No age adjustment was done in this sample, and it was unclear whether the residents had received any rehabilitation as part of the study.

In the context of a clinical trial of vision restoration and rehabilitation services for nursing home residents, we provided low vision services to residents in randomly selected nursing homes. The low vision specialist for this study, the first author, has a master's degree in rehabilitation of persons who are visually impaired and is a certified low vision therapist. The low vision intervention presented in this article was a component of a larger intervention, the Salisbury Eye Evaluation in Nursing Home Groups (SEEING) Study, that included ophthalmologic screening, examination, refraction, and cataract surgery when appropriate; this process was described in more detail in an earlier publication (West et al., 2003). This article describes the characteristics of residents in 28 nursing homes on the Eastern Shore of Maryland and Delaware who were found to have low vision, the proportion of these residents who agreed to low vision rehabilitation or other types of intervention, and the residents’ need for and goals of low vision rehabilitation.

Methods

The 28 nursing homes were stratified by size (number of beds) and the proportion of residents who paid for services and were randomized into one of two groups: intervention and usual-care homes. Residents in “intervention homes” received, free of charge, full ophthalmic exams, cataract surgery, glasses, or low vision rehabilitation services depending on the recommendations of the study ophthalmologist (the third author). Residents in “usual-care homes” received full ophthalmic exams, and the recommendations of the ophthalmologist were presented to the guardians and care providers of the residents. Residents in either group of homes were eligible for the study if they were aged 65 or older, had a life expectancy of 6 months or more, and were not in a short-term placement (30 days or fewer). Residents who were completely unresponsive to all stimuli or were in an immediately terminally ill condition were not eligible. The research followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. Consent was obtained for each participant as a condition for entering the protocol. Consent was provided by the participants if they were cognitively able or by their designated care providers or family members if the participants were cognitively impaired.

Habitual and best-corrected acuity was attempted on all eligible residents using standard letter or symbol charts and grating acuity charts in each eye separately (Friedman et al., 2004). If habitual visual acuity was worse than 20/40 in the better-seeing eye, a subjective refraction was attempted. The third author, an ophthalmologist, provided an examination for those with best-corrected visual acuity worse than 20/40 in the better-seeing eye. In the usual-care homes, the ophthalmologist reported the results of the examination to the nursing home physician and to the participant or the participant's guardian; the participant or family member obtained eye care treatment at his or her discretion. In the intervention homes, residents with acuities worse than 20/40 were offered one of three interventions: eyeglasses, cataract surgery, or low vision rehabilitation on the basis of the ophthalmologist's recommendation. The SEEING project staff provided these services at no cost to the participants or the facility. Details are described in a previous publication (Friedman, Muñoz, Massof, Bandeen-Roche, & West, 2002). For all the nursing homes, the case group was composed of residents whose acuities were worse than 20/40 (those with low vision). The control group was made up of residents who were matched to each case by age (within five years), gender, and nursing home, but who had presenting acuities of 20/40 or better (those who were not visually impaired).

At the baseline visit, the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) was attempted with all the participants as a measure of cognition. Questionnaires were used to assess the functional status of the cases and matched controls for 11 recreational activities (frequency of reading, watching television, playing card games, knitting or sewing, walking or wheeling outdoors, exercising or sports, taking trips or doing shopping, gardening, singing or listening to music, participating in religious activities, and helping others), 4 mobility levels (level of independence when moving from a lying position, moving between objects in a room, walking between locations in a room, and walking in the corridor), 5 ADLs (level of independence when putting on clothes, eating, using the bathroom, maintaining personal hygiene, and taking a bath or shower), and 4 questions on socialization (recognizing faces, game pieces, and clocks or time and avoiding embarrassing situations). The questions were asked of the nursing home staff who knew the participants (West et al., 2003). This methodology was used in previous studies of nursing home residents who may be unreliable respondents (German, Rovner, Burton, Brant, & Clark, 1992).

The criterion for low vision rehabilitation services was a best-corrected visual acuity worse than 20/40, including those who refused cataract surgery and were left with low vision. Intervention was attempted on all the participants with low vision (in the intervention homes), regardless of cognitive function. Even participants who might not benefit from low vision intervention (according to the nursing home staff because of cognitive limitations or who had MMSE scores of less than 18) were included in the initial evaluation process at the request of the rehabilitation specialist. Participants who were visually impaired but did not qualify for the low vision arm of the study either had a best-corrected acuity in the better eye of 20/40 or better (correctable with eyeglasses), or were eligible for cataract surgery.

A low vision rehabilitation specialist (JD) provided the initial evaluation of a participant's need and goals for low vision intervention, and the study optometrist (WP) measured the participant's need for a change of eyeglasses as part of the initial low vision assessment. Lighting levels were measured in the initial study homes; levels were approximately 15–20 foot-candles (fc) of ambient lighting in the participants’ rooms, and the participants used ambient light for near tasks because their rooms were not equipped with additional lighting. Recommended levels of ambient light in senior rooms are 30 fc, but 75 fc, and 50 fc, respectively, for tasks such as reading and kitchen-type work (including the administration of medication) (Illuminating Engineering Society of North America, 1998).

Goals for low vision rehabilitation were established in conjunction with the participants, family members (when available), and staff members of the nursing home facility. Goals were assessed in a questionnaire format that was administered verbally to a participant by the rehabilitation specialist. The assessment determined whether the participant had any goals for independent function in a particular domain; the participant's current level of function was also assessed. Domains included 5 ADLs: dressing, bathing, toilet use, eating, and transfers or movement from one location to another, such as from a bed to a wheelchair; 3 mobility activities: ambulating around the room or bathroom, around the corridors or common areas, and outside the nursing home; 3 solitary recreational activities: reading, watching television, and playing solitary games or puzzles; and socialization (such as recognizing faces, game pieces, and clocks and avoiding embarrassment). The levels of independent function for the mobility and ADL domains were as follows: independent with no help, supervision or cuing or setup help only, limited assistance or guided maneuvering of limbs, and extensive help. Because of the amount of support and activity they gave the participants, the recreational specialists in the nursing homes often provided most of the information about the individual participants’ goals and needs.

In the intervention homes, follow-up service was provided, including rehabilitation instruction to address goals, on an individual basis with up to five hours of follow-up services. Low vision equipment, including optical and illumination equipment, was prescribed by the low vision optometrist in consultation with the low vision specialist and was provided at no cost to the participants. Low vision interventions were directed to both the participants and the staff of the facilities. For this project, all nursing home facilities were provided a one-hour in-service presentation on low vision rehabilitation and its functional implications as part of the intervention process, and a video was given to the facilities for staff members who were unable to attend the presentation. If the low vision specialist determined that a nursing home facility needed further modification for the participants with low vision, that recommendation was made to the facility, and intervention was provided.

Statistical analysis

We compared the demographic characteristics, cognitive characteristics, and functional status of those who were initially assigned to the low vision group with those of the non-visually impaired persons in the control group and those who were initially assigned to other interventions. Independent mobility function was defined as being free from staff help or supervisory help only, the number of recreational activities was defined as the number of different recreational activities that were performed within a typical week, and the number of independent ADLs was defined as the number of ADLs that were performed with no staff help or supervisory help only. The initial assignment to an intervention was based on the ophthalmologist's recommendation; however, participants were free to refuse an intervention and to be reassigned (for instance, participants who refused cataract surgery were reassigned to the low vision intervention). All statistical comparisons were adjusted for age and the correlation among participants in a nursing home (which was accounted for with the use of generalized estimating equations) (Liang & Zeger, 1986). Statistical comparisons of functional status were adjusted for age and cognitive status (MMSE score) and the correlation among participants in a nursing home.

The initial descriptive analysis of the goals of low vision rehabilitation revealed that a small percentage of the participants with low vision had no goals in any areas. We explored the reasons for having no goals by comparing those with goals in specific areas to those with no goals. Statistical comparisons were not done because of the small number of participants who had any goals in the ADL and mobility domains.

Results

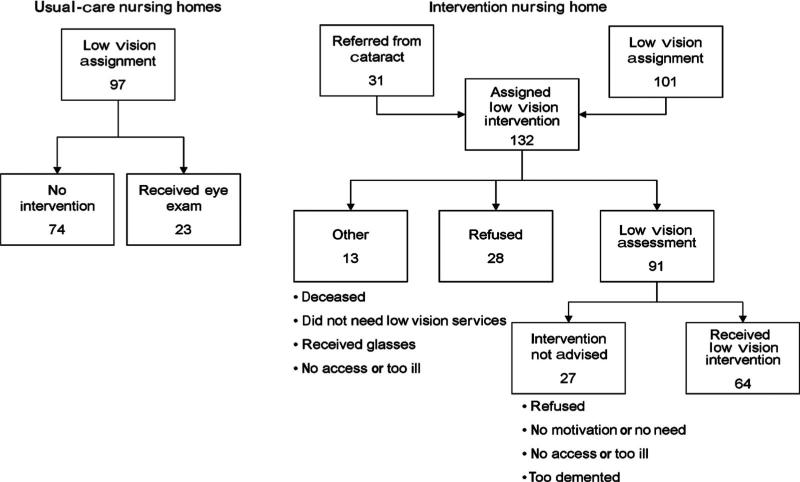

Originally, 496 individuals were identified as having low vision and considered to be viable participants for the study. A total of 457 non-visually impaired persons in the control group were matched by age, gender, and nursing home to these cases, but the number of these persons was lower because some cases were too old to find a matching control. Later, 90 cases were dropped from the case group when the cause of their visual impairment was undetermined. The ophthalmologist initially assigned 198 nursing home participants to low vision rehabilitation, in both the intervention nursing homes and usual-care homes (see Figure 1). An additional 31 visually impaired participants in the intervention homes declined to have cataract surgery and were eligible for the low vision arm of the study.

Figure 1.

Low vision outcomes.

The characteristics of the participants who were initially assigned to low vision intervention were different from those of the control group (with no visual impairment). Those who were assigned to the low vision intervention were older, had lower MMSE scores, and had been in the nursing home facility longer (see Table 1). The cognition of the participants who were referred to low vision rehabilitation was low, with 72.2% scoring lower than 18 on the MMSE. The participants with low vision tended to participate in fewer ADLs and were less able to move around independently than were those in the control group.

Table 1.

Initial assignment to the low vision group compared with the control group and other assignments.

| Characteristic | Nonvisually impaired (control group) n = 457 (%) | Initial assignment to the low visiongroup n = 198 (%) | Initial assignment to another intervention n = 208 (%) | Nonvisually impaired versus the low vision group z-score, pa | Another intervention versus the low vision group z-score, pa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||||

| <80 | 138 (30.2) | 41 (20.7) | 52 (25.0) | <.0001 | .10 |

| 80–89 | 229 (50.1) | 74 (37.4) | 76 (36.5) | ||

| >=90 | 90 (19.7) | 83 (41.9) | 80 (38.5) | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 344 (75.3) | 150 (75.8) | 166 (79.8) | .07 | .04 |

| Male | 113 (24.7) | 48 (24.2) | 42 (20.2) | ||

| Race | |||||

| White | 359 (78.6) | 162 (81.8) | 147 (70.7) | ||

| Black | 95 (20.8) | 35 (17.7) | 60 (28.8) | .87 | .02 |

| Otherb | 3 (0.7) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | ||

| Presenting acuity | |||||

| >=20/40 | 390 (85.3) | — | — | — | <.0001 |

| 20/41–20/42 | 67 (14.7) | 11 (5.6) | 15 (7.2) | ||

| 20/100–20/199 | — | 39 (19.7) | 18 (8.6) | ||

| < = 20/200 | — | 38 (19.2) | 10 (4.8) | ||

| Score on MMSE | |||||

| <18 | 270 (59.1) | 143 (72.2) | 146 (70.2) | <.0001 | .49 |

| >=18 | 182 (39.8) | 51 (25.8) | 55 (26.4) | ||

| Length of stay | |||||

| <1 year | 196 (42.9) | 60 (30.3) | 52 (25.0) | .0004 | .26 |

| 1–2 years | 102 (22.3) | 44 (22.2) | 44 (21.2) | ||

| >2 years | 159 (34.8) | 94 (47.5) | 112 (53.9) | ||

| Recreational activitiesc | |||||

| 0–1 | 100 (21.9) | 62 (31.3) | 58 (27.9) | .0004 | .02 |

| 2–4 | 196 (42.9) | 90 (45.4) | 86 (41.4) | ||

| 5–11 | 159 (34.8) | 46 (23.2) | 64 (30.8) | ||

| Independent mobilityc | |||||

| Within corridor | 190 (41.8) | 53 (26.8) | 61 (29.3) | .03 | .36 |

| Within room | 57 (12.5) | 15 (7.6) | 22 (10.6) | ||

| In bed only | 60 (13.2) | 35 (17.7) | 29 (13.9) | ||

| None | 148 (32.5) | 95 (48.0) | 96 (46.2) | ||

| Independent ADLs | |||||

| 0 | 68 (15.0) | 59 (29.8) | 57 (27.4) | .01 | .53 |

| 1 | 164 (36.0) | 77 (38.9) | 81 (38.9) | ||

| 2–3 | 97 (21.3) | 21 (10.6) | 39 (18.8) | ||

| 4–5 | 126 (27.7) | 41 (20.7) | 31 (14.9) | ||

| Visits to or from friend or family membersc | |||||

| <1 per week | 93 (20.5) | 38 (19.4) | 37 (17.8) | .73 | .40 |

| 1–2 per week | 93 (20.5) | 39 (19.9) | 40 (19.2) | ||

| 3–5 per week | 153 (33.8) | 62 (31.6) | 53 (25.5) | ||

| Almost daily | 114 (25.2) | 57 (29.1) | 78 (37.5) |

Note: MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination.

Accounting for the within-nursing home correlation and age adjusting.

Category not included in significance testing.

Also adjusting for the MMSE score; independent mobility describes being mostly free of staff assistance.

The characteristics of the participants who were initially assigned to low vision services were similar to those of the participants with low vision who were initially assigned to other interventions (see Table 1). Although the ages, MMSE scores, and lengths of stay of the participants in the two groups were similar, those who were assigned to low vision services were slightly more likely to be male and Caucasian than were those who were assigned to other interventions. The majority of participants who were assigned to low vision services (79.3%) were aged 80 or older. The distance acuity of those in the low vision services group, using habitual correction (presenting acuity), was significantly worse than that of the participants who were assigned to other interventions. Those who met the definition of legal blindness (a best-corrected visual acuity of 20/200 or worse or a visual field restriction of 20 degrees or less) accounted for 19.2% of the initial assignment, with almost half the participants who were assigned to low vision services (48.5%) having acuities between 20/60 and 20/99. The participants who were assigned to other interventions participated in more ADLs than did those who were assigned to low vision services, but had a similar independent mobility status.

For the 132 participants with low vision whose nursing home was randomized to low vision intervention, of those who were assigned to low vision intervention (including the 31 who declined to have cataract surgery), 91 (68.9%) received a low vision assessment, 28 (21.2%) declined an assessment, and 13 (9.9%) were deemed by the low vision specialist to be too cognitively impaired or ill to receive an assessment (see Figure 1).

Among those who received a low vision assessment, 42 (46.2%) needed the help of staff members for any mobility task, and 24 (26.4%) did not perform any ADL activity independent of help from the staff members. The needs of these participants involving independence in ADLs were centered on eating (10, or 11% of those who were assessed had some eating goal), with no need expressed in the areas of personal care, such as toilet use, dressing, and bathing. Participants who had goals for improved eating tended to be younger and had either fairly good acuity or extremely poor acuity (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the participants in the low vision assessment, by their rehabilitation goals (n = 89; 2 responses missing).

| Characteristic | Number | Percent with at least one eating goal | Percent with at least one independent mobility goal | Percent with at least one recreational goal | Percent with at least one social activity goal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||||

| <80 | 19 | 21.0 | 10.5 | 84.2 | 57.9 |

| 80–89 | 34 | 8.8 | 2.9 | 44.1 | 36.4 |

| >= 90 | 36 | 8.3 | 5.7 | 44.4 | 44.4 |

| MMSE | |||||

| <18 | 62 | 11.3 | 1.6 | 43.6 | 38.7 |

| >18 | 26 | 11.5 | 16.0 | 73.1 | 56.0 |

| Presenting acuity | |||||

| 20/40–20/59 | 12 | 14.3 | 7.7 | 64.3 | 57.1 |

| 20/60–20/99 | 48 | 6.3 | 4.2 | 45.8 | 27.7 |

| 20/100 + | 27 | 18.5 | 7.4 | 59.3 | 66.7 |

| Require assistive device? | |||||

| No | 24 | 8.3 | 4.2 | 33.3 | 29.2 |

| Yes | 65 | 12.3 | 6.3 | 60.0 | 50.0 |

| Recreational activities | |||||

| 0–1 | 32 | 13.6 | 6.2 | 46.9 | 41.9 |

| 2–4 | 31 | 4.5 | 3.3 | 51.6 | 51.6 |

| 5–11 | 26 | 12.5 | 7.7 | 61.5 | 38.5 |

| Visits to or from friends or family | |||||

| <1/week | 23 | 8.7 | 4.5 | 43.5 | 31.8 |

| 1–2/week | 13 | 7.7 | 0.0 | 69.2 | 61.5 |

| 3/week | 28 | 17.9 | 10.7 | 67.9 | 57.1 |

| Almost daily | 23 | 8.7 | 4.4 | 34.8 | 34.8 |

| Patient bedfast all or most of the time? | |||||

| Yes | 9 | 11.1 | 0.0 | 55.6 | 50.0 |

| No | 80 | 11.2 | 6.3 | 52.5 | 43.8 |

| Low vision recommendation | |||||

| Low vision rehabilitation | 64 | 15.6 | 7.9 | 71.9 | 59.4 |

| No rehabilitation | 25 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 4.0 | 4.2 |

Note: MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination. Total number with eating goals = 10; total number with independent mobility goals = 5; total number with 1 recreational goal = 21, 2 recreational goals = 16, and 3 recreational goals = 9; total number with 1 social activity goal = 10, 2 social goals = 8, 3 social goals = 15, and 4 social goals = 6.

Of those who were assessed, only 5 (5.6%) had any goals to improve their independence in the area of mobility. The majority of participants with low vision (72.7%) required mobility devices for navigation within the nursing home facility, and many of the devices, such as wheelchairs, required staff assistance. Those who did have mobility goals were slightly younger and had a higher cognitive status (see Table 2).

The 46 (41.7%) participants who had goals to improve the quality of solitary recreational activities (such as reading, watching television, and playing solitary games) tended to be younger and to have higher cognition than those with no goals, but were otherwise similar in age and acuity. The number of ADLs that those with goals already performed tended to be higher than the number performed by those with no goals (see Table 2).

The 39 (43.8%) participants who had goals to improve their socialization abilities related to vision (like recognizing faces and game pieces) tended to have higher cognition. They also tended to have visits from friends and family members a few times per week, whereas those with no goals either had no visits or infrequent visits (see Table 2).

A review of the initial assessment indicated that 64 (70%) of the 91 participants who accepted low vision intervention were deemed eligible to benefit from further training and intervention (see Figure 1). The remaining participants were too demented to use the devices or to receive training (10 of the 91, or 11%) or did not accept the intervention for a variety of reasons, including being too ill, feeling that they did not need an intervention, or choosing to decline the intervention (17 of the 91, or 19%). The low vision specialist assessed not only the participants, but the staff and facility as part of the intervention. His clinical judgment was based on all three parameters. The low vision specialist's most frequent recommendation was a change in the environment of the facility (50 of 64, or 78%) (see Table 3); the recommended change in 40 of these 50 cases (80%) was a change in illumination levels, over which the participants had little control.

Table 3.

Types of recommendations for patients with low vision (n = 64).

| Recommendation | Number |

|---|---|

| Patient rehabilitation | 48 (75.0%) |

| Low vision device prescribed | 44 (68.8%) |

| Training unrelated to low vision device | 18 (28.1%) |

| Staff training | 47 (73.4%) |

| Specific to the patient | 18 (28.1%) |

| General training | 34 (53.1%) |

| Environmental change | 50 (78.1%) |

| Lighting | 40 (62.5) |

| Contrast | 31 (48.4) |

| Safety | 12 (18.8) |

In addition, low vision devices and strategies were also recommended. Of the 64 participants who received low vision intervention (training or low vision devices), 44 (68.8%) received some type of low vision equipment to help them perform their desired goal. Among the 44, 24 received one device, 11 received two devices, 6 received three devices, and three received four devices.

Recreational activities were the leading reason for dispensing low vision optical devices. Binocular sport glasses were the most frequently prescribed device, given so that the participants could watch television; 18 participants received this device (see Table 4). The participants were given eyeglasses if they could not physically position themselves to watch television properly. The second most frequently prescribed optical device was a lamp that helped the participants read the activity chart and menu in the facility. A handheld magnifier was the third most frequently dispensed optical device, with 10 participants receiving magnifiers. Stand magnifiers were also recommended for recreational activities when the participants were unable to work with a hand-held magnifier because of limited hand control. However, the weight of the stand magnifier was a serious issue—because of the weight of the batteries needed to provide adequate illumination, the nursing home residents could not comfortably manipulate the device—so these magnifiers were not as frequently prescribed.

Table 4.

Low vision devices dispensed (n = 76).

| Device | Number |

|---|---|

| Black felt pen | 3 |

| Squeeze light | 1 |

| Bold-lined paper | 5 |

| Handheld magnifier | 10 |

| High-intensity lamp | 15 |

| Prismatic reading glasses | 5 |

| Large-print remote | 3 |

| Large-print playing cards | 3 |

| New glasses with bifocals | 7 |

| Piano safety glasses | 1 |

| Signature guide | 1 |

| Sport glasses | 18 |

| Stand magnifier | 3 |

| Talking Book | 1 |

Modification of lighting was another frequently recommended low vision device and was provided to 15 participants. A floor lamp with a natural light source was found to be the most effective for the participants. Illumination was provided for near tasks, such as eating, reading the activity chart and menu, and looking at photographs of family members. Reading for pleasure made up a small percentage of the recreational goals, with 5 participants having prismatic reading glasses prescribed for this task. Sustained reading was a rare task, so near vision was enhanced for other tasks, such as reading a menu or playing card. New eyeglasses were prescribed to 7 participants, with a bifocal change to enhance the ability to see food while eating.

Discussion

Several key points emerged from this study on providing low vision rehabilitation to nursing home residents. First, the low vision rehabilitation was designed to treat participants individually to meet their individual goals. It was anticipated that many of the participants would benefit from the use of low vision equipment, such as optical devices, to achieve their desired goals. However, the fragility and limited cognitive ability of many participants greatly changed the structure of the framework of the low vision intervention from direct service to consultation with the facilities and personnel with the limited use of optical devices by the nursing home residents who were originally deemed eligible for participation in this study. Our experience suggests that future efforts to provide low vision rehabilitation services for nursing home residents should center on training and improvement within the facility in addition to focusing on participants. An approach that focuses on educating facilities and staff in the needs of nursing home residents with low vision will result in the greater awareness of personnel of the needs of this population as a whole, rather than just the needs of those residents who are receiving low vision rehabilitation.

No studies to date have studied vision interventions in nursing homes. De Winter et al. (2004) found that patients with low vision devices had better VF-14 (self-reported vision-related quality of life) scores than did those who had no devices. However, the study was underpowered to detect significant differences because there were not enough subjects to find a statistically significant difference. In addition, patients with dementia were not included in the study, so an approach to modify the facility was not considered. Similarly, Marx et al. (1992) included only nursing home residents who were not cognitively impaired, which limits the generalizability of their results.

Mobility concerns for nursing home residents have been cited in the literature in relation to falls that are due to diminished vision (Horowitz, 1994). This project documented that most participants who were classified as having low vision did not travel unassisted without support equipment and did not list goals in the area of mobility. In addition, the nursing home staff members raised concerns about safety and the time needed for long-term training in mobility of the few participants who might have become more independent. That the participants who did not specify the goals of improving their mobility may reflect their realistic determination of their potential for rehabilitation in this area. Approximately 77% of this group used wheelchairs or walkers. In most cases, the nursing home staff members assisted them in the operation and navigation of this equipment for safety and expediency. Future work in determining appropriate mobility training for nursing home residents is warranted to better the interaction of the staff members, facilities, and likely independence of the residents.

Tasks involving ADLs, such as eating and dressing, often required the assistance of staff members, and staff members sometimes encouraged the dependence of residents to accomplish tasks more quickly. The participants with low vision had difficulty eating independently in the dining room, since little, if any, adaptive equipment, such as a sectioned plate, was used to help them do so. In most cases, the staff would assist by feeding the participants, rather than instructing them in proper adaptations. Dressing was done with the assistance of staff members, from picking out clothing to actual dressing. The heavy dependence of participants on assistance by staff members may have contributed to the participants’ failure to list these tasks as goals.

Recreational activity was the area in which the participants most often sought low vision rehabilitation. The greatest area of need that the participants expressed was for viewing television. Most participants had television sets in their rooms, usually 21-inch models that were often viewed at a distance of 8 to 10 feet if the participants were bedridden or could not move closer without assistance. In addition, the small rooms impeded those in wheelchairs from gaining a closer viewing distance. In the activity rooms that had television sets for the participants to view in a group setting, the television models were larger, usually about 25 to 32 inches, but the sets were placed in rooms that were multifunctional by design with windows and large amounts of natural lighting. Although the participants would go to these areas to watch television, it was difficult to view the image on the screen in daylight because of excessive glare in the viewing area. Maintaining visual attention was difficult for the participants in this situation, so the participants were relocated to their rooms in most cases to achieve this goal because of competing environmental factors. To enhance television viewing, sport glasses with 2.8× magnification were the most useful low vision device. Once the focus was set, the use of these eyeglasses was similar to that of regular eyeglasses and did not require the help of staff members. The greatest challenge for the participants was locating and retrieving the sport eyeglasses, which sometimes required help from staff members.

The performance of near tasks related to sustained reading was limited within this project. Most participants needed to read the activity schedule and cafeteria menus that were attached to their meal trays or walls of their rooms, rather than to read for sustained periods. The size of the print varied from approximately 18-point to 32-point type. Illuminated magnifiers were the low vision optical devices of choice for the completion of this task.

Proper illumination within the nursing home facilities was the greatest challenge for the participants. As we mentioned earlier, the participants attempted to perform near tasks in their rooms, where the illumination was often inadequate for such tasks. No facility provided a direct light source for the performance of near tasks, such as reading. Lighting, if available, was located above the beds and was typically fluorescent with a shield that would direct the light above and away from the desired task. An alteration in illumination was the most common intervention directed at helping the participants to achieve their near-task goals. Floor-model natural lighting lamps were used to provide the greatest flexibility and directed light source. However, in many cases, the electrical receptacle outlets in the rooms were outdated and needed updating to a three-pronged grounded receptacle to use the floor lamps. The colors of paint in the rooms influenced the impact of illumination. Most rooms were of a neutral color, which would absorb light and hide dirt, rather than a light color, which would reflect light and improve the performance of functional tasks. Activity rooms were just the opposite in most cases. These rooms were large, with one wall of natural light from the windows and a light paint color throughout the rooms. In these areas, the challenge was to reduce glare.

In a facility-based approach, staff involvement in the delivery of low vision rehabilitation services was critical to the success of the services. Some of the obstacles were nursing home facilities that were short staffed or had high levels of turnover, which resulted in the limited involvement by staff members in low vision rehabilitation. We provided an in-service training program for the staff members and videotapes for those who were unable to attend the training program; we made efforts to schedule the training program during the overlap time of the first and second shifts. Compliance in attendance by staff members was directly related to the level of commitment of the administration.

A good deal of staff time was devoted to assisting the participants to eat. If staff shortages were a problem, the staff would not have the time to encourage the participants to eat independently. The participants were assisted with meals to various degrees, depending on the staffing levels and the cognitive ability and level of vision of participants. Assistance provided by staff members included verbal prompting, cutting up food, full feeding, and, in one case, tube feeding of a participant who was totally blind. The facility environment had a profound influence on the degree to which the staff members could encourage more independence.

A strength of this study was the large number of nursing homes that were included; the 28 nursing homes were all on the lower Eastern Shore of Maryland and Delaware, excluding one state-supported home that had too few elderly residents. Thus, the residents of the participating nursing homes are representative of nursing home residents in a semirural environment. As we described earlier, 40% of the residents had severe cognitive impairments, and no measure of acuity could be ascertained for 18% of the residents (West et al., 2003). Such constraints are particularly challenging when a low vision intervention is considered for an individual.

In summary, low vision rehabilitation in a nursing home facility may have a positive impact if it is properly designed and implemented. Efforts need to be geared to the facility in addition to the residents, and facilities need to educate their staff members on low vision residents and their needs. Low vision optical devices and equipment are a small part of the overall rehabilitation process, which must focus on changing the attitudes of staff members and fostering the independence of residents. Modification of facilities and adaptation are the keys to success with any future rehabilitation intervention program. Special emphasis needs to be placed on illumination, which remains the greatest area of need for residents with low vision and nursing home facilities as a whole. Further research to document the impact of facility-led initiatives, such as changes in lighting and education of staff members, should be a high priority for vision rehabilitation specialists.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a grant from the National Institute on Aging, U.S. National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

James Deremeik, Lions Low Vision Research and Rehabilitation Center, Wilmer Eye Institute, Johns Hopkins Hospital, 550 Building, 6th floor, 600 North Wolfe Street, Baltimore, MD 21287; jderemeik@jhmi.edu..

Aimee T. Broman, Wilmer Eye Institute, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine; aibroman@jhmi.edu..

David Friedman, Wilmer Eye Institute, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine; david.friedman@jhu.edu..

Sheila K. West, Wilmer Eye Institute, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine; shwest@jhmi.edu..

Robert Massof, Lions Low Vision Research and Rehabilitation Center, Wilmer Eye Institute, Johns Hopkins Hospital; rmassof@lions.med.jhu.edu..

William Park, Wilmer Eye Institute, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine; wpark@jhmi.edu..

Karen Bandeen-Roche, Department of Biostatistics, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, 615 North Wolfe Street, Baltimore, MD 21205; kbandeen@jhsph.edu..

Kevin Frick, Department of Health Policy and Management, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, 624 North Broadway, Baltimore, MD 21205; kfrick@jhsph.edu..

Beatriz Muñoz, Wilmer Eye Institute, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine; bmunoz@jhmi.edu..

References

- De Winter LJ, Hoyng CB, Froeling PG, Meulendijks CF, Van der Wilt GJ. Prevalence of remediable disability due to low vision among institutionalized elderly people. Gerontology. 2004;50:96–101. doi: 10.1159/000075560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eye Diseases Prevalence Group Causes and prevalence of visual impairment among adults in the United States. Archives of Ophthalmology. 2004;122:477–485. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.4.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman DS, Muñoz B, Massof RW, Bandeen-Roche K, West SK. Grating visual acuity using the preferential-looking method in elderly nursing home residents. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2002;43:2572–2578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman DS, West SK, Muñoz B, Park W, Deremeik J, Massof R, Frick K, Broman A, McGill W, Gilbert D, German P. Racial variations in causes of vision loss in nursing homes: The Salisbury Eye Evaluation in Nursing Home Groups (SEEING) Study. Archives of Ophthalmology. 2004;122:1019–1024. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.7.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- German PS, Rovner BW, Burton LC, Brant LJ, Clark R. The role of mental morbidity in the nursing home experience. The Gerontologist. 1992;32:152–158. doi: 10.1093/geront/32.2.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz A. Vision impairment and functional disability among nursing home residents. The Gerontologist. 1994;34:316–323. doi: 10.1093/geront/34.3.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illuminating Engineering Society of North America . Lighting and the visual environment for senior living (RP-28-98) Author; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrics. 1986;73:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Marx MS, Werner P, Cohen-Mansfield J, Feldman R. The relationship between low vision and performance of activities of daily living in nursing home residents. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1992;40:1018–1020. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb04479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massof RW. A model of the prevalence and incidence of low vision and blindness among adults in the U.S. Optometry and Vision Science. 2002;79:31–38. doi: 10.1097/00006324-200201000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell P, Hayes P, Wang JJ. Visual impairment in nursing home residents: The Blue Mountains Eye Study. Medical Journal of Australia. 1997;166:73–76. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1997.tb138724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health [October 11, 2007];Healthy people 2010. 2000 from http://www.healthypeople.gov/Document/tableofcontents.htm#Volume2.

- Rubin GS, Roche KB, Prasada-Rao P, Fried LP. Visual impairment and disability in older adults. Optometry and Vision Science. 1994;71:750–760. doi: 10.1097/00006324-199412000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson GR. Low vision in the geriatric population: Rehabilitation and management. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2001;49:317–330. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.4930317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West SK, Friedman D, Muñoz B, Roche KB, Park W, Deremeik J, Massof R, Frick KD, Broman A, McGill W, Gil-bert D, German P. A randomized trial of visual impairment interventions for nursing home residents: Study design, baseline characteristics and visual loss. Ophthalmic Epidemiology. 2003;10:193–209. doi: 10.1076/opep.10.3.193.15081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]