Abstract

Background

Past studies have examined the relationship of lung cancer to smoking using longitudinal data for select samples. This study applies the two-stage clonal expansion model to U.S. +smoking data over a 25 year period.

Methods

Smoking Base Case (SBC) data on actual smoking duration and intensity from the years 1975–2000 are applied by gender to separate TSCE models, which are then calibrated to historical trends in lung cancer death rates using regression analysis. The uncalibrated and calibrated TSCE models are also applied to SBC data for two scenarios: 1) no tobacco control and 2) complete tobacco control. The results are used to develop estimates of the number of lives saved as a result of tobacco control and how many lives would be saved if cigarette use had ceased in 1965.

Results

Predictions of lung cancer from the TSCE models with CPS-II and especially the CPS-I data for males and especially females are considerably below historical rates with the deviations from historical rates increasing over time. Residual trends unrelated to the smoking models were also found. Tobacco control activities saved approximately 625,000 lives between the years 1975 and 2000. An additional 2,110,000 lives would have been saved if all smoking was stopped in 1965.

Conclusions

Tobacco control has successfully prevented lung cancer deaths, but many more lives could be saved with further reductions in smoking rates. Systematic biases were observed from TSCE models using CPS-I and CPS-II data to estimate smoking-related lung cancer deaths.

Keywords: lung cancer, simulation, macromodel

1. INTRODUCTION

Trends in U.S. lung cancer death rates have dramatically changed in the last twenty years 1. After a long upward climb, the age-adjusted lung cancer mortality rate for men has been declining steadily since 1984 and for women began to level off in the 1990s. The reversal in trends has generally been attributed to reduced smoking.2 Smoking has been established as the leading cause of lung cancer deaths, with as much as 90% of the deaths due to smoking.3, 4 The relationship of lung cancer to smoking has been established by biological and epidemiological studies 3. At a population level, lung cancer has been strongly linked to the smoking dose, both in terms of the number of cigarettes smoked per day and the number of years smoked.5–10

Estimates of lung cancer deaths due to smoking for the U.S.3, 11 are usually based on relative risks estimated from the CPS-II data. Nevertheless, this data is not representative of the U.S. population, because it over-represents those who are middle class, married, White, and more educated.12, 13 In addition, there may be bias from misclassification error, due to former or current smokers classifying themselves as never smokers, exposure of true never smokers to second hand smoke and undetected lung cancer.14–17 Risks also appear to be changing over time. Comparing the CPS-I (1959–1981) to the CPS-II (1982–1988), the relative risk of lung cancer in smokers increased from 11.9 to 23.2 for men and from 2.7 to 12.8 for women.18 While much of the change can be explained by the changes in smoking behaviors, such as duration and intensity, a large portion of the difference is still unexplained.18, 19

This study examines the role of smoking in explaining levels and trends in lung cancer deaths. We employ a macro modeling approach that uses smoking prevalence, duration and intensity data and lung cancer data by age, year and gender. We first apply this data, known as the smoking base case (SBC), to the two stage clonal expansion (TSCE) model to incorporate the role of smoking in predicting lung cancer deaths. We aggregated the predictions from the TSCE over age groups for each year and gender and compare the results to levels and trends in historical lung cancer deaths by gender over the years 1995 through 2000. We develop separate predictions using the CPS-I and CPS-II versions of the TSCE models. By separately considering models that use CPS-I and CPS-II data, we also indirectly consider how well these two data sets, as applied to the TSCE model, explain lung cancer deaths. Unlike other studies in this supplement, we focus on annual trends using a population level “top down” approach rather than an individual level “bottom up” approach, with the aim of examining how predicted trends in lung cancer deaths using CPS data deviate from actual trends.

This paper also considers the role of tobacco control efforts in reducing lung cancer deaths. Beginning with the Surgeon General’s Report in 1964, efforts have been aimed at reducing smoking; restrictions have been placed on certain types of advertising and on smoking in public places, and higher taxes have been imposed on cigarettes. Using SBC data, we consider the counterfactual cases of how lung cancer rates would have been affected 1) in the absence of tobacco control policies since the early fifties, and 2) if all cigarette use (i.e., all smokers permanently quit and no new initiation takes place) was terminated in 1965.

2. METHODS

This study considers male and female lung cancer rates, confining the analysis to ages 30 to 84 and to the years 1975 to 2000. Lung cancer deaths by smoking status, age, gender and year are predicted using separate versions of the TSCE model using CPS-I and CPS-II data. Predictions are developed under three scenarios: 1) actual tobacco control (ATC), 2) no tobacco control (NTC), and 3) complete tobacco control (CTC). We then fit the predicted rates under ATC to historical lung cancer deaths to evaluate the predictions of the models and calibrate the models. Finally, we apply the calibrated equations to the NTC and CTC scenarios.

2.a. Data

SBC data on smoking prevalence, smoking intensity and smoking duration were provided for each of the smoking scenarios: ATC, NTC and CTC. Smoking prevalence data were distinguished by 7 smoking categories: never, current, and former smokers, with former smokers further divided into 5 groups based on how long ago they had quit (1–2, 3–5, 6–10, 11–15, and 16+ years). For smokers and former smokers, intensity data were measured as the average number of cigarettes smoked per day. Duration of smoking for smokers was measured as the current age minus the age of smoking initiation, and for former smokers was measured as the current age minus the age of smoking initiation, minus the number of years quit.

SBC data were provided by 5 year cohort, gender and year. We converted the data by cohort, gender and year into age groups by gender and year. To obtain data for a single age, we smoothed over 5 ages starting at age 32 and ending at age 82, and extrapolated estimates for ages 30 and 31 from smoothed estimates for ages 32 and 33, and for ages 83 and 84 from smoothed estimates for ages 81 and 82.

SBC data were also provided on population and historical U.S. lung cancer deaths by age, gender and year for 1975 to 2000, from which we calculated lung cancer deaths per 100,000. Population data were also applied to the smoking prevalence data to obtain the number of never, current and former (by years quit) smokers by age, gender and year.

2.b. Methods used to predict lung cancer death rates by smoking-related factors

To relate smoking duration and intensity to lung cancer death rates, we used the TSCE model as applied by Hazelton et al.10 to the CPS-I and CPS-II data. They estimated a series of non-linear equations that related the lung cancer death rate to rates of initiation, cell division, apoptosis of initiated cells, and malignant conversion of initiated cells, which, in turn, were a function of smoking intensity and duration. Programming for the models was made available to us by the authors as a Microsoft Excel add-in.

Following Hazelton et al.,10 we developed separate estimates of lung cancer death rates for the CPS-I and CPS-II models and separate estimates by gender. Specifically, for each of the three scenarios (ATC, NTC and CTC), four (male CPS-I, female CPS-I, male CPS-II, and female CPS-II) separate sets of estimates of lung cancer death rates were developed, yielding a total of 12 separate cases. Data on smoking intensity and duration (both equal to zero in the case of never smokers) by smoking status (never, current, and 5 categories of former smokers), age and year were loaded into the programmed TSCE model for each of the 12 cases

For each of the 12 cases, death rates were applied by smoking status, age and year to the population in the respective categories to obtain total deaths. The deaths were summed over the 7 smoking status categories and age for each of the 12 cases to obtain predicted total lung cancer deaths by age and year, which were then converted to lung cancer death rates.

In addition to considering lung cancer death rates for the 30 to 84 year old age group, we considered selected age sub-groups. Based on a visual inspection of historical rates by 5 year age groups, we grouped together ages 30 to 49, 50 to 69, and 70 to 84 because of the similar trend patterns observed within those groups. We also considered rates distinguished by smoking status.

2.c. Calibration and Comparison of Predicted to Historical Rates

The TSCE models were originally estimated using either CPS-I or CPS-II data, neither of which are representative of the U.S. population and may be subject to misclassification error. Consequently, predictions from the TSCE models based on these data may be biased when applied to the population at large. In addition, the biases may change over time if the risks from smoking or non-smoking factors (e.g. air pollution, radon, or second hand smoke) vary over time. To detect and correct for potential biases, we estimated regression models that allow for deviations in the predictions of lung cancer death rates of the ATC models from historical lung cancer death rates.

To control for population size, results from the TSCE models were converted to rates and calibrated against the lung cancer death rates rather than total lung cancer deaths. These models were estimated by gender using data aggregated over the 30 to 84 age group for each of the years from 1975 to 2000. We consider general trends for the population as a whole after netting out smoking factors, as incorporated in the TSCE models. Specifically, for each model, we regressed the historical lung cancer rates (HLCR) against the predicted lung cancer rates (PLCR) alone, PLCR interacted with time trends, and separate time trend factors:

where TT denotes a time trend (TT= 1 in 1975, TT = 2 in 1976, …, TT = 26 in 2000), subscript t = year (t= 1975, …, t = 2000), and e is the error term. The first part of the equation shows the influence of smoking as predicted by the TSCE model (b1) with any constant deviation (b0), while the next two terms correct the predictions of the smoking model for linear (b2) and non-linear (b3) biases over time. The second part of the equation allows for linear (a1) and non-linear (a2) trends not captured by the smoking model. We also estimated log specifications of the above model, which imply a proportional rather than constant deviation of model predictions from the historical rates, and a multiplicative rather than linear relationship between the variables.

Because reliable data were not available for cohorts born before 1900, values in the SBC data were inferred for smoking rate variables for the older missing ages in the years 1975 to 1985. To check for bias in the method used to calculate these values, we included a correction factor in the estimation equation equal to the number of age years with missing variables: 10 = 1975, 9= 1976,…, 1= 1984, 0 = 1985 and above. The correction factor was generally insignificant and induced autocorrelation. Consequently, it was dropped from the model.

Our goal was to determine the most parsimonious model with the highest level of predictability and with predictions that were not systematically biased over time. Predictability was gauged by the adjusted R-square. Systematically biased predictions were gauged by autocorrelation in the error terms. The Durbin-Watson (D-W) statistic was used to test for first order correlation of the error terms et and et−1. We began with a simple model that regressed HLCR on PLCR and a constant term. We then added variables to the equation, and kept those variables in the equation if the coefficient of the variable had a t-statistic < 1 (i.e., which lowers the adjusted R-square) or if autocorrelation was reduced.

2.d. Lung Cancer Deaths under the No, Actual and Complete Tobacco Control Scenarios

For each of the 4 models (male and female TSCE CPS-I and TSCE CPS-II) we compared predicted lung cancer death rates under the NTC, ATC and CTC scenarios. We consider uncalibrated and calibrated models. To calibrate the counterfactual NTC and CTC predictions we applied the best-fitting calibration equations from the ATC model (for the corresponding gender and CPS model) to the predicted lung cancer rates for NTC and CTC. We also calibrated by multiplying the NTC and CTC predicted rates by a correction factor, measured as the ratio of the historical to the corresponding (gender, year and CPS-type data set) ATC rates. Corrections were separately applied to each estimate of lung cancer deaths in two ways: using a measure 1) aggregated over all ages by year and 2) distinguished by each age and year.

The number of deaths avoided as a result of tobacco control policies was calculated as the difference in deaths between the ATC and NTC scenarios. The number of deaths that could have been avoided if smoking was entirely eliminated in 1965 was calculated as the difference in deaths between the ATC and CTC scenarios.

3. RESULTS

3.a. Predictions of Lung Cancer Deaths Rates from the TSCE Smoking Models

Historical male lung cancer death rates for those ages 30 to 84 increase through 1982, plateau through 1987, and then fall from 1988 onward. Both male TSCE models predict levels of lung cancer rates that are considerably less than historical rates. The trend pattern predicted by the CPS-I model is similar to that of historical lung cancer rates, with similar percentage increases albeit at a lower initial level from 1975 to 1981. The lung cancer rates predicted by the male CPS-II model begin to decline almost immediately but are considerably closer to historical rates than the CPS-I model. For males in the 30 to 49 age group, historical lung cancer death rates followed a continual downward trend with some flattening beginning in 1990. The rates predicted by the CPS-I and CPS-II models showed similar patterns, but with less decline and were generally less than historical rates. Unlike higher ages, rates predicted by the CPS-I model were greater than those from the CPS-II model for those below age 50. Historical rates of males in the 50 to 69 and 70 to 84 age groups increased until about 1990 and then declined, with a steeper decline in the 50 to 69 age group. Generally, the male models under-predict historical rates; the CPS-I models better mirrored changes in trends, but predictions from the CPS-II models were closer to historical rates and mirrored trends from 1990 to 2000. The projected trends from both models converged toward historical rates for those at lower ages, but diverged for those above age 70.

For females, historical lung cancer death rates increased over the years 1975 to 2000, but began to flatten around 1990. Although the rates predicted by the CPS-I model show a similar trend to the historical rates, the gap widens, with a 50% relative difference from historical rates in 1975 increasing to 75% in 2000. The rates predicted by the CPS-II model are only 10% lower than historical rates in 1975, but the gap increases to about 40% in 2000. For females age 30 to 49, the CPS-I and CPS-II models were considerably below historical rates and did not fall as rapidly over time. For females age 50 to 69, historical rates increased quite rapidly through 1993 and then fell. The predictions of the two models, especially the CPS-I model, were below historical rates and their trends were much flatter. For females age 70 to 84, the upward trend exhibited by both models, especially the CPS-I model, was considerably less than the historical rates. The CPS-II model, and to a much greater extent the CPS-I model, predicted female lung cancer death rates below historical rates, but both under-predicted the change in rates relative to historical changes. Like for males, the projected trends from both models converged toward historical rates for those at younger ages, but diverged for those at older ages.

The TSCE smoking models predicted that lung cancer death rates vary little over time for male never smokers, but unlike previous studies20, 21 indicate that the rates differ considerably by gender and whether CPS-I or CPS-II data are applied. Rates decrease over time for male smokers, but stay relatively constant for female smokers. Again, the rates differ considerably by gender and whether CPS-I or CPS-II data is applied. Different patterns are also observed for male former smokers from the CPS-I and CPS-II models, increasing until about 1990 and then decreasing more dramatically in CPS-II than in CPS-I. For female former smokers, the CPS-I and the CPS-II models predict a rapid rise until 1995 and then a taper off. For both genders, the CPS-II model predicts higher death rates than the CPS-I model for current and former smokers, but lower rates for never smokers.

3.b. Calibration of Predictions of the ATC Model to Historical Lung Cancer Death Rates

Tables I.a and I.b show the results from the calibration equations for males and females respectively. For both the log and linear models, the predictability improved and autocorrelation was reduced to acceptable levels when PLCR variables were interacted with time trends.

Table I.a.

Calibration of TSCE Model Predictions to Historical Data for Male Lung Cancer Death Rates

| Model | Constant | Linear time trend | Quadratic time trend | Predicted rate per 100K pop | Predicted * Time Trend | Predicted * Quad. Time Trend | R Square | Adjusted R Square | Eqn, Std. Error | Durbin-Watson |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

CPS-I: Linear Form

| ||||||||||

| 1 | 29.5 | 1.28 | 0.830 | 0.822 | 4.095 | 0.13** | ||||

| t-stat | 3.1 | 10.81 | ||||||||

| sig | 0.0 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| 2 | −68.5 | 2.31 | 0.016 | 0.952 | 0.948 | 2.218 | 0.43** | |||

| t-stat | −5.0 | 15.49 | 7.67 | |||||||

| sig | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||||

| 3 | 121.1 | 0.07 | 0.032 | −0.0016 | 0.992 | 0.991 | 0.902 | 1.70 | ||

| t-stat | 6.6 | 0.34 | 18.6 | −10.8 | ||||||

| sig | <0.001 | 0.74 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| 4 | 127.3 | 0.032 | −0.0017 | 0.992 | 0.992 | 0.885 | 1.70 | |||

| t-stat | 221.1 | 27.5 | −40.4 | |||||||

| sig | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||||

| 5 | 131.3 | −7.42 | 0.098 | 0.989 | 0.988 | 1.060 | 1.51* | |||

| t-stat | 215.1 | −33.6 | 29.5 | |||||||

| sig | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||||

| 6 | 128.3 | −1.93 | 0.049 | −0.0012 | 0.993 | 0.992 | 0.876 | 1.89 | ||

| t-stat | 127.3 | −1.19 | 3.40 | −3.41 | ||||||

| sig | <0.001 | 0.25 | 0.003 | 0.0030 | ||||||

| 7 | 107.8 | −2.83 | 0.25 | 0.056 | −0.0009 | 0.993 | 0.992 | 0.875 | 1.98 | |

| t-stat | 5.4 | −1.54 | 0.24 | 0.016 | 0.0010 | |||||

| sig | <0.001 | 0.14 | 0.31 | 0.002 | 0.10 | |||||

| Natural Log Form | ||||||||||

| 8 | 1.41 | 0.79 | 0.844 | 0.837 | 0.03114 | 0.14* | ||||

| t-stat | 4.63 | 11.38 | ||||||||

| sig | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| 9 | −1.96 | 1.53 | 0.0022 | 0.949 | 0.945 | 0.018 | 0.41** | |||

| t-stat | −3.80 | 13.47 | 6.96 | |||||||

| sig | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||||

| 10 | 4.85 | 0.0043 | −0.00023 | 0.992 | 0.991 | 0.0070 | 1.78 | |||

| t-stat | 1086.2 | 25.1 | −36.69 | |||||||

| sig | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||||

| 11 | 3.36 | −0.20 | 0.34 | 0.047 | 0.992 | 0.991 | 0.0072 | 1.92 | ||

| t-stat | 6.42 | −11.04 | 2.90 | 11.6 | ||||||

| sig | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.01 | <0.001 | ||||||

| 12 | 3.66 | −0.00076 | 0.27 | 0.0038 | 0.993 | 0.992 | 0.0067 | 1.98 | ||

| t-stat | 7.25 | −12.02 | 2.37 | 21.45 | ||||||

| sig | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.03 | <0.001 | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||

|

CPS-II: Linear Form

| ||||||||||

| 1 | 65.84 | 0.62 | 0.741 | 0.730 | 5.051 | 0.11** | ||||

| t-stat | 8.29 | 8.28 | ||||||||

| sig | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| 2 | −46.98 | 1.44 | 0.019 | 0.947 | 0.943 | 2.326 | 0.41** | |||

| t-stat | −3.78 | 15.43 | 9.49 | |||||||

| sig | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||||

| 3 | 146.95 | −0.17 | 0.026 | −0.0010 | 0.991 | 0.991 | 0.929 | 1.60* | ||

| t-stat | 8.06 | −1.12 | 25.80 | −11.05 | ||||||

| sig | <0.001 | 0.27 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| 4 | 126.5 | 0.025 | −0.0010 | 0.991 | 0.991 | 0.934 | 1.50* | |||

| t-stat | 203.1 | 27.16 | −39.95 | |||||||

| sig | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||||

| 5 | 130.1 | −5.53 | 0.057 | 0.992 | 0.991 | 0.920 | 1.84 | |||

| t-stat | 234.7 | −40.6 | 34.04 | |||||||

| sig | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||||

| 6 | 128.3 | −2.90 | 0.042 | −0.00062 | 0.993 | 0.992 | 0.863 | 1.96 | ||

| t-stat | 128.2 | −2.23 | 5.56 | −2.04 | ||||||

| sig | <0.001 | 0.04 | <0.001 | 0.05 | ||||||

| 7 | 127.7 | −2.93 | 0.0054 | 0.042 | −0.00061 | 0.993 | 0.992 | 0.883 | 1.96 | |

| t-stat | 6.30 | −1.83 | 0.03 | 4.66 | −1.30 | |||||

| sig | <0.001 | 0.08 | 0.98 | <0.001 | 0.21 | |||||

| Natural Log Form | ||||||||||

| 8 | 2.48 | 0.51 | 0.774 | 0.765 | 0.03743 | 0.12** | ||||

| t-stat | 9.43 | 9.07 | ||||||||

| sig | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| 9 | −1.80 | 1.39 | 0.0036 | 0.945 | 0.939 | 0.019 | 0.39** | |||

| t-stat | −3.42 | 12.88 | 8.42 | |||||||

| sig | 0.0023 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||||

| 10 | 4.85 | 0.0041 | −0.00021 | 0.993 | 0.992 | 0.0069 | 1.82 | |||

| t-stat | 1093.4 | 25.7 | −37.5 | |||||||

| sig | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||||

| 11 | 3.80 | −0.17 | 0.22 | 0.04 | 0.993 | 0.991 | 0.0070 | 2.030 | ||

| t-stat | 7.63 | −12.2 | 2.14 | 13.45 | ||||||

| sig | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.04 | <0.001 | ||||||

| 12 | 3.77 | −0.0008 | 0.225 | 0.0038 | 0.993 | 0.992 | 0.0067 | 1.98 | ||

| t-stat | 7.87 | −12.6 | 2.26 | 24.9 | ||||||

| sig | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.033855 | <0.001 | ||||||

Table I.b.

Calibration of TSCE Model Predictions to Historical Data for Female Lung Cancer Death Rates

| Model | (Constant) | Linear time trend | Quadratic time trend | Predicted rate per 100K pop | Predicted * Time Trend | Predicted * Quad. Time Trend | R Square | Adjusted R Square | Std. Error of the Estimate | Durbin-Watson |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

CPS-I: Linear Form

| ||||||||||

| 1 | −127.6 | 9.69 | 0.936 | 0.934 | 3.312 | 0.12** | ||||

| t-stat | −12.9 | 18.77 | ||||||||

| sig | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| 2 | −54.7 | 5.32 | 0.04 | 0.994 | 0.993 | 1.055 | 0.60** | |||

| t-stat | −9.3 | 15.56 | 14.61 | |||||||

| sig | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| 3 | 105.7 | −4.79 | 0.27 | −0.01 | 0.998 | 0.998 | 0.573 | 2.05 | ||

| t-stat | 4.9 | −3.51 | 8.79 | −7.49 | ||||||

| sig | < 0.001 | 0.00 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| 4 | 29.6 | 0.16 | −0.003 | 0.997 | 0.997 | 0.700 | 1.23** | |||

| t-stat | 72.0 | 44.84 | −24.07 | |||||||

| sig | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| 5 | 40.9 | −7.04 | 0.42 | 0.937 | 0.932 | 3.353 | 0.14** | |||

| t-stat | 16.2 | −1.80 | 2.22 | |||||||

| sig | <0.001 | 0.08 | 0.04 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| 6 | 31.3 | −2.62 | 0.29 | −0.003 | 0.998 | 0.998 | 0.543 | 2.19 | ||

| t-stat | 59.8 | −4.04 | 9.31 | −29.26 | ||||||

| sig | < 0.001 | 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| 7 | 57.1 | −1.95 | −1.65 | 0.29 | 0.00 | 0.998 | 0.998 | 0.548 | 2.26 | |

| t-stat | 1.64 | −1.74 | −0.74 | 9.14 | −3.07 | |||||

| sig | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.47 | <0.001 | 0.01 | |||||

|

| ||||||||||

|

Natural Log Form

| ||||||||||

| 8 | −2.37 | 2.29 | 0.996 | 0.996 | 0.01595 | 0.68** | ||||

| t-stat | −28.4 | 76.8 | ||||||||

| sig | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| 9 | −1.70 | 2.03 | 0.0010 | 0.998 | 0.997 | 0.01245 | 1.11** | |||

| t-stat | −12.12 | 38.14 | 5.29 | |||||||

| sig | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| 10 | 3.44 | 0.02 | −0.00053 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.00008 | 2.43 | |||

| t-stat | 626.16 | 76.35 | −46.21 | |||||||

| sig | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| 11 | −3.00 | −0.1113 | 2.340043 | 0.04 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.00011 | 1.73 | ||

| t-stat | −16.92 | −3.11 | 37.72 | 3.43 | ||||||

| sig | < 0.001 | < 0.002 | < 0.001 | < 0.000 | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| 12 | 1.66 | −0.0010 | 0.644 | 0.019 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.00876 | 2.39 | ||

| t-stat | 1.70 | −4.94 | 1.83 | 6.20 | ||||||

| sig | 0.103 | <0.001 | 0.081 | <0.001 | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||

|

CPS-II: Linear Form

| ||||||||||

| 1 | −57.50 | 2.91 | 0.878 | 0.873 | 4.576 | 0.09** | ||||

| t-stat | −6.52 | 13.16 | ||||||||

| sig | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| 2 | −7.50 | 1.31 | 0.02 | 0.996 | 0.995 | 0.866 | 0.82** | |||

| t-stat | −2.91 | 17.40 | 25.43 | |||||||

| sig | 0.01 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| 3 | 48.56 | −0.60 | 0.09 | −0.0020 | 0.998 | 0.998 | 0.540 | 2.20 | ||

| t-stat | 5.21 | −1.90 | 8.14 | −6.10 | ||||||

| sig | <0.001 | 0.07 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| 4 | 30.82 | 0.07 | −0.0014 | 0.998 | 0.998 | 0.570 | 1.82 | |||

| t-stat | 96.76 | 53.8 | −27.0 | |||||||

| sig | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| 5 | 40.54 | −5.28 | 0.16 | 0.964 | 0.961 | 2.525 | 0.23** | |||

| t-stat | 30.43 | −3.92 | 5.12 | |||||||

| sig | <0.001 | 0.00 | <0.001 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| 6 | 31.42 | −0.54 | 0.08 | −0.0013 | 0.998 | 0.998 | 0.557 | 2.04 | ||

| t-stat | 60.44 | −1.44 | 10.91 | −21.24 | ||||||

| sig | <0.001 | 0.16 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| 7 | 60.34 | 0.53 | −1.03 | 0.10 | −0.0024 | 0.998 | 0.998 | 0.548 | 2.24* | |

| t-stat | 2.74 | 0.59 | −1.31 | 6.99 | −2.82 | |||||

| sig | 0.01 | 0.56 | 0.20 | <0.001 | 0.010 | |||||

|

| ||||||||||

|

Natural Log Form

| ||||||||||

| 8 | −3.71 | 2.11 | 0.920 | 0.916 | 0.0711 | 0.084** | ||||

| t-stat | −7.94 | 16.57 | ||||||||

| sig | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| 9 | −0.73 | 1.24 | 0.0041 | 0.998 | 0.997 | 0.0123 | 1.12** | |||

| t-stat | −5.46 | 32.5 | 27.8 | |||||||

| sig | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| 10 | 3.44 | 0.019 | −0.00041 | 0.998 | 0.998 | 0.0092 | 2.21 | |||

| t-stat | 612.0 | 73.4 | −43.8 | |||||||

| sig | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| 11 | −0.52 | −0.07 | 1.18 | 0.02 | 0.998 | 0.998 | 0.0104 | 1.71 | ||

| t-stat | −3.93 | −3.22 | 32.1 | 3.91 | ||||||

| sig | <0.001 | 0.00 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| 12 | 1.91 | 0.00 | 0.45 | 0.01 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.0090 | 2.30 | ||

| t-stat | 3.31 | −4.64 | 2.65 | 6.65 | ||||||

| sig | 0.003 | <0.001 | 0.01 | <0.001 | ||||||

For the both the CPS-I and CPS-II male linear models, serial correlated errors were detected, except when both the PLCRt*TTt and PLCRt*TTt2 variables were included in the estimation equation. In addition, the adjusted R-square was marginally higher when the noninteracted PLCR variable was dropped and the D-W statistic and adjusted R-square improved when a non-interacted time trend variable was added for both models. The CPS-I and CPS-II linear models with the PLCRt*TTt, PLCRt*TTt2 and TT variables (eqn. 6) have strong explanatory power (as indicated by R-square values that exceed 0.99), exhibit no significant autocorrelation (i.e. the D-W statistic is within the 1.7–2.3 range), and all coefficients are statistically significant. For the log models, the equations with a non-interacted PLCRt and PLCRt*TTt (eqn. 10 for CPS-I and CPS-II) performed best in terms of non-serially correlated errors and the adjusted R-square (above 0.99). When a non-interacted time trend was added, its coefficient was significant and autocorrelation was reduced (eqn. 11).

Similar to the male models, the variables PLCRt*TTt and PLCRt*TTt2 were required in the linear models for females to reduce autocorrelation to insignificant levels. For the CPS-I model, the equations with PLCRt*TTt and PLCRt*TTt2 (eqn. 4) or with PLCRt*TTt and PLCRt*TTt2 and TTt (eqn. 6) performed best in terms of the D-W statistic and the adjusted R-square. For the CPS-II linear model, the adjusted R-squares were higher when the non-interacted PLCR variable was dropped (eqns. 4 and 6), and the D-W statistic improved when a non-interacted TT variable was added (eqn. 6). In log form, the CPS-I models with either the variables PLCRt*TTt and PLCRt*TTt2 or with the variables PLCRt and PLCRt*TTt and TTt2 performed best. The log model with PLCRt, PLCRt*TTt and TTt induced severe autocorrelation. The CPS-II female models in log form performed about equally well in terms of autocorrelation and the adjusted R-square when either the variables PLCRt, PLCRt*TTt and TTt (eqn. 11) or PLCRt*TTt and PLCRt*TTt2 (eqn. 12) were included. These models, along with equations 4 and 6, had adjusted R-square values above 0.99 and no detectable autocorrelation in the error terms.

3. Lives Saved and Potential Lives Saved from Tobacco Control

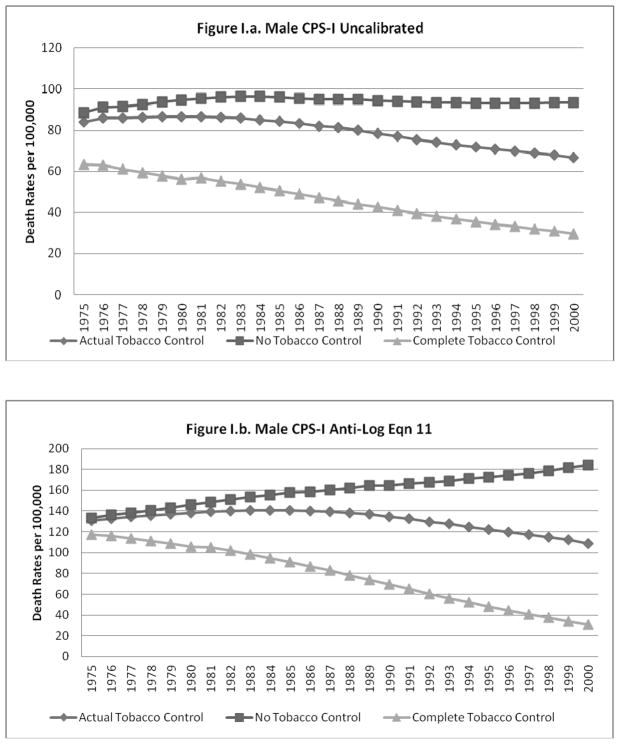

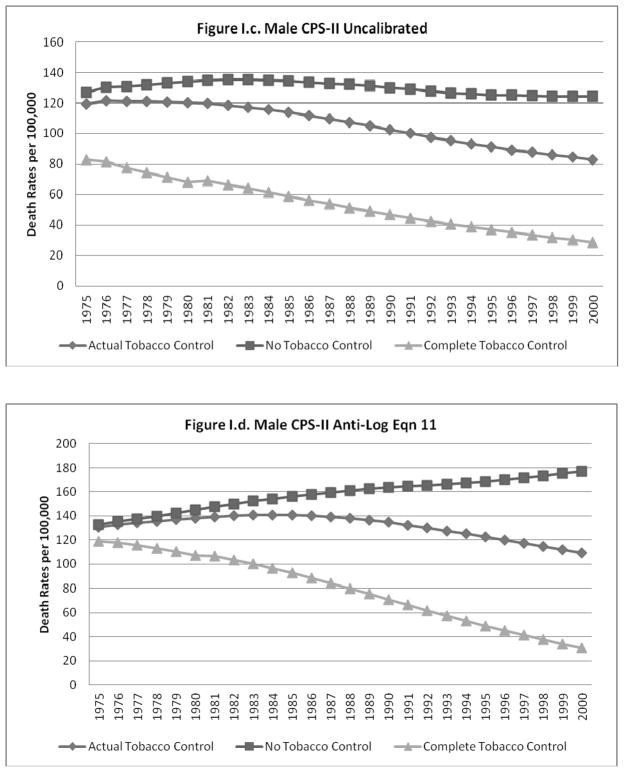

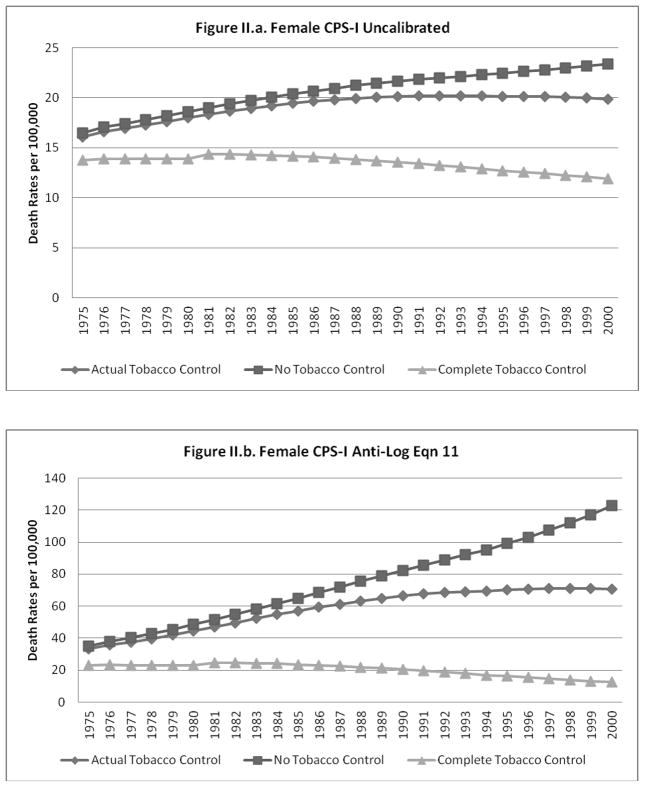

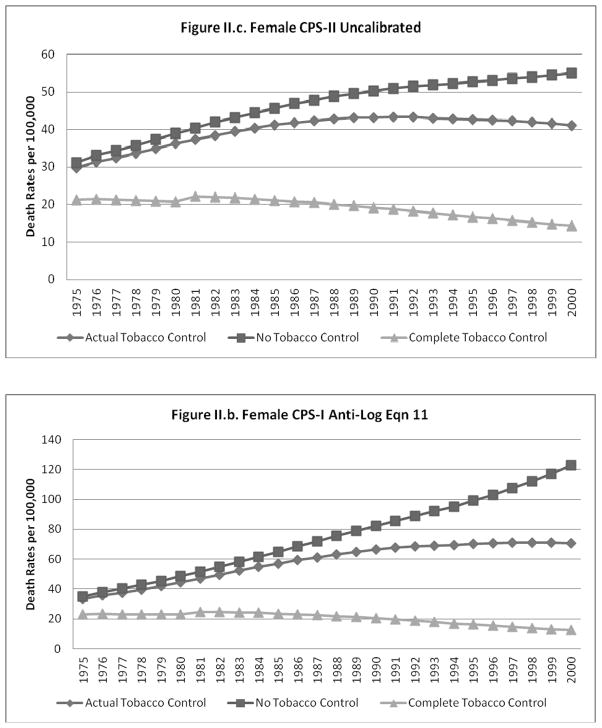

The predicted lung cancer rates (un-calibrated and calibrated to equation 11) for the NTC, ATC and CTC cases are shown for males and females, respectively, in Figures I.a–I.d. and II.a.–II.d. The figures each show that, as expected, the gap between the NTC and ATC and between the ATC and CTC scenarios grows over time for all cases. The un-calibrated results from the CPS-II model for each scenario are higher than those from the CPS-I model for males and females, with a larger relative gap for females.

Figure I.

Figure II.

When calibration equations other than equation 11 were applied to the predictions from the models using the NTC and CTC data, the calibrated predictions did not always yield plausible estimates for the CTC and NTC cases (i.e., CTC>ATC>NTC was violated). In particular, some of the better models that did not have a non-interacted time trend (e.g., equations 6 and 10) were not robust to the large deviations in smoking rates imputed to the CTC and NTC scenarios. The model predictions for males and females calibrated to equations 6 and 11 (results shown for equation 11), model predictions for males and females calibrated to the ratio of historical to predicted ATC rates, and model predictions for females calibrated to equation 13 showed patterns similar to those exhibited for the un-calibrated cases (i.e., CTC>ATC>NTC in roughly similar proportions).

The estimates of lung cancer deaths for NTC, ATC and CTC under each of the consistent calibrated estimates as well as for the un-calibrated estimates scenarios are shown for the male and female cases, respectively, in Tables II.a. and II.b. In addition, for each of the calibrated and un-calibrated cases, these tables show the lives saved from tobacco control (CTC deaths –ATC deaths) and the lives that could have been saved by eliminating smoking in 1965 (CTC deaths – NTC deaths), and the last column sums these estimates over all years.

Table II.a.

Lung Cancer Deaths under No, Actual and Complete Tobacco Control and Actual and Potential Lives Saved, Males

| Year | 1975 | 1980 | 1985 | 1990 | 1995 | 2000 | Cumulative* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Historical Lung Cancer Deaths | 61,601 | 72,854 | 80,405 | 86,642 | 86,223 | 83,973 | 2,067,775 |

|

| |||||||

|

CPS-I

| |||||||

| Uncalibrated | |||||||

| No Tobacco Control | 42,092 | 49,464 | 55,289 | 59,995 | 65,813 | 71,445 | 1,494,827 |

| Actual Tobacco Control | 39,927 | 45,319 | 48,485 | 49,872 | 50,792 | 51,014 | 1,247,860 |

| Complete Tobacco Control | 30,137 | 29,351 | 29,073 | 27,121 | 25,079 | 22,691 | 715,555 |

| Lives Saved By Tobacco Control | 2,166 | 4,146 | 6,803 | 10,122 | 15,021 | 20,431 | 246,967 |

| Potential Lives saved | 11,955 | 20,114 | 26,215 | 32,874 | 40,734 | 48,754 | 779,271 |

|

| |||||||

| Calibrated to Equation6 | |||||||

| No Tobacco Control | 62,156 | 73,424 | 83,246 | 90,318 | 94,389 | 91,748 | 2,175,285 |

| Actual Tobacco Control | 62,052 | 72,382 | 80,571 | 85,526 | 86,996 | 82,564 | 2,067,879 |

| Complete Tobacco Control | 61,582 | 68,369 | 72,940 | 74,755 | 74,341 | 69,834 | 1,852,231 |

| Lives Saved By Tobacco Control | 104 | 1,042 | 2,674 | 4,792 | 7,393 | 9,183 | 107,406 |

| Potential Lives saved | 574 | 5,055 | 10,305 | 15,562 | 20,048 | 21,913 | 323,053 |

|

| |||||||

| Calibrated to Equation11 | |||||||

| No Tobacco Control | 63,478 | 76,200 | 90,474 | 104,758 | 121,753 | 140,531 | 2,575,185 |

| Actual Tobacco Control | 62,193 | 72,171 | 80,872 | 85,675 | 86,445 | 83,213 | 2,067,757 |

| Complete Tobacco Control | 55,780 | 55,114 | 52,241 | 44,153 | 34,008 | 23,595 | 1,173,446 |

| Lives Saved By Tobacco Control | 1,284 | 4,030 | 9,602 | 19,083 | 35,308 | 57,317 | 507,428 |

| Potential Lives saved | 7,698 | 21,086 | 38,233 | 60,604 | 87,746 | 116,935 | 1,401,739 |

|

| |||||||

| Calibrated to historical by year | |||||||

| No Tobacco Control | 64,942 | 79,519 | 91,687 | 104,228 | 111,722 | 117,605 | 2,481,113 |

| Actual Tobacco Control | 61,601 | 72,854 | 80,405 | 86,642 | 86,223 | 83,973 | 2,067,775 |

| Complete Tobacco Control | 46,497 | 47,184 | 48,213 | 47,117 | 42,573 | 37,351 | 1,181,256 |

| Lives Saved By Tobacco Control | 3,341 | 6,665 | 11,282 | 17,586 | 25,499 | 33,632 | 413,338 |

| Potential Lives saved | 18,445 | 32,334 | 43,474 | 57,111 | 69,148 | 80,254 | 1,299,857 |

|

| |||||||

| Calibrated to historical by age and year | |||||||

| No Tobacco Control | 68,683 | 81,785 | 91,070 | 99,221 | 101,226 | 102,688 | 2,379,571 |

| Actual Tobacco Control | 61,601 | 72,854 | 80,405 | 86,642 | 86,223 | 83,966 | 2,067,768 |

| Complete Tobacco Control | 49,077 | 48,168 | 47,444 | 44,145 | 38,238 | 32,363 | 1,139,192 |

| Lives Saved By Tobacco Control | 7,082 | 8,931 | 10,665 | 12,579 | 15,003 | 18,722 | 311,803 |

| Potential Lives saved | 19,605 | 33,618 | 43,626 | 55,075 | 62,988 | 70,326 | 1,240,379 |

|

| |||||||

| CPS-II | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Uncalibrated | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| No Tobacco Control | 60,063 | 69,660 | 76,728 | 82,042 | 87,917 | 94,150 | 2,045,876 |

| Actual Tobacco Control | 56,691 | 62,915 | 65,492 | 65,197 | 64,440 | 63,149 | 1,653,626 |

| Complete Tobacco Control | 39,380 | 35,560 | 33,820 | 29,832 | 25,982 | 21,832 | 815,132 |

| Lives Saved By Tobacco Control | 3,371 | 6,745 | 11,236 | 16,845 | 23,476 | 31,001 | 392,250 |

| Potential Lives saved | 20,683 | 34,099 | 42,907 | 52,211 | 61,935 | 72,318 | 1,230,744 |

|

| |||||||

| Calibrated to Eqn 6 | |||||||

| No Tobacco Control | 62,170 | 73,927 | 85,022 | 94,099 | 101,051 | 103,691 | 2,271,775 |

| Actual Tobacco Control | 62,031 | 72,383 | 80,689 | 85,480 | 86,804 | 82,880 | 2,067,779 |

| Complete Tobacco Control | 61,317 | 66,124 | 68,475 | 67,385 | 63,464 | 55,145 | 1,684,055 |

| Lives Saved By Tobacco Control | 139 | 1,543 | 4,333 | 8,619 | 14,247 | 20,810 | 203,996 |

| Potential Lives saved | 853 | 7,803 | 16,547 | 26,714 | 37,587 | 48,546 | 587,720 |

|

| |||||||

| Calibrated to Eqn 11 | |||||||

| No Tobacco Control | 63,120 | 75,564 | 89,394 | 103,393 | 118,319 | 134,180 | 2,522,279 |

| Actual Tobacco Control | 62,182 | 72,204 | 80,858 | 85,613 | 86,500 | 83,237 | 2,067,762 |

| Complete Tobacco Control | 56,574 | 55,962 | 53,186 | 45,054 | 34,613 | 23,379 | 1,192,307 |

| Lives Saved By Tobacco Control | 939 | 3,360 | 8,536 | 17,780 | 31,819 | 50,943 | 454,517 |

| Potential Lives saved | 6,546 | 19,601 | 36,207 | 58,339 | 83,706 | 110,800 | 1,329,972 |

|

| |||||||

| Calibrated to historical by year | |||||||

| No Tobacco Control | 65,264 | 80,664 | 94,199 | 109,028 | 117,635 | 125,196 | 2,574,942 |

| Actual Tobacco Control | 61,601 | 72,854 | 80,405 | 86,642 | 86,223 | 83,973 | 2,067,775 |

| Complete Tobacco Control | 42,790 | 41,178 | 41,522 | 39,644 | 34,764 | 29,032 | 1,006,122 |

| Lives Saved By Tobacco Control | 3,663 | 7,810 | 13,794 | 22,386 | 31,412 | 41,223 | 507,167 |

| Potential Lives saved | 22,474 | 39,486 | 52,677 | 69,384 | 82,871 | 96,164 | 1,568,820 |

|

| |||||||

| Calibrated to historical by age and year | |||||||

| No Tobacco Control | 67,851 | 83,161 | 96,602 | 111,444 | 119,706 | 127,127 | 2,635,305 |

| Actual Tobacco Control | 61,601 | 72,854 | 80,405 | 86,642 | 86,223 | 83,966 | 2,067,768 |

| Complete Tobacco Control | 44,191 | 42,204 | 42,605 | 40,899 | 36,739 | 31,472 | 1,045,067 |

| Lives Saved By Tobacco Control | 6,250 | 10,307 | 16,197 | 24,802 | 33,483 | 43,161 | 567,537 |

| Potential Lives saved | 23,660 | 40,957 | 53,997 | 70,544 | 82,967 | 95,655 | 1,590,238 |

Best estimate shaded in gray

Cumulative is summed over the years 1975 to 2000

Table II.b.

Lung Cancer Deaths under No, Actual and Complete Tobacco Control and Actual and Potential Lives Saved, Females

| Year | 1975 | 1980 | 1985 | 1990 | 1995 | 2000 | Cumulative* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Historical Lung Cancer Deaths | 17,724 | 26,794 | 36,686 | 47,089 | 54,499 | 58,589 | 1,051,978 |

|

| |||||||

|

CPS-I

| |||||||

| Uncalibrated | |||||||

| No Tobacco Control | 8,904 | 11,021 | 13,157 | 15,288 | 17,364 | 19,314 | 368,797 |

| Actual Tobacco Control | 8,697 | 10,666 | 12,571 | 14,225 | 15,575 | 16,423 | 340,977 |

| Complete Tobacco Control | 7,436 | 8,233 | 9,148 | 9,592 | 9,840 | 9,850 | 236,868 |

| Lives Saved By Tobacco Control | 208 | 356 | 586 | 1,062 | 1,789 | 2,891 | 27,820 |

| Potential Lives saved | 1,468 | 2,788 | 4,010 | 5,696 | 7,524 | 9,463 | 131,929 |

|

| |||||||

| Calibrated to Equation 6 | |||||||

| No Tobacco Control | 18,006 | 27,120 | 38,618 | 51,403 | 64,020 | 75,485 | 1,184,607 |

| Actual Tobacco Control | 17,946 | 26,542 | 36,968 | 47,306 | 55,531 | 59,625 | 1,066,479 |

| Complete Tobacco Control | 17,586 | 22,586 | 27,327 | 29,439 | 28,313 | 23,570 | 667,494 |

| Lives Saved By Tobacco Control | 59 | 578 | 1,650 | 4,097 | 8,489 | 15,860 | 118,128 |

| Potential Lives saved | 420 | 4,534 | 11,292 | 21,963 | 35,707 | 51,915 | 517,113 |

|

| |||||||

| Calibrated to Equation 11 | |||||||

| No Tobacco Control | 18,939 | 28,743 | 41,868 | 58,052 | 76,618 | 101,273 | 1,378,437 |

| Actual Tobacco Control | 17,905 | 26,408 | 36,875 | 46,802 | 54,143 | 58,382 | 1,051,902 |

| Complete Tobacco Control | 12,333 | 13,527 | 15,201 | 14,401 | 12,492 | 10,284 | 350,179 |

| Lives Saved By Tobacco Control | 1,034 | 2,335 | 4,993 | 11,250 | 22,475 | 42,892 | 326,535 |

| Potential Lives saved | 6,606 | 15,216 | 26,667 | 43,650 | 64,126 | 90,989 | 1,028,258 |

|

| |||||||

| Calibrated to historical by year | |||||||

| No Tobacco Control | 18,147 | 27,687 | 38,396 | 50,606 | 60,758 | 68,903 | 1,143,972 |

| Actual Tobacco Control | 17,724 | 26,794 | 36,686 | 47,089 | 54,499 | 58,589 | 1,051,978 |

| Complete Tobacco Control | 15,155 | 20,683 | 26,694 | 31,751 | 34,432 | 35,142 | 719,394 |

| Lives Saved By Tobacco Control | 423 | 893 | 1,710 | 3,517 | 6,259 | 10,314 | 91,994 |

| Potential Lives saved | 2,992 | 7,005 | 11,702 | 18,855 | 26,326 | 33,761 | 424,578 |

|

| |||||||

| Calibrated to historical by age and year | |||||||

| No Tobacco Control | 20,160 | 29,685 | 40,381 | 52,515 | 62,470 | 70,303 | 1,192,352 |

| Actual Tobacco Control | 18,544 | 28,216 | 38,585 | 50,088 | 59,263 | 64,987 | 1,128,150 |

| Complete Tobacco Control | 14,164 | 8,233 | 9,148 | 9,592 | 9,840 | 9,850 | 243,596 |

| Lives Saved By Tobacco Control | 1,616 | 1,469 | 1,796 | 2,427 | 3,207 | 5,316 | 64,202 |

| Potential Lives saved | 5,996 | 21,452 | 31,233 | 42,923 | 52,630 | 60,453 | 948,756 |

|

| |||||||

|

CPS-II

| |||||||

| Uncalibrated | |||||||

| No Tobacco Control | 16,821 | 22,995 | 29,416 | 35,436 | 40,712 | 45,419 | 829,940 |

| Actual Tobacco Control | 16,054 | 21,414 | 26,585 | 30,504 | 32,975 | 33,846 | 708,994 |

| Complete Tobacco Control | 11,435 | 12,226 | 13,612 | 13,525 | 12,885 | 11,791 | 333,880 |

| Lives Saved By Tobacco Control | 767 | 1,581 | 2,831 | 4,932 | 7,737 | 11,574 | 120,947 |

| Potential Lives saved | 5,386 | 10,770 | 15,805 | 21,912 | 27,827 | 33,628 | 496,060 |

|

| |||||||

| Calibrated to Eqn 6 | |||||||

| No Tobacco Control | 18,053 | 27,152 | 38,879 | 51,665 | 63,573 | 73,002 | 1,178,858 |

| ActualTobacco Control | 17,989 | 26,434 | 36,725 | 46,721 | 54,454 | 58,081 | 1,052,000 |

| Complete Tobacco Control | 17,610 | 22,259 | 26,851 | 29,699 | 30,778 | 29,647 | 693,353 |

| Lives SavedBy Tobacco Control | 63 | 718 | 2,155 | 4,944 | 9,118 | 14,921 | 126,858 |

| Potential Lives saved | 443 | 4,893 | 12,029 | 21,966 | 32,795 | 43,355 | 485,505 |

|

| |||||||

| Calibrated to Eqn 11 | |||||||

| No Tobacco Control | 18,980 | 29,033 | 42,604 | 59,020 | 77,216 | 98,802 | 1,385,887 |

| Actual Tobacco Control | 17,941 | 26,420 | 36,822 | 46,726 | 54,238 | 58,306 | 1,051,912 |

| Complete Tobacco Control | 11,915 | 12,580 | 14,032 | 13,154 | 11,230 | 8,801 | 321,444 |

| Lives Saved By Tobacco Control | 1,039 | 2,612 | 5,782 | 12,294 | 22,978 | 40,496 | 333,976 |

| Potential Lives saved | 7,066 | 16,453 | 28,572 | 45,866 | 65,986 | 90,001 | 1,064,443 |

|

| |||||||

| Calibrated to historical by year | |||||||

| No Tobacco Control | 17,724 | 26,794 | 36,686 | 47,089 | 54,499 | 58,589 | 1,051,978 |

| Actual Tobacco Control | 16,916 | 24,952 | 33,155 | 40,535 | 44,142 | 43,660 | 895,568 |

| Complete Tobacco Control | 12,049 | 14,245 | 16,976 | 17,972 | 17,249 | 15,210 | 416,505 |

| Lives Saved By Tobacco Control | 808 | 1,842 | 3,531 | 6,554 | 10,357 | 14,929 | 156,410 |

| Potential Lives saved | 5,675 | 12,549 | 19,710 | 29,117 | 37,250 | 43,379 | 635,473 |

|

| |||||||

| Calibrated to historical by age and year | |||||||

| No Tobacco Control | 20,645 | 30,888 | 42,809 | 56,955 | 69,479 | 80,668 | 1,298,396 |

| Actual Tobacco Control | 18,544 | 28,216 | 38,585 | 50,088 | 59,263 | 64,987 | 1,128,150 |

| Complete Tobacco Control | 14,337 | 16,832 | 20,042 | 21,974 | 22,616 | 21,977 | 518,564 |

| Lives Saved By Tobacco Control | 2,101 | 2,672 | 4,224 | 6,867 | 10,216 | 15,681 | 170,246 |

| Potential Lives saved | 6,308 | 14,055 | 22,767 | 34,982 | 46,863 | 58,691 | 779,832 |

Best estimate shaded in gray

Cumulative is summed over the years 1975 to 2000

For males, the number of lives potentially saved from eliminating smoking in 1965 (the difference between NTC and CTC) is substantially lower for the un-calibrated CPS-I (779,271 lives saved over the period 1975 to 2000) than the un-calibrated CPS-II (1,230,744 lives saved), as is expected due to the lower relative mortality risks that are obtained using the CPS-I compared to the CPS-II data. Using the calibration of the ATC predictions to historical rates, however, brings the estimates much closer together (e.g., 1,240,379 for CPS-I vs 1,590,238 for CPS-II), especially in relative terms. The prediction using the log model (equation 11) for the CPS-II models yielded estimates of lives saved between those of the estimates using the ratio of ATC to historical calibration and were very close to each other. The estimates using equation 6 were below those of the un-calibrated case and substantially below that of the other calibrated cases, suggesting that the linear specification implied in these equations is less plausible than the log specification. Our choice for best estimate is from the results using the log model (equation 11) calibrated to the CPS-II with bounds from the CPS-I model calibrated to the historical rates and the CPS-II calibrated to the historical rates. Our best estimates with bounds in parentheses are 454,517 (311,803 to 567,537) male lives saved as a result of actual tobacco control and the potential to have saved 1,329,972 (1,240,379 to 1,590,238) male lives with complete tobacco control beginning in 1965.

Results were generally less consistent for female models. Because the rates from the CPS-I model are far below those of the CPS-II model (reflecting the large difference in relative smoking risks), those results are not considered for best final estimates. For the CPS-II model, the number of potential lives saved over the period 1975 to 2000 from the linear calibration using equation 6 (485,505 potential lives saved) are close to the un-calibrated predictions (496,060 potential lives saved), but substantially less than half those of the log specification from equation 11 (1,064,443 potential lives saved). The midway CPS-II rates calibrated to historical rates are designated as best estimates, 132,034 lives saved as a result of actual tobacco control and 779,832 potential lives saved. Because of the wide disparity in results of the different CPS-II models, we designate the un-calibrated results from CPS-II as the lower bound and the results from CPS-II calibrated to equation 11 as the upper bound; we estimate 170,246 (120,947 to 333,976) female lives saved as a result of actual tobacco control and the potential to save 779,832 (496,060 to 1,064,443) female lives.

In total, we estimate that 624,763 lives were saved between 1975 and 2000 as a result of tobacco control activities and a potential 2,109,804 lives could have been saved from all together eliminating smoking as of 1966.

4. DISCUSSION

Using results from the original TSCE smoking models and from models adjusted over time, we estimated how many lung cancer deaths have been avoided as a result of reductions in smoking due to tobacco control efforts implemented since the early fifties and how many deaths could have been avoided if all smoking had stopped as of 1965. Our best estimate is that tobacco control activities saved approximately 625,000 lives that would have been lost to lung cancer between the years 1975 and 2000. An additional 2,110,000 lives would have been saved if all smoking ceased in the year 1965. However, the results varied considerably depending on the calibration scheme.

The estimates were based on separate TSCE models estimated using CPS-I and CPS-II data. The predictions of lung cancer death rates from TSCE models using the CPS-I and CPS-II data were compared to historical death rates. Some relatively consistent patterns were observed for males and females and for predictions from the TSCE model applied to the CPS-I and CPS-II data. We find that the predictions for the male and female TSCE models were considerably below historical rates, likely reflecting the non-representative, more highly educated sample of the CPS samples and misclassification error. As indicated by the graphical analysis and the statistical significance of the PLCRt*TTt and the PLCRt*TTt*TTt variables in the log and linear calibration equations, the deviations of the predictions to the historical rates increases over time. These results are consistent with findings that the relative lung cancer death risks found with the CPS-II data are higher than those found with the CPS-I data and may reflect an increasing relative risk e.g., from a more harmful effect of cigarettes alone or from a synergistic effect with non-smoking factors, such as radon. These results also indicate that there may be major bias in using CPS data to calculate lung cancer deaths attributable to smoking. The results indicate that these deaths may be seriously underestimated and the bias may be increasing over time.

Several other findings also merit further exploration. The convergence of the predictions to historical rates at younger ages may reflect reduced exposure to second hand smoke with the general reductions in smoking prevalence over time beginning in 1964. In addition, the significant, negative coefficient on the non-interacted time trend variable in all of the models, even after adjusting predictions of the smoking model for upward trends, suggests that there is still a residual (i.e., non-smoking) downward trend in lung cancer death rates that is not captured by the TSCE smoking models.

4.a. Limitations

Our analysis relates predictions of the smoking models to historical lung cancer death rates at an aggregated level, i.e., over all ages. In our analysis, age and cohort effects through smoking behaviors are assumed to be captured by the smoking models. The focus is on period effects as captured by time trends, although part of the effects may be due to cohort effects. The graphs by age indicate that age may be an important factor. We have begun to consider less aggregated smoking models calibrated at the level of age by year allowing for separate age related and cohort-related trends. While the relative roles of these effects are more difficult to distinguish, we have found important differences in age-related, trend-related and cohort-related deviations of the model from historical rates.

The TSCE smoking models that we apply to the smoking data are non-linear. Because the TSCE smoking models were estimated for individual ages, we captured nonlinearities as they apply to different ages. However, nonlinearities may exist within age groups due to the variation of duration and intensity among those of a particular age. Since duration and intensity are likely to be correlated, data is needed on their joint distributions in order to analyze those effects.

The TSCE smoking models that we apply do not distinguish racial-ethnic differences. Some previous studies indicate important differences in lung cancer rates and the role of smoking by race (2).

The predictions from the smoking models were calibrated over the entire range of years and ages. Consequently, results could only be compared across models and could not be validated for individual models.

Finally, our analysis of the role of smoking in lung cancer is based on empirical smoking models applying the two-stage clonal expansion model of cancer growth. We also conducted similar analyses using results from a study by Flanders et al.6 using the CPS-II data and from a study by Knoke et al.8 using the CPS-I data. We obtained roughly consistent results when comparing their results to the TSCE models using the same CPS data sets.

In sum, using the Smoking Base Case data, we were able to consider times series relationships between smoking rates and lung cancer deaths over a longer time period than previous longitudinal studies. The analyses conducted in this paper provide a first step in considering the robustness over time of estimates from studies using the CPS-I and CPS-II data. In particular, we consider biases in predictions stemming from the TSCE model and how these biases may be changing over time, but the extent of bias and trends in bias are dependent on whether CPS-I or CPS-II data is used to estimate the model. Our analysis, focusing on lung cancer rates at an aggregated level, indicates strong trends in how the effects of smoking and non-smoking related factors may have changed over time.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this work was from the Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network (CISNET) of the Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences (DCCPS), National Cancer Institute (NCI) under grant UO1-CA97450-02.

Footnotes

Competing Interests

There are no competing interests.

Contributor Information

David Levy, Georgetown University, Pacific Institute

Kenneth Blackman, Pacific Institute

Eduard Zaloshnja, Pacific Institute

References

- 1.Jemal A, Thun M, Ries LA, Howe HL, Weir HK. Annual Report to the Nation on the Status of Cancer, 1975–2005, Featuring Trends in Lung cancer, Tobacco Use, and Tobacco Control. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2008 doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thun MJ, Jemal A. How much of the decrease in cancer death rates in the United States is attributable to reductions in tobacco smoking? Tob Control. 2006;15(5):345–7. doi: 10.1136/tc.2006.017749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.USDHHS. The 2004 United States Surgeon General’s Report: The Health Consequences of Smoking. N S W Public Health Bull. 2004;15(5–6):107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Willemsen MC, de Vries H, Genders R. Annoyance from environmental tobacco smoke and support for no-smoking policies at eight large Dutch workplaces. Tob Control. 1996;5(2):132–8. doi: 10.1136/tc.5.2.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doll R, Peto R, Wheatley K, Gray R, Sutherland I. Mortality in relation to smoking: 40 years’ observations on male British doctors. BMJ. 1994;309(6959):901–11. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6959.901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flanders WD, Lally CA, Zhu BP, Henley SJ, Thun MJ. Lung cancer mortality in relation to age, duration of smoking, and daily cigarette consumption: results from Cancer Prevention Study II. Cancer Res. 2003;63(19):6556–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knoke JD, Shanks TG, Vaughn JW, Thun MJ, Burns DM. Lung Cancer Mortality Is Related to Age in Addition to Duration and Intensity of Cigarette Smoking: An Analysis of CPS-I Data. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13(6):949–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knoke JD, Burns DM, Thun MJ. The change in excess risk of lung cancer attributable to smoking following smoking cessation: an examination of different analytic approaches using CPS-I data. Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19(2):207–19. doi: 10.1007/s10552-007-9086-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meza R, Hazelton WD, Colditz GA, Moolgavkar SH. Analysis of lung cancer incidence in the Nurses’ Health and the Health Professionals’ Follow-Up Studies using a multistage carcinogenesis model. Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19(3):317–28. doi: 10.1007/s10552-007-9094-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hazelton WD, Clements MS, Moolgavkar SH. Multistage carcinogenesis and lung cancer mortality in three cohorts. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14(5):1171–81. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.CDC. Smoking-attributable mortality, years of potential life lost, and productivity losses--United States, 2000–2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57(45):1226–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garfinkel L. Selection, follow-up, and analysis in the American Cancer Society prospective studies. Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1985;67:49–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stellman SD, Garfinkel L. Smoking habits and tar levels in a new American Cancer Society prospective study of 1.2 million men and women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1986;76:1057–1063. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wells CK, Feinstein AR. Detection bias in the diagnostic pursuit of lung cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 1988;128(5):1016–26. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van de Mheen PJ, Gunning-Schepers LJ. Differences between studies in reported relative risks associated with smoking: an overview. Public Health Rep. 1996;111(5):420–6. discussion 427. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van de Mheen PJ, Gunning-Schepers LJ. Reported prevalences of former smokers in survey data: the importance of differential mortality and misclassification. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;140(1):52–7. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wells CK, Peduzzi PN, Feinstein AR. Presenting manifestations, cigarette smoking, and detection bias in age at diagnosis of lung cancer. Ann Epidemiol. 2001;11(4):239–47. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00213-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thun MJ, Heath CW., Jr Changes in mortality from smoking in two American Cancer Society prospective studies since 1959. Prev Med. 1997;26(4):422–6. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1997.0182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thun MJ, Day-Lally C, Myers DG, Calle EE, Flanders WD, Zhu B-P, et al. Institute NC. Changes in cigarette related disease risks and their implication for prevention and control. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 1997. Trends in tobacco smoking and mortality from cigarette use in Cancer Prevention Study I (1959–1965) and II (1982–1988) pp. 305–382. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thun MJ, Hannan LM, Adams-Campbell LL, Boffetta P, Buring JE, Feskanich D, et al. Lung Cancer Occurrence in Never-Smokers: An Analysis of 13 Cohorts and 22 Cancer Registry Studies. PLoS Med. 2008;5(9):e185. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thun MJ, Henley SJ, Burns D, Jemal A, Shanks TG, Calle EE. Lung cancer death rates in lifelong nonsmokers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(10):691–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]