Abstract

Objective To determine if a low glycaemic index diet in pregnancy could reduce the incidence of macrosomia in an at risk group.

Design Randomised controlled trial.

Setting Maternity hospital in Dublin, Ireland.

Participants 800 women without diabetes, all in their second pregnancy between January 2007 to January 2011, having previously delivered an infant weighing greater than 4 kg.

Intervention Women were randomised to receive no dietary intervention or start on a low glycaemic index diet from early pregnancy.

Main outcomes The primary outcome measure was difference in birth weight. The secondary outcome measure was difference in gestational weight gain.

Results No significant difference was seen between the two groups in absolute birth weight, birthweight centile, or ponderal index. Significantly less gestational weight gain occurred in women in the intervention arm (12.2 v 13.7 kg; mean difference −1.3, 95% confidence interval −2.4 to −0.2; P=0.01). The rate of glucose intolerance was also lower in the intervention arm: 21% (67/320) compared with 28% (100/352) of controls had a fasting glucose of 5.1 mmol/L or greater or a 1 hour glucose challenge test result of greater than 7.8 mmol/L (P=0.02).

Conclusion A low glycaemic index diet in pregnancy did not reduce the incidence of large for gestational age infants in a group at risk of fetal macrosomia. It did, however, have a significant positive effect on gestational weight gain and maternal glucose intolerance.

Trial registration Current Controlled Trials ISRCTN54392969.

Introduction

Large for gestational age or macrosomic infants are predisposed to a variety of adverse obstetric and neonatal outcomes, and delivery of a large infant significantly increases the risk of birth complications for the mother.1 2 In the long term, infants at the highest end of the distribution for weight or body mass index are more likely to be obese in childhood, adolescence, and early adulthood than are other infants,3 and they are at greater risk of cardiovascular and metabolic complications later in life.4 5

Several factors influence birth weight, including maternal age, parity, ethnicity, and previous delivery of a large for gestational age infant.6 Both maternal weight and gestational weight gain exert a significant influence on birth weight.7 8 9 Increased maternal body mass index confers an elevated risk of delivering a heavier infant,10 and evidence supports a strong associations between excessive weight gain and an increased birth weight.11 12

Glucose is the main energy substrate for fetal growth.13 Birth weights in infants of mothers with diabetes are increased; up to 35% are above the 95th centile.14 Moreover, a strong, continuous association has been shown between maternal glucose concentrations below those diagnostic of diabetes and the incidence of macrosomia and its inherent complications.15 Maternal diet, and particularly the type and content of carbohydrate, influences maternal blood glucose concentrations. However, different carbohydrate foods produce different glycaemic responses. Jenkins developed the glycaemic index in 1981 as a method for assessing the glycaemic responses to different carbohydrates.16 A low glycaemic index diet has been shown to blunt the increase in insulin resistance in mid and late pregnancy typically seen in westernised societies.17 Eating primarily high glycaemic carbohydrate foods is postulated to result in feto-placental overgrowth and excessive maternal weight gain and to lead to a predisposition to fetal macrosomia, whereas intake of low glycaemic carbohydrates predisposes to normal infant birth weight and normal maternal weight gain.13 18 To date, the effect of introducing a low glycaemic index diet in pregnancy to reduce the incidence of fetal macrosomia has not been subject to a randomised controlled trial.

Fetal macrosomia recurs in a second pregnancy in 30-50% of cases, and gestational weight gain influences this risk.19 20 Our objective was to do a randomised controlled trial of a low glycaemic index diet from early pregnancy in a group of women all in their second pregnancies (secundigravid) who had previously delivered an infant weighing greater than 4000 g (ROLO study). Our hypothesis was that a low glycaemic index diet would reduce the recurrence of fetal macrosomia. The primary outcome measure was difference in birth weight between the intervention and control groups, and the secondary outcome was difference in gestational weight gain.21

Methods

This was a randomised control trial with institutional ethical approval and maternal written consent carried out at the National Maternity Hospital, Dublin, Ireland.

Patient selection

All secundigravid women who had previously delivered a macrosomic infant weighing greater than 4 kg were identified on first contact with the hospital and recruited at first antenatal consultation. At this visit, women with any underlying medical disorders, including a previous history of gestational diabetes, those on any drugs, and those unable to give full informed consent were excluded. Other exclusion criteria were age less than 18 years, gestation greater than 18 weeks, and multiple pregnancy.

After giving written informed consent, recruited patients were randomised into either the control or the intervention arm of the study. The research midwife did the randomisation by using computer generated allocations in a ratio of one to one contained in sealed opaque envelopes.

Dietary intervention

Women in the control arm received routine antenatal care. As is standard practice at our institution, this did not involve any formal dietary advice or specific advice about gestational weight gain. Women randomised to the intervention group attended one dietary education session lasting two hours in groups of two to six women with the research dietitian. The mean gestational age of those attending the dietary session was 15.7 (SD 3.0) weeks. The diet was designed to meet current recommendations for pregnant women.22 Women were first advised on general healthy eating guidelines for pregnancy, following the food pyramid. The remainder of the education session focused on the glycaemic index—its definition, concept, and rationale for use in pregnancy. Women were encouraged to choose as many low glycaemic index foods as possible and to exchange high glycaemic index carbohydrates for low glycaemic index alternatives. Women received written resources about low glycaemic index foods after the education session (web appendix). The recommended low glycaemic index diet was eucaloric, and women were not advised to reduce their total caloric intake. The research dietitian met with the patients at 28 and 34 weeks’ gestation for reinforcement of the low glycaemic index diet and to answer any dietary queries they had.

Data collection and trial management

At their first antenatal consultation, all patients had their weight and height recorded and their body mass index calculated. Fasting blood glucose was measured and a mid upper arm circumference recorded. Additional demographic data including smoking history and socioeconomic data were also recorded. Maternal weight was recorded at each antenatal consultation.

At 28 weeks’ gestation, repeat fasting blood glucose was measured and glucose challenge testing one hour after a 50 g glucose load was carried out. In accordance with the institutional policy, women with a glucose challenge test result of 8.3 mmol/L or greater had formal glucose tolerance testing carried out to rule out gestational diabetes. Gestational diabetes was diagnosed when an abnormal glucose challenge test was followed by two or more abnormal values on a three hour 100 g glucose tolerance test using the Carpenter and Coustan criteria.23 When gestational diabetes was diagnosed, care continued in the multidisciplinary diabetic clinic.

We assessed fetal biometry ultrasonographically at 34 weeks’ gestation. This included a measurement of fetal anterior abdominal wall width. This measurement has been used in populations both with and without diabetes as a marker of fetal adiposity.24 25 One of two blinded sonographers made ultrasound measurements by using a Voluson 730 Expert (GE Medical Systems, Germany).

At delivery, we recorded infants’ birth weight, length, and head circumference and calculated the ponderal index (100 × mass in g/height in cm3). We used Gestation Network’s Bulk Calculator version 6.2.3 UK to calculate birthweight centiles corrected for maternal weight, height, parity, ethnicity, gestational age at delivery, and infant’s sex.26

The trial steering committee met bimonthly. An independent data monitoring committee reviewed recruitment and safety data after 350 patients had been recruited.

Dietary assessment

All women completed three food diaries of three days each—one before dietary intervention and one each in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy. These collected information on typical meal pattern and food choices over three days and allowed for estimation of the glycaemic index. We calculated the glycaemic load as the mathematical product of the glycaemic index of a food and its carbohydrate content in grams divided by 100 (glycaemic load=glycaemic index/100 × amount of available carbohydrate). To assess adherence to the low glycaemic index diet, we gave patients in the intervention group a questionnaire at their 34 week antenatal visit. This was based on a five point Likert-type scale (1=“I followed the recommended diet all of the time”; 5=“I followed the recommended diet none of the time”).

Sample size

A sample size calculation based on a significance level set at 5% and power set at 90% indicated that we needed 360 patients in each group to detect a 0.25 standard deviation difference in birth weight between the two groups, equivalent to a 102 g difference in the birth weight.

Statistical analysis

We did the primary analysis with an independent samples t test with birth weight as the primary outcome. We used the independent samples t test for comparison of means within groups of patients. We used χ2 tests to compare categorical variables between groups. We set statistical significance at P<0.05. We investigated weight gain both in an independent samples t test on amount of weight gained and on the basis of a linear model examining total weight with control for starting weight. All reported P values are two sided. We used SPSS for Windows version 18.0 for statistical analysis.

Results

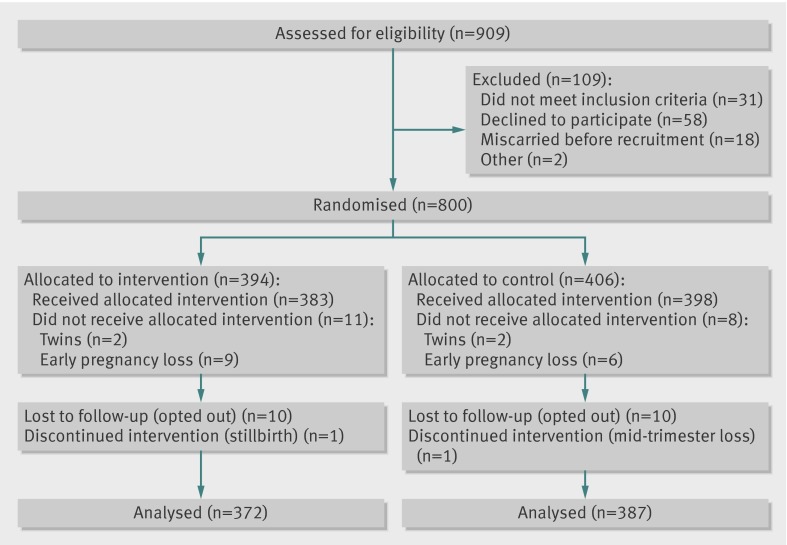

The study period was from January 2007 to January 2011, and the final women delivered in August 2011. During the study period, 909 women in their second pregnancies who met inclusion criteria having previously delivered an infant weighing greater than 4000 g were contacted by telephone and informed of the study. Of these, 851 agreed to meet with a researcher. A further 51 women met exclusion criteria or miscarried before randomisation, and 800 were recruited and randomised (figure). One stillbirth occurred in the intervention arm (an infant at 39 weeks’ gestation weighing 2.9 kg; postmortem examination confirmed trisomy 21). Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics; we noted no differences between the two groups.

Flow diagram of study recruitment and follow-up. Early pregnancy loss=miscarriage/termination at <14 weeks’ gestation; mid-trimester loss=loss at >14 but <24 weeks’ gestation; stillbirth=fetal demise at >24 weeks’ gestation

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics at recruitment of control and intervention groups. Values are mean (SD) unless stated otherwise

| Baseline characteristic | Intervention group (n=383) | Control group (n=398) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 32.0 (4.2) | 32.0 (4.2) |

| Gestational age at recruitment (weeks) | 13.0 (2.3) | 12.9 (2.2) |

| Weight (kg) | 73.8 (14.8) | 73.4 (13.7) |

| Height (cm) | 166.3 (6.4) | 168.9 (6.5) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 26.8 (5.1) | 26.8 (4.8) |

| Mid upper arm circumference (cm) | 29.5 (3.6) | 29.5 (3.4) |

| Fasting glucose (mmol/L) | 4.5 (0.36) | 4.5 (0.38) |

| Previous birth weight (g) | 4253 (261) | 4242 (236) |

| No (%) smokers | 17 (4) | 12 (3) |

Primary outcome

We found no significant difference between the two groups in birth weight at delivery. Similarly, we found no difference in mean birthweight centile, birth weight adjusted for maternal body mass index, gestation at delivery, infant’s sex, or ponderal index at birth between the two groups (table 2). Fetal macrosomia (birth weight >4000 g) recurred in 189 (51%) of the intervention group and 199 (51%) of the control group (P>0.05).

Table 2.

Comparison of infant, fetal, and maternal outcomes between intervention and control groups. Values are mean (SD) unless stated otherwise

| Outcome | Intervention group (n=372) | Control group (n=387) | Mean difference (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birth weight (g) | 4034 (510) | 4006 (497) | 28.6 (−45.6 to 102.8) | 0.449 |

| Birthweight centile | 70.5 (25.6) | 72.8 (25.6) | −1.6 (−5.39 to 2.2) | 0.409 |

| No (%) birth weight >4000 g | 189 (51) | 199 (51) | — | 0.88 |

| Length at birth (cm) | 52.9 (2.7) | 52.6 (2.1) | 0.263 (−0.13 to 0.655) | 0.189 |

| Head circumference at birth (cm) | 35.8 (1.3) | 35.7 (1.5) | −0.00225 (−0.231 to 0.227) | 0.985 |

| Ponderal index at birth | 2.76 (3.8) | 2.75 (0.33) | 0.011 (−0.36 to 0.39) | 0.95 |

| Birthweight difference* from first pregnancy (g) | −214.2 (541) | −250.8 (512) | −36.6 (−120.15 to 46.95) | 0.507 |

| Estimated fetal weight at 34 weeks (g) | 2631 (326) | 2616 (368) | 14.74 (−40.89 to 70.38) | 0.603 |

| Fetal abdominal circumference at 34 weeks (mm) | 315.8 (16.7) | 315.6 (19.2) | −0.201 (−3.067 to 2.665) | 0.89 |

| Fetal anterior abdominal wall width at 34 weeks (mm) | 5.0 (1.3) | 5.1 (1.2) | −0.108 (−0.323 to 0.107) | 0.323 |

| Fasting glucose at 28 weeks (mmol/L) | 4.45 (0.4) | 4.51 (0.6) | −0.058 (−0.146 to 0.03) | 0.198 |

| Glucose challenge test at 28 weeks (mmol/L) | 6.47 (1.4) | 6.67 (1.7) | −0.205 (−0.44 to 0.031) | 0.088 |

| Cord blood glucose (mmol/L) | 4.17 (1.1) | 4.16 (1.2) | 0.014 (−0.19 to 0.217) | 0.896 |

| Weight gain at 24 weeks (kg) | 5.3 (2.7) | 5.5 (2.7) | −0.244 (−0.786 to 0.299) | 0.378 |

| Weight gain at 28 weeks (kg) | 7.1 (2.8) | 7.7 (3.0) | −0.593 (−1.072 to −0.114) | 0.015 |

| Weight gain at 34 weeks (kg) | 10.1 (3.7) | 10.9 (3.9) | −0.83 (−1.48 to −0.182) | 0.012 |

| Weight gain at 40 weeks (kg) | 12.2 (4.4) | 13.7 (4.9) | −1.346 (−2.451 to −0.241) | 0.017 |

*Birth weight in second pregnancy minus birth weight in first pregnancy.

Secondary outcome

We found a significant difference in the secondary outcome between women in the intervention and control arms of the study. Women who received dietary intervention had significantly less gestational weight gain than did those who received no dietary intervention. At 40 weeks’ gestation, the mean gestational weight gain in the intervention group was 12.2 kg compared with 13.7 kg in the control group (mean difference −1.3, 95% confidence interval −2.4 to −0.2; P=0.01) (table 2). The difference between the two groups persisted when we controlled for initial weight with regression analysis (mean difference −0.7, −1.3 to −0.13; P=0.018).

Women in the intervention arm of the study were significantly less likely to exceed gestational weight gain recommendations as outlined by the Institute of Medicine (139/368 (38%) v 182/380 (48%); P=0.01).27 Among women with a normal body mass index (18.5-24.9), 40/155 (26%) controls exceeded the guidelines compared with 25/162 (15%) of the intervention arm (P=0.02). In overweight women (body mass index 25-29.9), 99/148 (67%) controls and 74/139 (53%) of those receiving the dietary intervention exceeded the guidelines (P=0.02). We found no significant difference between the two groups in the proportion of women with a body mass index of greater than 30.0 who exceeded gestational weight gain guidelines (43/75 (57%) v 40/67 (60%); P=0.8).

Overall, a significantly higher proportion of women in the control group had a glucose challenge test result of greater than 7.8 mmol/L at 28 weeks’ gestation. Similarly, a higher proportion of women in the control arm than in the intervention had either a fasting glucose at 28 weeks of 5.1 mmol/L or greater or a glucose challenge test of greater than 7.8 mmol/L. An equal number of women in each arm had formal glucose tolerance testing, and no significant difference existed in the incidence of gestational diabetes according to either Carpenter and Coustan criteria (7 v 9) or the American Diabetes Association criteria (12 v 18).23 28 Cord blood glucose was similar between the two groups (table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of maternal glucose concentrations at 28 weeks’ gestation in intervention and control groups. Values are numbers (percentages)

| Measurement | Intervention group | Control group |

|---|---|---|

| 28 week fasting glucose ≥5.1 mmol/L | 24/321 (7) | 41/352 (12) |

| GCT >7.8 mmol/L | 54/350 (15) | 79/371 (21)* |

| 28 week fasting glucose ≥5.1 mmol/L or GCT >7.8 mmol/L | 67/320 (21) | 100/352 (28)* |

| GCT >8.3 mmol/L | 42/350 (12) | 52/371 (14) |

| Gestational diabetes (Carpenter and Coustan criteria)22 | 7/350 (2) | 9/371 (2) |

| Gestational diabetes (American Diabetes Association criteria)27 | 12/350 (3) | 18/371 (5) |

GCT=glucose challenge test (serum glucose measured 1 hour after 50 g glucose load).

*Two tailed P<0.05.

Dietary assessment

We found no difference in the dietary glycaemic index between women in the intervention group and controls before the intervention (57.3 (SD 4.2) v 57.7 (4.0); mean difference −0.4, −0.9 to 0.18; P=0.17). After introduction of the low glycaemic index diet, the intervention group had a lower glycaemic index in the second trimester (56.1 (4.0) v 57.8 (3.7); mean difference −1.7, −2.2 to −1.15; P<0.001) and third trimester (56.0 (3.8) v 57.7 (3.9); −1.7, −2.2 to −1.1; P<0.001). Similarly, we found no significant difference between the two groups in mean glycaemic load at randomisation (132.7 (32.9) v 136.4 (38.7); mean difference −3.7, −8.8 to 1.4; P=0.15). After introduction of the low glycaemic index diet, the intervention group had a significantly lower glycaemic load in the second trimester (124.1 (32.5) v 140.0 (36.3); mean difference −15.9, −20.8 to −10.9; P<0.001) and third trimester (127.1 (30.4) v 139.9 (37.5); −12.8, −17.6 to −7.9; P<0.001). No difference existed between the two groups in energy intake at baseline. After randomisation, women in the intervention group had significantly lower energy intake in the second trimester (7.6 (1.9) v 8.1 (2.0) MJ; mean difference −0.5, −0.77 to −0.22; P<0.01) and third trimester (7.6 (1.9) v 8.1 (2.0) MJ; −0.5, −0.77 to −0.22; P<0.01). They also had significantly higher intakes of fibre in the third trimester. Almost 80% (n=294) of the intervention arm reported following the low glycaemic index dietary advice either all or most of the time on the adherence questionnaire.

Maternal outcomes

We found no significant difference in the rate of caesarean delivery between the two groups, although women in the intervention arm of the study delivered at a later gestational age than did those in the intervention arm. (280.8 (10.3) v 282.5 (9.2) days; mean difference 1.7, 0.3 to 3.1; P=0.017). Women in the intervention arm were more likely to have their labour induced than were controls (65 (18%) v 41 (11%); P=0.012). Four women in the intervention arm had a primary postpartum haemorrhage of greater than 500 mL, compared with five in the control group. We found no difference in the incidence of anal sphincter injury between the two groups—four occurred in the intervention group and five in the control group. In both groups, women delivered at an earlier gestational age compared with their first pregnancies (281.1 (10.1) v 286.9 (6.6) days; mean difference −5.8, −7.03 to −4.6).

Fetal outcomes

In total, 11 preterm deliveries at less than 37 weeks occurred—three in the intervention arm and eight in the controls (P>0.05). Of these, just three were at less than 34 weeks’ gestation—one at 28 weeks in the intervention arm and two at 28 and 33 weeks’ gestation in the controls. Six cases of shoulder dystocia occurred in total—two in the intervention group and four in the controls (P>0.05).

Discussion

We have found that a low glycaemic index diet in pregnancy had no effect on infants’ birth weight in a group at risk of fetal macrosomia. It did, however, have a significant positive effect on gestational weight gain and on maternal glucose intolerance.

Comparison with existing literature

In recent years, interest has been increasing in the role of the glycaemic index in pregnancy, and in particular its potential to modulate fetal growth.29 30 31 Until now, the small number of intervention trials that have examined the use of a low glycaemic index diet in pregnancy suggested that it might be useful in preventing fetal macrosomia. The earliest publication by Clapp et al in 1997 included just 12 women but found that those on a low glycaemic index diet during pregnancy not only had lower gestational weight gains but also gave birth to infants with lower birth weights than did those on a high glycaemic index diet.13 Moses et al in 2006 reported a study of 70 women who were assigned to receive dietary counselling that encouraged low glycaemic index carbohydrate foods or high fibre, moderate to high glycaemic index foods.18 They found a significantly higher prevalence of large for gestational age infants in those on the high glycaemic index diet of 33% compared with just 3% in those on the low glycaemic index diet. More recently, Rhodes et al reported the results of a pilot study comparing a low glycaemic load diet with a low fat diet in a group of 46 overweight and obese pregnant women. They used a much more intensive regimen, including weekly reinforcement and home food delivery. Their results in this particular patient group are very interesting and reflect our experience of little or no effect on birth weight but an improvement in maternal outcomes.32

Strengths, limitations, and clinical implications

The ROLO study is a sufficiently powered, randomised controlled study, and we found no significant difference in absolute birth weight, birthweight centile, or incidence of macrosomia. We did find that a low glycaemic index diet in pregnancy significantly reduced gestational weight gain, our secondary outcome. By 40 weeks’ gestation, women in the diet arm had gained 1.5 kg less than had those women who received no dietary intervention. A significant proportion of women in each arm of the study exceeded gestational weight gain guidelines as outlined by the Institute of Medicine.27 Overall, 48% of women in our control group exceeded these guidelines, which is comparable to the 47.5% recently reported in a large low risk cohort of almost 8000 women.33 Women who received the low glycaemic index diet, however, were significantly less likely to exceed these gestational weight gain guidelines; just 38% did so. Maternal weight gain during pregnancy has been independently linked to adverse obstetric outcomes.11 34 Excessive gestational weight gain also has potential maternal implications, such as an increased operative delivery rate,2 a higher likelihood of postpartum weight retention,34 and a predisposition to later obesity.35 36 37

Additionally, we found that a low glycaemic index diet in pregnancy reduced the incidence of maternal glucose intolerance at 28 weeks’ gestation. A significantly higher proportion of women in the control arm had either a fasting glucose concentration of 5.1 mmol/L or greater or a glucose challenge test result of greater than 7.8 mmol/L at 28 weeks. Despite this reduction, we saw no difference between the two groups in the incidence of gestational diabetes. Since the publication of the HAPO study in 2008,15 however, a clear association between glucose concentrations below those diagnostic of gestational diabetes and several adverse outcomes of pregnancy is widely accepted.38 39 In line with our institutional policy on screening for gestational diabetes, we did not do formal glucose tolerance testing on all women; this may have limited the number of cases of gestational diabetes diagnosed.

Our study has some limitations worthy of consideration. Our patients were all secundigravid and did not have diabetes. We specifically excluded those with a previous history of gestational diabetes, as at our institution this group are routinely started on a low glycaemic index diet in subsequent pregnancies from the first trimester. Our study mothers were specifically selected to allow us examine the effect of a low glycaemic index diet among healthy euglycaemic women. Our selection criteria may have introduced a degree of selection bias towards women who were giving birth to larger babies owing to genetic potential rather than to aberrations in maternal metabolism. Birth weight is a complex interplay of genetic and environmental factors. The proportion of infants weighing greater than 4000 g who are larger than expected owing to excess glucose transfer across the placenta as detected by fetal cord hyperinsulinaemia may be as low as 15-20%.40 Our strict inclusion criteria might explain why the differences we observed in maternal outcomes did not translate into a difference in infant birth weight.

As expected, our results may also have been subject to the limitations of the Hawthorne effect.41 A blinded randomised trial of dietary intervention is not possible. All women recruited to the study were aware that they were selected because of the birth weight of their first child, and they may have been motivated to reduce the risk of delivering an infant of similar size in their second pregnancy. We imposed no limitations to women in the control arm introducing some element of dietary modifications themselves, which may have altered the outcome. Nonetheless, the finding of a significant difference between the two groups in terms of gestational weight gain and glucose intolerance would suggest that any potential Hawthorne effect was small.

Importantly, we identified no adverse outcomes associated with the use of a low glycaemic index diet in pregnancy. Potential benefits were seen, particularly in terms of limiting maternal gestational weight gain to within Institute of Medicine guidelines and an improvement in maternal glucose homoeostasis. These findings were identified after a single formal small group dietetic session in early pregnancy. This suggests that this type of simple dietary intervention is adequate in improving maternal nutrition.

Conclusions

With more than one billion adults in the world now overweight and more than 600 million clinically obese,42 effective strategies to combat the incidence of fetal macrosomia as a significant precursor of childhood obesity are needed. Although a low glycaemic index diet alone may not be sufficient to combat the problem, it does offer significant maternal benefits. The use of a low glycaemic index diet in pregnancy is a simple, safe, and effective measure to improve maternal glucose homoeostasis and to reduce gestational weight gain.

What is already known on this topic

Fetal macrosomia is associated with significant maternal and neonatal morbidity and confers an elevated risk of childhood obesity

Maternal weight, gestational weight gain, and maternal glucose homoeostasis all exert a significant influence on birth weight

A low glycaemic diet blunts the mid and late pregnancy increase in insulin resistance and may predispose to normal infant birth weight and normal maternal weight gain

What this study adds

A low glycaemic index diet in pregnancy had no effect on infants’ birth weight in a group at risk of fetal macrosomia

It did, however, have a significant positive effect on gestational weight gain and on maternal glucose intolerance

We thank the staff at the National Maternity Hospital; Jacinta Byrne, research midwife; Helen Colhoun, epidemiologist; Tim Grant, biostatistical consultant at C-Star, University College Dublin; and the mothers who participated in the study.

Contributors: FMMcA conceived and designed the study. RM and MEF contributed to the study design and manuscript preparation. CAMcG carried out the intervention and contributed to manuscript preparation. JMW did the analysis and wrote the manuscript. All of the authors reviewed and revised the final version of the manuscript. FMMcA is the guarantor.

Funding: This trial was funded by the Health Research Board of Ireland, with additional financial support from the National Maternity Hospital Medical Fund. None of the funding sources had a role in the trial design or manuscript preparation.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work (apart from the Health Research Board of Ireland and the National Maternity Hospital Medical Fund); no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: This study received approval from the Ethics Committee of the National Maternity Hospital in June 2006; all participants gave written consent.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2012;345:e5605

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

References

- 1.Boulet SL, Alexander GR, Salihu HM, Pass M. Macrosomic births in the United States: determinants, outcomes, and proposed grades of risk. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003;188:1372-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gregory KD, Henry OA, Ramicone E, Chan LS, Platt LD. Maternal and infant complications in high and normal weight infants by method of delivery. Obstet Gynecol 1998;92:507-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boney CM, Verma A, Tucker R, Vohr BR. Metabolic syndrome in childhood: association with birth weight, maternal obesity, and gestational diabetes mellitus. Pediatrics 2005;115:e290-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hermann GM, Dallas LM, Haskell SE, Roghair RD. Neonatal macrosomia is an independent risk factor for adult metabolic syndrome. Neonatology 2010;98:238-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ornoy A. Prenatal origin of obesity and their complications: gestational diabetes, maternal overweight and the paradoxical effects of fetal growth restriction and macrosomia. Reprod Toxicol 2011;32:205-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walsh JM, McAuliffe FM. Prediction and prevention of the macrosomic fetus. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2012;162:125-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abrams BF, Laros RK Jr. Prepregnancy weight, weight gain, and birth weight. Am J Obstet Gynaecol 1986;154:503-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frentzen BH, Dimperio DL, Cruz AC. Maternal weight gain: effect on infant birth weight among overweight and average-weight low-income women. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1988;159:1114-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson JW, Longmate JA, Frentzen B. Excessive maternal weight and pregnancy outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1992;167:353-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seidman DS, Ever-Hadani P, Gale R. The effect of maternal weight gain in pregnancy on birth weight. Obstet Gynecol 1989;74:240-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siega-Riz AM, Viswanathan M, Moos MK, Deierlein A, Mumford S, Knaack J, et al. A systematic review of outcomes of maternal weight gain according to the Institute of Medicine recommendations: birthweight, fetal growth, and postpartum weight retention. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009;201:339.e1-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walsh JM, Murphy DJ. Weight and pregnancy. BMJ 2007;335:169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clapp JF 3rd. Maternal carbohydrate intake and pregnancy outcome. Proc Nutr Soc 2002;61:45-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hawthorne G, Robson S, Ryall EA, Sen D, Roberts SH, Ward Platt MP. Prospective population based survey of outcome of pregnancy in diabetic women: results of the Northern Diabetic Pregnancy Audit, 1994. BMJ 1997;315:279-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.HAPO Study Cooperative Research Group. Hyperglycemia and adverse pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med 2008;358:1991-2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jenkins DJ, Wolever TM, Taylor RH, Barker H, Fielden H, Baldwin JM, et al. Glycaemic index of foods: a physiological basis for carbohydrate exchange. Am J Clin Nutr 1981;34:362-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fraser RB, Ford FA, Lawrence GF. Insulin sensitivity in third trimester pregnancy: a randomised study of dietary effects. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1988;95:223-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moses RG, Luebcke M, Davis WS, Coleman KJ, Tapsell LC, Petocz P, et al. Effect of a low-glycaemic-index diet during pregnancy on obstetric outcomes. Am J Clin Nutr 2006;84:807-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mahony R, Walsh C, Foley ME, Daly L, O’Herlihy C. Outcome of second delivery after prior macrosomic infant in women with normal glucose tolerance. Obstet Gynecol 2006;107:857-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mahony R, Foley M, McAuliffe F, O’Herlihy C. Maternal weight characteristics influence recurrence of fetal macrosomia in women with normal glucose tolerance. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2007;47:399-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walsh J, Mahony R, Foley M, McAuliffe F. A randomised control trial of low glycaemic index carbohydrate diet versus no dietary intervention in the prevention of recurrence of macrosomia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2010;10:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Taskforce on Obesity. Obesity: the policy challenges. Department of Health, 2005.

- 23.Coustan DR, Carpenter MW. The diagnosis of gestational diabetes. Diabetes Care 1998;21(suppl 2):B5-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Higgins MF, Russell NM, Mulcahy CH, Coffey M, Foley ME, McAuliffe FM. Fetal anterior abdominal wall thickness in diabetic pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2008;140:43-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petrikovsky BM, Oleschuk C, Lesser M, Gelertner N, Gross B. Prediction of fetal macrosomia using sonographically measured abdominal subcutaneous tissue thickness. J Clin Ultrasound 1997;25:378-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gestation Network. GROW customised centile calculators. 2007 www.gestation.net/birthweight_centiles/birthweight_centiles.htm.

- 27.Rasmussen KM, Yaktine AL, eds. Weight gain during pregnancy: re-examining the guidelines. National Academies Press, 2009. [PubMed]

- 28.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2011. Diabetes Care 2011;34(suppl 1):S11-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Louie JC, Brand-Miller JC, Markovic TP, Ross GP, Moses RG. Glycaemic index and pregnancy: a systematic literature review. J Nutr Metab 2010;2010:282464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McGowan CA, McAuliffe FM. The influence of maternal glycaemia and dietary glycaemic index on pregnancy outcome in healthy mothers. Br J Nutr 2010;104:153-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moses RG, Barker M, Winter M, Petocz P, Brand-Miller JC. Can a low-glycaemic index diet reduce the need for insulin in gestational diabetes mellitus? A randomised trial. Diabetes Care 2009;32:996-1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rhodes ET, Pawlak DB, Takoudes TC, Ebbeling CB, Feldman HA, Lovesky MM, et al. Effects of a low-glycemic load diet in overweight and obese pregnant women: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2010;92:1306-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carreno CA, Clifton RG, Hauth JC, Myatt L, Roberts JM, Spong CY et al. Excessive early gestational weight gain and risk of gestational diabetes mellitus in nulliparous women. Obstet Gynecol 2012;119:1227-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scholl TO, Hediger ML, Schall JI, Ances IG, Smith WK. Gestational weight gain, pregnancy outcome, and postpartum weight retention. Obstet Gynecol 1995;86:423-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rooney BL, Schauberger CW. Excess pregnancy weight gain and long-term obesity: one decade later. Obstet Gynecol 2002;100:245-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Amorim AR, Rossner S, Neovius M, Lourenco PM, Linne Y. Does excess pregnancy weight gain constitute a major risk for increasing long-term BMI? Obesity 2007;15:1278-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rooney BL, Schauberger CW, Mathiason MA. Impact of perinatal weight change on long-term obesity and obesity-related illnesses. Obstet Gynecol 2005;106:1349-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walsh JM, Mahony R, Byrne J, Foley M, McAuliffe FM. The association of maternal and fetal glucose homeostasis with fetal adiposity and birthweight. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2011;159:338-41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yogev Y, Chen R, Hod M, Coustan D, Oats J, McIntyre B, et al for the Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome (HAPO) Study Cooperative Research Group. Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome (HAPO) study: preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2010;202:255.e1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stanley KP, Fraser RB, Milner M, Bruce C. Cord insulin and C-peptide—distribution in an unselected population. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1992;99:512-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roethlis-Berger FJ, Dickinson WJ. Management and the worker: an account of a research programme conducted by the Western Electric Company, Hawthorne Works, Chicago. Harvard University Press, 1939.

- 42.World Health Organization. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. WHO, 2000. [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.