Abstract

The Th17 immune response appears to contribute to the pathogenesis of human and experimental crescentic GN, but the cell types that produce IL-17A in the kidney, the mechanisms involved in its induction, and the IL-17A–mediated effector functions that promote renal tissue injury are incompletely understood. Here, using a murine model of crescentic GN, we found that CD4+ T cells, γδ T cells, and a population of CD3+CD4−CD8−γδT cell receptor−NK1.1− T cells all produce IL-17A in the kidney. A time course analysis identified γδ T cells as a major source of IL-17A in the early phase of disease, before the first CD4+ Th17 cells arrived. The production of IL-17A by renal γδ T cells depended on IL-23p19 signaling and retinoic acid–related orphan receptor-γt but not on IL-1β or IL-6. In addition, depletion of dendritic cells, which produce IL-23 in the kidney, reduced IL-17A production by renal γδ T cells. Furthermore, the lack of IL-17A production in γδ T cells, as well as the absence of all γδ T cells, reduced neutrophil recruitment into the kidney and ameliorated renal injury. Taken together, these data suggest that γδ T cells produce IL-17A in the kidney, induced by IL-23, promoting neutrophil recruitment, and contributing to the immunopathogenesis of crescentic GN.

GN as a disease category is one of the leading causes of progressive renal failure leading to ESRD.1 Among the different types of GN, crescentic GN is the most aggressive form and is associated with a poor prognosis. Entities such as ANCA-associated GN, anti–glomerular basement membrane nephritis, and immune complex–mediated GN (e.g., lupus nephritis) commonly present as crescentic GN.2

Recent studies have highlighted the pivotal role of the Th17 immune response in murine and human crescentic GN. This includes the identification and characterization of IL-17A–producing CD4+ T cells in nephritic kidneys of mice and humans, as well as evidence for the contribution of IL-17A and the IL-23/Th17 axis to renal tissue injury in GN.3–7 These pioneer studies focused on the function of “classic” CD4+ Th17 cells. However, recent studies showed that cells other than CD4+ T cells have the capability to produce IL-17A, such as γδ T cells,8–11 invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cells,12 lymphoid tissue inducer cells,13 and potentially neutrophils.14 These IL-17A+ innate-like immune cells might reside in the target organ, where they incite a rapid immune response upon activation even before the first CD4+ T cells see their cognate antigens in the secondary lymphoid organs and differentiate into Th17 effector cells. To our knowledge, the role of IL-17A production by non-CD4+ T cells in renal disease has not been addressed before.

The aim of the present study was to examine the contribution of different IL-17A–producing cell types to the nephritogenic immune response in crescentic GN. We therefore induced the T cell–dependent model of nephrotoxic nephritis to (1) define the time-dependent IL-17A expression profile of renal leukocyte subsets, (2) identify the mechanisms by which IL-17A expression is induced in these cells, and (3) determine the significance of specific IL-17A–producing cell subsets for the clinical outcome of experimental GN.

Results

T Cells Are the Main Producers of IL-17A in the Kidney

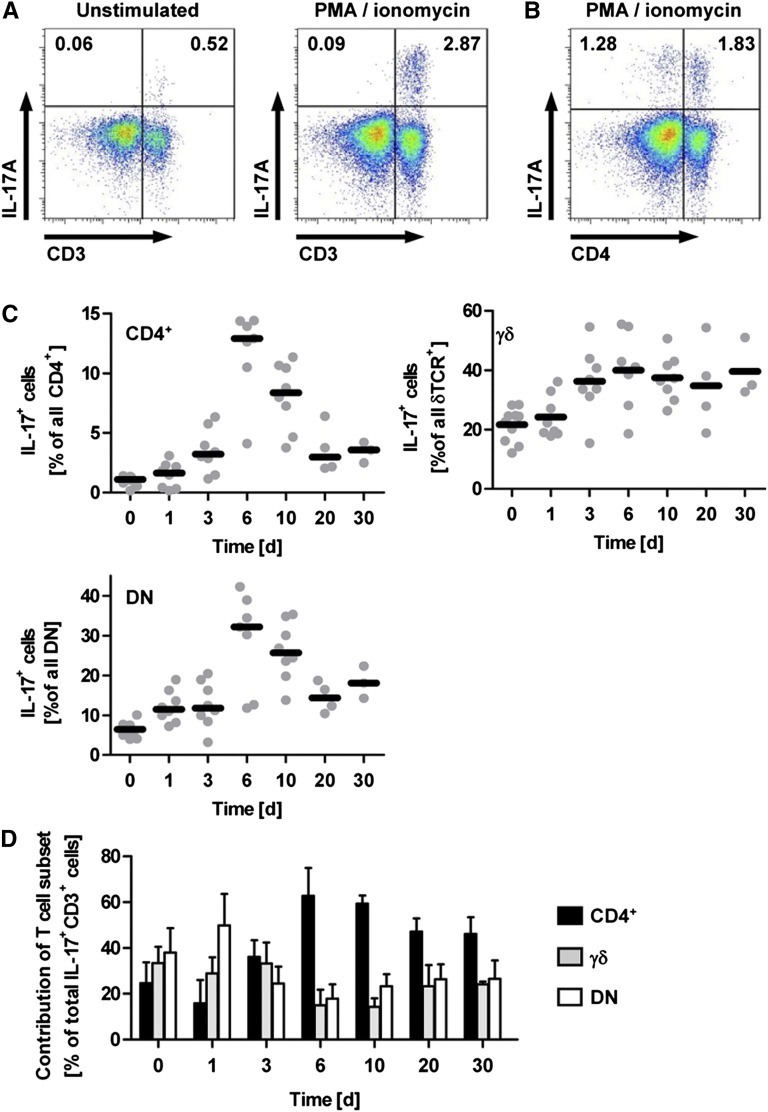

To investigate which cell types contribute to the production of IL-17A in the inflamed kidney, we isolated renal leukocytes from mice with nephrotoxic nephritis (NTN) at day 10 to perform intracellular cytokine staining and flow cytometric analysis after restimulation with PMA and ionomycin (Figure 1A). The restimulation resulted in robust IL-17A production by leukocytes isolated from inflamed kidneys, which was almost exclusively allocated to T cells by staining for the pan T cell marker CD3 (Figure 1A). It was remarkable, however, that CD4+ Th17 cells accounted for only about 60% of the IL-17A+ cells at day 10 of nephritis (Figure 1, B and D). Multicolor flow cytometric analysis enabled us to clearly identify intrarenal CD4+, CD8+, δT cell receptor (TCR)+, and NK1.1+ cells within the CD3+ population (Supplemental Figure 1), as well as a CD3+ population that was negative for all the T cell subset markers (referred to as the double-negative population) and accounted for 10%–15% all T cells.

Figure 1.

Time course of IL-17A production in experimental GN. (A and B) Flow cytometric analysis of renal leukocytes isolated from nephritic mice at day 10 after induction of NTN. For restimulation, cells were cultured with PMA/ionomycin for 4.5 hours before intracellular staining for IL-17A. Plots are gated for live CD45+ lymphocytes. Numbers indicate events in the quadrants in percentage of all gated events. (C) Quantification of the percentage of IL-17A+ cells in the respective T cell subset during the time course of the nephritis (n=7–10 per group for days 0–10 and n=3–4 per group for days 20 and 30). (D) Relative contribution of the IL-17A–producing T cell subsets (in percentages) to total IL-17A+CD3+ cells (100%) after restimulation with PMA/ionomycin at the given time points after induction of NTN. DN, double negative. Bars represent means ± SEM.

Contribution of T Cell Subsets to IL-17A Production in the Time Course of NTN

The flow cytometric analysis of renal T cell subsets revealed that even in naive mice, a considerable percentage of γδ T cells and double-negative T cells are able to produce IL-17A in response to stimulation with PMA and ionomycin, whereas only a small percentage of CD4+ T cells are IL-17A positive in naive mice (day 0; Figure 1C and Supplemental Figure 1). Next, we performed a time kinetic analysis of renal IL-17A+ T cell subsets after NTN induction (day 1–day 30). As in naive mice, IL-17A production was observed in the CD4+, δTCR+, and double-negative subsets throughout the time course of the nephritis (Figure 1C and Supplemental Figure 1), whereas NK1.1+ and CD8+ T cells remained IL-17A negative. As expected, the percentage of IL-17A+CD4+ Th17 cells was increased in the later phase from day 6 on. The IL-17A production by γδ T cells and double-negative T cells preceded the Th17 response with a moderate increase in double-negative T cells as early as day 1 (from approximately 6% to approximately 12% IL-17A+ double-negative T cells) and a pronounced increase in IL-17A+ γδ T cells at day 3 after induction of the nephritis (from approximately 20% to approximately 40% IL-17A+ γδ T cells) (Figure 1C). Furthermore, we noted an increased relative contribution of these “innate-like” T cells to the CD3+ infiltrate in this early phase of the immune response (Supplemental Figure 2), whereas the relative abundance of CD4+ T cells was increased only from day 10 onward. Analysis of the contribution of different T cell subsets (in percentages) to total IL-17A+CD3+ cells (100%) revealed that up to day 3 of nephrotoxic nephritis, γδ T cells and double-negative T cells are the main source of IL-17A in the kidney, whereas from day 6 on the CD4+ Th17 response predominates (Figure 1D).

IL-17A Is Produced by a Distinct Subset of γδ T Cells in the Kidney

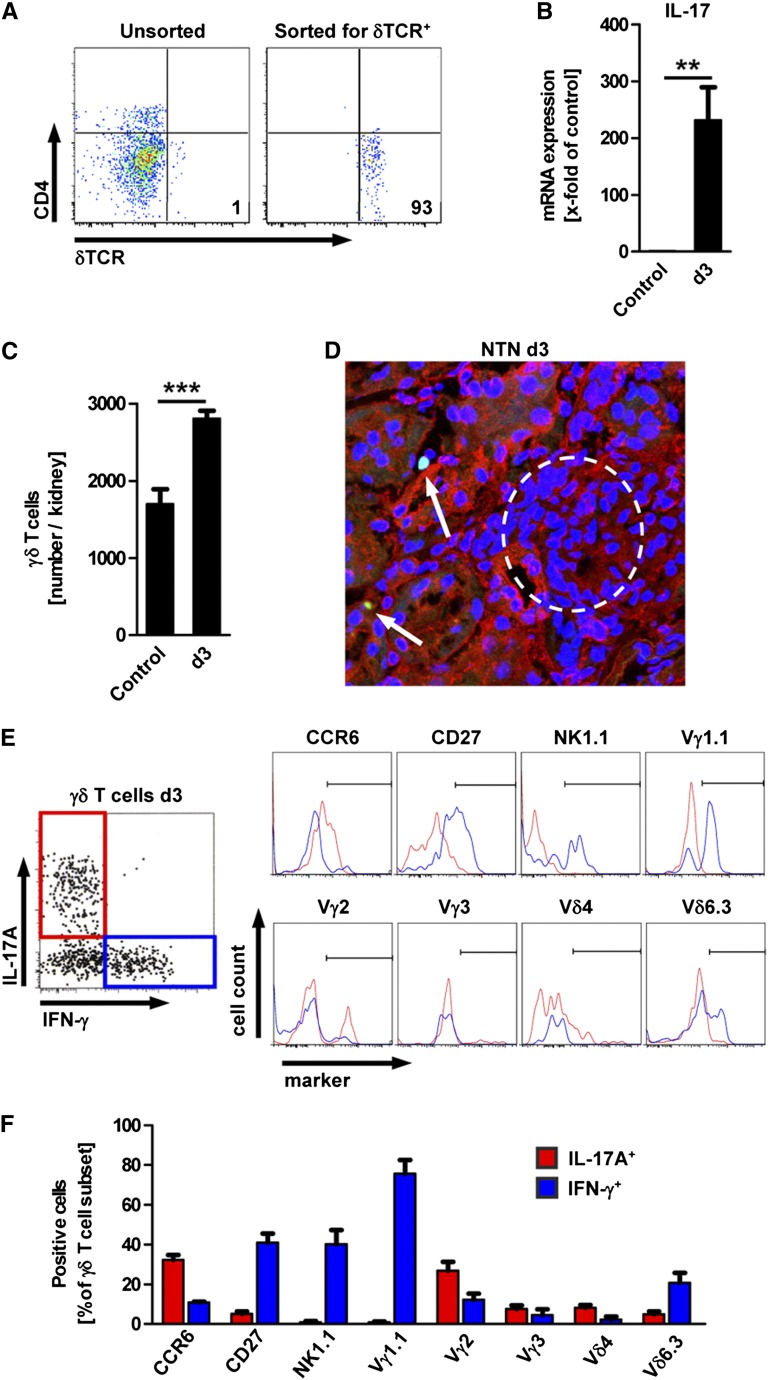

To confirm the flow cytometry data obtained after in vitro restimulation and intracellular staining for IL-17A, we FACS-sorted renal γδ T cells ex vivo from naive and nephritic mice and analyzed IL-17A mRNA expression in the sorted populations by quantitative RT-PCR (Figure 2, A and B). Renal γδ T cells isolated from nephritic mice at day 3 showed highly increased expression of IL-17A mRNA compared with naive controls (231-fold relative to control) (Figure 2B). Quantification of the absolute number of renal γδ T cells (by FACS analysis) revealed that these cells already reside in the kidney under control conditions and increase significantly at day 3 of the nephritis (Figure 2C). To locate the renal γδ T cells within the kidney, we took advantage of γδ TCR-H2b-enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) mice that express GFP in all cells that bear the γδ TCR.15 Using these mice, we could demonstrate the presence of γδ T cells in the tubulointerstitial infiltrates at day 3 after induction of NTN (Figure 2D). Further characterization of renal γδ T cells by FACS analysis revealed that IL-17A+ renal γδ T cells are a specific subset of γδ T cells that are distinct from IFN-γ–producing γδ T cells (Figure 2E). IL-17A+ γδ T cells showed higher expression of the surface marker CCR6 and the TCR chain Vγ2 (also known as Vγ4 according to the designation of Heilig and Tonegawa16), whereas the IFN-γ+ subsets were characterized by expression of CD27 and NK1.1, as well as the TCR chains Vγ1.1 and Vδ6.3 (Figure 2, E and F). The subset of double-negative T cells in the kidney contained a population of tetramer-positive (α-GalCer–specific) iNKT cells, but these cells were largely IL-17A negative. Furthermore, we observed that IL-17A+ DN T cells were distinct from IFN-γ+ double-negative T cells (Supplemental Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Characterization of IL-17+ γδ T cells in the kidney. (A) Flow cytometric assessment of the percentage of δTCR+ cells in renal leukocytes before and after FACS sorting for CD45+CD3+δTCR+ cells. Plots are gated on live CD45+ events. Numbers indicate events in the quadrant in percentage of all gated events. (B) IL-17A mRNA expression in renal γδ T cells sorted from naive mice (control) and at day 3 of the nephritis (d3) as shown in part A (n=5 per group). (C) Flow cytometric quantification of γδ T cells in the kidney of the respective groups (n=5 per group). (D) Immunofluorescence image of renal tissue section from γδTCR-H2b-eGFP mice 3 days after induction of NTN (green, γδTCR; blue, Topro III; red, wheat germ agglutinin; original magnification, ×400). (E) Flow cytometric analysis gated for renal γδ T cells after intracellular cytokine staining for IL-17A and IFN-γ 3 days after induction of NTN. The histograms show the expression of cell surface markers for IL-17A+ (red) and IFN-γ+ (blue) γδ T cells. (F) Frequency of surface marker expression in IL-17A+ or IFN-γ+ γδ T cells. Gating was performed as shown in part E (n≥3 per marker). Bars represent means ± SEM. **P<0.01; ***P<0.001.

Early IL-17A Production by Renal γδ T Cells Is Regulated by IL-23 and Retinoic Acid–Related Orphan Receptor-γt but Is Independent of IL-1β and IL-6

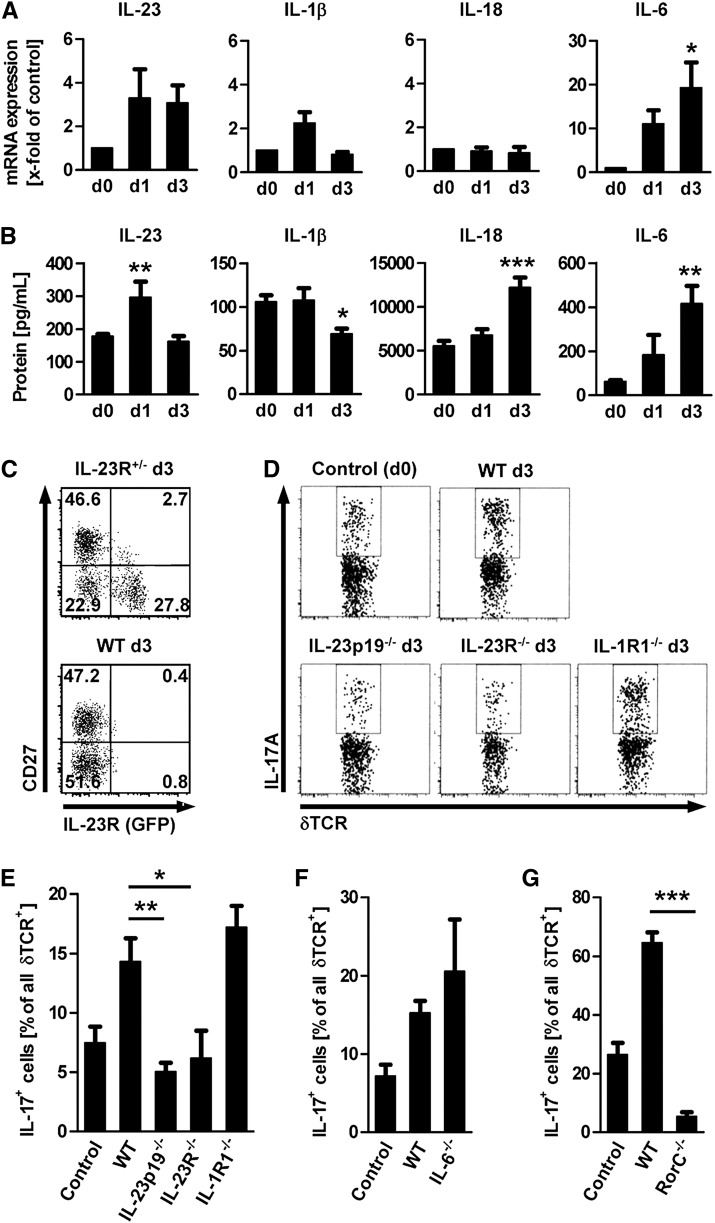

Next, we intended to investigate the mechanism by which early production of IL-17A by the “innate-like” T cell populations is induced in vivo. In a first step, we analyzed total renal cortex homogenates of mice with early NTN for mRNA and protein expression of the IL-17A–inducing cytokines IL-23p19, IL-1β, IL-18, and IL-6 (Figure 3, A and B). In line with a role for rapid induction of IL-17A production by local γδ T cells and double-negative T cells, we observed an upregulation of IL-23 protein as early as 24 hours after induction of NTN. IL-1β levels were generally lower, and IL-18 and IL-6 were not significantly upregulated on mRNA and protein level before day 3.

Figure 3.

Early IL-17A production by γδ T cells in the kidney is regulated by IL-23. (A and B) Time course of mRNA and protein expression of IL-23p19, IL-1β, IL-18, and IL-6 in the renal cortex (n=5–11 per time point). Bars represent means ± SEM (*P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001, all versus day 0). (C) Flow cytometric analysis of renal leukocytes isolated at day 3 of NTN from a heterozygous IL-23R GFP knock-in mouse and a wild-type (WT) mouse. Plots are gated on γδ T cells. (D and E) Flow cytometry plots and quantification of IL-17A+ γδ T cells in percentage of all renal γδ T cells isolated from wild-type, IL-23p19−/−, IL-23R−/−, and IL-1R1−/− mice 3 days after induction of NTN (n=3–7 per group). The percentages of IL-17A+ cells of all renal γδ T cells isolated from IL-6−/− (F) and RORγt–deficient mice (RorC−/−) (G) mice at day 3 after induction of NTN were quantified in separate experimental sets (n=3–5 per group). Bars represent means ± SEM. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001.

Next, we analyzed renal γδ T cells for the expression of the IL-23 receptor (IL-23R) by using heterozygous IL-23R GFP knock-in mice (Figure 3C).17 Co-staining with the surface marker CD27 that is preferentially expressed on IFN-γ+ γδ T cells (Figure 2, A and B) showed that the IL-23R-GFP signal is restricted to the CD27− subset, which contains most of the IL-17A–producing renal γδ T cells. To functionally address the role of the different cytokine pathways that may lead to IL-17A induction in vivo, we induced NTN in IL-23p19−/−, IL-23R−/−, IL-1R1−/−, and IL-6−/− mice and compared the IL-17A production by renal γδ T cells in the various knockout strains with that in nephritic wild-type mice at day 3 (Figure 3, D–F). The robust increase in the percentage of IL-17A+ γδ T cells that was observed in nephritic wild-type mice was completely abolished in IL-23p19– and IL-23R–deficient mice, whereas IL-1R1−/− and IL-6−/− mice had a similar percentage of IL-17A+ γδ T cells at day 3 of NTN. Furthermore, by using retinoic acid–related orphan receptor (ROR)γt–deficient mice we confirmed that the transcription factor RORγt is crucial for the IL-17A production by γδ T cells in the kidney during the early phase of NTN (Figure 3G). Although induction in the double-negative T cell subset was less pronounced at day 3, the IL-17A production also clearly depended on IL-23 signaling and RORγt expression in this subset, but not on IL-1β (Supplemental Figure 4).

Kidney Dendritic Cells Produce IL-23 and Stimulate IL-17A Production in Renal γδ T Cells

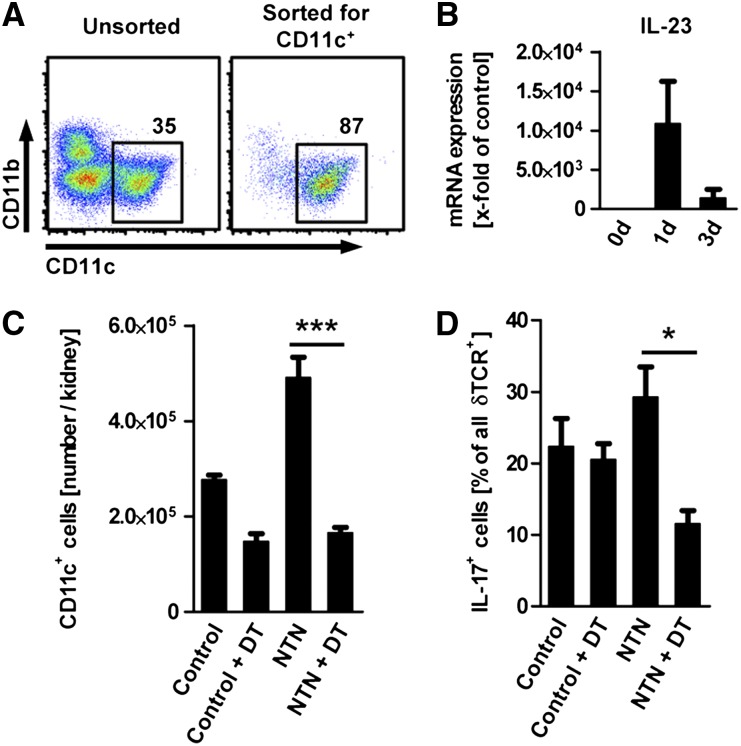

To test whether the rapid increase of IL-23 protein might be due to enhanced IL-23 production by renal dendritic cells, we sorted renal dendritic cells from NTN mice and controls according to their expression of CD11c to a purity of >85% (Figure 4A) and subjected them to quantitative RT-PCR. Renal dendritic cells showed a strong increase in IL-23 production as early as 24hours after the injection of the nephritogenic sheep serum (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Kidney dendritic cells stimulate IL-17A production by local γδ T cells. (A) Flow cytometric assessment of the percentage of CD11c+ dendritic cells in renal leukocytes before and after magnetic bead sorting for CD11c. Plots are gated on live CD45+ events. Numbers indicate events in the gate in percentage of all events shown. (B) mRNA expression of IL-23p19 in renal dendritic cells sorted as shown in part A (n=3–5 per group). (C) Number of renal CD11c+ dendritic cells in control CD11c-DTR mice (control) and in CD11c-DTR mice 3 days after induction of the nephritis (NTN). Dendritic cells were depleted as indicated by injection of diphtheria toxin (DT) 18 hours before the analysis at day 3 (n=3 per group). (D) Quantification of IL-17A+ γδ T cells in percentage of all renal γδ T cells isolated from CD11c-DTR mice with and without NTN or depletion of dendritic cells. Group numbers as in part C. Bars represent means ± SEM *P<0.05; ***P<0.001.

To verify the hypothesis that renal dendritic cells are necessary for increased IL-17A production by local γδ T cells, we used the CD11c-DTR mice, in which dendritic cells can be depleted by injection of diphtheria toxin. As shown previously,18 renal dendritic cells were effectively depleted in NTN and control mice by a single dose of diphtheria toxin (Figure 4C). Flow cytometric analysis of renal γδ T cells at day 3 of NTN showed a significant reduction in the percentage of IL-17A+ cells after dendritic cell depletion, suggesting that renal dendritic cells are essential for induction or maintenance of IL-17A production by local γδ T cells (Figure 4D).

γδ T Cells Enhance Neutrophil Infiltration and Aggravate Tissue Damage in NTN

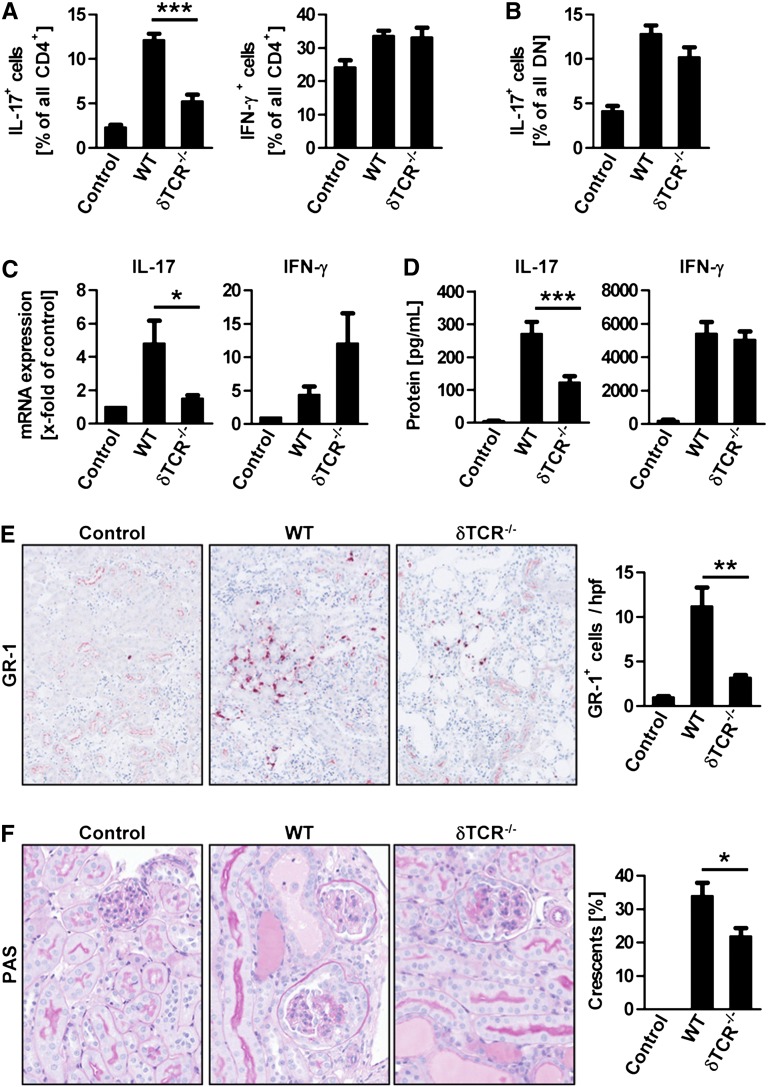

To investigate the function of γδ T cells in our model of NTN and provide insight in the underlying mechanisms, we induced NTN in δTCR−/− mice and analyzed them at day 6 when crescentic GN has developed. Flow cytometric analysis of IL-17A+ and IFN-γ+ CD4+ T cells from the kidney after restimulation with PMA and ionomycin showed a selective reduction of Th17 cells in absence of γδ T cells (Figure 5A). Remarkably, the IL-17A production by DN T cells, as well as the production of nephritogenic antibodies, was unimpaired in δTCR−/− mice (Figure 5B and Supplemental Figure 5). This selective reduction of renal IL-17A production after restimulation, which is mainly derived from CD4+ T cells at day 6 (see Figure 1D), was confirmed by reduced IL-17A mRNA levels in total renal cortex (Figure 5C). Furthermore, cultured splenocytes from δTCR−/− mice with NTN showed a reduced production of IL-17A, but not IFN-γ, suggesting a requirement of γδ T cells for the generation of the Th17 response in the secondary lymphoid organs (Figure 5D). Interestingly, the low basal levels of IL-17A production in kidneys and spleens of naive δTCR−/− mice were similar to those of wild-type controls (data not shown). Most important, the absence of γδ T cells resulted in impaired neutrophil and macrophage infiltration into the kidney of δTCR−/− mice (Figure 5E and Supplemental Figure 6) and reduced kidney injury, as measured by the percentage of glomeruli with crescentic lesions (Figure 5F). Moreover, the serum creatinine levels at day 6 were significantly reduced in nephritic δTCR−/− mice in comparison with the nephritic control group (Supplemental Figure 7).

Figure 5.

γδ T cells aggravate crescentic GN by stimulating the Th17 response. (A) Quantification of the percentage of IL-17A+ and IFN-γ+ cells in the renal CD4+ T cell subset isolated from controls (n=4), nephritic wild-type (WT, n=6), and nephritic δTCR−/− mice (n=7) 6 days after induction of NTN. For restimulation, cells were cultured with PMA/ionomycin for 4.5 hours before intracellular cytokine staining. (B) Percentage of IL-17A+ cells in the double-negative T cell subset. (C) Quantitative RT-PCR measurement of IL-17A and IFN-γ mRNA expression in the renal cortex. (D) ELISA measurement of IL-17A and IFN-γ protein concentrations from supernatants of splenocytes stimulated for 60 hours with sheep IgG. (E) Immunohistochemistry for the neutrophil marker GR-1 (original magnification, ×400) and quantification of GR-1+ cells from renal tissue sections. (F) Periodic acid-Schiff staining of renal tissue sections (original magnification, ×400) and quantification of the percentage of crescentic glomeruli. Group sizes for parts B to E are the same as in part A. Bars represent means ± SEM. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001.

IL-17A Production by γδ T Cells Contributes to Immune-Mediated Kidney Injury

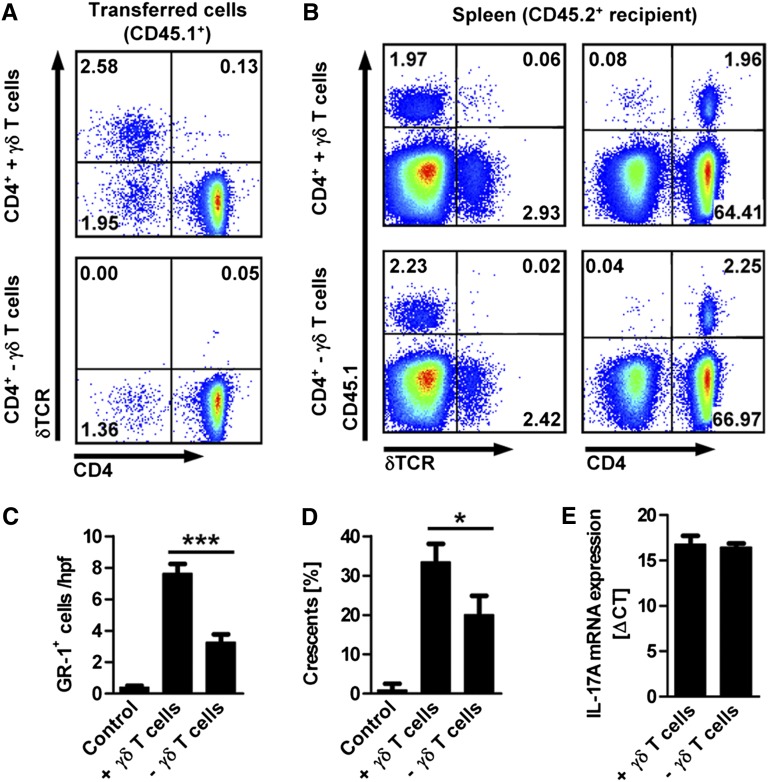

Having shown that γδ T cells, in general, have a pathogenic role in the NTN model and function as enhancers of the Th17 response, we next wanted to know whether IL-17A production by γδ T cells is required for this effect. We addressed this question by reconstituting IL-17A–deficient hosts with a combination of cells that were sorted from spleens of CD45.1+ IL-17A–competent donors by magnetic-bead activated cell sorting (MACS). In this experiment, mice that received a combination of CD4+ and double-negative T cells together with γδ T cells were compared with mice that received the combination of CD4+ and double-negative T cells depleted of γδ T cells (Figure 6A). The transferred γδ T cells and CD4+ cells could be identified in the spleens of the recipients by staining for the congenic marker CD45.1 (Figure 6B). Remarkably, the lack of IL-17A–competent γδ T cells in IL-17A−/− hosts was sufficient to significantly reduce neutrophil infiltration into the kidney and glomerular crescent formation at day 6 of NTN (Figure 6, C and D), underlining the important pathogenic role of γδ T cell–derived IL-17A in GN. In this experiment, however, the renal function measures did not significantly differ between the two nephritic groups (Supplemental Figure 8). Importantly, the CD4+ Th17 differentiation, which was reduced in δTCR−/− (see Figure 5), seemed unaffected by the absence of γδ T cell–derived IL-17A; we observed similar IL-17A mRNA expression levels in the transferred CD45.1+CD4+ T cells FACS-sorted from the spleens of both groups of recipients (Figure 6E).

Figure 6.

IL-17A production by γδ T cells contributes to immune-mediated kidney injury. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of the cell populations isolated by magnetic bead sorting from spleens of IL-17A–competent CD45.1+ donors. Congenic IL-17A–deficient CD45.2+ recipients received a combination of CD4+ T cells, double-negative T cells, and γδ T cells (upper panel) or a combination of CD4+ T cells and double-negative T cells without γδ T cells (lower panel). Transfer of 5–8×106 cells was performed 24 hours before induction of NTN in IL-17A−/− mice. (B) Flow cytometric analysis of splenocytes isolated from CD45.2+ IL-17A−/− recipients on day 6 after induction of the nephritis. Plots in parts A and B are gated on live cells and the numbers indicate events in the quadrants in percentage of all gated events. (C and D) Quantification of GR-1+ cells (neutrophils) and crescent formation in kidney sections of both groups of cell recipients after 6 day of NTN, as well as in naive IL-17A−/− mice (control) (n=4 per group). (E) Quantitative RT-PCR of IL-17A mRNA expression in transferred (CD45.1+) CD4+ T cells FACS-sorted from the spleen of both groups of cell recipients at day 6 after induction of the nephritis (n=3 per group). mRNA level is expressed as Δcross threshold value normalized to the 18s expression in the respective sample. Bars represent means ± SEM. *P<0.05; ***P<0.001.

Discussion

In this study, we provide a comprehensive in vivo analysis of IL-17A production by “conventional” and “nonconventional” T cell subsets in the kidney during the time course of a murine model of GN. We identify distinct subsets of γδ T cells and CD3+CD4−CD8−δTCR−NK1.1− double-negative T cells as important sources of IL-17A early in the disease. IL-17A from these cells is rapidly induced by IL-23 (which is produced in large amounts by local dendritic cells) and functions to recruit neutrophils that promote renal tissue injury.

In the recent years, γδ T cells have been increasingly recognized as an important source of IL-17A in several autoimmune diseases.8,11,19–21 Although a few reports convincingly demonstrate an important role of the IL-23/IL-17A axis for the pathogenesis of renal inflammation,3–5 it has been a matter of debate whether other cell types, apart from “classic” CD4+ Th17 cells, may contribute to IL-17A production in the kidney.22–24 We show here that “innate-like” T cells contribute significantly to the IL-17A production in the kidney during early NTN, whereas in the later phase from day 6 on CD4+ Th17 cells are the predominant source. Remarkably, we found that after restimulation with PMA and ionomycin, IL-17A production in naive and inflamed kidneys is restricted to T cells; this argues against other cell types, such as innate lymphoid cells25 and neutrophils,14 as important sources of IL-17A in murine crescentic GN. In line with reports from other peripheral tissues,8,10,11,19,20,26 renal IL-17A+ γδ T cells represent a distinct subset that is characterized by expression of CCR6 and the TCR chain Vγ2 (also known as Vγ4 according to the designation of Heilig and Tonegawa16). The quantification of renal γδ T cells revealed that these cells already reside in the naive murine kidney, where they might act as “sentinel” cells that can orchestrate an inflammatory response to pathogens and other environmental signals before CD4+ T cells are activated. In addition to IL-17A–producing renal γδ T cells, we characterize a previously unrecognized subset of double-negative T cells that upregulates IL-17A production as early as day 1 after induction of the disease and requires cytokine signals similar to the IL-17A+ γδ T cell population. IL-17A–producing “innate-like” double-negative T cell populations have been described in bacterial infections27–29 and might comprise a population of NK1.1− NKT cells with specificity different from that of α-GalCer. The function of this subset in autoimmunity is unclear and awaits further studies.

Recent studies demonstrated that in vitro culture with IL-23, together with the caspase-cleaved cytokines IL-1β or IL-18, can induce IL-17A production in γδ T cells independent of TCR activation.11,20,30 By using IL-23p19– and IL-23R–deficient mice, we establish a crucial in vivo role of IL-23 for the induction of IL-17A production by γδ T cells in our model of renal inflammation. In contrast to the published results,11,20,30 IL-17A production by renal γδ T cells did not depend on IL-1R1. However, because the IL-1–related cytokine IL-18 was expressed in the inflamed kidney, it is possible that IL-18 signaling compensated for the lack of IL-1R1 signaling in our setting.30

Mostly on the basis of in vitro experiments, the current concept presumes that IL-23, which induces IL-17A production in the peripheral tissue, is provided by local dendritic cells,11,20 but functional in vivo evidence for this concept from animal models is still missing. In the present study, we show that IL-17A production by renal γδ T cells is reduced after depletion of dendritic cells in CD11c-DTR mice. This indicates a direct functional link between dendritic cell–derived IL-23 and induction of IL-17A expression in γδ T cells. However, to finally prove this concept, in vivo studies with dendritic cell–specific IL-23p19 gene-deficient mice, which are currently not available, would be important.

The function of γδ T cells in experimental GN was first investigated by Rosenkranz et al. using δTCR gene-deficient mice.31 In line with our results, mice deficient in γδ T cells showed reduced neutrophil and macrophage infiltration into the kidney, developed less severe renal tissue injury, and showed less impairment of renal function compared with nephritic wild-type mice. In contrast, Wu et al. reported that the depletion of γδ T cells, using the anti-δTCR antibody UC7–13D5, exacerbates the course of adriamycin nephropathy, a murine model of human FSGS.32 However, treatment with the UC7–13D5 antibody does not deplete γδ T cells in vivo but rather leads to TCR internalization and thereby generates “invisible,” but activated, γδ T cells.33 This might be a possible explanation for the controversial findings described above. However, the mechanisms used by renal γδ T cells to exert their pathogenic effects have not been addressed in detail by the studies mentioned above.

In the present study, we demonstrate that the absence of all γδ T cells results in a reduced Th17 response in the spleen and kidney, whereas Th1 response and humoral immunity were unimpaired. Furthermore, we observed a significant reduction of neutrophil recruitment and renal tissue damage in nephritic δTCR knock-out mice compared with their wild-type counterpart. These results are in line with previous studies in other animal models of autoimmunity that described impaired generation of CD4+ Th17 cells11,34,35 and/or reduced infiltration of neutrophils in the absence of γδ T cells.20 To address the question of whether the ameliorated phenotype of δTCR-deficient mice is a secondary effect due to the reduced CD4+ Th17 response, we performed cell transfer experiments, demonstrating that the reduction of neutrophil recruitment and tissue damage is at least partially dependent on γδ T cell–derived IL-17A. A published study in the model of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis furthermore suggests that IL-17A itself is able to enhance the CD4+ Th17 cell differentiation.11 In contrast to these results, our transfer experiment shows that the generation of CD4+ Th17 cells in the spleen is independent of IL-17A–competent γδ T cells, suggesting that γδ T cells enhance the CD4+ Th17 response in experimental GN by effector molecules different from IL-17A.

With respect to the pathogenesis of renal disease in humans, the function of γδ T cells is not well defined. First evidence for a potential role of γδ T cells in the kidney derived from analyses of renal biopsy specimens from patients with IgA nephropathy, which showed a significant increase in CD3+ γδ T cells as assessed by immunohistochemistry. Most important, the abundance of γδ T cells was associated with a progressive course of IgA nephropathy,36 underscoring the potential importance of γδ T cells in human renal autoimmune diseases.

In conclusion, our study identifies a new pathogenic (in vivo) mechanism, involving dendritic cells, IL-23p19, IL-23 receptor, γδ T cells, and IL-17A, that significantly contributes to renal tissue injury in experimental GN. These data indicate that IL-17A–producing γδ T cells play a pivotal role in the early inflammatory response of the kidney. Targeting of this pathway might be therapeutically exploited in the future.

Concise Methods

Animals

All mice in this study were on C57BL/6 background. IL-23 receptor–deficient mice and γδTCR-H2b-eGFP mice have been described elsewhere.15,17 IL-17A–deficient (IL-17A−/−) mice were provided by Y. Iwakura (Institute of Medical Science, University of Tokyo, Japan). RORγt–deficient mice were a kind gift of D. Littman (New York University School of Medicine, New York).37 IL1R1−/−, δTCR−/−, and CD45.1 congenic mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine). IL-6−/− mice were a gift of S. Rose-John (Institute of Biochemistry, Christian-Albrechts-Universität, Kiel, Germany). IL-23p19−/− mice were provided by N. Ghilardi (Genentech, San Francisco, CA). CD11c-DTR mice were from S. Jung (Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel).

Induction of NTN and Functional Studies

NTN was induced in 8- to 10-week-old male mice by intraperitoneal injection of 0.5 ml of nephrotoxic sheep serum as previously described.4 For dendritic cell depletion, CD11c-DTR mice were injected with 8 ng/g body weight diphtheria toxin (Sigma-Aldrich). Urinary albumin content was determined by standard ELISA (mice albumin kit; Bethyl Laboratories, Montgomery, TX). Urinary and serum creatinine levels were measured by using the Dimension Vista 1500 Intelligent Lab System (Siemens, Munich, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Real-Time RT-PCR analysis

Total RNA of the renal cortex was prepared according to standard laboratory methods. Real-time PCR was performed in a Step One Plus Real-time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). All samples were run in duplicate and normalized to 18S rRNA to account for small variabilities in RNA and cDNA content.

Morphologic Examinations

Light microscopy and immunohistochemistry were performed by routine procedures. Crescent formation was assessed in 30 glomeruli per mouse in a blinded fashion in periodic acid-Schiff–stained paraffin sections. Paraffin-embedded sections (2 µm) were stained with antibodies directed against the neutrophil marker GR-1 (Ly6 G/C) (NIMP-R14, Hycult Biotech, the Netherlands), the macrophage/dendritic cell marker F4/80 (BM8; BMA Biomedicals, Augst, Switzerland), or the glomerular monocyte marker MAC-2 (M3/38; Cedarlane, Burlington, Ontario, Canada) and developed with a polymer-based secondary antibody alkaline phosphatase kit (POLAP, Zytomed, Berlin, Germany).

Detection of γδ T Cells in Cryosections

Kidneys of nephritic γδTCR-H2b-eGFP mice were preserved for cryosectioning in Tissue Tek (Sakurea Finetek, the Netherlands). Tissue architecture was visualized using Texas red–conjugated wheat germ agglutinin (vector) 1:400 for 30 minutes. Nuclei were visualized using TO-PRO-3 (Life Technologies GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany) 1:2000 for 5 minutes at room temperature. γδΤ-cell localization within kidneys was evaluated by confocal microscopy with a LSM 510 meta microscope (Zeiss) using the LSM software.

Leukocyte Isolation from Kidney and Spleen

Previously described methods for leukocyte isolation from murine kidneys were used.38 In brief, kidneys were finely minced and digested for 40 minutes with collagenase D and deoxyribonuclease (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FCS (Invitrogen). Tubular fragments from digested kidneys were removed by filtration and sedimentation; subsequently erythrocytes were lysed with ammonium chloride.

Splenocyte Cultures

A total of 4×106 cells/ml were incubated for 60 hours in the presence of sheep IgG. Supernatants were collected and IL-17A and IFN-γ were measured by ELISA according to the manufacturer’s instructions (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

Flow Cytometry

For FACS analysis, the following fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies were used: CD45 (30-F11), CD45.1 (104), CD3 (17A2), CD4 (GK1.5), CD8 (53–6.7), γδTCR (GL3), NK1.1 (PK136), CCR6 (140706), CD27 (LG.3A10), Vγ1.1 (2.11), Vγ2 (UC3–10A6), Vγ3 (536), Vδ4 (GL2), Vδ6.3 (8F4H7H7), CD11b (M1/70), and CD11c (HL3) or α-GalCer loaded CD1d-Tetramer (L363) (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ; Biolegend, San Diego, CA; eBioscience, San Diego, CA). Staining of intracellular IL-17A (TC11–18H10.1) and IFN-γ (XMG1.2) was performed as recently described. In brief, cells were activated by incubation at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 4 hours with PMA (50 ng/ml; Sigma) and ionomycin (1 µg/ml; Calbiochem-Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) in X-VIVO medium (Lonza AG, Walkersville, MD). After 30 minutes of incubation, Brefeldin A (10 µg/ml; Sigma) was added. Dead cell staining was performed (LIVE/DEAD Fixable Read Dead Stain Kit, Invitrogen). Samples were acquired on a Becton Dickinson LSRII System using the Diva software. Data analysis was performed with the FlowJo software (Tree Star Inc., Ashland, OR).

Cell Sorting

FACS sorting was performed on a Becton Dickinson Aria III System. In case of MACS sorting, cells were labeled according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Miltenyi, Bergisch-Gladbach, Germany). The sorting result was verified by flow cytometry.

Cell Transfer Experiments

MACS sorting of CD4+ cells (mouse CD4+ cell isolation kit II, Miltenyi) was performed. In addition, γδ T cells were depleted using biotin- or FITC-labeled anti–γδ-TCR antibody (clone GL3, BD Biosciences) and a corresponding bead-coupled secondary antibody (Miltenyi). A total of 5–8×106 cells isolated from the spleens of naive congenic CD45.1 mice were transferred into recipient CD45.2 IL-17A−/− by intravenous injection 24 hours before the induction of nephritis.

Statistical Analyses

Differences between two individual experimental groups (of normally distributed values) were compared by a two-tailed t test. In the case of multiple comparisons, one-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni post-test for multiple comparisons was used. Experiments that did not yield enough independent data for statistical analysis because of the experimental setup were repeated at least three times.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

We thank Anett Peters for her excellent technical help. We further thank Joachim Velden for making histology images.

This work was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (KFO 228: PA 754/7-1 to UP and JET, KU1063/7-1 to C. Kurts) and KO2964/3-1 to TK.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2012010040/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Chadban SJ, Atkins RC: Glomerulonephritis. Lancet 365: 1797–1806, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tarzi RM, Cook HT, Pusey CD: Crescentic glomerulonephritis: New aspects of pathogenesis. Semin Nephrol 31: 361–368, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dong X, Bachman LA, Miller MN, Nath KA, Griffin MD: Dendritic cells facilitate accumulation of IL-17 T cells in the kidney following acute renal obstruction. Kidney Int 74: 1294–1309, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paust HJ, Turner JE, Steinmetz OM, Peters A, Heymann F, Hölscher C, Wolf G, Kurts C, Mittrücker HW, Stahl RA, Panzer U: The IL-23/Th17 axis contributes to renal injury in experimental glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 969–979, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ooi JD, Phoon RK, Holdsworth SR, Kitching AR: IL-23, not IL-12, directs autoimmunity to the Goodpasture antigen. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 980–989, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Summers SA, Steinmetz OM, Li M, Kausman JY, Semple T, Edgtton KL, Borza DB, Braley H, Holdsworth SR, Kitching AR: Th1 and Th17 cells induce proliferative glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 2518–2524, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tulone C, Giorgini A, Freeley S, Coughlan A, Robson MG: Transferred antigen-specific T(H)17 but not T(H)1 cells induce crescentic glomerulonephritis in mice. Am J Pathol 179: 2683–2690, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roark CL, French JD, Taylor MA, Bendele AM, Born WK, O’Brien RL: Exacerbation of collagen-induced arthritis by oligoclonal, IL-17-producing gamma delta T cells. J Immunol 179: 5576–5583, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roark CL, Simonian PL, Fontenot AP, Born WK, O’Brien RL: gammadelta T cells: An important source of IL-17. Curr Opin Immunol 20: 353–357, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin B, Hirota K, Cua DJ, Stockinger B, Veldhoen M: Interleukin-17-producing gammadelta T cells selectively expand in response to pathogen products and environmental signals. Immunity 31: 321–330, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sutton CE, Lalor SJ, Sweeney CM, Brereton CF, Lavelle EC, Mills KH: Interleukin-1 and IL-23 induce innate IL-17 production from gammadelta T cells, amplifying Th17 responses and autoimmunity. Immunity 31: 331–341, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Michel ML, Mendes-da-Cruz D, Keller AC, Lochner M, Schneider E, Dy M, Eberl G, Leite-de-Moraes MC: Critical role of ROR-γt in a new thymic pathway leading to IL-17-producing invariant NKT cell differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105: 19845–19850, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takatori H, Kanno Y, Watford WT, Tato CM, Weiss G, Ivanov II, Littman DR, O’Shea JJ: Lymphoid tissue inducer-like cells are an innate source of IL-17 and IL-22. J Exp Med 206: 35–41, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li L, Huang L, Vergis AL, Ye H, Bajwa A, Narayan V, Strieter RM, Rosin DL, Okusa MD: IL-17 produced by neutrophils regulates IFN-gamma-mediated neutrophil migration in mouse kidney ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Clin Invest 120: 331–342, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prinz I, Sansoni A, Kissenpfennig A, Ardouin L, Malissen M, Malissen B: Visualization of the earliest steps of gammadelta T cell development in the adult thymus. Nat Immunol 7: 995–1003, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heilig JS, Tonegawa S: Diversity of murine gamma genes and expression in fetal and adult T lymphocytes. Nature 322: 836–840, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Awasthi A, Riol-Blanco L, Jäger A, Korn T, Pot C, Galileos G, Bettelli E, Kuchroo VK, Oukka M: Cutting edge: IL-23 receptor gfp reporter mice reveal distinct populations of IL-17-producing cells. J Immunol 182: 5904–5908, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hochheiser K, Engel DR, Hammerich L, Heymann F, Knolle PA, Panzer U, Kurts C: Kidney Dendritic Cells Become Pathogenic during Crescentic Glomerulonephritis with Proteinuria. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 306–316, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ito Y, Usui T, Kobayashi S, Iguchi-Hashimoto M, Ito H, Yoshitomi H, Nakamura T, Shimizu M, Kawabata D, Yukawa N, Hashimoto M, Sakaguchi N, Sakaguchi S, Yoshifuji H, Nojima T, Ohmura K, Fujii T, Mimori T: Gamma/delta T cells are the predominant source of interleukin-17 in affected joints in collagen-induced arthritis, but not in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 60: 2294–2303, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cai Y, Shen X, Ding C, Qi C, Li K, Li X, Jala VR, Zhang HG, Wang T, Zheng J, Yan J: Pivotal role of dermal IL-17-producing γδ T cells in skin inflammation. Immunity 35: 596–610, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petermann F, Rothhammer V, Claussen MC, Haas JD, Blanco LR, Heink S, Prinz I, Hemmer B, Kuchroo VK, Oukka M, Korn T: γδ T cells enhance autoimmunity by restraining regulatory T cell responses via an interleukin-23-dependent mechanism. Immunity 33: 351–363, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Free ME, Falk RJ: IL-17A in experimental glomerulonephritis: Where does it come from? J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 885–886, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kitching AR, Holdsworth SR: The emergence of TH17 cells as effectors of renal injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 235–238, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Turner JE, Paust HJ, Steinmetz OM, Panzer U: The Th17 immune response in renal inflammation. Kidney Int 77: 1070–1075, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spits H, Di Santo JP: The expanding family of innate lymphoid cells: Regulators and effectors of immunity and tissue remodeling. Nat Immunol 12: 21–27, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bonneville M, O’Brien RL, Born WK: Gammadelta T cell effector functions: A blend of innate programming and acquired plasticity. Nat Rev Immunol 10: 467–478, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cowley SC, Meierovics AI, Frelinger JA, Iwakura Y, Elkins KL: Lung CD4-CD8- double-negative T cells are prominent producers of IL-17A and IFN-gamma during primary respiratory murine infection with Francisella tularensis live vaccine strain. J Immunol 184: 5791–5801, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Doisne JM, Soulard V, Bécourt C, Amniai L, Henrot P, Havenar-Daughton C, Blanchet C, Zitvogel L, Ryffel B, Cavaillon JM, Marie JC, Couillin I, Benlagha K: Cutting edge: crucial role of IL-1 and IL-23 in the innate IL-17 response of peripheral lymph node NK1.1- invariant NKT cells to bacteria. J Immunol 186: 662–666, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Riol-Blanco L, Lazarevic V, Awasthi A, Mitsdoerffer M, Wilson BS, Croxford A, Waisman A, Kuchroo VK, Glimcher LH, Oukka M: IL-23 receptor regulates unconventional IL-17-producing T cells that control bacterial infections. J Immunol 184: 1710–1720, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lalor SJ, Dungan LS, Sutton CE, Basdeo SA, Fletcher JM, Mills KH: Caspase-1-processed cytokines IL-1beta and IL-18 promote IL-17 production by gammadelta and CD4 T cells that mediate autoimmunity. J Immunol 186: 5738–5748, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosenkranz AR, Knight S, Sethi S, Alexander SI, Cotran RS, Mayadas TN: Regulatory interactions of alphabeta and gammadelta T cells in glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int 58: 1055–1066, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu H, Wang YM, Wang Y, Hu M, Zhang GY, Knight JF, Harris DC, Alexander SI: Depletion of gammadelta T cells exacerbates murine adriamycin nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 1180–1189, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koenecke C, Chennupati V, Schmitz S, Malissen B, Förster R, Prinz I: In vivo application of mAb directed against the gammadelta TCR does not deplete but generates “invisible” gammadelta T cells. Eur J Immunol 39: 372–379, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cui Y, Shao H, Lan C, Nian H, O’Brien RL, Born WK, Kaplan HJ, Sun D: Major role of gamma delta T cells in the generation of IL-17+ uveitogenic T cells. J Immunol 183: 560–567, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Do JS, Visperas A, Dong C, Baldwin WM, 3rd, Min B: Cutting edge: Generation of colitogenic Th17 CD4 T cells is enhanced by IL-17+ γδ T cells. J Immunol 186: 4546–4550, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Falk MC, Ng G, Zhang GY, Fanning GC, Roy LP, Bannister KM, Thomas AC, Clarkson AR, Woodroffe AJ, Knight JF: Infiltration of the kidney by alpha beta and gamma delta T cells: Effect on progression in IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int 47: 177–185, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eberl G, Marmon S, Sunshine MJ, Rennert PD, Choi Y, Littman DR: An essential function for the nuclear receptor RORgamma(t) in the generation of fetal lymphoid tissue inducer cells. Nat Immunol 5: 64–73, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Turner JE, Paust HJ, Bennstein SB, Bramke P, Krebs C, Steinmetz OM, Velden J, Haag F, Stahl RA, Panzer U: Protective role for CCR5 in murine lupus nephritis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 302: F1503–F1515, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]